-

On the matter of logic and the worldlifespan..............just wondering. — Mww

The dates were intended to reinforce the idea that Kant was not able to benefit from Darwin's later work on the theory of evolution, in that today we can explain Kant's "a priori" knowledge as innate knowledge, a product of billions of years of evolution. -

On the matter of logic and the worldSo, if indeed it is the case that our perceptions and conceptions are solely the product of evolution, then why should there be any basis for trust in the independent capacity of reason to arrive at truth? — Wayfarer

At the very least we need to be able to reason in order to survive. As Hoffman argued, reason allows us to navigate the world around us and has evolved to what it is today through natural selection.

I believe that in order to survive, I should not walk off a cliff. I can justify this by noticing that others who have done this have not survived. It is true that if I walk off a cliff I will not survive. Therefore, I have knowledge that in order to survive I should not walk off a cliff, where knowledge is justified true belief. My reasoning has led me to a truth.

Reasoning to survive exists outside language, in that the Neanderthals were able to successfully survive for almost 400,000 years without language. The Neanderthal reasoned and knew without language the truth of the danger of walking off a cliff.

IE, visceral reasoning arrives at truths.

Isn't confidence in reason justifiable because it is not solely dependent on biological evolution? — Wayfarer

We know that reason may lead to truths in knowing how to survive, but where is the truth beyond that which is necessary to survive. Where is the truth in a Derain. Where is the truth in an aesthetic experience.

I agree that once the ability to reason has evolved through the biological necessity of survival, then we can use our ability to reason about other things not to do with survival, such as trying to understand why a Derain is aesthetically more successful than a Hockney.

Although reason was born out of the necessity to survive, reason can now stand on its own two feet and go out into the world and reason about a whole range of different things.

It is true that when I look at a Derain I experience an aesthetic form. But what exactly is true. It cannot be the form that is true. It cannot be my response that is true. It cannot be the interaction between the form and my mind that is true. It is the proposition "when I look at a Derain I experience an aesthetic form" that is true. Truth also exists in language.

IE, linguistic reasoning also arrives at truths

In other words, to rationalise what we take to be true in terms of what is advantageous to survival, sells reason short - a very common tendency in modern philosophy. — Wayfarer

There are two types of truth - a visceral truth known outside of language and a linguistic truth known within language. There are also two types of reasoning - a visceral reasoning outside of language and a linguistic reasoning within language.

IE, as of necessity Philosophy uses language, Philosophy is also concerned with using reason as a means of discovering truth within language. -

On the matter of logic and the worldYour accounting, or sourced from secondary literature? — Mww

I had been reading The Critique of the Power of Judgement because of my interest in aesthetics. The title stuck in my mind and I mistakenly wrote in my post Critique of the Power of Judgement rather than Critique of Reason.

Many people are far more knowledgeable about Kant than me, so I think it only wise to also refer to secondary sources, such as the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Don't you agree ? -

On the matter of logic and the worldIf language is self referential, the there are two ways to think about this. ..................................One way says the world as the world is bound up with the ways we know it; ontology and epistemology cannot be separated and my coffee cup IS a coffee cup AS a bundled phenomenon. The idea of the cup is literally the cup-thing itself. So, I point to my cat, and the pointing, the concept, the predelineation of the past informing the present occasion as well as the anticipation of what the "future cat" will be, do, all of this is constitutive of the occurrent apperception of my cat. All of a piece. Any separation of parts would be an abstraction, which is fine because this is what analysis is, as long as we don't think analytically determined entities ae entities in their own right............................................. Another way is to understand that the knowledge that brings the palpable thing into understanding and familiarity is qualitatively distinct from the palpable thing. To me, this is a very strong and even profound claim. It is not about some noumena that is postulated but beyond sight and sound; it's about the palpable presence of the thing, and its being alien to the understanding, so their you are, confronting metaphysics directly. This is called mysticism. — Constance

I agree that there there are two distinct ways in which we understand the external world, and these may be described in various ways.

1) Metaphysics, our past history, Sartrian existence and Kantian a priori knowledge are all aspects of the same thing. This is, as you say, about "confronting metaphysics directly".

2) Physics, our present situation, Sartrian essence and Kantian a posteriori knowledge are also all aspects of the same thing. This is, as you say, "apperception".

Each is distinct, as hardware is distinct from software, yet both are mutually dependent, and both are required for the proper functioning of the whole human organism.

The colour red is experienced both physically and metaphysically

Consider our experience of the colour red. From physics, I know that the wavelength of red light is 700nm. But I also have a private subjective experience of the colour red, an experience that can never be described to another person. At the moment of having the subjective experience of the colour red, it is not the case that I am observing the colour red, rather, it is the case that I am the experience of the colour red. An experience transcending any physical knowledge into an immediate and visceral metaphysical knowledge.

IE, our knowledge of, for example, the colour red, is both physical and metaphysical

Evolution explains Kant's a priori

We are observers of the external world, yet we are also part of the world. We have an existence upon which we build an essence. This existence did not arise yesterday, or the day we were born, but has been underway for billions of years. We have evolved in synergy with the world. Humans are born with certain innate abilities, in that the brain is not a blank slate, as described by both post-Darwinian "evolutionary aesthetics" and "evolutionary ethics". In the 3.7 billion years of life on earth, complex life forms have evolved to have certain innate intuitions necessary for continued survival. It is not the case that we have certain intuitions and they happen to correspond with the world, rather, our intuitions were created by the world and therefore of necessity correspond with the world. Through the process of evolution the mind gradually models the world around it. If the model had not been correct, then the mind and body would not have survived. Therefore, the sensible intuitions innate within the mind have been created by the world in which the brain has survived.

IE, it is not the case that the mind has an intuition of the world that it exists within, rather, the intuitions of the mind necessarily correspond with the world it exists within, otherwise it would not have been able to successfully survive and evolve.

We understand the world both in a Kantian a priori and a posteriori way

The two distinct ways we relate to the world can be further understood within Kant's theory of the "synthetic a priori". Kant combined the ideas of the Empiricists and the Rationalists. For the Empiricists, such as Hume, only what can be observed has meaning, where a posteriori knowledge is "as mere representations and not as things in themselves"

For the Rationalists, such as Leibniz, understanding is in the mind, where a priori knowledge is "only sensible forms of our intuition, but not determinations given for themselves or conditions of objects as things in themselves".

Empiricism claims that our ideas are fashioned out of experience between an observer and an external world and the ideas thus formed if they have any bearing on external reality then elementary sensations are bound together by some principle of association. Kant argued that on this reading, science could not have developed, yet, as science is successful, the principles of association must have been provided by the observer such that "nothing in a priori knowledge can be ascribed to objects save what the thinking subject derives from itself".

The observer can only understand what they observe if they have a prior ability to experience what they observe, in that we are able to see the colour red but not the infra-red because of our innate abilities. Kant wrote in his Critique of the Power of Judgement : "We can only cognize objects that we can, in principle, intuit. Consequently, we can only cognize objects in space and time, appearances. We cannot cognize things in themselves". (A239). Foundational to all our understanding of what we observe is our innate understanding of space and time: "Space and time are merely the forms of our sensible intuition of objects. They are not beings that exist independently of our intuition (things in themselves), nor are they properties of, nor relations among, such beings". (A26, A33)

It is true that Kant (1724 to 1804) did not propose an evolutionary mechanism for a priori pure intuitions, as he was not able to benefit from Darwin's (1809 to 1882) theory of evolution, Kant's principle of "synthetic a priori judgements" remains valid.

IE, We are born with certain innate abilities that have taken billions of years to evolve, and based on these innate abilities we can observe the external world, but we can only observe in the world what our innate abilities allow us to observe. Our understanding of the world is from observed phenomenon which are given meaning by a pre-existing and innate understanding of them. The physics of the world is understood through an innate knowledge that transcends experience, ie, a metaphysics.

Our understanding of the world must always be limited

FH Bradley's regression argument illustrates the that relations have no ontological existence in the external world. The Binding Problem, that we experience a subjective whole rather than a set of disparate parts, illustrates that relations do have an ontological existence in the mind. As Kant argued that we make sense of the world by imposing our a priori knowledge onto our a posteriori observations in the external world, similarly we can also make sense of the world by imposing a reasoned relational logic onto a relation-free external world.

IE, both these show the inherent limits to our understanding of the world, in that we will only ever be able to understand those aspects of the world for which we have an a priori ability to understand. This means that there are things about the world that will forever be beyond our imagination, as a horse's understanding of the allegories in The Old Man and the Sea will forever be beyond the horse's imagination.

Language is more than self-referential

As language is, taking one example, the observed a posteriori linkage between a name "red" and a known a priori part (red), rather than being said to be self-referential in the sense of the Coherence Theory of Language, language is still able to refer to the world in the sense of the Correspondence Theory of Language.

Summary

We know the world in two distinct ways - i) metaphysically, rationally, as an evolutionary memory, as a Sartrian existence, a Kantian a priori ii) physically, empirically, as a present experience, as a Sartrian essence and a Kantian a posteriori. -

On the matter of logic and the worldOhfercrisakes.....that he wanted to deny it is every bit as false as he did deny it. He equally never did either. — Mww

True, but that is not what was written.

You are ignoring the qualifier "as much as" which is qualifying the clause that follows it - "Kant wanted to deny metaphysics". -

On the matter of logic and the world"as much as Kant wanted to deny metaphysics"....................This is catastrophically false, but none of your co-respondents noticed nor cared — Mww

Speaking as a co-respondent, the phrase used was not "Kant denied metaphysics", which may well be "catastrophically false". The phrase was "as much as Kant wanted to deny metaphysics", which has a completely different meaning and is not "catastrophically false". -

On the matter of logic and the worldParadoxes like Zeno's should be telling us that geometry and reality are very different..................but the world altogether is not logical; it is alogical, apart from logic, qualitatively different................language is mostly self referential....................We live in epistemology. The world before us apart from this is utterly metaphysical. — Constance

I agree with what you have written.

The question is why are geometry and reality very different

For me, the reason is that relations are foundational to our logic, yet relations have no ontological existence in the external world.

This explains why geometry and reality are very different, the world is alogical, language is self-referential, we live in epistemology and the world is utterly metaphysical.

If there was a more persuasive explanation why logic and reality are very different than because of the the nature of relations, then this would be of interest.

The next question is why we need to know why geometry and reality are very different

Perhaps it is sufficient to know what pragmatically works. I turn the ignition key on my car and the engine starts. I don't need to know why the engine starts, all I need to know is that turning the key starts the car. Why not treat the external world as an empirical experience and not search for any sense beyond this.

My justified belief that relations within logic are fundamentally different to relations within reality can never be knowledge

My belief is that logic and reality are very different because of the nature of their relations, and this I can justify. However, my justified belief that logic and reality are very different because of the nature of their relations can never be knowledge, as I can never have a true understanding of a reality that is relation-free using reasoning where relations are fundamental.

In this respect, my justified belief remains a working hypothesis, and will remain so

until presented with a more persuasive explanation as to the nature of logic and reality. My belief must always remain an invention rather than a discovery, as my belief transcends what I can ever discover.

Summary

The nature of relations is the fundamental barrier between our understanding of the external world and the external world itself. -

Black woman on Supreme CourtThe Democratic President specifically asked for a woman rather than a man, and yet the nominee cannot explain the difference between a woman and a man.

If the nominee does not know whether they are a woman or a man, then perhaps they should recuse themselves from the nomination, as the President specifically asked for a woman. -

On the matter of logic and the worldIf logic qua logic can produce nonsense like this, then as a system of understanding the world, it is more than suspect. It is "wrong". — Constance

Language is more metaphor than logic

I have always been mystified that adding one-half plus one-quarter plus one-eighth plus one-sixteenth etc adds up to one, in that adding together an infinite number of things results in a finite thing.

I can explain this paradox by understanding that relations are foundational to the logic we use, in that 5 plus 8 equals 13, etc, yet relations, as illustrated by FH Bradley, have no ontological existence in the world.

It is therefore hardly surprising then that paradoxes will arrive when comparing two things that are fundamentally different, ie, our logic and the world.

But I do not at present see any way around any of these — Constance

We must be remember that when paradoxes do arrive, that this will be an inevitable consequence of the nature of logic, rather than indicative of anything strange happening in the world.

The fact that logic will inevitably lead to paradox explains why metaphor is such an important part of language, so much so, that a case may be made that "language is metaphor". -

What type of figure of speech is "to see"Here's a paper by Lakoff and Johnson (PDF): Conceptual Metaphor in Everyday Language. It gives an idea of how deeply metaphorical our language (and our thinking) is. — jamalrob

I see where you are coming from.

Language as metaphor

Nietzsche wrote “We believe that when we speak of trees, colours, snows, and flowers, we have knowledge of the things themselves, and yet we possess only metaphors of things which in no way correspond to the original entities.”

Metaphor is language’s most powerful weapon.

Consider "I can see the solution" and "I can see the apple". We commonly assume that "I see" is used metaphorically in the first instance and literally in the second instance, however language is more complex than this.

We talk all the time with metaphors but do not notice this because we use them naturally, both in daily life and in science - Maxwell’s demon, Schrödinger's cat, Einstein’s twins, the Greenhouse Effect, natural selection, dendritic branches. Metaphors are not paraphrases for other literal expressions, but are how ideas are expressed. Metaphors describe the world and are not explanations.

Metaphors and Indirect Realism

The conceptual metaphor, understanding one idea in terms of another, is foundational to the meaning of Indirect Realism.

Indirect Realism is the belief that our conscious experience is not of the real world itself but of an internal representation of the real world

As "the solution" is not an object in the world but a concept in the mind - "the apple" is also not an object in the world but a concept in the mind. Therefore, as we treat "I see the solution" as a metaphor, we should also treat "I see the apple" as a metaphor rather than literally.

A belief in Indirect Realism leads to a belief that not just is metaphor important in language, but "language is metaphor".

However, even the insight that our language is deeply metaphorical will not lead, as Lakoff and Johnson write, to any new perspective about "the truth", as "understanding one kind of experience in terms of another kind of experience" will always lead to an infinite regression, where "the truth" will always remain, as I see it, out of reach. -

Aristotle: Time Never BeginsIf we would consider the omnipresent virtual particle fields residing in the vacuum of nature the eternal unmoved prime mover, we would still be left with the question where that came from. — EugeneW

Aristotle

Aristotle's answer would be that the universe is eternal having never come into existence. His is not the God of Genesis who created the world out of nothing.

But the universe is in eternal motion, and for Aristotle the universe needs a cause for its continuing existence and motion, and that cause is a God, outside the world, changeless and immaterial.

Aristotle's theology is set out in books VII and VIII of Physics and book XII of Metaphysics

Such a God is an "unmoved mover", not responsible not for the creation of the universe, as for Aristotle the universe is eternal, but responsible in a non-physical way for the continuing motion within the universe.

Modern interpretation

Aristotle's belief that the universe is eternal seems reasonable. If a thing exists, as it is almost unimaginable that at a later moment in time it could disappear into absolute nothingness, it is also almost unimaginable then at an earlier moment in time it could have appeared from absolute nothingness.

Gravity may also be considered an "unmoved mover", whether considered as a force or curvature in space-time. A "mover" with infinite range where all things are attracted to one another, and "unmoved" in that whether a force or a curvature in space-time can cause motion without being in motion itself. -

Aristotle: Time Never BeginsBut what brought space and time into being? — EugeneW

Aristotle in Physics Book 8 claims that motion is everlasting, has no beginning and will have no end.

And yet he discusses the "unmoved mover", where "the first movement is moved but not by anything else, it must be moved by itself"

Although his "unmoved mover" has been identified with a spiritual explanation, Aristotle in Physics Book 8 doesn't explain its nature.

Today, this "unmoved mover" can be explained in more scientific terms, without the need to address what brought space and time into existence. -

Aristotle: Time Never BeginsAristotle is arguing first that motion in the universe is everlasting and second that the motion we observe in the world must have its primary cause in something that cannot be in motion, a first immaterial "unmoving mover".

He writes at the end of section 5 of Physics Book 8 - "From what has been said, then, it is evident that that which primarily imparts motion is unmoved: for, whether the series is closed at once by that which is in motion but moved by something else deriving its motion directly from the first unmoved, or whether the motion is derived from what is in motion but moves itself and stops its own motion, on both suppositions we have the result that in all cases of things being in motion that which primarily imparts motion is unmoved."

The question is, are his premises sound and his his argument valid ?

As @Metaphysician Undercover pointed out, the paragraph in the OP has been taken out of context.

Aristotle's inference of a spiritual rather than physical explanation for an "unmoving mover" may be brought down to earth.

1) Imagine a rock travelling through space at 10,000 km/hour. In Aristotle's terms, where is the unmoving mover that keeps the rock travelling forwards at a constant speed ? How to explain the Law of Conservation of Energy, whereby the kinetic energy of the rock is maintained ?

However, motion is relative, and we may consider the rock as stationary within a moving environment. In this case, the rock being stationary, no unmoving mover is needed, and the existence of an unmoving mover is not required.

2) Imagine the same rock in distant space. Movement is not a property of a single body, but is a property that emerges when more than one body are in near location, whether the gravitational force between the moon and the Earth or the magnetic attraction between two magnets. If another body approaches this particular rock, the paths of the bodies will be changed by a gravitational attraction.

In this case, the primary mover is gravity, which may be understood as a curve in space, and in Aristotle's terms, an unmoving mover

In summary, in both cases, it is not necessary to consider a mysterious entity outside the known universe, in that the "mover" can be explained as a physical state of affairs within current time and space. -

Aristotle: Time Never BeginsI know certain things by acquaintance - a headache, an acrid smell, the colour red, a sweet taste, a screeching noise. I know other things by description - Aristotle, Sherlock Holmes, a unicorn.

I cannot know time by acquaintance, as "We can only experience the moment we are in. We cannot experience at this moment either the moment before this moment or the moment after this moment. Therefore, we can never directly experience either the past or the future."

I can only know time by description.

As Aristotle, as well as everyone else, only knows time by description and not acquaintance, his conclusion that time is eternal and without beginning must remain a hypothesis, interesting, but still an unprovable hypothesis. -

Aristotle: Time Never BeginsDo you think Aristotle's argument is sound or valid? — Kuro

The phrase "Aristotle's argument is correct" is incorrect.

A sound argument has a different meaning to a valid argument.

There should be four questions within the poll:

Aristotle's argument is sound

Aristotle's argument is not sound

Aristotle's argument is valid

Aristotle's argument is not valid

Aristotle's argument is valid but not sound.

His premise is false - "Now since time cannot exist and is unthinkable apart from the moment, and the moment a kind of middle-point, uniting as it does in itself both a beginning and an end, a beginning of future time and an end of past time"

His reasoning is correct

His conclusion is false - "it follows that there must always be time"

There is a problem with Aristotle's premise

We can only experience the moment we are in. We cannot experience at this moment either the moment before this moment or the moment after this moment. Therefore, we can never directly experience either the past or the future.

Therefore, as we can never directly experience either the past or the future, we can never have first hand knowledge of the meaning of the terms time, past, present, eternal, creation or motion.

Therefore, Aristotle's conclusion that time and motion are eternal can only ever be an interesting hypothesis. -

Is everything random, or are at least some things logical?I'd like to think that natural selection is not random. — Cidat

If a drop of rain falls downwards, the path of the raindrop is not random, in that the new position of the raindrop depends on its previous position. The path of the raindrop is also logical, in that it is following a set of rules, in this case, the laws of nature. Therefore the path of the raindrop is both logical and not random.

Extrapolating, natural selection is both logical and not random, meaning that the fact that one species dominates is both logical and not random. However, any final situation, regardless of what it had turned out to be, would be both logical and not random. Two species dominating would have been both logical and not random. No species dominating would have been both logical and not random.

It does not follow that because the final situation is both logical and not random, the final situation has been teleologically pre-determined. Even though the final situation is both logical and not random, it does not follow that the final situation has any special meaning.

The fact that a sequence of events is both logical and non random is insufficient to give meaning to any subsequent state of affairs. -

Replies to Steven French’s Eliminativism about Objects and Material Constitution. (Now with TLDR)I regret to inform that the Eiffel Tower does not exist, although on the left bank in Paris there's a bunch of iron atoms shaped in the form of the Eiffel Tower. — Olivier5

Depends what one means by exist.

We seem to agree that the Eiffel Tower does not exist in Platonic Form, in that it seems a strange idea that prior to 1889 the Eiffel Tower existed below the ground in Algeria in the form of iron.

But your previous comment "As long as I can eat and work on it, and occasionally climb on it, the table is real enough for me" suggests that we agree the Eiffel Tower exists in Aristotelian form, in that we can both eat in the Jules Verne Restaurant and visit the Observation Platform. -

Replies to Steven French’s Eliminativism about Objects and Material Constitution. (Now with TLDR)If the world offers no information regarding the independent existence of apples and tables, then I cannot discover whether I just ate an apple or a table — Cuthbert

Because there is no information in the Eiffel Tower that the Andromeda Galaxy exists, it does not follow that we have not been able to discover the existence of either the Eiffel Tower or Andromeda Galaxy. -

Replies to Steven French’s Eliminativism about Objects and Material Constitution. (Now with TLDR)If you can pick up apples for sixty pence a pound in Tesco, then you can pick up a pair of elementary particles for the same low price. — Cuthbert

It's even a better deal than that, in that for the low price of 60 pence, one can get from Tesco's 5 * 10 to the power of 29 elementary particles. Though Asda are slightly cheaper. And Waitrose definitely more expensive. -

Replies to Steven French’s Eliminativism about Objects and Material Constitution. (Now with TLDR)My point was that the mind is no different than everything else in that everything is both the effect of causes and the cause of subsequent effects. — Harry Hindu

Agree, the mind is part of the world, having evolved in synergy with the world, possibly over a period of 800 million years.

None of this explains what "consciousness" or "proto-consciousness" is. — Harry Hindu

Agree, the nature of consciousness is mysterious. Panprotopsychism is just establishing the map, not explaining the territory.

If these relations did not exist ontologically, then what reason would there be for us perceiving them? — Harry Hindu

The original Steve French article is arguing for an Ontic Structural Realism, the view that structure is ontologically fundamental, and where objects at at both the fundamental and "everyday" levels should be eliminated.

FH Bradley used a regress argument against the ontological existence of relations.

Question One

If relations only existed in the external world and not the mind, how are we able to perceive things that don't exist in the external world, such as Sherlock Holmes, ghosts and unicorns ?

Question Two

When looking at an object in the external world, our knowledge of it must necessarily be incomplete. Yet when looking at something in the world that is incomplete, the mind will fill in the blanks and make a complete image. When thinking about an object about which we have limited knowledge we still think of it as a complete whole.

If relations only existed in the external world and not the mind, how to explain the principle of closure ?

Question Three

If relations exist in the external world, then a table, which is a particular set of elementary particles, exists as an object. It follows that every possible set of elementary particles in the external world will also exist as an object. For example, a single elementary particle in the apple and a single elementary particle in the table will exist as an object, the set of elementary particles in the table and a single elementary particle in the apple will also exist as an object, etc. It follows that the number of objects in the external world will be more than the number of elementary particles in the world.

How can there be more things existing in the external world than there are elementary particles ?

Question Four

If the apple exists as an object in the external world, then every pair of elementary particles in the external world would also exist as an object. It logically follows that a single elementary particle in the table in front of me and a single elementary particle 90 billion light years away must also exist as an object.

The question is, does this object exist instantaneously, or is its existence dependent of information passing between the two elementary particles at the speed of light ?

Question Five

If relations only existed in the external world, the apple as one set of elementary particles will be an object, the table as another set of elementary particles will be another object, but also the combined set of elementary particles in the apple and table will be another object again.

Where is the information in the external world that the apple as an object exists independently of the table as an object ?

Question Six

We know that we perceive relationships that don't exist in the external world, such as Sherlock Holmes, ghosts and unicorns. Therefore, relationships don't need to exist in the external world in order for us to be able to perceive relationships, meaning that there are some relationships that exist only in the mind.

When we observe the external world and perceive a particular relationship, such as a table, as we are able to perceive relationships that don't exist in the external world, how do we know that the relationship we are perceiving exists in the mind or in the external world ?

Summary

It seems to me that FH Bradley's regress argument makes more sense than relations having an ontological existence in the external world. -

Replies to Steven French’s Eliminativism about Objects and Material Constitution. (Now with TLDR)Well, maybe, but I see no reason to believe that my table does not exist, nor any reason to attribute any protopsychism to it. — Olivier5

1) I agree that the elementary particles that make up what we call a table exist in the external world, and where each elementary particle is located at a particular time and space. I agree that the table exists as a concept in our minds. The information that this particular set of elementary particles each located at a particular time and space is in the form of a table exists in our mind.

The question is, where in the external world is the information that this particular set of elementary particles each located at a particular time and space is in the form of a table ?

2) The Universe has been around for about 14 billion years. It is estimated that the first neurons appeared on Earth about 600 million years ago.

If consciousness did not come from a pre-existing proto-consciousness, then where did consciousness in the mind come from ? -

Replies to Steven French’s Eliminativism about Objects and Material Constitution. (Now with TLDR)I don't like using terms like "external" and "internal" because it seems to divide the world into two (dualism) unnecessarily. — Harry Hindu

In any discussion of the mind the concept of dualism is unavoidable, as you say yourself: "We all know that the world has an effect on the mind and the mind affects the world", instantly setting up a dualism between the world and the mind.

Steve French is misusing the term eliminativism...........Not neccessarily. — Harry Hindu

I agree that in principle, anyone denying the existence of some type of thing is an eliminativist.

However, in practice, within philosophy, eliminativism always refers to eliminative materialism, which is a theory about the nature of the mind. Even within your own text - Holbach (1770) are eliminativists with regard to free will - Hume (1739) was arguably an eliminativist about the self. The SEP article concludes with the line: "While it is true that eliminative materialism depends upon the development of a radical scientific theory of the mind, radical theorizing about the mind may itself rest upon our taking seriously the possibility that our common sense perspective may be profoundly mistaken"

Then it seems that if the relations in our mind don't represent the world as it is then our understanding of the world is radically wrong. — Harry Hindu

As you later say about observing an apple: "Visually, you only perceive one side of the apple" and "You can perceive the whole apple tactilely, but not visually".

When observing an apple, our mental representation of the apple must always be incomplete, in that we may only be looking at one or two sides, we may not be looking inside the apple, we may not be smelling the apple, etc. As our representation must inevitable always be incomplete, we can never represent the apple as you say "as it is".

The fact that any representation can never be complete does not mean that such representation is radically wrong, all we need is that such a representation is "good enough" for our present purposes.

If current conditions are not related to past conditions or to future conditions then causation (a type of relation) is false so all of our reasons for believing things would be wrong. There would be no justification for anything and the basis for ethics and politics would be false — Harry Hindu

I agree that causation is a type of relation.

Between two objects in the world A and B we observe a spatial relationship - object A is to the right of object B. Because we observe a spatial relationship between A and B, it does not follow that in the world there is a something that exists between objects A and B independent of and in addition to the space between them, a thing called a "spatial relation" which exists as much as objects A and B.

Similarly, between two objects in the world A and B we observe a causal relationship - object A hits a stationary object B and object B moves. Because we observe a causal relationship between A and B, it does not follow that in the world there is a something that exists between objects A and B independent of and in addition to the interaction between them, a thing called a "causal relation" which exists as much as objects A and B.

For us to apply our reasoning and judgements, it is sufficient that spatial and causal relationships exist in our mind

In denying that relations have an ontological existence then you are implying that solipsism is the case. — Harry Hindu

Solipsism may be defined as the philosophical idea that only one's mind is sure to exist. As an epistemological position, solipsism holds that knowledge of anything outside one's own mind is unsure; the external world and other minds cannot be known and might not exist outside the mind.

Being an Indirect Realist, I believe the external world exists, but I don't know for certain. Isn't everyone a solipsist to some degree ?

To deny that relations have an ontological existence in the external world is not to deny that time, space, matter and forces don't exist. Why should the existence of an object in the external world depend on its being in an ontological relationship with something else ?

In rejecting dualistic notions of reality, I believe that minds and everything else are the same type of thing, which I identify as relationships, processes, or information. — Harry Hindu

If the mind and everything else, such as a table, are the same type of thing, are tables conscious ?

How is the "internal" contents of ypur mind different than the internal contents of say, your stomach? — Harry Hindu

I assume because my mind is conscious, but my stomach isn't.

Visually, you only perceive one side of the apple — Harry Hindu

Yes, as you say, "you can feel all sides of the apple even though you can't see all sides of the apple".

Because you cannot see the relationships on all sides of the apple, yet can feel the relationships on all sides of the apple, these missing relations must have originated in the mind, not the world.

This is a problem because other minds are external to yours. — Harry Hindu

It comes down to belief. As I believe that tables are not conscious, I believe that other minds are conscious. I may be wrong. I will never know for certain. It is just a working hypothesis.

In asserting that proto-consciousness is fundamental in the world, and that relations only exist in the mind, are you not admitting that relations exist in the external world? — Harry Hindu

I don't know for certain that proto-consciousness is fundamental in the world, and even if it is, it is still beyond my understanding, but it is the least implausible explanation that I have come across.

Yes, it would follow that if I believed in panpsychism this would lead me to concluding that relations ontologically exist in the external world, which is why I tend to protopanpsychism which doesn't require such a conclusion. -

Replies to Steven French’s Eliminativism about Objects and Material Constitution. (Now with TLDR)Bradley must be wrong. Because it would be a miracle if the human mind had relations and nothing else did. — Olivier5

Not unless there is truth in panprotopsychism.

In that event, there would be a world with proto-consciousness and without ontological relations, and a mind with consciousness and with ontological relations.

In the conscious mind, distinct objects are united by the relationship between them into a single experience (the binding problem). -

Replies to Steven French’s Eliminativism about Objects and Material Constitution. (Now with TLDR)If relations exist in the mind and not the external world, is the mind a miracle? — Olivier5

A miracle may be defined as "an extraordinary and welcome event that is not explicable by natural or scientific laws and is therefore attributed to a divine agency"

For me, not a miracle, as I am sure that the mind is explicable by natural or scientific laws.

However, even if there was someone to explain it to me, my understanding would probably be no more than that of a penguin trying to understand the foreign exchange market. -

Replies to Steven French’s Eliminativism about Objects and Material Constitution. (Now with TLDR)Bradley's Regress Argument against external relations..................So we already know that this reasoning must be faulty, since there would be no possibility of any reasoning if it was true — Olivier5

If Bradley is correct, and relations exist in the mind and not the external world, an observer of the apple and the tree will be aware of many relationships, such as - the apple is below the tree - the apple is smaller than the tree - the apple is more red than the tree - etc.

Given knowledge of these relationships, the observer will be able to exercise their powers of reasoning, for example - the apple is likely to have fallen from the tree - the apple has probably grown from the tree - the chemical composition of the apple as far as one can tell is different to that of the tree - etc.

Now what does it mean "to be something to them"? — Olivier5

It means that relation R relates a to b

The tree or the apple are obviously not expected to know something about their respective position — Olivier5

Of course, as trees and apples have no minds. But what is the case is that there is no information within the tree that relates it to the apple, and vice versa.

Still, their respective position remains an objective fact. — Olivier5

"Respective" is defined as "belonging or relating separately to each of two or more people or things". You are starting off with the premise that relationships in the external world are objective facts. Bradley is giving a justification as to why relationships in the external world are not objective facts.

It looks to me that either he is projecting intentionality on mindless thing — Olivier5

Bradley refers to things, not minds -

Replies to Steven French’s Eliminativism about Objects and Material Constitution. (Now with TLDR)Is not the mind part of the world? — Harry Hindu

Yes, I should have written: "relations do exist, but in the mind, not in the external world". I agree that the mind is part of the world, having evolved in synergy with the world, possibly over a period of 800 million years.

Steve French is misusing the term eliminativism (it seems to me).

Steve French relates eliminativism to objects in the world, such as tables. However, in philosophy, eliminativism is a theory about the nature of the mind, not about the nature of the external world.

IE, within his article he should have used the term reductionism when referring to tables.

Where do relations exist, if they do exist.

For me, there is a mysterious difference between the mind and "external world", in that, although I believe that relations don't have an ontological existence in the external world, I do believe that relations have an ontological existence in the mind.

As regards the mind of the observer, I know that I am conscious. I know that I have a unity of consciousness, in that what I perceive is a single experience. John Raymond Smythies described the binding problem as "How is the representation of information built up in the neural networks that there is one single object 'out there' and not a mere collection of separate shapes, colours and movements? I can only conclude, from my personal experience, that relations do have an ontological existence in my mind, such that when I perceive an apple, I perceive the whole apple and not just a set of disparate parts.

IE, relations do exist, but in the mind, not in the external world.

Reductionism and eliminativism

Slightly back-tracking, I am reductionist as regards the "external world" and non-eliminativist as regards the mind. I feel that I can justify my belief in being a reductionist as regards the external world, but the binding problem is my only justification for my belief in non-eliminativism as regards the mind. My understanding of the unity of consciousness is as much as a goldfish's understanding of the allegories in The Old Man and The Sea.

IE, I would still argue that being a reductionist as regards the external world is a justified true belief.

How can the mind be part of the world

The question is how to equate being reductionist about the external world and non-eliminativist about the mind. My answer is panprotopsychism, in that a proto-consciousness is fundamental and ubiquitous in the world. This allows the mind to be part of the world, as well as allowing monism whilst avoiding the problems of dualism. Using an analogy (not an explanation), as the property of movement cannot be observed in a single permanent magnet, but only in a system of permanent magnets alongside each other, the property of consciousness cannot be observed in the physicalism of the external world, but only in a system of neurons having a particular arrangement within the brain.

IE, still keeping within physicalism and monism, the mind as a system has properties, such as consciousness, not observable in its individual parts, analogous to the property of movement in a system of permanent magnets not being observable in an individual permanent magnet, one of several examples of the weak emergence of new properties. -

Replies to Steven French’s Eliminativism about Objects and Material Constitution. (Now with TLDR)Therefore if relations do not exist, texts do not exist either. — Olivier5

When I, as an observer, look at the page, I agree that the symbol "i" physically exists on the page and the symbol "f" physically exists on the page to the right of the symbol "i", in that they are spatially located.

Along the lines of Bradley, there is no information within the symbol "i" that there is a symbol "f" to the right of it. Similarly, there is no information within the symbol "f" that there is a symbol "i" to the left of it, and there is no information in the space between the "i" and the "f" that there is a "i" at one end and a "f" at the other end.

It follows that the meaning of the shape "if" does not exist in the world.

The shape "if" only has meaning in the mind of an observer, as only an observer can turn the relationship between the "i" and the "f" into a meaning.

IE, relations do exist, but in the mind, not the world. -

Replies to Steven French’s Eliminativism about Objects and Material Constitution. (Now with TLDR)Amazon.........They sell tables too. — Olivier5

:smile: Very true, tables must exist if Amazon sells them. Forget the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy,

perhaps Amazon is where we will discover the answers to our deepest philosophical questions. -

Replies to Steven French’s Eliminativism about Objects and Material Constitution. (Now with TLDR)Before doing so, are you satisfied that Bradley himself existed ontologically? And if yes, what makes you so sure? — Olivier5

Because Amazon sells his books. -

Replies to Steven French’s Eliminativism about Objects and Material Constitution. (Now with TLDR)two particles in the same universe can interact with one another — Olivier5

I agree that "two particles in the same universe can interact with one another". But as you said "So the challenge is to prove that relations do exist "ontologically". That is to say (I guess) that they exist objectively "out there", and not just as ideas in our minds."

Steve French argues against non-eliminativism, where non-eliminativism is the position that the whole is more than the sum of its parts, possibly because there are ontologically real relations between the elementary particles making up the whole.

I go back to Bradley's Regress Argument against external relations (SEP - Relations), which concluded that we should eliminate external relations from our ontology.

Either a relation R is nothing to the things a and b it relates, in which case it cannot relate them.

Or, it is something to them, in which case R must be related to them.

But for R to be related to a and b there must be not only R and the things it relates, but also a subsidiary relation R' to relate R to them

Now the same problem arises with regard to R'. It must be something to R and the things it related in order for R' to relate R to them and this requires a further subsidiary relation R'' between R', R, a and b.

This leads into an infinite regress, because the same reasoning applies to R' and to however many other subsidiary relations are subsequently introduced.

IE, particles will still interact even if relations are only spatial and not ontological. -

Replies to Steven French’s Eliminativism about Objects and Material Constitution. (Now with TLDR)Do note that these particles exist in the same universe. Therefore they are already in a relation with one another, a spatial relation: they share the same space. Now you could say that this is a purely conceptual relation, not an ontic one. But if that is the case, then space does not exist ontologically. — Olivier5

I don't understand why there couldn't be a space that exists independently of any human observer within which there are particles that are, as you said, "entirely alone" (ignoring for the sake of the argument any forces between the particles).

Using an analogy, if there is a cat in a box, it does not follow that because the cat is entirely alone there is neither a cat nor a box. -

Replies to Steven French’s Eliminativism about Objects and Material Constitution. (Now with TLDR)I agree with @Olivier5 that the question is "do relations exist objectively "out there", and not just as ideas in our minds"

Using particle to also mean elementary particle.

Particles ontologically exist in the world

Materialists historically held that everything was matter, but we now know that not everything is matter in this historical sense, for example, forces such as gravity are physical but not material in the traditional sense. As the world exists, at least particles exist.

If relations ontologically existed in the world

If relations ontologically existed in the universe, then between any two particles in the universe there is a relationship that ontologically exists. For example, it follows that between a particular particle in the table in front of me and a particular particle somewhere in the Andromeda Galaxy there is a real ontological relationship.

One could ask if the relationship between two particles is limited by the speed of light or is instantaneous across the universe.

Do relations ontologically exist in the world

Consider two particles A and B. Each particle A and B has an ontological existence.

The question is, does the relation AB between the particles A and B have its own ontological existence in addition to the ontological existence of each particle ?

The problem for an observer is in recognizing the ontological existence of the relation, in that a world with ontological relations between ontological particles would be indistinguishable from a world only consisting of ontological particles. What purpose do ontological relations serve ?

As the human observer uses their mind to add relationships between observed particles, the existence of relations ontologically existing in the world serves no purpose, and if they serve no purpose, by Occam's Razor, it should be assumed that they don't exist.

So the challenge is to prove that relations do exist "ontologically"................A chemist would answer yes to this question — Olivier5

I agree that the concept of the world implies interconnectivity between the elements of the world, but concepts exist in the mind, not the world. Elementary particles located in time and space are sufficient for a world to exist. A world with ontological relations between these particles would be indistinguishable from a world without ontological relations between these particles, meaning that ontological relations serve no purpose. And if they serve no purpose, why have them.

I agree there may be forces between particles, there may be forces between oxygen and hydrogen atoms, but forces are not the same thing as relations ontologically existing in the world.

relations do have ontological existence... Ryle and anyone who has written about category mistakes for the last 70 years — Cuthbert

Ryle's examples are based on examples whereby relations exist in the mind, not the world.

Ryle gave examples of category mistakes in The Concept of Mind 1949.

A visitor to Oxford upon viewing the colleges and library reportedly inquired "But where is the University".

There is the category 1 of "units of physical infrastructure", and category 2 of "institution"

The visitor made the mistake of presuming that the "University" was part of category 1 rather than category 2.

Category 1 includes those parts that physically exist in the world independent of the visitor - colleges, library, etc. Category 2 includes unseen relations between those physical parts - role in society, laws and regulations, etc

Ryle's examples make use of the fact that relations don't exist in the world but do exist in the mind, supporting the idea that relations don't have an ontological existence in the world. -

Replies to Steven French’s Eliminativism about Objects and Material Constitution. (Now with TLDR)how to reply to an argument Steven French makes below. — Ignoredreddituser

A whole is a particular relation between its parts, in that a table is a particular relation between its atoms. If the whole is more than the sum of its parts, then relations must have their own ontological existence over and above the ontological existence of the parts (putting to one side the question of what exactly is a part).

To argue against Steven French and argue for the non-eliminativist view, one will also need to argue that relations ontologically exist.

As the SEP on "Relations" notes: "Some philosophers are wary of admitting relations because they are difficult to locate. Glasgow is west of Edinburgh. This tells us something about the locations of these two cities. But where is the relation that holds between them in virtue of which Glasgow is west of Edinburgh? The relation can’t be in one city at the expense of the other, nor in each of them taken separately, since then we lose sight of the fact that the relation holds between them (McTaggart 1920: §80)"

I know that Glasgow is west of Edinburgh, but does Glasgow know that it is west of Edinburgh !

IE, the non-eliminativist must also argue for the ontological existence of relations - not an easy task. -

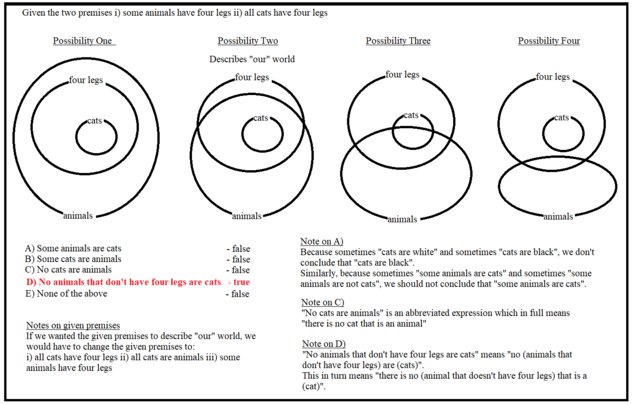

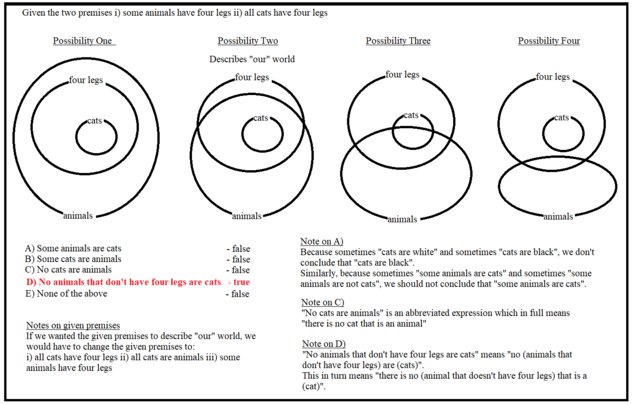

Help With A Tricky Logic Problem (multiple choice)In what the OP said, I have replaced "Ayes" with "animals", "Bees" with "four legs" and "Seas" with "cats". All the rest is the same. The conclusion (D or E) is what the OP also thought (maybe for another reason though). — Alkis Piskas

I have redrawn my Venn Diagram, including @Raymond and @tim wood's suggestions, and using animals, etc rather than Ayes, etc. The solution is still D.

-

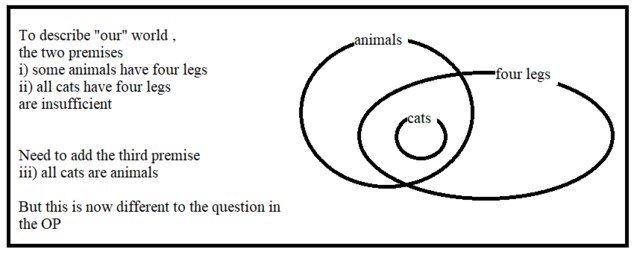

Help With A Tricky Logic Problem (multiple choice)However, I'm not sure about the left drawing. It doesn't show that mammals are a subset of animals. It shows that only a part of mammals are also animals. — Alkis Piskas

I agree that the left hand drawing is not correct for "our" world, where i) all mammals are animals (all B's are A's) ii) all cats are mammals (all C's are B's)

But the OP is not asking a question about "our" world. The OP is asking a question about a "possible" world, perhaps a fictional world, where i) some animals are mammals (some A's are B's) ii) all cats are mammals (all C's are B's), in which case the left hand drawing is correct.

RussellA

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum