-

Naming and necessity Lecture Three.Though I would suggest that we leave the discussion for later, though. @Banno. Going through the book matters more.

-

Naming and necessity Lecture Three.

It wasn't even Evans, it was Luntley being inspired by Evans now that I'm looking at the book again - it wasn't even the book I thought it was, 'Truth, World, Content' rather than 'Varieties of Reference'.

The most important distinction Luntley leverages (I think) is roughly one between a causal chain and a chain of communication. The impact of this distinction is that a causal chain is a necessary feature to explain the relationship of referent and reference, but it is not a sufficient feature; the additional requirement is that relevant information is transmitted between name users (and people learning to use the name). There are three parts of this critique that I'll try to summarise. Before beginning though, I think it's important to note before continuing that Luntley is not a descriptivist, so the angle of attack is different from the previous ones discussed, and Luntley's objectives are thus quite sympathetic to Kripke's.

(1) One example which Luntley discusses (and I am probably missing lots of nuance in my presentation here) is when two things share a name; say we have Cicero my dog and the usual Cicero. The initial baptisms, so to speak, give the same name. Nevertheless, there are causal chains which link the use of "Cicero" when referring to my dog and "Cicero" when referring to the usual suspect, and these causal chains are distinct.

By means of an example, which Cicero am I referring to when I write: "That's Cicero"?

We don't have sufficient information to grasp in which way I am successfully referring with the above expression. This should raise some eyebrows; as this does not mesh well with a theory of successful reference which posits an insensitivity to information about the referent or the pattern of use the name is embedded within.

As the author puts this conclusion: 'Indeed, it (the causal theory - me) is an informationally sensitive account of reference, and it is the informational links you have, not the causal links, which do the work (of securing reference - me).

(2) The second part of the critique is that Kripke's theory of reference is really a theory of deferred reference. As the author puts it: "the thesis that names are rigid designators has nothing to say to the fundamental question of what it is for names to have objects as their semantic values. It speaks rather of the stability of that relation across possible worlds once it is established."

The rough argument goes like; at any given instance of reference, that instance of reference successfully refers because of its antecedent causal chain. You can keep going like this all the way back to the initial baptism. But there is a slight of hand here, the initial baptism cannot use the antecedent causal chain to account for why the name has its chosen object as its semantic value.

(3) The last part integrates the suspicions of the first two, but leans heavily on an example by Evans at the same time. Evans' example is the problem of 'Madagascar'; we inherit that name-object relation from a causal chain beginning with Marco Polo, but this was inspired by a misinterpretation of the native language, it instead referred to a part of the African mainland in that tongue. Here we have a contiguous causal chain in which the semantic value of the name changes. Of course, we can recognise that before it was one thing and after another, but this requires applying a filter of correctness to the causal chain, rather than using the causal chain itself to vouchsafe the reference. The move made here is to notice that this renders raw causal chains with no qualifiers only accidental guarantors of the name-object relation; so we have informational content at play in order to vouchsafe reference in addition to the deference to the causal chain. -

Naming and necessity Lecture Three.Rather, in so far as the referent of a proper name is fixed at all, it is by what Kripke calls causal chains, but what I might call shared use. — Banno

I'm going to try and summon @Pierre-Normand to comment on this, because they have a much better understanding of the distinctions between 'shared use' and 'causal chains' in Evans' 'Varieties of Reference' than I do, and I assume people in the thread will find it interesting. -

Another question about a syllogismJust for reassurance.

Nevertheless, it is true that 'if the square of a number is even, then that number is even', and here is a different valid argument (though not presented in the strict language of a formal reasoning system) to show it:

(A) Every number has a prime factorisation. (assumption, true)

(B) If a number, x, is equal to another number, y, squared; then the prime factorisation of x must consist solely of all the factors of y squared. (assumption, true)

(so if we have x = 144 = 12^2, then y = 12, the prime factorisation of x=144 is 12*12=3*4 * 3*4 = 3*3*2*2*2*2=3^2 * 2^4, then the prime factorisation of y must be (3*2)^2)

(C) If a number contains 2 as a prime factor, then that number is even and vice versa (assumption, true)

(D) If x is the square of a number y and is even, then y must also be even (conclusion, true, from A,B,C and since the argument is valid)

For interest, the difference between something being true (or false) and there being a valid argument which demonstrates that truth (or falsity) has really deep consequences in logic and mathematics. -

Another question about a syllogism'If the square of a number is even, then that number must be even' - this is true. But does it follow from the premises alone that:

(1) If a number is even, then its square is even.

(2) If a number is odd, then its square is odd.

?

Well, in this set up, we don't know anything about the relationship of odd and even, and we don't know anything about prime factorisations or that even means 'is divisible by 2 with no remainder'... The only premise here which is even related to even numbers and squares of even numbers is (1).

So the question becomes, can we conclude the statement: 'If the square of a number is even, then that number must be even' from the statement 'if a number is even, then its square must be even'? No. You're absolutely right to say that this is affirming the consequent. Affirming the consequent is an invalid argument of the form (P implies Q, assume Q, therefore P).

Setting it up like it appears in the Wikipedia article - our 'P' is 'a specific number is even', our 'Q' is 'the square of the number in P is even'. So (1) translates to 'P implies Q' or equivalently 'P=>Q'. Now we're tasked with arriving at the conclusion P using only the assumption Q... And we can't.

What this example highlights is the difference between an argument failing to establish a conclusion since it is invalid, and that conclusion being true or false. The take home message of this is that arguments are attempts to link premises to conclusions, a valid argument is a link that transmits the truth of premises to the truth of the conclusions, but it can still be the case that an argument makes a true conclusion by means of invalid reasoning. We can also arrive at a false conclusion by means of valid reasoning - just when our premises are false.

Validity has the technical meaning of 'an argument is valid if the truth of its premises ensures the truth of its conclusions', which does not guarantee that the conclusions of a valid argument are always true, nor that we cannot arrive at false conclusions through a valid argument. All validity requires is that if the premises are true then the conclusions are true. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.Red itself is not the paradigm here. The paradigm is a sample, an example of a red thing, which gives meaning to the word "red". This paradigm may be a physical object, or in the mind. That is Wittgenstein's resolution to the apparent contradiction. "Red" has no meaning unless there is a paradigm to demonstrate red. So "red exists" has no meaning, because "red" has no meaning, unless there is an example of something red, be it a physical object or in the mind. The appearance of contradiction is avoided, because that's all that "red exists" means, that there is such a sample of red, to give the word "red" meaning . — Metaphysician Undercover

Maybe me using 'red' as a paradigm was wrong. The intention I had was to portray red as a facilitator of comparison rather than simply as entities subject to that comparison. As W says in §50, explicating his use of 'paradigm':

It is a paradigm in our language-game; something with which comparison is made. And this

may be an important observation; but it is none the less an observation concerning our language-game—our method of representation.

and refines this function in the parenthetical sentence at the end of §53.

(We do not usually carry out the order "Bring me a red flower" by looking up the colour red in a table of colours and then bringing a flower of the colour that we find in the table; but when it is a question of choosing or mixing a particular shade of red, we do sometimes make use of a sample or table.

but if 'sample' was the correct word to use for 'facilitator of comparison' in both the Paris meter discussion and the discussion of 'red', that's fine.

I'm not doing any of the heavy lifting here, so it's very likely that I'm play too fast and loose with the context of discussion. Regardless, though, I think the point I was making was pretty clear judging from Luke and Street's reactions, I doubt this (possible) error I made disrupts my exegesis too much. -

Question about a basic syllogismI just told him the opposite; to put in the entirety of possiblilities first, and then eliminate regions and populate regions according to the premises. This method has the advantage that the same diagram structure can illustrate the relations between the various syllogistic forms as per wiki link above. I also think it is easier to spot errors. — unenlightened

This is a better way of reasoning with Venn diagrams. However, I think it requires familiarity with how to set them up, which hasn't been demonstrated here.

But here you are just wrong. The usual convention is that universals have no existential import, such that "All Martians curse" does not imply that there are any Martians, but merely denies that there are any that do not curse. Whereas "Some Americans curse" implies that there is at least one American that curses, and specifically and definitely does not mean that there is, or is not, an American that does not curse. In this sense syllogistic meaning departs somewhat from ordinary usage — unenlightened

Absolutely right. I figured that vacuous truths would muddy the waters, considering that having a good understanding of why vacuous truths work requires understanding the duality of existential and universal quantifiers (for all = not for some not, for some = not for all not). This understanding isn't in place here, and I believe the purpose of instruction here is to make Venn diagrams and their connection with formal reasoning intuitive, rather than to provide a fully accurate and nuanced account. -

Question about a basic syllogism

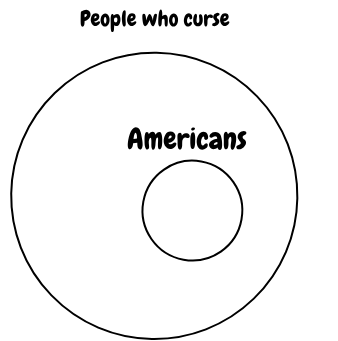

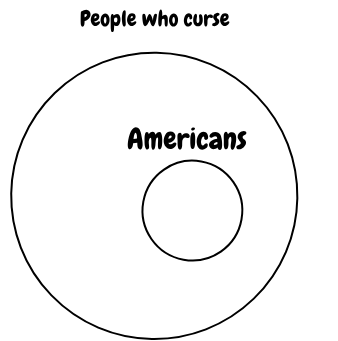

In your first diagram, if all Americans curse, the entire circle of Americans should be inside of the entire circle of cursing people. This is like the logic that 'all hawks are raptors' or 'all pens are writing implements' or 'all humans are mortal'.

If it helps, there's a way of thinking of Venn diagrams in terms of sets - collections of objects. If we have 'all humans are mortal', say, this says that the collection of humans; that's you, me, everyone else; is a sub-collection of mortals; that's you, me, everyone else, everything else that dies.

This 'everything else that dies' means that the circle of 'humans' resides strictly within the circle of 'mortals'.

How this relates to implication and arguments is that when one circle (a smaller one) resides entirely within another (a bigger one), we can say that if something is in the smaller one then it is also in the bigger one. This is entirely equivalent to saying that if something is human then it is mortal.

Applying this to your Americans curse example. The Venn diagram for the assumption that 'All Americans curse' are:

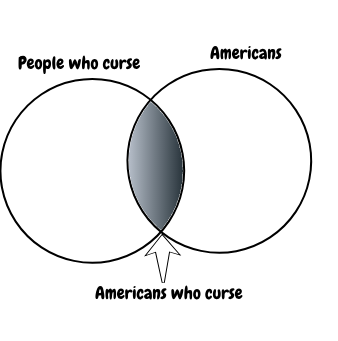

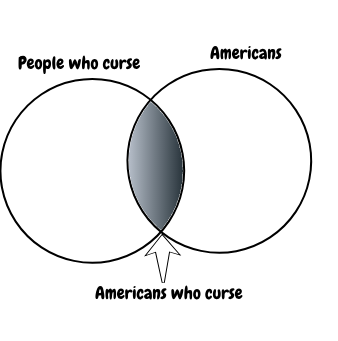

whereas for the assumption that 'some Americans curse' it is:

The translation from 'All Americans Curse' to an 'if-then' statement would be 'If something is an American then it curses', and it works in the way I just described. The next bit has some extra detail, if you feel you understand the points I've made so far, you might get something out of it, otherwise keep trying simple examples.

-------

In the case where 'All Americans curse' it's also true to say 'Some Americans curse'. But 'All Americans curse' is a stronger statement than 'some Americans curse'. In terms of the Venn diagrams, 'some Americans curse' means that the circles for 'people who curse' and 'Americans' overlap a bit, whereas 'All Americans curse' means that the circle for 'Americans' resides entirely within the circle for 'people who curse'. The important difference here is that when there's only a bit of overlap - when we can't say that all Americans curse, but we can say that some Americans curse - this means that there is at least one American who does not curse. There being 'at least one American who does not curse' is equivalent to the circle of 'Americans' not entirely residing within the circle of people who curse - if you've been following along, 'the circle of Americans not entirely residing within the circle of people who curse' is completely consistent with 'the circle of Americans and the circle of people who curse have NO overlap at all', which means 'no Americans curse'; or 'there are no Americans who curse', or 'if someone curses, they are not an American'.

' -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.↪fdrake I think that this reading actually brings to completion a line of thought that Witty himself only half finished in §58, because he got caught up in a different but related 'second' line of thought relating to the 'contradictions'. My feeling is that there are two intertwined lines of thought in §58, one more clear than the other, which is yet another reason it's so confusing. — StreetlightX

There were a couple of things I wanted to add, I'll also take that response from Street as an invitation to spell out explicitly the 'contradiction' referenced in §58.

So, I'm a bit confused by the precise sense in which Witty diagnoses the contradiction; what conceptual machinery does he have going in the background that makes 'contradiction' an appropriate choice of word here? First to spell out the contradiction as I see it.

Witty posits that red is used as a paradigm in most language games in which red plays a role. The existence of red is not the kind of thing that makes sense to ponder or raise when, say, matching tins of paint to colours on a chart or describing someone's hair. This means that 'red exists' and 'red does not exist' play no role in those language games, and thus can be said to be senseless in their native contexts. Wittgenstein leverages this insight to block an inference from a 'game of subtraction' of red exemplars to their supposedly underlying/grounding type of red, or the 'indestructible' redness. This inference is blocked by, as Wittgenstein calls it, a contradiction.

For more detail about how I see the rest of §58 look at this post. Now I'm focussing only on the contradiction which blocks the inference. The inference, as I construed it in the previous post, was:

If we subtract away the things which are red, we are left with the same underlying conception that applied in each instance. Then that underlying conception is the meaning of red, but the use of that underlying conception requires a really existing colour type, red, independent of every red object.

In the antecedent, 'If...instance', red is treated as a paradigm in the language game of colour subtraction. This means that 'red exists' and 'red does not exist' equally do not apply. However, red loses its status as a paradigm in the consequent of the inference because 'red is a really existing colour type'. In the consequent, the requirements of sense are that red is not playing the role of a paradigm, in the antecedent, the requirements of sense are that red is playing the role of a paradigm. In moving antecedent to consequent, we necessarily suppress the requirement that 'red exists' is senseless which is encoded in treating red as a paradigm.

The bit I'm having trouble with is whether we can actually treat the requirement that 'red exists' is senseless as a typical premise in a syllogism. Wittgenstein seems aware that this isn't quite right in how he introduces the logic of the 'contradiction'

Or perhaps better: "Red does not exist" as " 'Red' has no meaning". Only we do not want to say

that that expression says this, but that this is what it would have to be saying if it meant anything.

we have a modality in the presentation here, that we must make the equivalence between 'red does not exist' and 'red has no meaning', conflating existence and having sense as Street focussed on in his exegesis. But that modality - of necessity - seems to operate on something like an a priori register with respect to the language games considered; on the conditions of sense making in the considered language games; so this is really a 'philosophical' move Wittgenstein is making. It's a conceptual link forged with a certain logical (grammatical?) necessity.

So Wittgenstein sees the contradiction as necessarily arising in going from the antecedent to the consequent, it 'comes along with' and 'acts as a guarantor of' the inference, speaking very loosely. Nevertheless, there are ways at 'arriving' at 'red exists' without making this abuse of a logic of sense, at the end Wittgenstein highlights that:

In reality, however, we quite readily say that a particular colour exists; and that is as much as to say that something exists that has that colour. And the first expression is no less accurate than the second; particularly where 'what has the colour' is not a physical object.

so the sense of necessity Wittgenstein looks to be dealing with isn't something that blocks the sense 'red exists' in all contexts, it just blocks it in the sense he was dealing with. A very circumscribed sense of necessity, in contrast to the haphazard forging of necessary conceptual links that he's literally criticising in §58!

It looks to me like there's a lot going on 'under the bonnet' in §58, and we might do well to return to it once we have other examples of Wittgenstein making similar conceptual links.

Related to this, I think anyway, is that there's a real 'screw you philosophy' feel to §58, I think this comes from the two things W. thinks he's established:

(1) That we cannot infer the independent existence of red the colour from its examples without the previously discussed deaf ear for context.

(2) Nevertheless, we absolutely can say the things which were philosophically illegitimate to derive from the considered context. 'Red exists as an independent type' in the philosophical sense derived from the 'subtraction'/destruction exercise? Nah. 'Red exists' from a different point of departure? Sure!

How this resonates with me is that it introduces a certain mutilation of conceptual inferences, and something like a 'relativisation' of the a priori to an a priori for a (family of?) language game(s?) (I'm referencing this 'locally circumscribed' sense of necessity W. seems to be using). The access to the eternal and the true realm of abstraction through philosophical contemplation of essences is not an adequate take on what it means to think philosophically. The inquiry's point of departure; more generally how it interfaces with the contexts and content it uses as grist; matter a lot. So much so in fact that it's easy to wind up in a dead end of malformed questions that aren't a jot relevant to their supposed subject matter.

The last paragraph should be taken with a whole pood of salt. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.Flittering in and out of the discussion is likely to make me miss nuances and make inaccurate analogies, so please treat this post as an attempt to parse §58 into my own views of how stuff works - with my idiosyncratic and externally motivated abstractions - rather than an attempt to accurately reflect the text.

The open question then is what this whole dialectical movement between thing, meaning, and then dismissal/synthesis is meant to show. I think that the point is to show that there is no ‘opposition’ between existence and meaning, and that insisting on the one does not preclude the other: it is both perfectly possible to say that ‘red exists’ - we do it all the time, ‘in reality’ - and that in doing so, we can still talk about our use of the word. — StreetlightX

Reading §58, the first thing that jumps out to me is how the context of W.'s discussion changes over the passage. The first paragraph with scare quotes around it looks to me as a first attempt at covering W's desired ground provisionally, to show what he intends by means of an approximation. This approximation is successively refined and worked out over the course of §58. The shifts in context are what make it difficult, I feel.

"I want to restrict the term 'name* to what cannot occur in

the combination 'X exists'.—Thus one cannot say 'Red exists', because if there were no red it could not be spoken of at all."—Better: If "X exists" is meant simply to say: "X" has a meaning,—then it is not a proposition which treats of X, but a proposition about our use of language, that is, about the use of the word "X". — Wittgenstein

I think we have a reference to bipolarity in the first bit with the scare quotes. We cannot say that red exists in usual contexts involving the use of the word red because it would make no sense to say that it did not exist. 'Exists' and 'not exists' are the two poles, each the negation of the other, which are providing the litmus test of sense here. I think it's similar to the meter stick example. In the meter stick example, we have the Paris meter providing the paradigm of what it means to say that an object is 1 meter long in a language game of measurements. In this example, which does not have a specifically attached context/language game, it seems that 'red exists' and 'red does not exist' analogise to 'the Paris meter is 1 meter long' and 'the Paris meter is not 1 meter long'; red serves as a paradigm by which we represent placeholders which count as red. Counting as red meant in a deflationary sense of simply counting as red in a language game involving colours. So it looks to me as if the first paragraph is scoping over various colour language games, and generalises from these implicitly treated language games that 'red exists' is senseless; an illegitimate move in most language games involving red.

Another way of putting it, the kind of language game in which the statement 'red exists' is a legitimate move is not a typical language game involving red! @Luke highlights that considering the statement 'red exists' introduces an on-the-fly context change to make sense of, we are no longer considering most practical uses of language involving red, we're playing a more abstract game using the same word. Wittgenstein highlights this shift too in the second paragraph, and the 'it looks as if' the second paragraph begins with seems to me to highlight that Wittgenstein's thoughts are covering a variety of language games involving red. So onto the second paragraph:

It looks to us as if we were saying something about the nature of red in saying that the words "Red exists" do not yield a sense. Namely that red does exist 'in its own right'. The same idea—that this is a metaphysical statement about red—finds expression again when we say such a thing as that red is timeless, and perhaps still more strongly in the word "indestructible" — W

Saying something about the nature of red is not something done or doable in typical language games involving it. Playing the move 'red exists' is something we can understand however; there are language games in which it has a sense; but we only give it sense here (illegitimately) through the fungibility of context which accompanies uses of language. What is illegitimate, I think W. thinks, is to situate 'red exists' within typical language games involving red.

It's at this point that §58 really grows its teeth, attempting to destroy the ground of the philosophical transformation that occurs to red when unmoored from language games in which it serves as a paradigm.'examplesExamples where red serves as a paradigm are for the square game, colour ascription, or use as part of a description.

But what we really want is simply to take "Red exists" as the statement: the word "red" has a meaning. Or perhaps better: "Red does not exist" as " 'Red' has no meaning". Only we do not want to say that that expression says this, but that this is what it would have to be saying if it meant anything. — W

What philosophical move does Wittgenstein want to prohibit and why? I think Wittgenstein wants to prohibit the following line of thought:

We see when we look around that things have colours, and one of these colours is red. If we subtract away the things which are red, we are left with the same underlying conception that applied in each instance. That underlying conception is the meaning of red, but the use of that underlying conception requires a really existing colour type, red, independent of every red object. — me with my Platonist type-token distinction hat on

which is a rephrasing of what the interlocutor says in W's §57:

"Something red can be destroyed, but red cannot be destroyed, and that is why the meaning of the word 'red' is independent of the existence of a red thing." — W

How he seeks to prohibit this is to show that the inference 'if we subtract away the things which are red, then we are left with the same underlying conception that applied in each instance' is illegitimate. It is illegitimate because it requires a conflation of red when serving as facilitator of representation (a paradigm) and red when serving more abstractly as a concept. This conflation is specifically undercut by the bipolarity principle: how can we say red can or cannot be destroyed when serving as a paradigm? Simply by forgetting that it is serving as a paradigm in one instance; the 'colour ascription' context inherent in 'subtracting away the red things', in the antecedent of the inference... And no longer treating it as a paradigm in the consequent of the inference. Red 'could not be destroyed' in the first instance because of how red is used in that context, and we arrive at a red type independent of language use precisely through the elimination of exemplars of the paradigm.

It is as if we removed all objects to be measured from the Paris meter stick measuring game, then inferred the a-priori, use independent existence of the meter as a standard. Perhaps we can forget the use of the meter as a standard in some instances of mathematical calculation involving dimensionally consistent lengths, but that calculating language game does not use the meter as a paradigm for/during its moves.

The whole issue deflates when treating red in a deflationary, entirely sortal manner, what red is is what counts as red; what roles red serves in our language games. W. closes the discussion in §58 by showing us contexts in which it does, however, make sense to say 'red exists'. -

Understanding Spinoza Part 2 - How can God have infinite extension?But, HOW can God be considered an extended thing since most philosophical schools deny that God could have a body. And no physical substance means no extension, right? — SapereAude

Spinoza has two notions which are similar to 'property', so when we're saying something 'has' extension you have to be careful whether that 'has' predicates in the sense of Spinoza's attributes or Spinoza's modes. Attributes apply specifically to substances, modes apply to everything else.

A substance 'has' extension in the same sense (roughly) that a triangle has three sides. The structure (having three sides) is a necessary feature of the thing (triangle). In Spinoza's terms, extension is an attribute of substance. As it says in definition (IV):

IV. By attribute, I mean that which the intellect perceives as constituting the essence of substance. — Spinoza

An entity 'has' extension in the same sense (roughly) as a person has a personality which is their own; it's (personality) a contingent feature of the entity (person) shaped by interactions (modifications, conceived through other than itself). As it says in definition (V):

V. By mode, I mean the modifications of substance, or that which exists in, and is conceived through, something other than itself. — Spinoza

So, if entities are extended, substance's extension is the sine qua non of their extension.

So I cannot figure out how Spinoza comes to the conclusion that God has infinite extension.

Then we need to look at why for Spinoza, substance's extension is infinite. Infinity in Spinoza is bound up with the notion of non-limitation. The first time this crops up is in definition (II), but non-limitation is at work 'in absentia' so to speak:

II. A thing is called finite after its kind, when it can be limited by another thing of the same nature; for instance, a body is called finite because we always conceive another greater body. So, also, a thought is limited by another thought, but a body is not limited by thought, nor a thought by body. — Spinoza

Imagine a pie. You cut the pie in two, the amount in each piece is limited by the amount in the whole pie. Thus, the pieces are finite (in extension) after their kind. But also remember that the first line of the definition says '...when it can be limited...', not necessarily just that it is. So the pie pieces are finite after their kind because they were capable of being limited, not because they actually were.

For this division of the pie to make sense, and also for the division to come to exist, there has to be an underlying extension which both pie pieces and the whole pie partake in which can lend reality to the extension of the pie and the pieces; that underlying extension (prior to all pies and pie modification) is the extension of substance. As an attribute (extension itself), not a mere mode (pie piece sizes).

The second time this logic crops up it does so explicitly, in proposition VIII:

PROP. VIII. Every substance is necessarily infinite.

Proof.—There can only be one substance with an identical attribute, and existence follows from its nature (Prop. vii.); its nature, therefore, involves existence, either as finite or infinite. It does not exist as finite, for (by Def. ii.) it would then be limited by something else of the same kind, which would also necessarily exist (Prop. vii.); and there would be two substances with an identical attribute, which is absurd (Prop. v.). It therefore exists as infinite. Q.E.D.

The logic here is a disjunctive syllogism. X is either finite or infinite, can't be finite, so it must be infinite. The reason the finitude of substance fails for Spinoza is that substance itself 'contains' no (de)limitations, there are no properties or entities which cease to be 'active' for substance at any time. If substance had a bounded extension in space (has in the sense of attribute), it would not be infinite firstly because its extension is limited but more importantly because this requires applying any limitation to substance which contradicts the 'infinity' of specific attributes (like extension) set up in definition VI:

VI. By God, I mean a being absolutely infinite—that is, a substance consisting in infinite attributes, of which each expresses eternal and infinite essentiality. — Spinoza

However, we have to remember that substance's infinity isn't an infinity of a specific sort - like infinite extension, but the absence of delimitation tout court (specific sorts would also have a logic of delimitation!). So for a concluding remark, I'll share the mental picture I have of Spinoza's idea of god or substance. Imagine we have an exhaustive list of every possible way of being, every possible way for which something could be and is. Substance is that which has all those properties (attributes) always and forever. Substance is the cosmic light switch which is always on for every way of being, and the light controlled by the switch. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.@Sam26@Luke@John Doe@StreetlightX

I just want to thank you lot for the great discussion/exegesis. I hope you manage to keep it up. -

Willpower - is it an energy thing?The ego here is used in the psychological sense. — Amity

Ego depletion doesn't really require the Freudian notion of the ego to get going. As a phenomenon, all it requires is that people exhibit less self control when they're in states of fatigue, especially when that fatigue is induced by concentration or tasks which otherwise require self control.

I think it's a reasonable idea that's fraught with problems when trying to experimentally verify it. -

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading GroupI finished what I wanted to do in my thread. I'm available for leading Riemann in a week or so, as I've other more important/work related commitments on my brainpower. @StreetlightX, we should coordinate so that a (tentative) timeframe can be put down.

-

Marx's Value TheoryMarx concludes this line of thought on the development of humanity:

The life-process of society, which is based on the process of material production, does not strip off its mystical veil until it is treated as production by freely associated men, and is consciously regulated by them in accordance with a settled plan. This, however, demands for society a certain material ground-work or set of conditions of existence which in their turn are the spontaneous product of a long and painful process of development.

saying that a society which does not have all the above socio-economic-political growing pains will only come out of a similarly painful process of development.

He then concludes the section on commodity fetishism, and Chapter 1, with a discussion of the image of capitalism in economic thought in his time and how that image relates to commodity fetishism. Much of it is minor elaboration and summary.

Political Economy has indeed analysed, however incompletely,[32] value and its magnitude, and has discovered what lies beneath these forms. But it has never once asked the question why labour is represented by the value of its product and labour time by the magnitude of that value.[33] These formulæ, which bear it stamped upon them in unmistakable letters that they belong to a state of society, in which the process of production has the mastery over man, instead of being controlled by him, such formulæ appear to the bourgeois intellect to be as much a self-evident necessity imposed by Nature as productive labour itself. Hence forms of social production that preceded the bourgeois form, are treated by the bourgeoisie in much the same way as the Fathers of the Church treated pre-Christian religions.[34]

The take home message here is that Marx believes it is very common for economists to inappropriately retroject commodities with the social form they have under capitalism into precapitalist modes of production; summarising his analysis of Robinson Crusoe like scenarios.

To what extent some economists are misled by the Fetishism inherent in commodities, or by the objective appearance of the social characteristics of labour, is shown, amongst other ways, by the dull and tedious quarrel over the part played by Nature in the formation of exchange value. Since exchange value is a definite social manner of expressing the amount of labour bestowed upon an object, Nature has no more to do with it, than it has in fixing the course of exchange.

Moreover, Marx believes it is common for economists to believe that exchange value rises out of natural properties of produced goods, rather than out of the relationship of their having utility and only being available through purchase. IE, he thinks that people treat use value and exchange value in an inverted way, use deriving from social custom and exchange deriving from physical property.

The mode of production in which the product takes the form of a commodity, or is produced directly for exchange, is the most general and most embryonic form of bourgeois production. It therefore makes its appearance at an early date in history, though not in the same predominating and characteristic manner as now-a-days. Hence its Fetish character is comparatively easy to be seen through. But when we come to more concrete forms, even this appearance of simplicity vanishes. Whence arose the illusions of the monetary system? To it gold and silver, when serving as money, did not represent a social relation between producers, but were natural objects with strange social properties. And modern economy, which looks down with such disdain on the monetary system, does not its superstition come out as clear as noon-day, whenever it treats of capital? How long is it since economy discarded the physiocratic illusion, that rents grow out of the soil and not out of society?

Marx notes that the value form in capitalism contained its seeds in precapitalist value forms, some of which are analysed. He leaves a question hanging, whether the analysis he's developed so far is really appropriate for the full complexity of observed economic development (spoilers: almost everything here is an oversimplification in some regard).

But not to anticipate, we will content ourselves with yet another example relating to the commodity form. Could commodities themselves speak, they would say: Our use value may be a thing that interests men. It is no part of us as objects. What, however, does belong to us as objects, is our value. Our natural intercourse as commodities proves it. In the eyes of each other we are nothing but exchange values. Now listen how those commodities speak through the mouth of the economist.

“Value” – (i.e., exchange value) “is a property of things, riches” – (i.e., use value) “of man. Value, in this sense, necessarily implies exchanges, riches do not.”[35] “Riches” (use value) “are the attribute of men, value is the attribute of commodities. A man or a community is rich, a pearl or a diamond is valuable...” A pearl or a diamond is valuable as a pearl or a diamond.[36]

From the perspective of commodity-commodity relations, they are mediated by value, so through the 'eyes of the commodity' see only values rather than uses (which are not realised in exchange). From the perspective of the commodity, then, other commodities appear as price stamps alone mediated through exchange, rather than a composite relationship of the market and labour to commodity production and the political structures which facilitate this (like the social division of labour).

So far no chemist has ever discovered exchange value either in a pearl or a diamond. The economic discoverers of this chemical element, who by-the-bye lay special claim to critical acumen, find however that the use value of objects belongs to them independently of their material properties, while their value, on the other hand, forms a part of them as objects. What confirms them in this view, is the peculiar circumstance that the use value of objects is realised without exchange, by means of a direct relation between the objects and man, while, on the other hand, their value is realised only by exchange, that is, by means of a social process. Who fails here to call to mind our good friend, Dogberry, who informs neighbour Seacoal, that, “To be a well-favoured man is the gift of fortune; but reading and writing comes by Nature.”[37]

Marx concludes the section by attempting to show that commodity fetishism invites the inversion of use an exchange as abstractions. Exchange appears natural, use appears incidental, which ties together with the previous theme of inappropriate retrojection of capitalist commodities into pre-capitalist production.

Now I'm at where I said I'd stop. I might return later to continue, or write summaries, highlights and reference more contemporary things. -

Marx's Value TheoryMarx takes a tangent next, relating religious belief to capitalism. Specifically, he diagnoses that religions which have a structural symmetry with the metaphysics of capital he's developed; the forms with a universal equivalent and resultant commodity fetishism; have their styles of belief promoted. Beginning:

The religious world is but the reflex of the real world.

Which is quite a bold assertion, but it is likely that Marx believes it is justified by the preceding stages of argument about commodity fetishism. So we can expect Marx to analogise some 'moving parts' of his brief analysis of religion to his analysis of value. The statement alone, however, characterises religions as reactive to the conditions of life in which they develop - taking an anthropological or descriptive stance towards them rather than a theological one. Marx elaborates:

And for a society based upon the production of commodities, in which the producers in general enter into social relations with one another by treating their products as commodities and values, whereby they reduce their individual private labour to the standard of homogeneous human labour – for such a society, Christianity with its cultus of abstract man, more especially in its bourgeois developments, Protestantism, Deism, &c., is the most fitting form of religion.

which draws the prefigured analogy between concrete labour being a bearer of abstract labour, and money's reifying power towards the social relations underlying its function. To borrow from Discworld cosmology, Marx probably sees Christian God(s) as anthropomorphic personifications of humanity itself. To arrive at a God, strip away all the base and fleshy worldliness of our bodies and wants, and in doing so eviscerate humanity to a ghostly form. Attribute the material and social relations which we value, what finally remains of a human when all their bodily organs and social necessities are removed, to the attitudes and attributes of a God. This is quite similar to the removal of all specificity of work when a product enters exchange; the transition from concrete to abstract labour. To repurpose Hamlet:

What a piece of work is a man! How noble in reason, how infinite in faculty! In form and moving how express and admirable! In action how like an angel, in apprehension how like a god!

we should not be surprised to find Gods who exonerate the good in man, as they are embodiments of that good seen in reverse. It has been said that morality flows from God, more accurately God flows from humanity.

More importantly, though, what this comment emphasises is a materialist view of religion; religions as a social construct with an internal logic that adapts itself to the conditions of life surrounding it. For an example, Franciscan monks still take a vow of poverty, but now that vow of poverty allows computer access - even the monasteries need PR.

Marx continues his elaboration on the theme of the reactivity of religion, drilling down to its core:

In the ancient Asiatic and other ancient modes of production, we find that the conversion of products into commodities, and therefore the conversion of men into producers of commodities, holds a subordinate place, which, however, increases in importance as the primitive communities approach nearer and nearer to their dissolution. Trading nations, properly so called, exist in the ancient world only in its interstices, like the gods of Epicurus in the Intermundia, or like Jews in the pores of Polish society. Those ancient social organisms of production are, as compared with bourgeois society, extremely simple and transparent. But they are founded either on the immature development of man individually, who has not yet severed the umbilical cord that unites him with his fellowmen in a primitive tribal community, or upon direct relations of subjection. They can arise and exist only when the development of the productive power of labour has not risen beyond a low stage, and when, therefore, the social relations within the sphere of material life, between man and man, and between man and Nature, are correspondingly narrow. This narrowness is reflected in the ancient worship of Nature, and in the other elements of the popular religions. The religious reflex of the real world can, in any case, only then finally vanish, when the practical relations of every-day life offer to man none but perfectly intelligible and reasonable relations with regard to his fellowmen and to Nature.

Religion then is a sign of an immature humanity mystified by its relation to nature and its relations with itself. Mysticism fills the spiritual, explanatory and political gaps in the world. The spiritual void between works and grace reflects the material conditions of the working poor and the workless rich, where works diminish in importance relative to grace as wealth increases. The explanatory hole between the worker and the systems they partially constitute but are constrained by engenders a powerless trust and trust in our own powerlessness; the desolation of shared social life manifests in a faith in the interconnection of everything. The absence of political power the worker has relative to all economic life relevant to their welfare manifests in valuations where a person is judged on their ability to lead a happy life rather than a meaningful one. Faith grows in these holes like scar tissue on our body politic, reconnecting essentially what has only been contingently severed. Only when humanity has mastery of itself and accommodates reasonably to nature will we have no wounds for religion to heal. -

Burned out by logic Intro book

I don't think the answers are necessary. You actually get a lot more writing out proofs and checking them for errors systematically yourself. Unless you have a really short time frame for learning all this stuff, it pays to take it slowly. -

Marx's Value TheoryMarx moves on to considering a freely associating group of producers whose production aims to satisfy collective need, and their share of the distribution of goods is proportionate with that need.

Let us now picture to ourselves, by way of change, a community of free individuals, carrying on their work with the means of production in common, in which the labour power of all the different individuals is consciously applied as the combined labour power of the community. All the characteristics of Robinson’s labour are here repeated, but with this difference, that they are social, instead of individual. Everything produced by him was exclusively the result of his own personal labour, and therefore simply an object of use for himself. The total product of our community is a social product. One portion serves as fresh means of production and remains social. But another portion is consumed by the members as means of subsistence. A distribution of this portion amongst them is consequently necessary. The mode of this distribution will vary with the productive organisation of the community, and the degree of historical development attained by the producers. We will assume, but merely for the sake of a parallel with the production of commodities, that the share of each individual producer in the means of subsistence is determined by his labour time. Labour time would, in that case, play a double part. Its apportionment in accordance with a definite social plan maintains the proper proportion between the different kinds of work to be done and the various wants of the community. On the other hand, it also serves as a measure of the portion of the common labour borne by each individual, and of his share in the part of the total product destined for individual consumption. The social relations of the individual producers, with regard both to their labour and to its products, are in this case perfectly simple and intelligible, and that with regard not only to production but also to distribution.

While this is a rather twee picture, it is quite relevant. Freely associating individuals, that is, individuals which choose their work partners and acquaintances, being apportioned produce in relation to how hard they work... Looks a lot like the ideology we heard from free market libertarians. The idea that people choose their workplace and what that entails, and people take part in the coordination of the total social product through purchase, is an extremely distorted conception of working life under capitalism. The distortion arises by assuming individuals as free associators attempting to produce for their needs directly rather than through the medium of value/monetary exchange and commodity production. The division of labour looks more like a spontaneous development of politically independent agents rather than a historically influenced matching of worker competence/availability considerations/requirements to a job; it makes it appear that workers have dominion over their own workplaces and workplace policy, rather than needing to organise independently of their managerial staff to obtain some modicum of influence. Each person as a Robinson Crusoe removes all the relevant social texture that makes capitalism capitalism.

Edit: Just to draw out an implication here: Marx does not see the above quote as a good description of capitalism, by way of contrast the description has: worker control of total production, worker control of association, payment in proportion to need and payment in proportion to effort. By structural symmetry then, Marx sees that the worker under capitalism has limited control of total production, limited control of association, reward in disproportion to need and reward in disproportion to effort. It is as if the economy runs people.

Edit2: Another implication, Marx sees that removing the value abstraction also removes commodity fetishism. People's interactions need to be mediated by the market for commodity fetishism to take hold, and free association does not have this mediation. -

Marx's Value TheoryMarx addresses the 'Robinson Crusoe Economy' here, which has been used as a thought experiment for assessing how value and labour relate. The overall thrust of the argument is (1) to highlight problems in using this thought experiment to analyse capitalist production and exchange relationships and (2) to use commodity fetishism; in the sense of the character of capitalist production being 'hidden in' value; to explain why it's a popular example.

Since Robinson Crusoe’s experiences are a favourite theme with political economists,[30] let us take a look at him on his island. Moderate though he be, yet some few wants he has to satisfy, and must therefore do a little useful work of various sorts, such as making tools and furniture, taming goats, fishing and hunting. Of his prayers and the like we take no account, since they are a source of pleasure to him, and he looks upon them as so much recreation. In spite of the variety of his work, he knows that his labour, whatever its form, is but the activity of one and the same Robinson, and consequently, that it consists of nothing but different modes of human labour. Necessity itself compels him to apportion his time accurately between his different kinds of work. Whether one kind occupies a greater space in his general activity than another, depends on the difficulties, greater or less as the case may be, to be overcome in attaining the useful effect aimed at. This our friend Robinson soon learns by experience, and having rescued a watch, ledger, and pen and ink from the wreck, commences, like a true-born Briton, to keep a set of books. His stock-book contains a list of the objects of utility that belong to him, of the operations necessary for their production; and lastly, of the labour time that definite quantities of those objects have, on an average, cost him. All the relations between Robinson and the objects that form this wealth of his own creation, are here so simple and clear as to be intelligible without exertion, even to Mr. Sedley Taylor. And yet those relations contain all that is essential to the determination of value.

The thing to notice is that Marx highlights that the division of labour works a lot differently in Crusoe's island. Instead of having groups of people producing different things to be put on the market and later bought with currency when they satisfy a need/want, Robinson Crusoe apportions his time directly to satisfy his needs and wants. Keeping a ledger of how long it takes him to do certain things really adds very little to this 'one person economy', as there is no notion of exchange to buttress the formation of capitalist value forms. Moreover, Crusoe is only dependent upon himself for the satisfaction of his wants/needs; this also means that his labour is not social - it does not relate to a grander system of wants and needs over and above the requirements of Mr Crusoe. Nor is it social in the capitalist sense as it is not value productive (profit-motivated).

Let us now transport ourselves from Robinson’s island bathed in light to the European middle ages shrouded in darkness. Here, instead of the independent man, we find everyone dependent, serfs and lords, vassals and suzerains, laymen and clergy. Personal dependence here characterises the social relations of production just as much as it does the other spheres of life organised on the basis of that production. But for the very reason that personal dependence forms the ground-work of society, there is no necessity for labour and its products to assume a fantastic form different from their reality. They take the shape, in the transactions of society, of services in kind and payments in kind. Here the particular and natural form of labour, and not, as in a society based on production of commodities, its general abstract form is the immediate social form of labour. Compulsory labour is just as properly measured by time, as commodity-producing labour; but every serf knows that what he expends in the service of his lord, is a definite quantity of his own personal labour power. The tithe to be rendered to the priest is more matter of fact than his blessing. No matter, then, what we may think of the parts played by the different classes of people themselves in this society, the social relations between individuals in the performance of their labour, appear at all events as their own mutual personal relations, and are not disguised under the shape of social relations between the products of labour.

Marx moves onto a brief characterisation of European middle ages economies. The distinction he draws between this and capitalist ones is that the interdependence of people's labour takes the form of overall production for need satisfaction, including elements of barter without regulating value. This characterises the European middle age economy as an interdependent network of concrete labour and incidental acts of exchange done by human agents unmediated by a well developed exchange system, where money takes a secondary role to labour and has no 'mystical' fetish character. Emphasising the presence of concrete labour without its capitalist dual (abstract labour), Marx continues:

For an example of labour in common or directly associated labour, we have no occasion to go back to that spontaneously developed form which we find on the threshold of the history of all civilised races.[31] We have one close at hand in the patriarchal industries of a peasant family, that produces corn, cattle, yarn, linen, and clothing for home use. These different articles are, as regards the family, so many products of its labour, but as between themselves, they are not commodities. The different kinds of labour, such as tillage, cattle tending, spinning, weaving and making clothes, which result in the various products, are in themselves, and such as they are, direct social functions, because functions of the family, which, just as much as a society based on the production of commodities, possesses a spontaneously developed system of division of labour. The distribution of the work within the family, and the regulation of the labour time of the several members, depend as well upon differences of age and sex as upon natural conditions varying with the seasons. The labour power of each individual, by its very nature, operates in this case merely as a definite portion of the whole labour power of the family, and therefore, the measure of the expenditure of individual labour power by its duration, appears here by its very nature as a social character of their labour.

the social character of labour is indexed to localised social interactions; like family units; and 'abstract labour' in the capitalist sense Marx exhibited earlier is not part of work. As he says, the articles produced are not commodities - not because they do not have use, but because they do not have exchange value and its derivative abstractions. -

Marx's Value TheoryChristmas is busier than I thought it would be.

It's worthwhile to linger here for a bit to gather the various uses Marx is making out of commodity fetishism, and how that relates to the maxim 'the material relations between people become social relations between things'.

Firstly, we have that labourers typically only influence labourers in general through the commodities they produce (or the services they give). In this way, the social division of labour leads to a political division of production. Economic life for the labourer typically will not include economic negotiations between them and labourers in different places of work, this is done by the wage payers rather than the wage workers. So, workers in one workplace typically relate to workers in different workplaces only through the use of workplace services. As a corollary, the political agency of people in determining their own conditions of work and influencing workplaces is diminished relative to their wage payers, whose job it is (partially) to make those negotiations. Labourers stand in relation to value and exchange as producers rather than coordinators. The material relations of people = the sphere of relevant economic events to their lives, the social relations of things - exchanging money for goods and services.

Secondly, we have the 'universal equivalent' - money - acting as a unified medium for the relationships of labourers. Everyone needs access to money to satisfy their wants and needs, and we have access to goods whose prices (values) embody their production - so that the material objects (goods, use values) are made parasitic upon their production for profit (money, exchange values). The logic of the universal equivalent is that it summarises all things relevant to the ascription of price through the value that becomes attached to a product, but as soon as that attachment occurs and the commodity is for sale, the deliberations and political events which gave rise to its price become altogether inaccessible epistemically (without independent effort to produce transparency).

Thirdly, we have the first two parts (previous 2 paragraphs in this post) in tandem casting shadows on intellectual analysis of capitalism. From the first part; all the political and historical specificity gets drained out of commodity production, they become numbers related to other numbers as far as the economy is concerned. Every externality, like starvation, freezing to death, shelter, is 'external' to the conceptualisation of the market, and the social costs become addressable only through coordinated patterns of investment; a more extreme version of this error is treating capitalism itself as a necessary material/natural thing rather than a contingent/historical social organisation. From the second part; the relations between people that give rise to prices are secreted away within the commodity. This can introduce two linked errors, one is that it is easy to make the conceptual leap from the materiality of a commodity (its use value; its capacities for desire satisfaction) directly to its prices (through calculations of supply and demand), without the analysis of where value (the capacity to be bought and sold) comes from conceptually and historically. Secondly, the withdrawal of the world which influenced the ascription of a price to its commodity is highly suggestive of the removal of political agency from forming prices. If we start from social relations between things, it will appear all the economy's constitutive social relations are relations between things (insofar as we're talking about the economy). So we assume too much unanalysed context, posing our inquiry badly. Marx discusses these errors in terms of Robinson Crusoe later in the chapter.

The material relations of people - acts of valuation and production which give commodities their price, physical characteristics and social roles - become social relations between things - mediated by valuation, or directed towards price/profit production.

The categories of bourgeois economy consist of such like forms. They are forms of thought expressing with social validity the conditions and relations of a definite, historically determined mode of production, viz., the production of commodities. The whole mystery of commodities, all the magic and necromancy that surrounds the products of labour as long as they take the form of commodities, vanishes therefore, so soon as we come to other forms of production.

Marx is emphasising the historical specificity of capitalism, rather than treating it as a necessary social formation. Other than that, this is a preparatory remark whose themes I broadly covered above. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.

Considering we both agree when talking about the context of the discussion in the PI we should table the discussion for later I imagine. We could probably go back and forth about it for a long time, which would just derail this marvellous thread. -

Marx's Value Theory

I'm surprised you've continued reading the section on fetishism if my explanations are that bad! -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.

I read that post and agreed with it.

the predication or its negation or complement serve no purpose in a genuine language-game, the predication and its negation or complement are judged to have violated a rule of philosophical grammar

I agree that it makes no sense for C1 comparisons. What I've been trying to show is that there are language games in which it makes sense to say that the Paris meter stick is 1 meter long! -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.

I see being unable to say that a meter stick is a meter long, nor that it's not a meter long, based upon a hypothetical situation that otherwise makes sense, is a paradox. Perhaps it's better to say that it's extremely counter intuitive.

I don't think Wittgenstein really believes that we can't say a meter stick is 1 meter long, I think he's using the example to illustrate what can happen when we pay insufficient attention to the prerequisites for our language use; even maybe how asking a question in the wrong context; or a poorly formulated question; leads to batshit insanity. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.

I don't imagine there's a way to think about angles without requiring thinking about relative positions (differences of positions) of (probably the same) shapes in the plane, no. Whenever you draw an angle there's a starting point and an end point, or a comparison of objects in which one serves as a base.

Though, you can codify rotations as distinct entities, they can be represented as matrices (which are transformations of points). I imagine this step of abstraction is similar to the one going from '1 meter' to 'length 1' (like C1 to C2 in my previous post). In this way you can forget the 'starting point' by making it an arbitrary application of rotation. IE rotating something 90 degrees is still the same rotation even if you do it on a horizontal or vertical line, even though it does not produce the same shape. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.

That might be the crux of it. It's possible to understand angles as transformed ratios of lengths; but we could similarly understand lengths as transformed times (like lightyears). I don't know if it makes sense to see angles being derived from of lengths - we'd still have the ability to quantify rotation even without triangles. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.

Just in case this breaks your mind as much as it breaks mine in this context, angles are actually dimensionless quantities - even though we can subdivide a rotation into regular parts arbitrarily, all of those parts remain proportional to radians. Which are dimensionless. That they're dimensionless is required by trigonometry; if you try to do trigonometry with degrees or what have you a conversion to radians is implicitly done in order to allow you to take sines and cosines and so on, otherwise doing something like sin(1 meter) makes the quantity dimensionally inconsistent (sine( 1 meter) = 1 m + (1/3)m^3 ...).

So it appears there are standardisations which don't come along with unit ascriptions, too. -

Marx's Value TheoryMarx continues on this theme of the reflexivity of the market (more precisely the reflexivity of value relations) and attempts to tease out how this reflexivity annihilates the political and historical character of our economic relations. A typical 'moment' in economic life is an encounter with a commodity (even if it's exchanging one for money), and this renders the interaction of agents which produced that commodity opaque. Rather, then, the capacity for having a value gets aligned with market fluctuations; and the relation of supply and demand of pre-established commodities get equated with its monetary expression.

Man’s reflections on the forms of social life, and consequently, also, his scientific analysis of those forms, take a course directly opposite to that of their actual historical development. He begins, post festum (after the fact), with the results of the process of development ready to hand before him. The characters that stamp products as commodities, and whose establishment is a necessary preliminary to the circulation of commodities, have already acquired the stability of natural, self-understood forms of social life, before man seeks to decipher, not their historical character, for in his eyes they are immutable, but their meaning.

As CEO Nwabudike Morgan from Alpha Centauri puts it (from the bourgeoise immutable self regulating system perspective):

Our first challenge is to create an entire economic infrastructure, from top to bottom, out of whole cloth. No gradual evolution from previous economic systems is possible, because there is no previous economic system. Each interdependent piece must be materialized simultaneously and in perfect working order; otherwise the system will crash out before it ever gets off the ground.

Now, Marx begins to transition from discussing SNLT as a mediating feature of value to phrasing things in terms of money itself; a physical expression of value.

Consequently it was the analysis of the prices of commodities that alone led to the determination of the magnitude of value, and it was the common expression of all commodities in money that alone led to the establishment of their characters as values. It is, however, just this ultimate money form of the world of commodities that actually conceals, instead of disclosing, the social character of private labour, and the social relations between the individual producers. When I state that coats or boots stand in a relation to linen, because it is the universal incarnation of abstract human labour, the absurdity of the statement is self-evident. Nevertheless, when the producers of coats and boots compare those articles with linen, or, what is the same thing, with gold or silver, as the universal equivalent, they express the relation between their own private labour and the collective labour of society in the same absurd form.

It is the actual use of money as a universal equivalent which sets up this cyclical/reflexive annihilation of politics and agency from the market. So long as money works as it does we will end up with commodity fetishism; we end up entering the social relations we have with the producers of our needed goods solely through their resultant products.

The absurdity Marx notes here is that commodities really do behave in this fetishised manner; the price of a commodity is simultaneously derived from the aggregate of labour conditions but hides those conditions by coalescing them in a priced object. It is as if 'the kidney' was an organ of the body, or 'the animal' walked among animals. In using money we are influenced by the global conditions of production, the whole world is in every commodity, but precisely because of that we cannot see it. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.

I'm viewing my attempt to neuter the paradox from as beginning from noticing that it makes good sense to say that a meter is 1 meter long from a certain perspective. If we look in the game of 'unit standardisations of length', we can find yards and meters and lightyears and so on, if we look at the conversion rates of these we'll always find that they're in direct proportion with each other, and each unit is in direct proportion with itself with proportionality constant 1.

Once we've set the stage for the units of a dimension, we can largely forget that the units are there. 3 of a unit is always more than 2 of a unit and so on. The specificity of the meter doesn't actually matter for length comparisons, it's rather a preparation for length comparisons which facilitates those length comparisons through the ascription of numerical magnitudes.

The comparison of numerical magnitudes itself is something that can occur independent of the ascription of any scale. So we take something where a scale is implicit (Wittgenstein's measuring game) and then destroy that implicit dependence through a seemingly innocuous question - the question actually invites us to violate the established rules in a subtle way. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.Are you saying that 'token length representations' are abstract units of measurement? Therefore, C2 comparisons are not made relative to the metre stick, but to the metre unit? — Luke

Are you saying that C2 comparisons involve the use of the metre unit, and so here comparisons can be made between the metre unit and the metre stick? — Luke

I think so Luke, hopefully all my extra words helped. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.What is "a comparison in sense C1"? What type of comparison is being made in the C1 sense if it is not a comparison of length/extension? — Luke

I'll try and make it mathematically precise.

By a C1 comparison I meant specifically 'comparing something with the meter stick', so it is a length comparison with the meter stick and only with the meter stick. I was thinking of it like placing something beside a meter stick in order to measure using it, this is one sense in which the meter stick can be used to measure. The way we'd use it to measure wood to be cut and so on.

Looking at the logic of the thing, C1 comparisons take the form of a binary relation M, which looks like xM(meter stick), where x is anything which can be measured except the meter stick (by construction). If we were then asked 'how does (meter stick)M(meter stick) function?', we can't say as a C1 comparison since x is now also the meter stick. The domain of x is all objects (stuff we'd measure IRL) except the meter stick. This means the meter stick cannot be used to establish its own length through C1 comparisons.

A broader sense of length comparison, C2 in my post, takes the form of a binary relation N where we have xNy where x and y are possibly the same. Comparing the length of two items tout court. The domain of x and y are all lengths. The picture I have in my head here are comparisons of magnitudes which represent distances, as if comparing the distance from 0->1 and 1>2 on the number line. Notice that this comparison doesn't need units to make sense.

C2 is broader insofar as it allows length->length comparisons and there is no privileged object which must occur exactly once in every comparison (like the meter stick in C1).

We can do these comparisons without actually associating numbers with the various lengths, notice that in order to set up the meter stick as a standardisation of length we have to be able to say that it is exactly 1 of itself long; this is because all objects and their lengths, then, are a multiple of the meter. So when we 'bring the meter stick to measure itself', we're comparing lengths irrespective of the standardisation (in the sense that we can forget the standardisation is there as it only sets the stage/scales the axes of the space of comparison), when we compare something in sense C1 it will always be done with respect to the meter stick.

Also notice that the ability to say 'the meter is 1 of itself long' is actually a little modification of the previous two senses, insofar as we have established the meter as a standardisation of length-length comparisons as well as object-object comparisons. This means that the meter plays the role of a dimension in length-length (C2) comparisons and the role of a... measuring stick... in C1.

The confusion here, then, is rooted in substituting the meter as a unit of length (dimension) into a comparison which only makes sense (by construction) while using the meter stick as a measuring object. -

Marx's Value TheoryThere are two notes in the next paragraph, the first analyses the relationship of socially necessary labour time (SNLT) to commodity fetishism, the second is an update of the concept of SNLT in the light of a (slightly) more realistic depiction of exchange.

What, first of all, practically concerns producers when they make an exchange, is the question, how much of some other product they get for their own? In what proportions the products are exchangeable? When these proportions have, by custom, attained a certain stability, they appear to result from the nature of the products, so that, for instance, one ton of iron and two ounces of gold appear as naturally to be of equal value as a pound of gold and a pound of iron in spite of their different physical and chemical qualities appear to be of equal weight. The character of having value, when once impressed upon products, obtains fixity only by reason of their acting and re-acting upon each other as quantities of value. These quantities vary continually, independently of the will, foresight and action of the producers. To them, their own social action takes the form of the action of objects, which rule the producers instead of being ruled by them. It requires a fully developed production of commodities before, from accumulated experience alone, the scientific conviction springs up, that all the different kinds of private labour, which are carried on independently of each other, and yet as spontaneously developed branches of the social division of labour, are continually being reduced to the quantitative proportions in which society requires them. And why? Because, in the midst of all the accidental and ever fluctuating exchange relations between the products, the labour time socially necessary for their production forcibly asserts itself like an over-riding law of Nature. The law of gravity thus asserts itself when a house falls about our ears.[29] The determination of the magnitude of value by labour time is therefore a secret, hidden under the apparent fluctuations in the relative values of commodities. Its discovery, while removing all appearance of mere accidentality from the determination of the magnitude of the values of products, yet in no way alters the mode in which that determination takes place.

The first part situates value in the context of exchange, aiming at exhibiting how value clings to commodities so tightly it has been interpreted as a material innate/internal property rather than a socially constructed external/emergent one. The mechanism which does this must 'fix' values relative to each other in a total fashion, so that upon encountering an arbitrary good in the act of exchange we treat it as if its value is an innate property of the good rather than in terms of its social construction.

The idea here is that value determinations must act upon each other in a good-good fashion, internalising commodity fetishism as a procedural component of capitalist production. What is required is an account of how agent-agent relations of politically mediated producers take on the character of good-good relations of market values. In other words, values come to relate to each other as magnitudes over and above their structure of abstract labour; material relations of people become social relations between things.

What sets the ball rolling in the account are aggregate properties of labour fixing SNLT, but this is only an initial impetus of value dynamics in the market - the market in reality is reflexive, it perpetually reacts to itself and not just the structure of labour which underpins it...

The character of having value, when once impressed upon products, obtains fixity only by reason of their acting and re-acting upon each other as quantities of value.

which changes the account of socially necessary labour times determinately fixing prices;

Because, in the midst of all the accidental and ever fluctuating exchange relations between the products, the labour time socially necessary for their production forcibly asserts itself like an over-riding law of Nature.