-

What is a painting?I think it's more that naming helps fix the mind on something, and remember it. If your visual field is filled with color, you'll remember the aspects of it that you have associated with a name. — frank

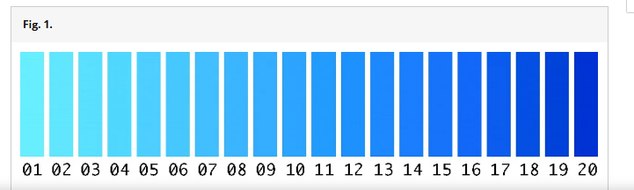

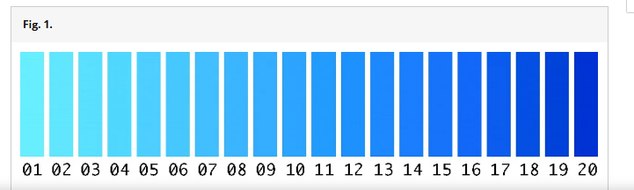

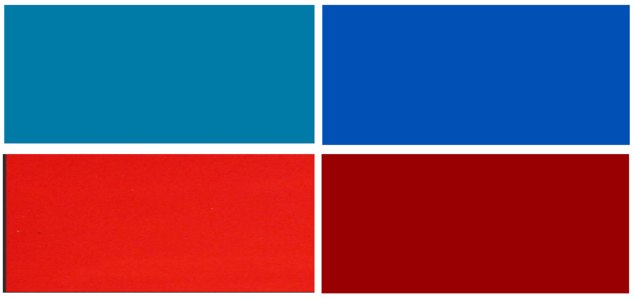

True, but you don't need to know the names of the colours 1 to 20 in Fig 1 in order to see them. -

What is a painting?"more extensiveness", whatever that might mean — Moliere

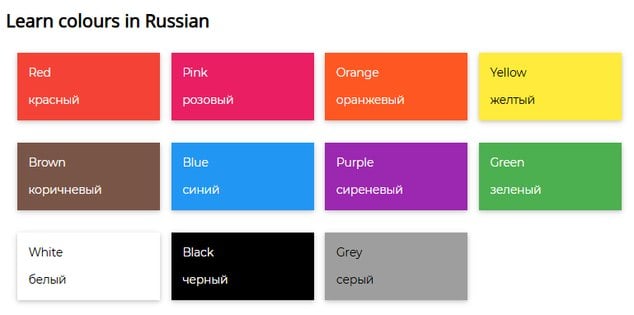

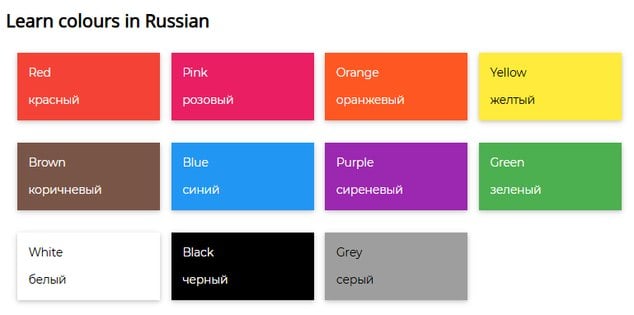

For example, English has a word for "blue" that the Russians don't seem to have.

It seems in general that English has a larger vocabulary than Russian, possibly because many English words were borrowed from Latin, French and German.

How many words are there in the Russian language?

There are many estimates. However, several of the larger Russian dictionaries quote around 130,000 to 150,000. Now, that’s a lot of Russian words. But if you compare it to English for instance – which has more than 400,000, then it’s not that bad. -

What is a painting?Isn't it interesting that they have two distinct words for what we'd call "the same"? — Moliere

The relationship between category and concept is interesting.

It seems that the Russians don't have one word for blue but have one word for pale blue голубой and one word for dark blue Синий. However, in English, we also have two distinct words, ultramarine for dark blue and cerulean for pale blue.

It seems that English is more extensive than Russian in that we also have a word for "blue", which the Russians don't seem to.

As regards the copula, "ultramarine is blue" and "cerulean is blue".

This is the beginning of categorization. Violet is a visible colour, blue is a visible colour, cyan is a visible colour, green is a visible colour, yellow is a visible colour, orange is a visible colour and red is a visible colour. Visible colour can then be categorized into violet, blue, cyan, green, yellow, orange and red.

Ultramarine is not the same as cerulean. Ultramarine is not the same as blue. The word "same" is not used as a copula, as a copula connects two different things.

Each of these is also a pre-language concept in that we don't need to know the names "violet" and "blue" in order to be able to discriminate between violet and blue.

It is the fact that we are able to discriminate between violet and blue, as we are able to discriminate between pain and pleasure, that enables us to develop a language that is able to categorise these discriminations.

It would indeed be strange if we could only perceive those things in the world that we happen to have names for. It would mean that if we had no name for something, then we couldn't perceive it, and if we couldn't perceive it then we couldn't attach a name to it. -

What is a painting?It's explicitly about both. — Jamal

The introduction to the article writes that they are investigating discrimination between colours, not the perception of colours

We investigated whether this linguistic difference leads to differences in colour discrimination.

Though of course, in order to be able to discriminate between colours 1 to 20 in Fig 1 they first they must be perceived. But this is not the topic of the article.

Kant's pure intuitions of time and space and pure concepts of understanding (the Categories) are not linguistic. The article is about linguistic discrimination. -

What is a painting?Yes, Синий and голубой are basic colour terms and are thus seen as basic colours, not as shades of the same colour....The difference is that we think of ultramarine and cerulean as shades of blue, since in English that's what they are. — Jamal

The article "Russian blues reveal effects of language on colour discrimination" is about how people discriminate colours, not about how people perceive colours.

The article points out that in Russian there is no single word for the colours seen in Fig 1, and asks whether this means that Russians discriminate colours differently from non-Russians.

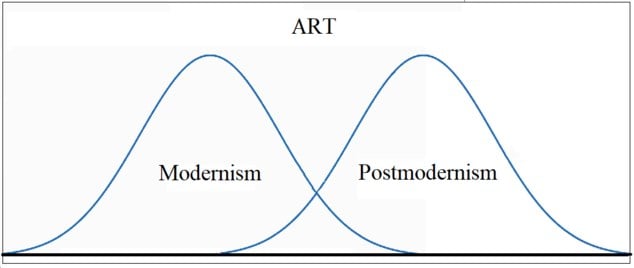

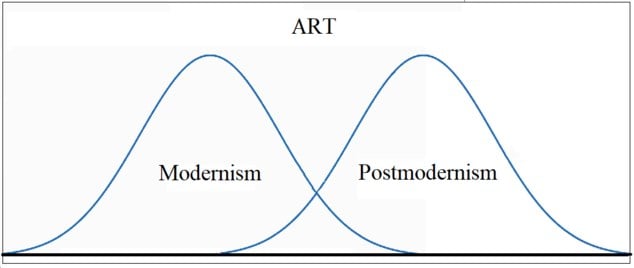

It seems certain that language does affect how people discriminate not only colours but observations in general. For example, someone looking at various artworks who is not aware of the concepts Modern and Postmodern will certainly categorise these artworks differently to someone who has learnt the concepts Modern and Postmodern.

It should be noted however that even through the Russian may not have a single word for the colours in Fig 1, and make the distinction between lighter blue голубой and darker blue Синий, this is a similar approach to English that makes the distinction between cerulean blue and ultramarine blue.

Again, because a linguistic distinction has been made between colours, it does not follow that there is a perceptual distinction. For example, an observer's perception of colour 9 in Fig 1 doesn't change as its name changes. An observer perceives the same colour regardless of whether it is called голубой in Russian, cerulean in English, bleu pâle in French or azzurro pallido in Italian.

The article notes that categories in language affect performance on simple perceptual colour task. This is understandable, in that someone not aware of the concepts Modern and Postmodern when looking at artworks and when asked to make judgements about these artworks will perform differently to someone who is aware of the concepts Modern and Postmodern.

These results demonstrate that (i) categories in language affect performance on simple perceptual colour tasks and (ii) the effect of language is online (and can be disrupted by verbal interference).

The article also concludes that performance can be disrupted by verbal interference. Also understandable, in that is someone was told that a particular artwork was an example of Modernism when in fact it was an example of Postmodernism, their immediate, instinctive judgment about the artwork would clearly be disrupted.

There is the strong and weak version of the Whorfian hypothesis. In linguistics, the Whorfian hypothesis states that language influences an observer's thought and perception of reality, and is known as linguistic relativity. The strong Whorfian hypothesis suggests that language determines a speaker’s perception of the world. The weak versions of the hypothesis simply state that language influences perception to some degree. The strong version has now been largely rejected by linguists and cognitive scientists, especially with the development of Chomskyan linguistics, although the weak version remains relevant. The weak version does allow for the translation between different languages.

https://www.britannica.com/science/Whorfian-hypothesis.

Speakers of different languages can look at colour 9 in Fig 1 and perceive the same colour regardless of its name. They are able to perceive the colour with the "innocent eye" described by Ruskin. He wrote that it is not the case that we can only perceive something if we already know what it is. This would inevitably lead into an infinite regression of perception and knowledge.

This is in opposition to Gombrich who argued that there is no "innocent eye". He wrote that it is impossible to perceive something that we cannot classify, thereby supporting the strong Whorfian hypothesis. But today the strong Whorfian hypothesis is generally not accepted. It it were accepted, it would lead into another chicken and egg situation, in that we couldn't even perceive colour 9 without knowing its name, and we couldn't know its name until we have perceived it.

The article makes sense that categories in language do affect a person's performance, but this is not saying that categories in language affect a person's perceptions. -

What is a painting?Habit actually configures highways through the nervous system, so maybe language (not just the syntax, but the whole history and emotional anchoring) influences what a person is conscious of. — frank

Language does affect what a person is conscious of.

Count how many times the players wearing white pass the basketball -

What is a painting?But pain is not art, nor is it an interpretation of an object's aesthetic elements. So there's a problem with that comparison. — Tom Storm

Though the experience of pain and the aesthetic experience are both subjective feelings, and both exist in the mind rather than the world.

===============================================================================

By your reckoning, all we're doing is looking at shapes and colours, without context, composition, and experience. That strikes me as a very limited conception of aesthetics. If one did this to a work by Caravaggio where would we get? — Tom Storm

Take away all the shapes and colours from Caravaggio's "Boy Peeling Fruit" c. 1592-1593 and what would remain?

As Clive Bell said, it is the Significant Form of these shapes and colours that establishes the aesthetic.

==============================================================================

Going back to pain for a moment, in a hospital, one of the first questions asked is, "On a scale of one to ten, how much does it hurt?" This reveals that pain alone isn’t self-interpreting; we need language and description to give it meaning, to locate it within a framework that allows for understanding, assessment, and response. — Tom Storm

I walk into my house holding my hand and looking for antiseptic after being stung by a wasp.

I am carried into a hospital after being run down by a car and screaming in pain.

Language is not needed to distinguish the level of pain on a scale from one to ten. -

What is a painting?If you actually take on board what I said, which is that Russians (Russian speakers) do not see light blue and dark blue as shades of the same colour, then you will understand why this is the case — Jamal

Are you saying:

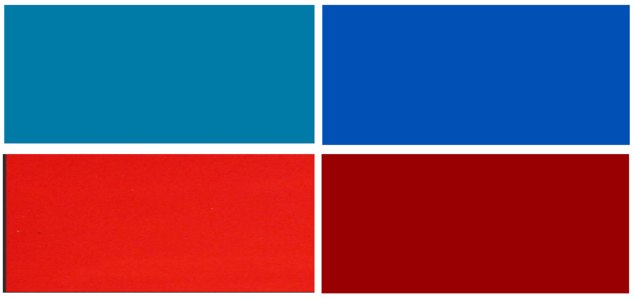

1) Russians don't see light blue and dark blue as shades of the colour blue. I would be surprised if Russians saw colours differently to non-Russians.

2) Russian speakers have Russian words for "light blue" and "dark blue", and these Russian words don't make any reference to being part of the same colour "blue". But this applies to English also, in that neither ultramarine nor cerulean refer to the colour blue. -

What is a painting?Sure, you can see cadmium blue without knowing the name, but you only recognise it as cadmium blue (or see it as meaningful) because you’ve learned to see it that way and have been given a name. Otherwise, it’s just part of a blur of unfiltered input. — Tom Storm

Perhaps we are too far apart on this matter.

Replacing "cadmium blue" by "pain"

Sure, you can feel pain without knowing the name, but you only recognise it as pain (or see it as meaningful) because you’ve learned to see it that way and have been given a name. Otherwise, it’s just part of a blur of unfiltered input.

I would have thought that our subjective feeling of pain was independent of language. In other words, does knowing the name of our pain change the subjective feeling? -

What is a painting?No. Russians don’t. Some pairs of hues are closer together than others, but the rest is preconceptions. — Jamal

I have never been to Russia, but they seem to have the word синий

What does синий mean?

https://linguapedia.info/en/russian/vocabulary/colours -

What is a painting?To begin with, an innocent baby doesn’t know what colours are or what they’re called. They need to be socialised and taught colour, just as they are taught shapes, and patterns and even their meanings and uses (e.g., 'blue for boys, pink for girls'). — Tom Storm

When stung by a wasp, you don't need to know the name "pain" before feeing pain. You feel pain regardless of what it is called.

Similarly with seeing colour, you don't need to know the name "cadmium blue" before seeing cadmium blue.

Similarly with having an aesthetic experience, you don't need to know the name "aesthetic experience" before having an aesthetic experience.

You need a name in order to communicate your subjective experience with other people, but you don't need a name to have that subjective experience. -

What is a painting?Do you see light blue and dark blue as shades of the same colour? — Jamal

Yes. Doesn't everyone.

The top two colours have a family resemblance, and as members of the same family are similar but not identical.

-

What is a painting?The ultimate "innocence," which I'm arguing is an impossible limit-case, would have you looking at the Lascaux painting from a kind of "view from nowhere" — J

This "innocence" is common in human cognition.

For example, when I look at grass, I don't think to myself, what colour should I see this grass as, should I see it as yellow, red, green or purple. I don't approach seeing colours with any preconceptions. In seeing the colour of an object my approach is no different to that of an innocent baby. I see the colour I see.

Similarly, with seeing an aesthetic in an object.

===============================================================================

Are you saying that your own cultural and individual experience of art, which you bring to the Fauve painting, has no effect on your perception of "great aesthetic value"? — J

Yes.

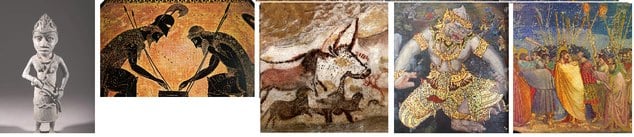

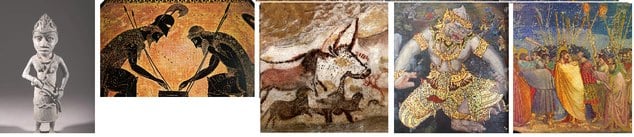

My belief is that every society in the past 17,000 years would recognise the aesthetic value in the Lascaux cave paintings. From the Sumerians through the Minoans up to the Greeks, Romans and into the 21st C, regardless of their particular religious, political or cultural beliefs.

===============================================================================

I think you're wanting to say that the painting contains, in and of itself, aesthetic value? — J

No.

"Beauty is in the eye of the beholder"

The object does not contain aesthetic value. The object contains a certain form in which an observer can see an aesthetic. -

What is a painting?There’s plenty of postmodern art created by graduate artists and unknown, underexposed, even struggling artists who see in postmodernism a vitality and opportunity for expression that you or others may not. — Tom Storm

I agree that postmodern art is an opportunity for expression. I think less through the physical object but more through accompanying statements.

These unknown, underexposed postmodern artists, what exactly are they struggling against?

It seems that they are struggling to break into the Artworld, which is, as I see it, an exclusive club rather than a democratic institution. -

What is a painting?My list of what constitutes an innocent eye was partial, but taking it as a starting point, do you feel that, when you encounter one of the above artworks (which are extraordinary, by the way, thanks!) you:

- know nothing about it? Really??

- know nothing about art yourself, from your own culture?

- are able to encounter the art in a way that is separate from a time and place?

- bring no cultural or individual experience to bear? — J

There are two distinct, separate and independent aspects.

On the one hand, there is the object as it exists independent of what one knows about it, and on the other hand there is what one knows about the object.

There is the object, for example a Lascaux cave painting.

There is what one knows about it. Estimated at around 17,000 to 22,000 years old, painted by the Magdalenian peoples, reindeer hunters who possibly engaged in cannibalism.

That the the object was possibly painted by a reindeer hunter has no bearing on the aesthetics of the object. The object has an aesthetic value regardless of whether it was painted by a reindeer hunter or a plant gatherer.

It is true that I know something about the Lascaux cave paintings, I know something about the Fauve artists of the 20th C and I have a particular cultural and individual experience, but all these have no effect on my seeing an object that has great aesthetic value.

In discovering an aesthetic in the Lascaux cave painting, my eye is innocent of any knowledge of facts and figures. -

What is a painting?There is no such thing as an art work without an "accompanying statement.....................................Is there anyone on this thread who disagrees that this is a fiction? — J

I know that these images have an aesthetic and are therefore art without knowing anything about the cultures they originated in.

The beauty of the aesthetic in art is that the observer only needs an innocent eye.

One problem with Postmodernism is that depends on its existence through the promotion of elitism within society, an incestuous Artworld that deliberately excludes the "common person" in its goal of academic exclusivity. -

What is a painting?I guess that's why we have critics... But I'd imagine the statement is part of the artwork. — Tom Storm

Copilot agrees "In Postmodernism, the boundary between the artwork and its accompanying statement is often deliberately blurred."

In that event, even though there may minimal aesthetic in the physical object, such as a pebble, there may be substantial aesthetic in the accompanying statements, whether by the artist, gallery or critic.

So overall, if a Postmodern artwork includes both the physical object and accompanying statements, there may well be substantial aesthetic in a Postmodern artwork.

That is why the physical object in a Postmodern artwork may be either minimal or imagined. In other words, conceptual. The concept in a Postmodern artwork is more important than any physical object.

The aesthetic is in the thoughts initiated by a real or imaginary object rather than the object itself. -

What is a painting?As long as we recognise that the hierarchy is man-made......................................The difference isn’t in the objects themselves, but in the interpretive habits we've inherited. — Tom Storm

Exactly my thoughts.

===============================================================================

But since I'm sympathetic to postmodernism and you're not, maybe we won't get passed this. — Tom Storm

Though have sufficient interest to have been to the Venice Biennale.

I have a question.

Suppose the Postmodern artwork is a single pebble in the Whitechapel accompanied by a statement by the artist.

Is the "artwork" just the pebble or is the "artwork" the pebble plus the accompanying statement by the artist? -

What is a painting?I’m saying that when an artist presents something as art, it’s an invitation to explore it aesthetically.............................But yes, more broadly, our experience of the world may also be largely aesthetic......................The aesthetic goes beyond art: our sensory and perceptual engagement with the world is aesthetic in nature. — Tom Storm

Totally agree.

As you say "It's pretty easy to say that a cel from a Bugs Bunny cartoon is less 'important' as art than a Rembrandt". There is a hierarchy in the importance as art of an object.

Similarly, it seems clear that there is also a hierarchy in the aesthetic of an object. For example, I am sure that most would agree that the aesthetics in the object that is Leonardo's painting "The Last Supper" are higher than the aesthetics in the object that is a straight line.

In other words, it is not the case that an object is either art or not art, or an object is either aesthetic or not aesthetic

Every object can be thought of as art and having an aesthetic, though some objects are more artistic or more aesthetic than other objects.

===============================================================================

How do you define an aesthetic experience? — Tom Storm

In words, I would agree with Francis Hutcheson's approach:

For Hutcheson, beauty is not in the object but is in how the object is perceived, and stems from uniformity amidst variety. Diverse elements come together in a way that feels balanced and harmonious, a dynamic process where we sense order within complexity.

The ability to discover patterns in chaos (ie, an aesthetic) is an important part of human cognition.

However, as with other aspects of human cognition, there are limits to any explanation.

For example, when you look at grass, why do you perceive the colour green rather than the colour blue. Any deep explanation is beyond current scientific or philosophical understanding.

Similarly, when one looks at "The Last Supper" and a straight line and have a greater artistic and aesthetic experience with "The Last Supper" than the straight line, any deep explanation is beyond current scientific or philosophical understanding.

I could say that "The Last Supper" is more complex than a straight line, but this raises the question, why is something more complex of necessity either more artistic or more aesthetic, to which there is no answer.

For me, an object is aesthetic if I discover within it a unity within variety, in the same way that I discover greenness in grass. -

What is a painting?Jeff Koons is a postmodern artist. How is his work not an invitation to have an aesthetic experience?.................................But since you raised it - an experience is aesthetic when we pay attention to how it feels, looks, or affects us, not just what it does. Drinking coffee becomes aesthetic when we enjoy its taste, smell, and warmth. Sitting on a hard chair can be aesthetic if we notice how it feels and how it makes us sit. It’s about noticing and appreciating the experience, not just using it for a purpose. — Tom Storm

You are saying that we have an aesthetic experience when we are aware of having a feeling. This feeling may be pleasant, such as drinking coffee, or unpleasant, such as sitting in a hard chair.

For example, you say that if we have feelings towards a Jeff Koons artwork, then we are having an aesthetic experience.

You seem to be saying that all our feelings are aesthetic experiences.

However, this is not how the word is generally used. I am sure I am correct in saying that as the word is generally used, some feelings may be aesthetic experiences and some feelings may not be aesthetic experiences.

If that is the case, Jeff Koons, as a Postmodern artist, may be inviting the observer to have a feeling towards his artwork, but it does not follow that this feeling must be aesthetic.

===============================================================================

Sounds like you have a hierarchy of what counts as art, or maybe just what counts as good art?............................. It's pretty easy to say that a cel from a Bugs Bunny cartoon is less 'important' as art than a Rembrandt. — Tom Storm

We agree that there is a general hierarchy in art from the more important to the less important. For example, a Bugs Bunny cartoon is less important as art than a Rembrandt. Though of course the particulars may be argued over. For example, is a John Osborne play more or less important as art than a Arthur Miller play? -

What is a painting?In short, it takes more than "someone" to successfully place a pebble as art in the Whitechapel Gallery. Who else is needed, and what is that context? This is where so-called institutional theories of art start to gain traction, I think. — J

Yes, that person has to be a member of the pre-existing Artworld, a loose collection of art institutions, artists, critics, curators, art teachers, auction houses and wealthy collectors.

https://fromlight2art.com/institutional-art-theory-explained/

Postmodernism is an example whereby the word "art" has been given a new meaning by this Artworld. As you say, the Institutional Theory.

For someone to place a pebble as art in the Whitechapel Gallery, they would have to "play the game". This may take a few years, but is possible. For example, they could become an art teacher at St Martins School Of Art, submit articles to Art Quarterly, hire a gallery in Shoreditch to exhibit their own conceptual works, volunteer for DACS in order to get to know Gilane Tawadros and perhaps submit to the Venice Biennale.

A fair amount of work, but not everyone gets to see their very own pebble in one of London's most prestigious Postmodern Art Galleries. -

What is a painting?All postmodern art has some kind of aesthetic. It doesn’t have to be about beauty; rather, like any work, it’s an invitation to experience something aesthetically. To experience something aesthetically means to engage with it through your senses and perception, paying attention to its qualities: form, texture, colour, tone, or atmosphere. And the work's conceptual and cultural context. It’s about how the artwork affects you emotionally, intellectually, or even physically, whether through pleasure, discomfort, curiosity, or reflection. — Tom Storm

I agree that aesthetics is more than beauty, and can includes the beauty of a Monet "water lilies" and the ugliness of a Picasso "Guernica".

I agree that an observer engages with a Postmodern artwork through their senses and perception, but this does require the artwork to be aesthetic.

An observer of a Postmodern artwork may pay attention to its qualities: form, texture, colour, tone, or atmosphere, but again this does not require the artwork to be aesthetic.

An observer of a Postmodern artwork may pay attention to its conceptual and cultural context, but this does not require the object to be aesthetic.

An observer of a Postmodern artwork may be affected emotionally by looking at it, but in what way is anger aesthetic?

An observer of a Postmodern artwork may be affected intellectually by looking at it, but in what way is knowing that grass is green aesthetic?

In what way is the pleasure of drinking a cup of coffee aesthetic?

In what way is the discomfort of sitting on a hard chair aesthetic?

In what way is being curious about where foxes have their den aesthetic?

In what way is reflecting on what happened yesterday aesthetic?

Of course, you may be defining every object that causes an emotional feeling or intellectual thought as having an aesthetic. But if that were the case, every possible object in the Universe would have an aesthetic. But I don't think that is how the word is used.

===============================================================================

Sounds like you have a hierarchy of what counts as art, or maybe just what counts as good art? — Tom Storm

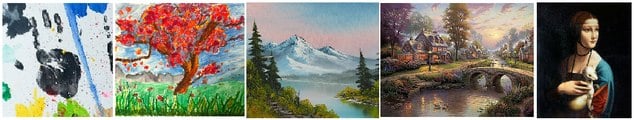

I find it impossible to believe that most people don't accept that there is a hierarchy in art. Is there anyone who would try to argue that the quality of a Bob Ross painting is equal to the quality of a Leonardo da Vinci painting?

-

What is a painting?Are you proposing this as context-free? Or does the object need to be presented in some way as to invite such a response? If so, what might be the context? — J

The context of the object is relevant. A pebble on a beach never seen or imagined by anyone cannot be a Postmodern artwork. For someone to take that pebble off the beach, display it in the Whitechapel Gallery, and accompany it with the statement that the pebble represents the anguish of the individual within a capitalist society, then it has become a Postmodern artwork.

In fact, the pebble does not even need to be taken off the beach. A photograph or video of the pebble may be displayed in the Whitechapel Gallery. Or even there may be a video of someone in the Whitechapel Gallery saying that they have seen a pebble on a beach.

===============================================================================

(I think this question applies to conceptual art as well -- not sure what you're including with "post-modern") — J

I include Conceptual Art within Postmodernism.

From the Tate:

As an art movement postmodernism to some extent defies definition – as there is no one postmodern style or theory on which it is hinged. It embraces many different approaches to art making, and may be said to begin with pop art in the 1960s and to embrace much of what followed including conceptual art, neo-expressionism, feminist art, and the Young British Artists of the 1990s. -

What is a painting?I rate conceptual art as aesthetic, like any other art, because it engages our senses, and invites emotional and/or intellectual responses. — Tom Storm

As it is said "Beauty is in the eye of the beholder".

An aesthetic may be defined as there being a unity in variety, a pattern in chaos.

Such an aesthetic might be discovered by a human observer in any observed object, whether architecture, dance, science, theatre, philosophy, literature, politics, art and nature.

As a first approximation, the Modernist artist deliberately creates an object in which an aesthetic may be discovered by a human observer. The Postmodernist artist, as a reaction against Modernism, deliberately creates an object minimising any aesthetic.

However, alongside a Postmodern artwork there may be accompanying descriptive text, either by the artist or commentator. As such accompanying textual description is not attached to the artwork, it cannot be considered to be part of the artwork.

As an aesthetic is deliberately minimised in Postmodern artworks, the observer might not discover any aesthetic within them, although they may discover an aesthetic in any accompanying descriptive text.

In summary, an aesthetic is not part of a Postmodern artwork, athough may be discovered in an accompanying descriptive text.

Postmodern art is diverse and self-aware, tends to use irony and blurring of categories to challenge traditional ideas of originality, meaning, and distinctions between high and low culture. It often appeals to people who like puzzles, gimmicks, statements and ambiguities. — Tom Storm

I don't disagree with your description of Postmodernism, but none of the terms used requires an aesthetic. For example, something may be diverse without being aesthetic.

As regards language, it is nature of language that there is a spread of meaning in a term, and it may well be the case that the meaning of two different terms may overlap.

-

What is a painting?Postmodernist artworks certainly don't lack pragmatic function or practical purpose.

Feminist artists worked to create a different cultural narrative that gave women a place to be heard where they could express themselves through their art and engage with the world through encouraging various social and political conversations.

https://artincontext.org/feminist-art/ -

What is a painting?Well, I don’t think art is about beauty. I think it’s about evoking an aesthetic experience in a particular context; one shaped by culture, intention, and the viewer’s own perspective. Beauty might be part of it, but it’s not the point. — Tom Storm

I agree. That is why I wrote on page 6

Modernism

It only becomes an artwork if the human responds to the aesthetics of the object. Note that an aesthetic response can be of beauty, such as Monet's "Water lilies", or can be of ugliness, such as Picasso/s "Guernica".

Postmodernism

It only becomes an artwork if the human responds to the object as a metaphor for social concerns.

In what sense is conceptual art intended to be aesthetic? -

What is a painting?Is this right? Can't utilitarian objects also be understood as art? Think of works by William Morris, for example, or Greek Attic vases. And then there’s conceptual art. — Tom Storm

Yes, an object may be both beautiful and utilitarian, such as William Morris wallpaper. But these properties are independent of each other. The beauty of the wallpaper does not affect its function of covering over a wall, and it fulfils its function of covering over a wall whether or not it is beautiful.

A utilitarian object can also be artistic, but a utilitarian object doesn't need to be beautiful in order to be utilitarian.

Conceptual art is part of Postmodernism and Postmodernism specifically excludes the beautiful in its rejection of Modernism.

In what sense is conceptual art intended to be either beautiful or utilitarian? -

What is a painting?What is an artwork?

A Modernist artwork may be defined as any object real or imagined that has no utilitarian purpose that has been observed or thought about by a human as an aesthetic, which is about a sense of order within complexity.

A Postmodernist artwork may be defined as any object real or imagined that has no utilitarian purpose that has been observed or thought about by a human as a metaphor for social concerns, which is about the collapse of grand narratives leading to plurality and fragmentation.

Modernism and Postmodernism

Step one. Any object real or imagined, such as a hammer or Voldemort

But, objects like hammers are thought of as utilitarian rather then art. Therefore remove any utilitarian purpose to the object and just consider the hammer in the absence of having any purpose

Step two. Any object real or imagined that has no utilitarian purpose

But, if such an object has never been observed or thought about by a human it can never be an artwork

Step three. Any object real or imagined that has no utilitarian purpose that has been observed or thought about by a human

But, even so, this doesn't mean that the human observing or thinking about the object treats it as an artwork.

From now, there are two different directions, Modernism and Postmodernism.

Modernism

It only becomes an artwork if the human responds to the aesthetics of the object. Note that an aesthetic response can be of beauty, such as Monet's "Water lilies", or can be of ugliness, such as Picasso/s "Guernica".

Step four. Any object real or imagined that has no utilitarian purpose that has been observed or thought about by a human as an aesthetic.

But what is an aesthetic. Francis Hutcheson amongst others describes it as a sense of order within complexity.

Step five. Any object real or imagined that has no utilitarian purpose that has been observed or thought about by a human as an aesthetic, which is a sense of order within complexity.

Postmodernism

It only becomes an artwork if the human responds to the object as a metaphor for social concerns.

Step six. Any object real or imagined that has no utilitarian purpose that has been observed or thought about by a human as a metaphor for social concerns.

But what are social concerns. Jean-Francois Lyotard wrote about the collapse of grand narratives leading to plurality and fragmentation.

Step seven. Any object real or imagined that has no utilitarian purpose that has been observed or thought about by a human as a metaphor for social concerns, which is about the collapse of grand narratives leading to plurality and fragmentation. -

What is a painting?There are also transcripts for each episode — GrahamJ

The problem is that Grayson Perry does not seem to give his opinion as to what art is, other than saying what art could be.

https://downloads.bbc.co.uk/radio4/transcripts/lecture-1-transcript.pdfNow there’s no easy answer for this one, I’m sorry to say. I’m not going to live up to sort of like the Reith Lecturers’ code of honour which is to have definite strong opinions and be a kind of certainty freak because many of the methods of judging are of course very problematic and many of the criteria that you use to assess art are conflicting. I mean we have financial value, popularity, art historical significance, or aesthetic sophistication. You know all these things could be at odds with each other. -

What is a painting?I was beginning to wonder if part of what makes paintings and drawings paintings or drawings is that they are in 2-dimensional space. — Moliere

The question why is a painting not a sculpture is the same kind of question as asking why is a play not a film or why is a cat not a dog.

If something is a domesticated mammal and a subspecies of the gray wolf then it it is a dog and if something is a small, domesticated carnivorous mammal that is commonly kept as a pet then it is a cat.

If something is performed by live actors then it is a play and if something is a recording of live actors then it is a film.

If something is an artwork in 2D then it is a painting and if something is an artwork in 3D then it is a sculpture.

There is a human need to divide the observed world into smaller parts using language. This helps the human make better sense of their observed world. As Derrida pointed out, part of the meaning of a word derives from what it is not.

===============================================================================

but even the painter wouldn't say it's art — Moliere

The man paints a wall red. How do you know what is in his mind?

===============================================================================

On the multiplicity of artworlds — Moliere

As of 1 January 2025, there were about 8,250,423,613 different artworlds, in that it seems true that no two people have identical minds. As they say, the world exists in the head.

===============================================================================

Also, a general caution for family resemblance -- I like that concept a lot for tamping down the desire for universal and necessary conditions as a foolhardy quest.........................................There's still the work of specifying that family resemblance — Moliere

Yes, even if we agree that there is a family resemblance between André Derain's "Henri Matisse" (1905) and Georges Braque's "The Harbour" 1906, this doesn't explain why there is a family resemblance.

As a first step, the "why" can be put into words. The Tate writes:

Fauvism is the name applied to the work produced by a group of artists (which included Henri Matisse and André Derain) from around 1905 to 1910, which is characterised by strong colours and fierce brushwork. The paintings Derain and Matisse exhibited were the result of a summer spent working together in Collioure in the South of France and were made using bold, non-naturalistic colours (often applied directly from the tube), and wild loose dabs of paint. The forms of the subjects were also simplified making their work appear quite abstract.

There is much that can be said.

But sooner or later, some words cannot be described using other words, such as "Wild loose dabs" or "fierce brushwork". The meaning of words such as "wild" and "fierce" cannot be said but can only be shown.

And they can only be shown as family resemblances.

It is the intrinsic nature of the brain to be able to discover family resemblances in what it is shown, and this ability is beyond any philosophical explanation -

What is a painting?I am sure a case could be made that I am not looking at things properly. And a case could be made that there is no such thing as looking at these things properly. And a case could be made that I was looking at things properly, (no matter what I said I saw, or because of what I said I saw, namely, a sculpture with a blue wall). — Fire Ologist

On the other hand, perhaps artworks need to looked at "properly" if they are to make sense.

Today, as a simplification, we can say that there are two main approaches to painting, Modern and Postmodern. The Modern is drawing attention to the aesthetic within the modern world, such as Georges Braque, and the Postmodern is drawing attention to the social situation within a postmodern world, such as Damien Hurst.

These are two very different approaches to the artwork.

Problems arise if Modern artworks are looked at from the perspective of a Postmodernist viewpoint, or Postmodern artworks are looked at from the perspective of a Modernist viewpoint.

In this sense, looking at an artwork "properly" means looking at an artwork as it was intended by the artist. If intended by the artist as a Modernist artwork it should be looked at within the domain of Modernism, and if intended by the artist as a Postmodernist artwork it should be looked at within the domain of Postmodernism. -

What is a painting?Is that maybe a sculpture about a painting? Since it incorporates the room space to complete its portrayal? — Fire Ologist

As you are seeing it on your screen, the artwork could be a photograph, which just happens to be of a blue wall. -

What is a painting?Pieter Vermeersch’s (Kortrijk, 1973) artistic research of painting expands beyond the confinement of the canvas.

https://www.perrotin.com/artists/Pieter_Vermeersch/142#biography

-

What is a painting?But for now I'm trying to develop the ideas of aesthetic thinking, with respect to philosophy at least, at all. — Moliere

A simple division is to split paintings into the Modern, artists such as Derain, and the Postmodern, artists such as Cindy Sherman.

Typically, Modern art specifically includes the visual aesthetic and Postmodern art specifically excludes the visual aesthetic.

The philosopher Francis Hutcheson wrote about aesthetics and beauty. For Hutcheson, beauty is not in the object but is in how the object is perceived, and stems from uniformity amidst variety. Diverse elements come together in a way that feels balanced and harmonious, a dynamic process where we sense order within complexity.

If beauty is the sense of order within complexity, this can apply to more than paintings and can apply to any thought about the world, including philosophical thought.

The OP asks "What makes a painting a painting?"

When you say "aesthetic thinking", do you mean either i) philosophical thoughts that may not be aesthetic about aesthetic objects or ii) philosophical thoughts that are aesthetic about objects that may not be aesthetic? -

What is a painting?I'm enjoying these various distinctions between drawings, paintings, pictures, and art: wet/dry, High/low, warm-up/real-deal... — Moliere

As the French say "vive la différence", or rather, as Derrida might have said, "vive le différance".

In what way is something that is a painting different to something that is not a painting?

According to Derrida, meaning is not inherent in a sign, but arises from its relationship with other signs, and where the meaning of a sign changes over time as new signs keep appearing and old signs disappear (Wikipedia - Différance)

For example, the word "house" derives its meaning from the way it differs from "shed", "mansion", "hotel", "building" etc.

For example, Derain's painting "Houses of Parliament" derives its meaning from the way it differs to the building the Houses of Parliament.

It is as much about language as it is about the language of art.

Symbols are only useful if they have an opposite. Good only means something if there is bad. Hot only means something if there is cold. Painting only means something if there are things that are not paintings, such as sculptures, photographs, music or happenings.

So what is a painting may be answered by saying that a painting is not a sculpture, not a photograph, not music and not a happening. -

What is a painting?Don't you think this may be considered a painting as well? — javi2541997

Certainly. In the same way that Braque's "Le Figaro" includes text within its composition.

They are both paintings because they are both intended as paintings, and not intended as something like a street sign giving directions to drivers.

The same object can be an artwork and not an artwork at the same time.

For example, if the stop sign is intended as a street sign giving directions to drivers then it is not an artwork, but the moment someone says "that stop sign looks like an artwork" then it becomes an artwork.

As the saying goes "beauty is in the eye of the beholder".

-

What is a painting?Paintings at one point in history a kind of primitive 'Photograph,' but now I think the photograph is more 'primitive' in what it can achieve. — I like sushi

A photograph is a copy of what exists in the world, and therefore depicts what is necessarily true.

A painting is a copy of what could exist in the world, and therefore depicts what is possibly true.

Primitivism is a style of art used by artists in an industrial society that duplicates the style of art used by artists in pre-industrial societies.

Photography as an invention of an industrialised society can only copy the world as it exists in an industrialised society, and therefore cannot depict the primitivism of a pre-industrial society.

Only painting can copy what the world could have been like in a pre-industrial society, and therefore can depict the primitivism of a pre-industrial society. For example, Picasso's "Portrait of Max Jacob". -

What is a painting?What is a painting — Moliere

The meaning of "a painting" cannot be put into words, either as a definition or a description. The meaning of "a painting" cannot be said but can only be shown.

The meaning of "a painting" may be understood by looking at the objects that have been named in the following set: {Monet's "Landscape with Factories", Derain's "Houses of Parliament", Klimt "Pine Forest", Leonardo da Vinci "Lady with an Ermine", Giotto "The Betrayal", El Greco "View of Toledo", Albert Bierstadt "The Rocky Mountains", Jolomo "The Light of Argyll"}

Because the elements of the set share family resemblances, Russell's Paradox, resulting from unrestricted comprehension, may be avoided.

As Wittgenstein pointed out, the observer who looks at the objects named in this set will discover a family resemblance between these objects, and this family resemblance will be "a painting".

In order to understand the meaning of "a painting", the set does not need to include every painting ever painted, but only a sample.

As there is no "correct" meaning to any word or expression, there is no "correct" meaning to the expression "a painting". Person A looking at this set will discover a family resemblance that will be different to person B looking at the same set. Person A looking at a set 8 elements will discover a different family resemblance to a set that contains 16 elements. But even, so there will be a family resemblance between different family resemblances.

In answer to the question, what is a painting, a preliminary meaning of "a painting" may be understood by looking at the following 8 objects.

-

A Matter of TasteRight, but research indicates that visible features of an organism tend to be sexually selected. So it wouldn't be about patterns in chaos, it would be about sex. — frank

It doesn't seem random that animals are often aesthetically pleasing. Evolution seems to favour aesthetic solutions.

There appears to be a direct analogy between Frances Hutcheson's explanation of aesthetics as "uniformity amidst variety" and life's dependence on an ability to discover patterns in chaos.

It would follow that if life is fundamentally aesthetic, and if philosophy is trying to understand life, then aesthetics in philosophy must be a "thing".

-

A Matter of TasteSo I guess that is what you mean? "Great artist" = "someone I like a lot". — J

Both Derain and Banksy are artists. But are they equally great?

If greatness is determined by monetary value, they are probably equally great as a Banksy original more than likely sells for as much as a Derain original.

If greatness is determined by popularity amongst the public, then Banksy is probably greater than Derain.

If greatness is determined by the humour in their works, then Banksy is clearly greater than Derain.

If greatness is determined by an aesthetic of form and shape, what Frances Hutcheson called "uniformity amidst variety", then Derain is clearly greater than Banksy.

You are right that my equating greatness as an artist with an aesthetic of form and shape is personal to me. Others may well equate greatness as an artist with monetary value, popularity or being humorous.

RussellA

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum