-

Visualization/Understanding or Obscurantist Elitism?the founders of quantum mechanics were notorious for either abandoning any attempt at the intelligibility of the atomic or grew rather pessimistic at said notion. — substantivalism

I don't think that's in the least true. You know that Neils Bohr thought that his discovery of the principle of complimentarity was one of his greatest breakthroughs. And that when he was awarded Imperial Honours by the Danish Crown, he had a Coat of Arms designed that featured the Taoist Ying-Yang symbol. It might be the case that human knowledge is forever limited in some fundamental respects. It might be the case that what we understand as the physical domain is not exhaustive of reality as a whole. Then what are you going to do, as the entire thrust of Western thought since Galileo has been that it is.

And don't fall for the dogma that metaphysics is nonsense. It is meaningful within a domain of discourse, one that has endured for millenia and still has advocates and exponents to this day. The positivist aversion to metaphysics might have been very much a manifestation of the unconscious fear of religion, arising from the tortured history of religious politics in European affairs. -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)And now he's protected by the Supreme Court decision that he's granted immunity for 'any official acts'. The Project 2025 ideologues are lined up to purge the bureacracy and, quote, 'take down the deep state leadership.' He's promised 11 million deportations and massive tarrifs. He has a hit list of his 'enemies within'.

I always feared the worst, but I think this is going to be a lot worse than I feared. I think I'm going to get my head out of news broadcasts and go back to just studying philosophy and Buddhism. -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)RFK Secretary for Health. Elon Musk, Secretary for Government Expenditure. Steve Bannon, chief press officer. Like when your jetliner starts to fall from the sky - buckle your seatbelts, put your head between your knees, and kiss your ass goodbye.

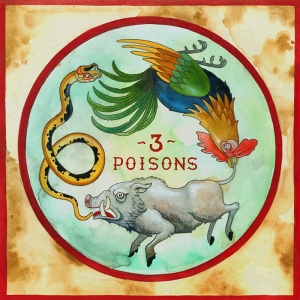

Some relevant iconography:

This icon is ubiquitous in Buddhist cultures. They are called 'the three poisons', responsible for all human misery. Snake represents hatred. Pig represents greed. Rooster is ignorance. They're running the show now. -

Withdrawal is the answer to most axiological problems concerning humansIn Buddhist cultures, unlike Christian cultures, Buddhist don't feel generally obliged to impose their religion on others. So if someone said, 'I don't see any rationale for it', they would probably say 'suit yourself!' rather than try to evangalise you.

And, I wasn't going to stay on retreat forever. I'm not a monk and at this stage of life, it's not a feasible option, although I'm very aware of the need for a kind of 'lay monasticism' of practice, recitation and renunciation of the hindrances and obstacles to spiritual growth. -

Withdrawal is the answer to most axiological problems concerning humansI went on a Buddhist retreat many years ago, and at one of the Q&A's I put my hand up, and asked a question, along the lines, 'modern life is very complex. You have relationships, financial and work obligations, bad habits develop.' And so on. The monk replied, with a broad grin, 'I know! Why do you think we're monks!'

-

The Empty Suitcase: Physicalism vs Methodological NaturalismI'm not sure where you got that definition. — L'éléphant

Physicalism is, in slogan form, the thesis that everything is physical. The thesis is usually intended as a metaphysical thesis, parallel to the thesis attributed to the ancient Greek philosopher Thales, that everything is water, or the idealism of the 18th Century philosopher Berkeley, that everything is mental. The general idea is that the nature of the actual world (i.e. the universe and everything in it) conforms to a certain condition, the condition of being physical. Of course, physicalists don’t deny that the world might contain many items that at first glance don’t seem physical — items of a biological, or psychological, or moral, or social, or mathematical nature. But they insist nevertheless that at the end of the day such items are physical. — SEP

It denies that there is an unexplained gap between the physical and the intangible, subjective experiences... — L'éléphant

It takes more than a denial, it takes an argument. The 'explanatory gap' is similar to the 'hard problem of consciousness', which is basically that physical descriptions fail to properly depict or describe the subjective sense of being, for which there is no analogy in physical terms.

What physicalism denies is that there is no explanation at all for the mind or the consciousness. — L'éléphant

What it denies is that there can't be a physical explanation for the mind. A physical explanation for the mind must be given in terms proper to physics, such as mass, velocity, number, composition, and other attributes of matter, otherwise it's not a physicalist explanation. -

Aristotle and the Eleusinian MysteriesYes, that might have been it - been a long time! - but if you're familiar with him already, you probably know that!

-

Aristotle and the Eleusinian MysteriesHave a look for The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion, Mircea Eliade. He discusses the Mysteries and also (from memory) their relationship to the ancient proto-Indo-European mystery cults that spread across the ancient world with the original Aryan peoples.

-

Aristotle and the Eleusinian MysteriesInteresting to note that one of the etymologies for 'mystic' and 'mysticism' was precisely 'an initiate into the Mysteries.'

I think scholarly opinion favours the view that Plato was an initiate, although as is well known, speaking about them was forbidden, they're secret rites (like Masonic rites in today's culture.) But many of the themes in the more spiritual of the dialogues - Phaedo, Phaedrus, and Symposium - are at least strongly suggestive of the soteriological beliefs of the that cult.

It is really not difficult to interpret the Analogy of the Cave as an analogy from ignorance (avidya in the Indian texts) to philosophical enlightenment although as always Plato's dialogues contain a strong rationalistic element which was not so pronounced in Eastern wisdom teachings. -

The Mind-Created WorldConsciousness IS part of the world at large. If consciousness is immaterial, then the world includes this immaterial sort of thing. — Relativist

The world contains no immaterial things, according to materialism. An 'immaterial thing' is an oxymoronic expression.

The difficulty of devising a naturalistic account of the nature of consciousness is precisely the subject of David Chalmers' 'hard problem of consciousness', the essence of which is that no objective description can truly depict the nature first person experience (ref). There are many active threads on that topic, but suffice to say here, the issue is again one of perspective. Consciousness is not an objective phenomenon, because it is that to which phenomena appear - it is not itself among phenomena. Mind, as such, is never an object in the sense that all of the objects sorrounding you are, including the screen you're reading this from. Husserl's point is precisely that the attempt to 'naturalise' consciousness as an object on the same ontological plane as other objects is erroneous as a matter of principle. (This is why it is essential for Daniel Dennett that it is eliminated, as there is no conceptual space for it in his materialist framework.)

I just don't understand why you think metaphysical physicalism overvalues the scientific method. — Relativist

It is very clear, although to provide a detailed account would occupy many hundreds of words. I will default to one of the passages I often cite from a critique of philosophical materialism, Thomas Nagel's 2012 book Mind and Cosmos:

The modern mind-body problem arose out of the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century, as a direct result of the concept of objective physical reality that drove that revolution. Galileo and Descartes made the crucial conceptual division by proposing that physical science should provide a mathematically precise quantitative description of an external reality extended in space and time, a description limited to spatiotemporal primary qualities such as shape, size, and motion, and to laws governing the relations among them. Subjective appearances, on the other hand -- how this physical world appears to human perception -- were assigned to the mind, and the secondary qualities like color, sound, and smell were to be analyzed relationally, in terms of the power of physical things, acting on the senses, to produce those appearances in the minds of observers. It was essential to leave out or subtract subjective appearances and the human mind -- as well as human intentions and purposes -- from the physical world in order to permit this powerful but austere spatiotemporal conception of objective physical reality to develop.

This is a very succinct statement of a very broad issue which is the subject of many volumes of commentary. But suffice to say this provides the background assumed by physicalism, a background in which Descartes' 'res cogitans' is deprecated and naturalistic explanations sought solely in terms of 'res extensia' or extended matter, which is manipulable and measurable in a way that 'mind' could never be. This is why physics is paradigmatic for physicalism. It is this, which Husserl's critique of naturalism has in its sights.

If there is more to existence than what science can possibly discover or extrapolate, how then can it be discovered? — Relativist

It was at this point last night (in my time zone) that I thought I should chuck it in, on the basis that we're 'talking past' one another. But in the light of day, I will try and compose a response.

In his history of philosophy, Frederick Copleson observes that due to the outstanding achievements and presence of science and technology, that the temper of 20th century philosophy:

The immense growth of empirical science, and the great and tangible benefits brought to civilisation by applied science, have given to science that degree of prestige which it enjoys, a prestige, which far outweighs philosophy and still more theology; and that this prestige of science, by creating the impression that all that can be known, can be known by means of science, has created an atmosphere or metal climate which is reflected in logical positivism. Once, philosophy was regarded as the ‘handmaiden of theology’. Now it has tended to become the ‘handmaiden of science’. As all that can be known can be known by means of science, what is more reasonable than that the philosopher should devote herself to an analysis of the meaning of certain terms used by scientists and an inquiry into the presuppositions of scientific method. .... As science does not come across God in its investigations, and, indeed, as it cannot come across God, since God is, ex hypothesi, incapable of being an object of investigation by the methods of science, the philosopher will also not take God into account. — A History of Philosophy, Vol 11, F. Copleston

Although Armstrong would not describe himself as a logical positivist, I still think this description fairly depicts Armstrong's philosophical perspective.

So the point of all this is as follows: both Kantian idealism, and Husserl's phenomenology, are concerned, not with the objects of knowledge, as discovered by natural science, but with the nature of knowing, from a first-person perspective. So it's not as if they have access to some vast repository of information not known to science, but they are occupied with different kinds of issues than are the sciences. However it's true from the rather 'scientistic' perspective of materialist philosophy of mind, those issues may well be invisible to science, hence not considered suitable subjects of investigation (although they are very much on the agenda for philosophers of science such as Thomas Kuhn and Michael Polanyi.)

I believe I've stayed faithful to this (structural realism) approach in all my replies to you. — Relativist

I wouldn't doubt that, but it also has the effect of interpreting the various materials and sources I'm presenting against that perspective, which is why I think we're 'talking past' one another. However, reviewing that SEP source on Structural Realism, I do notice a paragraph on Kantian ESR which might be congenial to my overall outlook (although I haven't absorbed it yet.)

In any case, the crucial point is the perspectival distinction between idealist and phenonenological stances, and the 'objectivist' stance of Armstrong et al. I hope the foregoing has brought that into a sharper focus. -

The Mind-Created World"consciousness is precisely the reason why there was a world there for us in the first place." - what's the basis for this assertion? — Relativist

You may recall Descartes’ famous meditation, cogito ergo sum. This takes the reality of the thinking subject as apodictic, i.e. cannot plausibly be denied. One of Husserl’s books is Cartesian Meditations, and I think the influence is clear.

(Armstrong) explicitly stated that he believed spacetime comprises the totality of existence, that it is governed by laws of nature, and that physics is concerned with discovering what these are — Relativist

Which is naturalism or physicalism in a nutshell. I do understand that.

If there is more to existence than what science can possibly discover or extrapolate, how then can it be discovered? — Relativist

I think we’ve gone as far as we can go. Thank you for your comments and especially for your evenness of tone. -

The Mind-Created WorldFurther, the error has not prevented science from learning more precise truths- such as a more precise understanding of space and time. — Relativist

I will note here my conviction that time has an inextricably subjective element, which is a specific example of the more general observation in the OP, that perspective is an irreducible element of what we perceive as external reality. There’s an interesting Aeon essay on this point, about Henri Bergson and Albert Einstein’s meeting and debate about the nature of time, n Paris, 1922:

Bergson insisted that duration proper cannot be measured. To measure something – such as volume, length, pressure, weight, speed or temperature – we need to stipulate the unit of measurement in terms of a standard. For example, the standard metre was once stipulated to be the length of a particular 100-centimetre-long platinum bar kept in Paris. It is now defined by an atomic clock measuring the length of a path of light travelling in a vacuum over an extremely short time interval. In both cases, the standard metre is a measurement of length that itself has a length. The standard unit exemplifies the property it measures.

In Time and Free Will, Bergson argued that this procedure would not work for duration. For duration to be measured by a clock, the clock itself must have duration. It must exemplify the property it is supposed to measure. To examine the measurements involved in clock time, Bergson considers an oscillating pendulum, moving back and forth. At each moment, the pendulum occupies a different position in space, like the points on a line or the moving hands on a clockface. In the case of a clock, the current state – the current time – is what we call ‘now’. Each successive ‘now’ of the clock contains nothing of the past because each moment, each unit, is separate and distinct. But this is not how we experience time. Instead, we hold these separate moments together in our memory. We unify them. A physical clock measures a succession of moments, but only experiencing duration allows us to recognise these seemingly separate moments as a succession. Clocks don’t measure time; we do. This is why Bergson believed that clock time presupposes lived time. — Evan Thompson

Bergson’s critique aligns with Kant in suggesting that time is not merely a succession of isolated moments that can be objectively measured, but a continuous and subjective flow that we actively synthesize through consciousness. This synthesis is what lets us experience time as duration, not just as sequential units. It is our awareness of the duration between points in time that is itself time. There is no time outside that awareness.

By this account, Bergson is challenging Einstein’s emphasis on clock-based measurement, pointing to the irreducibility of subjective experience in understanding time’s nature. Kant’s notion of time as an a priori intuition parallels this because he saw time as essential to organizing our experiences into coherent sequences. It’s not a feature of objects themselves but rather of our way of perceiving them—a precondition that shapes experience.

This highlights how understanding “what exists” inevitably involves interpreting it through something that only a perspective can provide. In both Kant and Bergson’s views, the subjective experience of time is foundational, suggesting that any scientific or philosophical statement about existence must, knowingly or not, rely on this element of lived experience. -

The Mind-Created WorldConstructive Empiricism seems to me to go to far, by denying that science tells us anything about reality. — Relativist

I don't know if it does that. The term 'anti-realist' often gives the impression of someone who denies the reality of science or regards scientific findings as somehow illusory or insubstantial. This isn’t what van Fraassen advocates at all. Instead, he’s deeply committed to the empirical success and practical validity of science but questions whether we should interpret scientific theories as giving us a literal account of an objective, mind-independent reality. At issue is the nature of the fundamental constituents of reality and whether they are physical, as physicalism claims.

Another basic point in this context is the distinction between reality, as the aggregate or sum total of observable phenomena and the objects of scientific analysis, and being, as a description of the existence as experienced by human beings. This is where I think physicalism over-values scientific method, for which physicalism may be an effective heuristic while being descriptively accurate within its scope. But many of the questions of philosophy may not be amendable to scientific analysis. Unless you're a positivist, that doesn't make them meaningless.

we should not accept standard scientific realism, which asserts that the nature of the unobservable objects that cause the phenomena we observe is correctly described by our best theories. — Relativist

which also implies distance from physicalism. -

Visualization/Understanding or Obscurantist Elitism?A few by the renowned idealist Berkeley seem to be rather relevant here. — substantivalism

Do you know that in addition to being described as idealist, Berkeley is overall categorised with the British Empiricists. Why? Like Locke and Hume, Berkeley rejected the notion of innate ideas and emphasizes that all knowledge ultimately comes from sensory experience. For Berkeley, our knowledge of the world is grounded in perceptions—ideas that come directly from sensory experience. He rejects the rationalist view that reason alone provides access to knowledge independent of experience. Even though he disagrees with Locke on the existence of a material substance, he still accepts Locke’s methodology of starting from sensory impressions rather than innate concepts or principles. He adopts a systematic, experience-based approach, where sensory data as the fundamental "stuff" of his philosophy, even if he arrives at different metaphysical conclusions than do Locke or Hume.

His arguments against material substance are essentially aimed at pushing empiricism to its logical conclusion: if knowledge depends entirely on sensory experience, then the notion of a material world that exists independently of perception is, he argues, meaningless. So, while Berkeley’s conclusion—that reality consists only of minds and ideas—diverges from Locke’s or Hume’s, his reliance on sensory experience as the foundation of knowledge places him within the empiricist tradition.

You can see how this is one source of what was to become positivism in subsequent periods. -

The Empty Suitcase: Physicalism vs Methodological NaturalismThe fact that some constructs in science don't represent real physical objects doesn't imply anything about physicalism vs. alternatives. — Apustimelogist

...the inherent difficulties of the materialist theory of the atom, which had become apparent even in the ancient discussions about smallest particles, have also appeared very clearly in the development of physics during the present century.

This difficulty relates to the question whether the smallest units are ordinary physical objects, whether they exist in the same way as stones or flowers. Here, the development of quantum theory...has created a complete change in the situation. The mathematically-formulated laws of quantum theory show clearly that our ordinary intuitive concepts (of existence) cannot be unambiguously applied to the smallest particles. All the words or concepts we use to describe ordinary physical objects, such as position, velocity, color, size, and so on, become indefinite and problematic if we try to use them of elementary particles. I cannot enter here into the details of this problem, which has been discussed so frequently in recent years. But it is important to realize that, while the behavior of the smallest particles cannot be unambiguously described in ordinary language, the language of mathematics is still adequate for a clear-cut account of what is going on.

During the coming years, the high-energy accelerators will bring to light many further interesting details about the behavior of elementary particles. But I am inclined to think that the answer just considered to the old philosophical problems will turn out to be final. If this is so, does this answer confirm the views of Democritus or Plato?

I think that on this point modern physics has definitely decided for Plato. For the smallest units of matter are, in fact, not physical objects in the ordinary sense of the word; they are forms, structures or — in Plato's sense — Ideas, which can be unambiguously spoken of only in the language of mathematics. — Werner Heisenberg, The Debate between Plato and Democritus (i.e. between idealism and materialism) -

The Mind-Created World“If you’re moved by something, it doesn’t need explaining.

If you’re not, no explanation will move you.”

—Federico Fellini -

The Mind-Created WorldThanks, Javra. Very much in keeping with the OP.

I was going to suggest to @Relativist whether he'd ever encountered 'constructive empiricism', associated with Bas Van Fraasen.

Constructive empiricism is a philosophical view that science aims to produce theories that are empirically adequate, rather than true. It was developed by the 20th-century Canadian philosopher Bas van Fraassen and is presented most systematically in his 1980 work The Scientific Image.

Constructive empiricism differs from scientific realism, which holds that science aims to provide a literally true story of the world. Constructive empiricists believe that science aims for truth about observable aspects of the world, but not unobservable aspects. They also believe that accepting a scientific theory involves only the belief that it is empirically adequate. — AI Overview

I think this is a framework which is not antagonistic to science while leaving the question of the ultimate nature of reality an open one. -

Existential Self-AwarenessWe have an ego because we are born (in the physical sense). — schopenhauer1

I'm sure the Buddhas understand that. Escaping enculturation is the reason Buddhism started as a renunciate movement (one of many in that culture). -

Existential Self-AwarenessRight. To draw on an element of the current philosophical lexicon, perhaps 'the Buddhist way' is to learn to deconstruct this sense of the alienated self by seeing through the process that drives it - not in an abstract theoretical sense, but in real time (another bit of modern jargon)

Through the round of many births I roamed

without reward,

without rest,

seeking the house-builder.

Painful is birth

again & again.

House-builder, you're seen!

You will not build a house again.

All your rafters broken,

the ridge pole destroyed,

gone to the Unformed, the mind

has come to the end of craving. — DhP 153-4 -

The Mind-Created WorldIt sounds like I had it right: you think physicalism should be rejected if physics doesn't have a complete, verifiable description of reality. — Relativist

That physicalism should be rejected, if the thesis is that 'everything is ultimately physical' while what is physical can't be defined.

Armstrong's model is consistent with what we do know, so it's not falsified. — Relativist

If it hasn't been falsified by quantum physics, it's not falsifiable. So again, it appeals to science as a model of philosophical authority, but only when it suits.

I posted this comment some days ago, do you think it has any bearing on the argument?

In contrast to the outlook of naturalism, Husserl believed all knowledge, all science, all rationality depended on conscious acts, acts which cannot be properly understood from within the natural outlook at all. Consciousness should not be viewed naturalistically as part of the world at all, since consciousness is precisely the reason why there was a world there for us in the first place. For Husserl it is not that consciousness creates the world in any ontological sense—this would be a subjective idealism, itself a consequence of a certain naturalising tendency whereby consciousness is cause and the world its effect—but rather that the world is opened up, made meaningful, or disclosed through consciousness. The world is inconceivable apart from consciousness. Treating consciousness as part of the world, reifying consciousness, is precisely to ignore consciousness’s foundational, disclosive role. For this reason, all natural science is naive about its point of departure, for Husserl (PRS 85; Hua XXV 13). Since consciousness is presupposed in all science and knowledge, then the proper approach to the study of consciousness itself must be a transcendental one—one which, in Kantian terms, focuses on the conditions for the possibility of knowledge. — Routledge Introduction to Phenomenology, p144

Do you see the point of this criticism of philosophical naturalism? Because, if you don't, then I think I'll call it a day. -

The Mind-Created WorldIt seems uncontroversial to stipulate that the objects of our ordinary experiences are physical. It seems most reasonable to treat the component parts of physical things as also physical, all the way down to whatever is fundamental. — Relativist

There's a strong component of common sense realism in it, buttressed by the polemical and rhetorical skills developed by centuries of philosophical argument.

what we regard as the physical world is “physical” to us precisely in the sense that it acts in opposition to our will and constrains our actions. The aspect of the universe that resists our push and demands muscular effort on our part is what we consider to be “physical”. On the other hand, since sensation and thought don’t require overcoming any physical resistance, we consider them to be outside of material reality. — Pinter, Charles. Mind and the Cosmic Order: How the Mind Creates the Features & Structure of All Things, and Why this Insight Transforms Physics (p6).

That’s physicalism in a nutshell.

A "wave function" is a mathematical abstraction. I see no good reason to think abstractions are ontological. So I infer that a wave function is descriptive of something that exists. — Relativist

It isn't so easily dismissed. The ontology of the wave function in quantum physics is one of the outstanding problems of philosophy of science. Realists argue that the wave function represents something real in the world, while instrumentalists may view it as merely a predictive tool without deeper ontological significance. Treating it as only an abstraction is one option but it is far from universally accepted. The point is, claiming that everything that exists is physical becomes problematic if we can’t definitively say what kind of existence the wave function has, as in quantum mechanics, the wave function is central to predicting physical phenomena. If we take its predictive power seriously, it’s hard to ignore the question of its ontological status without leaving an unresolved gap in the theory.

I may misunderstand, but it sounds also bit like you're suggesting that we should reject physicalism if physics doesn't have a complete, verifiable description of reality. — Relativist

As I said before, as a materialist, D M Armstrong believes that science is paradigmatic for philosophy proper. So you can't have your cake and eat it too - if physics indeed suggests that the nature of the physical eludes precise definition, then so much for appealing to science as a model for philosophy!

I acknowledge that our descriptions (and understandings) are grounded in our perspective, but we have the capacity to correct for that. — Relativist

Perspective is not the same as bias.

I'd like to know if there are good reasons to think I'm deluding myself with what I believe about the world. — Relativist

I wouldn't put it in personal or pejorative terms, but I do believe that philosophical and/or scientific materialism is an erroneous philosophical view. -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)I love that Trump is having conniptions because A POLL puts him behind in Iowa. One poll. Sure, an influential and well-regarded poll, but all his staffers are running around trying to appease the Emperor and putting out press releases that that pollster is wrong. Imagine the scene if he ACTUALLY loses (as I hope and believe.) There’ll be more than ketchup on the walls. Imagine the staff. (“I wouldn’t change places with Ed Exley now for all the whisky in Ireland” ~ LA Confidential.)

-

“Distinctively Logical Explanations”: Can thought explain being?I think so too but there doesn’t seem much awareness of it, let alone consensus.

As for the relationship of time and motion, that seems obviously implied by the equation of space and time in relativity. But neither space nor time are self-existent, so to speak. -

The Mind-Created WorldIt is false only if there exists something non-physical. — Relativist

But you say:

No interpretation of QM is verifiably true, but it's a near certainty that reality actually exhibits the predictible law-like behavior that we observe. — Relativist

Sure it does. But what about this requires that the fundamental constituents are actually physical? What does 'physical' mean, when the nature of the so-called fundamental particles is ambiguous, as has been discussed? It's entirely plausible that 'physical' is a concept only applicable to composite objects, but not to their fundamental constituents. After all Neils Bohr said 'Everything we call real is made of things that cannot be regarded as real'. You could substitute 'physical' for 'real' in that sentence and it would still parse correctly.

And as for something non-physical, the wavefunction Ψ is an ideal candidate:

There is a crucial difference between the wave effect in the double-slit experiment and physical waves. In classical wave systems, such as ripples on water, the frequency — the number of wave peaks passing a point per second — determines the pattern and behavior of the wave. We might expect to equate the rate of emission (how often electrons are fired) with the frequency of a classical wave. But in quantum mechanics, this analogy breaks down, as particles can be emitted one at a time — and yet the interference pattern still forms. There is no equivalent in classical physics for a “one particle at a time” emission in a medium like water.

So the interference pattern arises not because the particles are behaving as classical waves, but because the probability wavefunction ψ describes where at any given point in time, any individual particle is likely to register. So it is wave-like, but not actually a wave, in that the pattern is not due to the proximity of particles to each other or their interaction, as is the case with physical waves. Consequently, the interference pattern emerges over time, irrespective of the rate at which particles are emitted, because it is tied to the wave-like form of the probability distribution, not to a physical wave passing through space. This is the key difference that separates the quantum interference pattern from physical wave phenomenon. This is what I describe as ‘the timeless wave of quantum physics’. — The Timeless Wave -

Visualization/Understanding or Obscurantist Elitism?If I had a machine that could pump out meaningful, experimentally under-determined, and intelligible philosophical statements/systems by the thousands is indulging in the debate or discussion around them a proper place of a rational individual, a modern philosopher, or a practicing physicist? Or should such speculation always be avoided with extreme prejudice? — substantivalism

There is no such machine, because meaning comes from what matters, and nothing matters to a machine. It has no skin in the game, so to speak (only natural, as it has no actual skin).

Ever happened upon Sabine Hossenfelder's book Lost in Math? There might be some commonality between what you're asking and that book. -

Existential Self-AwarenessSo existence is basically a "suffering", in terms of this definition being the temporariness of satisfied states, and the initial lack that we feel, an incompleteness that is basically never-ending. — schopenhauer1

Right. As you say, similar to Schopenhauer, where he converges with Buddhist and Hindu ideas.

But the cruel part is the "fooling" aspect. As the human animal, unlike mere instinct or simpler forms of experience that other animals exhibit, is that we make "goals" for ourselves. And those goals often are thwarted, and we are disappointed, or when they are reached, they are but temporary, and thus "the vanity" of Ecclesiastes. And throughout all this will-thwarting-temporary satiation, we have the anxieties and physical ailments of social and physical harms. We are self-aware, we know this. Yet what biases delude us? — schopenhauer1

But isn't it an inevitable consequence of being human, in a way that it is not for animals? Hereunder an excerpt from a powerful essay by another contemporary Buddhist, Zoketsu Norman Fischer, which was written as a reflection on 9/11 and the religious rationale for terrorism (although that particular aspect is not relevant at this point). I quote it, because I think it's a plausible, existential account of the source of the angst for self-aware beings such as ourselves.

In his book The Theory of Religion, translated by Robert Hurley (Zone Books, 1992), Georges Bataille analyzes the arising of human consciousness as it emerges out of animal consciousness and shows how religious sensibility necessarily develops from this. His argument goes like this:

The animal world is a world of pure being, a world of immediacy and immanence. The animal soul is like “water in water,” seamlessly connected to all that surrounds it, so that there is no sense of self or other, of time, of space, of being or not being. This utopian (to human sensibility, which has such alienating notions) Shangri-La or Eden actually isn’t that because it is characterized at all points by what we’d call violence. Animals, that is, eat and are eaten. For them killing and being killed is the norm; and there isn’t any meaning to such a thing, or anything that we would call fear; there’s no concept of killing or being killed. There’s only being, immediacy, “isness.” Animals don’t have any need for religion; they already are that, already transcend life and death, being and nonbeing, self and other, in their very living, which is utterly pure.

Bataille sees human consciousness beginning with the making of the first tool, the first “thing” that isn’t a pure being, intrinsic in its value and inseparable from all of being. A tool is a separable, useful, intentionally made thing; it can be possessed, and it serves a purpose. It can be altered to suit that purpose. It is instrumental, defined by its use. The tool is the first instance of the “not-I,” and with its advent there is now the beginning of a world of objects, a “thing” world. Little by little out of this comes a way of thinking and acting within thingness (language), and then once this plane of thingness is established, more and more gets placed upon it—other objects, plants, animals, other people, one’s self, a world. Now there is self and other—and then, paradoxically, self becomes other to itself, alienated not only from the rest of the projected world of things, but from itself, which it must perceive as a thing, a possession. This constellation of an alienated self is a double-edged sword: seeing the self as a thing, the self can for the first time know itself and so find a closeness to itself; prior to this, there isn’t any self so there is nothing to be known or not known. But the creation of my me, though it gives me for the first time myself as a friend, also rips me out of the world and puts me out on a limb on my own. Interestingly, and quite logically, this development of human consciousness coincides with a deepening of the human relationship to the animal world, which opens up to the human mind now as a depth, a mystery. Humans are that depth, because humans are animals, know this and feel it to be so, and yet also not so; humans long for union with the animal world of immediacy, yet know they are separate from it. Also they are terrified of it, for to reenter that world would be a loss of the self; it would literally be the end of me as I know me.

In the midst of this essential human loneliness and perplexity, which is almost unbearable, religion appears. It intuits and imagines the ancient world of oneness, of which there is still a powerful primordial memory, and calls it the sacred. This is the invisible world, world of spirit, world of the gods, or of God. It is inexorably opposed to, defined as the opposite of, the world of things, the profane world of the body, of instrumentality, a world of separation, the fallen world. Religion’s purpose then is to bring us back to the lost world of intimacy, and all its rites, rituals, and activities are created to this end. We want this, and need it, as sure as we need food and shelter; and yet it is also terrifying. All religions have known and been based squarely on this sense of terrible necessity.

Of course, much more need be said, and this is only an excerpt, but I think it frames the issue well. -

Existential Self-Awareness'Axiology, derived from the Greek words “axios” (value) and “logos” (study), is the philosophical exploration of value. It encompasses the examination of what is valuable and why, exploring the nature of values, their hierarchy, and their relationship with individuals, societies, and cultures. Axiology encompasses both ethics (the study of moral values) and aesthetics (the study of beauty and taste).'

So, in the case of Buddhism, the basis of value - the fundamental axiology, if you like - is the ubiquitity and unavoidable nature of suffering, old age and death. Its formulaic exposition is always given in those terms - you will loose what you love, be beset by things you don't like, suffer, and die. Those are given facts of existence. Liberation from that (nibbana, Nirvāṇa) is the extinction of the factors that drive continued existence in the mode of existence subject to these conditions. -

The Mind-Created WorldBut you're making an error if you think materialism requires these scientific models to be correct depictions of reality. The metaphysics does not depend on these models to correspond to reality. — Relativist

So, what does it depend on, then? -

Existential Self-AwarenessIn a Buddhist sense, you might agree with Schopenhauer that Buddhist practice is what the self-aware animal must look to. — schopenhauer1

Well, look at the mythological description of the origin of Siddhartha's quest. He comes of age sorrounded by luxury and shielded from misfortune and suffering. But then he undertakes excursions outside the palace walls with his trusty charioteer, and sees the 'four sights'. Which four sights? An old man, bent over and walking very slowly with a stick. A sick man, in a state of distress. A corpse being escorted to the burning ghats. And finally a renunciate (sramana) with a serene countenance. This set the curriculum, so to speak, for Siddharta's quest, culminating in his realisation as the Buddha, by which he was forever liberated from the round of saṃsāra - sickness, old age and death.

As to the relationship of humans and animals - as is well-known Buddhism is generally a humane religion, never having practiced animal sacrifice (unlike Vedic brahmanism.) Nevertheless Buddhists do not agree that humans are on the same plane of existence as animals, as humans have sufficient intelligence to hear the teaching and follow it. (See David Loy, Are Humans Special?, discussing Buddhist views on the significance of human life. Although I'm well aware that regarding human life as somehow different or 'special' is nowadays a very politically-incorrect stance, which I'm reminded of anytime I post about it.) -

The Mind-Created WorldNo, but they're also not understandable outside the scientific context within which they were discovered.

— Wayfarer

I don't understand why you say that. Please elaborate. — Relativist

The question was about elementary particles and genes. These are part of scientific models.

It is well known that the nature of the existence of former, in particular, is rather ambiguous, to say the least. Although I don't want to divert this thread too far in this direction, this is where the Copenhagen interpretation of physics is relevant. This says that physics does not reveal what nature is in itself (or herself, some would say) but as how she appears to our methods of questioning. So these 'elementary particles' are not mind-independent in that sense - which is the implication of the observer problem. They only appear to be particles when subjected to a specific kind of experimental setup. This is part of why there is a tendency towards philosophical idealism in modern physics (e.g. Henry Stapp, John Wheeler, Werner Heisenberg, Bernard D'Espagnat, Shimon Malin, can all be said to advocate for one or another form of philosophical idealism. The latter's book is called Nature Loves to Hide.)

As for genes, and whether these comprise a fundamental explanatory unit, again, the emergence of epigenetics has given rise to an understanding that genes themselves are context-dependent. That is not downplaying the significance of the discovery of genes (or quantum theory, for that matter) but the role they are both assigned by physicalism as being ontologically primary or fundamental.

If you don't believe we can know truths about the world, that seems more significant than whether or not the mind can be adequately accounted for through physicalism. I don't see how you could propose a superior alternative with such a background assumption. — Relativist

I don't know how you could come to that conclusion. We know all manner of things about the world. I'm not denying that scientific knowledge is efficacious. What I'm questioning is the metaphysics of materialism, which posits that 'Elementary particles, moments in time, genes, the brain – all these things are assumed to be fundamentally real. By contrast, experience, awareness and consciousness are taken to be secondary' (The Blind Spot). Armstrong's physicalist philosophy would maintain that exact view, would it not? That the mind is 'the product of the brain'? What else could 'materialist theory of mind mean? And I think it can be questioned, without saying that nobody knows anything about the world.

I think I can see the point you're having difficulty with (and please don't take this to be condescending.) Philosophical idealism is nearly always understood as the view that 'the world only exists in the mind'. I think that is how you're reading what I am saying, which is why you believe that for me to acknowledge the reality of objective facts will undermine idealism. But what I'm arguing is that this is a misreprentation of what is true about idealism.

To get a bit technical, it's the difference between Berkeley's idealism, and Kant's. Kant acknowledges the empirical veracity of scientific hypotheses (empirical realism). After all, he was a polymath who devised a theory of nebular formation, which, adapted by LaPlace, is still considered current. But transcendental idealism still maintains that in a fundamental sense, the mind provides the intuitions of time and space, within which all such empirical judgements are made. I know it's a really hard distinction to get. Bryan Magee says 'We have to raise almost impossibly deep levels of presupposition in our own thinking and imagination to the level of self-consciousness before we are able to achieve a critical awareness of all our realistic assumptions, and thus achieve an understanding of transcendental idealism which is untainted by them. This, of course, is one of the explanations for the almost unfathomably deep counter-intuitiveness of transcendental idealism, and also for the general notion of 'depth' with which people associate Kantian and post-Kantian philosophy. Something akin to it is the reason for much of the prolonged, self-disciplined meditation involved in a number of Eastern religious practices.'

If what is addressed by the term “reality” (I presume physical reality which, in a nutshell, is that actuality (or set of actualities) which affects all minds in equal manners irrespective of what individual minds might believe or else interpret, etc.) will itself be contingent on the occurrence of all minds which simultaneously exist—and, maybe needless to add, if the position of solipsism is … utterly false—then the following will necessarily hold: reality can only be independent of any one individual mind. As it is will be independent of any particular cohort of minds—just as long as this cohort is not taken to be that of “all minds that occur in the cosmos”. — javra

I have read about Bernardo Kastrup's idea of 'mind at large'. At first I was sceptical of it but I've come around to it, if it is understood simply as 'some mind'. Not yours or mine, or anyone's in particular but as a genre. -

“Distinctively Logical Explanations”: Can thought explain being?’m inclined to suggest Bergson was Kantian, but the article doesn’t support me, so I better not. — Mww

Maybe it does. Consider this paragraph:

In Time and Free Will, Bergson argued that this procedure would not work for duration. For duration to be measured by a clock, the clock itself must have duration. It must exemplify the property it is supposed to measure. To examine the measurements involved in clock time, Bergson considers an oscillating pendulum, moving back and forth. At each moment, the pendulum occupies a different position in space, like the points on a line or the moving hands on a clockface. In the case of a clock, the current state – the current time – is what we call ‘now’. Each successive ‘now’ of the clock contains nothing of the past because each moment, each unit, is separate and distinct. But this is not how we experience time. Instead, we hold these separate moments together in our memory. We unify them. A physical clock measures a succession of moments, but only experiencing duration allows us to recognise these seemingly separate moments as a succession. Clocks don’t measure time; we do. This is why Bergson believed that clock time presupposes lived time.

This provides a connection between Bergson's concept of 'lived time' (or duration) and Kant’s idea of time as a form of intuition—a foundational structure through which we experience and organize reality. Bergson's critique aligns with Kant in suggesting that time is not merely a succession of isolated moments that can be objectively measured, but a continuous and subjective flow that we actively synthesize through consciousness. This synthesis is what lets us experience time as duration, not just as sequential units.

In this account, Bergson is challenging Einstein’s emphasis on clock-based measurement, pointing to the irreducibility of subjective experience in understanding time’s nature. Kant’s notion of time as an a priori intuition parallels this because he saw time as essential to organizing our experiences into coherent sequences. It’s not a feature of objects themselves but rather of our way of perceiving them—a precondition that shapes experience.

This is connected to why I argue for the 'primacy of perspective'. Without an observing mind that strings things together, there is no time as such. And despite Einstein's undoubted genius, he could never let go his realist convictions. I see that as a philosophical shortcoming. -

The Mind-Created WorldI asked you to say explicitly what you thought was wrong with Husserl's criticism of naturalism, which you didn't do. How about this excerpt from Bryan Magee's 'Schopenhauer's Philosophy'? You will notice that it opens with the very challenge you have just given:

Everyone knows that the earth, and a fortiori the universe, existed for a long time before there were any living beings, and therefore any perceiving subjects. But according to Kant ... that is impossible.'

Schopenhauer's defence of Kant on this score was [that] the objector has not understood to the very bottom the Kantian demonstration that time is one of the forms of our sensibility. The earth, say, as it was before there was life, is a field of empirical enquiry in which we have come to know a great deal; its reality is no more being denied than is the reality of perceived objects in the same room.

The point is, the whole of the empirical world in space and time is the creation of our understanding, which apprehends all the objects of empirical knowledge within it as being in some part of that space and at some part of that time: and this is as true of the earth before there was life as it is of the pen I am now holding a few inches in front of my face and seeing slightly out of focus as it moves across the paper.

This, incidentally, illustrates a difficulty in the way of understanding which transcendental idealism has permanently to contend with: the assumptions of 'the inborn realism which arises from the original disposition of the intellect' enter unawares into the way in which the statements of transcendental idealism are understood.

Such realistic assumptions so pervade our normal use of concepts that the claims of transcendental idealism disclose their own non-absurdity only after difficult consideration, whereas criticisms of them at first appear cogent which on examination are seen to rest on confusion. We have to raise almost impossibly deep levels of presupposition in our own thinking and imagination to the level of self-consciousness before we are able to achieve a critical awareness of all our realistic assumptions, and thus achieve an understanding of transcendental idealism which is untainted by them. — Bryan Magee, Schopenhauer's Philosophy

If you think this is wrong, say why. -

The Mind-Created WorldI don't think this is a hard fact to grasp, but surprisingly you seem to have much difficulty understanding (or is it perhaps accepting?) it. — Janus

If you address the actual argument, I will respond. -

The Mind-Created WorldDo you deny that science can tell us much about the real, mind-independent world? Are elementary particles and genes pure fiction? — Relativist

No, but they're also not understandable outside the scientific context within which they were discovered.

I've said, I don't deny the reality of there being an objective world, but that on a deeper level, it is not truly mind-independent. Which is another way of saying objectivity cannot be absolute.

Why does this matter? — Relativist

As for whether you're defending physicalism, the link to this discussion was made from this post in another thread in which you claimed to be 'representing David Armstrong's metaphysics'. I see the above arguments as a challenge to Armstrong's metaphysics. As I'm opposing Armstrong's metaphysics, this is why I think it matters.

For me the idea of explaining the nature of the subject in physicalist terms is simply, under a certain conception of the nature of the subject, a misunderstanding of what could be possible in attempting to combine incommensurable paradigms of thought. — Janus

You put a lot of effort into disagreeing with something you actually don't disagree with. -

The Mind-Created WorldWe are already there in those subjects as the investigator, but we don't appear in the subject itself just as the eye does not appear in the visual field. — Janus

True - but not trivial. That is an insight I claim you will never find called out in mainstream Anglo philosophy. It challenges the point of physicalist philosophy of mind, which is to explain the nature of the subject in objective physical terms.

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum