-

Does solidness exist?Solidity is a phase of matter. It's observably distinct from the other phases. Think of an ice cube melting and then boiling off into vapor. So yes, it exists. Subatomic particles can not be solids, liquids, or gasses. They can only be parts of the phase.

Example: no one water molecule is a liquid or a solid, etc. Phases of matter are emergent phenomena. The phases describe relationships between molecules. Ice is less dense than water because of a crystalline structure that only obtains when the energy of the molecules is low enough that they aren't moving past one another. Lots of physical properties are like this, for example, resonance.

I think the mistake here is assuming that the properties of the large scale collections of microscopic things we see as the objects of everyday experience exist for microscopic objects just the same, but on a smaller scale. Protons as "bbs" is a good example of a bad analogy. BBs generally don't exhibit wave-like behavior for example; the analogy fails. It might be better to think of all such particles as local excitations of a field, but other analogies exist because none of our analogies work perfectly.

Very large and very small things behave differently than the medium sized objects we evolved to interact with. Phases are an example of where the analogy breaks down because phases are the macroscopic appearance of large numbers of relationships between microscopic things.

Arguably, only these relationships exist and "objects" are just a cognitive shorthand evolution led us to, a way of compressing huge amounts of information into actionable intel for survival. -

Doing away with absolute indiscerniblity and identityBTW, there is already a lot of work on relative identity, but this version gets around one:

Della Rocca invites us to consider the hypothesis that where we ordinarily think there is a single sphere in fact there are many identical collocated spheres, made up of precisely the same parts. (If they were not made up of the same parts then the mass of the twenty spheres would be twenty times that of one sphere, resulting in an empirical difference between the twenty sphere hypothesis and the one sphere hypothesis.) Intuitively this is absurd, and it is contrary to the Principle, but he challenges those who reject the Principle to explain why they reject the hypothesis. If they cannot, then this provides a case for the Principle. He considers the response that the Principle should be accepted only in the following qualified form:

There cannot be two or more indiscernible things with all the same parts in precisely the same place at the same time (2005, 488)

He argues that this concedes the need to explain non-identity, in which case the Principle itself is required in the case of simple things. Against Della Rocca, it may then be argued that for simples (things without parts) non-identity is a brute fact. This is in accord with the plausible weakening of the Principle of Sufficient Reason that restricts brute facts, even necessary ones, to the basic things that depend on nothing further.

The basic idea here is that if true indiscerniblity doesn't equate to identity, then you can have an infinite number of identical things in the same location as a single thing.

An information approach avoids this issue by reframing the scenerio. There is a finite amount of information that can be gathered about a finite object. Supposing that there is somehow more objects co-located with each other doesn't represent a problem here because it changes nothing. The maximum amount of information remains the same and it is the same information, so arguments about identical co-located objects, or a cat for each hair a cat has, co-located on one mat, are simply the result of bad framing.

There aren't multiples of anything. There is a finite amount of information that is arbitrarily described as a discrete object. This object changes its composition, relative relationships, and form over time, but we may still declare it to be the same object over time if it preserves enough morphisms/similarity. Indiscerniblity can be absolute in terms of some relations, and not others. Thus, the definitions here are arbitrary but still useful. -

The Christian TrilemmaIt's a strawman. There are other possibilities like:

1. The Gospels are not fully factual narratives. Jesus could be fully fictional or his actions and claims could have been edited.

2. You can be sane, not trying to be deceptive (lying), and still be wrong about something. Granted, in the case of Christ, this line seems less relevant, because we tend to associate claims of divinity with insanity. That said, it is a common fallacy to see claims or actions that the majority of one era views as insane, as denoting insanity in anyone who ever made those claims or actions. We would call most people who think they can work magical spells today insane, but history shows us lots of rational, intelligent people who believed they could work magic. This is the result of the status of science and philosophy in the eras they lived in, not insanity. Same goes for terrorists. We'd like to assume that anyone who would carry out indiscriminate mass casualty attacks is somehow insane, but research on terrorists shows that they are often rational, and in some cases even the most violent groups are also shrewd political actors. -

Getting a PHD in philosophyI would imagine it is a tremendous challenge to keep your morale up. It takes a long time and the pay is not much above the poverty level. In high cost of living cities, PhD stipends are downright unlivable.

You have to be willing to commit a lot of time to a job that is paying you less than you could make almost anywhere else. The light at the end of the tunnel?

Very grim. Even the top 10 programs in the world have pretty poor placement rates for students 5 years after finishing their PhDs. Philosophy PhDs are not very marketable and the market for jobs that require them is absolutely flooded with candidates. Hence, even at the very top programs many PhD candidates quit.

This is not unique to philosophy. It's possibly worse in English, and as bad in many social science fields. When I toyed around with the idea, looking at political science, my advisor told me to apply to Harvard, Yale, etc., the top 7 schools then, and not to bother otherwise because I would likely not be working as an academic without top end credentials, and would be better of just applying for research jobs with the degree I already had if they interested me.

Pay is also quite bad after you get out. Top schools might only pay adjuncts the equivalent of $18 an hour (it might be up a bit now) for full time work. Getting to put "a big name," on your resume is supposed to be payment enough. Ironically, pay can be a bit better in out of the way places. I teach community college classes for fun outside my regular job and make more hourly then adjuncts at the big name private school I went to. More recently, they've started having PhDs teach classes completely unpaid. It's the "unpaid internship," of the Great Recession era, returned for academics in their thirties who might have families to support. The idea is that you work for free to get valuable experience to add to your resume (something your 7 year advanced degree didn't get you apparently).

This isn't true for all fields. I know people who got their degrees in mathematics who got offered huge salaries at tech companies. You're much better off in areas of applied science. But humanities and most social sciences degrees are massively overproduced relative to the market for them. It's like a worse version of how law schools were 10-15 years ago, which is really saying something.

Philosophy could be a fairly health discipline. There is a lot of work philosophers could do in the sciences. You can see a world where philosophy PhDs could at least grab research positions in the ways people coming out of other disciplines can, but the field seems like it can be pretty backwards looking (from my view on the outside). "Here is the list of great names, philosophy is plowing through them one by one with no topical organization or attempts to relate the material to modern science." That's certainly how all my philosophy classes were in undergrad. And so it's sort of a dead field.

If people focusing on philosophy of mind came out with an equivalent of an MS in cognitive science or neuroscience, people focused on epistemology/philosophy of science did a bunch of practical work on research/experiment design, people focused on logic got the equivalent of a MS in computer science and learned to apply that logic in coding/creating new coding solutions, etc. it seems like the employment picture would be less grim. Some programs seem to do something like this, most do not appear to.

To make things worse, universities are not on a stable financial trajectory, so I imagine things will get worse before they get better.

So, very hard. Easier if you're independently wealthy or have a time machine and can go back to 1960-1990 for the old job market. See: https://80000hours.org/career-reviews/philosophy-academia/

Or look at the Daily Nous site. It has a whole section for philosophy PhDs to post jobs outside philosophy they got so that people have an idea of where to look for work.

I'm sure the classes can be hard, but I've found class difficulty has little to do with how high a school is ranked, or even the level of the class. I took a security studies core class for polsci PhDs where I was the only non-PhD student and it was incredibly easy (and not a great class). I had a few other mostly PhD classes and none were particularly hard. Meanwhile I had classes I took at community college that were graded brutally.

I chalk this up to supply and demand too. At the community college, the classes that were hard were prereqs for the nursing program. There was a ton of demand for the nursing program because nurses command high wages, due to lack of supply.

Instructors graded harshly because they knew they had to make tough discussions to allocate a scarce resource. In the PhD classes, admissions to the school was the scarce resource because it was ranked 8th in the US then, but once people met the bar for admissions, the goal was to try to make sure they got jobs, since that determined the program's rankings (weird flip in incentives there).

Even in some brutal quant classes where I'd get half the answers on the test wrong to some degree, and feel lost the whole time as the professors filled 20 feet of white board with proofs, then walk back to where he started his work and begin erasing so he could continue with another 20 feet of proofs, I still got an A- because the curve made 50% good enough. -

Understanding the Christian Trinity

But it is question begging to say that he is referring to different entities. The point is there are other interpretations.

The founder, the chair and the majority shareholder can all be the same person. The founder is not the same as the chair, and the chair is not the same as the majority shareholder - these are not synonymous expressions - yet they can refer to one and the same person.

Thus the fact someone refers to the father, son and holy spirit is not decisive evidence that someone is referring to three entities.

Sure, but generally if you're the founder, the chair, and the president, you're not going to say "the founder told me I have to go, but don't worry, he's going to send the chair to help."

Which is a point against the 3 = 1 position. However, on the other hand you have many references to a single God creating the world (but then again, also Christ's involvement in creation).

However, it's worth noting that there is an absolute ton of paradoxes when it comes to the idea of identity. Identity, as commonly defined, requires the satisfaction of:

A reflexive relationship, G = C

Liebnitz' Law: whatever can be said of G can be said of

That these relationships are necessary.

Necessary distinctness: if G is not x then this is true by necessity

The Trinity, inasmuch as it asserts that all three parts share an identity, fails to meet this criteria. That said, I'm not sure how big of an issue this is because it's unclear if the definition of identity has serious issues. There are tons of unresolved paradoxes that emerge from this definition of identity. Introducing the idea of relative identity solves some issues, but opens up others. Not being able to live up to the bar of a broken definition is not necessarily a huge issue. -

Understanding the Christian Trinity

That is the beauty though for some thinkers. The seeming contradiction is the great mystery. It's the conscious overcoming of contradiction through meditation and prayer that is the revelation (sort of the same idea behind some koans).

The difference between the Father and the Holy Spirit appear explicitly in Christ's words. He refers to them as different entities in the same sentence.

"But the Advocate, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, will teach you all things and will remind you of everything I have said to you." - John 14:26

Christ also defines himself as different from the Spirit.

"Anyone who speaks a word against the Son of Man will be forgiven, but anyone who speaks against the Holy Spirit will not be forgiven, either in this age or in the age to come." Mathew 12:32

All three mentioned as different entities:

"“If you love me, keep my commands. And I will ask the Father, and he will give you another advocate to help you and be with you forever—the Spirit of truth. The world cannot accept him, because it neither sees him nor knows him. But you know him, for he lives with you and will be in you." John 14:15-17, emphasis mine. There is "me" (Christ speaking), the Father, and the Spirit, who is "another advocate."

I would also point to Paul's description of Christ's role in creation in Colossians, when paired up against the creation story of Genesis I. There, God's Spirit is mentioned as distinct from God, as happens often throughout the Bible. God (or the Spirit) speaks creation into being. Creation is effected by words, and Christ is the Logos/Word.

The interpretation of this go back to the early church. See: Basil the Great Hexaemeron 1.5, Ephrem the Syrian, Commentary on Genesis I. Origen has a take similar to this, but was condemned as a heretic; the Trinity shows up in heterodox theology as well. Obviously, the doctrine wasn't universal, or we wouldn't have the spread of Arianism, but it was common.

I don't think politics drove the acceptance of the Trinity. The Trinity emerges as a doctrine due to Christ referring to the Father and the Spirit as distinct entities throughout the Gospels. The doctrine was enforced to the exclusion of others due to politics, but it's present in Paul's writing, and explicit in early theologian's writing, before the Church had much political capital at all. -

Speculations in Idealism

The argument for natural selection as driving the creation of complex organisms isn't based on empirical findings in biology. He is using natural selection as a general theorem. The concept is applied in many ways outside of biology. For instance, we see the type of elements we see because elements above a certain size are selected against; they are unstable. Potentially, we see the type of universe we see because black holes generate new universes and so universes with physics that generate singularities are selected for (a speculative idea, for sure, but one that shows how wide natural selection can be used).

The argument for natural selection is merely that it is a theorem that describes how great amounts of complexity can arise without a designer. Consciousness is very complex. Consciousness arising from natural selection requires fewer entities than consciousness arising from an intentional designer (God). So, parsimony, Ockham's Razor, suggests natural selection as the driving force behind the complexity we see in consciousness.

As you can see, the theorizing comes down to deduction and observations of consciousness, not observations about the world as it is. I'll admit this reasoning seems a little weak, but since it is meant to convince people who don't agree with Hoffman's view on our relationship to the noumenal world "out there," I think it is strong enough. After all, if you reject Hoffman's reasoning here in favor of the idea that we do have solid knowledge of the noumenal world, then the arguments of fitness versus truth theorem still hold (indeed they seem grounded even better), and so you end up back in the same place.

Likewise, we don't need experience of external object to decide that our consciousness is finite. That comes from experience, but experience of consciousness itself. Same for our experience of what appear to be external objects. We know we get a finite amount of information from them because we can look at a poster from far away and not see a bunch of text in the lower left corner. When we get closer, we can now make out the text. This is an observation of incomplete information existing in consciousness; it applies even if you totally reject the external world. If you take the step of positing the external world, you're still going to have that observation that not all information about objects make it to experience, i.e. that our perceptions are finite and do not admit all information about those objects. But these points can all be proved by observations of consciousness itself, without any appeals to the external world.

But you're right, this whole model misses crucial details. Information theoretic approaches to cognitive science suggest a mechanism by which we can have perceptions that derive some of their content from "things-in-themselves." However, I think this doesn't necessarily kill the theory. Sure, some of the content of our perceptions is from those things, but if we lack a clear ability to define which information that is, if we can't track the morphisms that survive the long process from light waves bouncing off an object to our experience of sight, then I think his argument may still hold. -

Understanding the Christian Trinity

He has a good version of the idea; the concept existed long before him in theology and philosophy in various degrees of formalization. -

Speculations in Idealism

I see now. My reference to information was simply that we assume that organisms are not infinite. It's not that objects in the enviornment contain infinite information, it's that organisms lack infinite capabilities for storing information, and thus face limits and tradeoffs vis-á-vis information storage and computation speed.

There is no way for him to prove our representations have no counterpart in nature. He doesn't know what the full reality of an object is, and he knows we get information from the object. So how is he going to prove that there is nothing in the perception that sees *something* about the object?

I covered this earlier in the thread. There is no logical necessity to have a complete definition of p to show what p cannot be true of p.

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/716647

You earlier said yourself that we might sense some of reality and that is all I'm saying. If I see a car I see it for real even though there is much we can't see. So maybe we are on the same page.

I'm not totally convinced with his argument, so yes, I think we're somewhat on the same page. But I do agree with his point that the "car" does not exist outside our minds. The relative ratio of information in our conception of the "car" that comes from the "object itself," appears to be:

1. Very low.

2. An extremely small fraction of all information contained within the object.

3. Filled with semantic meaning, and filtered through concepts of space and objects that have no connection to reality.

The further issue is if thinking of objects "as they are themselves," is erroneous in the first place. In an informational analysis, the phenomena of the car only is as it interacts with the enviornment, and as its parts interact with each other. -

Pantheism

You might like "Information and the Nature of Reality," which Davies edited with Niels Henrik Gregson. Good combo of articles on information theoretic approaches from physics, biology (some by Terrance Deacon, who I always appreciate), semantic information/consciousness, and even theology at the end.

It's my late night book for when Floridi's Philosophy of Information stops making sense. That book is good too but very technical. I am regretting getting it instead of his Routledge Handbook of the Philosophy of Information, which is apparently more accessible.

I never liked these "arguments from psychoanalysis." For one, they can always work both ways. I've seen it that most physicists misinterpret the delayed quantum eraser experiment because they are emotionally invested in free will (which often gets conflated with experimenter free choice in these arguments). Superdeterninism is the logical conclusion and neatly deals with no locality to boot; dissenting opinions are due to emotional immaturity.

But then exactly the opposite charge is made by partisans on the other side. People commited to super determinism, who assume every measurement that would ever be made was specified "just so" during the Big Bang, are the ones who are letting emotion dictate reason. They can't handle non-determinism, and so they look for any conceivable gaps to keep it alive.

With arguments for or against the myriad conceptions of God, I've seen juvenile and mature arguments on both sides, with varying degrees of merit. You can also come up with all sorts of emotional reasons that people want to deny any conception of God and then project that on to athiest arguments as well.

For my money, I think the fact that very accomplished scientists and thinkers, who show every sign of being open minded, can dedicate their lives to this question and still come to different conclusions (or switch sides throughout their lives), should give us pause when looking for simple descriptions.

The ontological "It From Bit," thought experiment fits what you're describing. It's hard to see how observations would differ if it was somehow "true" or if it was merely an artifact of how we interact with the world.

But the larger model is useful when applied to other, more limited thought experiments. The big one I'm aware of is Maxwell's Demon, which haunted physics from 1867, to 1982, when Charles Bennett came up with an answer that made most people happy (lately, this answer has come into question). Here the information theoretic question was essential for determining why the Second Law of Thermodynamics couldn't be violated. Information Theory informs understandings of Leplace's Demon, the entity which knows the exact position and velocity of all particles in the universe, and so can retrodict the past and predict the future. Such an entity turns out to be impossible because information is only exchanged across surfaces, and so the Demon has no way to attain this information, while at the same time, said demon would need an energy equivalent equal to the algorithmic entropy of the entire universe, and thus would presumably have to be close to universe sized to avoid collapsing into a singularity.

But as interesting and useful as It From Bit is, it seems like we should be cautious about thinking we've hit rock bottom. Every time mankind makes a technological leap, we seem to theorize that the universe and our minds are set up like our most advanced technology. For the ancient Greeks, the universe was like stringed instruments and their new geometry. After Newton, the universe was like a great clock. In Maxwell's time, the universe was a great steam engine, and entropy was the primary concept for understanding it. Now we have a universe in the image of a computer, with the caveat that most theorists say the universe is really in the image of a quantum computer, which is still in its infancy, making the comparison fraught. Each of these new ways of thinking hits on certain essential truths, but none has proven complete so far.

I'll admit that I find it hard to see how to reduce things beyond 1 and 0, but intellectual history seems to have plenty of examples of how reality has been winnowed down to 1 and 0, only to be expanded again with new findings, just to collapse into binary again. I won't hold my breath on having hit bedrock this time. -

Speculations in Idealism

the argument that the tree is infinitely complex and hence not comprehendable still intact?

I'm not sure what this is in reference to. I was talking about Donald Hoffman's book The Case Against Reality. Are we talking about the same thing?

His argument about being able to see reality "as it is," is about how natural selection will favor a sensory interface that represents fitness payoffs, not truth. Not that things are infinitely complex and thus not able to be represented accuracy. The starting point for the work looking at fitness versus truth theorem is that entities are finite. -

Speculations in Idealism

My take is that he is fairly close to Kastrup in the final chapter of the book.

I think. Part of the problem is that you spend 90% of the book with the Hoffman who is still committed to an objective, mind independent world "out there," and then only get a short time with the idealist Hoffman. Most of what he's focusing on in that last chapter is how you can have an idealistic model that can be used in science, a model that makes empirical claims and predictions. So the ontology is a bit fuzzy.

Unlike Kastrup, who is fine leaving science mostly alone as a methodological system, Hoffman thinks ontological baggage from mainstream physicalism has bled into the sciences and is halting progress there. That makes his goal much different, he wants to find a way to radically shift our intuitions, but to do so in a way that can be modeled empirically and can directly inform science. I'm not sure if I agree that this makes sense. It seems like he is in danger of mixing the methods of science and ontology too much, the same thing he is accusing the mainstream of doing, but again, it's short, so I'm not sure.

I don't think I understand the objection here. Are you saying, "if mental entities are ontologically basic, why are they finite?" Why wouldn't they be? -

Speculations in Idealism

Hegel, following Schelling, had a philosopher of nature. He believed the world was real, not a simulation. The real world comes from the spiritual Absolute but matter is matter for Hegel. If Hoffman is correct, then all of science has been refuted and so why follow science at all anymore? As far as I can see that is the conclusion.

This sounds like a misunderstanding of the theory, which might be my fault because I was trying to explain it. The theory is not that the world is a simulation, nor does it refute or attempt to refute science. Science is ontologically agnostic; it's a mistake to assume that a theory that attempts to replace physicalism is somehow attempting to supplant science.

Given the degree to which the teaching of science is uncritically grounded in physicalism, I can get how it seems that way. However, the worst the theory is saying vis-a-vis popular physicalist conceptions is that a lot of the entities of science are useful fictions. But this isn't anything new in science, physicalist or not. The "laws" of science are useful fictions. They are idealized mathematical representations of how observations behave. Cartwright uses the example of Newton's laws for this point. The laws don't actually describe how gravity works for classical objects, they describe how gravity works for two idealized objects, which is good enough for most purposes. Add another body into the mix and you get the "three body problem." A gene is an abstraction, a "fundamental unit" of heritability, but it it's not supposed to be an elementary object. It's a fiction, or maybe a better description is "a type of mental shorthand" for an idea that is useful for theories. The mistake, for Hoffman, is in assuming that these bits of mental shorthand are the fundamental objects of reality.

Nor does the theory say that matter isn't real. The theory is grounded in empiricism and we have plenty of observations of what we call matter. What it's doing is pivoting around the ontological baggage that is attached to the "idea of matter." -

Currently ReadingThis a really neat (and free) book I came across just looking at the free books on Amazon for my Kindle.

It's also free from Springer: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-03633-1

Information—Consciousness—Reality: How a New Understanding of the Universe Can Help Answer Age-Old Questions of Existence is a dissertation that looks to summarize all the "big ideas" of human knowledge. It starts from how mathematics can describe reality and allow us to make predictions about the world. It divides the methods of mathematics into two categories, the mathematics of the continuous, which we use in our universal laws, describing symmetries, etc. and the mathematics of the discrete (graph theory, chaos theory). It also has a lot on epistemology and the philosophy of science. Basically, it's a big picture look at the edifice of human knowledge, with a focus on the twin "revolutions" of information and chaos. It even goes a bit into markets and politics (applying insights from earlier sections on mathematics, philosophy, and physics), and niche areas like cryptocurrency.

Then part two looks at all the problems with knowledge. All the ways what we can know is fundamentally limited, Hume's argument against induction etc.

The last part is authors foreword looking vision of how our knowledge could progress. Going off the summary he gives to start (haven't made it to the end), he focuses more on the potential fruits of information science, hence the title.

Really seems like a great summary resource.

Also reading The Lightness of Being: Mass, Ether, and the Unification of Forces. It focuses on how matter, particles with mass, emerge from energy. The other big focus is on the energy content of the "vacuum" and all that goes on there. It includes a really good attempt to explain quantum chromodynamics and quarks intuitively, although it is really hard for me to wrap my head around local symmetries. The explanation of how an area of (mostly) empty space (which may not exist like we think it does) produces quark condensate, generating quarks from nowhere because their existence is more stable than their not being, is very good too. A lot of intriguing questions on what the vacuum is (definetly not empty space) from a Nobel laureate doing his best to make this stuff intuitive, great stuff.

And I read Hoffman's The Case Against Reality recently, which is already discussed in detail in this thread: https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/720043 -

Understanding the Christian Trinity

There is no distinct passage in the Bible that spells out the Trinity, although the idea of Christ, the Father, and the Spirit as three distinct entities is definitely in the Bible. But so is the idea that Christ is eternal and took part in creation (John, Colossians).

Every theology book I've ever readily admits that the Trinity is not explicit in the Bible but is merely implied. Not all Christians are trinitarians. Early in the church there were a lot of non-trinitarians, but the success of the Church in consolidating its control on doctrine in the early middle ages meant that these groups became marginalized and disappeared over time.

Non-trinitarian groups have sprouted up throughout history though and there are certainly many today. Some even exclude Christ from the Godhead and have him merely as a subservient figure. However, these types specifically mostly date to the early church when there was no one set canonical Bible. Once you have John and Paul's epistles in the Bible, it becomes hard to argue against not only the divinity of Christ, but his eternal nature (given you accept the Canon, not all Christians do). Christ is also not part of the Godhead in Gnostic Christianity, but is normally framed as an Aeon of the Pleroma, like Sophia/Wisdom, and thus an emanation of the ineffable Entirety/Monad. Hell, in some versions of Gnosticism, Christ is the snake in the Garden, sharing the Fruit of Knowledge to save humanity from the evil demiurge Yaldaboath, who is the "God" that creates the material world in Genesis.

That all said, there is a whole ton of justification for the idea of the Trinity throughout the Bible. Just throw it into a search engine. -

Speculations in Idealism

Ha, so you were more correct about Hoffman than I. I had read about 90% of The Case Against Reality by this point, before getting distracted by Wilczek's The Lightness of Being.

In the first 90% of the book, Hoffman is making an argument against physicalism from a physicalist perspective. He keeps pointing out his commitment to the existence of the noumenal. I got distracted because, like many popular science books, it turned into a literature review of famous studies, showing how each supported his propositions. Good backup to produce, but it can get a bit dull, especially after the opening arguments had been so interesting.

In the last small bit of the book he radically switches gears and proposes a totally idealist ontology. It's a mathematical model that has finite conscious agents as its ontological primitive. Each agent posseses a measurable space of different possible experiences and decisions it can make, which can be described probabilistically. This allows theories based on the model to be tested empirically. Decisions by any agent change future options for decisions it will have, and agents interact by changing each other's options and experienced, so these units are Markov Kernels in the model.

A key point to recall here is that, while of course we observe unconscious things like rocks, i.e.things that are not conscious agents, the fact is everything we observe is unconscious. When we observe another person, we observe our icon of them. The icon is not sentient, it is our representation.

The ontology recalls "It From Bit," in some ways to, with the idea that complex conscious agents with a wide menu of possible experiences and decisions would be composed of simpler agents. For example, the odd behavior and experiences of people with split brains is because a more unitary agent has been separated into something closer to two agents in many ways. At the ontological bottom of the model would be agents with just a binary selection for actions, and binary information inputs. This allows for the possibility of a neat tie in to information theoretic versions of physics and the participatory universe concept.

His claim is that such a model can make empirical predictions, and could serve as a basis for working up to our laws of physics, and describing evolutionary biology. That's a big task, but I see how it seems at least possible in theory.

In the last bit, he gets into the concept of an infinite conscious agent that could be described mathematically. This infinite agent would have little in common with the anthropomorphic deities of many religions. Such an entity could actually be described mathematically, but it would not be omniscient and omnipresent, etc. Rather, it has an infinite potential number of experiences and actions. He poses the possibility of a scientific theology of mathematical theories about such infinites. This, to me, sounds like the Absolute, and he does mention Hegel by name in the chapter.

Neat stuff. A bit jarring to have it at the end, although I get why he did it that way. If he started with it many people would drop the book, and there is value in his critique of current models even if you think his model is nonsense. It's a little disappointing though because I'd rather have more material on the theory at the end, but I also see how creating such material is incredibly difficult. It's likely a task akin to the heroic (and somewhat successful) attempts to rebuild the laws of physics without any reference to numbers, totally in terms of relationships. If anything, his idea requires an even larger rework of how we think about things, but the payoff could be considerable if it allows us to make new breakthroughs in the sciences.

So, you were right, I was wrong. I do still like his initial framing, which keeps the noumena, more in some ways. It seems way more accessible to the public at large.

Side note;

Like Katsrup, he denies that AI could be sentiment. I don't know why this bothers me so much. But it seems like, if we get AI that can pass a Turing Test, which we may well get to this century (GPT-4 is coming soon), this standpoint is going to open a huge philosophical can of worms. I don't see why an idealist ontology that can allow for new life being created through sexual reproduction should necessarily have such issues with life being created synthetically. Because, even if we never get to fully digital AI, the idea of hybots, AI that uses both neural tissue and silicon chips, could get us there. We already have basic hybots, for example, a small robot that moves using rat neurons. But then you'll end up with the question of "how much of the entity needs to be composed of neurons versus silicone for it to be sentiment," which seems like it will lead to arbitrary cut offs that don't make sense.

All in all, I am not totally convinced by his solution to the problem he diagnoses, but I like it way more than the Katsrup model in the Idea of the World. I need to take a break from these sorts of books, they're going to end up converting me. -

"Stonks only go up!"

For sure, I didn't mean to imply it was one thing. I just wanted to point out the relationship between mortgage rates and home prices. Lower rates push prices higher. Arguably the single biggest factor aside from population growth pushing home prices up for the past 20 years is computers and the automation of tons of legal work that used to be done by hand. Houses as an asset have become incredibly more liquid, which has caused investors to poor into the asset class. The time it takes to sell a house becoming so much shorter makes its liquidity premium go up significantly.

My main point was simply that low rates are generally seen as good for working class people. This isn't necessarily true. All else equal, if you expect rates to fall in the future, you may be better off with a high rate and lower principal on your mortgage.

The Fed has historically been staffed by appointed specialists. It also has a great deal of political independence and insulation from public opinion. I think this explains the better performance.

Unfortunately, monetary policy can only move the needle on things so much. Fiscal policy needs to be a major mover in any solution.

US elections systems are almost tailor made to result in legislators who are significantly more radical than the median voter. Add in the blisteringly short two year election cycle, first past the post, winner take all voting that stifles third party competition, and the undemocratic structure of Congress, and it is a recipe for deadlock and political chaos. Demagogues have a significant advantage in the closed, first past the post primary system for selecting party candidates and the skillet for winning elections is not the same as the skillet for governing.

Ironically, the system wasn't set up this way. The Electoral College and the power of state legislatures to pick senators was designed as a check on "the will of the mob." Now those capabilities help the mob keep the GOP alive as a viable rival to the Democrats, even though they have won more votes in just one national election in almost a third of a century (and that one they won with the benefit of an incumbency from an election where they received less votes, and still won by a very narrow margin).

But I think the problems with these very old institutions have given us the wrong idea. The solution is seen as more direct democracy. I don't think this is the best idea.

Every study I've seen shows that appointed professional city and county managers tend to perform better on virtually every metric than elected mayors and commissioners. To be sure, there have been corrupt city managers, but they're much less likely to have corruption issues than mayors. Cities with city administrators and CAFOs, essentially city managers appointed by the mayor instead of the local council, also drastically improve outcomes. We also see how much better the Fed preforms than Congress.

To my mind, it certainly makes sense that this would work just as well on larger scales. There are other changes we need, instant run off or even closed list voting, open primaries, easier access to voting, the Wyoming rule to make House representation based on equal population again, representatives for DC, etc. However, a big change for the good would be replacing first past the post popular elections for governors and the presidency with appointed professionals. You still have elections, just like the city manager system, but the elections are for a small executive council to pick the governor or president. And I do mean "small," over 13 people or so you tend to start getting factionalism and less quality debate.

The executive council gets to pick the executive and then also act as advocates of their constituency to the executive. The executive is picked based on professional credentials for a specified term. They can also be removed by the council, normally with a slightly larger share of the vote (e.g., seven votes needed to appoint a leader, 9 needed to remove them). Rather than term limits, one way to deal with incumbency inertia is to raise the number of votes needed to reappoint a popular leader over time. So you might need just 7 votes for the first two terms, but then 9 for term three, and 11 for term four, and unanimous consent to continue on after that. This avoids the problem of term limits cutting out high quality leaders.

Side note:

I think the downsides of term limits really showed with the election of Donald Trump on extremely narrow margins verses an historically unpopular Democratic candidate. There is little doubt Barack Obama would have steamrolled Trump on a way to a third term and he is a leader who I think improved over time. Nor are three term candidates likely. We had one person make it past two terms in all the years it was legal to go over two terms. Since then, only Reagan and Obama had solid shots at winning a third term. Reagan likely would not have run again anyhow due to dementia issues, but even if he did, he'd be resigning and giving power to Bush, the guy who succeeded him anyhow. Obama had his faults, but was a very steady leader during a tumultuous time, and while alternative history gets murky the further you go out, I can see us in a much better place right now if we was settling into his fourth term. -

Understanding the Christian Trinity

Interpretations vary widely, so rather than try to offer a summary of a very diverse field, I'll just try to put forth my own understanding.

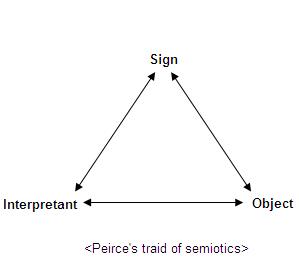

The Trinity is a representation of Pierce's semiotic triangle.

God exists in this way because, in order to exist onto Itself, It must contain these necessary relations.

The Father is the object. The name given to Moses, "I am that I am." The Father is the ground of objective being, the thing-in-itself. You see this through the numerous references to the Father creating and taking action in the "physical" world.

Christ is the symbol. Christ is the Logos (see: the opening of the Gospel of John and a similar passage in the opening of Colossians). Philo of Alexandria is good example of how Logos was interpreted in this period. The Logos is a universal reason, the laws of logic, of cause and effect itself. Man shares in the image of God in that he possesses some portion of the Logos. Man exists within the circuit of cause and effect, but can understand these laws (which is a condition for freedom).

In Romans 7-9, Paul discusses dying to sin. He speaks of how he loses a war with the members of his body and becomes dead in sin. This is obviously not a physical death, Paul still lives, but rather a death of personhood. It is no longer he who lives, but his animal desires. He is driven on as an effect that does not apprehend its own causes. He is then resurrected (again not biologically) in Christ, the Logos, and set free by the ability to apprehend what moves him.

The Spirit is the interpretant. It is Atman, that which experiences the symbol. The "Spirit of God," in the Tanakh uses the Hebrew word ruach, which means "wind" or "spirit." Ruach is also the Hebrew word used in the "breath of life," that enters living things (all living things, not just man).

There are two creation stories told back to back in Genesis with different details. In the first, the ruach of God, the Spirit, is hovering over the "Waters of the Deep." The Waters of the Deep are somewhat like Greek primordial chaos. A vaccuum of nothing, but a nothing packed with all possibilities, but since there is no definiteness, this all encompassing something is total abstraction, and thus not really anything. I'm using the more modern language of Hegel here, but the ancient understanding contains the same basic conception of a sort of "pregnant silence."

At the opening of Genesis, the Spirit is "above" this "full vacuum" and creates the world by speaking (through symbols). A lot of the Patristics saw this as the role of Christ in creation, as the symbol giving meaning to the things of creation. The pattern in which the Spirit utters things is very interesting, and there is a great book called "The Beginning of Wisdom," that covers the intricacies there, but I'll pass over that for now.

So, that's the start of Genesis, the Spirit of God speaking pregnant vaccuum into being. What do we get next?

Another creation story! But this time God is forming things out of physical dust. Man is shaped of clay and ruach is breathed into him.

The two stories make sense as viewing different relations between the triad of the Godhead. Things are created for the interpretant through symbol, whilst the objects being formed gives rise to the names of things (genesis of the symbols) in the second story.

God has this triadic structure because it's a basic necessity of being, part of what it takes to get "somethings" from the Waters of the Deep.

If I have time I'll try to add my exegesis and references to support this interpretation later.

Some traditions focus more on the historical Jesus, Jesus as a man, more than others. This makes it hard to square the Logos with the Christ who is the "Son of Man." I won't get into this much, except to recall one of the sayings of the man Jesus when a crowd asks him about how he can know Abraham when Abraham lived long ago, which is: "before Abraham was, I am." The mixing of tense, which recalls the idea of the eternal, is in the original, and it also recalls the name of God given to Moses, "I AM THAT I AM." -

"Stonks only go up!"

The Fed raising interests rates won’t change a thing. Except make the 90% more poor and make it harder to buy a house and take out loans. It’ll saddle even more people with ridiculous levels of harder-to-pay off debt.

Research on the effects of long term low interest rates appears to show that they are a major driver of inequality. This is something that was only investigated recently, because low rates were thought to be fairly benign.

High interest rates aren't the worst thing in the world. Think about the effects on housing. When interest rates on mortgages fall, home prices get bid up because people can afford larger mortgages. What we saw early in the pandemic was historic, rock bottom interest rates helping to spike home prices. Now, would you rather have a large principal at a low rate or a lower principal at a high rate? If your monthly payments are equal, you might want the higher rate because you can refinance when rates fall. You're stuck with the high principal and if prices fall you end up underwater. Yes, you build equity faster with a lower rate, but the trade off is less opportunity to refinance, which in some cases is not in homeowner's favor.

In terms of other asset classes, I'd argue the middle class is much better off with higher rates. They can get out of the stock market, where they are at a massive informational disadvantage, and get their yields from bonds. There is also the nice advantage of bonds actually generating economic activity, while money thrown at equities outside new offerings does very little to generate investment. -

"Stonks only go up!"

Good quibble. Yes, I was thinking more of the Fed than the ECB. In terms of inflation, I agree in part. High inflation isn't as apocalyptic as it is made out to be. Indeed, there are some good things about it:

1. Less wealthy households tend to have significantly higher debt to earnings and debt to asset ratios. This means that inflation, which erodes the value of their debt, can help with inequality (obviously a lot of other factors come into play).

2. High inflation isn't as huge issue so long as increases in wages keep up and inflation is predictable. Neither of these hold though; despite cries about a labor shortage, wage growth is not keeping up with inflation. Notably though, early on in this inflationary period, wage growth for the lowest earners was actually outpacing inflation by quite a bit, representing the largest real wage gains for low income workers in decades. This is no longer the case though, they are losing those gains.

That all said, because the massive amount of leverage employers have built up over the past several decades due to globalization and the ability to "off-shore" jobs, large increases in migration (and thus the supply of labor and demand for housing), and automation, I don't think wages are likely to keep pace with sustained high inflation.

Inflation also hurts retirees most, since they are likely reliant on pensions that are hurt by inflation and fixed income investments that lose value and real returns as inflation grows. Since the US electorate is dominated by older voters, this means there will be huge pressure to whip inflation.

So, my point isn't so much that inflation itself is the biggest issue facing the economy, it's that it is the most salient issue politically, and that here the interests of the wealthy and every one else diverges. Higher interest rates that reduce inflation might be the best policy for the bottom 90%, but it will be very detrimental to the price of equities, which are overwhelmingly held by the wealthy. I think this explains why responses to inflation remain fairly anemic despite public outcry over rising prices. And while inflation can be temporary, the effects of millions of Millennials buying their first homes during a period of 20-30% annual price increases in many markets can hurt growth for decades. -

The Ultimate Question of Metaphysics

Unfortunately, I can't offer a ton of clarification as I just discovered this myself looking for something totally different on nLab.

Some clarifying questions have been asked on Stack Exchange, and the answers are more accessible than the nLab articles. (E.g., https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/466638/what-was-the-lawveres-explanation-of-adjoint-functors-in-terms-of-hegelian-philo)

I am not particularly familiar with category theory so, while I get the Hegel references having read a good deal of Hegel and secondary sources, I get lost in the terminology pretty quickly here and have to keep looking stuff up. My math background is very much focused on applied mathematics. I've had a lot of experience with all sorts of regression techniques used in economics and polsci, game theory, a good deal of simulation work from my time working in intelligence, and a bunch of hybrid programming/stats skills I've developed since joining a startup that is trying to automate some of the work finance/management analysts do in local government/school districts. None of this is very abstract, so for a lot of topics in mathematics (e.g., set theory) I only have a hobbiest level understanding.

It's a shame these areas are not taught in the context of many fields though because I can see how they apply to a lot of work I do programming. For example, setting up a DAX measure to use as categories for a budget to actuals graphs is essentially using a lot of logical arguments to define a set. But I do it without formalism and sloppily in iterations until it works, and it doesn't even produce true definitions because no client's use their chart of accounts correctly.

More abstract mathematics, logic, and coding have a lot in common. I wish there was more cross pollination there. -

The Ultimate Question of Metaphysics

Very interesting post. Given your thoughts here , you might be interested in Lawvere's work on Hegel's dialectical using adjoint modalities if you haven't already heard of it.

https://ncatlab.org/nlab/show/Hegel%27s+%22Logic%22+as+Modal+Type+Theory

https://ncatlab.org/nlab/show/Aufhebung#lawveres_path_to_aufhebung -

Is there a progress in philosophy?

The difference between science and philosophy seems to be that science is a much greater complex of different investigative disciplines, and although there are changes of paradigm, in various ways within those disciplines, most of Science's progression seems to consists in building on the previous edifices of knowledge, and in shifts of focus, rather than in, so to speak, demolishing the whole building and reconstructing from scratch.

This is a good point. Most science is iterative. When there is a major paradigm shift (ala Kuhn) though, it tends to be that philosophy or mathematics is getting involved more directly in science. For example, two of the biggest "revolutions" across the sciences since the second half of the 20th century have been the emergence of chaos theory and information science. Both have shaken firmly held convictions in multiple fields about "the way things are" and remade prevailing paradigms. For a specific example, information science has dramatically changed how biologists define life and challenged the central dogma of genetics (i.e. that genes are the primary, perhaps only movers in evolution).

In those two examples, philosophy played some role, but it was the introduction of new mathematics, a way of mathematically defining information on the one hand, and new mathematics for defining complex dynamical systems, fractional dimensions, etc. on the other that really fueled the "revolutions." However, Einstein's revolution, the replacement of Newtonian absolute space and time with space-time, seems to have a lot more to do with challenging previously unanalyzed philosophical preconceptions.

I think it's fair to say that work in mathematics and philosophy differs quite a bit from science. It's interesting how, despite being so different, the disciplines can support each other so well, even science supporting math; as computers have gotten more powerful, experimental mathematics has become a thing. Also, how science can plug away with the same methods, safely ignoring most of what goes on in academic mathematics and philosophy, building knowledge, until some limit is hit or a paradigm begins to show serious weaknesses. Then the three get back together to build something new. -

The time lag argument for idealism

I have not only read Berkeley, but sat through lectures on him and read secondary sources on the Principles. My reading of paragraph 45 is fairly common.

You're also confusing what I'm saying. "Things do not exist outside their being perceived by minds," is most definitely Berkeley's point. I'm not sure why you're getting hung up on external versus internal here. I mentioned "external" (and independent) objects, because that's what naive realism posits as existing.

Perhaps look up the principal of charity? Perhaps consider that your interpretation of Berkeley might not be everyone's, and that anyone who disagrees with you is not necessarily misunderstanding. I also really don't get your objections in light of how Principals is written. It's quite obvious that Berkeley knows he is saying something that is unintuitive.

I think what might make more sense for your argument is to simply drop the claim that being unintuitive/violating appearances is a black mark against a theory. After all, that same standard says that the world being round, germs causing disease, the periodic table, and the theory that squares A and B in the image below are the same color, are all bad theories simply because they clash with immediate intuition and sensation.

-

The time lag argument for idealism

I did not claim that the external sensible world exists unpercieved, and nor does he.

Exactly, and that contradicts naive realism, i.e., the belief that the word does exist unperceived. That's my entire point. Take Berkley, he is advancing a novel argument about the way reality differs from people's naive conception of it. It's a fine argument. However, "if a theory about reality implies that a whole load of our appearances are actually false, then that's a black mark against that theory. It is evidence - default evidence - that the theory is false." seems to apply to Berkley here, no?

Not 'all' minds. Our minds. That is, those minds whose sensations represent the world they are sensations of to have outness. It appears external. He concludes that it is.

I assume there is a typo confusing me here, but I can't figure out what it is or what you're trying to say.

Have you actually read the principles or are those cherry picked quotes from a website?

Because if you actually read him he's very clear about this. Those quotes are taken out of context. Willfully. Read him and see.

I've read the Principles many times. What makes you think that? I've quoted the entire paragraphs in question.

He doesn't think your desk disappears when you stop perceiving it. He does think it can't exist unpercieved.

>The desk can't exist when it is unperceived.

>You are alone in your office.

>You get up and leave, shutting the door.

>Your desk is no longer being perceived; it thus does not exist.

Quibble with the use of the word "disappeared" if you want, but the logic here is that the desk ceases to exist when no one is perceiving it.

Arguably, Berkley is saved from this conclusion through God's perception of all that is, but notably he does not invoke that solution when he anticipates the argument about things like "disappearing desks."

He says:

...it will be objected that from the foregoing principles it follows things are every moment annihilated and created anew. - In answer to all which, I refer the reader to What has been said in sect 3, 4, &c, [sections that go over how things do not exist except as sensations] all I desire he will consider whether be means anything by the actual existence of an idea distinct from its being perceived.

Or to paraphrase: "a thing existing without being perceived is meaningless and incomprehensible, less so than that things might come into existence as they are perceived." -

"Stonks only go up!"

I think it owes to the field being necessarily more closely tied to politics than other fields.

I also think a huge black mark against economics comes from the mystification of Smith's "invisible hand," and the "power of markets."

We now know that these patterns of phenomena are what we call emergence and complexity. Economies are complex, dynamical systems. We have a lexicon and formalisms for defining and describing this complexity. Nevertheless, there is still a deep trend in economics to mistify markets, to see this complexity as something unique to markets, and thus intervention in markets as somehow "spoiling the market magic," instead of seeing that the economy will remain a dynamical system no matter how you set things up. Its dynamical nature just means policy interventions may have unintended consequences. -

The time lag argument for idealism

Berkeley doesn't think external objects exist when no one is perceiving them (naive realism). See the Principles:

I am content to put the whole upon this issue; if you can but conceive it possible for one extended moveable substance, or in general, for any one idea or any thing like an idea, to exist otherwise than in a mind perceiving it, I shall readily give up the cause…. But say you, surely there is nothing easier than to imagine trees, for instance, in a park, or books existing in a closet, and no body by to perceive them. I answer, you may so, there is no difficulty in it: but what is all this, I beseech you, more than framing in your mind certain ideas which you call books and trees, and at the same time omitting to frame the idea of any one that may perceive them? But do not you your self perceive or think of them all the while? This therefore is nothing to the purpose: it only shows you have the power of imagining or forming ideas in your mind; but it doth not shew that you can conceive it possible, the objects of your thought may exist without the mind: to make out this, it is necessary that you conceive them existing unconceived or unthought of, which is a manifest repugnancy. When we do our utmost to conceive the existence of external bodies, we are all the while only contemplating our own ideas. But the mind taking no notice of itself, is deluded to think it can and doth conceive bodies existing unthought of or without the mind; though at the same time they are apprehended by or exist in it self

His responds to the objection that his theory has it so that our office furniture disappears whenever we close the door to our offices, only to reappear when we open the door. He does not say, as you suggest, "no, you misunderstand, the office furniture exists the whole time (as in objective idealism)." He says, in so many words, "so what?"

Which is fine for his purposes, but definitely runs into the problem I highlighted above, where this does not jive with naive appearances.

45. Fourthly, it will be objected that from the foregoing principles it follows things are every moment annihilated and created anew. The objects of sense exist only when they are perceived; the trees therefore are in the garden, or the chairs in the parlour, no longer than while there is somebody by to perceive them. Upon shutting my eyes all the furniture in the room is reduced to nothing, and barely upon opening them it is again created – In answer to all which, I refer the reader to What has been said in sect 3, 4, &c, all I desire he will consider whether be means anything by the actual existence of an idea distinct from its being perceived. For my part, after the nicest inquiry I could make, I am not able to discover that anything else is meant by those words and I once more entreat the reader to sound his own thoughts, and not suffer himself to be imposed on by words. If he can conceive it possible either for his ideas or their archetypes to exist without being perceived, then I give up the cause; but if he cannot, he will acknowledge it is unreasonable for him to stand up in defence of he knows not what, and pretend to charge on me as an absurdity the not assenting to those propositions which at bottom have no meaning in them.

46. It will not be amiss to observe how far the received principles of philosophy are themselves chargeable with those pretended absurdities. It is thought strangely absurd that upon closing my eyelids all the visible objects around me should be reduced to nothing; and yet is not this what philosophers commonly acknowledge, when they agree on all hands that light and colours, which alone are the proper and immediate objects of sight, are mere sensations that exist no longer than they are perceived? Again, it may to some perhaps seem very incredible that things should be every moment creating, yet this very notion is commonly taught in the schools. For the Schoolmen, though they acknowledge the existence of matter, and that the whole mundane fabric is framed out of it, are nevertheless of opinion that it cannot subsist without the divine conservation, which by them is expounded to be a continual creation. -

The time lag argument for idealism

Really? What argument is that?

If a theory about reality implies that a whole load of our appearances are actually false, then that's a black mark against that theory. It is evidence - default evidence - that the theory is false.

The objects we experience appear to exist outside of us and independently of us. Idealism, at least in its subjectivist versions, says this common naive belief is wrong.

Incidentally, if there's no absolute present, there's no present.

Not what proponents of relativity are really arguing. Yes, there is no present, because there is no time. There is only space time.

Generally, the view of time taken vis-á-vis relativity is eternalist. That is, the past, present, and future all exist simultaneously. The illusion of a definite present is the result of how our bodies work, the terms themselves are arbitrary. See also: "the block universe," and "thermodynamic arrow of time."

You're saying your opponents are speaking nonsense and contradicting themselves, but if I'm following you correctly, this is because you are assuming a premise they don't accept is a given.

Obviously, even if there is an objective present there is still also a subjective sense of time. Anyone who has had to endure a road trip with a child aged 4-10 and has heard "are we there yet, we've been driving for days!" over, and over, can attest to this phenomena. -

Understanding the Law of IdentityI was thinking of this thread drawing fractions for my son. You can draw a half many different ways. A circle with a vertical line bisecting it and one side shaded, a circle with a horizontal line bisecting it and one half shaded, a circle with two lines and two 1/4th sections shaded that sit diagonal from each other, a circle chopped into 8ths making what looks like the nuclear waste symbol, etc.

None of these looks the same. Arguably, for almost all (maybe all) the systems we experience in everyday life, they actually are not the same. No pie is the same all the way through. No system is set up so that the distribution of molecules and the energy of individual molecules is evenly distributed throughout. Getting one slice of pie that is the size of half a pie is different from getting four slices that add up to half the area of the pie.

Got me thinking about how much of what we can do in the sciences is the results of being able to abstract away differences. This thread didn't go anywhere but it brings me back to the idea of synonymity. If things only exist as they exist for other things (e.g., information theoretic approaches) than you have a shifting amount of synonymity between different identities. Water = H20 = identity for many reactions. However, push enough water in one direction and tiny differences in energy levels result in (as of today's physics) totally unpredictable and chaotic turbulence. You move from differences that don't make a difference, to differences that make a large, macroscopic difference. -

The time lag argument for idealism

I read the OP. It just seems like a very similar argument could be made where materialism comes out on top under a quite similar yardstick.

The other issue you may want to consider is why so many other idealists have dropped absolute time. I haven't come across any post-relativity idealists who deny the theory of relativity and who demand an absolute present. You might be able to deal with the observations that led to relativity without ditching absolute time, but it will lead to non-absolute distances, with lengths stretching or shrinking for different observers. In general, I suppose this seems more problematic than opting for a subjective present. Also, even when you get past relativity, you still need to explain all the empirical evidence for the subjectivity of time from psychology.

Contemporary physicslism has ditched absolute time. You're taking absolute time as a given and saying the fact that physicalism has ditched absolute time, when it is a given, is a point against it. I'm not sure how this isn't begging the question.

Is an ontology that claims the world isn't flat also necessarily weaker because our senses tell us the world is flat? But then isn't it empiricism, data from our senses, that also told us that time is relative and that the world is round? Which data from the senses are being violated then? The reason space-time was accepted as a new paradigm was because it explained both the old way we saw things and new observations that didn't fit the old paradigm. One of the best arguments in favor of idealism is that so much of what we know, perhaps all of it, comes from the world of first person experience, but here you seem to be privileging naive conceptualizations based on those senses over models that cohere with more of our observations.

Space-time itself is a creaky, wounded paradigm, so I don't know if I'd accept it as the final word in any case, more of a predictive placeholder.

I don't think idealism necessarily has a harder time explaining these things, but it seems like it would if it kept hold of absolute time.

Just as an example of how this can work: even Hegel's pre-relativity idealism would have the present as the event horizon of the past, the line of continual becoming. In the sense certainty of the absolute present there is only abstraction, and so really contentless nothing. This isn't absolute, it's a contradictory period from which we get the emergence of lived experience. -

The time lag argument for idealism

If a theory about reality implies that a whole load of our appearances are actually false, then that's a black mark against that theory. It is evidence - default evidence - that the theory is false.

This is a bit of a strange way to try to justify idealism. I don't know of a single ancient creation mythos that appears to represent any sort of idealist ontology. "Naive realism," is "naive," because its how most, if not all the world thought about things at first. "The things I see are not me and exist outside me," is quite intuitive, hence seeing it as a core concept everywhere in history.

To be sure, idealism also pops up very frequently in history, but in every case I am aware of it emerges as a rebuttal to naive realism, not as the primary ontology.

I can see the claim that idealism is more parsimonious than physicslism, or that it has fewer explanatory gaps, but that it's more intuitive/follows more from appearances? Then why are gods in all the creation stories making the world out of mud, fire, etc.? -

Understanding the Law of Identity

This is a good post overall, but the bit about Hegel needs an addendum.

The law of identity may be denied, as I believe Hegel did. But doing this renders the other laws of logic, noncontradiction, and excluded middle, as useless. This is because these laws put restrictions on what we can truthfully say about a thing, by determining what is impossible for us to truthfully say about a thing.

For Hegel, the real is the rational. He's all about trying to walk his readers off the ledge of radical skepticism. Part of the way forward from doubting everything is to accept that the world is rational, not illogical. Because if the world isn't rational, then nothing necessarily follows from anything else, and knowledge becomes impossible.

Hegel definitely wants to keep rationality at the center of his thought. In his early theological writings he sees Logos, unifying reason (identified with Christ in The Gospel of John), as the element in faith that can lift man up and give him freedom.

Hegel's problem with identity as it is commonly formulated comes from his attempt to rebuild logic. He wants to create a logic that is aware of the self as thinking subject, and of objects as existing for that subject. He wants to move past propositions such as, "the apple is red," that take the apple and its redness as existing outside of the perceiving mind. Identity has to be different because identity changes and grows more complete over time as our knowledge grows (as the dialectical progresses). And he doesn't want to look just at the apple as being a part of an individual subject's mind, since he is not a solipsist or subjective idealist, but how it is for all minds.

Thus, the apple's identity can unfold through the progression of history. The truth of the apple is the whole, and so covers the apple as well as the apple seed, the sprout from that seed, the apple sapling that comes from the sprout, the branch that comes off the sapling-turned-tree, the bud on that branch, and the apple that springs from the bud, complete with new seeds. A = A can't fit the truth. Is the seed the tree, the United States in 1795 the United States in 2025? Since the truth of a thing is the process of its becoming the law of identity as commonly used becomes defunct, but it isn't just tossed aside. -

"Stonks only go up!"

To be fair, no one asks a biologist to predict the next mammal that will evolve, or a neuroscientist to guess what they're thinking of using neuroimaging alone. People's expectations for economists are strangely high. -

"Stonks only go up!"

I think any attempt to predict the particulars of a recession is a fool's errand. I'm talking more about how "what has been the case," is erroneously seen as "what must be the case in the future."

So, my point would be merely that there is no reason that a broad investment in large firms is going to necessarily result in robust returns. This is the experience of the Baby Boomers during their peak earning years, but this phenomena seems more driven by government intervention than is commonly admitted.

I think people shouldn't be led to think of their retirement savings as being something that is going to "grow" over time. Equities are by no means guaranteed to grow at a rate greater than inflation. A glance at the historical yields on investment grade bonds vs inflation suggests that savings will have a hard time keeping the value they held when you put the money away, let alone gaining value.

The easiest way to think about this is just to ignore inflation entirely. If you want to be able to pull $40,000 a year out of a retirement account from age 65-85, you might want to expect that you have to put $20,000 in a year from age 25-65 (holding all $ amounts constant).

But that's definitely not what you're told in the US. You're told to expect that money put into stocks will result in real growth, significantly above inflation, over the course of your life.

I'd say the interesting questions here are:

1. Why have such huge blinders developed, such that professionals don't look back beyond around 1990, or to other developed markets and see that "stonks" in fact, do not always see their prices go up?

2. Why would otherwise well informed people even expect the value of large corporations' stock to routinely grow faster than GDP for decades on end?

3. To what degree has the surge in stock prices been due to government/central bank interventions (targeting stock prices or not; in general they are targeting unemployment rates)? I get the sense that the large population of "long term unemployed" people created by globalization was used as an excuse to keep interest rates low under the guise of helping boost employment, when really a key benefit was inflating asset values. After all, labor force participation rates never came close to returning to pre-2008 levels even as we saw "historically low unemployment," circa 2019, but interest rates were kept low because small hikes caused the stock market to tank.

4. Ethically, should we have a better way of helping people fund their retirement? The current system seems like a perfect storm of perverse incentives where politicians are now motivated to make sure stock prices keep going up because people have been talked into betting their ability to retire on the fact that they WILL go up.

This is incidentally not that different from another mantra for developed economies: "housing values always go up." Apparently they can keep increasing at a rate higher than wages, and in the face of declining birth rates and eventually declining populations... -

Consciousness, microtubules and the physics of the brain.

Maybe. I recall and experiment a few years back where entire photosynthetic bacteria were said to be entangled with one another.

This shouldn't be shocking. It would be shocking if life didn't involve and take advantage of quantum behavior, given that life is made up of quantum scale objects. The fact that any theory of "quantum behavior in living systems," was initially written off simply showcases how people's philosophical/ontological commitments cause them to ignore the data sitting in front of their faces. The hard dividing line between classical and quantum worlds never made any sense to begin with.

That said, I have no idea how quantum behavior in brains is supposed to solve the hard problem or act as some sort of explanatory panacea. It seems to me like identifying more quantum behavior within our bodies will just make explanations of biology even more complicated and harder to parse. There is definitely a "God of the gaps" narrative surrounding QM vis-a-vis the hard problem and I think that is also a misunderstanding of what it means for quantum behavior to be involved in the brain. -

Consciousness, microtubules and the physics of the brain.

The Great Courses' Mind-Body Philosophy is great. They got Patrick Grim to do it. His "Mind and Consciousness: Five Questions," which has work from Chalmers, Dennett, Putnam, L.R. Baker, Hofstadter, and others could be a nice supplement.

The courses are significantly cheaper through Amazon/Audible than on the Great Courses site BTW.

I think the Penrose-Hameroff Orch-Or theory as initially proposed was regarded as implausible because the brain is too hot and wet for molecular superpositions exceeding more than a dozen or so atoms, even in microtubules.