-

Where is AI heading?Anyway, it went real well with no significant catastrophes the day of. — noAxioms

Glad is was such a happy occasion!

Likely some more than others. -

The 'hard problem of consciousness'Ok, Husserl might not seem to be a dualist, but the assumption that consciousness is immaterial in the sense that it never appears as an object in a world of objects, implies an epistemological dualism, and the hard problem reappears. For if consciousness is immaterial, then it seems we have no way of knowing what it's like to be another observer, or how immaterial experiences arise in a material world. — jkop

Well, that's true! The whole point of the argument is to throw into stark relief a fundamental gap in the generally-accepted physical account of the world. It has been said many times that in the transition from the medieval geocentric universe to modern cosmology, that the world became concieved in terms which make life itself, and human life in particular, a kind of anomaly* (per Stephen Hawking's often-quoted quip that we're a kind of chemical scum on a medium-sized planet, or Steven Weinberg's remark that 'the more the universe seems comprehensible the more it seems pointless'.)

The point is, though, that the objective judgement of the miniscule dimensions of human life against the vast background of modern cosmology is existence 'viewed from the outside', so to speak. It is made from a perspective in which we ourselves are treated as objects. And that is a direct implication of modern objective science in which the measurable attributes of objects (mass, volume, number, velocity and so on) are declared fundamental and the appearance, colour, etc assigned to secondary or subjective status. It is a worldview tailor-made to exclude the subject to as to arrive at the putative, scientific 'view from nowhere'. And I think that is all the hard problem argument shows up - and it does so quite effectively (one reason why at any given time there are a number of threads discussing it.)

For idealists for whom everything is consciousness, the hard problem does not arise from a metaphysical or epistemological wedge. Likewise, it doesn't arise for direct realists under the assumption that we see objects directly — jkop

I consider myself idealist, but I also believe that all the objects I interact with are real objects. They're not constituted by mind, but on the other hand, they only appear and are meaningful within experience. That is what I mean by 'idealism', although perhaps it is closer to phenomenology. Whereas I have the sense that when you say 'idealism', you believe that it posits something called 'mind' which is constitutive of reality in the same way that 'matter' is for materialism. But that, I would suggest, is what Whitehead meant by the sense of misplaced concreteness, or the attribution of reality to abstractions (such as 'mind' and 'matter'). It's a reification.

Which leads to:

For example, a bird observing its environment,, birdwatchers observing the bird, a prison guard observing prisoners, a solo musician observing his own playing, an audience observing the musician, scientists observing their experiments, a thinker observing his own thinking (e.g. indirectly via its effects). — jkop

Splendid observation! This brings up the idea of the 'lebenswelt' or 'umwelt' which is very much part of both phenomenology and embodied cognition. They refer to the 'meaning-world' in which all organisms including humans orient themselves, where 'objects' appear in terms of their use and meaning for that being. Within that context, objects are no longer abstractions, but real and felt elements of lived experience.

Compare this passage from the phenomenologist, Maurice Merleau Ponty:

For the player in action the football field is not an ‘object,’ that is, the ideal term which can give rise to an indefinite multiplicity of perspectival views and remain equivalent under its apparent transformations. It is pervaded with lines of force (the ‘yard lines’; those which demarcate the ‘penalty area’) and articulated in sectors (for example, the ‘openings’between the adversaries) which call for a certain mode of action and which initiate and guide the action as if the player were unaware of it. The field itself is not given to him, but present as the immanent term of his practical intentions; the player becomes one with it and feels the direction of the ‘goal,’for example, just as immediately as the vertical and the horizontal planes of his own body. It would not be sufficient to say that consciousness inhabits this milieu. At this moment consciousness is nothing other than the dialectic of milieu and action. Each maneuver undertaken by the player modifies the character of the field and establishes in it new lines of force in which the action in turn unfolds and is accomplished, again altering the phenomenal field. (Merleau-Ponty, 1942/1963, pp. 168–9, emphasis added) — Quoted in Précis of Mind in Life: Biology, Phenomenology, and the Sciences of Mind, Evan Thompson

Notice that this approach undercuts the tendency to view 'consciousness' (or mind) as an object, state or thing of any kind. This is why the embodied cognition approach provides a solution, or remedy, to the hard problem, by showing up the artificial nature of the division between mind and world which is at its root.

------

*This is the thrust of an early (1955) esssay in the phenomenology of biology by Hans Jonas: The Phenomenon of Life. -

“Distinctively Logical Explanations”: Can thought explain being?Well, I know it's all off-topic for this thread, but that passage you quoted resonated with me.

-

“Distinctively Logical Explanations”: Can thought explain being?Or perhaps indivisible, and that seems to be a bit different. A chicken is indivisible. To divide it is to lose your chicken. — Leontiskos

But notice:

There was consensus among the scholastics on both the convertibility of being and unity, and on the meaning of this ‘unity’ —in all cases, it was taken to mean an entity’s intrinsic indivision or undividedness. — Being without One, by Lucas Carroll, 121-2

This is the principle that animates all living beings, from the most simple up to and including humans. it is why, for instance, all of the cells in a living body develop and differentiate so as to serve the overall purpose of the organism. So the 'one-ness' of individual beings is like a microcosmic instantiation of 'the One'. It is the basis of 'bio-logos' and the reason why Aristotelian biology retains a relevance that his physics does not

For example, the magic of a Monet derives from the artist's deliberate attempt to create a unity out of a set of spatially separate blobs of paint on a canvas. Such a unity exists only in the mind of the observer, not in the world, in that one blob of paint of the canvas has no "knowledge" as to the existence of any other blob of paint on the canvas. Patterns only exist in the mind, not the world.

As patterns don't ontology (sic) exist in the world, but do exist in the mind, to say that patterns in the mind have derived from patterns in the world is a figure of speech rather than the literal truth. — RussellA

But, all organic life displays just the kind of functional unity that a painting does, spontaneously. Those patterns most definitely inhere in the organic world. DNA, for instance.

the neo-logos philosophies might say something like, "If nature has patterns, and our language has patterns, and we are derived from nature, it may be the case that our language is a necessary outcome of a more foundational logic". — schopenhauer1

I am afraid we are not rid of God because we still have faith in grammar. — Nietszche -

The 'hard problem of consciousness'Computers create models of the world. Does this mean that the computer can imagine things? What makes brains so special in that minds arise from them but cannot arise from a computer? Both are physical objects and both are doing similar things in processing (sensory) information. If a physical object like a brain can produce a mind, then why not a computer? — Harry Hindu

Computers operate according to the parameters, programming, and designs created by the scientists who build them. While it's true that large language models can generate unexpected insights based on their training data and algorithms, the key point is that these systems do not understand anything. They process and output information, but it's not until their output is interpreted by a human mind that true understanding occurs.

Additionally, I dispute the idea that the brain is simply a 'physical object.' The brain might appear as a physical object when extracted from a body and examined by a pathologist or neuroscientist. But in its living context, the brain is part of an organism—embodied, encultured, and alive. In that sense, it's not just an object but part of a dynamic, living process that produces consciousness in ways that no computer can replicate. -

The 'hard problem of consciousness'I have quoted your question and my response in this thread as it is offtopic for this one.

-

Quantum Physics and Classical Physics — A Short NoteResponse shifted from here.

↪Gnomon

Generally :up: but watch out for the tendency to reify, 'make into a thing'.

— Wayfarer

Thanks. You have warned me about "reification" before*1. But it seems that most Philosophy-versus- Science arguments, going back to Plato's Idealism, hinge on the Reality (plausibility ; utility ; significance) of abstractions. Are Mathematics and Metaphysics "real" or "ideal"? Regardless of how you categorize them, Ideal or Abstract non-things are very important for philosophical discussions, no?.

Is the Aether, postulated by physicists to explain such ideas as "vacuum energy" real or ideal? Here's what I said about that : "I argue that the metaphysical Aether is immaterial, just like the hypothetical Quantum Vacuum and the Universal Quantum Field. It's not physical or spiritual, but mathematical (statistical) and mental (logical). If Math & Mind are real, so is the statistical sphere of Probability & Potential.". Is "immaterial" the same as non-thing & unreal? Is Math a real thing, or an abstraction in a human mind? Is the Quantum Field*2 a perceivable real thing, or an abstract human concept?

I didn't claim that Aether is an actual physical thing, as some physicists seem to imply*2. Instead, I'm saying that it is the Potential for causal Energy ; which is the Potential for actual Matter*3. So, the philosophical question here seems to be : is Potential to Actual*4 the same as Reification". It seems to "make nothing into a thing". :smile:

*1. Reification means to treat something abstract as if it were a physical thing. For example, you might reify an abstract concept like fear, happiness, or evil.

The process of turning human concepts, actions, processes, relations, and properties into tangible things

___Google AI overview

*2. According to current scientific understanding, quantum fields are considered to be real, existing throughout space and acting as the fundamental building blocks of the universe, with experimental evidence supporting their existence and effects; although they are a theoretical construct, they provide incredibly accurate predictions about the behavior of particles and are considered the best explanation for our physical reality at the subatomic level.

___Google AI overview

Note --- Is "considered to be real" a fact or a belief? Is a "theoretical construct" a real thing, or a reification?

*3. Yes, "energy is potential for matter" means that energy represents the capacity to do work or cause change in matter, essentially acting as a stored potential that can be released to create movement or transformations within matter; this is often described as potential energy, which is energy stored due to an object's position or state, ready to be converted into kinetic energy (motion) when conditions change.

___Google AI overview

*4. In Aristotle's philosophy, potentiality is the capacity of something to develop into a specific state or perform a specific function, while actuality is the realization of that capacity. These concepts are central to understanding change and reality, and helped Aristotle explain how things can change while maintaining their identity.

___Google AI overview — Gnomon

///

Regardless of how you categorize them, Ideal or Abstract non-things are very important for philosophical discussions, no?. — Gnomon

The specific point at issue was the idea that while the wavefunction predicts probabilities, it seems a 'wave without a medium' - to which you mused whether that might be 'aether' of yore. But again, the epistemological interpretations don't posit that the wavefunction is physically real, but a wave-like pattern of likelihoods. The question as to what is the medium then doesn't arise. Isn't that what bothers the realists, like Hawking and Einstein? The fact that the theory can't say what is 'really there'?

is Potential to Actual*4 the same as Reification". It seems to "make nothing into a thing". — Gnomon

My hazy understanding is that the observation or measurement process 'makes manifest' what was previously indeterminate. The issue being, if you ask the question, 'what do you mean "indeterminate"?' then it's an impossible question to answer, as to identify it is to make a determination! (as per above).

In Aristotle's philosophy, potentiality is the capacity of something to develop into a specific state or perform a specific function, while actuality is the realization of that capacity. — Gnomon

I think I've mentioned this article before about how Heisenberg incorporates Aristotle's 'potentia'. (But then, Heisenberg was the most 'Platonist' of the quantum pioneers, he was known to carry around a copy of the Timeaus at University. I posted a copy of one of his talks on Platonism 'The Debate between Plato and Democritus'.)

The issue with reification is a subtle one, but it has to do with the shift to 'objective consciousness' that occured in the transition to the modern period. Perhaps look at this post from another thread.

I think the 'vaccum energy' is something quite different from the wave function and that it is physical, although here are the leading edge of physics there are very difficult questions about whether and in what sense fields are physical. I suppose the answer is, we know they're physical because we have instruments that measure their effects on mattter. (But a question I sometimes ask is, what if there are fields other than electromagnetic, like Sheldrake's Morphic Fields? Many unanswered questions lurk.) -

Logical proof that the hard problem of consciousness is impossible to “solve”This is picturing for literal sight of the ultimate self-referential grabbing. — ucarr

I’m afraid that is word salad. The fact that a hand cannot grasp itself is apodictic.

You're trying to set boundaries for the context of the HPoC debate. — ucarr

Not setting - describing. I don’t accept the Cartesian division but it is a real factor in culture, which the hard problem argument is intended to reveal.

Modern physics, with the backing of QM and the measurement problem, rejects the binary as falsity. — ucarr

You might enjoy a recent essay I have composed on that topic. -

The 'hard problem of consciousness'Right, so instead of substance-dualism you have two orders or perspectives or property-dualism. All the same, when we want to explain how two phenomena are related to each other, yet assume that they are fundamentally different in a way that makes is hard or impossible to understand how they could be related, then the problem might be in the assumption. — jkop

No, it’s not property dualism. The passage I quoted was an example of phenomenology. It doesn’t categorise consciousness as a phenomenon, as phenomena appear to consciousness. -

“Distinctively Logical Explanations”: Can thought explain being?Unum in the same sense as in non-dualism, advaita, non divided.

-

The (possible) Dangers of of AI TechnologyJust machines to make big decisions

Programmed by fellows with compassion and vision

We’ll be clean when their work is done

Eternally free, yes, and eternally young — Donald Fagen, I.G.Y.

I’ll have a listen although I’m already dubious about the premise that people are bad because of ‘bad information’.

Still, many interesting things to say :up: -

Where is AI heading?I now have a new daughter in law, and have attended what we knew would likely be a covid spreader event — noAxioms

Your son’s wedding, then? What a romantic description! -

Logical proof that the hard problem of consciousness is impossible to “solve”Report: RH = RH. — ucarr

I’ll need photographic evidence in this case ;-)

I say that when I make a claim about something, intending by my claim to establish an objective fact, I simultaneously treat that something as an object. — ucarr

Fair point. We could say of someone, ‘she has a brilliant mind’. In that case her mind is indeed an object of conversation. I could say of my own mind that at such and such a time I was in a confused state, in which case my own mind was the subject of the recollection.

You can also use ‘see’ metaphorically, as in ‘I see what you mean’. But in both cases the metaphorical sense is different to the physical sense.

A related point - the eye of another person might be an object of perception such as when it is being examined by an optometrist. And I can view my own eyes in a mirror. But I cannot see the act of seeing (or for that matter grasp the act of grasping) as that act requires a seen object and the perceiving subject (or grasping and grasped). It is in that sense that eyes and hands may only see and grasp, respectively, what is other to them. That is the salient point.

So the first use of the term ‘object’ employs a different sense of the term ‘object’ than the sense it is used when we say ‘the eye can’t see itself’.

The subject/object duo cannot be broken apart. Each always implies the other. That's the bi-conditional, isn't it? — ucarr

I agree that subjects and objects are ‘co-arising’. This is a fundamental principle in Buddhist philosophy. Schopenhauer uses it to great effect in his arguments. But it doesn’t address the basic issue, that of whether or in what sense mind or consciousness can be known objectively.

Consider the primitive elements of physics. They can be specified in wholly objective terms of velocity, mass, spin, number and so on. Within the ambit of natural science, then objective judgement is paramount. And with respect to at least classical physics, judgements could always be verified against objective measurement. Nowadays the scope of objective judgement covers an enormous range of subjects. But not the nature of first-person experience, and that is intentional, as the subjective elements of experience were assigned to the 'secondary qualities' of objects in the early days of modern science.

The modern mind-body problem arose out of the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century, as a direct result of the concept of objective physical reality that drove that revolution. Galileo and Descartes made the crucial conceptual division by proposing that physical science should provide a mathematically precise quantitative description of an external reality extended in space and time, a description limited to spatiotemporal primary qualities such as shape, size, and motion, and to laws governing the relations among them. Subjective appearances, on the other hand -- how this physical world appears to human perception -- were assigned to the mind, and the secondary qualities like color, sound, and smell were to be analyzed relationally, in terms of the power of physical things, acting on the senses, to produce those appearances in the minds of observers. It was essential to leave out or subtract subjective appearances and the human mind -- as well as human intentions and purposes -- from the physical world in order to permit this powerful but austere spatiotemporal conception of objective physical reality to develop. — Thomas Nagel, Mind and Cosmos

That is the background, if you like, that the 'hard problem' is set against. If you don't see that, you're not seeing the problem. -

The 'hard problem of consciousness'Generally :up: but watch out for the tendency to reify, 'make into a thing'. I think that categorises every attempt to conceive of the probability space as something objective. But the alternative is note purely subjective - note the qualification that due to mathematical regularities for example the Born rule, different observations tend to cluster around specific points. Maybe you could say what is transcendent also transcends the subject-object divide. We all share the same possibilities to some extent. Anyway, enough of that, quantum is always a thread de-railer.

-

Logical proof that the hard problem of consciousness is impossible to “solve”I see no obvious reason why consciousness cannot perceive itself as an object. — ucarr

Grab your right hand with your right hand and report back. -

“Distinctively Logical Explanations”: Can thought explain being?Why is math so faithful? It may be that we can't know that. — frank

Neoplatonic mathematics is governed by a fundamental distinction which is indeed inherent in Greek science in general, but is here most strongly formulated. According to this distinction, one branch of mathematics participates in the contemplation of that which is in no way subject to change, or to becoming and passing away. This branch contemplates that which is always such as it is and which alone is capable of being known: for that which is known in the act of knowing, being a communicable and teachable possession, must be something that is once and for all fixed. — Jacob Klein, Greek Mathematical Thought and the Origin of Algebra.

It's the inherent mysticism of Platonic realism that analytic philosophy finds distasteful.

(Empiricists) view Platonism with skepticism. Scientists tend to be empiricists; they imagine the universe to be made up of things we can touch and taste and so on; things we can learn about through observation and experiment. The idea of something existing “outside of space and time” makes empiricists nervous: It sounds embarrassingly like the way religious believers talk about God, and God was banished from respectable scientific discourse a long time ago.

Platonism, as mathematician Brian Davies has put it, “has more in common with mystical religions than it does with modern science.” The fear is that if mathematicians give Plato an inch, he’ll take a mile. If the truth of mathematical statements can be confirmed just by thinking about them, then why not ethical problems, or even religious questions? Why bother with empiricism at all? — What is Math? -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)Chilling essay by Franklin Foer in The Atlantic: What Musk Really Wants. (It's paywalled but available via e.g. Apple News)

In Elon Musk’s vision of human history, Donald Trump is the singularity. If Musk can propel Trump back to the White House, it will mark the moment that his own superintelligence merges with the most powerful apparatus on the planet, the American government—not to mention the business opportunity of the century.

Many other titans of Silicon Valley have tethered themselves to Trump. But Musk is the one poised to live out the ultimate techno-authoritarian fantasy. With his influence, he stands to capture the state, not just to enrich himself. His entanglement with Trump will be an Ayn Rand novel sprung to life, because Trump has explicitly invited Musk into the government to play the role of the master engineer, who redesigns the American state—and therefore American life—in his own image.

Musk’s pursuit of this dream clearly transcends billionaire hobbyism. Consider the personal attention and financial resources that he is pouring into the former president’s campaign. According to The New York Times, Musk has relocated to Pennsylvania to oversee Trump’s ground game there. That is, he’s running the infrastructure that will bring voters to the polls. In service of this cause, he’s imported top talent from his companies, and he reportedly plans on spending $500 million on it. That doesn’t begin to account for the value of Musk’s celebrity shilling, and the way he has turned X into an informal organ of the campaign.

Musk began as a Trump skeptic—a supporter of Ron DeSantis, in fact. Only gradually did he become an avowed, rhapsodic MAGA believer. His attitude toward Trump seems to parallel his view of artificial intelligence. On the one hand, AI might culminate in the destruction of humanity. On the other hand, it’s inevitable, and if harnessed by a brilliant engineer, it has glorious, maybe even salvific potential.

Musk’s public affection for Trump begins, almost certainly, with his savvy understanding of economic interests—namely, his own. Like so many other billionaire exponents of libertarianism, he has turned the government into a spectacular profit center. His company SpaceX relies on contracts with three-letter agencies and the Pentagon. It has subsumed some of NASA’s core functions. Tesla thrives on government tax credits for electric vehicles and subsidies for its network of charging stations. By Politico’s tabulation, both companies have won $15 billion in federal contracts. But that’s just his business plan in beta form. According to The Wall Street Journal, SpaceX is designing a slew of new products with “national security customers in mind.” ...

It’s not hard to imagine how the mogul will exploit this alliance. Trump has already announced that he will place him in charge of a government-efficiency commission. Or, in the Trumpian vernacular, Musk will be the “secretary of cost-cutting.” SpaceX is the implied template: Musk will advocate for privatizing the government, outsourcing the affairs of state to nimble entrepreneurs and adroit technologists. That means there will be even more opportunities for his companies to score gargantuan contracts. So when Trump brags that Musk will send a rocket to Mars during his administration, he’s not imagining a reprise of the Apollo program. He’s envisioning cutting SpaceX one of the largest checks that the U.S. government has ever written. He’s talking about making the richest man in the world even richer.

I've been wondering what Musk is up to, and this analysis makes perfect sense. Considering what an utter tool Musk is, despite his unarguable engineering and business genius, it is something to be very, very scared of. -

The Biggest Problem for Indirect RealistsIf you agree with me that the forms of reality are really attributed by our cognition; then they are not ‘real’ (in the realist’s sense) but rather transcendentally ideal; and this would be a position which is neither nominalist nor realist (in the sense of those terms as you defined them). — Bob Ross

Very perceptive question. That was the reason I called out scholastic realism, and C S Peirce's recapitulation of it:

For Peirce, universals are real because they represent tendencies or patterns in nature that guide how things behave. His realism is grounded in his belief that the regularities of the world, such as the laws of logic or nature, are not arbitrary constructs of the human mind but are real features of the universe.

and that:

while something real may be said to exist, reality encompasses a broader domain of truths, including abstract concepts like laws of nature or mathematical objects, which don’t exist in a material sense but are still real because they hold independently of personal opinion.

I think that's a clear and intelligible statement of Peirce's distinction between existence and reality. His point is that universals such as logical laws are constitutive of nature itself but not on the same level as phenomena. Bertrand Russell also recognises this:

The relation 'north of' does not seem to exist in the same sense in which Edinburgh and London exist. If we ask 'Where and when does this relation exist?' the answer must be 'Nowhere and nowhen'. There is no place or time where we can find the relation 'north of'. It does not exist in Edinburgh any more than in London, for it relates the two and is neutral as between them. Nor can we say that it exists at any particular time. Now everything that can be apprehended by the senses or by introspection exists at some particular time. Hence the relation 'north of' is radically different from such things. It is neither in space nor in time, neither material nor mental; yet it is something. — Russell, the World of Universals

Russell is intuiting here the distinct ontological status of universals, which he calls out:

We shall find it convenient only to speak of things existing when they are in time, that is to say, when we can point to some time at which they exist (not excluding the possibility of their existing at all times). Thus thoughts and feelings, minds and physical objects exist. But universals do not exist in this sense; we shall say that they subsist or have being, where 'being' is opposed to 'existence' as being timeless.

Compare withConsider the Aristotelian conception of 'nous' (nowadays translated as intellect). It is 'the basic understanding or awareness that grounds rationality. For Aristotle, this was distinct from sensory perception, including imagination and memory, which other animals possess. Discussion of nous is connected to discussion of how the human mind sets definitions (i.e. grasps meaning) in a consistent and communicable way, and whether people must be born with some innate faculty to understand the same universal categories in the same ways' (wiki). (Peirce, of course, came before Russell and Moore's repudiation of idealism, so it was still the dominant influence in the philosophy of his day; Peirce is often categorised as an 'objective idealist' which is nearest to my own inclinations, far as I can tell.)

At the heart of that sense of knowing is something again that we can't easily see, but it's the absence of that sense of division from the world. And that sense of 'otherness' is an existential plight, a way-of-being in the world. But for the pre-moderns, the world was the expression of a will, and was related to on an 'I-thou' basis, rather than the 'us-it' basis which seems natural to moderns. The cosmos was, as it were, animated by the Logos, and this world but one station on the scala naturae, the 'stairway to heaven'. (This doesn't mean for one moment that it was all peace and light in the pre-modern world, history bears witness to that, but stay with me.) We were participants in a cosmic drama, not bystanders in an indifferent world. Before Descartes, 'ideas' were not understood as the possessions of individual minds but as ideas in the Divine Intellect (a foundational principle of Christian Platonism).

In that pre-modern context the knower has a different kind of relationship with the known. We are in some sense united with the known through the ability to grasp its essence, to know what it is. Indeed, metaphysical insight could be construed as 'knowing is-ness', seeing the essence of things.* (You can see how that even underlies early modern science, with the caveat that it is predicated on just this division of subject and object which is the source of the above-mentioned Cartesian anxiety.)

Now to your question as to whether these are 'transcendentally ideal'. I agree, but this can't be taken to mean that they're subjective. Perhaps you could say that they are characteristic of how any mind must work, not simply my mind or yours. That is closer to Peirce's sense.

In all this, I'm trying to maintain the awareness of levels of being, an heirarchical ontology. Of course we can't 'go back' to the pre-modern ontology, but we need to understand and re-interpret it.

-----

* Compare:

I think this vision of 'what is', is at the heart of both philosophy and mysticism, and that we generally don't see 'what is' (tathata in Buddhist philosophy) because of that sense of otherness.If you see "what is" then you see the universe, and denying "what is" is the origin of conflict. The beauty of the universe is in the "what is"; and to live with "what is" without effort is virtue. — J. Krishnamurti

See also Sensible Form and Intelligible Form. -

There is only one mathematical objectQuestion from the stands: are individual numbers considered objects? I mean, '7' sure looks like 'an object of thought'. 'How many did you have in mind?' 'Oh, I was thinking 7'. 'Seven? You're sure about that? Mightn't it be six or eight?' 'No, I think it's definitely seven'.

-

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here):100:

The most damning thing from the trove of evidence — NOS4A2

Not 'the most damning thing'. It is the most trivial and non-incriminating thing. The only kind of thing you will allow yourself to see.

Meanwhile 'On Thursday Trump turned more than a few heads by effectively blaming Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky for Russia’s invasion. Trump said Zelensky “should never have let that war start.”' More here. -

The 'hard problem of consciousness'I suspect that Rouse’s distinction will eventually prove to be untenable. — Joshs

You wish! Just one more knotty philosophical problem that we won't have to deal with. Still, thanks for the acknowledment, appreciate it.

They're fundamentally different under the assumption that consciousness is non-material, which implies dualism, i.e. that we split the world in two, which is implausible. — jkop

Please sir, beg to differ. Dualism posits two substances of different kinds, i.e. mental and material. But consciousness doesn't have to be conceived of as an 'immaterial thing' apart from but different to the physical. Rather it pertains to a different order, namely, the subjective or first-person order, in which it never appears as an object. Rather it is that to which (or whom) all experience occurs, the condition for the appearance of all knowledge. This is basis of phenomenology, which doesn't posit a dualism but nevertheless recognises 'the primacy of consciousness'. The following from Routledge Handbook of Phenomenology on Husserl:

In contrast to the outlook of naturalism, Husserl believed all knowledge, all science, all rationality depended on conscious acts, acts which cannot be properly understood from within the natural outlook at all. Consciousness should not be viewed naturalistically as part of the world at all, since consciousness is precisely the reason why there was a world there for us in the first place. For Husserl it is not that consciousness creates the world in any ontological sense—this would be a subjective idealism, itself a consequence of a certain naturalising tendency whereby consciousness is cause and the world its effect—but rather that the world is opened up, made meaningful, or disclosed through consciousness. The world is inconceivable apart from consciousness. Treating consciousness as part of the world, reifying consciousness, is precisely to ignore consciousness’s foundational, disclosive role. For this reason, all natural science is naive about its point of departure, for Husserl. Since consciousness is presupposed in all science and knowledge, then the proper approach to the study of consciousness itself must be a transcendental one—one which, in Kantian terms, focuses on the conditions for the possibility of knowledge. — p144 -

The 'hard problem of consciousness'I doubt that Penrose thought in terms of the Platonic principle of Cosmic Reason as the essence of Consciousness. — Gnomon

Penrose is quite sympathetic to Platonism, although, due to his commitment to objectivism, his notion of reality is rather one-dimensional.

"The wavefunction is the ontological state of existence of systems in the universe. — Gnomon

I take issue with that in this essay. -

Currently ReadingIs it (Bentley Hart's latest) any good? I have liked some of DBH's books, others I found a bit plodding. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Well, to be honest, I'm finding that he's rehearsing many arguments that I've been having here, so at the moment, early stages, it's a bit ho-hum. I really do like DBH but then I also get the sense he's mainly preaching to the choir a lot of the time. But, I'll persist.

I started Taylor's "A Secular Age," but it's quite long so I'll see how long it takes me. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I've also got that massive doorstop of a book. I've never read all of it. I think it's useful to dive in for some themes that he explores - like his idea of 'the buffered self'. -

“Distinctively Logical Explanations”: Can thought explain being?A different world, if there could be such, would reveal different regularities, but the role of math would be unchanged. — J

I think the interesting question is, then, whether 'our' mathematics would be 'true in all possible worlds'. Meaning, perhaps, that it's not really 'ours'! -

The Biggest Problem for Indirect RealistsOK, sure, I'll come back to your response to my posts about scholastic realism. You said:

For me, ‘reality’ is the ‘totality of what exists’; and ‘existence’ is the primitive concept of ‘being’. ...given the modern perspective, we understand that reality in-itself lacks any forms. Perhaps you can give some insight into this. — Bob Ross

To me, to take a ‘realist’ account, in the medieval sense, is to necessarily posit that the a priori ways by which we experience is a 1:1 mirror of the forms of the universe itself; and I have absolutely no clue why I should believe that. — Bob Ross

From a high level, your instinctive intuition of the world is that you are separate from it. Ideas, including universals, are in the mind but are not attributes of reality as such, which 'lack any forms'. I presume you would also say that you believe the world to exist independently of yours' or anyone's mind, that it is something we discover and explore through empirical means. The customary modern notion of the world is that its 'mind-independent' nature is a hallmark of the kind of reality it has - 'reality is what continues to exist when you stop believing in it' as Philip K. Dick said.

But, and again from a high level, what I'm calling attention to the sense in which the mind constructs reality on an active basis moment by moment. The world is not simply a given, and we ourselves are not passive recipients of information about it. Every sensory signal we receive is absorbed through the process of apperception and then incorporated into the background of our existing understanding. That is the thrust of Kant's 'Copernican revolution in philosophy': contrary to what the empiricists say, the mind is not tabula rasa, a blank slate on which things are merely impressed. Things conform to thoughts, rather than vice versa. (That's why I included the video 'Is Reality Real?' Cognitive scientists are also very much aware of the constructive activities of mind. That's why Kant has been called 'the godfather of modern cognitive science'.)

The second point I want to make is about 'the Cartesian division' (or 'anxiety'). This refers to the notion that, since René Descartes posited his influential form of body-mind dualism, Western civilization has suffered from a longing for ontological certainty, or feeling that scientific methods, and especially the study of the world as a thing separate from ourselves, should be able to lead us to a firm and unchanging knowledge of ourselves and the world around us. The term is named after Descartes because of his divisions of "mind" as different from "body", "self" as different from "other". (Richard J. Bernstein Beyond Objectivism and Relativism, 1983)

That is very much bound up with the ground of modern culture, although as we're embedded in it, it can be very hard to notice (i.e. 'fish unaware of water'.) But the upshot is, just as you say - ideas and forms are in the mind, the vast Universe inchoate, driven only by the processes described by physics, devoid of intentionality. That is the political and philosophical background of modern liberal individualism.

I have more to add on why I hark back to scholastic realism, but that's enough for one post. -

The Empty Suitcase: Physicalism vs Methodological NaturalismI agree, good book. Standard text in philosophy of science in years past.

-

“Distinctively Logical Explanations”: Can thought explain being?From the abstract of the paper:

There is a major debate as to whether there are non-causal mathematical explanations of physical facts that show how the facts under question arise from a degree of mathematical necessity considered stronger than that of contingent causal laws

This is very much a question about the ontological status of mathematical laws—whether they are conceptual tools imposed by observers to describe the world, or whether they reveal some deeper, inherent structure of the universe, suggesting an a priori necessity. I think that the idea that the world might exhibit a kind of mathematical necessity independent of human observation is resisted because it seems to suggest that something beyond the physical and observable, namely abstract mathematical truths, might be causally efficacious. Empiricism doesn't like that.

“The facts allegedly explained by a DME do not obtain because of a mathematical necessity but by appeal to the world’s network of causal relations. . . . [Mathematics] is not a constraint on what the physical world must be.” — J

Isn't mathematical physics a distillation of quantifiable values mapped against observable data? Insofar as mathematics is used to quantify and then model some object of analysis, then mathematical logic is applicable to those models. The mathematical structures qua predictive principles accurately capture and model the relevant attributes of the objects in question, such that they will conform with those predictions. It doesn't mean that the outcome is constrained by the model, but that the model accurately reflects the real attributes of the objects and relationships in question. So mathematics models the world because the world exhibits regularities that can be mathematically described, not because the world is constrained by the mathematical framework. But because those relationships are faithfully captured by the mathematics then mathematical logic can be applied to it's analysis, and further, often unexpected, entailments can be discovered (as discussed in Eugene Wigner's famous paper The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Maths in the Natural Sciences.) -

The 'hard problem of consciousness'Ever read The Emperor's New Mind by Roger Penrose? — J

Tried and failed. The maths was beyond me. I’ve often enjoyed Sir Roger’s talks on other topics. I’ve recently written a Medium essay about his views on QM. -

The 'hard problem of consciousness'Sense-making is about pragmatically relevant actions , not concordance with ‘reality as it is’, whatever that’s supposed to mean. This doesn’t make what sense-making reveals as an illusion, or mere appearance as opposed to the really real. It shows us that this is what ‘reality as it is’ IS in itself. — Joshs

I’ve learned that the principle is called ‘relevance realization’ or ‘the salience landscape.’ It’s a guiding principle for all organic life. But self-aware rational beings might have requirements beyond those of other life-forms - think Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Other organisms are not able to consider the nature of existence in the way h.sapiens is, so questions of truth or falsehood don’t arise as part of their ‘salience landscape’.

As for the ‘in itself’ that has been construed in diverse ways throughout history. In philosophy the problem arises from the intuition that the way humans construe the nature of existence might be obscured by some deep-seated cognitive error. That was the fundamental insight behind the origin of the Western metaphysical tradition with Parmenides. But philosophy in that sense seems impossible in the age in which we live, burdened as we are by the enormous accumulation of facts and theories that no single individual can hope to comprehend. -

The Biggest Problem for Indirect RealistsTo me, to take a ‘realist’ account, in the medieval sense, is to necessarily posit that the a priori ways by which we experience is a 1:1 mirror of the forms of the universe itself; — Bob Ross

By way of footnote, there is a sense in which that is true for Aristotelian and Thomist philosophy. It is because the forms or essences of particulars are what is most real about them, and nous is able to directly apprehend them, whereas the senses only know indirectly. Anyway thanks for your patience Bob. It's a thesis I'm pursuing in history of ideas but very I'm very much a voice in wilderness. -

Logical proof that the hard problem of consciousness is impossible to “solve”That would mean consciousness is matter/energy at its core. — Patterner

Or vice versa. -

The 'hard problem of consciousness'm. I think Hoffman learns the wrong lessons from evolutionary theory. — Joshs

Possibly. I’m pretty confused about aspects of his theories. The reason I mentioned him was as a foil to the last paragraph of the OP that appeals to evolutionary biology in support of scientific realism. I was pointing out that Hoffman’s evolutionary cognitive theory doesn’t support realism. -

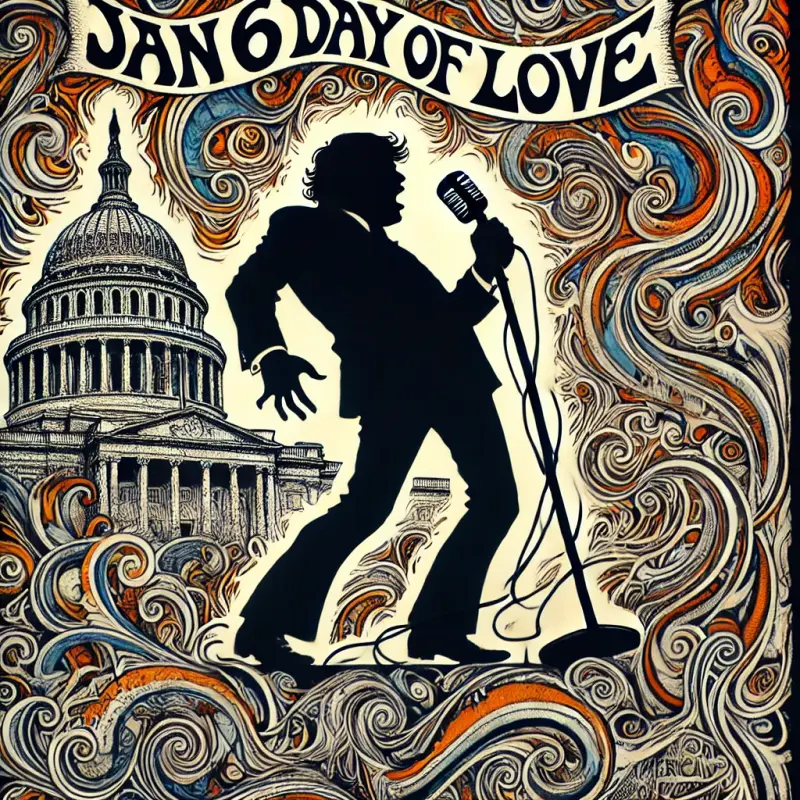

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)One thing for sure, the Master Propogandist has sure as hell put Jan 6 front and centre for the last three weeks of the run up, with his Day of Love shtick. I'm going to get AI to make me a 1969 style psychedelic poster with Day of Love in flouro, and DJT against the MAGA mob in silhouette.

-

Logical proof that the hard problem of consciousness is impossible to “solve”I don't agree with it. I just don't have a problem with it — Philosophim

You're taking issue with it, saying he's mistaken, so don't be too polite about it. :wink:

I disagree with his solution to the problem, because he also currently has no evidence to deny that subjective consciousness could be an aspect of matter and energy. — Philosophim

A lot is resting on 'aspect' there. You could mean panpsychism, or dual aspect monism or some other view. Certainly as physical beings we are constantly energetic. If you read more of Chalmers, you will see he in no way discounts the neurological perspective. But he says it must be combined with a phenomenological approach because that methodology specficially integrates a first person perspective.

Speaking of evidence - and here we're talking philosophically not scientifically - matter is only known to us contingently and indirectly. We don't know what it actually is. We receive visual and auditory data about it, on that we all agree, and then interpret it. When you say that 'neurons cause consciousness', that they are an aspect of consciousness, that is not in doubt. What that leaves out is the mind that makes the judgement. As it must, because mind is not objective. But then as Schopenhauer says, 'Materialism is the attempt to explain what is immediately given us by what is given us indirectly'.

Space is a concept we use in relation to matter. We measure it with matter, yet space itself is not matter, but the absence of it. Time is not an existent 'material' concept, but it is is determined by watching and recording the differences in materials. Subjective consciousness as well, if it can only be known by being a material, is still known and defined in terms of the material that it is. — Philosophim

What do you make of this, then? it does have bearing as I will explain.

The problem of including the observer in our description of physical reality arises most insistently when it comes to the subject of quantum cosmology - the application of quantum mechanics to the universe as a whole - because, by definition, 'the universe' must include any observers.

Andrei Linde has given a deep reason for why observers enter into quantum cosmology in a fundamental way. It has to do with the nature of time. The passage of time is not absolute; it always involves a change of one physical system relative to another, for example, how many times the hands of the clock go around relative to the rotation of the Earth. When it comes to the Universe as a whole, time looses its meaning, for there is nothing else relative to which the universe may be said to change. This 'vanishing' of time for the entire universe becomes very explicit in quantum cosmology, where the time variable simply drops out of the quantum description. It may readily be restored by considering the Universe to be separated into two subsystems: an observer with a clock, and the rest of the Universe.

So the observer plays an absolutely crucial role in this respect. Linde expresses it graphically: 'thus we see that without introducing an observer, we have a dead universe, which does not evolve in time', and, 'we are together, the Universe and us. The moment you say the Universe exists without any observers, I cannot make any sense out of that. I cannot imagine a consistent theory of everything that ignores consciousness...in the absence of observers, our universe is dead'. — Paul Davies, The Goldilocks Enigma: Why is the Universe Just Right for Life, p 271

The point being, physicalism only gets to a certain point before having to admit the reality of 'the observer', who is not in the picture. Happens at the other end of the scale, too. It is another aspect of the 'hard problem'.

It is great that you like the idea of subjective consciousness as another category of thinking — Philosophim

I don't think that its another category of thinking. It's the first- and third-person perspectives. -

Logical proof that the hard problem of consciousness is impossible to “solve”The idea is that, in addition to the physical properties of matter we're familiar with - mass, charge, spin, etc. - properties that we can measure and study with our physical sciences, there is a mental property. Not being physical, we cannot measure and study it with our physical sciences. It is no more removable from matter than mass is. Even though it is not physical, it is not "apart from the physical reality we live in." — Patterner

I'd sign off on that as in interpretation of Chalmers.

Another, from Bernardo Kastrup:

Chalmers basically says that there is nothing about physical parameters – the mass, charge, momentum, position, frequency or amplitude of the particles and fields in our brain – from which we can deduce the qualities of subjective experience. They will never tell us what it feels like to have a bellyache, or to fall in love, or to taste a strawberry. The domain of subjective experience and the world described to us by science are fundamentally distinct, because the one is quantitative and the other is qualitative. It was when I read this that I realised that materialism is not only limited – it is incoherent. The ‘hard problem’ of consciousness is not the problem; it is the premise of materialism that is the problem.

Then, as somebody with a strong analytic disposition, I immediately felt a gaping abyss in my understanding of the world. So I started looking for an alternative, correcting those previously unexamined assumptions – materialist assumptions – that I was making, replacing them with what I thought was a more reliable starting point and trying to rebuild my understanding of the world from there. I ended up as a metaphysical idealist – somebody who thinks that the whole of reality is mental in essence. It is not in your mind alone, not in my mind alone, but in an extended transpersonal form of mind which appears to us in the form that we call matter. Matter is a representation or appearance of what is, in and of itself, mental processes. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)I generally resist posting partisan media here but this one I couldn't pass up.

Responding to a question from an undecided voter, Trump called January 6th a 'day of love'. -

The 'hard problem of consciousness'Materiality is discursive in the sense that it consists of reciprocal acts of affecting and being affected that form normative systems. — Joshs

But to me that requires the existence of the kind of agency that only begins to appear with organic life (by no means only conscious agency.) That is the reason I'm open to biosemiosis but not to pansemiosis. The first refers to the process of semiosis (the production and interpretation of signs) specifically within biological systems. It focuses on how living organisms generate, interpret, and respond to signs and signals in their environment—such as how cells communicate or how animals process sensory information - Pattee's area of expertise. The second extends the idea of semiosis beyond biological systems, suggesting that semiosis is a universal feature of reality, occurring at all levels of existence, including inanimate matter. In this view, the entire cosmos can be understood as engaging in some form of sign interpretation or meaning-making, not just living organisms. That doesn't register for me.

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum