-

Banno

30.6kCheers, . It appears we now agree as to almost everything. The flower has many properties, perception makes some of these - colour, smell, shape - salient. Other properties are accessed via background knowledge (life cycle, chemistry, ecology). No single mode of access exhausts an object. We now have no epistemic veil and no private content; public objects anchor meaning; interpretation is world-directed. We both acknowledge the distinction beteween causal and epistemic mediation.

Banno

30.6kCheers, . It appears we now agree as to almost everything. The flower has many properties, perception makes some of these - colour, smell, shape - salient. Other properties are accessed via background knowledge (life cycle, chemistry, ecology). No single mode of access exhausts an object. We now have no epistemic veil and no private content; public objects anchor meaning; interpretation is world-directed. We both acknowledge the distinction beteween causal and epistemic mediation.

Perception is interpretive, mediated, and embedded in the world — and none of that entails indirectness. -

Esse Quam Videri

444Shape as seen or shape as felt? — Michael

Esse Quam Videri

444Shape as seen or shape as felt? — Michael

I’d say neither the look nor the feel of shape as such is identical to the mind-independent shape of an object. Shape is a structural property that can be accessed through different sensory modalities and at different scales, each of which presents only partial, resolution-bound aspects of that structure.

Molyneux-style results show that cross-modal access to the same structure is learned rather than innate, not that there is no shared object or that perception is indirect. Likewise, questions about “which scale is the real shape” rest on a false assumption that there must be a single privileged resolution. Shape descriptions are scale-relative but objective within a scale.

None of this requires that perceptual experience mirror shape as it is in the world, and none of it implies that perception proceeds via epistemic surrogates. It just means that perceptual access to structure is perspectival and modality-specific.

Then we're back to what I asked in this post (which I'll repeat below), which I don't think was addressed:

What's the difference between a bionic eye that is "integrated into perception such that judgments are still answerable to objects through ongoing interaction and correction" and a bionic eye that is "a surrogate whose adequacy depends on a generating process that stands in for the world"?

It just seems like there's a lot of special pleading here. — Michael

I think the reason this keeps sounding like special pleading is that you’re asking for a principled distinction I don’t think exists. On my view, there is no such thing as a physical process being an “epistemic intermediary” as opposed to a merely causal intermediary.

All perception—organic or bionic—involves deterministic transduction from the world to the nervous system. What makes something an epistemic intermediary is not its material constitution or causal role, but a theoretical decision to treat some inner item as what perception is of and as the standard against which correctness is assessed.

I reject that move. Perceptual error is explained by false world-directed judgment, not by mismatch with an inner surrogate. Once that assumption is dropped, the demand to distinguish epistemic from non-epistemic intermediaries simply dissolves.

As I said before, you can mean anything you like by "directness". I'm concerned with what it means in the context of the traditional dispute between direct and indirect realism, which I summarised here (which I'll repeat below), and which I also don't think was addressed: — Michael

And as I have said before, I'm rejecting a shared assumption (phenomenal mirroring) that the traditional framing is built on. I don't think direct realism requires taking on this assumption, but if you don't agree then that may be as far as we can go. I don't think re-litigating the traditional framing is likely to help move the discussion forward at this point. -

AmadeusD

4.3kBut even in those cases, I don’t think truth requires that the phenomenal character of experience reproduce those properties as they are in the world. — Esse Quam Videri

AmadeusD

4.3kBut even in those cases, I don’t think truth requires that the phenomenal character of experience reproduce those properties as they are in the world. — Esse Quam Videri

(i'm going to reply to this, then move on to your reply directly to me).

Interesting. So, is your position that even if tout court perception is indirect, we can derive truth from coherent experiences of properties we presume are out there in the world? Seems pretty murky to me, so assume I'm missing something there..

In neither case does perceptual truth require that properties be “directly present” in experience in the sense the naïve realist needs. — Esse Quam Videri

The reason I assume I'm missing something on hte murkiness, is because this doesn't actually say anything to me. Both situations require that the thinker determines their position on veridicality and then practicality and decide to which the term "true" should be applied (conceptually, they maybe contradictory 'objects' of thought, and so cannot be run together).

This seems intellectually expedient at the expense of truth. That said, "humans, under normal circumstances, look at the sky and see it as the colour we call blue" can be considered true, and so in a sense "the sky is blue" is going to be trivially true. But I do not think - and this may be where I diverge from much of the discussion - that that is any of interesting, complex or worthy of debate.

Are we maybe talking about two different things? There's a great paper that came out last year discussing this exact issue and concludes that the question of IR v DR needs to be set aside, as both are non-scientific, folk views which derive from equally substantial pre-scientific belief structures. I found that extremely unsatisfying and seemed more to be geared at sounding profound than anything to do with actually figuring the problem out. Although, I do think it's true among lay people (which the paper was talking about... very, very strangely).

My take has always been that perception is "near enough" reflecting the world to allow for intense, robust co-operation and for memory to function - but that doesn't give me naive realism. Hence, at some stage accepting some of Banno's takes - and at times having to just imagine he hasn't left his house.

"Perception is interpretive, mediated, and embedded in the world — and none of that entails indirectness"

Perfect example. This is total nonsense.

Identity is not comparison. — Esse Quam Videri

Hmm. I can't figure out what you're trying to say. I said that you haven't responded to what I've said there, as you restated the same thing I objected to without further elucidation. This doesn't help either. Can you clarify?

What I mean is that causal mediation does not by itself settle what perception is of. — Esse Quam Videri

Sure. That much is true - Kantian or not, we can't rely on our senses to tell us about what's out there by definition (this is important, though, for my objection) - so it could be a 1:1 match, or a 0:1 match, or a 0:0 match in the case of genuine hallucination. Definitely agree. But as I understand, that isn't the debate. It's whether or not one or other possibilityis the case. There are people who will deny the mediation of the senses to support a DR position. Banno avoids this (i am talking about him a lot because we've had several exchanges on this, at the expense of perhaps engaging with others on it and he did a great job of outlining a position I found totally incoherent to begin with) and it was that which had me move towards the understanding that many people have already set aside the debate I'm trying to have without telling anyone.

But it does not follow from this that the object of perception must be an inner representation rather than a mind-external object. — Esse Quam Videri

That's true - and I don't immediately claim that's the case. It isn't required to support an IR position. It could be 1:1, but if IR is true, we can never know. That seems fine to me and I don't get the discomfort many have with it. Science isn't going to fall apart and stop predicting things because we can't be sure what it's predicting in-and-of-itself. It predicts our perceptions almost perfectly, and that's "near enough" to ensure we do not pull the floor out by saying "science proves that perception is indirect, by way of indirect and unreliable perceptions". This is a confusion. "unreliable" here doesn't relate to whether or not it will work, or cohere. It is unreliable as an indicator of the actual object. Which, on my view, it is even if it's (from God's view) 1:1 in every single case. That part doesn't change the debate between IR and DR.

Saying that the mind “constructs images from sense-data” is already a philosophical interpretation of the science, not something the science itself establishes. All that science requires is that perception depends on causal processes. It does not require that awareness terminates in sense-data or inner pictures rather than in the world itself. — Esse Quam Videri

I am pretty confident it in fact does do this. We can physically watch photons hit cones/rods and transmute to neural signals and move into the brain for interpretation. There is nothing in an object that results in it's image in our mind. I do not think this is philosophically interpretive until you start saying things like "therefore, there's no way to..." or "because of this, we must accept...".

I'm not quite doing that. I'm saying that objectively, we do not see "objects" but images of them. This isn't an interpretation - it's how the mind works (subject to my explanation of why this doesn't defeat my reliance on the scientific findings). The interpretive aspect would be to call it "indirect" and I fully cop to that. Many will accept everything I've said and still call it "direct". I just can't make sense of that - seems a convenient lie to get on with things. Which you can do without the lie.

So the “chasm” you’re describing is not something science forces on us; it’s the result of adopting a particular representationalist model of perception. — Esse Quam Videri

I quite vehemently, and with elucidation above, disagree. It is exactly what we are presented with and exactly what this debate it supposed to categorize in a way that can capture experience and fact. The DRist must find hte physical object in the mental image. That's a chasm science provides also. So, this isn't just a one-way issue of interpretation - both avenues must grapple with the physiology of the eye, vision, the perceptual process and indeed, aberration in any of those, to get a "direct" aspect in to the mix. We only ever see hand-waving at this point. I trust you'll be a little more engaging :) Again, though, we may be having separate conversations but with each other lmao.

how the human perceptual system presents things — Esse Quam Videri

Is the same, without content as:

the sky as it is in relation to the human perceptual system under normal conditions. — Esse Quam Videri

They are literally the same exact thing, but the second includes an example. If you did not mean this, please do clarify.

“humans tend to experience the sky as blue” — Esse Quam Videri

Is the same as“the sky has properties such that, under normal conditions, it elicits blue-type responses” — Esse Quam Videri

I understand that you're trying to say that 1. is about perception, and 2. is about the sky. The sky isn't even an object. Both are about perception. Again, if you can clarify to tease these apart, I'd be happy to engage.

Those differ quite clearly in terms of:

subject matter (experience vs world), They do not differ. They both talk about (with a guise, in one example) how humans see things

truth conditions (facts about perceivers vs facts about the sky), Again, they amount to the same claim: Humans see things in X way (and then applied to the sky)

direction of explanation (mind → world vs world → mind) true, and doesn't change the content of the two claims being fundamentally the same thing. — Esse Quam Videri

For your claims to be different claims, you need to tell me something about hte sky sans human perceptions. Otherwise, that's all we're discussing as I see it. And probably should. Perhaps this is why i'm not groking you - that resistance is folly to me.

That is not true in ordinary perception — Esse Quam Videri

Yes it is. This may also be a fundamental we cannot come to terms on. -

NOS4A2

10.2k

NOS4A2

10.2k

What do you mean by senses "pointing" outward? The physics and physiology is just nerve endings reacting to some proximal stimulus (e.g. electromagnetic radiation, vibrations in the air, molecules entering the nose, etc.) and then sending signals to the brain. If there's any kind of "motion" involved, it certainly does appear to be towards the head.

Senses have a direction that tends toward the outside of the body. It’s why we have those holes in our skull where our eyes, nose and mouth are, so they can better interact with the environment. It’s why you turn your head towards something or open your eyes in order to see it better. This simple common sense ought to inform one of what it is he is seeing. -

Banno

30.6kConsider that there are two subspecies of humanity such that what one sees when standing upright is what the other sees when standing upside down. Both groups use the word "up" to describe the direction of the sky and "down" to describe the direction of the floor. Firstly, is this logically plausible? Secondly, is this physically plausible? Thirdly, does it make sense to argue that one subspecies is seeing the "correct" orientation and the other the "incorrect" orientation? Fourthly, if there is a "correct" orientation then how would we determine this without begging the question? — Michael

Banno

30.6kConsider that there are two subspecies of humanity such that what one sees when standing upright is what the other sees when standing upside down. Both groups use the word "up" to describe the direction of the sky and "down" to describe the direction of the floor. Firstly, is this logically plausible? Secondly, is this physically plausible? Thirdly, does it make sense to argue that one subspecies is seeing the "correct" orientation and the other the "incorrect" orientation? Fourthly, if there is a "correct" orientation then how would we determine this without begging the question? — Michael

& , please excuse my interjecting. How would we be able to distinguish between these two populations?

Suppose Fred presents himself to your laboratory, and you are tasked with deciding which population he belongs to. How do you proceed?

I don't see that you can.

And the mistake here seems to be that of presuming there is a private notion of up and down; that is, there is no fact of the matter for Fred to belong to one population rather than the other.

So I'll opt for saying that Michael's scenario is incoherent.

Added: I think, although I haven't worked through it yet, that by treating "up" and "down" as indexicals we could show there to be only one population. Indexicals don’t tolerate private degrees of freedom. To master “up” is to participate competently in a network of practices: standing, pointing, correcting, navigating, explaining, and so on. If two groups are indistinguishable across those practices, then — by the criteria that individuate the concept — they are the same group.

If we would claim there to be two populations, then we must have a way to differentiate them. The set up of the scenario rules out behavioural and functional differences. Pointing out that "up" and "down" are indexical rules out private differences - what's up for me is just what is up for me.

The pull toward “two populations” comes from smuggling in a Cartesian picture: an inner orientation space that could be inverted independently of outer practice. Once that picture is rejected — as both Wittgenstein and Davidson would insist — the multiplicity evaporates. -

RussellA

2.7kI think what’s really at issue here is how we understand truth and directness. On my view, truth doesn’t consist in a resemblance or mirroring between what’s in the mind and what’s in the world, but in a judgment’s being correct or incorrect depending on how things are — Esse Quam Videri

RussellA

2.7kI think what’s really at issue here is how we understand truth and directness. On my view, truth doesn’t consist in a resemblance or mirroring between what’s in the mind and what’s in the world, but in a judgment’s being correct or incorrect depending on how things are — Esse Quam Videri

Basically the choice between Indirect Reason and Direct Reason.

The question is, is it logically possible for the human mind to know “how things are” in a mind-external world.

Everything the human mind knows about the mind-external world comes through the five senses, meaning that it is logically impossible to know about the mind-external world independently of the human senses.

==============================

I realize this may sound like I’m simply assuming that judgments can be answerable to the world, but every account of truth has to take something as basic; — Esse Quam Videri

You are assuming the human mind can know about the mind-external world, but how is this logically possible? How is it possible to know what broke the window just by looking at the window? How is it possible to know the cause of our sensation of the colour red just from the sensation itself?

I directly perceive the colour red in my senses.

I reason about a causal chain that has caused my perception, such that in the world is a wavelength of light that enters my eye, and travels up my optic nerve as an electrical signal to arrive at my brain which I then perceive as the colour red.

I know my perception of the colour red directly. I know about the wavelength of light indirectly by looking at the display on a spectrometer. I know about the electrical signal indirectly by looking at the display on an oscilloscope.

Therefore, I only know about the wavelength and electrical signal indirectly by looking directly at a screen. This means that all my direct knowledge is visual, and from this direct visual knowledge I can indirectly reason about the causal chain.

From my direct visual knowledge of my perception of colour and directly looking at the screen of an spectrometer and oscilloscope I can indirectly reason about the causal chain that caused my perception of the colour red using “inference to the best explanation”.

It is logically impossible to directly know the cause of what I perceive, although I can indirectly reason about the cause of what I perceive.

The Indirect Realist uses “inference to the best explanation” to indirectly reason about the mind-external world.

The Direct Realist mistakenly believes that they can directly know the cause of an effect. They believe that they can directly know the cause in the mind-external world of their perceiving the colour red in their mind. Yet for the mind to directly know the mind-external is a logical impossibility.

We can indirectly infer using reason “how things are” in the mind-external world, but it is a logically impossibility for the human mind to directly know “how things are” in the mind-external world. -

RussellA

2.7kA sensation can prompt, occasion, or constrain a judgment, but it is the judgment that takes responsibility for saying how things are and can therefore be assessed as correct or incorrect. — Esse Quam Videri

RussellA

2.7kA sensation can prompt, occasion, or constrain a judgment, but it is the judgment that takes responsibility for saying how things are and can therefore be assessed as correct or incorrect. — Esse Quam Videri

There are two aspects to sensations and being truth-apt.

If I perceive a bent stick, then it is always true that I perceive a bent stick, therefore not truth-apt.

But if I perceive a bent stick and that is not how things are in the world, then it is not true that if I perceive a bent stick then in the world there is a bent stick. This is not a judgement. This is about how things are in the world. Perceptions can be truth-apt independent of any judgments made about them.

I can then make the judgement that “if I perceive a bent stick then in the world there is a straight stick”, and this judgement is certainly truth-apt.

As regards epistemic role, not only does a sensation take a responsibility in being about how things are or are not in the world but also judgement takes a responsibility in arriving at a proposition that is either true or false. -

Michael

16.9kSenses have a direction that tends toward the outside of the body. — NOS4A2

Michael

16.9kSenses have a direction that tends toward the outside of the body. — NOS4A2

What does it mean to say that senses have a "direction"?

It’s why we have those holes in our skull where our eyes, nose and mouth are, so they can better interact with the environment. It’s why you turn your head towards something or open your eyes in order to see it better. — NOS4A2

If you just mean to say that (most of) our sense receptors are situated on the outside of our body and react to things that exist outside the body then, to be blunt, no shit.

If you think that this is all it means for perception to be direct then you're very mistaken. Indirect realists don't disagree with any of the above.

Like your prior suggestion that we directly perceive an object if (and only if?) our sense organs are in direct physical contact with the object perceived, you're presenting a very impoverished interpretation of the issue. -

Esse Quam Videri

444

Esse Quam Videri

444

Thanks for the detailed reply. I think I now see fairly clearly where we diverge, and it’s not at the level of physiology, causal mediation, or even skepticism, but at a deeper metaphysical level about what counts as a feature of the world at all.

As I understand you, you’re assuming that any property defined in relation to human perceptual capacities collapses into a claim about perception rather than a claim about the world. On that assumption, statements like “the sky elicits blue-type responses under normal conditions” amount to nothing over and above claims about how humans experience the sky, and so the distinction I’ve been drawing between claims about experience and claims about the world simply disappears.

I reject that assumption. On my view, many genuine properties are relational without being mental or experiential in their subject matter. Properties like visibility, fragility, toxicity, solubility, or mass-relative-to-a-frame are all defined partly in relation to possible interactions or observers, but they are still properties of the world, with truth conditions fixed by how things are. I take ordinary color predicates to work in a similar way: they are world-involving, response-dependent properties, not reports about inner presentation.

This is why the two claims I’ve been distinguishing come apart for me. A claim about how humans experience the sky has its truth conditions in facts about experience. A claim about the sky’s standing in lawful relations to perceivers has its truth conditions in facts about the sky and those relations. If one denies that relational properties can be genuinely worldly, then of course that distinction collapses — but that is precisely the metaphysical constraint I’m resisting.

Once that difference is in view, I think it becomes clear why we’re talking past each other. Given your constraint, my position can only look like a terminological reshuffling. Given my rejection of that constraint, your insistence that everything here is “really about perception” looks like a substantive metaphysical narrowing of what the world can be like. At that point, the disagreement appears to be principled rather than clarificatory. -

Michael

16.9k

Michael

16.9k

I disagree with your assertion that we must be able to determine which group someone belongs to for there to be two different groups.

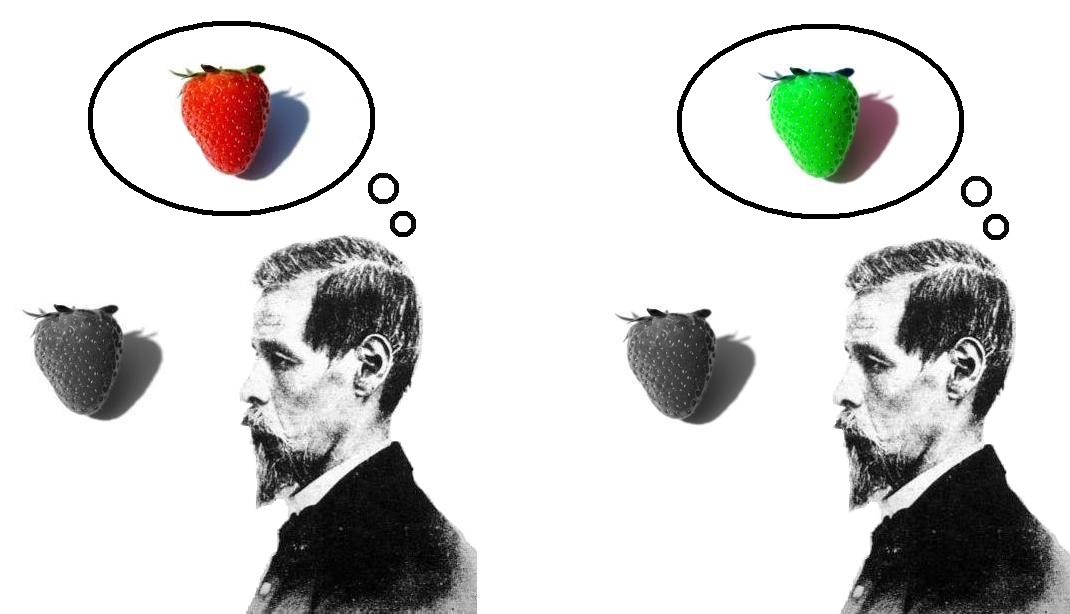

A scenario like the below, where two humanoid aliens agree that the strawberry reflects 400nm light and that the proposition "the blugleberry is foo-coloured" in their language is true, is intelligible:

-

Esse Quam Videri

444

Esse Quam Videri

444

I think this makes the disagreement very clear, and it turns on a specific claim you’re making: that it is logically impossible for the human mind to directly know how things are in a mind-external world, because everything we know comes through the senses. I agree entirely that all perceptual knowledge is sensory-mediated. But I don’t think mediation by the senses entails indirectness in the epistemic sense you’re assuming.

The inference you’re relying on is:

sensory mediation ⇒ only effects are directly known ⇒ causes can only be known by inference.

That inference is not a logical truth; it depends on a particular picture of perception as awareness only of inner effects from which outer causes must be inferred. The Direct Realist rejects that picture. On their view, perceptual awareness is a relation to the object itself via sensory capacities, not an awareness of an inner item from which the object is inferred as a cause.

So when I see a red screen, I am not directly aware of a mental effect and only indirectly aware of a wavelength. I am directly aware of the red screen as a mind-external object, even though my access to it is mediated by physiological processes. Those processes explain how perception occurs, but they are not what perception is of. Knowing that a wavelength and neural signals are involved is itself a further piece of knowledge, typically gained instrumentally and inferentially, but that doesn’t show that ordinary perception is awareness only of effects.

In short, the dispute is not about whether we use inference to explain causal chains — of course we do — but about whether perception itself is exhausted by awareness of inner effects. You take that to be a logical constraint; I take it to be a substantive philosophical thesis, and one the Direct Realist denies. -

Michael

16.9k

Michael

16.9k

There isn't a shared assumption of "phenomenal mirroring". There is the direct realist's claim that there is "phenomenal mirroring", because that is what it would mean for ordinary objects to be "directly present" in experience, and the indirect realist's claim that there might not be "phenomenal mirroring", because ordinary objects are not "directly present" in experience.

As for the "epistemic intermediary" I still fail to understand what you mean by the term. All indirect realists would mean by it is that we believe that the ball is blue and round because the ball appears blue and round, and that this appearance is a mental phenomenon, not the "direct presentation" of the ball's colour and shape. -

RussellA

2.7kI think this makes the disagreement very clear, and it turns on a specific claim you’re making: that it is logically impossible for the human mind to directly know how things are in a mind-external world, because everything we know comes through the senses. — Esse Quam Videri

RussellA

2.7kI think this makes the disagreement very clear, and it turns on a specific claim you’re making: that it is logically impossible for the human mind to directly know how things are in a mind-external world, because everything we know comes through the senses. — Esse Quam Videri

Your reply gives me plenty of food for thought.

Yes, I am saying that it is logically impossible for the mind to directly know how things are in a mind-external world, whereas you propose that the Direct Realist says that it is possible for the mind to directly know how things are in a mind-external world.

Perhaps it comes down to whether one accepts the rules of logic or not. I agree that logic is beyond justification.

For example, either one accepts the Law of Identity or one doesn’t. No amount of argument is going to prove that “whatever is, is”. No amount of argument is going to prove the Law of Contradiction, “nothing can both be and not be.' No amount of argument is going to prove the Law of Excluded Middle, that “Everything must either be or not be.' Logic is beyond explanation, It is something one either accepts or doesn’t accept.

Taking another example, the premises "Mars is red" and "Mars is a planet" support the conclusion "Mars is a red planet". The premises “the mind is only directly aware of the senses” and “the senses mediate between the mind and the mind-external world” support the conclusion "the mind cannot be directly aware of a mind-external world”.

Yes, it may be that the Direct Realist does not accept the logic that the mind cannot be directly aware of a mind-external world, but no amount of argument is going to persuade them otherwise. -

Esse Quam Videri

444

Esse Quam Videri

444

It looks like we've circled back to the starting point again, which is fine. I think this shows that we still have a disconnect at the level of foundational epistemic commitments. Your response attempts to push the discussion back into the traditional framing, whereas my view rejects that framing. It seems like we've hit bedrock here. -

Esse Quam Videri

444

Esse Quam Videri

444

I think this is a helpful clarification, but I want to push back on one point. The inference you’re calling “logical” is not on the same footing as the laws of identity, non-contradiction, or excluded middle. Those are formal constraints on any intelligible discourse whatsoever. By contrast, the premise “the mind is only directly aware of the senses” is not a law of logic; it is a substantive epistemological thesis.

The argument you give is valid if one accepts that premise, but that is exactly what the Direct Realist denies. The dispute is therefore not about whether one accepts logic, but about whether one accepts a particular account of what perceptual awareness consists in. Rejecting that premise is no more a rejection of logic than rejecting sense-datum theory or representationalism would be.

To put it another way: the claim that sensory mediation entails awareness only of inner effects is not logically forced. It is a philosophical interpretation of perception. The Direct Realist’s alternative claim is that perceptual awareness is a relation to mind-external objects via sensory capacities, not an awareness of sensory items from which external causes must be inferred. That difference is not something logic alone can settle.

So I agree with you that if someone simply takes it as a basic truth that the mind can only ever be directly aware of sensory items, then no argument will move them. But that cuts both ways. What’s at issue here is not acceptance or rejection of logic, but which epistemological starting point one finds more compelling. -

NOS4A2

10.2k

NOS4A2

10.2k

If you just mean to say that (most of) our sense receptors are situated on the outside of our body and react to things that exist outside the body then, to be blunt, no shit.

It was part of a larger argument. Their direction and the fact that they interact with the environment allow anyone to explain how we can see an apple, for example, while it precludes you from doing the same. You have no way to explain how you can see a perception, or some other mind-stuff, and are resigned to illustrating diagrams of apples in thought-bubbles floating around a head. -

Michael

16.9kYour response attempts to push the discussion back into the traditional framing, whereas my view rejects that framing. — Esse Quam Videri

Michael

16.9kYour response attempts to push the discussion back into the traditional framing, whereas my view rejects that framing. — Esse Quam Videri

I think the issue I have is that you're arguing that the traditional dispute is framed wrong whereas I think that the traditional dispute just means something else by "direct perception". So perception might not be direct in the way that they mean even if it's direct in the way that you mean. Once again, I'll refer to semantic direct realism.

Regardless, thanks for the discussion. -

Michael

16.9kIt was part of a larger argument. Their direction and the fact that they interact with the environment allow anyone to explain how we can see an apple, for example, while it precludes you from doing the same. You have no way to explain how you can see a perception, or some other mind-stuff, and are resigned to illustrating diagrams of apples in thought-bubbles floating around a head. — NOS4A2

Michael

16.9kIt was part of a larger argument. Their direction and the fact that they interact with the environment allow anyone to explain how we can see an apple, for example, while it precludes you from doing the same. You have no way to explain how you can see a perception, or some other mind-stuff, and are resigned to illustrating diagrams of apples in thought-bubbles floating around a head. — NOS4A2

On indirect perception of apples:

A society of people who wear visors with sensors on the outside and a screen on the inside that displays a computer-generated image of the outside can see apples, albeit indirectly. There's nothing problematic about this. The indirect realist simply argues that this sort of indirect perception of apples happens even without the visor and its screen.

On direct perception of mental phenomena:

Despite your previous objections to the language, it is perfectly ordinary and correct to say that schizophrenics see and hear things when they hallucinate. The things they see and hear are mental phenomena, not nothing — else there would be no distinction between hallucinating something and not hallucinating anything, or between a visual hallucination and an auditory hallucination, or between a visual hallucination of one thing and a visual hallucination of another thing. This sense of seeing and hearing things also occurs during "veridical" perception, and it is only in virtue of this that we see and hear objects in the world — e.g. if there's damage in the visual and auditory cortexes but otherwise functional eyes and ears then we don't see or hear anything. -

NOS4A2

10.2k

NOS4A2

10.2k

Individuals have different bodies and never occupy the same position in space and time. One might have degeneration of the retina and so is unable to interact with the environment the same as someone who doesn’t. None of this entails some other medium, especially a fuzzy one called “experience”. -

AmadeusD

4.3kat a deeper metaphysical level about what counts as a feature of the world at all. — Esse Quam Videri

AmadeusD

4.3kat a deeper metaphysical level about what counts as a feature of the world at all. — Esse Quam Videri

Yes, that seems right - I did my best to try to say there may be fundamental issues we're not seeing the same way. Thanks for that.

As I understand you, you’re assuming that any property defined in relation to human perceptual capacities collapses into a claim about perception rather than a claim about the world. — Esse Quam Videri

As I see it, it's not an assumption, but a requirement of what we know about our physiology. We are seeing that fact causing different follow-ons, I think, and so my saying this isn't an assumption doesn't work for you - but you calling it one doesn't work for me. I think. At any rate, I cannot conceptually escape this line of thinking without hte handwaving I want to avoid.

On that assumption, statements like “the sky elicits blue-type responses under normal conditions” amount to nothing over and above claims about how humans experience the sky, and so the distinction I’ve been drawing between claims about experience and claims about the world simply disappears. — Esse Quam Videri

Roughly, yes. Its semantically sound to say that the one is "about the sky" and the other about human perception (because they are lol), but there's a ball being hidden imo viz a viz our disagreement. 1. would be more complete as "the sky elicits blue-type responses (in humans) under normal conditions" imo. Those "normal conditions", I take it, are the standard, physiological, interpretive processes involved in the perceptual chain. I can't see what else they are here, which would be relevant to the statement. But i definitely reacted to strongly to clarify properly, so thanks for the charity here.

I reject that assumption... I take ordinary color predicates to work in a similar way: they are world-involving, response-dependent properties, not reports about inner presentation. — Esse Quam Videri

Fair enough. We may not be able to litigate this, but safe to say I can't make sense of the position. It seems like wanting cake and eating it. It seems that we want substance dualism to work there..

So, yes, lol, your final para seems totally on point. Thanks mate - appreciate your elucidations. -

Michael

16.9k

Michael

16.9k

You don't need to believe in non-physical mental phenomena to accept that experience is something the brain does. We see and hear things when the visual and auditory cortices are active, regardless of what things caused this to happen (whether internal to the body or external). If the visual cortex is active in the right kind of way we see colours, even if our eyes are closed and we're in a dark room, e.g. if we have chromesthesia and are listening to music. However you choose to "cash out" these colours they are evidently not the "direct presentation" — in the philosophically relevant sense of the phrase — of something like an apple's surface, and are the medium through which we are made aware that something (probably) exists at a distance (either reflecting light or, for those with chromesthesia, vibrating the air). -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

So in your scenario, it is not possible to assign Fred to one of the populations, but you maintain that the distinction is meaningful. That strikes me as absurd.I disagree with your assertion that we must be able to determine which group someone belongs to for there to be two different groups. — Michael

The same applies to your picture. How could you ever determine that what the chap on the left sees is different to what the chap on the right sees?

This, it seems, might be the core difference between our accounts. You insist that there are private phenomena while apparently agreeing that they make no difference, while I say that since there is no difference, there is no private phenomena. -

Michael

16.9kHow could you ever determine that what the chap on the left sees is different to what the chap on the right sees? — Banno

Michael

16.9kHow could you ever determine that what the chap on the left sees is different to what the chap on the right sees? — Banno

We probably can’t, save for perhaps opening their heads and checking to see which neural correlates are active. It stands to reason that if their visual cortices are behaving differently then they are having different experiences, even if they utter the same words when asked to describe the strawberry. But that's not something we can practically do, especially not in everyday life and especially not if we're not a technologically advanced society.

As a less theoretical example, a language doesn't need to exist for it to be possible that some see the dress to be white and gold and others black and blue. They just either see it to be one set of colours or they don't, regardless of whether or not they can ask each other about it.

It's honestly quite surprising that you of all people are suggesting that something is true only if we can determine that it's true. That's very antirealist of you. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

Interesting. I'm not saying it's not true, but that it's not even true, or false. It's not well formed enough to be true or false. Some strings of words fail to be truth-apt in the first place.It's honestly quite surprising that you of all people are suggesting that something is true only if we can determine that it's true. That's very antirealist of you. — Michael

If <"the blugleberry is foo-coloured" is true if and only if the strawberry is red>, then we have some basis for assigning a truth value.

If there is no public content, the truth condition is not fixed; so unless "the blugleberry is foo-coloured" has some equivalent, such as "the strawberry is red", it has no truth value. After Davidson, we could not recognise "the blugleberry is foo-coloured" as a sentence. A string counts as a sentence only if it can be interpreted. Interpretation requires publicly identifiable conditions of truth. “The blugleberry is foo-coloured” lacks any such conditions. Therefore, it fails prior to truth and falsity: it is not even recognisable as a sentence. -

Richard B

579We probably can’t, save for perhaps opening their heads and checking to see which neural correlates are active. It stands to reason that if their visual cortices are behaving differently then they are having different experiences, even if they utter the same words when asked to describe the strawberry. — Michael

Richard B

579We probably can’t, save for perhaps opening their heads and checking to see which neural correlates are active. It stands to reason that if their visual cortices are behaving differently then they are having different experiences, even if they utter the same words when asked to describe the strawberry. — Michael

I don't think science can offer any assistance in principle. Let me illustrate this with a thought experiment. For simplicity sake, let us assume this world has only two color, red and blue. Let us assume they have established wavelengths of 620 to 750 nm for red and 380 to 500 nm for blue. In the advance civilization, they have the technology to isolate brain state correlates (BSC) in the human brain with great precision. One day they decided to perform an experiment, where two subjects are exposed to two colored swatches (with verified wavelengths). With each exposure, the subject's BSC is recorded. When they exposed the red swatch to S1 they captured a BSC reading of 100, and when exposed to the blue swatch the BSC reading was 200. Interestingly, when they exposed the red swatch to S2 they captured a BSC reading 200, and when exposed to the blue swatch the BSC reading was 100, they complete opposite of S1. In both case, S1 and S2 verbalize the correct color of the swatches. What can the scientists conclude from such experiment? Simply, when these two subjects are exposed to the same colored swatch, there is a different associated BSC. What evidence is there they are experiencing different "private colors"? They are able to make the correct color judgment, so that seems to suggest they are experiencing the same color but just have different BSCs. And if they were experiencing different "private colors" how could we ever assign which "private color" to which BSC? You can't they are private. Would adding more subjects to the experiments help in any way? I do not see how. We can add 10 more and all had the same patterns as S1 and make the same correct color judgments, but in the end, it adds no evidence to what the "private color" is for each subject.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum