-

counterpunch

1.6k

counterpunch

1.6k

So, innate? — bongo fury

There is no necessary relationship between signifier and signified. The word for the thing, signifier, is not the thing itself, signified. Red is a thing; a particular wavelength of light that excites particular cone shaped nerve endings in the eye. We might have used another word for it, but that wouldn't make it a different thing. Experience of the thing that we call red, is the same for you and for me - unless you're colour blind, which about 10% of men are. Women, less so. In summary, I'm on the universalist side of the debate - and my 'cut the red wire' joke was intended to mock the Worfian cultural relativists. -

bongo fury

1.8kInnately. If you and I are looking at a chair, are there two chairs? One for each of us? — frank

bongo fury

1.8kInnately. If you and I are looking at a chair, are there two chairs? One for each of us? — frank

Why then innately, though? Especially if you are likening colour classification to furniture classification?

:cool: -

frank

18.9kWhy then innately, though? Especially if you are likening colour classification to furniture classification? — bongo fury

frank

18.9kWhy then innately, though? Especially if you are likening colour classification to furniture classification? — bongo fury

Sorry, I wasn't likening them. I'm just guessing that redness is hardwired. As I said, the memory of seeing red probably depends on language use.

The chair was a different question. -

bongo fury

1.8kThere is no necessary relationship between signifier and signified. The word for the thing, is not the thing itself. — counterpunch

bongo fury

1.8kThere is no necessary relationship between signifier and signified. The word for the thing, is not the thing itself. — counterpunch

Yep, yep.

Red is a thing; a particular wavelength of light that excites particular cone shaped nerve endings in the eye. — counterpunch

Ok... or: it's a class of illumination events (stimuli) that cause that kind of excitation.

Experience of the thing that we call red, is the same for you and for me - unless you're colour blind, — counterpunch

Here's where I'm guessing your lack of nuance on this issue (that of the OP) is connected with a naive belief in internal sensations (qualia). I suspect the two problems can be treated together.

Clearly, I'm on the universalist side of the debate - and my joke was intended to mock the Worfian cultural relativists. — counterpunch

Yes, I was just checking that was your drift.

Thanks all :cool: bye for now -

Razorback kitten

117You hear people say things like "is my red the same as your red?" but you don't so often here someone asking if their sense of the smell of a banana is the same as your sense of it. Or if you hear the sound the same way. Because vision is a slightly more, personal feeling, sense.

Razorback kitten

117You hear people say things like "is my red the same as your red?" but you don't so often here someone asking if their sense of the smell of a banana is the same as your sense of it. Or if you hear the sound the same way. Because vision is a slightly more, personal feeling, sense. -

counterpunch

1.6kHere's where I'm guessing your lack of nuance on this issue (that of the OP) is connected with a naive belief in internal sensations (qualia). I suspect the two problems can be treated together. — bongo fury

counterpunch

1.6kHere's where I'm guessing your lack of nuance on this issue (that of the OP) is connected with a naive belief in internal sensations (qualia). I suspect the two problems can be treated together. — bongo fury

It's not a lack of nuance - it's a view that's informed by the evolutionary development of the organism in relation to a causal reality with definite characteristics, where the organism has to be 'correct' to reality to survive. It's also based on consideration of things like art, discussion of art, traffic lights and colour coded electrical wires - all of which suggest that "red" is an objective reality, experienced similarly by physiologically similar individuals.

I may not use big words. I avoid hippy dippy terms like qualia - like the bubonic plague they are, but don't presume that, because I seek to express myself in the simplest possible terms, that I don't know what those terms mean, and haven't fed such considerations into my conclusions.

Thanks all :cool: bye for now — bongo fury

Run Forrest, run! -

Fooloso4

6.2kIn front of you, or inside you? — bongo fury

Fooloso4

6.2kIn front of you, or inside you? — bongo fury

This presupposes a problematic representational theory of perception. I do not see two things - the thing in front of me and the thing in my mind.

The other things it is (colour-wise) like? — bongo fury

Suppose something happened to me when I was very young and my perception of color was altered. What I previously saw as red I now see as green. This happened long enough ago when I was young enough not to remember it happening. But I was thought to call this "green" sample in front of me "red". Although I see it differently than you do, there is no way for either of us to know that. -

ernest meyer

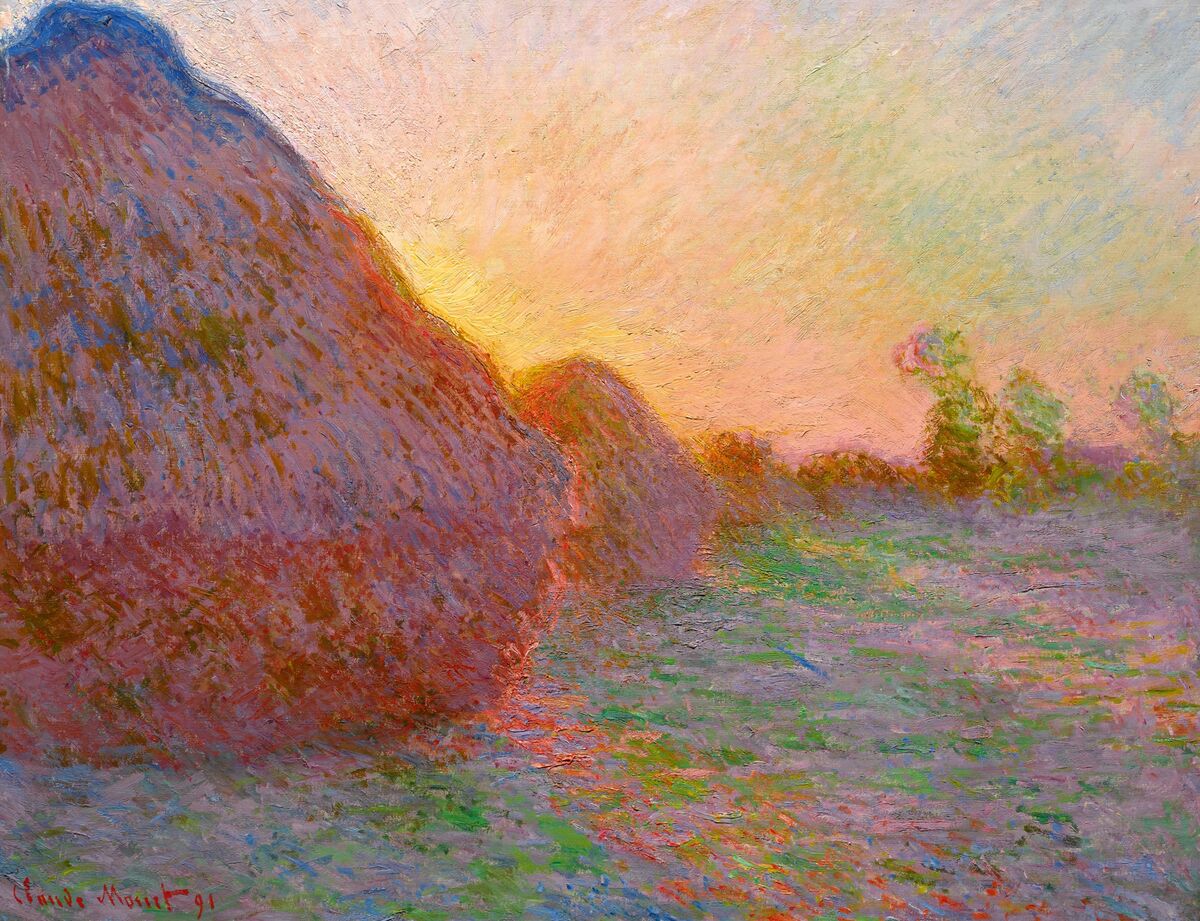

100HAYSTACKS AT SUNSET - MONET

ernest meyer

100HAYSTACKS AT SUNSET - MONET

Some of the last thoughts by the metaphysical logician Wittgenstein were on the mystical nature of color. He asked the question whether color was imbued in physical substance, or an artifact of our perception, to which he felt there was no final answer. In his earlier thought, that would have been all that could be said. But in his later thought, the discussion of color becomes meaningful when we wield the concept like a tool.

While many have scoffed at the ridiculousness of considering something like color in so much depth, consumerism has indubitably transformed color into a commercial tool. One may only witness the incredible number of packages and brands distributing lipstick and eye makeup colors at the entrance of any local pharmacy, where once there were medicines and common household goods.

This proliferation of 'color for sale' inside the caverns of our stock houses replaces appreciation of the natural colors around us, and their sensitive purpose. Primary in this spectrum is the color of the chloroplast's photosynthetic mechanism. We are attuned to see this vivid green most of all, because that mechanism is how plants create and sustain all life on the surface of this planet. The hues around the green of growth are therefore most frequently easiest for eyes to see, and therefore dominated by peculiar evolutionary developments, such as flowers and fruits to attract animal life and encourage it, in the most bizarre forms of symbiosis, to propagate the seed of the sedentary plant. Yet no one complains of this massive act of domination, but instead considers it only with pleasure, for all the benefits that the plant provides to animal and human experience.

From this each culture has attached its own secondary associations. For example, in the West, scarlet is associated with danger, and forbidding of action; whereas in the East, scarlet is the color of parties and festivities, across cultural, familial, and political realms.

The subtlety of Wittgenstein's thought was to identify that association as being arbitrary, or rather, without logical necessity, yet still existent and powerful enough to be a causal agent. We are influenced by color, both by deep evolutionary forces, and by abstract cultural associations; yet the colors themselves possess no intrinsic properties to cause such influence. The colors themselves are no more than labels we apply to a physical phenomena (parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, in this case). When engaged in tantric meditation, we are encouraged to perceive beyond the direct physical manifestation, and to discover the strange and illogical passions to which such phenomena can bend our unconscious will. To the insights from such introspection the tantric gurus attach the names of Gods and forces to which they claim direct and irrefutable knowledge. It is the path of Wisdom to pass by such exaggerations without verbal debate; for if some person becomes convinced of a supernatural connection at the borders of perception, there is no verbal dissuasion possible from the delusion.

The irresolvable question to Wittgenstein nonetheless remained: we have the capacity to consider the nature of experiencing a color, such as the paradoxical nature of scarlet, without connection to any physical object directly, but merely as a property of itself.

The word 'merely' is in this case no diminishment, but rather remarkably, in some ultimately unknowable absolute sense, a humble portal to a deeper understanding of conceptual reality. In some respects, our understanding must always be limited, for, how much can we truly appreciate the different associations of any particular color to different cultures?

It even remains perplexing to those who share in communal joy, for example, this picture of haystacks by Claude Monet, even while others pass it by in disdain and scornful abjuration of those who find peaceful appreciation within it.

For any introspective insight we obtain, no matter how wise it may be to ourselves, remains only for ourselves, if we find no way to apply that insight for the omniversal influence of society.

From our insights we may choose sides, and argue for example that such concepts as color could exist without any contemplation of such concepts by any thinking being. If so, we may pause to consider what concepts remain yet to be considered. For if there exist concepts by themselves, not in the thoughts of any conscious entity, then there might remain concepts of reality as yet unknown by any person at all.

If you look again at Monet's painting, perhaps now the striking scarlets in the haystack appear in new shades of our imagination. In the distant hazy cottages we may infer, from this color, the joyful and industrious party of farmers embarked on celebration of their haymaking. We may infer, from this color, the warmth inside the haystack itself, lingering more slowly inside the straw bundles, during the twilights of sunset. Others may share the imagination and inference of Monet's intent. But within Monet's own silence, we find no confirmation of our speculation, and our insights persist only as hypothetical inferences of his intent. Those who claim some perfect understanding of reality may have deep contributions to make on its underlaying precepts, but for most of our knowledge of others' experience, the veil of postulation is too impenetrable to remove the bias of personal perspective.

We may also choose to believe there are no abstractions beyond those conceived by conscious entities. Leibniz argues that we see imperfectly that which is totally and perfectly understood by God, from which our own abilities of understanding and imagination propagate. Modern thinkers prefer to remove more majestic conceptions with Occam's razor, diminishing us further into the effervescent randomness of physical events.

Yet no matter how much the nihilists and cynics scoff, too many are struck by the beauty of material order and fantastic structures of rational thought, leading to mathematics and the physical sciences. Too many find something more in such as a painting by Monet; a sense of wonder, undeniable in strength, somehow demanding finer resolution of our own understanding, within the passing of days, and seasons, and eras of our civilizations. -

Manuel

4.4k

Manuel

4.4k -

magritte

593belief in mental furniture. Contra Witty, of course. Also, more salient for me, Goodman. — bongo fury

magritte

593belief in mental furniture. Contra Witty, of course. Also, more salient for me, Goodman. — bongo fury

Mental furniture that would present us with mental objects has major drawbacks. The mind, like the outside world, is a complex chaotically functioning place out of where rational thought is only a small presentational fragment.

While the outside world is third person accessible and open to public observation and survey, the mind is private and we have no-one else to ask whether a feeling, sensation, motive, or attitude is really there at all rather than being a momentary illusion. We cannot directly see into our minds without some intermediary higher level conceptual modeling.

When I talk to the doctor over the phone complaining of sporadic leg pain, I have trouble relating that general sensation in words specific enough for diagnostic needs. Even at the office, the doctor must poke and prod for a couple of minutes until the problem is narrowed to the right strained ligament. Why is that? Isn't much of experience unavoidably social, conducted primarily through language?

BTW, aren't both Witt and Goodman attempting to solve the same problem of what can be said? Reformulating philosophy might not be enough to fill the gap between the mind and the word. -

ghostlycutter

67Not necessarily, but probably, unless my inner-feelings, mementos and dimension differs from yours. If so and I differ, the red I see may be your green.

ghostlycutter

67Not necessarily, but probably, unless my inner-feelings, mementos and dimension differs from yours. If so and I differ, the red I see may be your green.

I would however suggest that the colours you see aren't different but are in different order.

The blue I see reminds me of waves and birds; if you were to describe your blue using mementos, how would you? -

bongo fury

1.8kYou hear people say things like "is my red the same as your red?" but you don't so often hear someone asking if their sense of the smell of a banana is the same as your sense of it. Or if you hear the sound the same way. — Razorback kitten

bongo fury

1.8kYou hear people say things like "is my red the same as your red?" but you don't so often hear someone asking if their sense of the smell of a banana is the same as your sense of it. Or if you hear the sound the same way. — Razorback kitten

Not so often, no. But expecting a parallel situation in the different modalities is common enough in theoretical talk.

By "lack of nuance" I meant no disrespect guvnor, honest. Only, that

that "red" is an objective reality, experienced similarly by physiologically similar individuals. — counterpunch

seems to assume without question a rainbow of internal, private sensations. Whereas even the universalist side of the linguistic debate (on the wiki page) considers the aspect of public negotiatiation (linguistic evolution), and an external subject-matter.

Pleased to hear more detail of your theory, whatever the terminology.

This presupposes a problematic representational theory of perception. I do not see two things - the thing in front of me and the thing in my mind — Fooloso4

Well, quite. The what thing in your what?

Although I see it differently than you do, there is no way for either of us to know that. — Fooloso4

Is this the beetle story?

Are our beetles innate?

You are definitely addressing innateness... possibly that of the semantics of red, rather than of the syntactic identity of red. Will get back to this.

the same problem of what can be said? — magritte

Or can't because it's private, then? Not sure of your drift. (Tractatus?)

Was I anywhere close, here:

On the other hand, that may have been what magritte meant, too. "Innate" as in, our agreement as to the external extension happening to result from a corresponding agreement as to the internal extension. — bongo fury

? By internal extension I mean the range or class of internal sensations (images, qualia) referred to (on an internalist reading) by "red".

unless my inner-feelings, mementos and dimension differs from yours. If so and I differ, the red I see may be your green.

... The blue I see reminds me of waves and birds; if you were to describe your blue using mementos, how would you? — ghostlycutter

That's intriguing, because it isn't necessarily the usual beetle-swapping story, even though your other remark suggests it might be, for you:

I would however suggest that the colours you see aren't different but are in different order. — ghostlycutter

But, yeah... will get back to this, too. Thanks all. -

Fooloso4

6.2kThe what thing in your what? — bongo fury

Fooloso4

6.2kThe what thing in your what? — bongo fury

I was responding to your question:

In front of you, or inside you? — bongo fury

Is this the beetle story? — bongo fury

I don't think it is helpful to introduce one problem as the solution to another.

It is clear that you do not see that and why my original response was a philosophical joke. -

Joshs

6.7k

Joshs

6.7k

We are influenced by color, both by deep evolutionary forces, and by abstract cultural associations; yet the colors themselves possess no intrinsic properties to cause such influence. The colors themselves are no more than labels we apply to a physical phenomena (parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, in this case). — ernest meyer

Colors are not physical phenomena, they are perceptual phenomena, and as such are the achievement of a constructive process. They are intentional acts , and like all acts, they produce a change of sense. Colors may not present ‘intrinsic’ properties on the order of qualia, but they do present us with the experience of a transformative construction. For instance, the perceptual act of color constitution is created primoridally as a black shape either emerging out of or receding into a dark background. You can demonstrate this yourself. Cut out a white cardboard circle, paint one half black , and then draw a series of black lines following the curvature of the circle on either side of the disk emerging from the black half. Then attach it to a fan and watch the appearance of red and blue.

This explains why red is often a metaphor for anger and aggression, and blue can represent calm and coldness.

Red is literally the sense of a shape popping out at us and blue is an appearance receding from us( and the other colors of the rainbow fit between these two

poles), even as these are just features of a motionless surface.

So our language, through its metaphors , is in fact indicating organizational characteristics ( aggressive approach vs passive receding) of the supposedly ‘private’ feel of color.

Color, like all other perceptions, is never just immediate ‘sense data’ taken from the world , but correlations , figures emerging out of and co-created by their relationship to a background bodily field. And one can see how perceptual correlations are intertwined at a higher level with the social field of interpersonal relations. -

ernest meyer

100This explains why red is often a metaphor for anger and aggression, and blue can represent calm and coldness. — Joshs

ernest meyer

100This explains why red is often a metaphor for anger and aggression, and blue can represent calm and coldness. — Joshs

that is AN explanation. One of many. lol. Let me think about it, thanks for the thoughts. -

RogueAI

3.5kIf we tested two identical brains seeing red and the brain states were identical, we could infer the experience of seeing red is identical, but we could never verify it. A person could always say, "yeah, but brain A is occupying point X and brain B is occupying point Y, so maybe brain A's experience of red is different than brain B's." How would you prove or disprove that? That's the thing about consciousness: it's only measurable in ourselves. For all I know, you're a bunch of zombies or simulated people. No amount of brain scans or neural correlates can convince me other people are conscious. We just assume it's true because solipsism is kind of horrifying and depressing, at first.

RogueAI

3.5kIf we tested two identical brains seeing red and the brain states were identical, we could infer the experience of seeing red is identical, but we could never verify it. A person could always say, "yeah, but brain A is occupying point X and brain B is occupying point Y, so maybe brain A's experience of red is different than brain B's." How would you prove or disprove that? That's the thing about consciousness: it's only measurable in ourselves. For all I know, you're a bunch of zombies or simulated people. No amount of brain scans or neural correlates can convince me other people are conscious. We just assume it's true because solipsism is kind of horrifying and depressing, at first. -

frank

18.9kSuppose something happened to me when I was very young and my perception of color was altered. What I previously saw as red I now see as green. This happened long enough ago when I was young enough not to remember it happening. But I was thought to call this "green" sample in front of me "red". Although I see it differently than you do, there is no way for either of us to know that. — Fooloso4

frank

18.9kSuppose something happened to me when I was very young and my perception of color was altered. What I previously saw as red I now see as green. This happened long enough ago when I was young enough not to remember it happening. But I was thought to call this "green" sample in front of me "red". Although I see it differently than you do, there is no way for either of us to know that. — Fooloso4

Maybe in the future there will be mind-o-vision technology so we can put your experience up on a monitor and tell when this sort of thing is happening.

Would that change your philosophical outlook? -

Joshs

6.7kTreating these as if they were mutually exclusive will get you nowhere. — Banno

Joshs

6.7kTreating these as if they were mutually exclusive will get you nowhere. — Banno

I did not mean to suggest that they are mutually exclusive. What I meant was, following Husserl and Merleau-Pontus, the ‘physical’ is a higher order derived product of constitution, and can’t be used to ‘explain’ the fundamental basis of color in perception. . -

frank

18.9kThe topic of "the physical" is very problematic. Why assume that mind is not a wholly physical phenomena? One would have to show why physical stuff leaves no room for mind. — Manuel

frank

18.9kThe topic of "the physical" is very problematic. Why assume that mind is not a wholly physical phenomena? One would have to show why physical stuff leaves no room for mind. — Manuel

Strictly speaking, if you want to assert that mind is physical, you need to explain mind. Your audience doesn't need to show anything.

I saw an article suggesting that mind might be some sort of electromagnetic shenanigans. At one time, electromagnetism wouldn't have qualified as physical.

As long as you say physicality is a category that's in flux, but always basic to everything, you can call mind physical. That's not saying much, though. -

Banno

30.6kPhenomenology sees them as derivative abstractions. — Joshs

Banno

30.6kPhenomenology sees them as derivative abstractions. — Joshs

So much the worse for phenomenology, then. It leads to things such as:

Colors are not physical phenomena... — Joshs

...as if colour could not be measured, mastered and mathematicised; and

...they are perceptual phenomena, — Joshs

...as if you and I did not overwhelmingly agree as to what is black and what is white.

Phenomenology starts in the wrong place and proceeds in the wrong direction. -

Manuel

4.4k

Manuel

4.4k

That is correct. I won't be saying much. But there's already so much stuff about "physical" as opposed to mental or opposed to consciousness, that this little bit, is already something. Particularly when strands of physicalism claim that our experience is an illusion, not real.

I don't see why I need to explain mind, in order to say that mind is physical.

I've been quoting this a bit too much recently, but I think it's worth it one more time:

"It is said that we can have no conception how sensation or thought can arise from matter, they being things so very different from it, and bearing no sort of resemblance to anything like figure or motion; which is all that can result from any modification of matter, or any operation upon it.…this is an argument which derives all its force from our ignorance. Different as are the properties of sensation and thought, from such as are usually ascribed to matter, they may, nevertheless, inhere in the same substance, unless we can shew them to be absolutely incompatible with one another.”... this argument, from our not being able to conceive how a thing can be, equally affects the immaterial system: for we have no more conception how the powers of sensation and thought can inhere in an immaterial, than in a material substance..."

(Italics mine)

"...there [is] in matter a capacity for affections as subtle and complex as any thing that we can affirm concerning those that have hitherto been called mental affections."

- Joseph Priestley "Disquisitions Relating to Matter and Spirit" -

Fooloso4

6.2k

Fooloso4

6.2k

I have not presented a philosophical outlook. My comments were intended to point to the problem faced in asking the question. It you are asking whether your mind-o-vision would provide a clear answer to the question, perhaps; although there may still be problems with the identify of brain-states and subjective experience.

There is general agreement about the frequency range on the light spectrum for red. If we can identify specific areas of the brain that light up when we see specific colors, I assume, given our biological make-up that they would be the same. But if my perception of color had been altered as in the example then the area of my brain that lit up would be the area associated with green. Practically speaking though, this would not be a problem. I would still be able to identify colors and call them what everyone else does. -

Joshs

6.7k

Joshs

6.7k

as if you and I did not overwhelmingly agree as to what is black and what is white.

Phenomenology starts in the wrong place and proceeds in the wrong direction. — Banno

Then so does Wittgenstein.

Look. My sense of what a color is changes in subtle ways in relation to my own previous perception of it all the time , in response to changing contexts of experience , both social-linguistic and private. If I am an artist, the meaning for me of red may be extraordinarily differentiated , and change in all kinds of ways as a result of different projects I engage in. I am constant evaluating and attempting to validate

my precious understanding of the sense of all of my perceptions, so my own use of words for color and sound and touch that I use for my own purposes shifts subtly all the time.

In similar fashion, the words we share with others for color undergo all kinds of changes in sense, both those that members of a group agree on and those they don’t. Straws on babbles on about evolutionary and genetic determinants of color perception, but what matters for

the social consensus concerning the meaning of a color word is what sense of color is being meant and how we go about validating whether others are meaning a similar sense not. So for instance ,the word red can be used to pick out an object against a background.

For this task it is irrelevant whether my perceived red is the same as yours. All that matters is that we both consistently pick out the same object. Then there can be an aesthetic use of the word red. If my red is fiery hot, aggressive, angry and yours is the opposite, then the word red in this context isn’t very useful in capturing a shared understanding.

Strawson’s reminder that we may be meaning different things with the use of the same color word is sort of beside the point. First of all, how would we even know this unless we established some situation

to validate it? If we normally don’t force our shared use of words like red to undergo validation its because our pragmatic involvement with it doesn’t present difficulties. The word is doing what we need it to do.

If it came to be that an important shared understanding of a word sense began to unravel, that is, if it became apparent that each user of the word could no longer depend on other users to behave in previously anticipated ways in response to the use of the word, the. it would likely cease to be practical in its present form. -

RogueAI

3.5kThe topic of "the physical" is very problematic. Why assume that mind is not a wholly physical phenomena? One would have to show why physical stuff leaves no room for mind.

RogueAI

3.5kThe topic of "the physical" is very problematic. Why assume that mind is not a wholly physical phenomena? One would have to show why physical stuff leaves no room for mind.

I don't see good reasons to assume otherwise.

Aside from the various "how much does your mind weigh?" objections, let me give you my favorite argument:

If brains and minds are the same thing, then necessarily, if two people are talking about their minds, they're talking about their brains (and vice-versa). Ancient peoples were able to meaningfully talk about their minds and mental states, however, ancient peoples had no idea how the brain worked. The Greeks thought it cooled the blood. If brains and minds are the same thing, it follows that those ancient peoples who were meaningfully talking about their minds and mental states were also meaningfully talking about their brains and brain states, which is an absurdity. -

Manuel

4.4kIf brains and minds are the same thing, then necessarily, if two people are talking about their minds, they're talking about their brains (and vice-versa). Ancient peoples were able to meaningfully talk about their minds and mental states, however, ancient peoples had no idea how the brain worked. The Greeks thought it cooled the blood. If brains and minds are the same thing, it follows that those ancient peoples who were meaningfully talking about their minds and mental states were also meaningfully talking about their brains and brain states, which is an absurdity. — RogueAI

Manuel

4.4kIf brains and minds are the same thing, then necessarily, if two people are talking about their minds, they're talking about their brains (and vice-versa). Ancient peoples were able to meaningfully talk about their minds and mental states, however, ancient peoples had no idea how the brain worked. The Greeks thought it cooled the blood. If brains and minds are the same thing, it follows that those ancient peoples who were meaningfully talking about their minds and mental states were also meaningfully talking about their brains and brain states, which is an absurdity. — RogueAI

I entirely agree with that. We don't have the capacity to explain mind with neuroscience. How do I link a post of mine? I explain this in detail, I believe.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum