-

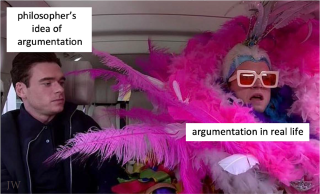

Are insults legitimate debate tactics?I maintain the distinction between rhetorical and rational is taste. Not truth.

-

Not knowing what it’s like to be something else

This is really not true at all even though psychology seems cogent on a superficial level. Reality dictates the subjective consensus that aggregates over time. For easy things like physics this took a mere 2,000 years. Apparently a successful and complete understanding of mind will yet take more trial runs..Thoughts, sensations (consciousness) are areas we've reached consensus on — TheMadFool

Edit: Just to point out I was originally the questioner. I wasn't planing to defend realism. -

Believing versus wanting to believeAn aside. There is currently little reason to think psychological classification is reliable. Replication crisis.

Edit: Excepting cognitive psychology, probably. -

Not knowing what it’s like to be something elseI ask since your subjective-objective struggle can be solved in reference to a third element if you are looking for an explanation that is relevant to multiple people. Let's call it the Reality Theory.

-

Not knowing what it’s like to be something else

Are you talking about reality?how is it that we can agree on anything at all? — TheMadFool -

Believing versus wanting to believe

Energistic-materal-informatic. Plato can't be eliminated.it is assumed that the Universe is essentially energetic-material — Wayfarer -

Not knowing what it’s like to be something else

Oh..the more absurd I can make materialism the better I feel because it's a horrible belief system. — RogueAI -

Are insults legitimate debate tactics?It's not a usual classification. One wonders how the concept of an insult might be defined for purposes of logic. Bonevac 1990 may be of assistance, though he leaves the question unanswered. I take insults as part of pragmatics. I believe it's convenient to reduce them to speech acts.

-

Not knowing what it’s like to be something elseOh, don't worry. It's defined in my list of acceptable arguments.

-

Not knowing what it’s like to be something elseIt's a hint that you're taking a 'so what' position.

-

what do you know?

It's a wonder how we survived this long.The human intellect is a paradox without equal. — synthesis -

Not knowing what it’s like to be something else

Video games.such a description, however complete, will leave out the subjective essence of the experience – how it is from the point of view of its subject — without which it would not be a conscious experience at all -

Are insults legitimate debate tactics?The abusive type of ad hominem argument can be defined in terms of the concept of insult. Personal integrity, moral character, psychological health, or intellectual ability are classic examples.

I'm wondering how insults that are anything less than this can be taken seriously. -

Are insults legitimate debate tactics?Relax. I'm pretty sure anyone who has graduated preschool knows that insults are pointless.

-

Are insults legitimate debate tactics?If they're effective, they're legitimate. Usually they are irrelevant but ultimately it's a matter of taste.

-

Is it possible to be indifferent (Stoic) to the idea of modernity?Assuming these terms denote real things that actually exist and that we should care about?

-

Formless sublime and negative representationIf Kant's idea of the formless sublime is a "viscous contingency of empirical phenomena" (which I interpret as a transcendental real that lacks ultimate logical foundation) and negative representation is the 'raw' noumena/substance/dedomena that is represented by positive data/theories/schema, then they are analogous but not identical.

If they were the same thing they would have the same terms. That difference lies in the context of a third element which is missing from your question. -

what do you know?There is in principle an infinite number of equivalent hypothesis that can justify the same phenomenon.

-

Relativism does not, can not, or must not obtain? Good luck.

-

Relativism does not, can not, or must not obtain? Good luck.That materialism should explain consciousness.

-

Relativism does not, can not, or must not obtain? Good luck.Hypothetically, if it's unfair to say a thermostat in an activated and autonomous state is really analogous to an organism in a vital and conscious state, then by what reason are either vitality or consciousness not 'merely verbal' conceptual expressions of situated human exceptionalism?

-

Relativism does not, can not, or must not obtain? Good luck.

If that's required then I have no particular problem with jettisoning consciousness.Materialism has not explained consciousness. — RogueAI -

Relativism does not, can not, or must not obtain? Good luck."[Possible/necessary] worlds contain [no possible/necessary] matter causing mind". To my mind a thesis based on a negation can prove anything. So let's say you are right. What has changed?

-

Relativism does not, can not, or must not obtain? Good luck.I'm not sure how a negative premise obtains to a positive conclusion.

-

Relativism does not, can not, or must not obtain? Good luck.

Is it a=~x or a=x, then?Some [consciousness/mind] is [exist]. a=x. All [conceivability/thing] is [exist]. b=x. Some [causation/connection] is [matter] is [~exist] and some [causation/connection] is [consciousness/mind] is [~exist]. c=y=~x+c=a=~x.

-

Relativism does not, can not, or must not obtain? Good luck.Logic supplement 3:

Credit to J Wagemans of the grandly-named "Periodic Table of Arguments". A modified version follows:

1. Unit: subject(a,b,c..) and predicate(x,y,z..)

Basic units are taken to be the linguistic subject and predicate of a sentence. The subject is what the sentence is about. The predicate is everything else that is about the subject of the sentence. In the sentence, "the subject is what the sentence is about", the subject is underlined, and the predicate isn't. Another example. "You are browsing thephilosophyforum.com." One last example. "Any x subject does, can, or must, have y status relative to z system of y2 qualities". Computationally, this framework can admit strings of infinite length.

Sentence = Subject + Predicate

2. 'Id-op': 'is'(=) [or "do","can","will"(=)]

Next we define our operation of identity. At the formal level, this is just 'is'. Unfortunately natural language is multivalued and 'is' has many specific definitions. This is unhelpful. But as mentioned in my first post, discourse can be divided into descriptive, evaluative, and prescriptive claims in which people attribute a level of factivity to their claims which is supposed to carry their rhetorical force. Accordingly:

substance: attitude / reference / cognate

In reality there are a limitless number of verbs that my be appropriated for formal use.Is1: 'Descriptive' / Fact / "Do" Is2: 'Evaluative' / Value / "Can" Is3: 'Prescriptive' / Method / "Must"

Determining attitude is obviously a subjective matter of interpretation that will relate to a personalized ontology. There is no real solution for 'correctly' pinning the correct attitude to the respective sentence. Intuition is involved, and this can be especially true when meaning shifts to what has not been said, as with speech acts, messages-by-omission, and whatever other interactive nuance that is partially obscured by the 'code of discourse'. My suggestion -- if in doubt, assume evaluation.

3. 'Prop': subject(a,b,c..) and 'is' and predicate(x,y,z..)

A proposition is a declarative sentence that can be true or false because it contains an 'is' with the following form:

Proposition = 'a is x'

As I would like propositions to become a universal unit of discourse I will define them no further, other than that they must be true or false. A proposition that can bear no value is a sentence, not a proposition.

4. 'Di-op': 'because'(<),'therefore'(>) [or 'if-then'(>)]

The operation of direction indicates the causal, consequential, or relative direction of two propositions adjoined by a 'because' or similar cognate. 'Direction' is my nonstandard term that is just a general logical entailment as dictated by the grammar. Metaphysically, the direction always points away from the most original or prior epistemic source in the formula (or 'formulate').

Here is the definition of the classical conditional, 'therefore':

p q p>q t t t t f f f t t f f t

Which we can use to define a 'because':

p q p<q t t t f t f t f t f f t

We can define any operator we please by using a truth table to define the logical properties of the informative throughput. Tables like these define the basis of logical systems. If their functions are sufficiently complicated, and their definitions sufficiently well-defined, objects like these can constitute the basis of abstract machines.

5. 'Arg': proposition(p,q,r..) and 'because'(<) and proposition(p,q,r..)

Here are two generic forms of argument:

Argument = 'a is x' because 'a / x is b / y' Argument = if 'a is x' then 'a / x is b / y'

Once we identify the two component propositions of the argument we're trying to analyze, whatever terms they have in common is the rhetorical action that links them and creates the force of the argument. By squaring and comparing the components we arrive at the following, where p means 'same proposition', p~= means 'different proposition', s= means 'same subject', and s~= means 'different subject':

s= s~= p= Be1 Be2 p~= Be3 Be4

These are traditionally valid arguments:

Be2 in which two subjects are linked to a single predicate. a=x<a=y. ('Placing').

Be3 in which two predicates are linked to a single subject. a=x<b=x. ('Classing').

These are traditionally invalid arguments:

Be1 in which propositions are linked to themselves or virtually equivalent propositions. a=x<a=x.

Be4 in which propositions have no obvious link. a=x<b=y.

Although we can make them valid with:

Be5 in which propositions are linked to themselves or virtually equivalent propositions but are also linked to 'is true'. a=x<a=x=y. ('Sensing').

Be6 in which propositions have no obvious link but are each also linked to 'is true'. a=x=z<b=y=z. ('Fielding').

Hence:

form: formula / formulate / cognate

Be5: 'a=x<a=x=y' / If subject1 is predicate1 then subject1 is predicate1 (is predicate3) / "Sense" Be2: 'a=x<a=y' / If subject1 is predicate1 then subject1 is predicate2 / "Place" Be3: 'a=x<b=x' / If subject1 is predicate1 then subject2 is predicate1 / "Class" Be6: 'a=x=z<b=y=z' / If subject1 is predicate1 (is predicate3) then subject2 is predicate2 (is predicate3) / "Field"

Again, in all of these arguments, "(is predicate3)" stands for "is true", and 'true' can be any arbitrary value.

6. List of sample arguments

In Wagemans' original framework, a list of prototypal arguments is given as follows:

A majore (greater to lesser) A minore (lesser to greater) Ad baculum (force) Ad carotam (coax) Ad hominem Ad populum Axiologic argument (value) Case to case Deontic argument (duty) Ethotic argument (personal credibility) From analogy From authority From beauty From cause From character From commitment From comparison From consistency From correlation From criterion (ie. metalinguistic eg. definitions) From disjunctives From effect From emotion From evaluation From example From genus From opposites From parallel From sign From similarity From standard From tradition From utility Petitio principii (circularity) Pragmatic argument (convenience-practicality).

How these arguments have been chosen and why they have their factive properties is not explained. Originally they're given a more structured form, where individual propositions have individual factivities. Here they're presented in a more leniant, linear form. The difference is that in my framework, whole sentences are given a factivity in order to facilitate greater interpretive flexibility.

7. Args by validity/form:

So then, a small miracle happens and then arguments can be ranked according to distinct criteria as pertaining to subject-predicate relations:

- Be5 a is x because a is x is y: authority,character,populum / utility,beauty / baculum,carotam / character,ethotic,hominem / emotion.

- Be2 a is x because a is y: cause,correlation,effect,sign / criterion / axiology,standard / pragmatic / deontic,evaluation.

- Be3 a is x because b is x: case,example,genus,similarity / analogy,majore,minore / parallel / comparison.

- Be6 a is x because b is y: consistency / disjunctives,principii,opposites / tradition.

8. Args by identity/substance:

Or graded according to the more indistinct and personal criteria mentioned at the start:

- Pure fact: cause,correlation,effect,sign / case,example,genus,similarity.

- Mixed fact: authority,commitment,populum / criterion / parallel / consistency.

- Pure value: / beauty,utility / axiologic,standard / analogy,majore,minore / disjunctives,principii,oppositions.

- Mixed value: authority,baculum,carotam,character,commitment,ethotic,hominem,populum / evaluation,deontic.

- Pure method: emotion / comparison.

- Mixed method: baculum,carotam,character,ethotic,hominem / deontic,evaluation / parallel / consistency.

It's possible to conjecture that the game of factivity ends when a disputant successfully changes the acceptability of their thesis using a sequence of dialectical moves in which a value is transformed, ultimately via a chain of analogies that may take minutes or decades, into an accepted fact or into an accepted method. Whatever evidence is available to a disputant will not in itself persuade without an explanatory logos relating the object of dispute to the situation of dispute. However, any given situation is a dynamic object that is constantly undergoing change, meaning that, as I mentioned, any given logical endeavor is also a logistical endeavor.

Analysis of individual arguments and why they have their factive properties is something that is possible, though I will leave this aside as there is enough literature on the topic. Presumably, all that remains is a list of universal objects along with their representative factivites that settles the ontological details and fixes the objective criteria about which an argument is supposed to be about.

:) -

Relativism does not, can not, or must not obtain? Good luck.Logic supplement 2:

In my last supplement I concluded a primitive, polysemic logic may be identified. However, locating and fixing meaning comes with logistical in additional to logical challenges that are demonstrated by a sufficiently long history of anything.

The link between logic and (good) reasoning properly dates from the Enlightenment as a relatively recent invention of philosophy. Prior to this, logic was a tool of argumentation for use in ordinary disputation in which logical ('logical') premises entail logical conclusions within a practical framework of common acceptability, otherwise known as Ancient Greek dialectic. Various logos, or accounts, were acceptable, and sorting through fallacious logos was roughly the (usually indirect, doxological) business of some division of the polis (or the philosopher if you're Socrates). The prior analytics, known to be the venerable home of syllogistic logic, is filled with dialectical vocabulary and references to debating practices. Aristotle's other works detail the basis of rhetorics and stylistics. This is quite a departure from the modern meaning of logic as a definite kind of quantified reasoning.

By the middle ages the scholastic fever dream and the schoolmaster method coincided with the spread of universities in which dialectic was the primary teaching method. With the universities established, the culture absorbed these insights until the Renaissance, where certain authors started to deplore its perceived lack of applicability. Syllogistic was gradually deemed an artificial type of exposition that was useless for people looking to speak 'naturally' and only "expresses to others what one already knows to be true". The scholastic logic's theory of syllogistic is a logic of justification, not of discovery. And so the notion of logic was due for another refurbishment.

The early modern period came to see logic in terms of mental facilities of the mind that emphasized the role of novel individual discovery. Supposedly this kind of logic was about uncovering the truth as captured by certain influential publications of the time, ie. Port Royal (subtitle: the Art of Thinking). This trend started in Descartes and culminated in Kant, who interpreted the Aristotelian categories as pertaining to the structure of reasoning, a view that remained pervasive for the next two centuries. By selectively absorbing notions like category, form, and judgement, he put them to new use in describing the conditions for perception and thought. 'Judgement' in English originally concerned legal diagnosis inherited from Old French, but after Kant, judgement now also concerns the inner mental activities of the solitary thinking subject.

By the 20th century this broadly Kantian background provided the basis on which new traditions in psychology analyzed reasoning. Although it was known that participant performances often deviated wildly from the normative responses as defined by the cannons of deductive logic, this was insufficient to overturn the popular link between logic and reasoning, and early findings speculated abstract rules of thought which were supposed to be demonstrated by stages of psychological development, as per Piaget (and significantly via Inhelder, one of his collaborators). However, the picture of human reasoning as proceeding by schematic substitution of different contents has been seriously challenged by experiments suggesting that people don't really reason on the basis of logical rules. At the very least, classical logic is "not at all" an adequate descriptive model for human reasoning.

If humans have normative standards by which they reason, their discovery is still a future prospect. -

Was Nietzsche right about this?

I don't know. But people have been predicting the end of the world since it began.Was Nietzsche correct that the ‘death of God’ would usher in a time of meaninglessness and bloodshed? — Tom Storm -

Relativism does not, can not, or must not obtain? Good luck.

For what it's worth, 'proposition' is my preferred neutral unit. Information is too well-defined.I'd like to find a more "neutral" term, but that's just me. — Manuel

Given systematic conflict is part of my thesis, I'd say that's expected. My analysis doesn't typically concern individuals, though. Especially not alive ones. XDHaack and Chomsky disagree. — Manuel -

Relativism does not, can not, or must not obtain? Good luck.

Feyerabend.Who would be an example of such a philosopher, generally speaking? — Manuel

Who disagrees with the proposition that all information is lossy, or with Feyerabend's anti-realism? If the first, 'information' has an empirical component, so I expect that argument would need to be more substantial than an armchair conclusion. If the second, I don't know. :)Stated like that, who would be an "opponent" or a person who disagrees with this? — Manuel -

Relativism does not, can not, or must not obtain? Good luck.

I think I can safely say 'true' ultimately reduces to a single value (pick any adjective you please) that is open to interpretation but is also sufficient for rational thinking and necessary for realistic application to other rational agents involved in the system in which such a value plays a role in a relevant, probable, utility-bearing sense. What that means more exactly is a matter for ethics.Is that your point, that there are many ways to reach truth or that there are many truths? — Manuel

For me relativism is prior to everything except metaphilosophy. It can treat of everything except how or why we should do philosophy. Our biases here are accidental and, probably, ultimately untreatable. According to my relativistic logos (if we must call it something), everything that exists exits according to some further fact that is usually the relata of some element in a epistemic or metaphysical (or ethical (or whatever)) system -- relativism has a metaontological scope in which pure relativism just defaults to convention. Not very exciting. My metaphilosophy -- my metaphilosophical orientation -- is supposed to be empiricist and positivist. If I'm in an idealistic mood, that's my preferred framing for relativism.

I take postmodernism to be massively misunderstood. For one thing Lyotard, the only one that to my mind embraced the postmodern label, merely defined it as an incredulity towards big stories, grands récits, which eventually developed into an extreme cultural relativism in which the terminal conclusion is seen in Derrida, who basically took the insights of Wittgenstein and the structuralists to show the issues with fixing definitions and the way our thinking is massively shaped by environmental, rather than essential, factors. Rorty was a former positivist and I take his main work to be a mystical thesis who is only coincidentally a postmodernist. To the agnosticism of the French postmodernists, I imagine Rorty's 'nature' simply unmasks to 'God' -- je pense donc je suis Nature.

My point has postmodern sympathies and is captured by the notion of explication. If we must formalize a concept, then the theoretical utility of the concept’s formal correlate must often be traded off against the actual degree of match with the informal target concept. The abstract virtue of simplicity, such as its capacity for further theoretical integration, (almost always) comes at the expense of being a less faithful codification of the informal concept. Or in other words, processing information via any logical or mathematical code inevitably generates a variable amount of 'noise' that would have been essential to the flawless transmission of the original piece of reality that it was intending to meaningfully capture. -

Relativism does not, can not, or must not obtain? Good luck.Sorry if that seemed cryptic. I accept domain-specific ontologies and it's usually easier if they contain the objects listed there -- properties, events, etc. If the analytic ontology can be made universal, so much the better.

-

Relativism does not, can not, or must not obtain? Good luck.Logic supplement:

Many find it natural to assume that of all the philosophical disciplines, logic has the greatest claim to objective truth. Unfortunately it becomes hard to see what objectivity has to do with truth when numerous truthful applications of logic are objectively equivalent. Both von Neumann-Bernays-Gödel set theory (NBG) and Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory with the axiom of choice (ZFC) are equally suitable for mathematical use, and there seems to be no good reason to decide which is best if we assume matters of taste do not apply. Contrary to this attitude is the logical monist and the One True Logic approach, in which one of these results must be false, or one of these models must be invalid. Furthermore, there are numerous different logics, notably exemplified by the classical and intuitionistic approaches to logic, both of which are mutually translative, though they start with different axioms of assumption, of which are yet more components or mechanisms of another formalizable system -- systems ultimately traceable to cognitive conveniences. Even the meanings of 'consequence' and 'validity', which are central to logic, are subject to interpretation. The implications of this are substantial.

I understand the primitive version of modality holds that x is a logical consequence of a set of truthmakers y1,y2..y0 as long as it's impossible for y1,y2..y0 to be true while x is false. The stricter (preferable) Tarskian version holds that x is a logical consequence of y1,y2..y0 as long as x is true under all true interpretations of the non-logical vocabulary of y1,y2..y0. Any definition, even the most natural and supposedly ineffable definition, will show arbitrary features to a greater or lesser degree. Apparently, the proof-theoretic (first) and model-theoretic (second) conceptions are a polysemic expression of intuitive consequence. Accurate formal theories presumably depict different aspects of such a primitive understanding of consequence but their deeper details are (yet) interpretive. A hybrid definition could be that x is a logical consequence of y1,y2..y0 as long as there is a gapless and primitively legitimate mechanism of deduction (the subject of a system) leading from y1,y2..y0 to x. That we can define our own components for use as modules in models, or 'schematic systems', only serves to demonstrate the implausibility of non-relativistic alternatives.

If the Devil resides in a specific location, then deflationism and reductionism are actually hostile to relativism. A conscientious relativist would rather be anything but a relativist. :) -

Relativism does not, can not, or must not obtain? Good luck.Are you sure this is a good idea?

-

Relativism does not, can not, or must not obtain? Good luck.

https://philpapers.org/browse/ontologyWhat's your ontology? — Manuel

Not sure what to say aside from "counting is no miracle."So it's not simply circular, it's also referential. — Wayfarer

Zophie

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum