-

Mikie

7.4kI don't care how much profit companies make. how much executives are paid, or how it is determined as long as workers are paid a decent living wage. — T Clark

Mikie

7.4kI don't care how much profit companies make. how much executives are paid, or how it is determined as long as workers are paid a decent living wage. — T Clark

That's not quite the topic. Regardless, to pursue it: workers aren't being paid a decent wage, in reality. And the reason they're not is partly determined by these OP questions -- namely, how profits are distributed and who makes the decisions. The decisions certainly aren't being made by workers.

But let's assume they are being paid a decent wage. They get enough to eat and live and have healthcare. Is that it? They deserve only that? What if they're the ones doing the lion's share of the work? Don't they deserve more than simply a "decent living wage"?

I would suggest they deserve some say in the decision making, regardless of material conditions. -

PhilosophyRunner

302I don't understand your objection to "the market". An analogy - I say the electorate selected Biden as president. You say the electorate had nothing to do with it, it was real people. Of course it was real people, and the collection of people who did the voting within the system, I am referring to as the electorate. Both are correct. The electorate voted for Biden, and the electorate is real people making real decisions, not a magical beast.

PhilosophyRunner

302I don't understand your objection to "the market". An analogy - I say the electorate selected Biden as president. You say the electorate had nothing to do with it, it was real people. Of course it was real people, and the collection of people who did the voting within the system, I am referring to as the electorate. Both are correct. The electorate voted for Biden, and the electorate is real people making real decisions, not a magical beast.

Anyway I will give an example of where "the market" explicitly influenced decisions. This happened in the U.K.

A company decided to pay all of their staff the same amount - £36,000. This included software developers and clerical workers.

What happened? They struggled to hire software developers because other companies were willing to pay a lot more for this job (i.e they were paying below market value for the job - but I will only use the word in brackets for you). Equally they were inundated and overwhelmed with applications for clerical jobs because other companies were paying a lot less (i.e they were paying above market value for the job).

Ultimately they had a very disgruntled and unhappy workforce with a lot of internal conflict, and gave up and mostly likely ended up paying a similar wage to their competitors for each job (market rate for the job).

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-55800730 -

javi2541997

7.3kIn real life, does it play out like this? Who decides? I'm talking of course about business, particularly big business. — Mikie

javi2541997

7.3kIn real life, does it play out like this? Who decides? I'm talking of course about business, particularly big business. — Mikie

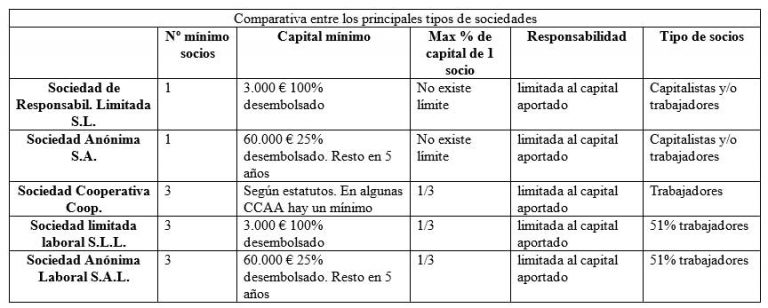

Yes, I know some examples in real life. When you want to start up a business, you need to distribute everything in proportions. According to the law, presumably each participant owns the same part or proportion. Nonetheless, there are exceptions to the rule and it could exist the scenario where a participant holds more proportion than the rest.

But we have a dilemma here. If we let one participant to hold 51 % of the overall, he/she could do or manage whatever without the consideration of the rest of the members. To avoid this situation of abuse, the law offers some rules.

I. Acts that necessarily need 3/4 of the votes of the participants. You will need a lot of votes, doesn't matter all the proportion you hold. For example: removing an administrator due to his unfair administration.

II. Acts who need absolute wholesale. For example: Assign credits or invest in the stock market.

Thanks to the voting system and limiting the proportions among the members, we would have a democratic membership or entrepreneur.

For example:

Hmm. A voting system within a company, you mean? — Mikie

Exactly. They owners vote in a General Meeting -

PhilosophyRunner

302Now to say what I think should happen

PhilosophyRunner

302Now to say what I think should happen

1) Different people should be payed differently based on their contribution to the companies profits, but based on two criteria:

a) A minimum wage that will allow a decent life. Even if some is performing poorly, they should still be able to earn a salary that allows them a decent life.

b)The ratio between the top and bottom wages should be within the bounds that all employees should have dignity. I can describe the qualitatively, but I would need more thought for a quantitative answer.

2) see 1) part b)

3)The limits described in a) and b) should be decided by the electorate of the country and be in the laws of the country. Within those limits, the owner of capital can decided.

Separately, there should be funding for innovation that allows for more competition. If any one of those 100 employees thinks they can create a better company, and have a reasonable idea and competence but lack the money to do so, there should be a common fund to do this taken from corporation tax.

The above point I could describe in terms of how more competition will change market value, but chose to leave out the term lest we get stuck on the terminology. -

Benkei

8.1kI don't think Marx was so prescient he wrote about problems that didn't exist until 100 years later. The industrialisation accelerated the outsized role of capitalists. And to be honest, I think we can go even a bit further back to the for-profit thinking with the first stock markets in the beginning of the 18th century but economic thinking was not yet entrenched in society at large then. That happened during the latter half of the industrial revolution which is why I prefer that as the starting point where capitalism (free markets, incorporation and for-profit statutes) really became part of the collective psyche and more or less coincided with Western governments passing generalised incorporation laws (second half of the 19th century). Since governments are usually slow on the uptake, it seems a safe bet by then it reflected the view of the majority of those privileged to vote.

Benkei

8.1kI don't think Marx was so prescient he wrote about problems that didn't exist until 100 years later. The industrialisation accelerated the outsized role of capitalists. And to be honest, I think we can go even a bit further back to the for-profit thinking with the first stock markets in the beginning of the 18th century but economic thinking was not yet entrenched in society at large then. That happened during the latter half of the industrial revolution which is why I prefer that as the starting point where capitalism (free markets, incorporation and for-profit statutes) really became part of the collective psyche and more or less coincided with Western governments passing generalised incorporation laws (second half of the 19th century). Since governments are usually slow on the uptake, it seems a safe bet by then it reflected the view of the majority of those privileged to vote. -

T_Clark

16.1kworkers aren't being paid a decent wage, in reality. And the reason they're not is partly determined by these OP questions — Mikie

T_Clark

16.1kworkers aren't being paid a decent wage, in reality. And the reason they're not is partly determined by these OP questions — Mikie

I gave criteria for determining the answers to the OP questions. You seem to think my answers aren't responsive to your questions. I don't see why.

But let's assume they are being paid a decent wage. They get enough to eat and live and have healthcare. Is that it? They deserve only that? What if they're the ones doing the lion's share of the work? Don't they deserve more than simply a "decent living wage"? — Mikie

I think workers deserve a decent life for themselves and their families. We can have a discussion as to what is required for a decent life. -

NOS4A2

10.2kIt’s a strange question because wages are decided and agreed upon before the worker makes a single product. These wages are determined by the market, literally by looking at the market place to determine what others are paying their employees, all of which is effected by the law of supply and demand. Pay too much you risk workers costing more than their contribution, resulting in lower profits, even losses. Pay too little you lose any competitive advantage. Even so, the profit should not go towards this or that worker, but towards the business at large, because the business is providing income to everyone involved.

NOS4A2

10.2kIt’s a strange question because wages are decided and agreed upon before the worker makes a single product. These wages are determined by the market, literally by looking at the market place to determine what others are paying their employees, all of which is effected by the law of supply and demand. Pay too much you risk workers costing more than their contribution, resulting in lower profits, even losses. Pay too little you lose any competitive advantage. Even so, the profit should not go towards this or that worker, but towards the business at large, because the business is providing income to everyone involved. -

Mikie

7.4kI don't understand your objection to "the market". An analogy - I say the electorate selected Biden as president. You say the electorate had nothing to do with it, it was real people. Of course it was real people, and the collection of people who did the voting within the system, I am referring to as the electorate. Both are correct. — PhilosophyRunner

Mikie

7.4kI don't understand your objection to "the market". An analogy - I say the electorate selected Biden as president. You say the electorate had nothing to do with it, it was real people. Of course it was real people, and the collection of people who did the voting within the system, I am referring to as the electorate. Both are correct. — PhilosophyRunner

That's a fair point. My objection is a matter of emphasis. If we attribute Biden getting elected to the "electorate," that's true but it's far more abstract than it needs to be, especially if the question is something like "what reasons do people give for choosing Biden?"

There's also the question about whether you're definition of markets is accurate. I'm not sure it is. A market can also referred to a place -- or space -- where transactions occur. Where things are traded, sold, bought, etc. If I go down to the market to buy things, for example, I'm not referring to people but a general space where economic activity occurs.

So briefly, I think it's often used to avoid more concrete discussions. Not by you, necessarily, but by those in power.

A company decided to pay all of their staff the same amount - £36,000. This included software developers and clerical workers.

What happened? They struggled to hire software developers because other companies were willing to pay a lot more for this job (i.e they were paying below market value for the job - but I will only use the word in brackets for you). Equally they were inundated and overwhelmed with applications for clerical jobs because other companies were paying a lot less (i.e they were paying above market value for the job). — PhilosophyRunner

A good example. What my focus here would be is on who decided to give everyone an equal wage and why. Seems silly to me, but I'd be interested in the thought process behind it.

So there's no mystery: what I'm advocating for, ultimately, is not having these decisions exclusively be in the hands a tiny group. I'm not in favor of plutocracy in government, and I assume no one else here is either. I'm not in favor of it in business either. -

Mikie

7.4kI don't think Marx was so prescient he wrote about problems that didn't exist until 100 years later. — Benkei

Mikie

7.4kI don't think Marx was so prescient he wrote about problems that didn't exist until 100 years later. — Benkei

I don't recall Marx claiming that shareholders care solely about profit at the expense of everything else?

Maybe we're speaking past each other. To be clear: in my view, a shareholder cares more than simply profit above all else. In the long term, he's looking to make a profit, yes. But in the short term, he should care about the company itself, the community, the environment, potential corruption, mismanagement, the treatment of the workers. He should care about the company's longevity and quality control. Not just what the stock is doing today or tomorrow. And many shareholders do exactly this -- because they're long-term investors.

It's true that shareholders exist who want nothing but a profit in the short term, regardless of how they get it. Hedge funds are often good examples of this. Fire the workers, cut corners, bleed the company dry, then take the profit and leave. But to take this and generalize to all is a leap that isn't justified. It's like basing our view of human motivation on the behavior of a psychopath -- who make up less than 1% of the population. -

Mikie

7.4kI gave criteria for determining the answers to the OP questions. You seem to think my answers aren't responsive to your questions. I don't see why. — T Clark

Mikie

7.4kI gave criteria for determining the answers to the OP questions. You seem to think my answers aren't responsive to your questions. I don't see why. — T Clark

You did, I just think they were too abstract and wonder if we could get into more detail about how that would potentially look in real life.

I think workers deserve a decent life for themselves and their families. We can have a discussion as to what is required for a decent life. — T Clark

I share that thought. I think it includes wages and other material conditions, but also decision making participation. That's basically my whole argument. -

Mikie

7.4kIt’s a strange question because wages are decided and agreed upon before the worker makes a single product. — NOS4A2

Mikie

7.4kIt’s a strange question because wages are decided and agreed upon before the worker makes a single product. — NOS4A2

Not sure why it's strange. The question in this case is how that number is decided, and by whom.

These wages are determined by the market — NOS4A2

See above.

CEO makes 20 times an average worker in 1968.

CEO makes 350 times an average worker in 2022.

"The market" is an abstraction which explains nothing. The question is about real people. Prices and wages are decided upon by people.

Even so, the profit should not go towards this or that worker, but towards the business at large, because the business is providing income to everyone involved. — NOS4A2

The "business at large" is meaningless. The profits go somewhere. They're reinvested in workers, equipment, R&D, etc., or they're given to shareholders in dividends. These choices are made by real people. -

PhilosophyRunner

302A good example. What my focus here would be is on who decided to give everyone an equal wage and why. Seems silly to me, but I'd be interested in the thought process behind it. — Mikie

PhilosophyRunner

302A good example. What my focus here would be is on who decided to give everyone an equal wage and why. Seems silly to me, but I'd be interested in the thought process behind it. — Mikie

In this instance it was the owner of the business, who was also the CEO, who decided. He wanted to challenge the existing traditional structure of how people were paid and hoped to foster a new ethos of equity among his staff. He also hoped to attract employees that believed in this ethos. At first this worked when the company was small and the only employees were founders.

When the company expanded, he ran into problems that were a result of what I call market forces. The average salary for a software developer in London is £66,000 (this is what I refer to as their market value). The average salary of a clerk in London is £27,000 (market value). He offered both a salary of £36,000.

The software engineers knew that this was less than they can earn elsewhere (below market value offer), so didn't apply. The clerks knew this was more than elsewhere (above market value) and overwhelmed the company with applications.

The CEO and business owner had to readjust and move the salaries to be more in line with the market values I referenced above (I don't know the exact values they now pay their staff now).

So there's no mystery: what I'm advocating for, ultimately, is not having these decisions exclusively be in the hands a tiny group. I'm not in favor of plutocracy in government, and I assume no one else here is either. I'm not in favor of it in business either. — Mikie

I agree. See my previous post where I outline how I think it should work (as opposed to the above which is how I think it currently works). -

T_Clark

16.1kI share that thought. I think it includes wages and other material conditions, but also decision making participation. That's basically my whole argument. — Mikie

T_Clark

16.1kI share that thought. I think it includes wages and other material conditions, but also decision making participation. That's basically my whole argument. — Mikie

My father spent the last 15 years of his 45 year career at a large chemical manufacturing company working on ways to get labor and management to work together. He always said the workers thought it was great and management did whatever they could to throw monkey wrenches in the machinery. He always saw it not as a way to help the workers, but rather as a way to improve the productivity of the whole enterprise. He thought that would help both workers and the company. -

Mikie

7.4kHe always said the workers thought it was great and management did whatever they could to throw monkey wrenches in the machinery. He always saw it not as a way to help the workers, but rather as a way to improve the productivity of the whole enterprise. — T Clark

Mikie

7.4kHe always said the workers thought it was great and management did whatever they could to throw monkey wrenches in the machinery. He always saw it not as a way to help the workers, but rather as a way to improve the productivity of the whole enterprise. — T Clark

I’m sure he’s right. There’s a lot of good scholarship on the era between roughly 1945-1975, when unions were stronger and distribution more equitable. Turns out this was good for companies as well.

Really? What do you think his surplus value extraction was all about? Not about profit? — Benkei

What does that have to do with shareholder motivation? They’re in it to make money, yes. The motivation is not to make money at the expense of everything else — that doesn’t make sense from an investment point of view. Any asset manager will tell you this. -

Benkei

8.1kSo the question is why you need to be this recalcitrant trying to explain economics to someone who actually worked with asset managers. It makes for tedious discussion. If you think the problem you're describing is new (50 years old) then you're ignoring a lot of history. I'd like to avoid reinventing the wheel. We've seen the same economic problems of today during the industrial revolution, during the times of the robber barons and now again. Take a cue or don't but I'm done. It's fucking annoying talking to someone who only thinks he knows a lot about economics.

Benkei

8.1kSo the question is why you need to be this recalcitrant trying to explain economics to someone who actually worked with asset managers. It makes for tedious discussion. If you think the problem you're describing is new (50 years old) then you're ignoring a lot of history. I'd like to avoid reinventing the wheel. We've seen the same economic problems of today during the industrial revolution, during the times of the robber barons and now again. Take a cue or don't but I'm done. It's fucking annoying talking to someone who only thinks he knows a lot about economics. -

unenlightened

10kwhy you need to be this recalcitrant — Benkei

unenlightened

10kwhy you need to be this recalcitrant — Benkei

One of the mysteries of life.

My economics starts from 2 principles.

1. “If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe” Carl Sagan.

2. "Property is theft!". Proudhon.

Accordingly, 100 people who contribute to producing something automatically incur a debt to the rest of the world for the value of the resources they have appropriated to themselves, and the damage they have caused to other resources, ie the environment. Thus every fenced off field owes a debt to wilderness, as does every cut down tree, every mine and quarry, and every factory. This unpaid debt is now being called in by way of climate change and environmental degradation.

@Mikie actually knows this, but somehow cannot integrate it into his economic understanding. He is alas not alone in this. -

Isaac

10.3k

Isaac

10.3k

Absolutely.

Which is why the way forward is not to be found in company organisation, but rather in progressive taxation. The population and future populations deserve to be compensated for their loss to whatever degree brings them up to an acceptable standard of living. Thus the government takes, from those who have benefited, enough to pay the bill due to those who have given.

Or... from each according to their ability, to each according to their need. -

ssu

9.8k

ssu

9.8k

Likely those people who own the property and/or basically who have gotten the 100 people together for the project make a suggestion on how the profits are going to be divided and then the rest 100 or so either accept it or say no thanks.Let's say only a handful of people own the property. I'm not assuming everyone is equal, I'm asking how distribution of profits is decided -- and by whom. — Mikie

If somebody makes a suggestion that people aren't excited with, then time for another proposal. When there are so many people involved, then some kind of rather simple arrangement is likely done. If the enterprise is small and short timed likely it's divided by some equal basis, because nobody has the time for every 100 to haggle their share individually. And of course it can be a cooperative or then stock is issued: those who buy the stock then decide what to do with the profits. Or then the profits go to the members of the cooperative equally.

And lastly, someone will just want a fixed payment for his or her work and doesn't care if there are potential huge profits or not. This person participates in the enterprise, but isn't part of it, just someone contracted to it.

Basically the question goes to the theory of a business or company: companies are only complex agreements between people, but simply perform the same task when you buy a service from someone. After all, you can either own a company or then simply buy the work you want from other people separately.

You can instantly observe how difficult and disorganized would be you buying every day the work from either other companies and individual people the work. Hence the need for longer contracts. -

Moliere

6.5k(3) Who decides (1) and (2)? — Mikie

Moliere

6.5k(3) Who decides (1) and (2)? — Mikie

(1) and (2) are decided by class, I think. It's not an individual which makes a labor market. Markets and profits and money are made possible by the modern nation state. And nations are ruled by class interests, first and foremost. Once those are satisfied then other projects can be taken on, and are taken on (usually as a way to demonstrate how one's nation is superior to another), but the ruling class will get theirs first (or the nation will collapse).

"Theirs", from my vantage, is however much they are able to get away with taking. So, in a backwards way, it's also up to the under-class as well as the over-class, because the under-class can push back and demand more (since the over-class depends on the under-class). But here "decision" and "fair" and "should" stop being efficacious, or at least honest if they are efficacious words. Seeing the labor market as a balance of power between classes changes it from a moral problem to a political one. -

NOS4A2

10.2k

NOS4A2

10.2k

Accordingly, 100 people who contribute to producing something automatically incur a debt to the rest of the world for the value of the resources they have appropriated to themselves, and the damage they have caused to other resources, ie the environment. Thus every fenced off field owes a debt to wilderness, as does every cut down tree, every mine and quarry, and every factory. This unpaid debt is now being called in by way of climate change and environmental degradation.

Every time a bird puts a twig on his nest he is incurring a debt to wilderness. -

unenlightened

10kEvery time a bird puts a twig on his nest he is incurring a debt to wilderness. — NOS4A2

unenlightened

10kEvery time a bird puts a twig on his nest he is incurring a debt to wilderness. — NOS4A2

And the penalty for this bad behaviour is to be shot and eaten. :death: -

Mikie

7.4kIf you think the problem you're describing is new (50 years old) then you're ignoring a lot of history. — Benkei

Mikie

7.4kIf you think the problem you're describing is new (50 years old) then you're ignoring a lot of history. — Benkei

I’m not sure you’re understanding what I consider a problem. I’m not saying shareholders don’t want to make money. Shareholder primacy theory is indeed fairly new, and began being adopted and implemented in the 1970s and 80s. Part of this is the assumption about a typical shareholder that you mentioned, which echoes Friedman.

Perhaps the biggest flaw in the shareholder value myth is its fundamentally mistaken idea about who shareholders “really are.” It assumes that all shareholders are the same and all they care about is whats happening to the company’s stock price — actually all they care about is what’s happening to the stock tomorrow, not even 5 or 10 years from now.

Shareholders are people. They have many different interests. They’re not all the same. One of the biggest differences is short term and long term investing. Most people who invest in the stock market are investing for retirement, or perhaps college tuition or some other long term project. — Lynn Stout

https://youtu.be/k1jdJFrG6NY

Take a cue or don't but I'm done. It's fucking annoying talking to someone who only thinks he knows a lot about economics. — Benkei

I don’t think that. I mentioned before there’s good scholarship on all of this. Maybe we’ve read different things. Honestly I think it’s just misunderstanding— which is my fault, as I tried to be clear and failed. Not sure the abrupt frustration is warranted, but so be it. -

Mikie

7.4kMikie actually knows this, but somehow cannot integrate it into his economic understanding. — unenlightened

Mikie

7.4kMikie actually knows this, but somehow cannot integrate it into his economic understanding. — unenlightened

Integrate what? This:

100 people who contribute to producing something automatically incur a debt to the rest of the world for the value of the resources they have appropriated to themselves, and the damage they have caused to other resources, ie the environment. — unenlightened

Well yes, no kidding. Does this really need to be stated? The “100 people produce something” is a casual example to get the discussion going. To object to this part of the OP completely misses the point, which really concerns the distribution of profits. Anyone who’s read a word of what I’ve wrote here for years knows that I don’t think production or private ownership occurs in a vacuum. I’ve also written often about “externalities” — especially environmental degradation. So I was, and still am, at a loss regarding your response.

Why not simply answer the questions? -

Mikie

7.4kLikely those people who own the property — ssu

Mikie

7.4kLikely those people who own the property — ssu

those who buy the stock then decide what to do with the profits — ssu

In terms of large corporations, this seems to be the case.

But then they vote basically to give the profits to…themselves! What a shocker. So roughly 90% of the net earnings go back up the shareholders in the form of dividends and buybacks. Those decisions are made by the board of directors, who are voted in by the shareholders.

If this is truly the state of things, the question becomes: is it just? Has it always been this way? Etc. -

ssu

9.8k

ssu

9.8k

In all kinds of cases.In terms of large corporations, this seems to be the case. — Mikie

If you start an enterprise with your friends, likely the division will be done similarly: if people will give majority of their time and labour to a project or put in their money, the majority want something on paper. And hence for example even if the business is small, they may opt for a company that issues stock. Also people may will want to have that limited liability. If the project goes south, the company will go bankrupt, not them or one of them.

It's actually quite similar to if people want to do something together even without a profit making objective, they form an association. With an association, they can buy equipment or gear for example for a hobby or for a cause and that property then belongs to the association, not someone specific. Otherwise it would be a hassle to own together stuff when people can come and go.

First and foremost, these are things about practicality. Starting from things like which thing is more easy: simply buy the services or then form a company.

I think you are confusing two things here. The reasons why people have invented companies and then why societies have become as they are and have companies and corporations in the role they have.If this is truly the state of things, the question becomes: is it just? Has it always been this way? — Mikie

You see, your example of 100 people forming an enterprise has a lot to do with the society, the business environment and all kinds of different variables than just the form of the business enterprise. "Is it just" is more of a societal question than an organizational question. A stock company is basically just: the owners have power to decide on company matters based on the amount of stock they have. And so is a cooperative basically just. There's nothing profoundly more "just" in one or the another.

Unjustness creeps in when one person or side has a large advantage in the negotiation power: it's a bit different if you start an enterprise and the 99 are well off business professionals and entrepreneurs themselves or lets say you offer 99 migrant workers a job who otherwise would face deportation.

Hence for example the historical unjustness of capitalism in the 19th Century should be understood that it came from an historical environment where feudalism still had it's roots and where the new working class came basically from landless agrarian workers. -

Isaac

10.3k

Isaac

10.3k

I think possibly the counterargument being made here is that the distribution of profits doesn't have a moral component - in other words, there's no answer to "how ought the profits be distributed?"

A corporation ought be a voluntary arrangement of people and so ought to able to come up with whatever arrangements it wants regarding distribution. The problems only arise because having appropriated the means of production, those in control of the corporation can effectively mandate involvement. But then the fairer distribution of profits becomes an patch, a temporary solution to another problem. People, ought to be able to engage voluntarily in corporate ventures. The way we can do that is for those ventures to be required to provide fair compensation for the social and environmental resources they've used. the people not involved can then live freely, or get involved, as they wish, and the matter of profit distribution becomes irrelevant (if you don't like the arrangement on offer, walk away).

Obviously, getting there from here then becomes the most significant issue. We can't (outside of theory) just give everyone their acre. What we can do is demand enough tax to fully compensate for the losses and use it to fund a Universal Basic Income which would enable people to either voluntarily form corporations with whatever profit sharing arrangements they're happy with, or not.

Alternatively, a strict and generous minimum wage plus a system of environmental charges and fines for transgressions would do the same job, I think. Any distribution has to at least meet that lower standard and from then on can be whatever.

If you want to keep with current arrangements and then ask how corporations ought to distribute profits, I think that seems like the old moral paradox about how one ought to murder gently (assuming you know that one). You're really asking "given that corporations unjustly create conditions where people are forced into joint ventures with them, then how ought they justly distribute profits" which sounds like an odd question.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum