-

The Standard(s) for the Foundation Of KnowledgeOne should not understand this compulsion to construct concepts, species, forms, purposes, laws ('a world of identical cases') as if they enabled us to fix the real world; but as a compulsion to arrange a world for ourselves in which our existence is made possible:we thereby create a world which is calculable, simplified, comprehensible, etc., for us.

Our cognitive apparatus is not organized for 'knowledge.'

[T]he aberration of philosophy comes from this:instead of seeing logic and the categories of reason as means to the adaptation of the world to ends of utility (that is, "in principle," for a useful falsification) men believe to possess in them the criterion of truth or reality.

~Nietzsche

I agree with Habermas, extending this reasoning, that in the context of this "transcendentally-logically conceived pragmatism" there are a wide array of "knowledge-constitutive and knowledge-legitimating interests" beyond the merely logical and technical. -

Tyrannical Hijacking of Marx’s IdeologyAs proven by history that all communist systems have been enforced by dictators I see no further adaptation or advancement of his theory that could save it.

Nuanced forms of socialism could be one way, the other is to accept capitalism as the best we have although not perfect.

Back to the title of the thread and main point there could not be a form of government that embodies Marx’s system without resorting to some form of liberty denying authoritarianism. — Deus

The tone of this seems to fall in the category of demonizing communism typical of many advocates of capitalism. Has the spirit of Marx's communism been corrupted? Sure. Just like every other ideal that humanity attempts to implement. I am not a communist, but I do believe that we can achieve a much higher level of social justice. But that spirit of social justice isn't a product of a particular economic system or form of government. Rather, the success or failure of those is a function of the spirit of social justice. -

Where Do The Profits Go?The simplest way to change the undemocratic, plutocratic system is to take their property away from them without compensation.

— Bitter Crank

Why is this simpler than having workers have a few board seats? I think that’s at least less extreme. — Xtrix

So this is just a special case of the failure of democracy in general. Ideally, a democratic society would naturally evolve to minimize the plutocratic influence. Instead, what we see everywhere and without exception is the ever-increasing corruption of democratic ideals through the infiltration of plutocratic influences. The gap between the rich and the poor has been steadily increasing as long as it has been measured. So clearly technological knowledge is socially and morally meaningless (or worse, socially and morally damaging). Handing out a few board seats is only going to create a few more martyrs. Or a few new plutocrats.

If we turn to those restrictions that only apply to certain classes of society, we encounter a state of things which is glaringly obvious and has always been recognized. It is to be expected that the neglected classes will grudge the favoured ones their privileges and that they will do everything in their to power to rid themselves of their own surplus of privation. Where this is not possible a lasting measure of discontent will obtain within this culture, and this may lead to dangerous outbreaks. But if a culture has not got beyond the stage in which the satisfaction of one group of its members necessarily involves the suppression of another, perhaps the majority---and this is the case in all modern cultures,---it is intelligible that these suppressed classes should develop an intense hostility to the culture; a culture, whose existence they make possible by their labour, but in whose resources they have too small a share. In such conditions one must not expect to find an internalization of the cultural prohibitions among the suppressed classes; indeed they are not even prepared to acknowledge these prohibitions, intent, as they are, on the destruction of the culture itself and perhaps even of the assumptions on which it rests. These classes are so manifestly hostile to culture that on that account the more latent hostility of the better provided social strata has been overlooked. It need not be said that a culture which leaves unsatisfied and drives to rebelliousness so large a number of its members neither has a prospect of continued existence, nor deserves it.

~Freud, The Future of an Illusion -

Could we be living in a simulation?↪Benj96 What difference would it make to our existence whether or not "we live in a simulation"? — 180 Proof

Philosophically, this seems the soundest approach. If reality in general is "of the nature of a simulation" then that doesn't add or subtract anything from the idea of reality as it affects or is affected by us.

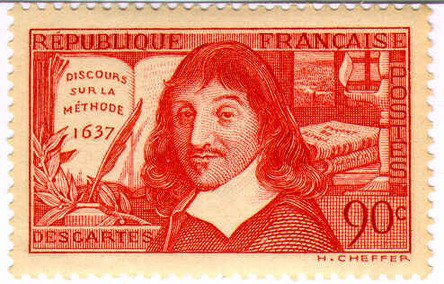

On the other hand, this sense doesn't seem to cover what is meant by simulation, which is something that is done or made by someone. So the next logical step in a simulation hypothesis would seem to be the Cartesian demon. In that case, I suppose the possibility arises that we can in some way escape or transcend the simulation. Perhaps in the sense that one seeks to transcend Samsara. -

Is "evolutionary humanism" a contradiction in terms ?Evolutionary humanism I think views humanity as a kind of apex of naturalism. This certainly fits my perspective.

-

What is the Idea of 'Post-truth' and its Philosophical Significance?The most productive hypothesis seems to me to assume that belief in truth has positive merits. What the exact nature of those merits is is what we learn.

-

What is the Idea of 'Post-truth' and its Philosophical Significance?

But whatever is the truth, you only get as close to it as "believing this true."

So how can you ever be confident in the motivation behind your own beliefs? -

What is the Idea of 'Post-truth' and its Philosophical Significance?So, to what extent can truth be explained logically, or empirically, or in terms of values and, to what extent does the idea of 'post-truth capture fragmentation in philosophical understanding? There are threads which explore the logical aspects of truth, but I am intending this to be more about the meaning of truth and how this comes into play in values. — Jack Cummins

Presumably, our values are what "drive" us - that is, what supply the motive power to what we actually do do in the world. I'd assume that there is a correlation between the awareness of the correspondence of one's values with something true, and the motive force there derived. To the extent that our values are based in fantasy, it'd be unlikely that we would actualize them. Truth really is the only pragmatic option. -

Is it possible ...to make someone understand what you yourself don't understand? — Agent Smith

If your actions serve as an example, then someone else could learn a principle which you yourself do not grasp. For example, if you poke your hand in the fire and withdraw it in pain, clearly you did not understand the meaning of fire, but I could grasp it by observing you. -

Do the past and future exist?The now has no duration. So anything that exists in time (diachronically) must have both a past and a future.

-

If Death is the End (some thoughts)Matter continuing doesn't have to do with conscious existence continuing. — TiredThinker

You might be surprised to hear that there are schools of thought that do not concur with your belief. -

How does a fact establish itself as knowledge?Facts are truths about something, an event, an object, people, so on. When they're discovered, they become knowledge. Facts are independent of a knower, knowledge, on the other hand, is not. — TheMadFool

Maybe independent of any specific knower, but not of being known or knowledge in general. I think that is how Peirce would describe the relation.

To me, they seem essentially synonymous or mutually dependent terms, maybe corresponding to the noesis-noema relationship. -

What motivates the neo-Luddite worldview?Technology as a symbol of evil and its role in the total destruction of our world is a fairly appealing narrative. And Back to Eden solutions have long been popular. Technology seems to magnify all that is terrible about humans - from pesticides to nuclear bombs, chemical weapons to plastic bags and climate change. It can be argued that technology has robbed the world of its charm, displaced people of their jobs and suggested an apocalyptic future for us that is even more horrifying than religious end times. We don't need a theorised position to understand this. — Tom Storm

Yes, all of this.

If you think of knowledge from a holistic perspective, it seems self-evident that our economically-driven societies have over-emphasized technical knowledge at the expense of moral and social. Until we are able to catch up in these other dimensions of knowledge, technology may indeed pose more dangers than it offers benefits. This I would say is the underlying motive. -

Science as MetaphysicsEveryone has a metaphysics after all, even if they dislike it. — Manuel

Yes, as does science, implicitly. That is the gist. -

If Death is the End (some thoughts)Nothing is absolutely created or destroyed, it only changes form.

When a star explodes, its atoms continue, and their trajectory reflects and continues that of the star, including the added effects from the event of its demise. In fact, if you view the star as a gravitational phenomenon from far enough away, it has a very similar profile before it has actually ignited and after it explodes. -

Is the multiverse real science?Is the multiverse science fiction only? Sabina seems to think so. — TiredThinker

As I mentioned in another thread, I see the multiverse concept as indicative of the emergence of a new scientific paradigm, coinciding with the increasing reliance of science on modeling and simulations. Which relates to the attempt to study/quantify/contextualize phenomena at an ever-increasing level of systemic-complexity. It would fit with what Popper calls a metaphysical research program. -

Science as MetaphysicsMore on point

[The metaphysics of science is] the philosophical study of the general metaphysical notions that are applied in all our scientific disciplines....This modal suggestion, that the metaphysics of science is an investigation of the metaphysical preconditions of science, has rather a Kantian flavour. But arguably, the idea that certain metaphysical phenomena are necessary for science was present in ancient thinking, as we will now see.

What is the metaphysics of science, Mumford & Tigby

If metaphysics (qua ontology) is the science of being, then it must have universal relevance. Frankly, there are a lot of terminological niceties in philosophy that give rise to a great variety of competing interpretations. The fact that this is so means that anyone who argues vehemently from some terminological standpoint (such as propositional logic) is really only appealing to lack of consensus as an authority. -

Science as MetaphysicsThe relationship between metaphysical research programs and scientific theories is pretty complex, I'll give you that.

This looks interesting, but it's pretty lengthy. I've only skimmed it.

Criticism and the methodology of Scientific Research Programs -

Science as MetaphysicsMath is intriguing.

Did you know that quite recently, scientists were able to create an entirely new phase state of matter that resists quantum decoherence by bombarding atoms in a quantum computer with a laser pulse sequence based on Fibonnaci numbers? Now that is math for you, try explaining that!

New phase of matter -

Science as MetaphysicsAlso, in a sense the machine becomes part of a model/simulation consisting of the measurable and the potential measurements....

-

Science as MetaphysicsAn experiment is performed. A machine registers the outcome. This is when the "collapse" occurs. An hour later a scientist reads the measurement - his reading doesn't mystically create an answer. — jgill

Inasmuch as the machine was created and deployed by human intention, I don't think this successfully detaches the observer from the event, do you? It's definitely interesting. -

Science as MetaphysicsYou don't make a case for "science as metaphysics" – besides, the phrase seems incoherent insofar as the latter consists of categorical statements (ideas) and the former hypothetical propositions (explanations). :chin: — 180 Proof

This seems a gross oversimplification that does justice to neither. -

Forced to be immoralYou must be a very empathetic and generous person to put yourself in this position. It amazes me that the people with very limited resources are often so much more generous and kind than those with much and to spare.

I would hope to have the courage to continue to offer my support (in your place) and achieve the best outcome before suffering personal setback, but I can't honestly say I would do. I am glad there are people like you in the world, it is undoubtedly a better place because. If I were the person deciding to evict you I certainly wouldn't do that, even if that meant problems for me. Could you dialog with your housing agency to try and pre-empt that problem? -

Taxing people for using the social media:I think that the problem should be approached at the more general level of corporate accountability. Dramatically increase the scope of government to regulate corporate actions in anything that pertains to immediate social welfare - negative environmental impacts (externalized costs), cost of necessities (food, shelter). Then better regulation of the internet - insofar as that is a product of corporate interests - is just one more step in the right direction.

-

Ego/Immortality/Multiverse/Timelinesmaybe is the reason that we are always living in the present. — Persain

Yes. As I like to think of it, it is never not now.

I'm sure your descriptions match the inspiration of pantheists throughout time. Somehow, being born to awareness in any now links you to awareness in all nows. -

Lucid DreamingIf you undertake a dream journal, and thoroughly and regularly document your dreams, your dreams will grow in extent and clarity (at least your recollection thereof), and you will naturally achieve lucid dreaming. I have done it, the results are quite remarkable.

-

Currently ReadingCritique of Instrumental Reason

by Max Horkheimer

Silas Marner: The Weaver of Raveloe

by George Eliot -

Having purpose?What does it mean to give oneself purpose? — TiredThinker

Extending one's concerns beyond the limitations of the self. We are fundamentally social beings. Being stranded on an island of self-indulgent thoughts and actions can only lead to isolation. Believing that our actions contribute to an overall good, on the other hand, can be very rewarding in and of itself. -

Authenticity and Identity: What Does it Mean to Find One's 'True' Self?It was attributed to me by Pantagruel. — ArielAssante

It was never attributed to you, it was made by me, Agent Smith misread the post, which was clear enough.

And, FYI, mindfulness is not a new idea but is, in fact, one of the core principles and techniques of Buddhism.

Accuracy is so important, isn't it? In fact....mindfulness. Wow. -

Authenticity and Identity: What Does it Mean to Find One's 'True' Self?Living mindfully. :rofl:

-

Authenticity and Identity: What Does it Mean to Find One's 'True' Self?I think mindfulness is the optimum state of mind.

-

Authenticity and Identity: What Does it Mean to Find One's 'True' Self?Bottom line, when we get all of our ducks in row, at least temporarily, there can be a “feeling” of being ‘without any kind of internal or external deception or equivocation’. That is a very powerful incentive not to delve further and most people do not. — ArielAssante

So our ducks can never really be in a row?

Pantagruel

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum