-

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / Phenomenalism

BTW, I'm reading this right now:

It has a similar set of ideas at its core, although it goes a lot further, trying to show how the "enlightened," view of reality ties into conceptions of human freedom, the pursuit of the sciences, art, ethics, and ultimately, conceptions of God.

It isn't perfect, but a very neat book. It draws on Whitehead, Wittgenstein, and Murdoch the most in terms of modern philosophers, along with Aristotle, Saint Augustine and Kant. Although the big sources of inspiration are in the title.

It's sort of neat to see the tie ins between Wittgenstein and Hegel, given how Russell was such a reaction against Hegel, and influenced

Wittgenstein.

Of course, how is simply recognizing the nature of being "mystical?" It's a loaded term for sure. But I'd say it fits in that we obviously have such a strong tendency NOT to see the world this way, making the turn a sort of "revaluation." -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

Tehran might want a conflict to distract from their domestic woes, but Russia? This seems like nothing but risk for Russia.

What happens if Tehran decides to support Gaza by having Hezbollah or its forces in Syria attack Israel? One obvious way to punish Iran would be to offer more air support to Syria's various rebels, something the IDF has tacitly done to some degree. That could be enough to throw off the stalemate and throw the SAA back on the back foot.

And what does Moscow do then? Deploy scarce air defenses to Syria to inflict higher costs on Israel? But they already don't have enough in Ukraine and when Ukraine gets the F-16 they will be facing a much increased sortie rate. Plus, if the air defenses are destroyed, do they admit defeat at the hands of a nation with a population the size of a large city or do they have to double down?

Already, Armenia is demonstrating that security assurances from Russia don't mean a whole lot right now. A shift in Syria would be an even larger blow.

Plus, weapons Iran sends against Israel can't go to Ukraine. I'd imagine the Russians are actually pressuring Tehran not to attack from Syria quite a bit. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

My belief is that the Israelis want peace and their enemies do not.

This was perhaps true in the 1990s and very early 2000s, and maybe has some truth to it in the median preferences of "people on the street," but those weilding political power in Israel absolutely do not seem to care about peace. I'd say the ruling coalition is quite similar in Hamas in that the war has become more about bludgeoning domestic opposition and building up patriotic support for the ruling government to paper over corruption and failure to deliver on domestic goals.

Both sides have become intransigent and unable to bargain in good faith.

That's not why I think it's delusional and nihilistic though. It's delusional because its believes in some great millenarian struggle that solves the problems. But it's completely unclear how even destroying Israel's military and genociding its people would fix the problem (not to mention the problem posed by their large nuclear arsenal).

What happens next then? Syrians aren't under Israeli rule, and yet when they came out to protest they were met with belt fed machine guns firing into crowds. Cities in revolt were shelled into dust. Egypt has been more stable, but the last time large scale popular protest occured, after the government was deposed by the military, you also had security forces firing indiscriminately into crowds. Abductions, disappearances, and torture continue.

It's nihilistic in the sense ISIS is. Sure, Assad absolutely deserves to be violently resisted, but the ISIS success plan was fairly fantastical and they kept doing things (e.g. all the gorey videos) that obviously hurt their odds of winning, and of setting up a functional peace even if they did win.

There does come the question of: "the men parading naked women through the street in jubilation and who have made their peace with shooting young children, what sort of state do they lead and how do they deal with internal dissent and minorities?"

You see this sort of result in the Taliban now facing multiple renewed insurgencies within Afghanistan. They have the same two fold problem of the career criminal element having been empowered and the true radicals continuing a sort of "eternal war," within the state. But the Taliban, for all its many flaws, is a good deal more pragmatic and visionary than Hamas. They might have an ugly vision of "what comes next," but they had a vision.

I say "nihilistic," because there isn't this focus on "what comes next." How you win a war matters as much as thatyou win it, sometimes more (recall, the Soviets "won" the Winter War). The retreat from any sort of coherent strategy into "the apocalyptic struggle will come upon us, many, maybe most will die, and destiny will carry us through," is nihilistic in that it doesn't seem to ask what comes next or particularly to align to a big picture strategy.

Maybe it's there and hidden? This is one of the problems with running your war in a way that is very opaque, even to your own populace. And Israel has forced this opacity on them to their own detriment.

And this is where I think you see the short term successes of Israel's assassination campaign truly backfiring. They have certainly been successful in destroying Hamas' leadership, but that's resulted in two groups coming to the fore. Died in the wool radicals set on total, explicitly genocidal victory, and your mafioso types. It's a conundrum. On the one hand, more quality leadership could do a lot more to organize resistance, but on the other, quality leadership gives you someone to bargain with who can actually control their own side and has a vision for the future.

But then, Israeli politics have done this same thing to their side, so...

Edit: BTW, it's not just the violence that makes me say this. The PVA did some pretty atrocious things in Vietnam, much larger massacres at times. But the larger actions of Giap an Ho always had a clear focus. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

It feels as if, had they not done something like this, they would simply remained ignored as Israel gets peace treaty after peace treaty with traditional enemies. It's no justification mind you, it's context.

I don't think Israel getting recognition and treaties with Arab states can be chalked up to Hamas "not carrying out enough attacks." Quite the opposite actually. Hamas, and the Palestinian cause more generally, lost support in the Gulf due to cozying up too much to Iran and doing things to support Iranian interests ("the enemy of my enemy is my friend," being what brought the Gulf states closer to Israel).

I'm sure both sides (Palestinians/Gulf Arabs) can find plenty to blame in the other for the breech, but Gulf support for the Palestinians didn't fall off because "they aren't doing enough to fight." Rather, the biggest cause was a conscious decision to pursue aid from Iran, which was more kinetic-focused, at the expense of aid from the Gulf, which was more political/ diplomatic/ economic. And I'd argue this preference in which type of aid to privilege seems to have more to do with "who rules over the Palestinian population in the occupied territories and how much power do they have over them," rather than "how does that leadership end the occupation?"

The problem goes beyond the relationship with the Gulf states. For example, Egypt blockades Gaza more stringently than Israel, with a lot of bad blood due to support for the insurgency in the Sinai. Not that the Palestinians didn't have good cause for violent resistance in Jordan, Lebanon, etc. They were treated horrendously outside Israel as well, used as pawns, forced into squalid camps, but from a real politick perspective it tended to erode their alliances (Jordan being the big exception to some degree).

So, while I think the Palestinians in general have plenty of reason for violent resistance, it's even more tragic that the resistance doesn't seem to actually be targeting any sort of realistic end goal. It often strikes me as cynical and nihilistic, aimed more at internal audiences. The gushing is bad because it's not only celebrating mass shootings, naked women being paraded through the streets as trophies, etc., but because it has this nihilistic and delusional vision where this will provoke Israel into the "final, apocalyptic, battle," they are fated to lose. It seems far more likely to simply decimate the Hamas leadership again and leave the Strip even more economically ruined before the status quo returns. By comparison, the rocket tit for tat strategy actually did seem to have some deterrent value and had clear aims re direct incursions into the OT.

I somehow doubt that Tehran expected anything of this scale, or Hamas for that matter. It's the sort of incursion that's been tried before and been far less successful. The likely expectation before the incursion would have been for some penetration but engagement by the IDF pretty rapidly, and at the border itself in many cases.

I'm not sure on the timing for the rockets, but if the volume came after the attack has proven shockingly effective, that would say something about the original intentions.

For opsec reasons I highly doubt anyone in Russia would have had an idea about this. Israel and Russia get along surprisingly well and Israel has historically had good humint inside Russia. It's also not necessarily a win for Russia. Israel is selling off a bunch of old Merkavas and they might be more willing to have such sales be part of some package for Ukraine now that Russian Kornets are showing up in Hamas' hand.

Iran and Russia is very much an alliance of convenience and there is plenty of bad history between the two. The Iran, Russia, NK arms alliance doesn't seem like something that will outlive any one parties near term local incentives. If Russia could get Iran to do anything they'd be trying to get them to contain the Azeris continuing to press on Armenia, since it's absolutely discrediting Russia as any sort of security guarantor and Iran has its own potent Azeri independence movement.

Russia wouldn't want it because they want all the weapons they can get out of Iran, who will be busy with this. Iran might want it as a distraction, but they have their own reasons to be reticent given they have at times seemed to be teetering towards civil war, shelling their own cities to deal with unrest. And they can rely on Russia much less as a check on Israel in Syria, making attacking from Lebanon or Syria in support of Gaza riskier. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

This just seems to be intentionally misunderstanding what people mean by "unprovoked." It's that the attack wasn't in response to an ongoing series of escalations, new border restrictions, a raid on the Al Aqsa Mosque, an assassination, etc., all the things that more commonly precede attacks. I don't think anyone supposes the situation came out of nowhere.

And that's important in what it says about Hamas' goals and reasons were in this case.

Thanks. Generally good points and I agree with a lot of it. Although it's a bit too gushing for my tastes. Running across the border and gunning down people while they wait for the bus or dumping your magazine into a night club crowd isn't exactly "blitzkrieg," or any of the other military superlatives mentioned. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

Yeah, and the justification for a more "mass shooting," less "military objectives" style of attack also rings pretty hollow vis-á-vis the Hamas leadership ordering this from their luxury penthouses in Qatar. They seem to have had an extremely businesslike attitude towards attacks over the last decade +.

I also don't think they expected to have killed this many people. It's a bit the dog that finally catches the car. There seems to have been a massive, systemic failure in the border defenses that had to occur to get to this point. So, a show of force probably expected to result in getting spotted and exchanging fire before breaking contact becomes hundreds of people getting shot in their beds.

By rights, this should be extremely damaging for Netanyahu for leaving the border garrisons under staffed and unprepared, but he'll probably use it to drum up support for himself. -

Joe Biden (+General Biden/Harris Administration)

I don't know if "being better than Trump," is necessarily the standard to aspire to. But yeah, the lack of a focus on developing young leaders is a problem and I would also argue that the reason mid to long term problems are so hard to tackle in the US, and in the developed world writ large, is partly because of gerontocracy. Climate change is likely to be far more of a problem in the second half of this century, a US debt crisis is probably a decade + away, etc. It's rather enraging to hear politicians dismiss issues that might come up as soon as 2040 as ridiculous to consider. If you're having a child today, they aren't going to get out of high school until 2041.

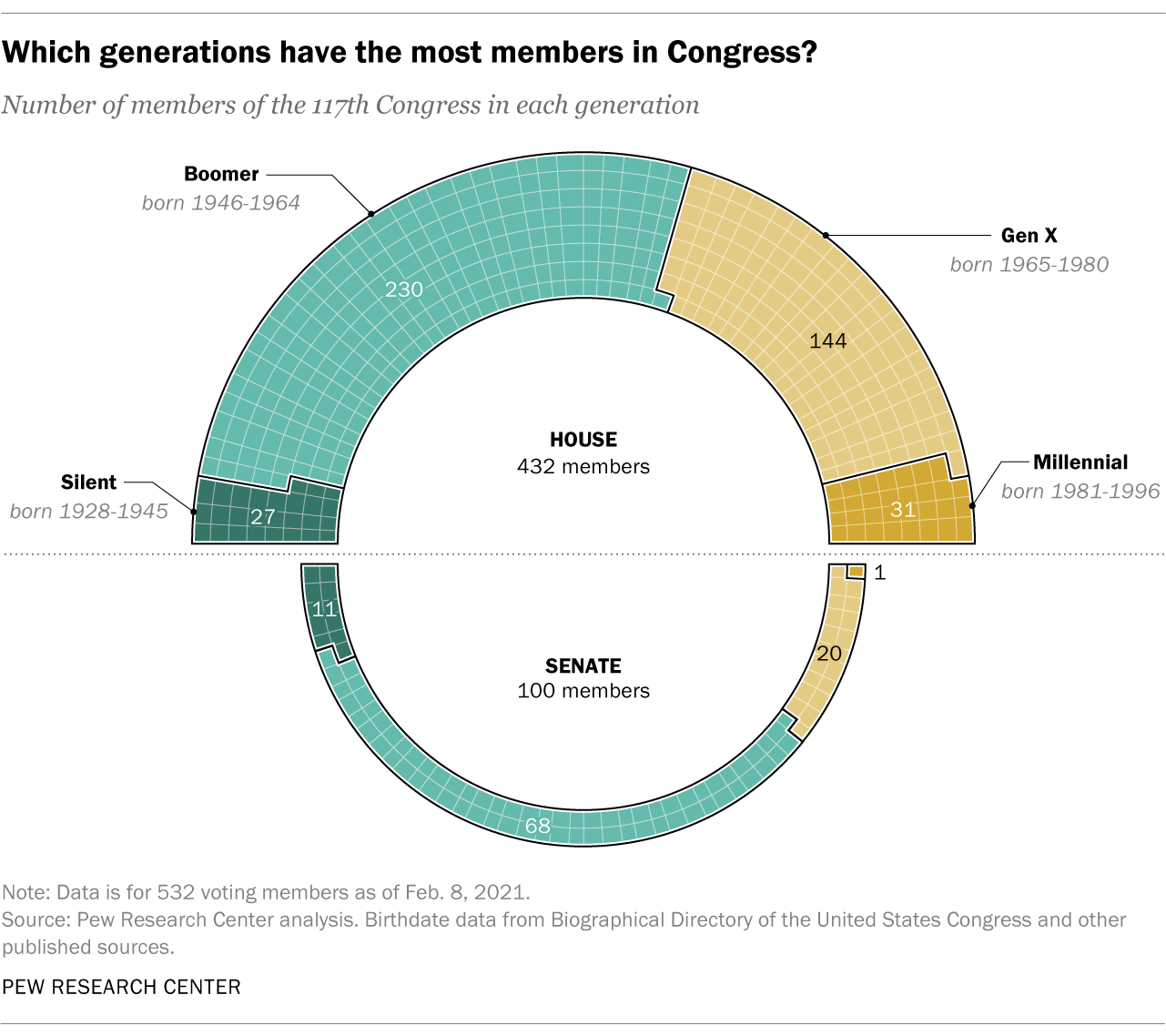

The population has grown older, but the representation is not at all in line with this growth. People under 45 are over a third of the adult population but represent 6% of legislators and a very small share of cabinet level positions too. And it's not like being in your mid-40's is young. It's middle aged. The Baby Boomers took over a majority in Congress and the White House at close to the same point in the "generation's" aging.

Unfortunately, across the West, the lopsided age-wealth gap also tracks very closely with ethnicity, so the two become tangled together in politics, forming a destructive witches' brew. "Why build schools, it's for those people," versus "why pay for pensions? Those are the racists who didn't want to pay for our schools."

And then on top of that you have the issue of the debt in the US, and funding the massively expensive entitlements for retirees (a problem everywhere), running smack dab into the time bomb issue of appropriate levels of inheritance taxation. This issue will become acute because wealth has come to skew very heavily towards older citizens, and inheritance will tend to keep that wealth very concentrated as it is passed on because Baby Boomer's had way less children on average, with most new growth coming from migration instead. Inheritance split between 8 kids does a good deal more to level it our, but 1 or 2...

Bit of a side rant, but I find the whole thing very dispiriting, but also fascinating. I think it could actually help ease ethnic tensions for people to realize that they are, in part, also just the time old tensions between the priorities of the old and the young that exist in any society, and that the trick is to try to find a fair compromise. -

Joe Biden (+General Biden/Harris Administration)

Parties can enforce discipline on rank and file members by threatening to withhold fund raising assets, donations, endorsements, committee assignments, etc., but once the person is famous enough and has their own funding resources and runs their own patronage network they are hard to contain.

Biden entered the 2020 race with enough name recognition and support from his association with Obama that he could be a spoiler, throwing the race to Bernie, and that seems to be what got him the nomination in the end. Parties have a much easier time punishing less well known candidates or legislators.

Plus, the Dems were gunshy about using party influence to corral the number of nominees after their near coronation of Clinton blew up in their faces.

Ultimately, the other candidates threw in with Biden to avoid what happened in 2016 to the GOP, a candidate the RNC absolutely did not want winning because there were too many other people fighting over the remaining votes (seems likely to happen again).

Truman and LBJ ultimately didn't run because they themselves thought it would hurt the party, not due to party discipline for example.

I don't have a particularly high opinion of Biden but his administration has been fine. But because of his history, I feel like this has more to do with him bringing on a ton of Obama people simply because they are part of his patronage network and Obama was a good leader/selector of talent. Biden's history shows his stands tend to blow with the direction of popular sentiment in most cases, not unlike McConnell. But I'd call Obama one of the best Presidents in the past century, so to the extent parts of Biden's administration is Obama 2.0, I don't have too many complaints, his ability to pass legislature

being hamstrung anyhow.

The whole last 8 years has turned me sour on presidential term limits. Obama would have won against Trump in a landslide. Taking him out was like removing Pedro Martinez or Randy Johnson from a game because of the pitch count when your bullpen is trash. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

If I had to guess the impetus for the timing I would guess that Hamas looked at the approval, funding, and volunteer boost Islamic Jihad got from their recent tangle with the IDF and decided they needed to boost their own credentials.

I would guess that Iran isn't wild about some larger conflict where they have to try to get more aid to Gaza, not when the Russians are paying top dollar for anything they can get their hands on in terms of weapons.

I also read a paper once though that suggested that Israel's highly effective targeting of Palestinian leadership actually created perverse incentives for lower level leaders in those groups to push for attacks. Basically, the groups in many ways operate like organized crime (also sometimes like legitimate states, it's a mix) and your ability to rise is contingent on vacancies opening up, which often only happens through death. But getting a leadership spot means opportunities for wealthy and influence. So younger guys with ambition have an incentive to push for attacks that don't otherwise make much sense because it will result in their bosses getting kocked off and vacancies opening.

This sort of thing gets increasingly noxious as groups get into the drug trade and prostitution, since that attracts another crowd. And this has certainly happened. Hezbollah and other groups has been seen in Latin America working as muscle/training for drug traffickers. Obviously, not everyone is on board with this sort of corrupting influence, but it's a way to make "dark money," the US can't shut down and the type of people who will traffick weapons for you are also the type of people who tend to traffick drugs and people.

What a mess. It does show though what an incredibly good idea it was to force all settlers out of Gaza earlier, back when the Israeli government was sane. -

Joe Biden (+General Biden/Harris Administration)

Fiasco for sure. I'm surprised the Dems voted for removal TBH. It would have been a good move towards forcing the GOP towards the sort of compromise politics they should be pursuing considering they hold just one chamber and on razor thin margins.

But apparently the GOP leadership has reneged on several previous compromises, so I can see why the Dems decided to let them deal with their own mess. Still, it isn't good, it makes a shutdown highly likely. And the idea that a "shutdown is good because Republicans will get blamed for it in an election year," is the same sort of politics that has destroyed the GOP's ability to govern.

It's insanity. It's going to be an absolute nightmare if Trump wins again, which seems quite possible. I really, really wish Biden would have stepped down. It seems the height of hubris for him to run again at his age, with his abysmal approval ratings, during one of the most consequential elections in US history. Then again, from what I understand, he basically got the nomination by threatening to stay in no matter what, giving the nomination to Bernie and thus, in his and his rivals' estimation, making a Trump victory far more likely (probably true). Despite the media blitz to boost his image, his actual actions at key moments make him seem a good deal like Mitch McConnell, e.g. "if I can't sit in the important seat I'd rather watch the ship sink."

But, on the plus side he's generally staffed the Administration with competent leaders, so my problems are more political than on policy. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West BankA pale echo of a previous successful surprise attack on the eve of a Jewish religious holiday. The 1973 offensive began 50 years ago to the day (Yom Kippur instead of the end of Sukkot due to how the holidays float around).

Then, Egypt could boast of some impressive initial breakthroughs, and was quite successful until false Syrian reports of their success up north goaded them out from beneath their SAM umbrella. The war ended in disaster. The IDF had pushed the SAA back into the Damascus suburbs in 72 hours, the Syrian MOD HQ was bombed to ruins, the Egyptian army encircled and open to destruction, and the way to Cairo wide open. But, it did open the door to long term peace because Egypt amazingly was still able to make their initial successes into political win. I don't see the possibility of that here.

You see a lot of other things in this echo. Here the early surprising success up from Gaza is a handful of destroyed tanks and shock that those who crossed the border were able to hold for all of six hours. Of course, Netanyahu is playing it up like it's 1973, but the dates are the only analogous part here.

The military situation is hopeless for the Palestinians. They are in many ways blockaded harder by Egypt than Israel for their role in the Sinai insurgency. Their leadership is far more fractured than in 1973. The other Arab states have turned on them, leaving Iran as their main ally. Syria is in ruins and in no position to assist them. Russian support can't approximate anything close to what the Arabs received from the Soviets in 1973, nor are the Russian's particularly willing to support Hamas openly, at best filtering aid through Iran.

If anything, this should underscore Israel's ability to make concessions because the balance of power is so far to their side, but I seriously doubt that's how it will be taken. It's a blunder by Hamas in terms of increasing the bargaining power of their side re independence and peace, but I've long come to the conclusion that a lot of attacks on Israel are more about infighting between Palestinian groups, jockeying for position, then a pursuit of long term independence goals, a sort of focus on being king of the rubble.

This is, of course, exactly what the extremists who rule Israel want.

On a side note, it seems like Hamas may have been given some effective ATGMs. They have a picture of at least one Kornet. The success of their drones early might have more to do with surprise than their ability to defeat AD though. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / Phenomenalism

No, I understood the distinction, you did a fine job describing it. What I was saying is this: were we able to manipulate our own sentience/experiences well enough, we'd probably also believe that that we understood it well enough to decide rather some AI actually experienced things or not.

For example, if I was hooked up to a machine and someone said "I'm going to press a button and you're going to experience enacting x exact internal monologue, feel happy, see a green pony walk into the room, then lift your arms up and yell "I love Newt Gingrich," and mean it," and the person pressed the button and all that actually happened, I'd assume that whatever technology they were using implied enough mastery of the causes of sentience that they could tell me if a given AI experiences it or not. The reason P Zombies are a problem, IMO, is that we actually don't have a good idea what causes sentience, and so we don't know what to look for to determine what things have it.

Now, of course we could always remain skeptical and suppose that maybe even rocks are sentient deep down, but I think this would be enough evidence for most people.

Predictive capacity is already implied in the philosophical approach.

Maybe sometimes. But it seems to be able to do without making distinct predictions quite a bit. E.g., Hegel's theory of history and institutional development obviously could be extended to make predictions, but he specifically doesn't do this, history being "thought comprehend in its own time," and all.

And I've never come across any phenomenology that tries to make the sort of predictions psychology does, although maybe that's selection bias.

This doesn’t make the scientific version more precise than the philosophical

Of course. Nor does it make it more accurate. "Garbage in, garbage out," as they say in the data biz.

But that's why I use the example of a technology that lets you interact with conciousness in a profoundly direct way. Perhaps "prediction," is a bit to amorphous here. Part of what makes the scientific view so convincing is that it allows for mastery of a phenomena. It lets you grab cause by the handle and shape things to your will. The proof is in the pudding.

It's the difference between gnosis and techne. You don't necessarily need gnosis, understanding, knowledge, to master something with the appropriate technology. But to be the one who makes the technology, that requires gnosis. The best proof of gnosis in most contexts? It's techne, mastery, the technique for manipulation. Techne is where the speculative element of gnosis is put to the test, "causal mastery talks and bullshit walks."

Which isn't to say you can't know things about phenomena and not be able to control them. Nor that people can't control phenomena to some degree while failing to understand them. But if you learn how to control them well enough, and you understand the techniques you employ, then it seems like good evidence that you understand the whole thing. It's the difference between advancing lift as a theory in physics on a chalk board and trying to convince people that way versus flying a plane over their head and yelling "ta-da!" Well, we might not think the Wright Brothers understand everything about lift, but we know they understand something important.

This is also why I think people expect saints and sages to behave in a particular way. It's something like: "you say you've reached a sort of special understanding of the world, achieved the gnosis. Ok, now show me how you've mastered yourself then." The ascetic practice plays an important role for the practitioner, to be sure, but it also seems to play a role as "proof" to the would-be student. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / Phenomenalism

Right, but it isn't just translation. We'd need some sort of very good predictive capability. Something like, "I'm going to run this program on the Neurostim 8000, but first I'm going to describe in very fine detail what it is you'll experience and think. Then I'll run it and you'll find that my description was highly accurate."

I think if we had something like the technology mentioned above, something such that someone could control what you see, the emotions you feel, and even the words of your internal monologue by "playing your nervous system like a piano," then most people would say we've sufficiently grounded the causal underpinnings of experience to be able to tell when something is conscious at a human level versus just appearing so, even if we can't fully explain exactly where that consciousness emerges on the level from zygote to new born.

Is such technology possible? That's another question. But if it ever exists, I think many of the questions around the hard problem will be effectively solved. -

The Mind-Created WorldBTW, it occured to me that a very similar set of problems addressed by this OP shows up in phenomenology through the debate about transparency and object intentionalism.

Are the contents of experience just what we experience? How can we describe an experience to someone who hasn't had it? Generally, when we try, when we try to explain sight for instance, we just end up explaining the things we see, colors etc., not the experience of seeing itself.

So is experience just a transparent window into the world? But if everything else interacts with the world the way it does because of its properties, then it seems a little strange that experience would lack any properties and be so transparent. Yet if experience does have properties, then it seems we should be able to divide it up, at least through abstraction, and talk about how the parts relate to the world.

And this gets to the issue of "indirect realism," as well. I personally am no big fan of indirect realism because it seems to suppose some sort of humonculous that "sees" the representations. But if its representation all the way down, then indirect realism turns out to be just the same sort of interaction as realism.

Transparency in phenomenology, while at first glance closer to direct realism, seems to me to have some similarities with indirect realism in that it supposed a unified whole, perhaps without properties, to which experience is "presented." And this sort of thinking seems to make it easy to fall into circles asking about what things are maps and what things are territories. -

Ukraine Crisis

Ah, like Iraq forced the US to invade it by violating US red lines? Or like the Poles forced Hitler to invade by violating his red lines? -

Implications of Darwinian TheoryI think it's a bit of an historical accident that evolutionary biology has become so tied to battles over religion. Basically, you had support for evolution and its popularization firming up around the same time that people began to notice some deep problems with the conception of an eternal universe paired with snowballing evidence for our universe having started to exist at some point in the (relatively) recent past. 14 billion years ain't much compared to infinity after all.

Evolution was seen as a silver bullet to put down creationist dogmas, and because creationists reacted poorly to the building support for evolution, trying to ban it from schools, etc. the two issues became tied together. But then evidence for a "starting point" for the universe was also seen as a big win by proponents of a "first cause," or "prime mover." Popular athiestic opinion had been in favor of an eternal universe to that point precisely because a starting point reeked of God. But aside from evidence for the Big Bang, problems like Boltzmann Brains began to crop up for the eternal universe.

And so the ideas seem to have become tied at the hip. The idea that evolution was a silver bullet for religion is born partly out of the religious reaction to evolutionary theory, partly because it had to become the silver bullet now that first cause was back in the popular mind. You see this today. Theists want to talk about the Fine Tuning Problem, the Cosmological Argument, Cosmic Inflation, etc. and militant atheists, your Dawkinses, etc. want to talk about natural selection.

IMO, these are completely contingent relations, and neither field has any special relation to evidence for or against a God. Plenty of theists have made their peace with evolution and evolution even seems to pair quite nicely with some views of God as unfolding dialectically, or views of natural teleology. But since evolution was historically a battleground over religion, it has remained one by inertia. And this is why we see "evolution as religion," . It is supposed, dogmatically IMO, that any theory of evolution necessitates that evolution occurs through "blind random chance" and thus it seems to preclude the possibility of purpose, cutting the legs out from most religious claims.

I agree this is a powerful force in modern science/scientism. Neurodarwinism was largely attacked, not because the processes it described weren't isomorphic to the process of natural selection, and not because it lacked predictive power, but precisely because "fire together, wire together and neuronal pruning are inherently interlinked with intentionality," and "evolution simply cannot admit intentionality." And you see this is similar arguments over whether lymphocytes production is "natural selection," if genetic algorithms fail to mimic real selection because they "have a purpose," if lab grown "DNA computers" actually "compute," and in Extended Evolutionary Synthesis.

I don't see an explanation for the strength of the dogma accept for the "religion-like" elements of how evolution has been used re: scientism. Maybe there is something I'm missing, but selection processes seem like they could involve intentionality or not and still be largely the same sort of thing. -

Neutral Monism / Perspectivism / Phenomenalism

Does the hard problem vanish or rather find itself replaced ?

I don't think so. The "hard problem," is the problem of explaining how consciousness arises and how it produces its subjective qualities through a scientific theory that has the same rigor, comprehensiveness, and depth as any other of the major scientific theories we are familiar with (e.g., explanations of cellular reproduction.) If that's sort of answer you're looking for, this sort of framing isn't going to help you.

Phenomenology might help us find an answer to the hard problem, or it might tell us that the answer we want is unattainable, but it can't answer the problem because the problem is about explaining the subjective elements of consciousness in the same sort of language/model that we use for explaining how a car works.

This seems more akin to the answer of eliminitivism, an attempt to dismiss the grounds for the question. Now, maybe the question is unanswerable, or maybe it is asked in the wrong way, but it seems to me to be a fairly reasonable question, so I don't think the difficulties we experience with it can be reduced to "pseudo-problems."

Other types of answers might be valid, but they aren't the type of answer the hard problem is about. We want answer that would tell us something like "do x and y and then z is exactly the thing you'll experience." I'll allow that this is quite possibly a bad question because it is impossible to answer, but it does seem to be a coherent and fair question. "Explain my mind to me like my mechanic explains how my breaks work," is meaningful at least.

Plus, even for the type of answer it is, it leaves me wanting more. Why these sensations and not others? Why do they follow each other in such and such a way? How is it so easy for me to think through what my future sensations will be based on my past ones? If the subject is a limit on the world, why such limits? If the being stream has a beginning, why did it start streaming and why is the stream like it is? And these sorts of questions seem bound to lead us into the same sorts of questions where the traditional thorny problems of philosophy lie.

If the world is one and the thinking subject is illusory, then there doesn't seem like there should be any barrier to explaining the appearance of the thinking subject in the same terms we use for all sorts of things in the world (e.g. how a TV works). But then that is just the hard problem repackaged as an explanation of appearance. -

The Mind-Created World

Absolutely. At one point, all of the universe was contained in one point, so it's unclear if there can be anything that fails to causally affect our experiences. That said, processes seem like they should be able to be more or less central to the emergence of mind, so the separation is one of degree.

Oh yeah, I like a great deal of what I heard from Mach. That said, I dislike the fact that he was among the progenitors of the big trend in philosophy to claim that "anyone who disagrees with me is saying things that are meaningless, and thus no response is possible." Claims of perfectly intelligible sentences being "meaningless" is a pet peeve of mine lol.

The ways-of-thought that accomodate the transcendent realm have by and large been abandoned in secular philosophy.

Yeah, it's a real problem. If I tried to trace its etiology, it seems to be tied to the drive to deflate truth and turn logic into a sterile study of "closed systems," that resulted from findings in the early 20th century. Faced with having to give up certainty, bivalence, or both, or having to make logic into an almost magical language cut of from the world that floats outside, "out there," we have tended to go with the latter. IMO, this is a mistake. And its funny that this choice was made despite the triumphs of naturalism and scientism, since it directly contravenes core pillars of the former.

---

On this wider topic, I'll have to return to finish Pinkhard's "Hegel's Naturalism," at some point. I recall thinking it showed some pretty good solutions to this whole bundle of problems. -

The Mind-Created World

Something I only discovered in the writing is that subjectivity is necessarily prior to awareness rather than the result thereof. It is of course a judgement by the organism in relation to itself as to whether a substance in the environment is beneficial or harmful to ingest. I don't know if others have looked at this, but it does seem to turn some thinking about awareness and consciousness rather on its head.

Indeed. I think it might be a mistake to think perspective emerges at life in the first place. The idea of a totally distinct "semiotic cut," occurring at the creation of life seems problematic for a number of reasons, not least of which is that the definition of life is incredibly fuzzy. This was the weakest part of Deacon's "Incomplete Nature," for me. The dividing line between autocatalysis and the emergence of autogens seems very hazy. It's not the type of progression that seems to lend itself to the distinct emergence of some totally new thing.

Further, perspective matters in very basic interactions. Scott Mueller uses the example of simply enzymes in his "Asymmetry the Foundation of Information." The enzyme will do its thing, interacting with a chemical the same way, regardless of whether the reagent in question contains isotopes for some of its particular atoms. The process is blind to the difference between isotopes. Such differences are, for this interpretant, a "difference that doesn't make a difference."

Mueller further uses the example of a detective trying to figure out if two diamonds have been switched. The diamonds are identical in every way except for one having a higher share of isotopes. For the detective, using all the regular tools of the jewel trade, the two diamonds are completely indiscernible.

Thus, perspective matters even in the most basic interactions. Entropy is another good example. Some differences make a difference in some contexts but not others. Information as difference is obviously context dependent, as when words are written in white font on an identical white background and fail to convey information.

Carlo Rovelli plays with a similar ideas with his relational quantum mechanics, although I think his model runs into problems if we take objects as fundamental rather than process. If the universe is a collection of substances, then we have a hard time explaining why some properties of objects should "snap into place" during some interactions but not others. This is similar to the problems some people have with idealism. "If things only exist as connected to mind, how do we explain properties coming into and going out of being." I don't know if this is a problem for process. It'd be like asking for (4 * 2) * 6^2, "where does the four go once we've moved on to doing 8 * 36?"

How intentionality and mental life emerges is a great mystery. But how perspective emerges seems less so. It's seems like it might be more something that is so fundamental that it is easy to miss, the way a fish doesn't notice the water in the ocean. IMO, it's been a mistake for people to conflate the "aboutness," of first person experience with the "aboutness," of how a computer interprets code instructions, or how a human organization (which presumably doesn't have its own qualia) interprets signals (e.g. international relations, how does "Iran" view the transit of US warships off its shores, etc.)

The last example is probably the best here. We don't think corporations and states have their own mental life, but they do seem able to posses knowledge and priorities that differ from the sum of their members' knowledge and desires (e.g. when the US security apparatus "didn't know what it knew" re: 9/11, but later uncovered this through intentional reflection). And the existence of such knowledge/priorities entails perspective and a form of aboutness, even though the first person "aboutness" appears to be absent. -

The Mind-Created World

But notice that as soon as you invoke them or gesture towards them, then already 'mind' is involved. All such conjectures are variations on the sound of the unseen falling tree.

Sure, but they might be very different from the abstract idea of "very causally disconnected stuff in deep space," that I have. Since everything is ultimately connected, the separation is one of degree, but it's still useful to distinguish between the stars whose light we see and processes that are much more proximate to the emergence of mind, which seems to have a "nexus" of sorts in bodies.

I'm inclined to say that the mind is never an object, although that usually provokes a lot of criticism. I've long been persuaded by a specific idea from Indian philosophy, namely, that the 'eye cannot see itself, the hand cannot grasp itself. The 'inextricably mental' aspect is simply 'the act of seeing'. Perhaps I might quote a translation of the passage in question. This is from a dialogue in the Upaniṣads where a sage answers questions about the nature of ātman (the Self).

I agree with this to a certain degree. We're blind to much of our cognitive processes, and far more blind than we tend to think. But I don't know if it makes sense to abstract "that which experiences," from experience in this way, and further to claim that this experiencing entity is a unity, rather than a collection of composite entities. It seems more to me like the unity of "that which experiences," is an illusion created by the same blindness that makes it impossible for mind to ever become fully object to itself.

That said, I think Ātman/Prakriti is a better division than Western "objective/subjective" in general.

Although it comes from a more eliminativist bent, I always found the philosopher/novelist R. Scott Bakker's "Blind Brain Theory," and "Heuristic Neglect Theory," pretty good on this sort of thing. https://rsbakker.wordpress.com/essay-archive/the-last-magic-show-a-blind-brain-theory-of-the-appearance-of-consciousness/

Plus, it seems necessary that this blindness must exist. If we had a meta eye that somehow recorded and represented to us everything that goes on in generating our experience of sight then we would still be blind to the activities of the 'meta eye,' and so not understand everything under-girding our experiences. We would need a 'meta meta eye,' for full cognizance of the meta eye, and then a meta meta meta eye, and so on. I think this inability for any one entity to fully fathom the ways in which it is cause while also being a source of effect is bound inextricably to basic elements of reality, the way being has a semiotic element, such that effects are signs of causes and only exist as such signs when they interact with a third system (Rovelli's Helgoland discusses this).

So my disagreement comes more from the idea of mind as being necessarily unified. Mind seems to be able to become, to some degree, object to itself only because the mind isn't an indivisible whole. It emerges from many overlapping levels of communication such that large, "conscious systems," (e.g. whole hemispheres of the brain) are to some degree "other" to each other. But this is a relation that seems to go all the way down to the most fundamental level. "That which experiences," seeming unified seems to be more an issue of how, if one looks into a mirror, one can see what is behind them, but not that which lies behind the mirror.

While it's true that we "can't get around the mind," it seems equally true that we both "can't get to (most of) the mind," and that we "can't get around the world," although we can abstract and retreat from it. It's in this that I worry about straight forward relations, such as "the mind creates the world." This is true, but the world appears to create mind as well," and the separation of the two seems to be, causally at least, more one of degree rather than kind. -

The Mind-Created World

Nice piece. It's a clear framing of a problem that is at the heart of modern "popular metaphysics." I find myself agreeing with what I took to be the main thesis here:

By investing the objective domain with a mind-independent status, as if it exists independently of any mind, we absolutize it. We designate it as truly existent, irrespective of and outside any knowledge of it. This gives rise to a kind of cognitive disorientation which underlies many current philosophical conundrums.

But I agree with the thesis for some different reasons I will touch on.

But what we know of its existence is inextricably bound by and to the mind we have, and so, in that sense, reality is not straightforwardly objective.

I agree that reality is not "straightforwardly objective," but more because of general confusion over what the term "objective," means. It seems to me like there is a strong tendency to conflate the "objective world," with something like Kant's noumenal realm. Thus, you might see a claim that the "objective world is reality-in-itself." This, paired with the positivist idea that "objectivity becomes equivalent to truth at the limit," unhelpfully muddles a number of concepts that are better left separate.

"Objectivity" only makes sense if there is the possibility of subjectivity. If there are no experiencing subjects, then there is no objectivity. If objectivity is not defined within the context of the possibility of something not being objective, then it is a term that applies equally to absolutely everything, making it entirely contentless. Truth is similar in this respect. What is the content of saying anything is "true," if "false" is not a possibility?

"Objective" is not a synonym for "real," "true," "noumenal," or "in-itself," and a close examination of how the concept has historically been used will demonstrate this, conflations notwithstanding. Objectivity is what we hope to arrive at when we try to eliminate the (relevant) biases of any particular point of view. But the "objective view," is still a view; it is not what we arrive at when we have no point of view (as you point out, this makes no sense). When we want an objective view of a phenomena we try to observe it in many different ways, using instruments, creating clever experiments, trying to overcome biases. If the objective view we were after was "what phenomena are like without a mind," scientists could just shoot up anesthesia and achieve something to that effect.

Objectivity also doesn't equate to truth either. Subjective experiences are part of reality and smoothing them out to create a more objective view is itself an alteration of our view of reality. The truth of the horrors of the Holocaust wouldn't best be described by a phase space map of all the particles in Europe for instance.

Further, these conflations are a problem regardless of whether one embraces idealism, physicalism, or dualism. I'd argue that it only seems to be a particular problem of physicalism because popular versions of physicalism seem to be particularly prone to falling into this bloated definition of "objectivity as truth," and as "the world as seen from everywhere and nowhere."

That all said, I think an objective view of existence is quite possible (views can be more or less objective of course). The mistake is simply to assume the objectivity makes any sense divorced from the concept of mind.

It is not solely constituted by objects and their relations. Reality has an inextricably mental aspect, which itself is never revealed in empirical analysis.

I'm not totally sure what is meant here. Are minds not objects that have relations, or is it only the individual's mind that is not an object to itself?

I might disagree if I am understanding you correctly here. While I tend to want to view the universe as one unified process, it does seem like some subsections of that process are far more directly involved in causing minds to emerge than others. That said, I agree that there is an inextricably mental aspect to all experiences of the world. This aspect is implicit in their existence as experiences.

However, it doesn't seem like everything that is experienced is necessarily all that closely related to the emergence of the mind doing the experiencing. Obviously, there is a relation, else how are the things experienced? But the relation between a person and a bag of drugs on a table versus a person and a bag of drugs they've just ingested is quite different because in the latter case the drugs are now much more deeply involved in the processes from which mind emerges. I suppose the thing that is missed in the prevailing view that you are commenting on is that even the drugs on the counter are part of the process that results in mind. Just because we can abstract the functions of a central nervous system from a specific environment does not mean it will function without an environment.

But this is where I might disagree: everything we experience is causally connected to mind, by definition. However, it seems possible to me that there might be distant processes that are far enough away from any minds that the goings on within them are quite irrelevant to any experiences. But I would still say its possible for these processes to exist. Now these processes are, of course, part of the larger, universal process that minds do experience, so their "separation" from processes that involve mind is an abstraction, subjective. But because this separation can be tied to causality, it isn't arbitrary, and seems as "real" a separation as any of our "natural kinds." It's in this sense that I would say "mind independent things" can be said to exist, although this independence isn't absolute.

Whatever experience we have or knowledge we possess, it always occurs to a subject — a subject which only ever appears as us, as subject, not to us, as object.

I'm not sure of this. It seems we can observe our own mental processes, making ourselves, or parts of ourselves, an "object of analysis." But mental life itself is a process, so I like to think of it more as sub processes looping around on a larger stream of process, sort of a fractal recurrance of the way in which mind itself is a process looping around in the wider universal process. And group minds might be thought of as another such "looping."

A corollary of this is that ‘existence’ is a compound or complex idea. To think about the existence of a particular thing in polar terms — that it either exists or does not exist — is a simplistic view of what existence entails. This is why the criticism of idealism that ‘particular things must go in and out of existence depending on whether they’re perceived’ is mistaken. It is based on a fallacious idea of what it means for something to exist. The idea that things ‘go out of existence’ when not perceived, is simply their ‘imagined non-existence’. In reality, the supposed ‘unperceived object’ neither exists nor does not exist. Nothing whatever can be said about it.

Right. Moreover, people often fail to realize how our discrete characterization of things into "objects" is itself the result of the mind. Empirically, the universe looks like a single process. There are no truly isolated systems. The "objects" we understand well appear to actually just be long-term stabilities in process.

To use your train example, the passengers absolutely would observe the wheels disappearing if they did disappear when everyone stops looking. They would feel their train derail and go skidding across the ground, which presumably people can see out the windows. The universe is interconnected. We don't have to directly observe things to have them be relevant to our observations. I have never directly observed two atoms fusing, but I see starlight almost every night, I've read plenty of books mentioning astrology, the history of the world I live in is shaped by people with political power making momentous decisions based on the movement of stars, etc. Thus, fusion, even that occurring many light years away, hundreds of millennia ago, is still something I observe the effects of. To paraphrase Bonaventure, 'an effect is a sign of its cause." Distant instances of fusion explicitly effect our experiences every time we even remember seeing stars. If you recognize how intricately connected cause and the process of local becoming is, it becomes silly to talk of things we know to exist "not being observed and so disappearing."

This is also a good example . We don't need to be able to observe photons in fiber optic cables to "observe" them. We would observe them doing their work or not doing it when we go to refresh our browser and it either loads or gives us an error.

I also don't know if I would agree with the "idealism" route though. Lately, I've been trying to figure out if there is even a distinction between "physicalism" and "idealism" once one steps outside of the box of substance metaphysics. If we accept that there is only "one sort of stuff," then process does all of the explanatory lifting, substance nothing, since it is uniform. Things being "physical" or "mental" substance becomes irrelevant. Nor does it seem like creating a distinction between "physical" and "mental" processes will add any sort of extra explanation if the two types flow into one another.

This does not mean the battle of the big 'isms is a "pseudo problem." But there is a posterior problem of determining if stability or change is fundamental. If change/process is fundamental, which I think appears more likely, then these old distinctions lose the purpose they were created for. If the universe is truly one unified process, and the universe clearly has minds, then it is trivial that there are no absolutely mind independent entities just as there are no truly isolated systems. "Mind creating nature" versus "nature creating mind" becomes simply an error of projecting artificial distinctions onto a unified causal process (although this doesn't negate the relevance of many philosophically interesting issues related cognitive science).

There is still the hypothetical question of: "Could a different universal process have come into being, such that it produced no minds," but this seems to be a different question. This isn't physicalism versus idealism, but rather the "problem of first cause," which remains for either ism. -

Is maths embedded in the universe ?

:up:

And of course the regularities of our world, the seeming logos for lack of a better term, certainly can be used to make an argument about the divine, either regarding its existence or its nature. That's the project of natural theology after all. However, I do not think the recognition mathematics, etc. as, in a way, existing in the fundamental fabric of being, at least as much as we can say anything exists, or even the recognition of some telos at work in nature, necessarily entails any particular theistic or religious attitude.

Like you say, any apparent all encompassing logos can perhaps be paired down into fairly sterile mathematicological idealizations. I don't think you get religion qua religion without the mystical/experiential elements, and that the fear of religion "creeping in the door," of the sciences is greatly overblown, at times a cover for religion-like dogmas.

For one example of an excellent effort on this front, there is Saint Bonaventure's The Mind's Journey Into God.

However, by a more excellent and more immediate method, judgement leads us to look upon eternal truth with greater certainty. For, whilst judgement and analysis arises through a reasoned abstraction from place, time and transformation and, thereby, through immutable, unlimited and endless reason, of dimension, succession and transmutation, there however remains nothing which is entirely immutable, unlimited and endless - apart from that which is eternal; and everything which is eternal is God, or in God. And, therefore, however more certainly we analyse all things, we analyse them according to this reason, which is clearly the reason of all things, the infallible rule and the light of truth in which all things are illumined infallibly, indelibly, indubitably, unbreakably, indistinguishably, unchangably, unconfinably, interminably, indivisibly and intellectually. And so, as we consider those laws, with which we judge with certainty those things which we perceive, while they are infallible and indubitable to the intellect of the one apprehending, indelible to the memory of the one recalling and unbreakable and indistinguishable to the intellect of the one judging, so, because, as Augustine says, no-one judges from them, but through them, it is required that they be unchangable and incorruptible because necessary, unconfinable because unlimited, endless because eternal, and, for this reason, indivisible because intellectual and incorporeal - not made, but uncreated, eternally existing in that art of eternity, from which, through which and consequent to which all elegant things are given form. For this reason, they cannot with certainty be gauged save through that which not only produced all other forms, but which also preserves and distinguishes all things, as in all things the essence holding the form and the rule directing it; and, through this, our mind judges/analyses all things which enter into it through the senses.

What exactly is wrong with the puddle's thought in Adam's analogy? The idea that the hole was made for the puddle is the most obvious target. But the puddle is still in the hole because of what the puddle is and what the hole is, and those seem like phenomena a sentient puddle might well strive to understand.

I don't know how well the analogy generalizes to things like the Fine Tuning Problem though because there the comparison cases seem to be as wide as "all conceivable, describable objects, and maybe inconceivable ones too." And I don't think the pivot to multiverses solves this problem in the least. You just move from, "why this precise universe," to "why this precise universe production mechanism." Because if all possible universes are created, a host of follow on problems show up. I think FTP actually gets at a broader set of problems with naturalism when it is stretched into the realm of infinite abstractions, problems which are currently very poorly defined, rather than being a simple fallacy.

To my mind, this is more akin to the puddle trying to get its bearings by asking, "what is a hole and why is it here? And do puddles make holes (which, to stretch the analogy to the breaking point, puddles do indeed make potholes for themselves to collect in when they freeze, in a sort of self-reinforcing mechanism)?" -

Is maths embedded in the universe ?

Most often I've encountered the question from people motivated to use the fact that there is math in the world, as evidence for the necessity of a God.

Not in my experience, but it might be selection bias. Certainly it is sometimes used to challenge the plausibility of "the universe is necessarily meaningless and valueless and anyone ascribing any sort of teleology to nature is necessarily deluding themselves." But this doesn't entail arguments in favor of any sort of explicit theism.

The best example of this view I can think of is Nagel's "Mind and Cosmos," which looks at significant problems in the "life is the result of many random coincidences and looking at them as anything other than random is simply to give in to fantasy," view. But Nagel is an avowed atheist. Likewise, Glattfelter's "Information, Conciousness, Reality," Winger's "Unreasonable Effectiveness," etc. don't seem particularly theistic to me.

They just seem to challenge some of the dogmas of a particular type of atheism popularized in the 20th century, which has made some pretty stark metaphysical claims about meaning, value, and cause. These claims are, IMO, more grounded in existentialism than many people acknowledge, and I think equating challenging them with "theism" has become a bit of a strawman in atheist infighting.

IMO, there is nothing particularly theistic at expressing awe at the regularities in the world. We appear to have a universe with a begining. So at one point, there was a state at which things had begun to exist before which nothing seems to have existed. This forces us to ask the question "if things can start existing at one moment, for no reason at all, why did only certain types of things start to exist and why don't we see things starting to exist all the time? Or if things began to exist for a reason, what was the reason?"

I don't see how this is essentially a theistic question though. It seems like a natural outgrowth of human curiosity, God(s) or no.

I think there is a parallel to this phenomena in history actually. Prior to the advent of the Big Bang Theory, popular opinion was that the universe must be eternal. Evidence for an origin point was itself considered to reek of a sort of corrosive theistic influence. But of course, that evidence piled up, and today I don't think most people think acceptance of the Big Bang Theory in anyway precludes atheism. I think it's possible you could see a similar thing with teleology, although I can't say for sure. Teleology doesn't seem to contradict atheism, just a particular brand of it. -

Metaphysics as an Illegitimate Source of KnowledgeMetaphysics seems inseparable from science to me. After all, aren't discussions about whether species really exist discussions about ontology, what exists? Isn't the question about whether heat is a thing, a substance, or a process, molecular movement, the same sort of thing metaphysics asks?

Metaphysics constantly makes reference to empirical facts and modern metaphysics often relies on findings in the sciences to make their case. Scientists advance metaphysical positions in their books all the time.

IMO the attempt to deflate and generalize metaphysics is a barrier to good metaphysics. -

Is maths embedded in the universe ?

Seems like six of one, half dozen of the other. If the regularities are there, then "what mathematics describes," is everywhere in the universe, even if "mathematics" is not. If we take mathematics only to be the descriptions, not the things described, then mathematics is still "embedded in the universe." It's just that the only place "mathematics" is embedded is within living animals. Then our problem seems to be "how did this totally new thing come to be embedded only in animals?"

Well, to my mind, the obvious answer is "because of the regularities in the universe," which is, of course, partly what mathematics is used to describe. And so, we've gone in a circle. But the insight that a sheep is not the sound of the word "sheep," nor our drawings of sheep, nor the mental image of a sheep we can call to mind," does not suggest that "sheep are not in the world." By the same token, it seems like what mathematics describes quite often is as readily apparent in the world as sheep.

Contra this position, we could say that humans are separate from the universe, e.g., . But how are they separate from the universe?

We don't seem causally separated from the universe. Falling trees kills us, we die without food, our thoughts vary depending on how much food and water we get, if we ingest certain substances they can have a huge effect on our cognitions, etc. Our capabilities for language, mathematics, etc., the things that are supposed to make us distinct from the world, can be radically reduced or essentially destroyed depending on how we interact with the world.

If we grow up locked in a dark room, and somehow survive, we'll have severe cognitive deficits and not exhibit these distinct phenomena. If we get a bad head injury, we can lose all these distinct abilities. If we are given a high dose of drugs, we might temporarily lose all these distinct attributes. These unique attributes then, seem to be causally dependent on our interactions with the world. At some point, when the anesthesia mask goes on and you start counting backwards, you stop counting because of what you're inhaling.

But all this close mind-body interaction seems to suggest to me that we aren't "distinct from the universe" in the sort of way that would allow us to develop mathematics, language, etc. in any of the acausal ways that would allow us to discount the question of: "how did the world cause us to have these abilities if they only refer to special things that are only accessible to human beings?"

The close link behind mind and body is, to my mind, one of the best arguments for naturalistic explanations of apparently "unique" human capabilities, some of which have proved to be less unique than we originally thought (e.g., arithmetic capabilities). -

The meaning of meaning?

An easy case is games. Games are obviously human, contingent things, No one would confuse them for platonic, eternal forms. Yet still, in chess, in the game's own terms, bishops move on diagonals axiomatically, not a mere matter of correlation. While, you might aptly describe the mental operation associating bishop and diagonal movement as correlation.

It's perfect correlation such that knowing "bishop" entails "moves diagonal." But this doesn't make games some sort of sui generis phenomena that cannot be analyzed in terms of other communications. The rules of chess evolved over time, pieces changed, the rules still change around the margins such that international bodies have just given up on codifying a "one true rules of chess." More importantly, no one learns chess unless they interact with it "out in the world."

Trying to look for the meaning of chess, the meaning of games, or the "meaning of language games," "in their own terms," is a mistake if it means studying them without reference to anything else in the world. It's like trying to study life while refusing to admit a role for chemistry. Chess is not the type of thing one learns about except through experience, and so how is the way the sensory system works not relevant to understanding how we understand things like chess?

In my op, what I was looking for was the conceptual basis of the word "meaning", in terms of the language.

Right, I would just consider if this is the correct question to ask for a holistic understanding. Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations makes a good argument we cannot get an understanding of language of the sort we might like from starting with language. Philosophy of language has gone around and around for a century proposing various mutually exclusive "all encompassing" theories of how meaning works, and none looks like a particularly good candidate. I'd argue that the fundamental mistake is to think of language as somehow special, not something that might be explained, to some degree, by semiotics, communications theory, biology, etc. The result is something like trying to explain biology without any reference to chemistry, astronomy with no reference to physics, economics without psychology, etc. This doesn't entail that the one is reducible to the other, it just means that understanding the higher-level phenomena requires understanding how it interacts with the lower.

Even neurally, correlation seems to fit best with the meaning of words. The comprehension of sentences seems like a more complex operation.

Not sure what you mean here, but evidence suggest that language isn't understood on a word-by-word basis. You can mess around with phonemes or letter ordering quite a bit and people still understand the meaning of the sentence, and they rely on body language and tone quite a bit as well.

Philosophy of language has all sorts of problems with puns, double entendres and Spoonerisms precisely because it tends to insist that the meaning must be "in" the sounds and symbols, or, if meaning is constructed, that there must be neat relations between words or sentences and "brain states," (supervenience thinking lurking in the background there), or that meaning must come down to sentences relations to timeless eternal propositions. It seems to me like you need an analysis in terms of all three. The sounds and symbols matter, the "construction" matters, and the ability to abstract meaning into propositions matters, regardless of the ontological status of propositions.

But in language's own terms, its neural instantiation doesn't seem totally relevant.

And yet a small stroke will leave a person babbling incoherently and not realizing that they are doing so, or unable to understand spoken language, or unable to name or understand the function of the objects they see. If meaning in "languages own terms," ignores the fact that understanding and communicating meaning are profoundly shaped by relatively small brain areas then it seems to be missing something quite essential. -

Is maths embedded in the universe ?

Is the observer not in the universe? If they are, then it seems like the observer should have a body. But then isn't mathematics embedded in the body of the observer, part of the universe?

In this sense, it seems like mathematics must be "embedded in the universe." So the question seems to be more "how did our mathematical intuitions and those of other animals emerge and did mathematics not exist in any sense prior to the first animal that possessed mathematical intuitions?"

Moreover, animal bodies have a causal history, and that causal history must be such that it resulted in animals that understand aspects of mathematics. Additionally, mathematical understanding appears to be something individuals can gain from interacting with the world. Someone locked in a room doesn't learn calculus. Someone with severe brain damage likely cannot learn calculus or remember the calculus they once knew. So what is the connection there?

If mathematics wasn't "out there," how and why did mathematical intuition become common to several organisms? If mathematics isn't anywhere in the world prior to this, what did this sui generis intuition emerge from?

Neoplatonism had a good answer for this with the three hypostases, and the immateriality/immortality of the soul, but unfortunately their ontology seems less and less plausible today because of the tight interaction of mind and body. -

Is maths embedded in the universe ?

Do we view the same phenomena or view similar phenomena that we call the same for the convenience of fabricating the kinds of objects that are amenable to mathematical calculation?

Both obviously. You might use many different tools to measure a single tornado, ground sensors, aircraft sensors, and satalites, each measuring different things, and then you might also measure many different tornados.

And then you can generalize from tornados to dust devils to water spouts, to vortexes of all sorts and see that there are some general principles that hold for all of them and some differences between each occurrence (or even in the same occurrence over time).

But of course no one mistakes a hurricane or a vortex in a river or even a dust devil for a tornado. If you've seen a tornado, and it's aftermath, it's fairly easy to ascribe to it its own sort of natural kind. Nothing else rips six story concrete buildings off their foundation like a child kicking over a toy. It's causal powers have a particular sort of salience. You can see why God picked one as a vehicle of the divine presence to overawe Job.

However, if you're studying vortices on Jupiter you might safely throw 10 meter wide vortexes in with 10,000 meter wide ones. The salience of size differentials there is less relevant to us. So, of course the types are "constructed," but they are also constructed in ways that are posterior to the advent of human beings, e.g. relevance to an ecosystem or the scale of the relevant system.

Karen Barad is among those who suggest that the geometric notion of scale must be supplemented with a topological notion of it. What this means is that scales interact each other to produce not just quantitative but qualitative changes in material forms.

I'm not sure what this means. I'm guessing something to do with local versus global changes? What would be an example of a qualitative change? Is this sort of like strong emergence?

That’s because the presuppositions concerning the irreducible basis of objectness which underlie mathematical logic guarantee that it will generate a world of excellently established facts. It fits the world that we already pre-fitted to make amenable to the grammar of mathematics. The very prioritization of established facts over the creative shift in the criteria of factuality demonstrates how the way mathematical reasoning formulates its questions already delineates the field of possible answers.

IDK, lots of phenomena seem to elude our attempts to understand them. If the world is so easily shaped by how we view it, why did so many discoveries have to wait for millennia before yielding to inquiry? That people in the West bought into Aristotlean physics for millennia did not turn our world into one in which Aristotlean physics held. Instead people had to invent epicycles, etc. to explain why the world crafted by thought did not correspond to the world of sensory experience. For a modern example, we could consider the causes of conciousness.

I'm not sure about mathematics necessarily entailing some sort of necessary objectness; it seems to me that process metaphysics works just as well with mathematics as more popular substance interpretations. Plus, mathematics allows for plenty of creativity, far more than the natural sciences I'd say. Hence why it is still often considered under the liberal arts.

I think the sciences are slowly moving away from the idea, exemplified by the periodic table, of pre-existing forms that reappear throughout nature. They are coming to realize that such abstractions cover over the fact that no entity pre-exists its interaction with other entities within a configuration of relations. The ‘entities’ are nothing but the changing interactions themselves, which tend to form relatively stable configurations. According to this approach, the world is not representation but enaction.

Agreed. Process explanations are replacing substance ones everywhere. The periodic table is more a classification of long term stabilities in process that are common in the world. This means it isn't, as originally thought, a map of primary substances. But such stabilities are still out in the world waiting to be discovered.

Obviously, if no one "enacts" the discovery it isn't discovered, but if you interact with helium it is still different from interacting with nitrogen. -

To what extent can academic philosophy evolve, and at what pace?

Exactly, but this is largely limited to the graduate level from course catalogs I've seen, and generally not targeted at majors outside of philosophy.

Even in publishing you see this bias. Routledge has its "Contemporary Introductions to the Philosophy of...," Oxford has similar publications, there are lots of competing introductions for metaphysics, philosophy of mind, free will, etc., but the philosophy of biology, physics, information, etc. stuff tends to presuppose a graduate level background in the relevant sciences. There are good handbooks published in this area, North Holland does a good one on the philosophy of complex systems, Routledge has them, but the Oxford "Very Short Introductions to," are the only true intro level guides I am aware of on the philosophy of specific sciences (they are good though).

I am assuming this has to do with the lack of classes offered. No one to sell text books to. ASU and Oxford have two of the broadest online philosophy programs for instance and they have just a single philosophy of science course, and these tend to be less applied views. -

The meaning of meaning?

There is certainly a difference in kind. The subjective element appears to be totally missing from some types of communications.

But the new kind seems to be "emergent from," the more basic. In support of this idea, I'd offer as evidence all the ways in which particular types of brain damage or disruption impede the ability of human beings to form understandable language or understand language (and often only one type of language, written versus spoken, gets disrupted). Think Wernicke's aphasia, damage to Broca's area, various disorders that allow people to draw objects accurately but not to name or describe them, etc.

So the new kind seems dependent on the correlative element.

It also seems to involve it though. There is a ton of information theoretic work on human languages themselves, the types of grammars we see versus possible types, bit flow across all human languages, etc.

So the new kind also seems to have some of the "work" it does explained in terms of correlation. And indeed, that languages must be learned also suggests that symbols need to be coordinated with past experiences or other learned concepts. -

To what extent can academic philosophy evolve, and at what pace?I've always thought philosophy programs might be able to resurrect their relevance in three ways: