-

Is there an external material world ?No visible colour is presented in experience. — Isaac

Of course it is. Some people see the dress as black and blue, others as white and gold.

I honestly can’t be bothered to rehash the old arguments where you try to deny this very basic, empirical fact. -

Is there an external material world ?People do, yes. 'Red' is not the term we use to describe the hidden state that causes birds to see what we would call red (if we had the same ocular equipment). It's the name we give to the hidden state which causes most humans in normal light conditions to respond in a predictable manner. If a bird learned human speech and called those eggs 'red' he'd be wrong. — Isaac

Hidden states are only half the picture. There’s also the non-hidden states, e.g the visible colour that is presented in experience and which, according to you, people can “get wrong”.

Direct and indirect realists want to know if we can trust these non-hidden states to show us the nature of the mind-independent world. Direct realists say that we can because these non-hidden states are the mind-independent nature, whereas indirect realists say that we can’t because these non-hidden states are only representative of and/or causally covariant with the mind-independent nature. -

Is there an external material world ?Yes. Why wouldn't I be? — Isaac

Because you said before that people can see the wrong colours. -

Is there an external material world ?Why must the hidden state be either cream-coloured, or red-coloured, why can it not be both? — Isaac

If there’s just one possible case where it isn’t both then the point stands.

So you would have to argue that mind-independent objects are every colour that any possible organism could possibly see them to be. Are you willing to commit to that? -

The nominalism of Jody AzzouniDoesn't special relativity depend on relations with it's observer-based frame of reference? How would you reformulate either special or general without relations? — Marchesk

Quantum mechanics is incompatible with relativity and so assuming a quantum theory of gravity can be found then he need not worry about relativity.

We carve this variance into objects, properties and relations, because of our biology and culture.

…

So while Azzouni is a hard-core nominalist, he rejects anti-realism and logical positivism. — Marchesk

If he says that we carve this variance into objects then it seems that he’s being an anti-realist about these objects, even if he’s not being an anti-realist about the “fabric with features”.

My major problem with Humean causality is that it gives no explanation for why A always follows B, which could change at any point in the future. — Marchesk

What does it mean for A to cause B? Does it mean that B happens because A happens? And does this mean that if A didn’t happen then B would not have happened? And does this mean that there is no possible world where A does not happen and B happens? Even this account is explained in terms of a sequence of events. Or is there an account of causation that provides more “substance” to the relation between A and B? -

PhenomenalismI’m not sure that is the case. We directly perceive apples through light. — NOS4A2

Now you're changing what you mean by perception being direct. First you said that perception being direct means that "there is no mediating factor between experienced and experiencer" and yet in the case of seeing an apple the air, the light, and glasses or contact lenses are a mediating factor between what is experienced (the apple) and the experiencer.

What do you mean now? Just throwing in the word "direct" but admitting of a mediator is no answer at all. You might as well say that we directly perceive things that happened in the past and in another location through a CCTV recording. Saying that such a perception here is "direct" just makes the word "direct" meaningless and doesn't address the metaphysical question of perception at all. -

PhenomenalismAir, light, glasses, and contact lenses aren't made up mediums. — Michael

Exactly. — NOS4A2

Then you admit that our visual perception of an apple is mediated by air, light, and sometimes glasses or contact lenses. Therefore, by your own account, we don't directly see apples.

You experience the image your way, I experience it my way. — NOS4A2

Yes, which is to say that our sensory systems elicit different sense-data.

There is no need to evoke “sense-data” or some other medium to explain it when there are actual things that can account for these differences. — NOS4A2

Given that the hard problem of consciousness hasn't been solved, clearly this is false. -

PhenomenalismYou’re confusing a actual medium in the world with the mediums made up by indirect realists. — NOS4A2

Air, light, glasses, and contact lenses aren't made up mediums.

It only proves that we see it differently, not that something called sense-data is an emergent phenomenon from the brain. — NOS4A2

And what does it mean to "see something differently"? It means that we experience different sense-data. I experience white and gold, you experience black and blue. The colours we experience are the medium by which we indirectly see the photo of a dress. -

PhenomenalismIn terms of direct realism, yes. — NOS4A2

But there's a number of mediums between the apple and the sense receptors in our eyes (air, light, sometimes glasses or contact lenses), so by your own account it isn't direct. You now seem to mean something else by "direct". What is it?

Does it have a physical structure or chemical make-up? Can we put some of it under a microscope? — NOS4A2

We don't know yet, the hard problem of consciousness hasn't been solved. Regardless, there is something which is sense-data, whether physical or not, as proved by the fact that you and I can look at the same photo of a dress and yet see different colours. These colours are sense-data.

And, again, you seeing someone pick up and eat an apple isn't evidence that such sense-data doesn't exist and so isn't evidence against indirect realism. -

PhenomenalismOf course I’m not speaking of sight only. But you keep limiting it to sight. Nonetheless, we see everything in our periphery, including light, air, glasses, etc. directly. — NOS4A2

But do we see the apple directly?

Point to me the sense-data. No sense-data appears between observer and observed. Sense-data is irrelevant if it cannot be shown to exist. — NOS4A2

Sense data is an emergent phenomenon, brought about by brain activity. If you're asking me to point to something that is physically situated between the apple and someone's eyes then your request is misguided. -

PhenomenalismAgain, viewing things in the world such as air, glasses, light, and so on is direct realism. — NOS4A2

The air, light, glasses, and contact lenses are the medium between the apple and one's eyes. Hence why, according to your account, seeing an apple isn't direct.

Sense-data is another such medium. — NOS4A2

You can't dismiss the medium of sense data by saying that you can see someone pick up and and eat an apple. As I have repeatedly said, your claim here is irrelevant to the discussion. -

PhenomenalismNo medium appears at any point in the scenario. The evidence for a medium is zero. — NOS4A2

There's air, light, and in some cases glasses or contact lenses.

But this just shows that you have a fundamental misunderstanding of direct and indirect realism. Indirect realism claims that the "medium" is the sense-data that occurs "in the head". You and I look at the same photo of a dress and yet you see a black and blue dress and I see a white and gold dress. We have different sense-data, and this sense-data is the immediate object of perception.

You may disagree with this claim, but saying that you can see someone pick up and eat an apple says nothing that addresses it. It's a non sequitur. -

Is there an external material world ?The problem with 'direct' and 'indirect', which we're seeing here, is that both require a network model (a model of the nodes so that we could say "these two are right next to one another" (direct), and "these two are separated by intervening nodes"(indirect). But the intervening nodes must, by definition, be indirectly experienced (if they were directly experienced, they would not be intervening nodes). — Isaac

I think that this interpretation places too much focus on the word used to label the metaphysics and not enough on the problem that the metaphysics is trying to solve.

The epistemological problem of perception is: do our ordinary experiences provide us with information about the existence and nature of the external world. Direct realists say that they do "because experience is direct" and indirect realists say that they don't "because experience is indirect".

Rather than quibble over the meaning of "direct" and "indirect" it is best to simply address the underlying problem. If it can be shown that ordinary experiences do not provide us with information about the existence and nature of the external world then experience isn't direct, whatever "direct" is supposed to mean. And I think that this is where the character of the experience is what needs to be considered, and whether or not it makes sense to think of this character as being the character of mind-independent objects.

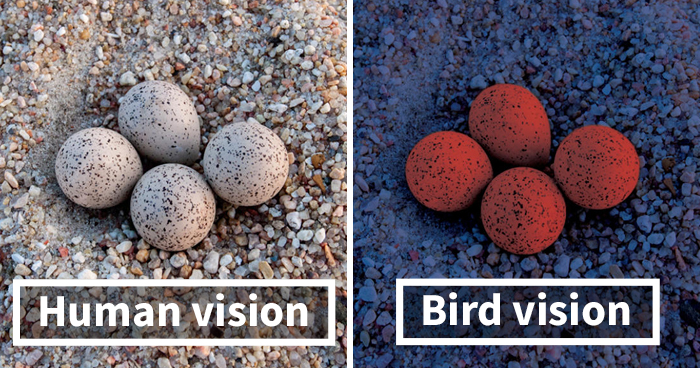

So let's refer back to an image I posted before:

The character of a human's experience is different to the character of a bird's experience. This claim is true whether you want to make sense of this in terms of qualia/sense-data or in terms of Bayesian models, or in terms of something else. If direct realism is true then the mind-independent world is of the same character as one of these experiences. The eggs have the colour either we or the birds see them to have even when not being seen; they're either cream-coloured or they're red-coloured (or we're both wrong and they're some other colour).

This is where we run into the first problem: given that the character of the bird's experience differs from the character of the human's experience, one (or both) of these are "wrong" (in the sense that the mind-independent world isn't of the same character as one (or both) of these experiences). As such, at least one of the experiences isn't direct. The Common Kind Claim then comes into effect; there is no fundamental difference between the nature of a veridical and a non-veridical experience, just as there is no fundamental difference between the nature of a true statement and a false statement. The veracity of the experience (or statement) is determined not by the nature of the experience but by whether or not the facts "correspond" with the experience; the veracity of the experience is independent of the experience.

The second problem is that our best descriptions of the mind-independent nature of the world (things like the Standard Model) do not find that things have visual colours. It finds that they absorb photons of certain wavelengths and emit or reflect photons of other wavelengths, but that's a very different thing to the cream- or red-colour as given in experience and shown in the photo above, hence why different organisms see different colours when stimulated by the same kind of light.

We then seem to have an answer to the epistemological problem of perception: our ordinary experiences do not provide us with information about the existence and nature of the external world. We don't need to get lost in an effectively pointless debate over the words "direct" and "indirect". -

Is there an external material world ?Can we think without language?

Imagine a woman – let’s call her Sue. One day Sue gets a stroke that destroys large areas of brain tissue within her left hemisphere. As a result, she develops a condition known as global aphasia, meaning she can no longer produce or understand phrases and sentences. The question is: to what extent are Sue’s thinking abilities preserved?

Many writers and philosophers have drawn a strong connection between language and thought. Oscar Wilde called language “the parent, and not the child, of thought.” Ludwig Wittgenstein claimed that “the limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” And Bertrand Russell stated that the role of language is “to make possible thoughts which could not exist without it.” Given this view, Sue should have irreparable damage to her cognitive abilities when she loses access to language. Do neuroscientists agree? Not quite.

This language system seems to be distinct from regions that are linked to our ability to plan, remember, reminisce on past and future, reason in social situations, experience empathy, make moral decisions, and construct one’s self-image. Thus, vast portions of our everyday cognitive experiences appear to be unrelated to language per se.

But what about Sue? Can she really think the way we do?

While we cannot directly measure what it’s like to think like a neurotypical adult, we can probe Sue’s cognitive abilities by asking her to perform a variety of different tasks. Turns out, patients with global aphasia can solve arithmetic problems, reason about intentions of others, and engage in complex causal reasoning tasks. They can tell whether a drawing depicts a real-life event and laugh when in doesn’t. Some of them play chess in their spare time. Some even engage in creative tasks – a composer Vissarion Shebalin continued to write music even after a stroke that left him severely aphasic.

Some readers might find these results surprising, given that their own thoughts seem to be tied to language so closely. If you find yourself in that category, I have a surprise for you – research has established that not everybody has inner speech experiences. A bilingual friend of mine sometimes gets asked if she thinks in English or Polish, but she doesn’t quite get the question (“how can you think in a language?”). Another friend of mine claims that he “thinks in landscapes,” a sentiment that conveys the pictorial nature of some people’s thoughts. Therefore, even inner speech does not appear to be necessary for thought.

Have we solved the mystery then? Can we claim that language and thought are completely independent and Bertrand Russell was wrong? Only to some extent. We have shown that damage to the language system within an adult human brain leaves most other cognitive functions intact. However, when it comes to the language-thought link across the entire lifespan, the picture is far less clear. While available evidence is scarce, it does indicate that some of the cognitive functions discussed above are, at least to some extent, acquired through language.

Perhaps the clearest case is numbers. There are certain tribes around the world whose languages do not have number words – some might only have words for one through five (Munduruku), and some won’t even have those (Pirahã). Speakers of Pirahã have been shown to make mistakes on one-to-one matching tasks (“get as many sticks as there are balls”), suggesting that language plays an important role in bootstrapping exact number manipulations.

Another way to examine the influence of language on cognition over time is by studying cases when language access is delayed. Deaf children born into hearing families often do not get exposure to sign languages for the first few months or even years of life; such language deprivation has been shown to impair their ability to engage in social interactions and reason about the intentions of others. Thus, while the language system may not be directly involved in the process of thinking, it is crucial for acquiring enough information to properly set up various cognitive domains.

Even after her stroke, our patient Sue will have access to a wide range of cognitive abilities. She will be able to think by drawing on neural systems underlying many non-linguistic skills, such as numerical cognition, planning, and social reasoning. It is worth bearing in mind, however, that at least some of those systems might have relied on language back when Sue was a child. While the static view of the human mind suggests that language and thought are largely disconnected, the dynamic view hints at a rich nature of language-thought interactions across development. -

Phenomenalism“Direct” in the sense that we directly perceive the environment, including the lights, smells, touch, taste, of apples. “Indirect” in the sense that we perceive the environment through some kind of medium. — NOS4A2

Then explain to me how someone else picking up and eating an apple shows that no medium is involved when they see an apple. -

PhenomenalismThere is no mediating factor between experienced and experiencer, so the experience is not indirect. — NOS4A2

What do you mean by this? If you’re saying that apples directly stimulate our sense receptors then except in the case of touch this is false; apples don’t directly stimulate the rods and cones in our eyes, so visual perception under your account isn’t direct.

Or do you mean something else? -

PhenomenalismWe either directly perceive the world or we do not. — NOS4A2

And seeing that someone’s hands are in contact with an apple isn’t evidence that we directly perceive the world. It isn’t evidence for Direct Realist Presentation as is defined in the article. -

PhenomenalismBut I can watch you directly eat an apple. — NOS4A2

And as I said before, direct bodily interaction isn’t direct phenomenological experience. So again, read the SEP article so that you can actually understood what direct (and indirect) realism is actually saying.

At the moment you’re just misappropriating the phrase “direct perception” to mean something completely different, and arguably irrelevant. -

PhenomenalismYou’re assuming that the apple is being presented in something called experience. But there is no evidence of such a place, let alone that apples appear in them. — NOS4A2

Then there’s no evidence for direct realism, because as the SEP article says, and as you yourself referenced, direct realism is the position that ordinary, mind-independent objects are directly presented in experience. -

PhenomenalismYou’re assuming that the apple is being presented in something called experience. But there is no evidence of such a place, let alone that apples appear in them. — NOS4A2

I know from experience that I have phenomenological experiences. I can’t speak for you; perhaps you’re a p-zombie. Which again shows why me seeing someone else eat an apple isn’t evidence that they have a direct realist experience. -

PhenomenalismYou’re watching him eat an apple. That’s not the same thing as watching an apple being directly presented in his visual or auditory or olfactory or tactile or taste experience.

-

PhenomenalismThere are other senses, though. — NOS4A2

Picking up and eating an apple isn’t evidence of a direct auditory experience, or a direct olfactory experience, or a direct taste experience, or a direct tactile experience, etc. -

PhenomenalismHe's blind. He cannot see the apple. — NOS4A2

Then picking up and eating an apple isn’t evidence that someone has a direct visual experience of an apple. -

PhenomenalismFrom this view, to watch a blind man directly eat an apple on the one hand and say he is not experiencing the apple directly on the other is absurd. — NOS4A2

Does the blind man have a direct visual perception of the apple? -

PhenomenalismIt shows that he is directly interacting with an apple. — NOS4A2

The contact between him and the apple is direct, therefor the experience is direct. — NOS4A2

Bodily interaction is not phenomenological experience. The former being direct says nothing about the latter being direct. A blind man can pick up and eat an apple, therefore picking up and eating an apple is not evidence that someone has a direct visual perception of the apple.

If a schizophrenic says he is hearing voices, yet others do not, we can confirm that he is in fact not hearing voices — NOS4A2

This is just playing a word game. He has the phenomenological experience of hearing voices, the same as someone having a veridical experience. The difference between the two concerns the nature of the cause.

Given the Common Kind Claim that the phenomenological experience of an hallucination is of the same kind as the phenomenological experience of a veridical experience, and given that mind-independent objects are not directly present in an hallucination, it follows that mind-independent objects are not directly present in a veridical experience.

A causal connection does not entail direct presentation. Even the direct realist should accept this, given the everyday cases of CCTV cameras and mirrors. -

PhenomenalismI don’t understand what you’re saying. The boxes are either empty or have something in it. That’s just the premise of his thought experiment.

-

PhenomenalismOkay, then it’s still the case that each person’s box is either empty or has one or more things in it, and that the thing(s) in one person’s box might be different to the thing(s) in another person’s box.

-

PhenomenalismWittgenstein says the following "Suppose everyone had a box with something in it: we call it a "beetle". No one can look into anyone else box, and everyone says he knows what a beetle is only by looking at his beetle. Here it would be quite possible for everyone to have something different in his box. One might even imagine such a thing constantly changing. But suppose the word "beetle" had a use in these people's language? If so it would not be used as the name of a thing. The thing is the box has no place in the language-game at all; not even as a something: for the box might even be empty. No, one can 'divide through' by the thing in the box; it cancels out, whatever it is. That is to say: if we construe the grammar of the expression of sensation on the model of 'object and designation' the object drops out of consideration as irrelevant." — Richard B

There’s still something inside each person’s box. I don’t understand the point you’re trying to make. -

PhenomenalismAnd seeing someone pick up and eat an apple shows nothing that supports Direct Realist Presentation.

-

PhenomenalismActive inference or Bayesing qualia? — Isaac

The latter. The former doesn’t address the hard problem of consciousness and makes no ontological commitments as one of the papers I referenced explicitly says. -

PhenomenalismBut he’s touching it, destroying it, consuming it. At no point are the interactions indirect, so we need not say the experience is indirect. — NOS4A2

Read up on the arguments presented in the SEP article. Nothing you’re saying here has any relevance to what is meant by direct or indirect realism. -

PhenomenalismSo why the indirect realist prefers the limited and impoverished view of his own biology is the real question. — NOS4A2

Because they prefer the certainty of appearances and/or immediate sense data of their private world. — Richard B

It’s not about what people prefer but about what they find the evidence and reasoning shows. -

PhenomenalismCan't say fairer than that. What is unpersuasive is unpersuasive. — Isaac

Or perhaps I should say, given that I don’t know much about cognitive science, I can’t understand the attempt to “Bayes” qualia.

So the best I can do is withhold judgement until it becomes accepted by the wider scientific community. And from what I understand it’s just Clark’s/Friston’s/Wilkinson’s theory and not something that has been scientifically demonstrated? -

PhenomenalismYou're still modeling hidden states, the subject of your inferences. — Isaac

According to you I don’t know enough about cognitive science to address this comment so I won’t bother. We’ve already gone through it enough in the other thread anyway. Suffice it to say, I don’t find the attempt to “Bayes” qualia at all convincing. -

PhenomenalismIt's whatever inputs you used (probes, computers, whatever). The brain has modeled them as a cat. It's not a very good model. When it tries to interact with the cat it may find that out.

If, however, it lived in a society of other BIVs who all refer to the same hidden state (judged by joint interaction) as 'cat' then that's clearly what the word means in that language community. — Isaac

I don’t find this interpretation at all reasonable. I think a far more reasonable interpretation is to accept that the brain doesn’t see the vat that it is contained in, or whatever mechanical devices control its sight.

You may have missed my edit, so to reiterate: after taking LSD I don’t then see that LSD when seeing the things it causes me to see. Even a direct realist can accept that. They’ll say that the LSD is in my stomach and bloodstream and that I can’t see through my skin to see it. -

PhenomenalismThe counterargument is that the thing you see is what causes you to see what you see. — Isaac

So if I put a brain in a vat and configure it to cause the brain to see a cat then the cat that the brain sees is the vat (or me)? Seems to me that it would be more accurate to say that the brain doesn’t see the vat (or me).

Or for a more realistic example, when I see crazy shit after taking LSD I’m seeing the LSD? -

PhenomenalismI don't understand. Answering your second proposition there would seem to entail a truth claim. — Isaac

I don’t believe that truth consists in a proposition’s correspondence to some mind-independent state of affairs, and so I don’t believe that an apple being red requires an apple being red to be a mind-independent state of affairs.

You seem to be simply assuming that if you see the apple indirectly you must not 'really' be seeing the apple. — Isaac

I’m not. I’ve mentioned before that direct and indirect realists tend to talk past each other. The direct realist says something comparable to “we read about history” and the indirect realist says something comparable to “we read words”. Both are true. But in terms of the metaphysics, reading doesn’t provide us direct access to history, and perception doesn’t provide us direct access to their external cause. This by itself says nothing about “aboutness”.

Regarding my stronger phenomenalist/anti-realist claims, it’s not that we don’t “really” see an apple, it’s that an apple isn’t whatever mind-independent things causes me to see an apple. Something more than just a causal connection is required to say that the external thing is an apple. The vat or the computers that control it are not the apple that they cause the brain-in-a-vat to see. At the very least there needs to be some sort of resemblance between the thing I see and what causes me to see what I see. I think that this resemblance fails in the case of so-called secondary qualities like colour, and even, contrary to perhaps many indirect realists, that this resemblance fails in the case of so-called primary qualities like shape. And so it is a mistake to say that an apple is whatever causes us to see an apple. The apple that I see and the mind-independent wave-particles that are responsible for me seeing an apple are two very different things. -

PhenomenalismI was talking about both being true. As I've mentioned before, it is true that the stars in Orion are in the shape of a man with a bow. It is also true that they are in the shape of a rainbow.

Reality can be exactly as the standard model describes, and as we ordinarily perceive it. Nothing I perceive is in contradiction with the standard model. — Isaac

I agree, but this discussion isn’t about truth, it’s about whether or not the things we see are mind-independent. I see an apple, the apple is red, I eat the apple, the apple nourishes me, etc. All of this is true but none of this is some mind-independent state-of-affairs that is directly perceived.

Michael

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2025 The Philosophy Forum