-

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"I thought he wanted to show that one can demonstrate belief without it being belief that A. — frank

What I had in mind:

X believes (placeholder)

What kind of thing goes in (placeholder), can it only be a statement? That's what characterising belief as only an attitude towards statements would commit someone to.

I'm trying to suggest that (placeholder) can also be stuff that happens. Not stuff that happens that can be described at some time later in a way that turns out to be logically equivalent to the event, not stuff that happens that occurs along with an intention towards a statement, just stuff that happens.

I think getting at that by an appeal to some Bayesian neuroscience model shows:

A) There's some scientific precedent for characterising beliefs as targeting non-statements.

B) The eye movement example I think is a concrete example that shows we are acting on perceptual expectations that are not perceptual expectations regarding statements.

C) Going through something very obscure was an attempt to stop @Banno playing "I can turn that into a statement" and "What is it that you cannot say?" moves. Not that it did much good, as the former immediately happened. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"...which are statements. — Banno

Only if you can assess the weight of a statement! -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"You might be skirting about Bayesian analysis, which hangs on belief. What you describe is reminiscent of the function of neural network; neural networks are described in Bayesian terms. But look with care and you will see that Bayesian analysis uses belief as a propositional analysis. — Banno

Assume there's a completely accurate Bayesian model of perception, its perceptual expectations in the model might be statable in a propositional form; like an equation; but that does not establish that their beliefs regard statements. On the contrary, what their beliefs regard are parameters; environmental, bodily and contextual factors; rather than statements regarding them. That is, perceptual expectations regard actions, environmental and bodily states and contextual factors. If they count as beliefs, then they are excellent examples of beliefs which do not regard statements; they regard things like heart rates, warmth, sound... not statements about them. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"No, you havn't. YOu've just presented some fumbling words about faces... — Banno

Absolutely fumbling, because (1) the process by which my eyes forage someone's face to produce a stable image of their face occurs sufficiently quickly that no statements are generated within it and (2) because it's a terrible description of an eye movement as a realisation of a mathematical model that is currently promoting eye movements towards where a new facial feature is expected to be, the sense of "belief" there might be rendered as "I believe there will be facial feature X if I look there next", but that belief is held - in the sense of being a perceptual expectation - without being directed toward the statement. At best, the statement is added on afterwards (and it need not be, typically isn't).

If you're happy that it can be described post hoc as "I believe there will be facial feature X if I look there next", I would remind you that the statement has only been added post hoc, and that the perceptual expectation both concerns the face and does not involve any translation into a statement at all at the time. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"You've just greatly enlarged the scope of belief... — Banno

All that's required is a single example of a belief that does not regard a statement. I gave you an example of a process of forming beliefs that do not regard statements.

Do you really form a belief that you will now look at your keyboard, and then look at your keyboard, or do you just look at your keyboard? — Banno

You're parsing it in terms of beliefs which can be turned easily into statements in English. Beliefs in the above sense are more similar to: "highly weighted present visual information fits best into nose category which is anticipated to belong on a face therefore since previous experience of faces entails they are shaped in such and such a configuration and their salient features are expected to be in configuration Y promote eye movement towards expected location (given recalled face information) of salient facial features assuming they are in configuration Y", and that's an inaccurate post hoc rendering gesturing towards the process, rather than a verbatim statement of what occurs.

Are you going to posit that any action one performs is actually a belief? — Banno

Nah, I think any action involves belief formation in the above sense. They occur before we delineate actions post-hoc into linguistic categories too!

And I appreciate that that is the common use in philosophy, belief as a propositional attitude, but that's not the common use everywhere; what a neuroscientist or psychologist means by belief can be much different. Why accept that beliefs only concern statements just because philosophers tend to use the word that way?

It could turn out that the example of beliefs I gave is a misnomer, but it's equally a common usage! Beliefs as perceptual expectations. I don't see why anyone should accept "philosophers use the word this way" as an argument that it must be used that way, do you? Nevermind "philosophers use the word this way" as an argument for why their use adequately describes the phenomenon in question. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"I don't see how. Any belief is a belief that... and the "that..." is always a proposition. — Banno

Question begging! That only describes a belief which regards a statement. Were it you'd proved that...

What more argument could you want? — Banno

There are counterexamples.

(1) Someone looking at a face forms beliefs regarding where to look next based on where they have looked.

(2) Those beliefs do not get translated into statements regarding facial features, it's doubtable that they even could be - the process of forming them occurs sufficiently quickly that no intention towards a statement forms, an agent having an attitude towards a statement just doesn't have to be part of the process.

So there's a sense in which a belief need not regard a statement, that breaks the chain of equivalences; beliefs may regard events (expected events), rather than statements or descriptions of events.

If you do the thing where you ask me to state a belief which can't be translated into language, I'd point out to you that that's very disingenuous, as I've already given you an example of a class of beliefs which do not regard statements. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"

Burden of proof switching. If you give an argument that beliefs can only concern statements, I'll engage more. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"

I believe that my cup is behind my laptop. Is that:

A) a belief directed at an event involving the cup

B) a belief directed at the statement "my cup is behind my laptop"

C) A&B both describe the same event

D) fourth option not covered.

If B), how does my belief about the cup become translated into a belief about a statement which refers to the cup without them becoming events of different types (cup regarding beliefs, statement regarding beliefs)?

If C) how do the two describe the same event? Are the two procedurally equivalent - does an agent's act which forms a belief regarding the cup always manifest as a belief regarding a statement about the cup with the event the belief concerns being the propositional content of the statement regarding the event?

If it's the propositional content of the statement that renders the two equivalent in that manner (the event of my cup being behind my laptop being the propositional content of "my cup is behind my laptop"), the statement which states it is only important insofar as it's a statement of an already held belief which actually regards an event. Every belief can be stated doesn't imply every belief regards a statement. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"But a belief is still an attitude towards a proposition. — Banno

Would be a good thread. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"I have a divergent take on that, since after Davidson I'm not particularly happy with the notion of modelling — Banno

I guess this is because representation mechanisms can sit pretty uneasy with direct realism?

I think it's hard to have a notion of representation playing around in a philosophy of mind without sliding into Cartesian intuitions (mental represents physical, split them up like subject states representing object states), but I do think Dennett manages to have a representational account of perception without being a Cartesian; the thing doing all the representing is a bodily process' pattern, that matches environmental patterns in some way, so there's no mental/physical event distinction in the ontology for the Cartesian distinction to attach to (a consequence of characterising experiential properties as "extrinsic relational properties"). -

Where Lacan Starts To Go Wrongbut I I feel like the rebuttal is that Lacan didn't mean literally a mirror* (and, if he did mean it literally, it can be recuperated & he knew all along & either recuperated it himself or waited for commentators to recuperate it) but what he meant was some unified 'thing' that the inchoate infant projects wholeness onto and says 'this is me.' As Number2018 was saying, this could be a 'me' or a 'you' or an 'i' -- all the stuff we can associate with what Althusser calls 'interpellation.' — csalisbury

Aye I get that. I was driving at the same thing you've been talking about with my question. Removing the aspects of the theory which look like they should be taken literally makes it just "one interpretive device among others", rather than a structure you'll be compelled to believe by its power to facilitate description of stuff that happens.

Gesturing towards "a decent analogy is how ideological production produces subjectivities", kinda names the space the phenomenon occurs in, but doesn't pin down an account. And if you want an account that's tied to an event, hollowing out the literal aspects of the theory won't do - at one point you care that it's really happening, at one point it's devolved to a metaphor that plays a role in describing an interpretive device. -

All things wrong with antinatalismI agree but am not sure how to understand "owing someone" as a basis to accept a moral duty — Benkei

David Graeber's "Debt, the first 5000 years" has quite a lot on the relationships of debt and morality. Not a logical argument for why they must go together though! -

All things wrong with antinatalismThat's something I noticed in khaled's reasons not to help someone too. That morality is somehow transactional, something I must owe someone else. It's an interesting divide that I don't think can actually be bridged. — Benkei

I don't think people have transactional ethical intuitions in lots of circumstances; families, lovers, kids, pets, friends. If a parent's strictly transactional with a child something's gone very, very wrong. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"The right approach is to reject the entire Cartesian framing. The human being (interacting in the world) is the relevant agent here, not minds or brains. We see things because we have eyes (and brains), not because our brain projects things on a virtual screen for us. — Andrew M

I think there's a pretty strong alliance between that perspective and embodied cognition approaches, though there's a rabbit hole to go down regarding how much of embodiment is the brain's doing. Do you think the role of the brain can be emphasised without falling into the Cartesian trap?

I think it can, so long as the image of the brain producing output mind states as distinct phenomena from their production is discarded. Body patterns as environmental patterns. Refusing to put events involving an agent on a privileged ontological stratum - like as a separate substance (a "res cogitans") or aspect of substance (an "infinite mode" or "attribute").

As an aside, I also think it's a separate kind of question from discussions of superveniance; as "the mind supervenes on physical states" doesn't tell you much about which conception of the mind is supervening on which conception of the physical.

Pretty much. The use of those terms reinforce the Cartesian theater such that its difficult to understand that there can even be an alternative. Per Ryle's ghost in the machine metaphor the materialist, in rejecting the ghost, simply endorses the machine (where physical things are external, third-person, objective). But that still accepts the underlying Cartesian framing and so doesn't resolve anything. — Andrew M

This makes a lot of sense to me (maybe). In what way do you believe conceptualising things in terms of mental and physical phenomena can propagate or reinforce a Cartesian perspective? -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"This is the key to the issue I have with committing to it. I'm not sure though. Do 'games' exist despite only having a family resemblance, or do we only commit to 'activities' with 'games' being a functional term, a speech act which achieves some task in context but doesn't refer? I'm inclined to think of more and more of language as speech acts rather than sortal terms, but there may be limits to this tendency. — Isaac

If the issue turns on whether patterns summarising and aggregating other patterns are real, I don't think the dispute is rooted in neuroscience. If the issue is specifically with emotions being natural kinds and whether there are neural correlates for those natural kinds, I think Barrett's critique applies. I believe those are very separate issues; the first is something like a nominalism/realism dispute, the second concerns modelling emotion*accurately.(or perception+interoception)

Do you believe it is accurate to say, according to the conceptual act theory of emotion (the Barrett paper you linked earlier and I reread) that while there are no neural correlates that match the aggregate state of "anger", there are neural correlates that match conceptualising (summarising inferentially) sufficiently similar neural correlates together with "anger"? — fdrake

Yes, so long as we see 'sufficiently' as culturally mediated. I think interoception features are no different to perception features (which is the motivation for Barrett's collaboration with both Friston and Seth), so your list of four individually underdetermining variables is no less appropriate here than it is with perception. The cultural/linguistic priors were the missing element in the effort to map neural states to phenomenological reports. — Isaac

This exchange makes me believe you do commit to neural correlates for states that can be said to be like anger or, "angry", so long as those are understood in terms of the conceptual act theory of emotion. If having a neural correlate suffices for the existence of a state, and we grant Barrett's work, that gives us commitments to neural correlates of emotions as situated conceptions. So you are committed to emotions as situated conceptions, no? -

Validity and Soundness in syllogisms of deductive argument1. Neither valid nor invalid — TheMadFool

IEP article on validity and soundness (a peer reviewed open access online philosophy encyclopedia, @S100).

A deductive argument is said to be valid if and only if it takes a form that makes it impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion nevertheless to be false. Otherwise, a deductive argument is said to be invalid. — IEP

You can see from the definition that all deductive arguments are either valid or they are invalid. No in betweens, no exceptions.

2. Both premises true

3. The conclusion is either true or false — TheMadFool

If something satisfies those two conditions, that both its premises are true and its conclusion might be false, that would be an invalid argument with two premises.

It's not the case that inductive arguments are neither valid nor invalid. They're all invalid. — TheMadFool

:up: Inductive arguments are deductively invalid, yeah*. That plays a part in setting up Hume's Problem of Induction.(will typically be, they may be valid if you happen to have observe all instances of the class you're inferring about) -

Validity and Soundness in syllogisms of deductive argument

If @S100 is examined on the material - their post begins with a lengthy quote from an A-level textbook in philosophy - they'd be examined on questions regarding deductive logic. The A-level textbook quote begins:

"Two key terms that you need to understand in relation to deductions and other

forms of argument are ‘validity’ and ‘soundness’. Validity relates to the form of

the argument. Soundness relates to an argument’s premises and its form."

"Deductive arguments have a form which is valid, which just means that if the premises are true, the conclusion must also be true." — S100

Other modes of inference than deductive logic are irrelevant to the question asked by the OP about the A-level textbook examples.

tl;dr for legwork: the second definition of "neither valid nor invalid" the OP references combines badly with the A-level textbook definition of validity, because "neither valid nor invalid" syllogisms in the second definition are actually invalid syllogisms by the A-level textbook definition.

The paper they referenced is dealing with a non-standard definition of validity. I chased it back through its citations (I think). The paper "Lehmann on the rules of the invalid syllogisms" is talking about validity in categorical syllogisms, and claims:

Anne Lehmann makes a distinction between valid, invalid, and neither valid nor invalid syllogisms. A valid syllogism is one in which the conclusion must be true when each of the two premises is true. An invalid syllogism is one in which the conclusions must be false when each of the two premises is true. A neither valid nor invalid syllogism is one in which the conclusion either can be true or can be false when each of the two premises is true

The first concept "A valid syllogism is one in which the conclusion must be true when each of the two premises is true" is the same as validity as discussed in the A level textbook examples.

The second concept "an invalid syllogism is one in which the conclusion must be false when each of the two premises is true" is a sub case of the invalidity concept in the A level textbook - because the conclusion must be false (by definition) when all (both) of its premises are true, it must be invalid in the sense of being able to have all true premises and false conclusions.

The third concept "a neither valid nor invalid syllogism is one in which the conclusion can either be true or false when each of its two premises is true" is another instance of an invalid argument by the A-level book definition - since the conclusion by definition can be false when all the premises are true.

Moreover, the paper of Anne Lehmann's that the article the OP found cites doesn't use the same terms for those concepts, she calls them "valid and perfect true syllogisms", "invalid and perfect false syllogisms" and "indefinite and imperfect syllogisms" respectively. Lehmann's original paper is "Two Sets of Perfect Syllogisms".

All the confusion comes down to the same word being used for slightly different things in different sources. A mangled reference to a 1973 logic note in a corner of research looking at categorical syllogisms vs a standard conception of deductive validity in an A-level textbook. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"So neuroscience says there is not an identifiable neural correlate for anger - we've looked really hard and can't find one. — Isaac

Do you believe it is accurate to say, according to the conceptual act theory of emotion (the Barrett paper you linked earlier and I reread) that while there are no neural correlates that match the aggregate state of "anger", there are neural correlates that match conceptualising (summarising inferentially) sufficiently similar neural correlates together with "anger"?

Even if the role "anger" plays is as a character in a play, that doesn't make it cease existing, it might exist with a changed interpretation (that it's no longer a natural kind with a devoted and human-wide neural mechanism for it, it's instead a contextualised inferential summary for arousal and valence). Ie, there are angers which "anger" marks as a post-processed, publicly accessible, summary.

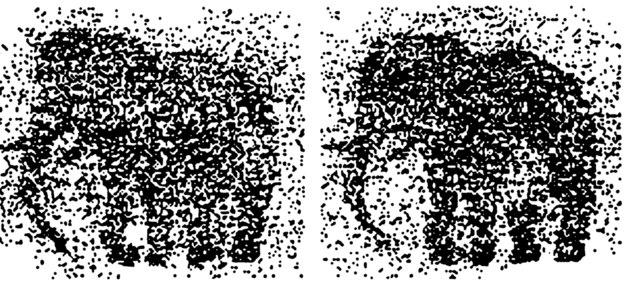

Perhaps like this picture (from Dennett's "Real Patterns") is two elephants (angers), each may be described as "an elephant" (an instance of anger), even though they are presented (simulated) differently.

(Though that the two things are distortions of the same base image might break the analogy; it could be that the neural correlates of state classes conceptualised as anger wouldn't "feel the same" if you took one process and put it into another brain - the patterns might differ quite a bit over people) -

Validity and Soundness in syllogisms of deductive argumentAm I correct in saying, Example 2 has an invalid form, and thus invalid argument according to this excerpt, because by changing the set of animals from Lizards to Cats in example 3, keeping the structure of the syllogism the same, one can clearly see the form of argument is invalid with a false conclusion. (+ and since structure/form is same for example 2, form is also invalid in 2) — S100

:up:

I agree with you! I wrote extra details if you're interested.

If you want to show an argument is invalid, you can do that by finding a way for all its premises to be true and its conclusion to be false. Looking at example 2 in that context:

P1 All bunnies are mammals

P2 Speedy the lizard is not a bunny

C Therefore Speedy is not a mammal — Example 2

P1 is true, P2 is true and C is true, but the argument is invalid, why?

The A-level book you quoted substituted in "Wilbur the cat" for "Speedy the lizard" to obtain:

P1 All bunnies are mammals

P2 Wilbur the cat is not a bunny

C Therefore Wilbur is not a mammal — Example 3

P1 is true, P2 is true but C is false.

So the argument is invalid. Since an example of the same argument form was found that had all true premises but a false conclusion.

Some more detail:

The form of an argument doesn't care about who or what specific entities it's talking about, just the relationships between them. You can write down the form of an argument using labels for the things in the statements you make Eg:

P1 All Xs are Ys.

P2 z is not an X

C z is not a Y.

You can recover example 2 by substituting in bunnies for X, mammals for Y, and Speedy the lizard for z.

You can recover example 3 by substituting in bunnies for X, mammals for Y, and Wilbur the cat for z.

That substitution is just like substitution in GCSE (if that's still a thing) algebra!

If an argument is valid, you can substitute in whatever you like for the entities mentioned in it - regardless of what you substitute in, for a valid argument if its premises are true its conclusions must be true.

That presentation gives the argument form example 2 and 3 share. It's invalid, as you've already seen. Wilbur the cat ( z ) is not a bunny ( X ), but Wilbur the cat ( z ) is in fact a mammal ( Y ). -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"I'm not entirely sure what you mean here. — Isaac

Probably because I was misinterpreting you. I thought you were construing the lower level "upwardly mobile" signals as being uninfluenced by salience+categorisation in their entirety, rather than being relatively less influential in their formation when compared to hidden state values (prior+task acting down and generating noise minimising expectations, hidden state induced discrepancies acting up to create noise).

The rest of the perceptual event stuff was to embed a single update step in the history of its update steps; which would restore instantaneous dependence on salience+categorisation through the priors+task parameters even if the upward acting signal wasn't salience+categorisation influenced in its "measurements" of the hidden state values. In other words, why the noise took those values and how the noise is incorporated is still prior+task dependent, so salience and categorisation play a role.

Seeing as you already agree with that (I think) and I was addressing a misinterpretation, I don't think it's relevant.

The model they use to handle the banana (knowing his soft it is, how heavy...) is informed by priors from the entire previous experience, but at the time of the perception event (thinking about a cortical level higher than a single saccade here), the two are not connected. — Isaac

I would expect that larger saccades do involve higher cortical levels, since they're informed by the emerging concept of what has been foraged already (see start of face, look for rest of face). Within fixation microsaccades probably don't, they seem more similar to heartbeats to me - some low level organ function maintenance phenomenon. But people are also more likely to be aware (so a perceptual event has occurred) of larger saccades - you can even feel particularly large ones in your eyes!

If salience and categorisation do influence both dorsal and ventral signals even in the dorsal/ventral severing case, and language can influence both those signals, is the point you're making that language and culture only effect the integration of both streams because they're particularly high order processes? I guess I don't understand the link of the dorsal/ventral stream dissociations to the role language and culture play, if salience and categorisation effect both, and salience and categorisation in humans have language and culture acting on the emerging perceptual landscape through the priors. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"If you disagree, perhaps you could give a non-Cartesian example. — Andrew M

Sideline question: could you give a checklist for a position not to count as Cartesian? Just to be clear, I'm not trying to "gotcha" question you into "lol the term is meaningless", since non-Cartesians are good company, but I'd struggle to write a list.

I have some more questions in that direction:

Does Cartesian = adhering to subject/object and the attendant distinctions (internal/external, mental/physical)?

Would you throw a doctrine like "environmental patterns are represented by mental patterns + mental pattern = neural pattern" in the Cartesian bin because what it's trying to reduce (mental patterns) still adheres to a Cartesian model?

Can you do an "in the body/in the environment" distinction without being a Cartesian? -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"If anyone wants to read a paper on how Dennett treats the folk psychology categories ("pain", "spicy" etc) as a useful models without giving them the same strength of ontological commitment he gives to neurons, electrons etc, his essay Real Patterns seems illuminative.

-

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"Do you fell up to summarising? — Banno

It would be an even longer post to write, I think! -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"I see what you mean here. If at any given time the only variable that really is 'varying' in the system is the hidden state, then we can appropriately talk about a direct causal relationship. Like triggering a pinball, the various flippers and pegs are going to be determinate of it's path, but they're fixed, so right now it's path is directly caused by the strength of the trigger? — Isaac

@Banno (because "seeing as" and "seeing an aspect")

Yeah! That's a good analogy. Translating it back to make sure we're concordant: the priors=flippers, task parameters =pegs and the strength of the trigger = hidden states.

So, if we want to answer the question "what are people modelling?" I think the only answer can be 'hidden states', if they were any less than that then the whole inference model wouldn't make any sense. No-one 'models' and apple - it's already an apple.

I think what I claimed is a bit stronger, it isn't just that the hidden state variables act as a sufficient cause for perceptual features to form (given task parameters and priors), I was also claiming that the value of the hidden states acts as a sufficient cause for the content of those formed perceptual features. So if I touch something at 100 degrees celcius (hidden state value), it will feel hot (content of perceptual feature).

I think a thesis like that is required for perception to be representational in some regard. Firstly the process of perceptual feature formation has to represent hidden states in some way, and in order for the perceptual features it forms to be fit for purpose representations of the hidden states, whatever means of representation has to link the hidden state values with the perceptual feature content. If generically/ceteris paribus there failed to be a relationship between the hidden states and perceptual features with that character, perception wouldn't be a pragmatic modelling process.

I'd agree here. Do you recall our conversation about how the two pathways of perception interact - the 'what' and the 'how' of active inference? I think there's a necessary link between the two, but not at an individual neurological level, rather at a cultural sociological level. All object recognition is culturally mediated to an extent, but that cultural categorising is limited - it has functional constraints. So whilst I don't see anything ontological in hidden states which draws a line between the rabbit and the bit of sky next to it, an object recognition model which treated that particular combination of states as a single object simply wouldn't work, it would be impossible to keep track of it. In that sense, I agree that properties of the hidden sates have (given our biological and cultural practices) constrained the choices of public model formation. — Isaac

Just to recap, I understand that paragraph was written in the context of delineating the role language plays in perceptual feature formation. I'll try and rephrase what you wrote in that context, see if I'm keeping up.

Let's take showing someone a picture of a duck. Even if they hadn't seen anything like a duck before, they would be able to demarcate the duck from whatever background it was on and would see roughly the same features; they'd see the wing bits, the bill, the long neck etc. That can be thought of splitting up patterns of (visual?) stimuli into chunks regardless of whether the chunks are named, interpreted, felt about etc. The evidence for that comes in two parts: firstly that the parts of the brain that it is known do abstract language stuff activate later than the object recognition parts that chunk the sensory stimuli up in the first place, and secondly that it would be such an inefficient strategy to require the brain have a unique "duck" category in order to recognise the duck as a distinct feature of the picture. IE, it is implausible that seeing a duck as a duck is required to see the object in the picture that others would see as the duck.

Basically, because the dorsal pathways activities in object manipulation etc will eventually constrain the ventral pathways choices in object recognition, but there isn't (as far as we know) a neurological mechanism for them to do so at the time (ie in a single perception event).

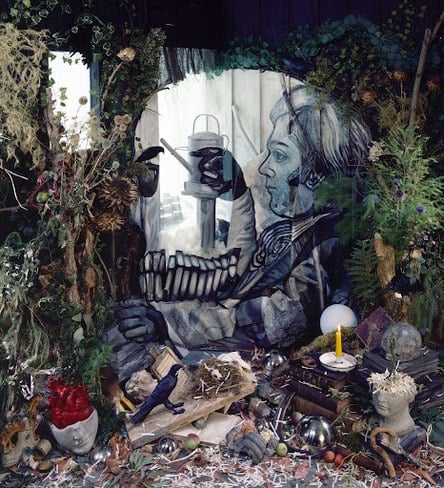

I think we have to be quite careful here, whatever process creates perceptual features has the formed perceptual features that we have in them - like ducks, and faces. I know the face example, so I'll talk about that. When someone looks at something and sees a static image or a stable object, that's actually produced by constant eye movement and some inferential averaging over what comes into the eyes. When someone sees an image as a whole, they first need to explore it with their eyes. Eyes fixate on salient components of the image in what's called a fixation point, and move between them with a long eye movement called a saccade. When someone forms a fixation point on a particular part of the image, that part of the image is elicited in more detail and for longer - it has lots of fovea time allocated to it. Even during a fixation event, constant tiny eye movements called microsaccades are made for various purposes. When you put an eye tracker on someone and measure their fixations and saccades over a face it looks something like this:

(Middle plot is a heat map of fixation time over an image, right plot has fixations as the large purple bits and the purple lines are saccades)

But what we see is (roughly) a continuously unchanging image of a face. Different information sources*of different quality(fixation points, jitter around them)*of different hidden states(whether the light is hitting the fovea or not)[/url] at different times (fixation points are a sequence)*being aggregated together into a (roughly) unitary, time stable object. Approximate constancy emerging from radical variation.(light reflected from different facial locations of different colours, shininess)

That indicates that the elicited data is averaged and modelled somehow, and what we see - the picture - emerges from that ludicrously complicated series of hidden state data (and priors + task parameters). But what is the duration of a perceptual event of seeing such a face? If it were quicker than it takes to form a brief fixation on the image, we wouldn't see the whole face. Similarly, people forage the face picture for what is expected to be informative new content based on what fixations they've already made - eg if someone sees one eye, they look for another and maybe pass over the nose. So it seems the time period the model is updating, eliciting and promoting new actions in is sufficiently short that it does so within fixations. But that makes the aggregate perceptual feature of the face no longer neatly correspond to a single "global state"/global update of the model - because from before it is updating at least some parts of it during brief fixations, and the information content of brief fixations are a component part of the aggregate perceptual feature of someone's face.

Notice that within the model update within a fixation, salience is already a generative factor for new eye movements. Someone fixates on an eye and looks toward where another prominent facial feature is expected to be. Salience strongly influences that sense of "prominence", and it's interwoven with the categorisation of the stimulus as a face - the eyes move toward where a "facial feature" would be.

What that establishes is that salience and ongoing categorisation of sensory stimuli are highly influential in promoting actions during the environmental exploration that generates the stable features of our perception.

So it seems that the temporal ordering of dorsal and ventral signals doesn't block the influence of salience and categorisation on promoting exploratory actions; and if they are ordered in that manner within a single update step, that ordering does not necessarily transfer to an ordering on those signal types within a single perceptual event - there can be feedback between them if there are multiple update steps, and feedforwards from previous update steps which indeed have had such cultural influences.

The extent to which language use influences the emerging perceptual landscape will be at least the extent to which language use modifies and shapes the salience and categorisation components that inform the promotion of exploratory behaviours. What goes into that promotion need not be accrued within the perceptual event or a single model update. That dependence on prior and task parameters leaves a lot of room for language use (and other cultural effects) to play a strong role in shaping the emergence of perceptual features. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"Yep, I think that actually a good way of putting it. I've described myself as an indirect realist before, but these are not terms I have a in-depth knowledge of, so I'm not attached to them. My question was really just getting at the issue of how we define the boundaries of a 'perceptual system'. Where does the perceptual system end and some other system take over (even if only in theory to show that it never does)? If we just say that the boundaries of the perceptual system are the edge of the Markov Blanket, then your version of direct realism is true, but only by definition (ie if some other process intervened between the hidden state and the perceptual system it would, by definition, either be a hidden state itself or part of the perceptual system). — Isaac

I think that's about what I meant. Don't come away from what I've said with the idea that "how fdrake thinks about direct realism" is canonical though. For me directness is just a lack of perceptual intermediaries. I think people who are professionally direct realists have different commitments to that. For some it seems to come down to mind dependence vs mind independence of what is perceived*, and there's also an element of whether (and how) perceptual features are real.(and clearly that intersects with the perceptual intermediary debate, mind dependent perceptual intermediaries are strongly intuition pumped by arguments from dreaming/illusion)

So to get a Cartesian Theatre problem (in order to disprove it empirically rather than definition-ally) we'd have to say that the creation of 'the play' out of some hidden states was not part of the perceptual system - the perceptual system was the bit watching the play. If we say the play-making mechanisms are part of the perceptual system then the system is in direct causal relationship with the hidden states (it's just that the description of the perceptual system is wrong). I don't see anything wrong here at all, I only wanted to clarify which way you were looking at it.

Aye. I think that's true. I think the directness claim (no perceptual intermediaries) is an easy consequence of any active perception account which includes environment exploring actions as a component of perception. If you pick something up, there has to be causal contact between the mass of the thing how you sense and adapt to loads. If "how you sense and adapt to loads" in total is labelled as (a part of) perception, then perception (as a process) is in direct causal contact with the world.

Though devil's advocating it, that direct causal contact could be between a perceptual intermediary and the mass. But I think that requires the Cartesian Theatre metaphor to be true - it would only be an intermediary if the perceptual intermediary was submitted to some distinct faculty or process*. So that's going to turn on whether it's more appropriate to emphasise action in perception than a "submission" process to consciousness as a distinct faculty.(note: not talking about passing inhibited patterns of signals around in the process of feature formation, the more cognitive aspects are lumped in)

Without that submission process and with an active account of perception, directness in the sense I meant (I think) is implied. It is almost true by definition (within the account of perception), but whether it's supported in practice turns on the behaviour of the account using it and accounts which don't use it. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"Yes, but again with caveats I'm afraid. I presume you're talking about mutually exclusive variables to an extent (again with ceretis paribus). In normal circumstances all four would collectively determine - ie there's no other factor - I want to leave aside the thorny issue of whether there might be some random factor for the moment as I don't think it's relevant (my gut feeling is that there might be at least a psuedo-random one resulting from the chaos effect of such a complex system). — Isaac

I definitely should've highlighted that I was claiming in normal circumstances items (1) to (4) do collectively determine the process of perceptual feature formation. I do think they're mutually exclusive components of perceptual feature formation - they have different names and play different procedural parts - but all four variable types are informationally and causally connected so long as there's an agent actively exploring an environment during a task. When I said the types are connected, I mean some variable that belongs to each type is connected to a variable that belongs to some other type, though it need not be a direct contact in order for it to count as connected. In the network of variables in the model, that would correspond to there being a path from a variable in every type to some variable in every other type, rather than having every variable in each type being a neighbour of some variable in each other type. If that's super dense, it's the same as colouring task parameter and prior variable nodes red and hidden state nodes blue in whatever variable network the model has then saying "there's at least one arrow between the red ones and the blue ones".

So they're "mutually exclusive" in terms of being qualitatively distinct variable types in the variable network of the model, but they're not thereby causally or statistically independent of each other since they're connected.

We may have got crossed wires. What I mean by saying that the thing modelled is 'the apple' which is a public model, is not intended as an entanglement of some hidden state with the public model. It's a limit of language (which is what I was trying to get at in my edit). The process of 'seeing' could be seen as essentially that of fitting sensory data to priors (filtering of priors being task dependant). So the meaning of 'I see an apple', might be 'the sensory input best fits the public model of 'apple'', but this is not that same as saying that we see 'model-of-apple', because that would be to make that Cartesian divide of 'seeing' into object>qualia>perception(of qualia). It's just that that's what 'seeing' is, so it's only correct to say we 'see the apple'.

If we wanted to phrase all this in terms of purely Markov Chains in the process of perception, then I don't think we can say any more than that the cause of of our perceptual feature has no name. We do not name hidden states, we only name objects of perception. — Isaac

Edit - Another way of putting this (the language gets complicated) might be to say that we do name the hidden state (apple), but that these christenings then produce fuzziness on the hidden states we could possibly refer to in any given instance of perception - so the hidden state that is in direct causal relationship with our perceptual system will be only fuzzily identified by any word we apply. I'm not sure which approach is best (if any), I don't think we've really got the linguistic tools we need to develop theories about objects of perception

I think we did get wires crossed, but I suspect we disagree on something somewhere. Maybe in the nature of that entanglement and the relationship language plays to it. One way of reading the second paragraph makes how language is used consequent of perceptual feature formation. So it would go like: hidden state -> apple perceptual features -> "I see an apple". But AFAIK there are also models*that look more like:(I think we've talked about this before on forum in the context of Barrett's work)

hidden state -> categorising of sensory inputs -> output perceptual features

hidden state -> categorising of sensory inputs -> language use

but also with:

output perceptual features -> categorising sensory inputs

and

language use -> categorising sensory inputs

feedbacks somewhere in the model. So once someone is categorising sensory inputs in a sufficiently mature way, they already have prior language use and prior perceptual feature feedforwards into the categorisation of sensory inputs.

To be clear, by categorising sensory inputs I mean a device that distinguishes foraged data generated by hidden states and aggregates them into related salient types based on previous model states. This is part of perceptual feature formation. For example, that I see the duck in the duck rabbit or the rabbit at any given time. The salience bit says I see a duck or a rabbit, not a meaningless scribble. The types are the duck and the rabbit. Categorisation is assigning something a type.

To put it starkly, it seems to me that there's evidence that language use plays some role in perceptual feature formation - but clearly it doesn't have to matter in all people at all times, just that it does seem to matter in sufficiently mature people. Language use seems to get incorporated into the categorisation aspect of perceptual feature formation.

The layout of lines on the page isn't changing in the duckrabbit, but the state of my perceptual models regarding it is varying in time - at one time the pair of protrusions function to elicit the perceptual feature of rabbit ears, at another they function to elicit a duck's bill.

So the issue of the degree of "fuzziness" associated with labelling hidden state patterns with perceptual feature names comes down to the tightness of the constraint the hidden states place upon the space of perceptual features consistent with it and the nature of those constraints more generally.

I would like to highlight that the duckrabbit stimulus can only cause model updates after its observation. So in that respect, the hidden states which are constitutive of the duckrabbit picture act as a sufficient cause for for seeing it as a duck or a rabbit, given that someone has a perceptual system that can see the layout as a duck or a rabbit. But only a sufficient cause when conditioning on the presence of a suitably configured perceptual system.

Analogy, "if it looks like a duck and quacks like a duck it's a duck", taking that way too literally, if someone observed something that quacked like a duck but did not look like a duck, on that basis alone the believer of "if it looks like a duck and quacks like a duck..." could not conclude that it was a duck. But if they then observed the thing making the quacking noise looked like a duck, they could immediately conclude that it was a duck. The "quacking" was in place already, so "it looking like a duck" was sufficient for the conclusion that it was a duck.

Translating out that analogy; we expect certain configurations to be ducks and certain configurations to be rabbits - we expect ears and rabbit faces on rabbits, bills and long necks on ducks - if you show someone who will see bills and long necks appropriately arranged as a duck a picture of a duck, they will see the duck. To be sure that's not a very complete list of duck eliciting hidden state patterns*... But I shall assume you know what I mean.(and someone who doesn't know what a duck is will probably see what we would call a duck, just not "package" those patterns together as a duck)

In summary: I think that issue boils down to whether the duckrabbit's hidden states associated with page layout cause duck or rabbit given my priors and task parameters. I think that they do. It isn't as if the hidden states are inputs into a priorless, languageless, taskless system, the data streams coming out of the hidden state are incorporated into our mature perceptual models. In that respect, it does seem appropriate to say that the hidden states do cause someone to see a rabbit or a duck, as one has fixed the status of the whole model prior to looking at the picture. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"So would what constitutes a 'perceptual system' have parameters other than the edge of their Markov blanket? I mean such that we're not simply making the above true by definition? — Isaac

This might be wrongheaded, but I think the perceptual system would not be direct if the process of perceptual feature formation didn't have direct causal contact to some hidden states. Isn't that the Cartesian theatre metaphor? We see "models" or perceive "aspects of aggregated sense data", rather than perception being a modelling relation. In those formulations, the models or the sense data are in direct causal contact with the environment, and all perception is of those things which are in direct causal contact with the environment. Two steps removed at all times (Cartesian Theatre) vs One step removed at some times (direct realism). -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"Yeah, I think you'd have to. We can't escape this and look at it from a position where I'm outside of my modelling, but I don't see that as a problem (I know some people do). I'm ultimately a pragmatist and it seems to work. — Isaac

So let's make a distinction between environmental and bodily hidden states. If a hidden state occurs as a part of a bodily system, then I'll call it bodily. If it doesn't, I'll call it environmental. Analogy, my current blood sugar level is a bodily hidden state, the position of the bottle on my desk is an environmental hidden state. Doubtlessly the two have feedbacks between them, and sometimes there is ambiguity regarding whether something is a bodily state or an environmental one.

I'm going to call whatever specifies the current overall task the body is engaged in task parameters, I'll throw in whatever task relevant actions are proposed*in with task parameters. EG, I'm currently typing, part of that is motor control, part of that is cognitive functioning, where the keys are, what I feel the need to write, those are task parameters.(but not why they are proposed as they are)

I'm going to call whatever a person's learned and is bringing to their current state from that learning - language stuff, habits, etc - priors.

And to spell out underdetermination, a system X is underdetermined by a collection of states when and only when that collection of states does not force X to produce a unique output. EG, if x+y=1, there's more than one solution to it. More metaphorically, if a corpus of evidence supports more than one conclusion, it can be said that the corpus underdetermines its conclusions.

Lastly, I'll call whatever bodily systems in their aggregate output our perceptual features (cups, pulses, warmth/cold, position, emotion etc) the process of perceptual feature formation.

Do you think the following are true:

(1) Environmental hidden states underdetermine perceptual feature formation.

(2) Bodily hidden states underdetermine perceptual feature formation.

(3) Task parameters underdetermine perceptual feature formation.

(4) Priors underdetermine perceptual feature formation.

?

For perceptual systems, (1) means something like "you need not see the same thing as someone else given the same environmental stimulus", (2) means something like "you and another person might disagree on whether 37.6 degrees celcius is normal body temperature or very hot", (3) is like "you and another person can agree entirely on the problem to solve and the solution but not do exactly the same thing" and (4) is like "you and another person bring different life histories to an event and so can interpret it differently". The possibility of those differences is underdetermination.

I think if you put the hidden states into the process of perceptual feature formation, it changes part of their causal relationship with perceptual feature formation. I think that's most clear with environmental hidden states. Putting the environmental hidden states into the process of "publicly agreed" perceptual feature formation, making them play an internal causal role, seems to make them causally fully determined by the process rather than informationally constrained and (possibly) causally partially determined by the process.

In active accounts of perception, people take exploratory actions to elicit data from their environment - that can be how your eyes track over a face to produce a stable image, picking something up and adjusting your body to distribute the load -. These exploratory actions elicit data streams nascent in the environment or cause the environment to behave differently and elicit data regarding the change - contrast exploring someone's facial features which are "already there" vs manipulating a heavy object and adjusting to distribute its load.

These exploratory actions interface with the hidden states - the layout of someone's face and its colour in the light conditions, how the heavy object responds to attempts to pick it up due to its distribution of mass, but they don't causally determine the state of the hidden state. EG, someone's face doesn't rearrange itself because it's looked at, the distribution of mass along the heavy object doesn't change when it's lifted. The environmental hidden states have their own developmental trajectory that we are perceptually exploring in an active, task relevant manner. When perception is functioning normally, though, our perceptual features do model the developmental trajectory of our environmental hidden states enough for our purposes. IE, normal functioning perception places informational/statistical constraints on the developmental trajectory of environmental hidden states, but it should not causally determine their developmental trajectory generically. Like exploring someone's face to form perceptual features of it doesn't actually change the layout of their face. That's a case of informational constraint without causal constraints.

Edit: to clarify, imagine a civil engineer's model of how a bridge bears loads is perfect, they will be able to tell exactly how much would be required to break it. If they had it in their computer, and put in inputs to the model that would collapse the bridge, the bridge would collapse. But the real bridge wouldn't collapse, it just would collapse with certainty if it was exposed to the same inputs. The model informationally constrains the development of the bridge given an input load, but it doesn't actually make the real bridge respond to a load. That'd be a situation where the model completely informationally determines the behaviour of the bridge, but has absolutely no causal relationship with the load bearing behaviour on the bridge.

When I pick up the heavy thing, I do determine its trajectory from the ground to some degree, but I don't do the whole thing - it might be unwieldy, I might bend too much, I might've overestimated the weight and pull it too high. But eventually I manage to stabilise the load. In that situation, the process of perceptual feature formation has attuned to the developmental trajectories of the heavy object and reached a fit for purpose relation - it's being held where it is stably, and I feel it being held there. That's a case of informational constraints with causal constraints. But I still don't causally determine gravity or the heavy thing's distribution of mass (hidden states) that play into the overall lifting action.

Edit2: We're in a more mixed situation than the bridge example with active perception. It's more like if the civil engineer realised that the bridge would collapse from peak Christmas traffic that year, an intervention to stop disaster would happen if the engineer told someone. That's more of the situation we're in - the models we make propose courses of action, so our models when accurate both propose worldly interventions given our current representation of the world and represent the world in some way, so they're causally connected to what they concern, but the content of the model doesn't determine how what it models will behave or develop, it places constraints on how it will behave or develop given the degree of accuracy of our model and our intervention.

I think if you throw the hidden states into the "public perception" of things, you lose the possibility of surprise and adapting to it. To be sure, there are public perceptions of hidden stateseg, but those public perceptions don't causally fully determine the hidden states(like we can agree on whether an apple is green and whether it is a more sweet or more sour variety)more eg. It might be that it looks just like a Golden Delicious but it's really a Granny Smith.(light reflection profile, pigmentation, acid vs sugar ratios)

If you make the environmental hidden states a part of the process of perceptual feature formation, you lose the ability to elicit underdetermined behaviours from them based on models; to be surprised by them at all. Since they may become fully causally, not just possibly informationally and partially causally, determined by the process of perceptual feature formation. How things look in public becomes what they are. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"↪fdrake An alternative one could take is that the model puts one in direct access with the hidden state. Not sure how tenable that is, but if you wanted to ground scientific discovery in direct perception, that's a way to do it. — Marchesk

I think directness is ultimately a question of whether there is a direct causal+informational relation between the hidden environmental states and the process of perception, not whether the whole process of perception is direct or indirect when regarding (properties of) the object. For me at least, a perceptual system is direct when there are no intermediaries between some part of it and hidden states.

Though I imagine that is unusual, since direct realists can be construed as believing when someone sees a red apple, the direct realist's perceptual system simply acknowledges that it is indeed a red apple, and there's a neat correspondence between perceptual properties and apple properties.

Yes, but less so. I don't necessarily see any reason why a model might no become disconnected from the causal state which at one time formed it, I don't think there's anything neurologically preventing that. — Isaac

I agree with that too. I think there's some ceteris paribus clause required - in normal circumstances the hidden states are directly causally connected with the perceptual process and the perceptual process is informative of the hidden states' status insofar as they are task relevant.

The apple. There's nothing more that an apple is than the publicly agreed model. It's not that there's no apple, it's that that's what 'seeing an apple is'. — Isaac

Are you throwing the hidden states into the public agreed model there? -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"The hidden state of some part of the external world. — Isaac

Here is a thing I've never managed to understand when talking with you about this. Do you agree with these things?

(1) The model's state is informative of the hidden state, but underdetermined by the hidden state.

(2) The model's state is directly causally connected with the hidden state but underdetermined by it.

(3) That underdetermination arises because of priors and task parameters.

When a hypothetical philosophical someone says "I see the apple", they're utilising the causal connection between their perceptual system and the apple. Do you believe they're seeing "apple models" or do you believe they're seeing what the apple models are modelling in the manner they are modelled (roughly, the apple)? -

Godels Incompleteness therom and QThat is incorrect. It is not the case that for every formula, either FOL proves the formula or FOL proves the negation of the formula. That result is known as Church's theorem. — GrandMinnow

:up:

Again, I was wrong.

Example: for all x P(x) => Q(x) is a statement of FOL, but neither it or its negation are provable. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"It seems not to be individuated. — Banno

:point:

Or individuated in a manner that doesn't resemble labelling classes*of similar states with the word "pain" as we usually use it.(or aggregating states based on family resemblance)

Hence doubts regarding the accuracy of folk psychology, whose truth depends upon just that kind of procedure. "This hurts!" as expletive more than description. -

Godels Incompleteness therom and QDarn. I am afraid I have to be picky again. A contradiction is not false. A contradiction is a pair of syntactic derivations, one of some statement P and the other of not-P. There is no truth or falsity in syntax. — fishfry

Fair! I think that's equivalent to a theory deriving (P and not-P) though, which is always false. IE, a theory managing to prove something that no object could make true/satisfy.

Spelling out that connection: that immediately means you've got no models. Since if a hypothetical model satisfies P then it cannot satisfy not-P. The converse also holds. Therefore there are no models of such a theory. Then it's a contradiction in the "no models" sense. So having a model immediately blocks that situation.

I edited the post again to: "if a theory proves P and it also proves not-P then it proves a contradiction". -

Godels Incompleteness therom and QBut if a system is inconsistent, it has no model at all; so the claim that a contradiction is false in every model doesn't make sense to me. — fishfry

That makes sense. I'm using terms way too loosely and wrong.

A model of a theory is an object which satisfies all that theory's true statements. Like the real numbers are a model of the field axioms. Contradictions can never be true; so a contradiction is a statement for which no model exists (by definition a model of a contradiction would make that contradiction true). If a theory proves a contradiction, then whatever would model it would also have to model that contradiction. But there are no models of contradictions. So that theory would not have a model.

I was getting confused with the idea of a countermodel - for a contradiction, every model is a countermodel.

Sorry for all the confusion. I edited the post you quoted to explain a contradiction as "(statements which are always false)" -

Godels Incompleteness therom and QI'm no expert on this stuff but every tautology has a proof. Incompleteness involves propositions that aren't tautologies, whose truth value varies with the model. For example the axioms for a group say nothing about whether the group is Abelian. The statement "xy = yx for all x, y" is true in some models and not in others. So the group axioms are not complete. — fishfry

Seems I was confused and wrong then.

To set the record straight, do you agree with this:

Edit: (0) Call a well formed formula of a system's language which can be true or false "a statement".

(1) That a tautology of a system is a statement in it that evaluates as true in every model of that system.

(2) That a system is semantically complete if there is a derivation for every tautology (every tautology is a theorem). FOL is semantically complete.

(3) That a system is syntactically complete if for every statement in it, either it or its negation is provable.

(4) A system is consistent if it proves no contradictions*.(if the theory proves P and also proves not-P then it proves a contradiction)

(5) The first incompleteness theorem says that every (sufficiently strong) system which is consistent cannot be syntactically complete.

(6) That a list of statements is closed under derivations if that list of statements contains every statement which is derivable from it.

In the context of the OP:

(7) Q is closed under first order logical derivations; which means every (first order) statement which can be derived from Q is in Q.

(8) Q contains additional structure to raw FOL - it proves more. So the completeness theorem applies to the underlying logic but not to Q. There are Q theorems which are not raw FOL theorems.

(9) Q is incomplete (if it is consistent) since Godel's incompleteness theorem applies to it. This shows that there are statements which can be made using the language of Q for which the statement and its negation cannot be proved (syntactically derived) (if it is consistent).

(9) and (7) may appear to contradict each other, but they don't, as "everything which can be proved from Q is already in Q" and "nevertheless there are things which Q can't prove" don't contradict each other. Analogy, you wouldn't expect the principles underlying Gordon Ramsey's Perfect Scrambled Eggs recipe to allow you to also cook Gordon Ramsey's Perfect Beef Tenderloin.

Edit2: and in further connection to your post, I think you were very right to hammer on my incorrect use of the word "tautology", because if Q failed to prove x and failed to prove not-x, Q could be augmented with x or not-x as an axiom, and this new system Qx would still be a model of Q's axioms, just like an Abelian group is a model of the group axioms, as is a non-Abelian group. A statement being a tautology blocks that ability to assume a model where it is false. -

Theory is inconsistentLooks like a Tarski's undefinibility theorem problem. The strategy there will probably be using the diagonal lemma to set up a derivable contradiction using K as the truth predicate - since we have that K(phi) and phi are interderivable.

-

Godels Incompleteness therom and QA list of statements is closed under first order logical consequence = everything that can be derived from that list's elements using first order logical consequence is in the list.

Incompleteness says that there are tautologies which can't be derived (as theorems). Closure says everything that can be derived is thrown in, incompleteness says there are semantic truths that can't be derived (using the relevant entailment). -

Where Lacan Starts To Go WrongRegarding the mirror stage - what about people who're born blind, though? If seeing your own reflection is a necessary event in the formation of a distinction between self and world/other etc.

-

The Lingering Effects of TortureWhat is especially important are the stories torture victims tell themselves after being subjected to abject suffering. For instance, a journalist who challenges an authoritarian regime and is taken captive and subjected to a mock execution might blame herself for getting into the situation and thus potentially orphaning her children when really she should blame the regime for being evil. Often it seems victims try to rationalize torture however they can, but these rationalizations also contribute to the lingering effects in some circumstances. — ToothyMaw

Some ways of torturing explicitly try to get their victims to want the torture or blame themselves for it, so that the torturers appear as allies and saviours.

If you isolate someone and deprive their senses, the person who isolated them can be friendly and provide relief and human contact.

If you force someone into a stress position, you give someone the experience of their own body failing, "If only I hadn't been so weak".

If you rectally force feed someone, even hunger can turn into the anticipation of humiliation and pain.

You also want to put someone into a situation where their stress response is elevated and their ability to cope with whatever torture is administered to them is diminished; like with isolation and sleep deprivation.

Modern torture techniques are designed so that the victim blames themselves for what's happening to them, so that dependence is fostered upon the torturer, and so that normal bodily processes become a source of stress. They're designed so that they engender pathological coping mechanisms, designed to promote lingering effects.

fdrake

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum