-

fdrake

7.2kMarx continues linking value to labour:

fdrake

7.2kMarx continues linking value to labour:

There is, however, something else required beyond the expression of the specific character of the labour of which the value of the linen consists. Human labour power in motion, or human labour, creates value, but is not itself value. It becomes value only in its congealed state, when embodied in the form of some object. In order to express the value of the linen as a congelation of human labour, that value must be expressed as having objective existence, as being a something materially different from the linen itself, and yet a something common to the linen and all other commodities. The problem is already solved.

Mostly repeating things I've already written about. He does however draw attention to a distinction: labour is not value, labour creates value. Labour becomes value only when a commodity is worked on and enters, even figuratively, into an exchange relation with other commodities. The 'congealed state' of labour in the commodity is aligned with its value; and the (socially necessary) duration of that labour imbues that commodity's with value of a given magnitude.

When occupying the position of equivalent in the equation of value, the coat ranks qualitatively as the equal of the linen, as something of the same kind, because it is value. In this position it is a thing in which we see nothing but value, or whose palpable bodily form represents value. Yet the coat itself, the body of the commodity, coat, is a mere use value. A coat as such no more tells us it is value, than does the first piece of linen we take hold of. This shows that when placed in value-relation to the linen, the coat signifies more than when out of that relation, just as many a man strutting about in a gorgeous uniform counts for more than when in mufti.

Again, restating that when a commodity takes a position in the elementary form of value; as either in the relative or equivalent form; only its value is highlighted - all properties irrelevant to this are filtered out.

In the production of the coat, human labour power, in the shape of tailoring, must have been actually expended. Human labour is therefore accumulated in it. In this aspect the coat is a depository of value, but though worn to a thread, it does not let this fact show through. And as equivalent of the linen in the value equation, it exists under this aspect alone, counts therefore as embodied value, as a body that is value. A, for instance, cannot be “your majesty” to B, unless at the same time majesty in B’s eyes assumes the bodily form of A, and, what is more, with every new father of the people, changes its features, hair, and many other things besides.

As before, the physical body of the commodity is subject to a sortal; it counts as its value alone and everything else is filtered out.

Hence, in the value equation, in which the coat is the equivalent of the linen, the coat officiates as the form of value. The value of the commodity linen is expressed by the bodily form of the commodity coat, the value of one by the use value of the other. As a use value, the linen is something palpably different from the coat; as value, it is the same as the coat, and now has the appearance of a coat. Thus the linen acquires a value form different from its physical form. The fact that it is value, is made manifest by its equality with the coat, just as the sheep’s nature of a Christian is shown in his resemblance to the Lamb of God.

If 1 pair of trousers is worth 1 coat, 'coat' serves as the representation of value for the trousers, with a magnitude '1' and ratio to 'pair of trousers' as 1:1. The bodily form of the coat counts as the value of the pair of trousers, thus the trousers become a representation of the value embodied in the coat. More generally, 'x use value 1 is worth y use value 2' has the same structure. Note that only use values can serve as repositories of value.

Marx summarises:

We see, then, all that our analysis of the value of commodities has already told us, is told us by the linen itself, so soon as it comes into communication with another commodity, the coat. Only it betrays its thoughts in that language with which alone it is familiar, the language of commodities. In order to tell us that its own value is created by labour in its abstract character of human labour, it says that the coat, in so far as it is worth as much as the linen, and therefore is value, consists of the same labour as the linen. In order to inform us that its sublime reality as value is not the same as its buckram body, it says that value has the appearance of a coat, and consequently that so far as the linen is value, it and the coat are as like as two peas. We may here remark, that the language of commodities has, besides Hebrew, many other more or less correct dialects. The German “Wertsein,” to be worth, for instance, expresses in a less striking manner than the Romance verbs “valere,” “valer,” “valoir,” that the equating of commodity B to commodity A, is commodity A’s own mode of expressing its value. Paris vaut bien une messe. [Paris is certainly worth a mass]

and concludes the subsection:

By means, therefore, of the value-relation expressed in our equation, the bodily form of commodity B becomes the value form of commodity A, or the body of commodity B acts as a mirror to the value of commodity A.[19] By putting itself in relation with commodity B, as value in propriâ personâ, as the matter of which human labour is made up, the commodity A converts the value in use, B, into the substance in which to express its, A’s, own value. The value of A, thus expressed in the use value of B, has taken the form of relative value. -

fdrake

7.2kSubsection summary: the relative form of value, nature and import of this form.

fdrake

7.2kSubsection summary: the relative form of value, nature and import of this form.

If x use value 1 is worth y use value 2, x use value 1 stands in the relative form of value to y use value 2 which is the equivalent. use value 2, when envisioned or actually put into this relation, becomes the value form of use value 1; the means of the representation of the value in 1. Prior to this, the two are rendered equivalent in their reduction to human labour in the abstract - as socially useful products of labour power -, and the (ratio of) socially necessary durations of the labour gives the magnitudes x and y. -

fdrake

7.2kSubsubsection B: Quantitative determination of Relative value

fdrake

7.2kSubsubsection B: Quantitative determination of Relative value

This section largely consists of Marx specifying the algebraic structure that holds of the relative form.

Marx first summarises points he has made before:

Every commodity, whose value it is intended to express, is a useful object of given quantity, as 15 bushels of corn, or 100 lbs of coffee. And a given quantity of any commodity contains a definite quantity of human labour. The value form must therefore not only express value generally, but also value in definite quantity. Therefore, in the value relation of commodity A to commodity B, of the linen to the coat, not only is the latter, as value in general, made the equal in quality of the linen, but a definite quantity of coat (1 coat) is made the equivalent of a definite quantity (20 yards) of linen.

(1) Value only applies to use values.

(2)(a) The value form is partly what renders use values as commensurable products of human labour.

(b) The value form also gives use values their definite magnitudes of value.

The equation, 20 yards of linen = 1 coat, or 20 yards of linen are worth one coat, implies that the same quantity of value substance (congealed labour) is embodied in both; that the two commodities have each cost the same amount of labour of the same quantity of labour time. But the labour time necessary for the production of 20 yards of linen or 1 coat varies with every change in the productiveness of weaving or tailoring. We have now to consider the influence of such changes on the quantitative aspect of the relative expression of value.

It's pretty clear to see that, say, 1 pair of trousers has less value than 2 pairs of trousers, so Marx expands on the various operations that respect the 'is worth' relation T and the relationship between socially necessary labour time and value.

I. Let the value of the linen vary,[20] that of the coat remaining constant. If, say in consequence of the exhaustion of flax-growing soil, the labour time necessary for the production of the linen be doubled, the value of the linen will also be doubled. Instead of the equation, 20 yards of linen = 1 coat, we should have 20 yards of linen = 2 coats, since 1 coat would now contain only half the labour time embodied in 20 yards of linen. If, on the other hand, in consequence, say, of improved looms, this labour time be reduced by one-half, the value of the linen would fall by one-half. Consequently, we should have 20 yards of linen = ½ coat. The relative value of commodity A, i.e., its value expressed in commodity B, rises and falls directly as the value of A, the value of B being supposed constant

Summarising: value is proportional to socially necessary labour time. Assuming that the labour time for y does not change, this means that if the labour time for x increases, and we have xTy, the amount of y which x is worth increases. Inversely if the labour time for x decreases, the the amount of y which is worth x decreases.

Assume 'a x is worth b y', that x stands in the relative form to y which is its equivalent. Then: let V represent a commodity's value. If V(x) = V(y), then V(x) halves, we have 2V(x)=V(y). Inversely if V(x) doubles, we have V(x)=2V(y). As a consequence of the first, we have 2a x is worth b y. As a consequence of the second, we have a x is worth 2b y.

II. Let the value of the linen remain constant, while the value of the coat varies. If, under these circumstances, in consequence, for instance, of a poor crop of wool, the labour time necessary for the production of a coat becomes doubled, we have instead of 20 yards of linen = 1 coat, 20 yards of linen = ½ coat. If, on the other hand, the value of the coat sinks by one-half, then 20 yards of linen = 2 coats. Hence, if the value of commodity A remain constant, its relative value expressed in commodity B rises and falls inversely as the value of B.

This paragraph applies the same reasoning to the equivalent. Here we have V(x)=V(y) if V(y) halves, then V(x)=2V(y), if V(y) doubles, we have 2V(x)=V(y).

Marx notes that this comes down the the symmetry of T, that relative and equivalent forms depend solely on 'accidental position' in T:

If we compare the different cases in I and II, we see that the same change of magnitude in relative value may arise from totally opposite causes. Thus, the equation, 20 yards of linen = 1 coat, becomes 20 yards of linen = 2 coats, either, because the value of the linen has doubled, or because the value of the coat has fallen by one-half; and it becomes 20 yards of linen = ½ coat, either, because the value of the linen has fallen by one-half, or because the value of the coat has doubled.

then continues:

III. Let the quantities of labour time respectively necessary for the production of the linen and the coat vary simultaneously in the same direction and in the same proportion. In this case 20 yards of linen continue equal to 1 coat, however much their values may have altered. Their change of value is seen as soon as they are compared with a third commodity, whose value has remained constant. If the values of all commodities rose or fell simultaneously, and in the same proportion, their relative values would remain unaltered. Their real change of value would appear from the diminished or increased quantity of commodities produced in a given time.

If V(x)=V(y) and V(x) and V(y) are both doubled, then V(x)=V(y) still, only the relative values of x and y to other commodities change.

IV. The labour time respectively necessary for the production of the linen and the coat, and therefore the value of these commodities may simultaneously vary in the same direction, but at unequal rates or in opposite directions, or in other ways. The effect of all these possible different variations, on the relative value of a commodity, may be deduced from the results of I, II, and III.

IE, if V(x)=V(y) and V(x) is scaled by a/b, aV(x)=bV(y).

Focussing in on point III, Marx adds:

Thus real changes in the magnitude of value are neither unequivocally nor exhaustively reflected in their relative expression, that is, in the equation expressing the magnitude of relative value. The relative value of a commodity may vary, although its value remains constant. Its relative value may remain constant, although its value varies; and finally, simultaneous variations in the magnitude of value and in that of its relative expression by no means necessarily correspond in amount.[21]

(1) The relative value of x to y doesn't completely characterise the value of x.

(2) Changes in the relative value of x to y don't completely characterise changes in value more generally.

(3) x can remain worth y even under incredibly chaotic conditions of exchange.

The incompletion of this value form, and its reference to the values of other commodities not in 'x is worth y' prefigure later stages of the account; the expanded/total and money forms of value.

Summarising the properties of V we will have that:

(A) V(x+y)=V(x)+V(y)

(B) V(Ax)=AV(x)

(C) V(x-y)=V(x)-V(y)

incidentally from (3) we have that V(0)=V(x-x)=V(x)-V(x)=0. Nothing is worth nothing. Note that these correspond neatly to the algebra of commodities I set up already:

Where x,y,a,b are commodities in the sense I developed here, and A is a number which respects the amount structure of x and y.

(1) V(x+y)=V(x)+V(y) <=> [xTy & aTb => (x+a)T(y+b)]

(2) V(Ax)=AV(x) <=> [xTy <=> (Ax)T(Ax)]

(3) V(x-y)=V(x)-V(y) <=> [xTy <=> (x-a)T(y-a)]

(4) [V(x)=V(y) <=> V(y)=V(x) ]<=> T is symmetric.

(5) V(x)=V(x) <=> T is reflexive.

V(x) should be seen as taking values in with the continuous amount structure. That is:

and properties A,B,C establish that it's a homomorphism. Note that it is a surjective homomorphism because V(x) and V(y) can be the same without x=y. This is just to say that different amounts of different commodities can still be worth the same.

Also, this isn't yet an ordered field because there are no negative values - developing those will come later when dealing with debt and money of account. -

fdrake

7.2kAnother thing to note is that the elementary form of value alone doesn't necessarily obey the following constraint:

fdrake

7.2kAnother thing to note is that the elementary form of value alone doesn't necessarily obey the following constraint:

V(x)=V(y) <=> xTy

With this assumption (and A->C) (1)->(5) can be derived.

(1) Assume xTy, then iff V(x) = V(y) and V(a)=V(b), iff V(x)+V(a)=V(y)+V(b), iff V(x+a)=V(y+b) iff (x+a)T(y+b)

(2) Assume xTy, then(Ax)T(Ay), then V(Ax)=V(Ay) so AV(x)=AV(y). Similarly AxTAy iff V(Ax)=V(Ay)=>V(x)=V(y)=>xTy

(3) Assume xTy, then (x-a)T(y-b) with aTb, then V(a)=V(b) and V(x-a)=V(y-b) then V(x)-V(a)=V(y)-V(b) so V(x)=V(y), reverse implications.

(4) xTy <=> V(x)=V(y) <=> yTx <=> V(y)=V(x)

(5) xTx <=> V(x)=V(x) -

frank

19kNumbers and math have roots in trade, so describing it in the language of math creates an image if the child rising up to reduce the parent.

frank

19kNumbers and math have roots in trade, so describing it in the language of math creates an image if the child rising up to reduce the parent.

Weatherford describes markets in Mali where the merchants have no formal education and cant read, but theyre experts at negotiation and currency exchange. They use a settled sign language where spoken language is a barrier. Math as a common language. -

Moliere

6.5kI'd also note that not-for-profit is something of a in-name-only -- I'd say that the general critique of capital applies just as well to non-profit orgs in that they produce a commodity and sell it at a higher price than the use-value which goes into making said commodity; the individuals in charge of non-profit orgs do not make as much as their counterparts, but the motive remains the same: increase revenue greater than expenditures.

Moliere

6.5kI'd also note that not-for-profit is something of a in-name-only -- I'd say that the general critique of capital applies just as well to non-profit orgs in that they produce a commodity and sell it at a higher price than the use-value which goes into making said commodity; the individuals in charge of non-profit orgs do not make as much as their counterparts, but the motive remains the same: increase revenue greater than expenditures.

This is just the totalising nature of capital.

Not that non-profit orgs don't do good just because of this. They often do (as do for-profit orgs, for that matter) -- I just mean to point out that they are still a part of the larger sociopolitical system of capital. -

fdrake

7.2k

fdrake

7.2k

I usually operate under the assumption that responses to a thread try to be on topic. Thing is, I can't tell because you never spend enough words detailing what you think. And every other time I've asked you for more words or clearer writing you ran away.

Think the observation is good. Some charities are in name only. I had in mind things like independent soup kitchens, urban foragers, food banks and volunteer teachers/counsellors. -

Moliere

6.5kThink the observation is good. Some charities are in name only. I had in mind things like independent soup kitchens, urban foragers, food banks and volunteer teachers/counsellors. — fdrake

Moliere

6.5kThink the observation is good. Some charities are in name only. I had in mind things like independent soup kitchens, urban foragers, food banks and volunteer teachers/counsellors. — fdrake

I guess it depends on the specifics. . . but the general form of capital seems to perpetuate itself, at least in my experience. Though I'll admit I'm generalizing from my own experiences here, so maybe there are some counter-examples that I haven't run across.

I used to work for a union, and even there membership was seen as a revenue base. It's not like people who worked for the union didn't care about working class struggles or anything like that. In fact, the money was chased because it was required in order to make wins and service the membership of the union. Rather, even in spite of all the best intentions the general sociopolitical structure was such that that you had to care about things like a capitalist does.

It's in that sense that I mean -- so even if it's not in-name-only, ala a corrupt organization, but even a well-run organization -- the form of capital imposes itself on the org. -

Moliere

6.5kYes, exactly. It makes perfect sense. I'm not trying to disparage the practice of what works -- only to highlight how totalising capital really is, and also highlight that though the model is of an English factory worker in the 1800's it is a pretty generally applicable model that applies to commodities as ephemeral as "wins"

Moliere

6.5kYes, exactly. It makes perfect sense. I'm not trying to disparage the practice of what works -- only to highlight how totalising capital really is, and also highlight that though the model is of an English factory worker in the 1800's it is a pretty generally applicable model that applies to commodities as ephemeral as "wins" -

fdrake

7.2k

fdrake

7.2k

(1) He already does look at it mathematically. See recent post going through points I-III in the relative form, Marx is explicitly talking about how operations on labour time respect the 'is worth' relation. I'm mostly spelling things out explicitly that Marx already put in there. Another good example is his discussion over whether 'is worth' is reflexive ('x is worth x').

(2) It clarifies things, like why the elementary form of value doesn't have to preserve value magnitudes in trades, a puzzle Marx leaves for us. Also it shows how enforcing that trades preserve value magnitudes engenders a structural symmetry between values and commodities. These are just two examples.

(3) It's interesting to me. -

frank

19kSo it's native to Marx, it clarifies, brings explicitness, and fills in blanks left by Marx (which would serve to fortify?)

frank

19kSo it's native to Marx, it clarifies, brings explicitness, and fills in blanks left by Marx (which would serve to fortify?)

Does it also facilitate prediction? I think that's one reason economics at large is mathemetized. Failures in mathematical models lead to revision. -

fdrake

7.2k

fdrake

7.2k

I don't think any of the maths I've done so far makes predictions as such, though there have been a few nice theoretical results. One is that a system of exchange maintains the magnitude of value through trades if and only if you can't trade nothing for something. Soon there'll be a very easy demonstration that having strictly more stuff means you have strictly more value.

So spelling things out with mathematical structures like this isn't so much making novel empirical predictions, it instead should be judged on how well it ties lots of things which are expected to be true together in a nice way. In terms of faithfulness to Marx's ideas, using them should agree with how Marx uses them wherever possible.

That attempt at remaining in good faith is one of the reasons I spent so long trying to understand how subtraction works for commodities; because we know that goods can be removed from an exchange, but also that values are greater than or equal to 0 (since they're proportional to time). So while you don't see an account of 'commodity subtraction' in the book, I've used it to produce things which are in agreement with Marx' account. -

fdrake

7.2kMarx moves onto discussing the equivalent form more deeply.

fdrake

7.2kMarx moves onto discussing the equivalent form more deeply.

Subsection 3: 3. The Equivalent form of value

Marx begins by restating the duality between the relative and equivalent forms:

We have seen that commodity A (the linen), by expressing its value in the use value of a commodity differing in kind (the coat), at the same time impresses upon the latter a specific form of value, namely that of the equivalent.

and draws out some of the implications about the equivalent form from the previous section explicitly:

The commodity linen manifests its quality of having a value by the fact that the coat, without having assumed a value form different from its bodily form, is equated to the linen. The fact that the latter therefore has a value is expressed by saying that the coat is directly exchangeable with it. Therefore, when we say that a commodity is in the equivalent form, we express the fact that it is directly exchangeable with other commodities.

Bolded bit: this is saying that 'x use value 1 is worth y use value 2' has the feature that the relative value of x use value 1 is expressed as y use value 2: that the value, despite being strictly social, is an evaluation of x use value 1 in terms of the concrete amount y of use value 2. This only occurs because x use value 1 is exchangeable for y use value 2.

When one commodity, such as a coat, serves as the equivalent of another, such as linen, and coats consequently acquire the characteristic property of being directly exchangeable with linen, we are far from knowing in what proportion the two are exchangeable.

Marx restates that the exchangeability of x use value 1 with y use value 2 as a determination of numerically identical values only makes sense upon the assumption that use value 1 is exchangeable with use value 2; this is because the numerical equivalence between them has to arise from somewhere; that they are exchangeable does not say how much one exchanges for the other.

I think a decent analogy here is blowing up a balloon. The points on the surface of a balloon are always connected, and if we say that two points on its surface are connected they are commensurate, then every point on the balloon becomes commensurate with every other by mere fact that it is a smooth, unitary surface without holes. However, that the balloon's points are connected/commensurate with each other tells us nothing about the distance of pairs of points; blowing up the balloon allows the specific distance of paths on the balloon surface to change without changing the commensuration which ensures the existence of those paths. The balloon itself is the form of value, whose magnitudes are determined by an external process.

The value of the linen being given in magnitude, that proportion depends on the value of the coat. Whether the coat serves as the equivalent and the linen as relative value, or the linen as the equivalent and the coat as relative value, the magnitude of the coat’s value is determined, independently of its value form, by the labour time necessary for its production.

Bolded bit is important. It characterises the value form - that is, at the minute, the duality of relative and equivalent, as the real abstraction driving the commensuration of commodities in definite amounts, whose definite amounts are given through the ratio of socially necessary labour times.

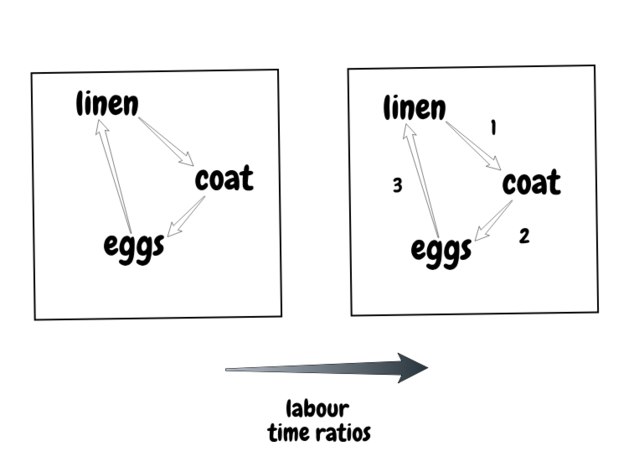

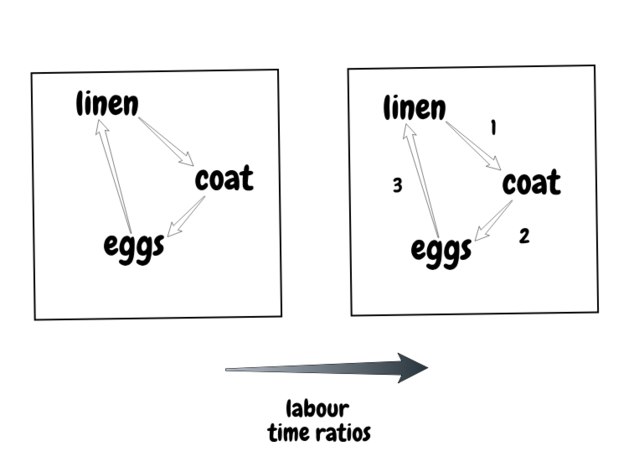

The balloon analogy is actually mathematically quite literal if we consider the relation T from before. The commensuration of entities is equivalent to the ability to exchange one type for another type; the amounts are given by the application of socially necessary labour time ratios. So the existence of a path between two commodity types is their commensuration, the weighting of that path with an exchange ratio determined by the ratio of labour times is the application of a magnitude. (Ignore that the arrows are one way here, the relation is really symmetric)

But whenever the coat assumes in the equation of value, the position of equivalent, its value acquires no quantitative expression; on the contrary, the commodity coat now figures only as a definite quantity of some article.

Marx gives us an example:

For instance, 40 yards of linen are worth – what? 2 coats. Because the commodity coat here plays the part of equivalent, because the use-value coat, as opposed to the linen, figures as an embodiment of value, therefore a definite number of coats suffices to express the definite quantity of value in the linen. Two coats may therefore express the quantity of value of 40 yards of linen, but they can never express the quantity of their own value. A superficial observation of this fact, namely, that in the equation of value, the equivalent figures exclusively as a simple quantity of some article, of some use value, has misled Bailey, as also many others, both before and after him, into seeing, in the expression of value, merely a quantitative relation. The truth being, that when a commodity acts as equivalent, no quantitative determination of its value is expressed.

To sum up, this characterises the relationship of relative and equivalent as:

(1) When a commodity assumes the relative form, and thus has an equivalent, the two must be exchangeable in order for one to be valued in terms of the other.

(2a) When we say 'x is worth y', this takes the value of x and represents it in terms of its exchange ratio with a definite amount of use value y.

(2b) 2a implies that y when serving as the equivalent has no expression of its value - IE, that the value form of dual relative and equivalents expresses solely the value of that commodity occupying the relative spot.

(2c) Nevertheless, the 'accidental position' of relative and equivalent can be reversed and we obtain a value expression for y in terms of x. -

andrewk

2.1kI have only read part of this, and even that has raised some interesting questions for me.

andrewk

2.1kI have only read part of this, and even that has raised some interesting questions for me.

(1). Marx talks about divergence of price from value. Does that mean that he thinks the two are different? I find it hard to define value without using price. A topical and handy reference point is the definition of 'fair value' under the IFRS and GAAP accounting standards, which identifies fair value broadly as:

"the price that would be expected by a willing, but not overeager, buyer to a willing, but not overeager, seller to transfer an asset or liability, after taking all available information into account."

In finance there are ways of calculating value that make no direct reference to buyers and sellers - two examples of which are discounted cash flow and arbitrage pricing. This can have two purposes depending on context:

- for an item that the holder intends to hold to maturity (or until consumed or worn-out, in the case of a physical item), it is the value to that holder of the item. That value can, and does, vary significantly between holders. An oil rig has no value to me other than what I might be able to sell it for (which would not be much, since I don't have the right contacts) but would have great value to an oil company, as it will be a source of future profit.

- for an item that is likely to be sold, the calculation serves as an estimate of what sale price might be able to be achieved. For this to work it must be the case that most other market participants use the same general valuation approach as I do. This becomes particularly interesting in periods when major changes in valuation methods are being adopted, as has been the case in finance since the 2008-09 economic crisis. At such times big differences can arise in valuations made by different market participants.

(2). The part of it that is most interesting to me is the attempt to equate value of an item to the minimal hours of labour needed to produce it. This strikes me as laudable, if it can be made to work.

I wonder if it can cope with trading based on comparative advantage though. The classic example is islands A and B that need primary commodities C and D to survive. Island A can produce both C and D for fewer hours labour than B requires - because of geographic conditions, climate, tools, education of population, or other structural differences. But rather than A each making all its own stuff and A being much more prosperous than B, both islands benefit from B making the item for which A has the lower comparative advantage over B (say it's D), and then trading some of its D for C produced by A.

Since both islands benefit from the trade, I wonder how this can be accommodated into Marx's framework that regards value of an item as being somehow universal at each point in time.

A-ers will place a higher value on item D (measured in units of item C) than B-ers do. When A trades it acquires some D at a price (in units of C) that is lower than the value A places on it.

Conversely, from B's point of view, it sells some D at a price (in units of C) that is higher than the value B places on it.

I supposed we could say that each commodity has three values:

1. the value A puts on it, in terms of the other commodity, if no trade is occurring. This is based on the relative time costs for production in A

2. the value B puts on it, in terms of the other commodity, if no trade is occurring. This is based on the relative time costs for production in B

3. the exchange rate between the two commodities that is used in trade. This will be between the above two numbers, otherwise the trade will not occur because it will not be beneficial for one party.

It's made a bit tricky in that, while 1 and 2 may be stable, 3 can be any number between 1 and 2 and will depend on the relative skill of the two nations' trade negotiators. So while 1 and 2 seem more like the notion of an observer-independent value - unrelated to price, 3 is completely dependent on market negotiations.

I had some other thoughts, but this post is already too long. -

fdrake

7.2k

fdrake

7.2k

Responding to (2) first:

There are scenarios where the assumption that the value of a commodity equals the socially necessary labour time doesn't hold. I wrote about this by introducing the distinction between productive equilibrium and productive disequilibrium.

(1) Productive equilibrium is the state of a distribution of labour times for a commodity when its minimum equals its mode.

(2) Productive disequilibrium is the state of a distribution of labour times for a commodity where its mode is greater than its minimum.

Under these assumptions, the paired island economy is in a state of productive disequilibrium because each produces C and D with different socially necessary labour times. The distribution is also bimodal as there are two local maxima; corresponding to the labour time of A producing C and B producing C. The same holds for A producing D and B producing D.

I think this example is a bit of a toy problem and doesn't really reflect the conditions in the economy at large, but I think it's worthwhile seeing if analysing things in terms of their labour times producing a mutual advantage through exchange.

If we assume that we're analysing per day per person, we have 24 hours of labour time to spend on producing C and D. This means that there is a trade off in the productions of C and D for both islands, and both islands have a maximum amount of each they could produce. So we end up in the situation where a proportion of 24 hours is spent producing C and a proportion is spend producing D. This holds for both A and B, and both have different productivities for C and D. This gives the equations that govern the total daily production as:

Production on A = x1*p1 C + y1*(1-p1) D

Production on B = x2*p2 C + y2*(1-p2)D

where p1 is the fraction of hours spent on A producing C, x1 and y1 are the maximal per day productivities of C and D respectively on A. Analogously for B.

Assume wlog that x1>y1 and y2>x2 the sum of Production A and B is maximised in terms of the number of goods at:

x1C+y2D

under the assumption that the global maximum is the sum of the two local maxima.

So A is producing x1C and B is producing y2D. The spending strategies don't matter as both A and B are producing their maximal amount per unit time - assuming free trade both obtain more per day, as is classically concluded.

I would be extremely surprised if Marx wasn't aware of these ideas and I'm sure he thought of the two islands example when setting up his theory of value; as he frequently cites the originator of the example, Ricardo, and also believes that the division of labour increases overall productivity through specialisation (IIRC anyway, it's been a while since I read that bit).

I also don't really trust the example. Hand waving at 'free trade' doesn't work much for me, it could be the case that B simply wasn't productive enough to be of use to A, or that the exchange ratios are completely crazy.

Honing in on this - if we have it that x1:y2 is tiny, B might not be able to obtain enough of C or conversely for y2:x1 tiny A might not be able to obtain enough of D. The same could be said for any mechanism which fixes the exchange ratios, not necessarily just labour time. There have to be some regularity conditions on productivity and exchange for 'free trade' to be able to provide both islands with enough.

So if we assume that A produces m1+n1 of C, where m1 is the minimal amount of C which A needs, and that B produces m2+n2 of D, where m1 is the minimal amount of D which B needs, this leaves n1 to be traded for n2. We also have to assume, then, that n1 is enough of C for B and that n2 is enough of D for A. It could be that n1=0 and then both islands are screwed, and this is fully consistent with the scenario and 'maximal productivity' logic, even when, say, y1 is equal to x1. -

Benkei

8.1kIn finance there are ways of calculating value that make no direct reference to buyers and sellers - two examples of which are discounted cash flow and arbitrage pricing. — andrewk

Benkei

8.1kIn finance there are ways of calculating value that make no direct reference to buyers and sellers - two examples of which are discounted cash flow and arbitrage pricing. — andrewk

I don't agree with the discounted cash flow not having any reference to buyers and sellers. The discount curve you're going to use is an interest benchmark in most cases, which in turn is based on actual transaction/quote data (spot and forward). I'm on the fence about APT. Even arbitrage pricing ultimately has to take into account the effects the macro-economic factors have on cost, pricing and return and therefore what buyers and sellers can afford to do and not do. -

andrewk

2.1k

andrewk

2.1k

You're right. I thought exactly that as I wrote it and then - arrogantly - thought 'nah, this is a philosophy forum, not a finance one - nobody will pick me up on it'. I was wrong!I don't agree with the discounted cash flow not having any reference to buyers and sellers. The discount curve you're going to use is an interest benchmark in most cases, which in turn is based on actual transaction/quote data (spot and forward). — Benkei

This is another case of me being lazy. I didn't mean APT (Arbitrage Pricing Theory) but arbitrage-free pricing of derivatives (Black-Scholes and the like), but I forgot the 'free' bit and found it easier to just write 'arbitrage pricing'. Arbitrage-free pricing of course still depends on market prices because it relates the value of a derivative to the value of the underlying asset, but what I had in mind was that the relationship between the prices of derivative and underlying asset doesn't depend on market sentiment. Of course it does, at least at second order, because interest rates and implied volatilities come into it, at which point your first objection comes into operation.I'm on the fence about APT. — Benkei

Perhaps a better way to characterise the distinction I think I was trying to make is as model-based prices versus observed prices. The latter assigns the value of item A on the most recent prices at which such items were seen to be sold. The former seeks to work out the benefit to the prospective holder of purchasing the asset, in terms of ultimate profit through holding to maturity (leaving aside early exercise for American options and the like) without making any assumptions about what the item could be re-sold for. -

frank

19kJust a stray note about value: value takes shape in a particular "cultural configuration." A single market can span diverse configurations, which means participants may have little comprehension of one another's uses.

frank

19kJust a stray note about value: value takes shape in a particular "cultural configuration." A single market can span diverse configurations, which means participants may have little comprehension of one another's uses.

Money makes this kind of cultural bridge possible.

"Cultural configuration" is anthropologist Ruth Benedict's terminology. -

frank

19kSorry. I guess I'm not sure which part to explain because I dont know where our interests intersect.

frank

19kSorry. I guess I'm not sure which part to explain because I dont know where our interests intersect.

What's fascinating me is the similarities between money and math. They're both about abstraction. In the same way "2" becomes divorced from any particular couple, currency is divorced from any particular way of assessing value. Money and math are transcultural languages in much the same way.

I'm curious to know if Marx realized this.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- 'Quantum Jumping', 'Multiverse' Theory, and explaining experiential phenomena in "lower-level terms"

- A Correct Formulation of Sense-Datum Theory in First-Order Logic

- Possible revival of logical positivism via simulated universe theory.

- Myth-Busting Marx - Fromm on Marx and Critique of the Gotha Programme

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum