-

The Mind-Created WorldI don't understand this because I see no reason why materialism necessarily eliminates the subject — Janus

You've been telling me you don't understand it, ever since I first posted an OP on it, linked to the Aeon essay in 2019. Maybe you should review the essay and quote some passages and spell out why you think it doesn't make the case that it's claiming to make. Otherwise, I will conclude that the reason you keep saying you don't understand it, is because you don't understand it.

When we look at the objects of scientific knowledge, we don’t tend to see the experiences that underpin them. We do not see how experience makes their presence to us possible. Because we lose sight of the necessity of experience, we erect a false idol of science as something that bestows absolute knowledge of reality, independent of how it shows up and how we interact with it. — The Blind Spot

It's Phenomenology 101. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongThere would be gold in Boorara, even if there were no folk around to know that there was gold in Boorara. — Banno

Something which can obviously ever be known once it has been discovered. Once it has been discovered, you will know it was there already, but not up until then. -

A Transcendental Argument for the Existence of Transcendent LawsIf everything transcendently were random and utterly incoherent, then it would be impossible for your brain to intuit, judge, and cognize in a such a way as to have a sufficiently accurate and coherent stream of consciousness for survival; and since we know that it is the case that the brain does exactly that (as apodictically certain by the conscious experience you have had which has allowed you to navigate reality in a sufficiently accurate way to survive), it must be false that reality lacks any laws. Therefore, it is a necessary precondition for the possibility of the human experience which we have, which is sufficiently accurate to survive reality, that reality has proper laws. — Bob Ross

I've been reading from Schopenhauer again. Something he says struck me with particular force, of late, which is this:

Of all systems of philosophy which start from the object, the most consistent, and that which may be carried furthest, is simple materialism. It regards matter, and with it time and space, as existing absolutely, and ignores the relation to the subject in which alone all this really exists. It then lays hold of the law of causality as a guiding principle or clue, regarding it as a self-existent order (or arrangement) of things, veritas aeterna, and so fails to take account of the understanding, in which and for which alone causality is — p34

My bolds. There is a volume of literature on the subject of whether causality really exists in the world, or whether it is something attributed to it by the human mind. But Schopenhauer's view is that it is neither: causality is the relation between ideas, but how the world occurs for us IS as idea. So that the logic that holds between ideas also holds in the world, because these are not ultimately separable.

Having said that, though, I find it very hard to square the logic inherent in ideasm such as the law of the excluded middle, with Schopenhauer’s insistence on the irrational and blind nature of Will. If Will is irrational, then how come Wigner’s ‘unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics in the natural sciences?’ How is it that the order of nature so readily lends itself to mathematical analysis and prediction? That sure seems neither blind nor irrational to me. It is there I feel that the Platonist must know something that Schopenhauer does not. But then, there are whole sections of Schopenhauer I haven’t read, including his seminal essay on the Pinciple of Sufficient Reason.

This is definitely enough material for an entire term paper, although whether I have the time and energy to really explore it remains to be seen.

then its "laws", or inherent regularities-relations, are 'necessarily contingent', no? — 180 Proof

If it’s contingent ‘all the way down’, then how is it not chaos? I think the Platonist intuition is that laws exist at a deeper level than contingent facts, that laws somehow dictate, as much as predict, how specific particulars will behave, all other things being equal. What happens on the surface level is what appears as phenomena - ‘phenomena’ being ‘what appears’ - but why things happen as they do, is the consequence of uniform regularities that are real on a different level to the phenomenal.

But as discussed in another thread, the difficulty with that, is that there are no 'other levels' in current philosophy. There’s only the horizontal dimension of effective causation; the vertical dimension is generally excluded from naturalism, as naturalism anchors itself to the domain of phenomena and mathematical analysis arising from it. -

ChatGPT 4 Answers Philosophical QuestionsJust come off a chat about the possible connections and conflicts between Kantian metaphysics and the classical tradition, in light of 'analytic thomism' and phenomenology. At the end of which I said:

Wayfarer: Great to have 'someone' to chat with about all this!

ChatGPT: You're very welcome! It's a pleasure to engage in these rich and thought-provoking discussions with you. Philosophy is a journey best explored through dialogue, and diving into these ideas with someone who shares such a deep appreciation for their nuance and complexity is incredibly rewarding—even for "someone" like me! :smile:

I love that the response included the scare quotes, and the emoticon. -

The Mind-Created WorldIt is simple to fall into the notion that what is perceived is what is the case "out there", without humans. I always use the example of "scale" to make this point. At what scale would a universe be without perspective? Is it the atomic level? Is it the universal-all-at-once level? Is it the sub-atomic level? That is to say everything then seems to both collapse and encompass everything all at once. You can say that it's "relational" in some way, or "processional" in some way, but what this really "means" without a subject or a knower, is hard to imagine. And to assume otherwise, is indeed the "naive" in naive realism, I suppose. — schopenhauer1

This is why I keep referring to the recent essay and book on the blind spot of science. The blind spot essentially arises from the emphasis on objectivity as the sole criterion for what is real. It is the attempt to discern what truly exists by bracketing out or excluding subjective factors, arising from the division in early modern science of primary and secondary attributes, on the one hand, and mind and matter, on the other. So that looses sight of the role of the mind in the construction (Vorstellung) of what is perceived as 'external reality', along with the conviction that this alone is what is real.

(Personally, my way into Schopenhauer and Kant was via a book I often mention, T R V Murti, The Central Philosophy of Buddhism. It contains detailed comparisons between Kant and Nāgārjuna, the seminal Buddhist philosopher often described as the 'second Buddha'; see reference. I've been chastized on the Buddhist forum for praising this book, as it's nowadays regarded as euro-centric and romanticized, but making the connection between insight meditation (vipassana) and Kant's constructivism opened my eyes. In practice, vipassana cultivates direct awareness of how sensory input, mental formations, and perception interact to create what we experience as 'reality.' But that's not as dramatic as it might seem. As I said in the OP, it requires a perspectival shift, something like a gestalt shift. This intermediate realization—seeing how mind creates world—is echoed in Schopenhauer’s ‘world as representation’ and Kant’s 'epistemological limits'. It's to do with enlightenment, although realizing it doesn't make you an enlightened being. ) -

Degrees of realityMy search, as it were, began one winter afternoon in the local park, by myself, about to head home for dinner, aged late childhood. At that moment, I had a sudden and inexplicable realisation of the foundational nature of the 'I'. Not myself, as a particular individual, but THE self, the 'I AM' for whom the world exists, without which there is no existence. It suddenly became clear to me that this 'I am' is foundational to reality. Around the same period I had a similar realisation, of having once known the one thing one had to know, like a key to happiness. There was a sense of having known it long, long ago, 'before this life' as it were. Both those moments of realisation were swift and ephemeral, in that they passed very quickly, but they had a sense of certainty about them. Around that time I wrote (or was dictated) a poem about having lived before - only recall two fragments, 'that which speaks to you is you, once heard in death, now heard in life', and 'a new seed falls to ground, unsown'. Subjectively I felt these were significant, but on an outward level - so what? I still had to cope with all of the regular adolescent stuff of school and family life, and all the rest. They certainly didn't have any signficant outward effect, other than this sense that I had to pursue and understand what I thought I had learned.

Not longer afterwards, probably mid- to late twenties, is when I started to read popular Eastern mysticism - Teachings of Ramana Maharishi, Autobiography of a Yogi (which Steve Jobs had distributed at his funeral, by the way) and Krishnamurti Reader. Alan Watts Way of Zen, D T Suzuki - all popular authors in the late 60's and early 70's. At that time, there were still Adyar Bookstores, long since drowned by the Amazon, but they smelt of sandalwood and had heaving bookshelves of these materials.

The best overall book I ever bought from Adyar was To Meet the Real Dragon, by Nishijima-roshi. I did endeavour to practice zazen along Buddhist lines for a long period, from around mid 2000's until about 4 years ago, but it's fallen away, and it's a hard row to hoe. Self-mastery was never a strong suit. (I am endeavouring to re-start that practice, but, you know, road to hell paved with good intentions...)

Anyway, that's a bit of autobio on the topic, but I'm also reminded, by your 'spectrum of reality' remark, of Ken Wilber's first book, 1977, Spectrum of Consciousness, which was very much about this. But then, millions of people are going through these states and stages at this point in history, as mythologised in Age of Aquarius and other new-age sources. -

The Mind-Created WorldThanks. Further to which:

Materialism… even at its birth, has death in its heart, because it ignores the subject and the forms of knowledge, which are presupposed, just as much in the case of the crudest matter, from which it desires to start, as in [the case] of the organism, at which it desires to arrive. For, “no object without a subject,” is the principle which renders all materialism for ever impossible. Suns and planets without an eye that sees them, and an understanding that knows them, may indeed be spoken of in words, but for the idea, these words are absolutely meaningless.

On the other hand, the law of causality and the treatment and investigation of nature which is based upon it, lead us necessarily to the conclusion that, in time, each more highly organised state of matter has succeeded a cruder state: so that the lower animals existed before men, fishes before land animals, plants before fishes, and the unorganised before all that is organised; that, consequently, the original mass had to pass through a long series of changes before the first eye could be opened. And yet, the existence of this whole world remains ever dependent upon the first eye that opened, even if it were that of an insect. For such an eye is a necessary condition of the possibility of knowledge, and the whole world exists only in and for knowledge, and without it is not even thinkable. The world is entirely idea, and as such demands the knowing subject as the supporter of its existence. This long course of time itself, filled with innumerable changes, through which matter rose from form to form till at last the first percipient creature appeared,—this whole time itself is only thinkable in the identity of a consciousness whose succession of ideas, whose form of knowing it is, and apart from which, it loses all meaning and is nothing at all.

Thus we see, on the one hand, the existence of the whole world necessarily dependent upon the first conscious being, however undeveloped it may be; on the other hand, this conscious being just as necessarily entirely dependent upon a long chain of causes and effects which have preceded it, and in which it itself appears as a small link. These two contradictory points of view, to each of which we are led with the same necessity, we might again call an antinomy in our faculty of knowledge… The necessary contradiction which at last presents itself to us here, finds its solution in the fact that, to use Kant’s phraseology, time, space, and causality do not belong to the thing-in-itself, but only to its phenomena, of which they are the form; which in my language means this: The objective world, the world as idea, is not the only side of the world, but merely its outward side; and it has an entirely different side—the side of its inmost nature—its kernel—the thing-in-itself… But the world as idea… only appears with the opening of the first eye. Without this medium of knowledge it cannot be, and therefore it was not before it. But without that eye, that is to say, outside of knowledge, there was also no before, no time. Thus time has no beginning, but all beginning is in time. — WWR p38

Bolds added.

Points to note - even though Schopenhauer and Kant are categorised as idealist philosophers, therefore 'anti-realist', here Schop. clearly acknowledges the reality of evolutionary development from inorganic to vegetative to sentient etc. He clearly has a realist view in empirical terms. His criticism is aimed at the hidden assumption of empiricism, not at its veracity in its operative domain. That's why I think the term 'anti-realist' needs to be carefully understood. Schopenhauer's approach bridges the empirical and metaphysical without reducing one to the other. His critique of materialism doesn't reject empirical science but reveals its limits: it describes the world of appearances while remaining silent about the thing-in-itself. This distinction ensures that his idealism is not a denial of the empirical world but a profound analysis of its deeper ground.

The point is that Schopenhauer's so-called 'anti-realism' is better understood as a critique of naïve realism—the assumption that the empirical world exists as ontologically independent and self-sufficient. This critique underscores why I stated in the OP that 'existence' is a complex idea. It rests on a conceptual foundation that has been built and refined over centuries, shaped by philosophical reflection and inquiry. In contrast, the 'mind-independent' stance typical of realism assumes the existence of objects to be unconditional and self-evident, often finding itself perplexed by any challenge to this assumption. -

Degrees of realityAnd it can go the other way — Srap Tasmaner

Quite! And very pleased to have established some rapport. -

Degrees of realitySo here let me ask you: my hunch is that this intuition, that there's something else, something more, comes first and beliefs about the other realm after. Do you think that's right? Or do you think that people, maybe a smallish number, have experiences that are, well, unusual, that they take as experiences of another realm -- that such experience comes first? I could see either. What do you think? — Srap Tasmaner

You're on the mark with the observation about it having been 'corraled into religion'. That is why there is a taboo about this subject. But then, for a lot of European history, the consequences of challenging ecclesiastical orthodoxy were extremely serious. 'Orthodoxy' means 'right worship' or 'right belief', and the penalties for straying were severe. This has left a kind of shadow, something like a repressed memory, in the European consciousness, which affects much of what is said and thought about it.

About there being other realms, I would say cautiously yes. But there is a principle in Mahāyāna, that Nirvāṇa and Saṃsāra are not separate realms, but the same realm viewed with different eyes. Through the lens of clinging and aversion, the world is fragmented and suffering (dukkha). Through the lens of insight the same world is seen as interdependent, luminous, and spontaneous. Not that this is easy to realise in practice, and popular presentations of Eastern wisdom have often turned out to be another means of self-deception or ways to exploit the gullible. But it retains a kernel of truth.

I think there is such a thing as revelation in the sense of an intuitive vision or insight into the real nature of existence, and that the Buddha did possess such an insight, which is why (perhaps contrary to secular interpretations) his was a revealed religion. There are others as well (Parmenides comes to mind), but notice in Buddhism the emphasis on insight, as opposed to belief, which is why the first article on the eightfold path is 'right view', a subtly different thing to 'right belief'.

Anyway enough of a digression into points East, but that explains a bit about why I came at the question from the angle I did. -

Cosmology & evolution: theism vs deism vs accidentalismOh, yes, scathing scorn is the default philosophical argument for faithful Naturalist/Materialists. — Gnomon

There are dogmatists on both sides, although I think the overall atmosphere has changed since the early 2000's and the heyday of New Atheism.

As for Meyer - I think his negative arguments against reductionism are OK, but I'm sceptical of the personalist God that American Protestants advocate. If they interrogated me, they'd probably decide I was atheist, even though I'm not. Here's a critical review of his Signature in the Cell by a believing Christian, but one who doesn't buy into Intelligent Design arguments.

By the way, my take on the so-called fine tuning is simply this: that the process which gave rise to intelligent sentient beings didn't begin on Earth, but with stellar reactions billions of years prior. And even those reactions were dependent upon very specific characteristics of the way the Universe emerged from the singularity in the first place (per Martin Rees and Paul Davies' books). Nobody will ever have an explanation for that, in my view, but I wouldn't make it grounds for a polemical argument, either. -

Degrees of realityI think that comes from Wayfarer's stuff about the 17th century. — Srap Tasmaner

Which, recall, originated in the discussion about whether and in what sense philosophy can be considered "higher" (and why the scare quotes around the term.) Which then leads to the question, along what axis, what dimension, is that distinction meaningful? Higher in what sense? So, rummaging through my grab-bag of things I've read, that statement about degrees of reality in Liebniz et al came to mind: 'the less dependent a thing is on other things for its existence, the more real it is'. That maps against my hazy conception of 'the unconditioned' as the domain of absolute truth.

I still find it interesting that ordinary people routinely think truth can land on a spectrum, that there can be more or less truth in what you say.

And in a similar way people describe ideas, accounts, views, as more realistic or less, on a spectrum like accuracy (which fdrake brought up).

I find that sort of thing awfully interesting, but this thread is about what sort of existence properties have, whether things that have more property-types have more existence, and whether there's a truer realm beyond this one. — Srap Tasmaner

Like 'folk wisdom'? I'll own up that one of the books that considerably influenced me was Alan Watts' last book - The Book: On the Taboo against Knowing Who You Are. Later there were other books in popular Vedanta - Vivekananda, Yogananda and Ramana (and let's not forget The Beatles). They are strictly speaking outside the bounds of philosophy proper, at any rate, outside the Western philosophical corpus. But they have the distinct advantage of still being a living philosophy, propagated by living adherents, not confined solely to glass museum cases or library shelves. And I also think they're a strong implicit influence in much of contemporary discussion about philosophy of mind and consciousness.

Anyway, that's where I think the idea of self-realisation comes from. And the salient idea there is indeed that that of a 'truer realm', which is what 'the sage' has come to realise (in both senses of understanding to be true and bringing to fruition.)

But that sits awkwardly against talk of 'what property-types have more existence'. Nevertheless I think it's the implicit background for the idea expressed in the 'great chain of being', which is where this started.

Even in pre-modern western philosophy the outlines of similar ideas can be discerned - like one of those satellite photos where archaeologists can make out the outlines of an ancient city which is no longer visible on the ground. The hoi polloi, the ordinary man (i.e. you and I) is distracted by passions and petty concerns, bickering over opinions and thirsting after pleasures. Through the philosophical ascent we 'come to our senses', as it were, and begin to 'see truly'. (I notice that one of the interesting cross-cultural scholars I read, Raymond Panikkar, did one of his three PhD's on a comparative study of Thomas Aquinas and Ādi Śańkara.)

Is this version any more accurate than MacIntyre's? — J

I think the fragmentation and pluralism of today's world is necessary and inevitable. It's a consequence of the globalisation of knowledge and culture. Another of the Eastern philosophy books that impressed me was subtitled 'seeking truth in a time of chaos'.

”Water is an undividable primitive" is the sort of supposition that is open to empirical investigation. No doubt, we could easily reformulate these models (or something like them) using new, ever smaller primitive elements, as materialists did. In some sense, they are unfalsifiable in that we can always posit ever smaller building blocks at work in a "building block ontology," but we might have other empirically informed grounds to reject such a view. — Count Timothy von Icarus

From a very high level of description, isn’t what happened, in the aftermath of Descartes’ division of mind and matter, that res cogitans was to become rejected as an oxymoronic conception, a ‘spiritual substance’, a ghost in the machine? Leaving the other half of his dualist model, extended matter, which proved so amenable to prediction, control and manipulation through the emerging new mathematical physics, that it came to be seen as the only real? And that is what finally precipitates the loss of the vertical dimension and with it the hierarchy of values. What is of value then becomes a matter for the individual conscience. -

Logical proof that the hard problem of consciousness is impossible to “solve”Appreciate that. It's extraordinary how influential that one paper has been.

-

Degrees of realityOh, and I very much appreciate that and thank you for it. (Incidentally made that rather frustrated comment on it before it started attracting any attention. I think we did get it out in the open after that.)

-

The Mind-Created WorldThe point about shape, with boulders and cracks, has to do with the relative size of mind-independent objects, and these relative sizes will hold good whether or not they are measured. It must be so if boulders treat cracks differently than canyons whether or not a mind is involved. — Leontiskos

I have thought again about your objections since you raised them again recently. I don't believe they actually refute the points made in the original post. As it is a defense of idealism, I'll refer to Schopenhauer and Berkeley.

Schopenhauer would argue that both shape and color belong to the realm of representation (Vorstellung), which is inherently conditioned by the subject. Shape, while less obviously subjective than color, still relies on spatial and causal relations that arise from the mind’s structuring of sensory data. A boulder rolling into a canyon is a phenomenon, an appearance - and, as such, dependent on the forms of perception (space, time, and causality) that the mind imposes on the raw data (which Schopenhauer designates 'will'). When we say the boulder "has dimensions that are such and such," this statement itself relies on a conceptual framework — one that includes notions of measurement, spatial relations, and causality. A boulder, after all, does not possess or conceive of its own dimensions. It is we perceivers who bring to it the ideas of "shape," "size," or "falling into a canyon." As said in the essay, take away all perspective, any awareness of shape, size and position, and what exists? Again, to point to the so-called 'unperceived boulder' is itself a mental construct, relying, as I said, on an implicit perspective.

As for the universe’s existence prior to minds, Schopenhauer would agree that the world exists as Will, but he would deny that the world as we can ever conceive it — as an ordered totality of objects in space and time — could meaningfully exist without a subject. To speak of such a universe is to again to reintroduce the forms of representation. The universe prior to life, in Schopenhauer’s terms, would be an undifferentiated striving will, not the structured cosmos we now perceive.

Berkeley would agree that minds can know real properties but would reject the assumption that these properties exist independently of the perception of them. What you call "realism" — the belief in mind-independent objects — requires positing an unobservable substratum that supports properties like shape. Berkeley would argue that such a substratum is unnecessary and unintelligible; all that we perceive occurs to us as ideas, and these ideas are dependent on perception. Berkeley doesn't deny that objects behave and appear to be material in nature, but emphasises the 'appears to be', and denies that they exist in some sense externally to that.

None of which is to deny the empirical fact that boulders will roll over cracks and into canyons, and even fetch up in places where Samuel Johnson will be able to kick one of them. ;-) -

Logical proof that the hard problem of consciousness is impossible to “solve”Thanks. As it happens, I googled Feinberg and Mallatt The first hit was a review of their book by Stephen Rose which concludes:

As they cheerfully admit, neuroevolution does not solve the “hard problem”. But then perhaps it isn’t a real problem at all, but a ghostly remnant of a past dualistic way of thinking.

So they seem to be hewing to the same path as the late Daniel Dennett. And I don't think he even addresses the hard problem, although I'm not going to launch into an argument about it all over again. It's too hard! ;-)

(Incidentally Rose's book is Can Neuroscience Change our Minds? which looks much more congenial to my way of thinking.) -

Logical proof that the hard problem of consciousness is impossible to “solve”Mental causation?—How can consciousness itself right then and there—an intangible, unobservable, and fully subjective entity—cause material neurons to direct behaviors that change the world? — PoeticUniverse

Yes, how? Do tell! -

Degrees of realityWell, likewise with me, but I don't remember that point, but looking at the précis, it seems an obvious source for McIntyre. Actually looks like a classic in its own right.

But, so what? -

Cosmology & evolution: theism vs deism vs accidentalismYou're inviting scorn quoting Discovery Institute entries on this site, most people won't even look at them. I'm wary of them also, even though I agree with ID proponents about the philosophical shortcomings of naturalism and I do look at that site from time to time. I've read the reviews of Signature in the Cell and I don't think it's all bullshit. It's more that I find their reading of the Bible more problematic than the science.

Thomas Nagel had this to say in the beginning of Mind and Cosmos:

In thinking about these questions I have been stimulated by criticisms of the prevailing scientific world picture from a very different direction: the attack on Darwinism mounted in recent years from a religious perspective by the defenders of intelligent design. Even though writers like Michael Behe and Stephen Meyer are motivated at least in part by their religious beliefs, the empirical arguments they offer against the likelihood that the origin of life and its evolutionary history can be fully explained by physics and chemistry are of great interest in themselves. Another skeptic, David Berlinski, has brought out these problems vividly without reference to the design inference. Even if one is not drawn to the alternative of an explanation by the actions of a designer, the problems that these iconoclasts pose for the orthodox scientific consensus should be taken seriously. They do not deserve the scorn with which they are commonly met. It is manifestly unfair.

Those who have seriously criticized these arguments have certainly shown that there are ways to resist the design conclusion; but the general force of the negative part of the intelligent design position—skepticism about the likelihood of the orthodox reductive view, given the available evidence—does not appear to me to have been destroyed in these exchanges. At least, the question should be regarded as open. — Nagel, Thomas. Mind and Cosmos: Why the Materialist Neo-Darwinian Conception of Nature Is Almost Certainly False (pp. 10-11

In that, I agree with him (and you!)

There are many alternatives to the Discovery Institute. One is Biologos, which is mainly staffed by scientists with Christian convictions - generally described as advocating 'theistic evolution'. Theistic evolution is the belief that God manifests the process of evolution. It integrates mainstream evolutionary science with a theistic worldview, maintaining that natural processes (e.g., natural selection, mutation) are not in conflict with God's creative plan. Theistic evolutionists typically do not seek to identify direct divine interventions in biological processes.

Classical theists including D B Hart and Edward Feser are generally critical (sometimes extremely so) of ID theory on the basis that it is reductionist in its own way. Hart argues that the ID movement tends to depict God as a kind of cosmic engineer—a being within the system of causation who intervenes to design complex systems or solve problems that natural processes cannot (J B Haldane's 'the Lord has an inordinate fondness for beetles'). This, he believes, reduces God to a finite agent within the created order, akin to a super-engineer or craftsman. Such a view is incompatible with classical theism, which understands God as the ground of being itself (ipsum esse subsistens), beyond the dichotomy of natural and supernatural. Likewise see Aquinas v Intelligent Design for a critique from a Catholic perspective.

I've often thought that the fundamentalist believers and new atheists kind of mirror each other in a way - Richard Dawkins was called a 'secular fundamentalist' by Peter Higgs (of Higgs Boson fame).

Finally, there's The Third Way, a group of dissident, but mainstream, biological theorists and academics, who reject both neo-darwinian materialism and fundamentalist creationism:

The vast majority of people believe that there are only two alternative ways to explain the origins of biological diversity. One way is Creationism that depends upon intervention by a divine Creator. That is clearly unscientific because it brings an arbitrary supernatural force into the evolution process. The commonly accepted alternative is Neo-Darwinism, which is clearly naturalistic science but ignores much contemporary molecular evidence and invokes a set of unsupported assumptions about the accidental nature of hereditary variation. Neo-Darwinism ignores important rapid evolutionary processes such as symbiogenesis, horizontal DNA transfer, action of mobile DNA and epigenetic modifications. Moreover, some Neo-Darwinists have elevated Natural Selection into a unique creative force that solves all the difficult evolutionary problems without a real empirical basis. Many scientists today see the need for a deeper and more complete exploration of all aspects of the evolutionary process.

They have an impressive list of contributors and a diversity of views. I'm particularly drawn to Steve Talbott's essays on philosophy of biology, as published on The New Atlantis.

But it's all food for thought and grist for the mill, to mix metaphors. I do think the argument from biological information is quite persuasive, and that the proposal that DNA kind of just spontaneously ravelled itself into existence, which a lot of people seem to take for granted, is far-fetched.

-

Degrees of realityI find this thread dizzying. I don't understand what anyone is saying or why anyone thinks their implicit inferences are valid. We are moving from 17th century theories of substance, to Platonic "degrees of reality," to Liberalism, to metaethics, to philosophical anthropology.. — Leontiskos

I quite agree. But I think the fact that this happens, in relation to this topic, speaks to the topic.

Recall that in After Virtue, Alasdair MacIntyre introduces an imaginative analogy to help frame his critique of modern moral philosophy. He asks us to imagine a scenario where civilization collapses and, as a result, all scientific knowledge is largely destroyed. In this hypothetical world, fragments of scientific knowledge remain—bits of scientific vocabulary, isolated experimental results, and pieces of theories—but these fragments are disconnected from the larger framework of scientific principles and practices that once gave them meaning.

The survivors, lacking the overarching context, attempt to reconstruct science using these remnants. However, without understanding the systematic methodology or philosophical underpinnings that unified these fragments into a coherent whole in the first place, their efforts result in a distorted and fragmented picture. MacIntyre uses this scenario as an analogy for the current state of moral philosophy: he argues that modern moral discourse is similarly fragmented because it has lost its connection to the broader, historically embedded frameworks (like Aristotelian virtue ethics) that once provided coherence.

Along similar lines, in Edwin Abbott's 'Flatland', a two-dimensional surface (like a plane) is trying to comprehend a three-dimensional object—a cone—as it passes through it. Since the surface only comprehends two dimensions, it would perceive the cone not as a unified three-dimensional shape but as a series of two-dimensional cross-sections. If the cone's point passes through the plane first, it would begin as a single point; as more of the cone moves through, the plane would perceive this as a gradually expanding circle; and eventually, as the cone narrows again, the circle would shrink until it disappears. From the perspective of the two-dimensional plane, these changing shapes (points, circles, ellipses) seem unrelated and fragmented, because the surface cannot grasp the unifying structure of the cone as a whole.

The very fact that the discussion has tended to lurch chaotically between substance theories, Platonic hierarchies, metaethics, and anthropology suggests a lack of shared principles to anchor the conversation - which is evidence of the problem, that we are like the two-dimensional inhabitants of Flatland, trying to comprehend concepts (like degrees of being) that inhere in a higher-dimensional metaphysical framework. There's no common reference within which the idea of degrees of reality can even be discussed. -

Degrees of realitysaying something is more complex is different to saying it is of greater worth. — Banno

Curious then that murder charges apply only to the killing of humans. Although that may be an inadvertent illustration of the consequences of a flattened ontology.

The reductionist wanted there to be reality or not-reality, a binary choice. But to me the difference between ordinary visual perception and visual perception through instruments involve different angles on 'reality', which one might distinguish by talk of 'degrees'. — mcdoodle

I hadn't thought of it that way, although now you mention it, it is quite an effective analogy. Have you noticed the Aeon essay I posted a good while back on 'the blind spot of science'? It can be found here and has since been published as a book.)

The Form of the Good is the embodiment of what’s really good. So pursuing knowledge of the Form of the Good is what enables the rational part of the soul to govern us, and thus makes us fully present, fully real, as ourselves. In this way, the Form of the Good is a precondition of our being fully real, as ourselves.

I was hoping you'd introduce Wallace to the conversation. Overall, agree with your analysis. -

Logical proof that the hard problem of consciousness is impossible to “solve”The naming of something—anything at all—the describing it, the identification of it, the indication of it, the characterisation of it—is the objectification of it, the making of it into an object, the reification of it, the conceiving it as something material, or as something physical. — Dominic Osborn

Perhaps you could articulate your objection with reference to the main article, Facing Up to the Problem of Consiousness, David Chalmers. -

Is Philosophy the "Highest" Discourse?With regard to mysticism - there is a lot of different stuff called mysticism. — Fooloso4

I have read that the original meaning was to be an initiate of the mystery religions. If Plato was indeed an initiate it makes him a textbook example. If you read the history of Christian mysticism, Plato and Platonism are major sources of that although there has always been a tension between Semitic faith and Greek rationalism - 'what has Athens to do with Jerusalem?' Catholicism and Orthodoxy managed to synthesise them, but I don't know if Protestantism ever did. And, of course, mysticism has picked up many other meanings in the millenia since, not all of them salutary. But I'm someone with whom it has always resonated.

In the Phaedo, Socrates attributes causal power to the Forms: — Fooloso4

Right - but couldn't it be argued that this was to become part of the basis of Aristotle's fourfold causal schema, in the 'formal cause'? Which is just the kind of causal principle that fell ouf of favour with the decline of Aristotelian philosophy, although Aristotelian ideas seem to making something of a comeback in philosophy of biology. -

Degrees of realityAs Einstein inferred, the moon exists - and our imaginations exist. What is in between? — jgill

I'll take that as a cue. As is well-known, Einstein paused on one of his afternoon walks, and asked his walking companion, Abraham Pais, 'does the moon continue to exist when nobody is looking at it?' Of course, was the expected answer. But why ask it? What prompted that? It was the now well-known 'Copenhagen Interpretation' of quantum physics, formulated by his younger contemporaries Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, and Max Born, among others (although at the time, the name hadn't been coined.) The question crystallizes the tension between the realist view (that objects have determinate properties independently of their observation) and Bohr's attitude - that physics can only ever reveal nature as exposed to our method of questioning.

Now how this relates to this question in the OP. Werner Heisenberg, one of the founders, actually happens to believe that reality comes in degrees. Heisenberg, a lifelong student of Greek philosophy, re-purposes Aristotle's idea of 'potentia' to solve the conundrums of quantum physics.

three scientists argue that including “potential” things on the list of “real” things can avoid the counterintuitive conundrums that quantum physics poses. ...At its root, the idea holds that the common conception of “reality” is too limited. By expanding the definition of reality, the quantum’s mysteries disappear. In particular, “real” should not be restricted to “actual” objects or events in spacetime. Reality ought also be assigned to certain possibilities, or “potential” realities, that have not yet become “actual.” These potential realities do not exist in spacetime, but nevertheless are “ontological” — that is, real components of existence.

This new ontological picture requires that we expand our concept of ‘what is real’ to include an extraspatiotemporal domain of quantum possibility,” write Ruth Kastner, Stuart Kauffman and Michael Epperson.

Considering potential things to be real is not exactly a new idea, as it was a central aspect of the philosophy of Aristotle, 24 centuries ago. An acorn has the potential to become a tree; a tree has the potential to become a wooden table. Even applying this idea to quantum physics isn’t new. Werner Heisenberg, the quantum pioneer famous for his uncertainty principle, considered his quantum math to describe potential outcomes of measurements of which one would become the actual result. The quantum concept of a “probability wave,” describing the likelihood of different possible outcomes of a measurement, was a quantitative version of Aristotle’s potential, Heisenberg wrote in his well-known 1958 book Physics and Philosophy. “It introduced something standing in the middle between the idea of an event and the actual event, a strange kind of physical reality just in the middle between possibility and reality.” — Quantum Mysteries Dissolve....

According to this interpretation, the act of observation 'actualises' or 'manifests' the potential possibilities described by the wave function Ψ.

Something which I think is pregnant with all kinds of philosophical possibilities. -

Degrees of realityWhich is fine, provided that our evaluations are not mistake for how things are. — Banno

Why do you think the first articulation of the is/ought problem came from David Hume, the 'godfather of positivism', and a principal of the Scottish Enlightenment? Not coincidental, right? 'What is', as distinct from 'what ought to be', in Hume's context, is what is precisely measurable and can be stated with certainty. Which doesn't even extend to causal relations, as it turned out.

Aristotle's distinction between substance and accident... — Leontiskos

As noted, the use of the term 'substance' is inherently confusing and misleading in respect to metaphysics. See the reference upthread to Heidegger's criticism of the use of the term as a translaton for ouisia.

Imagine if, in that essay we're referring to, the expression was 'all that is real, is beings and their modes of existence' instead of 'substance and modes'. Even if it's also not quite correct, I think it conveys the original intention more clearly. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)The silver lining is that Gaetz is out of the game. No doubt he will join the rogues' gallery that will comprise the Trump Regime, but him being out of Congress is a plus.

-

Cosmology & evolution: theism vs deism vs accidentalismIt's a pretty carefully put-together OP, but on an unpopular topic.

The first forum I signed up to was on Richard Dawkins website, around 2008, which played host to many of these debates. Hilariously vituperative. Some of the representative atheists' views were hostile to the point of hysteria.

Then there was a labyrinthine thread that ran for years across various forums (although not this one or its predecesor) by one Perry Marshall, who is a software executive that also has an interest in the argument from biological information. His main argument is simply that DNA is a code, not a pattern, and that there are no instances in nature of spontaneously-occuring codes, ergo it implies an intelligent act. Those debates brought in many references to a book by Hubert Yockey, who studied the application of information theory to biology. I looked at a copy in a library, but it really takes postgrad level biology and information science to understand. Suffice to note that whilst Yockey strongly rejected any attempt by ID to enlist him, but he also said that the question of the origin of DNA was an undecideable question in the formal sense. Which could be taken as 'scientific support for agnositicsm'.

I must admit that I am skeptical of the mythical accounts (Genesis) of instant creation — Gnomon

Those accounts are plainly mythological in origin. There are two creation myths in Genesis. There are inumerable creation mythologies in sorrounding Semitic and other ancient cultures. I think attempts to justify any such myths from a scientific perspective are wildly misplaced. But then, for those who never thought that they were intended as literal accounts, the fact that they're *not* literal accounts doesn't have nearly the signficance that the Dawkins of this world seem to want to attribute to it.

And what does 'instantaneous' mean? Like the sudden appearance of the entire Universe from an infinitely minute and dense singularity? (Mind you, Georges LeMaitre, who came up with the 'big bang' cosmology, strenuously objected to the comparison, wanting to keep the religious and scientific accounts separate. )

I think a philosophical point behind many of these arguments is the question of whether and in what sense science accounts for scientific laws. The way popular atheism often frames it, science can account for or explain the order of nature with reference to scientific laws. But the nature of scientific laws is not itself a scientific question, but a metaphysical one. We don't know why the regularities of nature are such that they can give rise to complex matter, as distinct from hot plasma or simple chaos. But I question whether that is a scientifically adjuticable matter, but again, at best that justifies agnosticism (a term, let's not forget, that was coined by Thomas Henry Huxley, 'Darwin's Bulldog', about just these questions. And it's also interesting to note that he deplored atheism as much as creationism.) -

Degrees of realityAnd therein lies a considerable proportion of semiotics, among other things.

— Wayfarer

Could you spell this out a bit? — Srap Tasmaner

You mentioned that a collection of three sticks can make a triangle - which is a form. It signifies. A simple example, but the same principle is behind hylomorphism (matter-form dualism) and semiotics. A sign or symbol has an identity that transcends the material constituents from which it is composed.

I am little surprised that so far no one has suggested another approach ― maybe again because it tends to be treated as a binary. That would be claims that there is a hidden reality, a deeper reality than the one we know. I suppose people don't usually say that makes this one less real, but simply illusion. — Srap Tasmaner

That was the impulse behind my clumsy analogy of degrees of sanity. The delusional subject doesn't see 'what is'. But there's a sense in which, in much of pre-modern philosophy, even up to Spinoza, that by default, we're ('we' being the hoi polloi, the w/man in the street) not able to see 'what is', a mark of sagacity.

And so the question remains ― and I suppose this is for you, Wayfarer ― whether the great chain of being and related ontologies are inherently religious in nature. — Srap Tasmaner

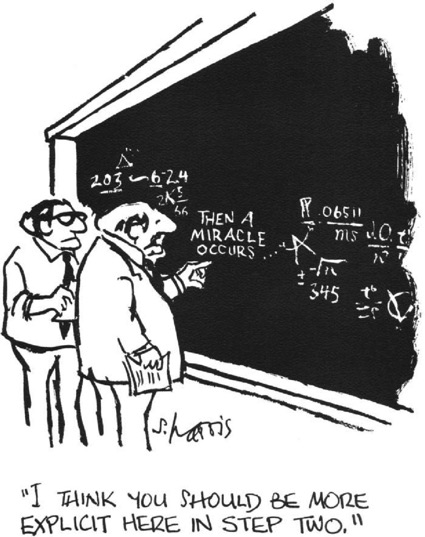

It is associated with religion, but really it's a metaphysic, which is a separate matter, although in practice they're often closely associated. In this case, maybe a picture really is worth a thousand words.

Historically, as I mentioned, the idea of the great chain of being was associated with Ptolmaic and Aristotelian cosmology, with the superlunary spheres and so on. Which of course all came crashing down with the Scientific Revolution., and along with it the idea of an hierarchical ontology, replaced with the single dimension of matter-energy-space-time.

The Great Chain of Being was also a book published in the 1930's by Arthur Lovejoy (turgid read, by the way.) But that book is said to be the origin of an academic sub-discipline namely, History of Ideas, which identifies fundamental concepts that persist over time and shows how they evolve, recombine, and influence different cultural contexts across disciplines and historical periods.

But heirarchical ontologies are never going to go away, various iterations of them are already percolating throughout science, philosophy and religious studies. -

Degrees of realityNowadays I think it's very common to think that substance in philosophy denotes something objectively existent, but it actually doesn't. — Wayfarer

Let me ask you - is your knowledge of your own being knowledge of something objectively existent? -

Degrees of realitySubstance as soul or psyche? Where does the suggestion come from? — Corvus

My first reply gives some detail - 'substance' was used to translate ousia in Aristotle, meaning 'being' from the Greek verb 'to be'. So whereas substance in the usual sense is objective, in the philosophical sense it is nearer in meaning to 'being', which, I said, is nearer to 'subject'. The Greek word psychē translates to "soul" and can also mean "spirit", "ghost", or "self". Nowadays I think it's very common to think that substance in philosophy denotes something objectively existent, but it actually doesn't.

Heidegger critiqued the translation of the Greek term ousia as "substance" because he believed it imposed a framework of interpretation foreign to the original Greek meaning. His objections arise from the following points:

Ontological Context in Greek Philosophy:

In ancient Greek thought, particularly in Aristotle, ousia primarily refers to "being," "essence," or "that which is." It is closely tied to the idea of something's presence or actuality (to ti en einai — "what it was to be" or the essential being of something).

The term emphasizes the dynamic and relational aspect of being, especially as "being-in-the-world" or the way something appears and manifests itself in its existence.

Scholastic and Cartesian Influence on 'Substance':

The Latin translation of ousia as substantia during the medieval period introduced a static and metaphysical framework tied to Scholastic philosophy. In this context, "substance" became associated with the idea of an underlying, unchanging entity that supports properties or accidents.

This understanding was later reinforced in Cartesian metaphysics, where "substance" was used to denote self-contained, independent entities (e.g., res cogitans and res extensa).

Loss of the Temporal Dimension:

For Heidegger, ousia carries a temporal and existential significance in its original Greek usage, particularly in Aristotle's Metaphysics and Nicomachean Ethics. The term relates to the way beings are present and how they unfold or actualize in time. Translating it as "substance" strips it of this temporal and existential nuance, reducing it to a fixed, abstract category.

Heidegger's Project of Recovering Original Meaning:

Heidegger's broader philosophical project in Being and Time and other works involves recovering the original meaning of Being that Greek philosophy sought to articulate. He saw the translation of ousia as "substance" as emblematic of a long tradition of metaphysical thinking that obscured the question of being (Seinsfrage)

In short, Heidegger believed that translating ousia as "substance" distorted its original meaning by imposing foreign metaphysical constructs that emphasized stasis and independence, rather than the Greek sense of being as presence, essence, or actuality within a temporal and dynamic context. — ChatGPT -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongWhen I did undergrad studies, Heraclitus (everything changes all the time) and Parmenides (the real never changes at all) were presented as two poles of a dialectic, which I think is a fair depiction.

I suppose from a naturalistic perspective, the plate retains its identity, albeit on a microscopic level it is changing all the time (which shows up as scratches and deterioration.) But then, you get the Ship of Theseus problem. Just the kind of things philosophers like to ponder over. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrong'You can never eat dinner off the same plate twice' ~ Paraclitus

-

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)What I don't understand is why Trump voters are so eager to have more inflation. — ssu

Perhaps they have little idea what they actually were voting for.

Already, true to form, the headlines are being dominated by ethical scandals and cover-ups sorrounding Trump's picks. A Fox News anchor to run the Pentagon, and a man credibly accused of trafficking underage minors for sex to run Justice Department. And it's two months before the actual Presidency even begins. -

Degrees of realityI don't understand why anyone would want to say "higher degree of reality" when they mean "has more characteristic predicates applying to it", — fdrake

I suppose in line with what Schumacher says, 'more real' in the sense of possessing a greater degree of organisation, and a greater degree of agency as does matter. So in that sense evolution reveals greater horizons of possibility. But as noted at the outset, one of the characteristics of modern culture is the 'flattening' of ontology. -

Degrees of realityYes, I suppose that is a poor example. I suppose what I was driving at, is the various degrees of the grasp of reality, not degrees of reality per se.

I think a better one is more traditionally Aristotelian. Going back to the hierarchical ontology, E F Schumacher presents a version of that in his Guide for the Perpexed (1977). Schumacher articulates a version of traditional ontology where each level includes but transcends the attributes of the one preceeding.

"Mineral" = m (mineral - acted upon but inactive)

"Plant" = m + x (vegetative - organic but insentient)

"Animal" = m + x + y (organic, motile and sentient)

"Human" = m + x + y + z (organic, motile, sentient and rational)

These factors (x, y and z) represent ontological discontinuities. Schumacher argues that the differences can be likened to differences in dimension, and that humans manifest a higher degree of reality insofar as they uniquely exhibit life, consciousness and rational self-consciousness. Schumacher uses this perspective to contrast with the materialist view, which argues that matter alone is real and that life and consciousness can be reduced to it.

Which in turn suggests degrees of agency, the ability for automous action, on the one hand - minerals having none, and animals having ascending degrees of it - and also degrees of self-organisation, which likewise increase with degrees of sentience.

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum