-

J

2.5kCertainly, on a common sense usage of "possible," I should not worry about the possibility that giving my child milk will transform them into a lobster — Count Timothy von Icarus

J

2.5kCertainly, on a common sense usage of "possible," I should not worry about the possibility that giving my child milk will transform them into a lobster — Count Timothy von Icarus

Agreed. But don't we also have to agree that this is not necessarily true? Otherwise, where do we draw a conceptual line between what is necessary and what is overwhelmingly likely? But by all means, let's not worry about any wildly unlikely things.

You have it that the specific individual proposition involving Washington's birth is necessarily true in virtue of the particular event of Washington's birth. This is not how it is normally put at least. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Bracketing whether this is ever normally put (!), I don't see what's wrong with it. Isn't it an instance of the general principle? It seems clear enough. The general principle, if I understand you, would be "a proposition is necessarily true if the fact that it describes obtains." (This invokes the "adequate to being" idea, which I find a bit opaque, but no more so than any other attempt at a correspondence theory of truth.)

"I think the Principal of Non-Contradiction is enough. Something cannot happen and have not happened. George Washington cannot have been the first US President and not have been the first US President (p and ~p). — Count Timothy von Icarus

Here's the real rub. I can't remember how much of the Kimhi thread you followed, but one of the major themes was whether PNC applies to both logical and physical space, and why. We know ~(p and ~p) (in most logics), but why is it that physical occurrences cannot both obtain and not obtain? Is it because of the PNC, or is the explanatory arrow reversed, with the PNC being as it is because it reflects something about the way the physical world must be actualized? Or, ideally, both -- we're equipped with rational equipment that is perfectly suited to the way the world in fact operates?

"GW was President in our world, but there are other worlds in which he was not." When we say this, are we saying the same thing as "The (logical version of the) PNC applies in our world, but there are other worlds in which it might not"? Or, if we don't like possible-worlds talk, is saying "GW might not have been president" the same kind of statement as "The (logical) PNC might not apply"? There's a pretty stark difference, seems to me, and it's tied directly to how we should understand "necessity." But I'll pause here and see what you think. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

I'll go over the argument once again for you. You suggested that a possible world semantics for modal logic was counterintuitive. I'm asking you what might be concluded from this, by considering how one might react to someone who claimed that the classical inference rules were counterintuitive. You cannot say that someone is wrong concerning their intuition. If they do think classical inference counterintuitive, what a teacher might do is work through some examples to show them how classical inference leads to coherent deductions, allowing one to express one's ideas consistently.The classical inference rules are not counterintuitive. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Similarly, all a teacher can do for someone who finds possible world semantics of modal logic counterintuitive is to show that the results are coherent and consistent, and hope that the pieces that seem counterintuitive fall in to place, becoming intuitive as the logic is learned.

You would I hope agree that logic is a discipline, that it requires some effort to follow and understand and that it does considerably more than simply to reinforce one's intuitions.

Nor will mere intuitions do as a basis for any shared argument, given that our intuitions are not all held in common. Intuition cannot serve as a basis for rationality.

Modal logic, including possible world semantics, is an accepted part of formal logic, with a very strong foundation and application across diverse fields, including many outside of philosophy. Choosing to use it is not so much like choosing between frequentist and Bayesian approaches to probability, as choosing between integral and differential calculus. You may use the tool appropriately to the task, with confidence. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

The other philosophers here are quite entitled to differ with Klima on several points. Most obviously, they may question whether his notion of metaphysics is indeed "proper"; they might also ask whether his articulation of "proper metaphysics" really does not match our best, consistent and coherent account of modality; and they might point out that if a theory does not fit well with out best logic, that provides us with ample reason to question not the logic, but the theory."let's ditch this system because it isn't consistent with the proper metaphysics." — Count Timothy von Icarus -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

That was in reference to Quine though. "This system implies 'Aristotelian essentialism,' (at least as he understood it), therefore it is flawed."

Now that is a fine point to make. If formalism implies a position one takes to be false, it is indeed deficient. The point is rather that one cannot then turn around and point at an "approved" formalism as evidence of the rightness of a metaphysical position.

This same point is made re Quine's methods in metaontology. That "there exists at least one Hercules that is strong" implies an ontological commitment to the existence of Hercules, but not strength, is obviously not neutral. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

It seems worth pointing out that PNC will apply throughout all possible worlds.

Yes. But if a metaphysical position, understood formally, entails a contradiction, that is reason to reject the metaphysical position. Which is to say that our metaphysics ought not be inconsistent.The point is rather that one cannot then turn around and point at an "approved" formalism as evidence of the rightness of a metaphysical position. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Before we continue, it would be useful to set out what "Aristotelian essentialism" might be, in its variations. It is not monolithic, and we may well find some agreement .

Barcan seems sympathetic, but Kripke less so. In formal terms, we can differentiate between fixed and non-fixed domains.

Fine would have us consider essences in terms of definitions rather than necessary properties. Now it remains that it is very unclear to me what an essence is for you, but I suspect that you would find Fine more to your liking than Barcan. Fine wants to rescue essences from modality. -

Banno

30.6kPart Four.

Banno

30.6kPart Four.

Quine reiterates his argument, further extending it to attributes. To be extensional, one ought be able to substitute equivalent terms without altering truth values, but Quine argues that this does not work in modal contexts. Hence for Quine modal contexts are "intensional".

One way to think about the distinction between intensional and extensional contexts is that a predicate in an extensional context refers to the very objects picked out, while in an intensional context the predicate refers to the attribute doing the picking...

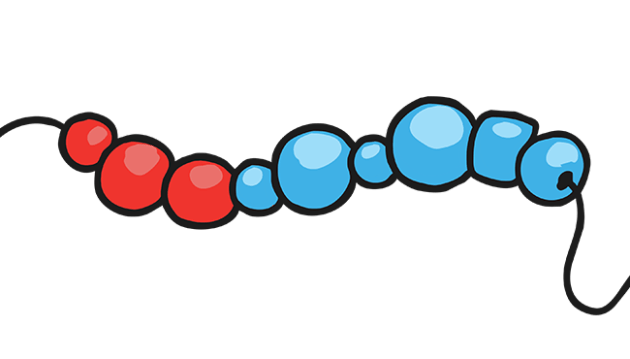

Suppose this is our domain...

We can give the beads proper names by numbering them from left to right. The beads are 1,2,3, 4,5,6,7,8,9. Intensionally, the red beads are those for which "having the attribute red" is true. Extensionally, red = {1,2,3}. it just is those beads.

Quine takes the example

and the identity(39) The attribute of exceeding 9 = the attribute of exceeding 9

and constructs the falsities(24) The number of planets = 9

andThe attribute of exceeding the number of the planets = the attribute of exceeding 9

(40) (∃x)(the attribute of exceeding x = the attribute of exceeding 9)

Attributes, as remarked earlier, are individuated by this principle: two open sentences which determine the same class do not determine the same attribute unless they are analytically equivalent.

For those beads, that a bead has the attribute of being red is discovered by looking to see what colour the bead is. It is therefore not analytic, but synthetic. Being a member of {1.2.3} on the other hand, is analytic. Being red and being a member of {1,2,3} are not the very same.

Notice also {1} might have been blue. But it would still be a member of {1,2,3}.

For Quine, any attribute might have been otherwise, and so for Quine there are no essential properties. But every item in the domain is a bead; so while it is possible for 1 to have been blue, it is not possible for 1 not to be a bead and still be 1. 1 is necessarily a bead, and not not necessarily red. Being a bead is part of the (Aristotelian?) essence of 1, but being red is not.

Of course, Quine would point out that we arbitrarily limited our domain to beads. And he would be correct. What counts as an essential attribute is decided not by examining the beads, but in the linguistic act of setting up the domain. Essence, then, is an arbitrary part of the language game. -

Banno

30.6kMuch the same move is seen in Kripke's Identity and Necessity, where this lectern is necessarily made of wood. It's not that a lectern could not have been made of ice, but that by this lectern we only pick out the wooden one. Our language game is set up so that if we are talking about any lectern not made of wood, then we are not talking about this lectern.

Banno

30.6kMuch the same move is seen in Kripke's Identity and Necessity, where this lectern is necessarily made of wood. It's not that a lectern could not have been made of ice, but that by this lectern we only pick out the wooden one. Our language game is set up so that if we are talking about any lectern not made of wood, then we are not talking about this lectern. -

J

2.5kI like the bead illustration as a guide to intension/extension.

J

2.5kI like the bead illustration as a guide to intension/extension.

Being a bead is part of the (Aristotelian?) essence of 1, but being red is not. — Banno

Interestingly, we could number a set of objects extensionally without knowing what they were. So "being a bead" (or any other common noun) wouldn't come into play. Must something serve as an "essence", though? "Object"? "The thing I am speaking about"? Relates to Kripke.

I might have missed a response somewhere, but I'm still curious about this, from Part 3.

An object, of itself and by whatever name or none, must be seen as having some of its traits necessarily and others contingently, despite the fact the latter traits follow just as analytically from some ways of specifying the object as the former traits do from other ways of specifying it.

— Quine, 155

I have a number of questions about this analysis, but let me start with this: What does Quine mean by "must be seen"? Is this referring back to the act of quantification? Is this a doctrine (like "To be is to be the value of a bound variable") that would state, "To be a bound variable in modal logic is to entail a choice of some necessary predicate(s)"? — J -

Banno

30.6k↪Banno I like the bead illustration as a guide to intension/extension. — J

Banno

30.6k↪Banno I like the bead illustration as a guide to intension/extension. — J

I'm please.

I chose it also in order to draw comparisons to PI§42 regarding simples. What is the simple here? What are the individuals? We treated the beads as the individuals. I left out the string entirely; the domain might have been set to {beads, string}. I might equally validly have treated the colours as individuals - that the domain was {blue, red}. What counts as an individual in the domain is stipulated.

No, you didn't. I had intended to come back to this. It needs a longer post delving into the context. Next post, maybe.I might have missed a response somewhere — J -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

So this is a long argument setting out w "the only hope of sustaining quantified modal".

The page referred to just before your quote...

The Aristotelian notion of essence was the forerunner, no doubt, of the modern notion of intension or meaning. For Aristotle it was essential in men to be rational, accidental to be two-legged. But there is an important difference between this attitude and the doctrine of meaning. From the latter point of view it may indeed be conceded (if only for the sake of argument) that rationality is involved in the meaning of the word ‘man’ while two-leggedness is not; but two-leggedness may at the same time be viewed as involved in the meaning of ‘biped’ while rationality is not. Thus from the point of view of the doctrine of meaning it makes no sense to say of the actual individual, who is at once a man and a biped, that his rationality is essential and his two-leggedness accidental or vice versa. Things had essences. for Aristotle, but only linguistic forms lnave meanings. Meaning is what essence becomes when it is divorced from the object of reference and wedded to the word. — p.22

Quine's view of Aristotelian essentialism, it seems. So what is the "reversion to Aristotelian essentialism"? That some of the properties of a man are necessary, and some contingent.

What Smullyanis proposes (back a few paragraphs) is very close to Kripke's rigid designation. Quine would reject this on the grounds that some description must be associated with any proper name in order to "fix" it's referent. This wasn't rejected until Donnellan and Kripke's discussion of the topic, a few years later.

Quine's text is not helped by the juxtaposition of necessary and contingent, and the association of analyticity with necessity.

So let's be a bit pedantic and oppose necessity with possibility, and define these in terms of possible worlds, while also and distinctly opposing the analytic and the synthetic, such that the analytic is understood by definition while the synthetic is understood by checking out how things are in the world.

And as for contingency, let's leave it aside until we have a better foundation.

How's that looking?

is, then, what musty happen if modal logic is to avoid the issues with quantification that Quine raises - in this Quine is more or less correct, and the strategy Kripke adopts is pretty much the one Quine sets out - there are properties of things that are true of them in every possible world."must be seen..." — J

Whether these properties are "essential" is another question. -

Banno

30.6kMore on the conflation of necessity and analyticity:

Banno

30.6kMore on the conflation of necessity and analyticity:

but this is wrong. It should be:"Attributes, as remarked earlier, are individuated by this principle: two open sentences which determine the same class do not determine the same attribute unless they are analytically equivalent."

Attributes, as remarked earlier, are individuated by this principle: two open sentences which determine the same class do not determine the same attribute unless they are necessarily equivalent. -

J

2.5kSo let's be a bit pedantic and oppose necessity with possibility, and define these in terms of possible worlds, while also and distinctly opposing the analytic and the synthetic, such that the analytic is understood by definition while the synthetic is understood by checking out how things are in the world. — Banno

J

2.5kSo let's be a bit pedantic and oppose necessity with possibility, and define these in terms of possible worlds, while also and distinctly opposing the analytic and the synthetic, such that the analytic is understood by definition while the synthetic is understood by checking out how things are in the world. — Banno

I'm fine with this, as long as we understand that this terminological clarification has only sharpened the questions; it's not an answer in itself. We still want to know which things that we learn about the world (synthetic knowledge) turn out to be necessary, a la Kripke and (I guess) Aristotle, and what this says about possible worlds. Is there a possible world in which water is not H2O? Kripke says no. So is there a possible world in which a human is not a rational animal? I don't know if Kripke weighed in on this, but I would say yes.

"must be seen..."

— J

is, then, what musty happen if modal logic is to avoid the issues with quantification that Quine raises - in this Quine is more or less correct, and the strategy Kripke adopts is pretty much the one Quine sets out - there are properties of things that are true of them in every possible world.

Whether these properties are "essential" is another question. — Banno

So my suggested paraphrase, "To be a bound variable in modal logic is to entail a choice of some necessary predicate(s)" would be correct. And I think we're both saying that "necessary predicates" might turn out to be so ontologically minimal that they wouldn't fit the concept of "essential properties" at all.

Good. This highlights the distinction. -

Banno

30.6kWater just is the stuff made out of H₂O. The two terms "pick out" the very same stuff. There's nothing ontologically or epistemologically puzzling in our using two words to refer to the same thing, is there?

Banno

30.6kWater just is the stuff made out of H₂O. The two terms "pick out" the very same stuff. There's nothing ontologically or epistemologically puzzling in our using two words to refer to the same thing, is there?

And of course we might have done otherwise. We might have used the word "gold" for a group of different metals, but as it turns out we use it only for samples of that metal which has 79 protons in its nucleus. Did we discover, or did we stipulate, that it is "gold" that has an atomic number of 79? When scientific knowledge advances, are we changing the rules of our language, or are we uncovering facts that were already true? - but these are not mutually exclusive. We might arguably be doing both. In discovering that gold has 79 protons in its nucleus, we thereby changed the way we talk about gold.

What introduces necessity or possibility is the way the domain is interpreted as much as which properties are involved. -

Banno

30.6k"To be a bound variable in modal logic is to entail a choice of some necessary predicate(s)" — J

Banno

30.6k"To be a bound variable in modal logic is to entail a choice of some necessary predicate(s)" — J

This seems to presume a fixed domain - that the very same things exist in every possible world. If that is not presumed, then there might be bound variables that belong to possible but not actual individuals. ∃x◊P(x) might be true in some possible world, yet not in others. In which case it's not true that the bound variable x is necessarily P. There are possible worlds in which nothing is P. -

J

2.5kOK. I want to try out some thoughts about this, but first I want to clarify something about demonstratives.

J

2.5kOK. I want to try out some thoughts about this, but first I want to clarify something about demonstratives.

A proper name, according to Kripke, is a rigid designator. It picks out the thing named in all possible worlds. This does not mean, of course, that the thing named occurs in all possible worlds. It merely means that, if Banno exists in a world, the name must designate him and not some other. Importantly, Kripke points out that “the property we use to designate that man . . . need not be one which is regarded as in any way necessary or essential.” But at the same time, he says that the proper name itself won’t do as that property:

If one was determining the referent of a name like ‛Glunk’ to himself and made the following decision, “I shall use the term ‛Glunk’ to refer to the man that I call ‛Glunk’,” this would get one nowhere. One had better have some independent determination of the referent of ‛Glunk.’ This is a good example of a blatantly circular determination. — Naming and Necessity, 73

As we know, Kripke believes we should refer back to the origin story of a person in order to say what that “independent determination” is.

Now demonstratives are also rigid designators, according to Kripke. If I point out the window and say, “This cloud,” I have “baptized” the cloud and given it a rigid designation. The same caveat applies here as with proper names: The cloud may not appear in a given world, but if it appears, the designation “that cloud” is rigid.

I have two questions about this.

1) Is the “origin story” here simply a matter of my pointing and declaring? Doesn’t that seem the same as simply declaring a proper name, which Kripke says is circular? Then, if the “independent determination of the referent” is something else in the case of “that cloud”, what is it? Do we have to start talking in terms of molecular structure? But that is very un-Kripkean; that would be like “using a telescope” to identify a table; it’s not how we designate things.

2) Presumably there can be a possible world in which “that cloud” occurs but I do not. Does the cloud remain rigidly designated? There seems something odd about this. Do we want to say that, because I appear in a different possible world to baptize the cloud, my action carries over in some way to a world in which I never did so? There must be a better way to understand this.

Clarifications and insights welcome. -

sime

1.2kThat's what I thought. "One simple space" - so the step-wise structure disappears? That would presumably be the case if we implemented S5 in this way. — Banno

sime

1.2kThat's what I thought. "One simple space" - so the step-wise structure disappears? That would presumably be the case if we implemented S5 in this way. — Banno

I'm not quite sure what you meant there, but to clarify, a sample space S can fully and faithfully represent any relation that is defined over a countable number of nodes, in terms of a set of infinite paths over those nodes.

However, speaking of probability theory in the same breath as modal logic seems to be uncommon, in spite of the fact that modal logic and probability theory have practically the same models in terms of Boolean algebras with minor changes or small additional structure that has no bearing with respect to the toy examples that are used to demonstrate the meaning of the theories.

Notably, the logical quantifiers of any decidable theory that has a countable number of formulas can be eliminated from the theory by simply introducing additional n-ary predicate symbols. And since modal logic refers only to fragments of first order logic, then unless the modalities/quantifiers are used with respect to undecidable or uncountable sets of propositions, then they have no theoretical significance and one might as well just stick to propositional logic. To me this raises a philosophical paradox, in that the only propositions that give the quantifiers/modalities philosophical significance are the very propositions that the quantifiers/modalities cannot decide. -

Banno

30.6kI might reply to this by going back to the point I made a while ago, that there is a difference between probability and possibility, in terms of what we are doing. See if you agree.

Banno

30.6kI might reply to this by going back to the point I made a while ago, that there is a difference between probability and possibility, in terms of what we are doing. See if you agree.

Supose we put the beads in the image above in a bag, and pull out a bead. We know, since we know the number of beads, that there is one chance in three of the bead we pull out being red.This is classical, a priori probability. If we did not know the arrangement of the beads, we might apply some probability theory to an experiment in which we pull out a bead and return it to the bag, and over time we see that one in three of the beads we pull out is red. This is frequentist probability. A third, related approach might be to decide that there is a fifty-fifty chance of picking out a red bead, then to pick out and return the beads, adjusting one's estimation of the probability of picking out a red bead on the basis of the result. This is the Bayesian approach.

These are the sorts of things we do when reasoning about probability. We go out and experiment on the way things are, and describe the result one way or the other.

When we reason about modality, we do something a bit different. We stipulate, rather then experiment. We say things like "Supose you pull out a red bead..." We are not concerned with how the world actually behaves, but with how it might behave.

The similarity in models between probability and modality may lead us not to notice that what we are doing in each case is somewhat different. The one is an activity of discovery, the other an activity of stipulation. -

sime

1.2k

sime

1.2k

I can appreciate the distinction you are pointing out between stipulation and observation. Indeed, classical probability theory explicitly accommodates that distinction, by enabling analytic truths to be identified with an a priori choice of a sample space together with propositions that describe the a priori decided properties of the possible worlds in terms of measurable functions that map worlds to values. By contrast, statistical knowledge referring to observations of the sample space is encoded post-hoc through a choice of probability measure. I think this to be the most natural interpretation of classical probability theory, so I am tempted to think of probability theory as modal logic + statistics.

In particular, we can define a proposition p to be analytically true in relation to a possible world w if p is "True" for every path that includes w (or 'pathlet' if transitivity fails), in an analogous fashion to the definition of modal necessity for a Kripkean frame. (But here, I am suggesting that we say p is analytically true at w rather than necessarily true at w, due to the assumption that the sample space was decided in advance, prior to making observations).

By contrast, we can define p to be necessarily true at w if the set of paths including w for which p is true is assigned a probability equal to one. Thus a proposition can be necessarily true without being analytically true, by there existing a set of paths through w that has probability zero for which p is false. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

We need to be clear that, in those possible worlds in which I do not exist, "Banno" does not refer to anything.A proper name, according to Kripke, is a rigid designator. It picks out the thing named in all possible worlds. This does not mean, of course, that the thing named occurs in all possible worlds. It merely means that, if Banno exists in a world, the name must designate him and not some other. — J

Now go back to

In standard possible world semantics, the domain will be different in some possible worlds. In those worlds there need not be an x that is P. That is, ∃xP(x) would be false. It would not be the case that in every possible world something is P. If the domain is fixed - the same in all possible worlds - then a bound variable might have necessary properties; we might have ∃xP(x) in every possible world.To be a bound variable in modal logic is to entail a choice of some necessary predicate(s)" — J

When the domain varies, quantification does not necessarily imply that x has any essential properties, since x may not exist in all worlds.

So in the varying domain of standard modal logic, to be a bound variable does not entail a choice of some necessary predicates.

But I can see where this may come from. The Barcan formula, ∀x □P(x) → □∀x P(x), also relies on a fixed domain. may also be implicitly making use of a fixed domain - it is hard to say.

Kripke is not using a fixed domain.

Hence the need to note that there are possible worlds not blessed with my presence. -

J

2.5kThis is helpful, thanks. But even if the domain is fixed to include only those worlds in which "that cloud" exists . . . must I (the "baptizer") necessarily be in that domain as well, in order for that cloud to be designated as "that cloud"? And there's still the question of what property I am picking out besides "'that-cloud'-ness."

J

2.5kThis is helpful, thanks. But even if the domain is fixed to include only those worlds in which "that cloud" exists . . . must I (the "baptizer") necessarily be in that domain as well, in order for that cloud to be designated as "that cloud"? And there's still the question of what property I am picking out besides "'that-cloud'-ness."

there are possible worlds not blessed with my presence. — Banno

Good line for an obituary: "An eminent logician, the late X claimed he was necessary in all possible worlds, but alas, we now discover this is untrue." -

Banno

30.6kIf one was determining the referent of a name like ‛Glunk’ to himself and made the following decision, “I shall use the term ‛Glunk’ to refer to the man that I call ‛Glunk’,” this would get one nowhere. One had better have some independent determination of the referent of ‛Glunk.’ This is a good example of a blatantly circular determination. — Naming and Necessity, 73

Banno

30.6kIf one was determining the referent of a name like ‛Glunk’ to himself and made the following decision, “I shall use the term ‛Glunk’ to refer to the man that I call ‛Glunk’,” this would get one nowhere. One had better have some independent determination of the referent of ‛Glunk.’ This is a good example of a blatantly circular determination. — Naming and Necessity, 73

This occurs as part of an extended discussion. Kripke does offer the causal theory as a solution, but there are problems.

I'd take a different track in characterising the failure to name Glunk as "Glunk" here. The issue at hand is what it might be to have effectively named an individual. It is worth stating something that is I hope quite obvious, but which tends to get lost in these considerations. A proper name works only if those in the community agree as to it's use. If a proper name does not in our conversations pick out an individual unambiguously, then it has failed to be a name.

The problem isn't the circularity - circular arguments are not invalid, just unsatisfactory, unconvincing. An individual might well decide to use "Glunk" to refer to that individual they call Glunk, but then they would be subject to the difficulties noted by Wittgenstein - yes, private language. Kripke is quite right that we need something else to "better have some independent determination of the referent of ‛Glunk’". But that determination need not be the origin story, as Kripke suggests. We might just as well depend on the community in which "Glunk" picks out Glunk. If we agree that "Glunk" picks out Glunk, the presence or absence of an origin story is irrelevant.

Here I am departing from agreement with Kripke.

Here I am using much the same argument that I have used to reject Kripkenstein. -

Banno

30.6kSo now we are in a position to perhaps address this:

Banno

30.6kSo now we are in a position to perhaps address this:

A name is successful if it is used consistently and coherently by a community, and this regardless of the origin myth. The “independent determination of the referent” is the use in the community. Or if you prefer, and I think this amounts to much the same thing, we could use Davidson here, and say that the correct use of a name or a demonstrative is that which makes the vast majority of expressions that include it, true.1) Is the “origin story” here simply a matter of my pointing and declaring? Doesn’t that seem the same as simply declaring a proper name, which Kripke says is circular? Then, if the “independent determination of the referent” is something else in the case of “that cloud”, what is it? Do we have to start talking in terms of molecular structure? But that is very un-Kripkean; that would be like “using a telescope” to identify a table; it’s not how we designate things. — J -

Banno

30.6k2) Presumably there can be a possible world in which “that cloud” occurs but I do not. Does the cloud remain rigidly designated? There seems something odd about this. Do we want to say that, because I appear in a different possible world to baptize the cloud, my action carries over in some way to a world in which I never did so? There must be a better way to understand this. — J

Banno

30.6k2) Presumably there can be a possible world in which “that cloud” occurs but I do not. Does the cloud remain rigidly designated? There seems something odd about this. Do we want to say that, because I appear in a different possible world to baptize the cloud, my action carries over in some way to a world in which I never did so? There must be a better way to understand this. — J

Similarly, perhaps the reference still works in your absence becasue the reference is communal. "That cloud" remains a rigid designator. I doubt Kripke would agree with this. -

sime

1.2kA suggested computational analogy:

sime

1.2kA suggested computational analogy:

Non-rigid designators: Reassignable Pointers. Namely, mutable variables that range over the address space of other variables of a particular type. E.g, a pointer implementing the primary key of a relational database.

A rigid designator: A pointer that cannot be reassigned, representing a specific row of a table.

An indexical: A non-rigid designator used as a foreign key, so as to interpret its meaning as context sensitive and subject to change. -

J

2.5kA proper name works only if those in the community agree as to its use. If a proper name does not in our conversations pick out an individual unambiguously, then it has failed to be a name. — Banno

J

2.5kA proper name works only if those in the community agree as to its use. If a proper name does not in our conversations pick out an individual unambiguously, then it has failed to be a name. — Banno

Yes, a proper name is a convention. There is nothing to it beyond whatever a given community agrees is a sufficient "baptism."

But that determination need not be the origin story, as Kripke suggests. We might just as well depend on the community in which "Glunk" picks out Glunk. If we agree that "Glunk" picks out Glunk, the presence or absence of an origin story is irrelevant. — Banno

Hmm. I'm not so sure. The question is, Can "Community picks out Glunk" produce the same plausibility responses for us that "Glunk is picked out by his birth" does for Kripke?

Let me use the Queen Elizabeth example, as it's easier to quote directly. Kripke asks, "How could a person originating from different parents, from a totally different sperm and egg, be this very woman?" He acknowledges that others may have different intuitions about this, but for him, "anything coming from a different origin would not be this object."

So now we ask, "How could a person, Glunk, who is not so-baptized by his community, be this very person?" My intuition here is quite different from the Elizabeth-from-different-parents example. I would say that Glunk, under whatever name, is surely the same person. In other words, his name is not anything like an essential property. The name may be essential to how we designate him, but that's not the same thing.

Or if you prefer, and I think this amounts to much the same thing, we could use Davidson here, and say that the correct use of a name or a demonstrative is that which makes the vast majority of expressions that include it, true. — Banno

This is all well and good if the issue is indeed about the correct use of a name. But I think Kripke is talking about something different. It's the de re vs. de dicto question, yes? There has to be something about a rigid designation that transcends nomenclature or terminology. I appreciate that a community-wide agreement to name something is not the same as my personal, private-language decision to do so. But they are the same sort of thing. I don't think you can get to "independent determination of the referent" simply by letting "independent" mean "independent of me." I read Kripke as talking about an entirely different, ontological independence. Which comes with its own problems, of course, but this is a start. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

Well yes it is, becasue we make it so.his name is not anything like an essential property. — J

That's what Kripke did in positing possible world semantics as a way to give meaning to modal utterances. When you ask "What if Elizabeth had not had Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon (such an English name...) as her mother", you are thereby asking about Elizabeth... becasue you make it so.

And of course her name might have been Kate. In which case she would still be the very same person.

A name is not a property at all. That's why properties are represented as f,g,h and individuals as a,b,c... and names as "a","b","c"... Why? Becasue this is how the game is played; why does hitting the ball to the boundary count as a four? Why do to five cards of the same suit count as a flush? Becasue it's what we do. "What this shews is that there is a way of grasping a rule which is not an interpretation, but which is exhibited in what we call "obeying the rule" and "going against it" in actual cases."

The point may have been missed, so I'll restate it. "Independent determination" is irrelevant; what counts is that the folk in the conversation are talking about the same thing, to their own satisfaction. That is what it is to have effectively named an individual.

Kripke didn't understand Wittgenstein. That's why he felt obligated to write his other book, a book that was important for being so wrong.I read Kripke as talking about an entirely different, ontological independence. — J -

J

2.5kWhen you ask "What if Elizabeth had not had Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon (such an English name...) as her mother", you are thereby asking about Elizabeth... becasue you make it so.

J

2.5kWhen you ask "What if Elizabeth had not had Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon (such an English name...) as her mother", you are thereby asking about Elizabeth... becasue you make it so.

And of course her name might have been Kate. In which case she would still be the very same person. — Banno

If the name changes but she is still the very same person, then a name cannot be an essential property -- or, if you like, any sort of property. (Though I don't really see why 'is called Elizabeth by everyone who knows her' can't be a property. How is it different from 'has red hair'?)

But compare "She might have had different parents. In which case she would still be the very same person." You're not maintaining that this is true in the same way that the Eliz-vs-Kate case is true? Indeed, it isn't true at all, is it? We might mistakenly designate her as the same person, but that would be an error -- if we agree with Kripke about the importance of parentage. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

indeed, because a name is not a property...If the name changes but she is still the very same person, then a name cannot be an essential property — J

Property or predicate? How does the use of each differ? Extensionally, a name picks out an individual, and a predicate is a group (set, class...) of individuals. What is a property?(Though I don't really see why 'is called Elizabeth by everyone who knows her' can't be a property. How is it different from 'has red hair'?) — J

Supose we took a sample from Elizabeth's body and found that she could not have been the daughter of Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon... Who did we take the sample from? I think that as you specify your example with greater precession, you will find that the antinomy dissipates. Further, if it does not dissipate, then that very fact shows that you have not yet clearly stipulated what you are saying.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum