-

fdrake

7.2k

fdrake

7.2k

The analysis begins with the trade of one item for another. The items which are traded are called commodities. Commodities have a technical sense here, as they are items which have a component of 'use value' - the utility they serve, like wearing clothes or eating food - and 'exchange value' - the value they take in exchange.

In exchange, the value of one item, say 1 yard of linen, is equated to another item, 1 pair of trousers. If we write "1 yard of linen is worth 1 pair of trousers', Marx calls the first bit the 'relative form', here the 1 yard of linen, and the second bit the 'equivalent form', here 1 pair of trousers.

Towards the start of the thread; when I went through a very dense summary of my understanding of Marx's value theory; you'll have seen me talking about the expanded form of value and the money commodity.

The expanded form of value for, say, for the 1 yard of linen, is the set of all commodities which could be exchanged for 1 yard of linen as an exchange of equivalently valued goods.

The money commodity, Marx's example (and he stresses that it's just an example), is gold. Gold functions as the money commodity by serving as a universal equivalent. A universal equivalent is the commodity using which the values of all other commodities are expressed. So instead of say:

1 yard of linen is worth 1 pair of trousers

1 yard of linen is worth 2 coats

1 yard of linen is worth 900 eggs

we end up with

1 yard of linen is worth 0.5g of gold, say

and 1 pair of trousers is then worth 0.5g of gold

and 900 eggs is worth 0.5g of gold.

...

and so on for all commodities which have the same value as 0.5g of gold

The social function of currency is to serve as a representative of the set of commodities which have that value. Any fiat or digital currency functions as a universal equivalent because it maintains the social function of money, even though it is no longer redeemable as a specific commodity through an institution (like the Bank of England). A token representation of value (currency) functions in just the same way as a universal equivalent (but of course it will differ in laws surrounding it and how it may be manipulated).

When we end up with a privileged representation of a set of commodities of equivalent value, we have a money commodity. When that's abstracted to a fiat currency, it's the same mechanism with different legal and institutional backing/enforcement required.

The reason I haven't addressed money commodities or fiat currencies (or even the expanded form of value and the universal equivalent) with my more detailed exegesis is just because they come later in the chapter. -

frank

19k1 yard of linen is worth 1 pair of trousers

frank

19k1 yard of linen is worth 1 pair of trousers

1 yard of linen is worth 2 coats

1 yard of linen is worth 900 eggs

we end up with

1 yard of linen is worth 0.5g of gold, say

and 1 pair of trousers is then worth 0.5g of gold

and 900 eggs is worth 0.5g of gold. — fdrake

This is not how a free market works, so what world is being analyzed? That was my question. In non-free markets, exchange is regulated by officials.

Are you saying that it will become clear down the line? -

fdrake

7.2k

fdrake

7.2k

The stakes in Marx's value theory are how do commodities obtain their values in a capitalist society. He's especially interested in how money gets its value - not just that it has a value, but also the magnitude of its value.

The book starts off analysing the conceptual structure of exchange - his value theory -, he relates it to work -the labour theory of value and of labour in capitalist production as value productive -, only after touching on labour as value-productive does he start analysing exchange networks (the next full chapter is on the circulation of commodities and the circulation of money).

Edit: It's also really really necessary to keep in mind that when Marx talks about value, he isn't talking just about price. Pricing mechanisms are a related but distinct topic of inquiry. EG, for Marx, things like unprocessed oil reserves or unworked land don't have a value even though they can be bought for money. -

andrewk

2.1kThinking about this a bit more, they don't need to be separate economies to raise challenging questions. Say Lakshmi can produce wedding cakes or funeral cakes at the rate of ten per day, but the best anybody else can do is five per day, because Lakshmi possesses unique skills, and the demand is for ten wedding cakes and ten funeral cakes per day. Then how do we work out the labour-value of wedding and funeral cakes? It seems unrealistically optimistic to me to say to say they are both 0.1 day, since the demand cannot be met at that price. But it also seems unrealistically pessimistic to say the prices are 0.2 day, since the demand can be met at a lower price than that.

andrewk

2.1kThinking about this a bit more, they don't need to be separate economies to raise challenging questions. Say Lakshmi can produce wedding cakes or funeral cakes at the rate of ten per day, but the best anybody else can do is five per day, because Lakshmi possesses unique skills, and the demand is for ten wedding cakes and ten funeral cakes per day. Then how do we work out the labour-value of wedding and funeral cakes? It seems unrealistically optimistic to me to say to say they are both 0.1 day, since the demand cannot be met at that price. But it also seems unrealistically pessimistic to say the prices are 0.2 day, since the demand can be met at a lower price than that.

I wonder how Marx would address this. The labour-value of each seems to vary according to how much of her time Lakshmi spends on Wedding cakes. -

fdrake

7.2k

fdrake

7.2k

I don't think this is too different for Marx from the two islands example. We're in a state of transition between two socially necessary labour times - when the minimum labour time is not equal to the modal one, so the comparative advantage Lakshmi has can be described by her unique ability for more productive labour of the same commodity. She can produce the same good quicker than the norm, so she produces more value per hour of her labour regardless of how long she spends doing it on any day. The 'normal' conditions of production set the value even in a period of transition to a new normal; so any averaging or other statistical operations that summarise the value are to be done over the productive processes, rather than the produced goods.

I'm also pretty sure that for Marx supply and demand influence the price of commodities but not necessarily their value. Supply can be linked to productivity a little; insofar as if it takes x amount of time to produce y of the good, the yearly rate of production, say, could be lower than the per day on-season rate due to seasonality or other constraints. So a 'scarce' commodity could be scarce because it has a very low rate of production. Supply and demand will (ideally) influence how much of a commodity is produced, but not the time required for the production of a single unit of that commodity. In this way, the accumulated value of all commodities in a productive network tracks the extent and efficiency of automation and the (an) average of the costs for an hour of labour closer than it tracks changes in demand or supply of any group of commodities made in that productive network.

There's little reference to supply and demand in the first chapter of the book, where Marx is detailing the fundamental parts of his theory of value. He deals with the relationship between valueless goods; like non-commodities which are that in virtue of no physical form, or unprocessed assets; and those with value much later in the work, specifically in volume 3 in terms of fictitious capital. -

fdrake

7.2kcontinuing developing the account of the equivalent form of value.

fdrake

7.2kcontinuing developing the account of the equivalent form of value.

The first peculiarity that strikes us, in considering the form of the equivalent, is this: use value becomes the form of manifestation, the phenomenal form of its opposite, value.

This references that when 'x is worth y', the way the value of x is expressed is as a specific quantity of the use value y. This means, when entering into exchange, use values are the medium for the expression of value through the quantity of the use value.

The bodily form of the commodity becomes its value form. But, mark well, that this quid pro quo exists in the case of any commodity B, only when some other commodity A enters into a value relation with it, and then only within the limits of this relation.

this is to say that quantities of use values operate as the form of manifestation for value only when considering a commodity under the aspect of exchange; that is, only when considering them insofar as they are subjected to the value form.

Since no commodity can stand in the relation of equivalent to itself, and thus turn its own bodily shape into the expression of its own value, every commodity is compelled to choose some other commodity for its equivalent, and to accept the use value, that is to say, the bodily shape of that other commodity as the form of its own value.

This is a reiteration with a different emphasis. Saying 'x is worth x' says nothing about the value of x, x is always worth itself. So if we want to ascertain the value of x, it needs to be compared to an amount of a y. What determines the amount of y is the abstract labour embodied in the amount of x.

Nevertheless, I have argued elsewhere that so long as we are considering that a commodity has already been brought into the exchange relation with another commodity, we can assume its value has found an expression and treat 'x is worth x' as a harmless tautology rather than a breakdown of the relative and equivalent form. -

fdrake

7.2kMarx analogises value to weight:

fdrake

7.2kMarx analogises value to weight:

One of the measures that we apply to commodities as material substances, as use values, will serve to illustrate this point. A sugar-loaf being a body, is heavy, and therefore has weight: but we can neither see nor touch this weight. We then take various pieces of iron, whose weight has been determined beforehand. The iron, as iron, is no more the form of manifestation of weight, than is the sugar-loaf. Nevertheless, in order to express the sugar-loaf as so much weight, we put it into a weight-relation with the iron. In this relation, the iron officiates as a body representing nothing but weight. A certain quantity of iron therefore serves as the measure of the weight of the sugar, and represents, in relation to the sugar-loaf, weight embodied, the form of manifestation of weight. This part is played by the iron only within this relation, into which the sugar or any other body, whose weight has to be determined, enters with the iron. Were they not both heavy, they could not enter into this relation, and the one could therefore not serve as the expression of the weight of the other. When we throw both into the scales, we see in reality, that as weight they are both the same, and that, therefore, when taken in proper proportions, they have the same weight. Just as the substance iron, as a measure of weight, represents in relation to the sugar-loaf weight alone, so, in our expression of value, the material object, coat, in relation to the linen, represents value alone.

which is similar in function to the earlier analogies of chemical formulae and area, and like area exhibits a property with magnitude. However, unlike weight, value is not imbued upon the commodity through its physical constitution alone:

Here, however, the analogy ceases. The iron, in the expression of the weight of the sugar-loaf, represents a natural property common to both bodies, namely their weight; but the coat, in the expression of value of the linen, represents a non-natural property of both, something purely social, namely, their value.

it is rather imbued upon the x and y in 'x is worth y' through the social relation of their labours; that is insofar as both x and y are embodiments of human labour in the abstract.

Since the relative form of value of a commodity – the linen, for example – expresses the value of that commodity, as being something wholly different from its substance and properties, as being, for instance, coat-like, we see that this expression itself indicates that some social relation lies at the bottom of it. With the equivalent form it is just the contrary. The very essence of this form is that the material commodity itself – the coat – just as it is, expresses value, and is endowed with the form of value by Nature itself. Of course this holds good only so long as the value relation exists, in which the coat stands in the position of equivalent to the linen.[22]

Above, Marx summarises before moving on to a more metaphysical interpretation of the same idea:

Since, however, the properties of a thing are not the result of its relations to other things, but only manifest themselves in such relations, the coat seems to be endowed with its equivalent form, its property of being directly exchangeable, just as much by Nature as it is endowed with the property of being heavy, or the capacity to keep us warm.Hence the enigmatical character of the equivalent form which escapes the notice of the bourgeois political economist, until this form, completely developed, confronts him in the shape of money. He then seeks to explain away the mystical character of gold and silver, by substituting for them less dazzling commodities, and by reciting, with ever renewed satisfaction, the catalogue of all possible commodities which at one time or another have played the part of equivalent. He has not the least suspicion that the most simple expression of value, such as 20 yds of linen = 1 coat, already propounds the riddle of the equivalent form for our solution.

We do not see the social relation which imbues commodities with their values in the exchange relation of relative and equivalent, so it appears as if only the physical properties of both commodities can serve to facilitate the comparison of their value. Nevertheless, Marx suggests that the exchangeability of two commodities and their exchange ratio is based upon a property of the coat (that it is a product of labour) and that property's relationship to other commodities (the relative magnitudes of their socially necessary labour times). Value persists in the relation of commodities and labours but nevertheless expresses itself as a definite property of the object; which is to say that Marx sees the value form as a social fact which imbues products of labour with value once entered into the exchange relation - once subsumed to the value form.

In a similar way to how use values are the form of manifestation of exchange values in the value form, concrete labour is the form of manifestation of abstract labour; Marx exploits the structural symmetry that was exhibited earlier:

In tailoring, as well as in weaving, human labour power is expended. Both, therefore, possess the general property of being human labour, and may, therefore, in certain cases, such as in the production of value, have to be considered under this aspect alone. There is nothing mysterious in this. But in the expression of value there is a complete turn of the tables. For instance, how is the fact to be expressed that weaving creates the value of the linen, not by virtue of being weaving, as such, but by reason of its general property of being human labour? Simply by opposing to weaving that other particular form of concrete labour (in this instance tailoring), which produces the equivalent of the product of weaving. Just as the coat in its bodily form became a direct expression of value, so now does tailoring, a concrete form of labour, appear as the direct and palpable embodiment of human labour generally. -

fdrake

7.2kSo far we have that if 'x coats is worth y yards of linen', the exchange value of the x coats expresses itself as a definite quantity ( y ) of the use value linen. Underpinning this is that the concrete labour which produces x coats meets the concrete labour which produces y yards of linen as abstract labour to abstract labour; they are only comparable once all qualitative particularities are filtered out which are not shared between both.

fdrake

7.2kSo far we have that if 'x coats is worth y yards of linen', the exchange value of the x coats expresses itself as a definite quantity ( y ) of the use value linen. Underpinning this is that the concrete labour which produces x coats meets the concrete labour which produces y yards of linen as abstract labour to abstract labour; they are only comparable once all qualitative particularities are filtered out which are not shared between both.

This means the commodity functioning as the equivalent expresses the value (exchange value) of the commodity in the relative position by being a definite quantity of a use value whose constitutive labour counts alone as abstract labour.

So we have that from the view of the exchange relation concrete labour inverts to abstract labour and expresses it in productive activity; contemporaneously use value inverts to exchange value (for commensurability) and back again (as a magnitudinal property, duration). Along with this the private labour which makes each commodity expresses itself solely as the character of social labour which is required for the production of any commodity. Marx continues:

Hence, the second peculiarity of the equivalent form is, that concrete labour becomes the form under which its opposite, abstract human labour, manifests itself.

But because this concrete labour, tailoring in our case, ranks as, and is directly identified with, undifferentiated human labour, it also ranks as identical with any other sort of labour, and therefore with that embodied in the linen. Consequently, although, like all other commodity-producing labour, it is the labour of private individuals, yet, at the same time, it ranks as labour directly social in its character. This is the reason why it results in a product directly exchangeable with other commodities. We have then a third peculiarity of the equivalent form, namely, that the labour of private individuals takes the form of its opposite, labour directly social in its form.

We have a little composite of linked abstractions which transform each-other in exchange:

The use value in the equivalent form expresses the exchange value of the relative form through their exchange ratio; the commensurability of the use value in the relative position and of the use value in the equivalent position is ensured by the two meeting as abstract labour alone; which forces the concrete labours of their production to act as the expression of their abstract labour; which ensures that the private labour of individuals insofar as it produces commodities is always already social labour. -

fdrake

7.2kThe remainder of the section is mostly reiteration through an example, going through Aristotle's analysis of value:

fdrake

7.2kThe remainder of the section is mostly reiteration through an example, going through Aristotle's analysis of value:

The two latter peculiarities of the equivalent form will become more intelligible if we go back to the great thinker who was the first to analyse so many forms, whether of thought, society, or Nature, and amongst them also the form of value. I mean Aristotle.

In the first place, he clearly enunciates that the money form of commodities is only the further development of the simple form of value – i.e., of the expression of the value of one commodity in some other commodity taken at random; for he says:

5 beds = 1 house (clinai pente anti oiciaς)

is not to be distinguished from

5 beds = so much money. (clinai pente anti ... oson ai pente clinai)

He further sees that the value relation which gives rise to this expression makes it necessary that the house should qualitatively be made the equal of the bed, and that, without such an equalisation, these two clearly different things could not be compared with each other as commensurable quantities. “Exchange,” he says, “cannot take place without equality, and equality not without commensurability". (out isothς mh oushς snmmetriaς). Here, however, he comes to a stop, and gives up the further analysis of the form of value. “It is, however, in reality, impossible (th men oun alhqeia adunaton), that such unlike things can be commensurable” – i.e., qualitatively equal. Such an equalisation can only be something foreign to their real nature, consequently only “a makeshift for practical purposes.”

Aristotle therefore, himself, tells us what barred the way to his further analysis; it was the absence of any concept of value. What is that equal something, that common substance, which admits of the value of the beds being expressed by a house? Such a thing, in truth, cannot exist, says Aristotle. And why not? Compared with the beds, the house does represent something equal to them, in so far as it represents what is really equal, both in the beds and the house. And that is – human labour.

The last paragraph, however, introduces some new material; the value form is a historical/contingent mechanism that comes along with societies organised consistently with it and those which either do not prohibit or promote its development; it is not a transhistorical feature of exchange.

There was, however, an important fact which prevented Aristotle from seeing that, to attribute value to commodities, is merely a mode of expressing all labour as equal human labour, and consequently as labour of equal quality. Greek society was founded upon slavery, and had, therefore, for its natural basis, the inequality of men and of their labour powers. The secret of the expression of value, namely, that all kinds of labour are equal and equivalent, because, and so far as they are human labour in general, cannot be deciphered, until the notion of human equality has already acquired the fixity of a popular prejudice. This, however, is possible only in a society in which the great mass of the produce of labour takes the form of commodities, in which, consequently, the dominant relation between man and man, is that of owners of commodities. The brilliancy of Aristotle’s genius is shown by this alone, that he discovered, in the expression of the value of commodities, a relation of equality. The peculiar conditions of the society in which he lived, alone prevented him from discovering what, “in truth,” was at the bottom of this equality.

That concludes the section on the equivalent form. Marx then synthesises his sections on the relative form and the equivalent form into a deeper exegesis of their composite; the elementary form of value. -

frank

19kJust a note: Aristotle was familiar with free markets which were in the process of revolutionizing his world. Like Plato, he was concerned with moral aspects of the market. Aristotle believed it was wrong to price commodities based on their value in the market. He thought they should be priced according the the wealth of the buyer.

frank

19kJust a note: Aristotle was familiar with free markets which were in the process of revolutionizing his world. Like Plato, he was concerned with moral aspects of the market. Aristotle believed it was wrong to price commodities based on their value in the market. He thought they should be priced according the the wealth of the buyer.

(my bold)In the first place, he clearly enunciates that the money form of commodities is only the further development of the simple form of value – i.e., of the expression of the value of one commodity in some other commodity taken at random;

If Aristotle thought that, he was wrong. Aristotle didn't have access to anthropological information about pre-money economies, and he would need that to see what money really replaces. It's not only an abstraction of the value of a commodity. Money is a symbol of the foundation of trust that allows any kind of exchange to take place. That foundation came in the form of palace officials prior to the invention of money. Those officials set exchange rates (of barley for copper, for instance.) Palaces did seek profit, but not from small-time exchanges that took place within their own realms as people sought to meet their needs. Profit came from international trade, which had cultural and psychological dimensions.

So if Marx wants to explain how a commodity comes to have any value at all, he's right that labor costs are a factor. If he wants to explain where money actually comes from, there are a few more pieces of the puzzle to dig up. Perhaps he'll get to that in the next chapter. -

fdrake

7.2kSo if Marx wants to explain how a commodity comes to have any value at all, he's right that labor costs are a factor. If he wants to explain where money actually comes from, there are a few more pieces of the puzzle to dig up. Perhaps he'll get to that in the next chapter. — frank

fdrake

7.2kSo if Marx wants to explain how a commodity comes to have any value at all, he's right that labor costs are a factor. If he wants to explain where money actually comes from, there are a few more pieces of the puzzle to dig up. Perhaps he'll get to that in the next chapter. — frank

I get the sneaking suspicion that you're not putting much effort into studying the book or my exegesis of it. In one of the opening posts I highlighted that Marx's analysis begins with the myth of barter rather than a robust history of trade; so it shouldn't be expected to have all the historical specifics of the development of capital right. Regardless, he has to give an account of all the moving parts in his ideas before knotting them together right.

This is what made the first exegesis I did, of the money commodity and money form explicitly, gloss over the details which I'm now working on.

So yeah, the historical development of money is interesting; but his analysis turns on does he have an accurate picture of how value, money and the like work in a capitalist system of production rather than did he deduce the value form from more appropriate anthropological records.

Yes, currency tokens redeemable in specific amounts of goods are the historical ur-form of money. Yes, this implicates debt and property relations as co-emergent with currency (which Marx acknowledges; see references to money of account and the property relations inherent in C-M-C' an M-C-M' in my opening posts). Yes, 'gift economies' with incredibly complicated social norms of repayment are as old as humans making stuff in communities. If this endangers Marx's account I'm all for exploring it; but you keep contrasting your points to your misconceptions (like 'labour costs' and your continual mixing up of value and price) rather than to Marx's account or my exegesis. -

fdrake

7.2k

fdrake

7.2k

If you do have substantive criticisms, can you please quote my exegesis or Marx? I also want discussions here to be mostly textual rather than freeform; so problems in Marx's logic, inaccurate examples or deductions, conceptual errors that make him necessarily elide relevant topics, bits he's missed - that kind of thing.

I acknowledge that the account so far would be better grounded in up to date anthropology. Though I do not see any obvious problems for Marx's account so far that arise from lack of knowledge of up to date anthropology. The only site of tension I see is between the modality of the links in the value form argument; abstract labour and value magnitudes being expressions of socially necessary labour time are both derived through a conceptual necessity; and the modality of the links as concrete historical circumstances; which are broad patterns of historical contingencies.

To some extent, the reasoning that occurs in Marx's analysis of the value form takes historical contingencies as grist for the conceptual mill; like the illustrative examples he uses which are clearly inspirations for him. This facilitates analysing the relationship of historical patterns by developing a web of concepts to link them. We don't look down at a good model's mathematical derivation for falling out of links of conceptual necessity because Nature hasn't derived it that way; we judge the derivation of the model on how well it captures the constitutive relations of its targeted phenomenon. (@Pierre-Normand due to similar themes from discussion 'Carlo Rivelli's...')

While it is nice to go through other bits of theory, like with @andrewk's kindly given examples about value and price, or @ssu's points earlier about the organisation of money being focussed on debt creation and management; I want to keep the thread on topic in the long term. So if these things touch on what's in the text so far, and their reference is needed to make a point, so be it. Otherwise, leave it. -

fdrake

7.2kSubsection 4: The Elementary Form of Value considered as a whole.

fdrake

7.2kSubsection 4: The Elementary Form of Value considered as a whole.

This section is mostly a summary of the Relative Form and Equivalent Form sections, and it sets up the analysis of the expanded form in the next section.

The first three paragraphs are recaps.

The elementary form of value of a commodity is contained in the equation, expressing its value relation to another commodity of a different kind, or in its exchange relation to the same. The value of commodity A, is qualitatively expressed, by the fact that commodity B is directly exchangeable with it. Its value is quantitatively expressed by the fact, that a definite quantity of B is exchangeable with a definite quantity of A. In other words, the value of a commodity obtains independent and definite expression, by taking the form of exchange value. When, at the beginning of this chapter, we said, in common parlance, that a commodity is both a use value and an exchange value, we were, accurately speaking, wrong. A commodity is a use value or object of utility, and a value. It manifests itself as this two-fold thing, that it is, as soon as its value assumes an independent form – viz., the form of exchange value. It never assumes this form when isolated, but only when placed in a value or exchange relation with another commodity of a different kind. When once we know this, such a mode of expression does no harm; it simply serves as an abbreviation.

Commodities are a composite of use and exchange value. The use value of the commodity is what it may be used for, the exchange value is what it may be exchanged for. Use and exchange are not on equal footing metaphysically, the use value follows from the physical properties imbued into the commodity during its acts of production; use value is product of concrete labour. Exchange value, however, follows from the social structure of exchange; specifically how much labour was expended in the production of the commodity. However, it is not the case that the value of a commodity is branded upon it by the specific duration of the concrete labour which produced it, rather the expenditure of human labour power in its production is socially mediated through the general social conditions for that commodity's production. In this manner, the exchange value arises from the statistical properties of the social processes of its production, not from the physical properties of the commodity. Furthermore, a commodity can only be said to have an exchange value when it is treated under the aspect of exchange; equated to others notionally or treated as equivalents in exchange.

Our analysis has shown, that the form or expression of the value of a commodity originates in the nature of value, and not that value and its magnitude originate in the mode of their expression as exchange value. This, however, is the delusion as well of the mercantilists and their recent revivers, Ferrier, Ganilh,[23] and others, as also of their antipodes, the modern bagmen of Free-trade, such as Bastiat. The mercantilists lay special stress on the qualitative aspect of the expression of value, and consequently on the equivalent form of commodities, which attains its full perfection in money. The modern hawkers of Free-trade, who must get rid of their article at any price, on the other hand, lay most stress on the quantitative aspect of the relative form of value. For them there consequently exists neither value, nor magnitude of value, anywhere except in its expression by means of the exchange relation of commodities, that is, in the daily list of prices current. Macleod, who has taken upon himself to dress up the confused ideas of Lombard Street in the most learned finery, is a successful cross between the superstitious mercantilists, and the enlightened Free-trade bagmen.

Marx stresses that the analysis of the form of value logically precedes concrete acts of exchange; he sees the form of value both as a condition of possibility for exchange and valuation to function as is in the sphere of capitalist production; and he sees it as a real component of what occurs to the commodity in terms of its value when it is subject to exchange. In this regard, we can view the analysis of the value form so far as (the beginnings of) a semantics of 'x is worth y' in capitalist production and exchange. The account of the meaning of 'x is worth y' consists in what it means for x to be in the first slot in the phrase; for it to be in the relative form; and for y to be in the second slot in the phrase; for y to be in the equivalent form. Marx summarises his developments on this topic:

A close scrutiny of the expression of the value of A in terms of B, contained in the equation expressing the value relation of A to B, has shown us that, within that relation, the bodily form of A figures only as a use value, the bodily form of B only as the form or aspect of value. The opposition or contrast existing internally in each commodity between use value and value, is, therefore, made evident externally by two commodities being placed in such relation to each other, that the commodity whose value it is sought to express, figures directly as a mere use value, while the commodity in which that value is to be expressed, figures directly as mere exchange value. Hence the elementary form of value of a commodity is the elementary form in which the contrast contained in that commodity, between use value and value, becomes apparent.

Every product of labour is, in all states of society, a use value; but it is only at a definite historical epoch in a society’s development that such a product becomes a commodity, viz., at the epoch when the labour spent on the production of a useful article becomes expressed as one of the objective qualities of that article, i.e., as its value. It therefore follows that the elementary value form is also the primitive form under which a product of labour appears historically as a commodity, and that the gradual transformation of such products into commodities, proceeds pari passu with the development of the value form.

'x is worth y' expresses the (exchange) value of x as a definite quantity of the use value of y. x counts as its exchange value while y counts as a definite quantity of use value. Therefore, a given amount of x is worth a given amount of y means the value of x is the given amount of y. Recognising that 'x is worth y' presents its constitutive social relations as a numerical equivalence, Marx notes that this also implies 'x is worth y'; the value form; is developed through history.

We perceive, at first sight, the deficiencies of the elementary form of value: it is a mere germ, which must undergo a series of metamorphoses before it can ripen into the price form.

The expression of the value of commodity A in terms of any other commodity B, merely distinguishes the value from the use value of A, and therefore places A merely in a relation of exchange with a single different commodity, B; but it is still far from expressing A’s qualitative equality, and quantitative proportionality, to all commodities. To the elementary relative value form of a commodity, there corresponds the single equivalent form of one other commodity. Thus, in the relative expression of value of the linen, the coat assumes the form of equivalent, or of being directly exchangeable, only in relation to a single commodity, the linen.

The elementary form of value is conceptually the simplest value form Marx analyses which is still relevant for capitalist production; the other forms of value make different uses of 'x is worth y' germinally, as its constitutive elements. When actually looking at commodities we can find that 'x is worth y' but also that 'x is worth z' and 'y is worth t', and all of these can be considered at once and co-occur as equivalent valuations. The elementary form of value provides a semantics solely for statements taking the form 'x is worth y' with no additional structure; no extra commodities or their exchange relations.

Nevertheless, the elementary form of value passes by an easy transition into a more complete form. It is true that by means of the elementary form, the value of a commodity A, becomes expressed in terms of one, and only one, other commodity. But that one may be a commodity of any kind, coat, iron, corn, or anything else. Therefore, according as A is placed in relation with one or the other, we get for one and the same commodity, different elementary expressions of value.[24] The number of such possible expressions is limited only by the number of the different kinds of commodities distinct from it. The isolated expression of A’s value, is therefore convertible into a series, prolonged to any length, of the different elementary expressions of that value.

Marx indicates that the next stage of his analysis of value will begin b making composites of 'x is worth y', of the form 'x is worth y', 'x is worth z' and so on. Having the relative value of x take on different commodities for its equivalent. Which leads us onto the next section, the expanded form of value. -

fdrake

7.2kSubsubsection: The Expanded Relative Form of Value

fdrake

7.2kSubsubsection: The Expanded Relative Form of Value

The major new feature of the expanded form of value over the elementary form of value is that value has become universal. This in the sense that a commodity stands as commensurable to all other commodities through exchange; with their exchange ratios determined with the same means as before.

The value of a single commodity, the linen, for example, is now expressed in terms of numberless other elements of the world of commodities.

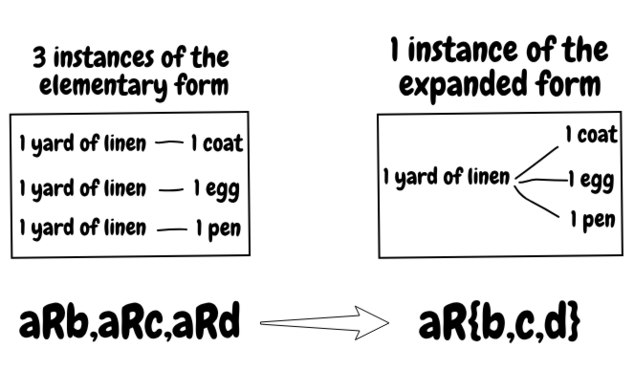

This is the meaning of mapping the elementary forms above; aRb, aRc, aRd to their composite in the expanded form: aR{b,c,d}. This means that 'a is worth b, a is worth c and a is worth d' transforms to 'a is worth b or c or d', and thus the relative value of a is now expressed in terms of all other commodities which share its worth.

In terms of the previous algebraic structure of commodities, the nature of the 'is worth' relation has changed from 'x is worth y' being a disordered (yet symmetric) set of pairs to 'x is worth [y]', where [y] is the collection of all commodities which are substitutable in this expression. Insofar as all commodities in a definite quantity have the same value as x they serve together as the equivalent form of value for x. Marx expands on this point using the previously established structural symmetries relating expressions of value to social characteristics of labour.

Every other commodity now becomes a mirror of the linen’s value.[25] It is thus, that for the first time, this value shows itself in its true light as a congelation of undifferentiated human labour. For the labour that creates it, now stands expressly revealed, as labour that ranks equally with every other sort of human labour, no matter what its form, whether tailoring, ploughing, mining, &c., and no matter, therefore, whether it is realised in coats, corn, iron, or gold.

For Marx, the expanded form of value obviously displays the homogeneity of human labour in terms of its value creative aspects which was hidden in the analysis of the elementary form alone. The qualitative particularity of commodities in terms of their useful physical characteristics (use values) and the acts of labour which imbue the commodity with those characteristics is completely suppressed in the expanded form; this is because the expanded form relates any quantity of a use value to some quantity of every other use value. Value becomes untethered from the elementary form to the extent that the elementary form completely iterates through the set of all commodities and maps pairs of commodities to their exchange ratios. As Marx puts it:

The linen, by virtue of the form of its value, now stands in a social relation, no longer with only one other kind of commodity, but with the whole world of commodities. As a commodity, it is a citizen of that world. At the same time, the interminable series of value equations implies, that as regards the value of a commodity, it is a matter of indifference under what particular form, or kind, of use value it appears.

The iteration of the elementary form of value through the set of commodities destroys the privilege of y in the 'x is worth y' relation; the form of manifestation of x's value is no longer a definite quantity of a fixed use value, it is of a set of all use values in quantities that render them equivalent to x. Marx expands on this point:

In the first form, 20 yds of linen = 1 coat, it might, for ought that otherwise appears, be pure accident, that these two commodities are exchangeable in definite quantities. In the second form, on the contrary, we perceive at once the background that determines, and is essentially different from, this accidental appearance. The value of the linen remains unaltered in magnitude, whether expressed in coats, coffee, or iron, or in numberless different commodities, the property of as many different owners. The accidental relation between two individual commodity-owners disappears.

The 'background' marks refers to is the commensurability of all commodities with each other; that they can all serve as the equivalent for any other in some determinate quantity. Marx points out a category error which this highlights; when we consider two goods with equivalent worth in capitalist regimes of production, what is special about 'x is worth y' as an expression of value for x? Nothing at all; this means that it would be impossible to determine the values for x and for y in terms of 'x is worth y' in the absence of this universal medium of exchange. Just as 'x is worth x' was a meaningless tautology before, 'x is worth y' loses its specific meaning as the expression of x's value because x's value distributes over the entire set of commodities. Concrete acts of exchange, incidents of the relation 'x is worth y', lose their capacity to determinately express x's value even though they still express x's value as a mere instance of the expanded form. Thus Marx points out:

It becomes plain, that it is not the exchange of commodities which regulates the magnitude of their value; but, on the contrary, that it is the magnitude of their value which controls their exchange proportions.

2. The particular Equivalent form

Marx exploits the structural symmetry between use/exchange values and concrete/abstract labour to chart the transformation of labour under the expanded form:

Each commodity, such as, coat, tea, corn, iron, &c., figures in the expression of value of the linen, as an equivalent, and, consequently, as a thing that is value. The bodily form of each of these commodities figures now as a particular equivalent form, one out of many. In the same way the manifold concrete useful kinds of labour, embodied in these different commodities, rank now as so many different forms of the realisation, or manifestation, of undifferentiated human labour.

The iteration of 'x is worth y' through the set of commodities also conditions the concrete instances of labour which produce x and y; y is now an arbitrary placeholder which represents the set of quantities of commodities which can serve as an equivalent to x. The universalisation of value over the commodities maps the functioning of the value form explicitly to all of its quantitative exchange relations; and insofar as it does this, human labour embodied in each commodity is equated to human labour embodied in any other; yielding the sum total of productive labour as an amorphous goop (of abstract labour) as far as the value form is concerned. -

fdrake

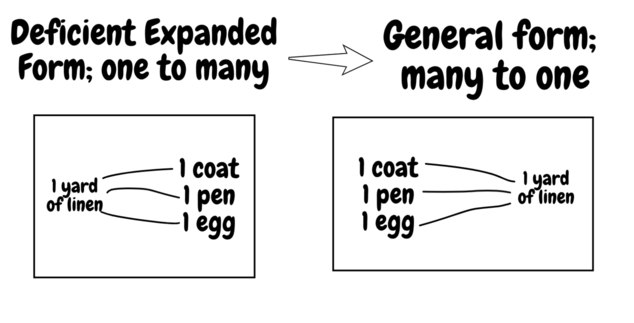

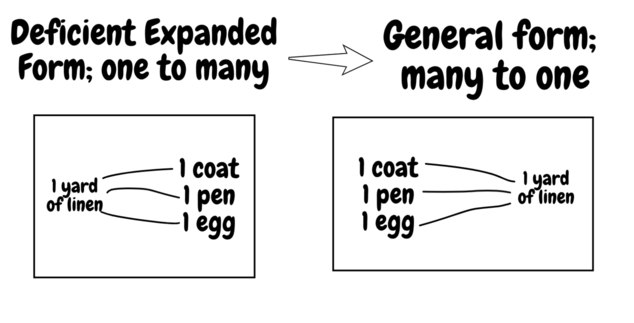

7.2kThe above diagram represents what I believe is the intuition behind Marx's diagnosis of 'defects' in the expanded form of value developed thus far. Marx begins his analysis of these defects as follows:

fdrake

7.2kThe above diagram represents what I believe is the intuition behind Marx's diagnosis of 'defects' in the expanded form of value developed thus far. Marx begins his analysis of these defects as follows:

In the first place, the relative expression of value is incomplete because the series representing it is interminable. The chain of which each equation of value is a link, is liable at any moment to be lengthened by each new kind of commodity that comes into existence and furnishes the material for a fresh expression of value.

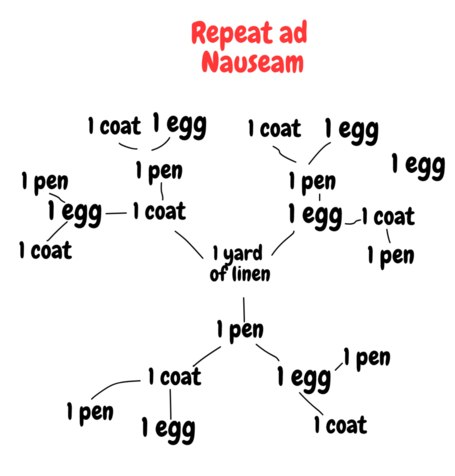

Imagine that we start from a commodity, pictured above as 1 yard of linen, and we have its set of equivalents: 1 egg, 1 pen, 1 coat. The only way we can express the value of 1 yard of linen is to put it in the relative form with respect to some equivalent; but we have 1 egg, 1 pen and 1 coat as the set of equivalents. We wish to obtain a determinate expression for the value of 1 yard of linen, and must thus appeal to an equivalent for it. However, as soon as we obtain an equivalent for it (either 1 egg, 1 pen or 1 coat), that commodity's relative value is expressed through its own 'is worth' relations; and is substitutable for all the commodities for which it has equivalent worth. We can keep substituting like this and end up with this expanding graph emanating from 1 yard of linen as its source.

To be sure, each 'x is worth y' does indeed express the value of x in terms of y, but the value of y must also be expressed in terms of one of its equivalents to make sense of the idea that the equivalent is now a set of commodities rather than any specific one. Universal commensurability was obtained in the value form at the price of the indeterminacy of each instance of the 'is worth' relation; whose destruction manifests as a one to many relationship between the relative and equivalent forms. This renders indeterminate the expression of relative values with precisely the same mechanism as it renders commensurable a commodity with every other. Marx continues:

In the second place, it is a many-coloured mosaic of disparate and independent expressions of value. And lastly, if, as must be the case, the relative value of each commodity in turn, becomes expressed in this expanded form, we get for each of them a relative value form, different in every case, and consisting of an interminable series of expressions of value.

and highlights a second deficiency of the expanded form analysed so far. The diagram above shows what happens when you try to obtain the value of a commodity through an equivalent solely with reference to the expanded form; a ceaseless chain of substitutable elements. Such a chain is not guaranteed to be the same for every commodity; indeed if we took half a yard of linen the quantities of commodities it is exchanged for differ and produce different nodes on the graph. This means that the relative form is not consistent over commodities despite portraying the same essential relationship of value equivalence.

The defects of the expanded relative value form are reflected in the corresponding equivalent form. Since the bodily form of each single commodity is one particular equivalent form amongst numberless others, we have, on the whole, nothing but fragmentary equivalent forms, each excluding the others. In the same way, also, the special, concrete, useful kind of labour embodied in each particular equivalent, is presented only as a particular kind of labour, and therefore not as an exhaustive representative of human labour generally. The latter, indeed, gains adequate manifestation in the totality of its manifold, particular, concrete forms. But, in that case, its expression in an infinite series is ever incomplete and deficient in unity.

'Each excluding the others' references that once a definite quantity of a commodity is selected, the above diagram would have all of its nodes relabelled; the set of all commodities becomes relativised to a particular commodity, despite that 'x is worth y' should be a statement of equivalent worth in the same sense. The 'sense' of 'x is worth y' in the deficient expanded form is given by these ceaselessly expanding graphs, unique in node labels for every originating commodity. -

fdrake

7.2kMarx proceeds to 'fix' these problems (lack of unity, indeterminate expression) in the expanded form.

fdrake

7.2kMarx proceeds to 'fix' these problems (lack of unity, indeterminate expression) in the expanded form.

First exploiting the symmetry condition of the 'is worth' relation:

The expanded relative value form is, however, nothing but the sum of the elementary relative expressions or equations of the first kind, such as:

20 yards of linen = 1 coat

20 yards of linen = 10 lbs of tea, etc.

Each of these implies the corresponding inverted equation,

1 coat = 20 yards of linen

10 lbs of tea = 20 yards of linen, etc.

In fact, when a person exchanges his linen for many other commodities, and thus expresses its value in a series of other commodities, it necessarily follows, that the various owners of the latter exchange them for the linen, and consequently express the value of their various commodities in one and the same third commodity, the linen. If then, we reverse the series, 20 yards of linen = 1 coat or = 10 lbs of tea, etc., that is to say, if we give expression to the converse relation already implied in the series, we get.

(my drawing rather than Marx's)

This gives valuation the structure of a surjective function on the set of commodities; a set of commodities of equivalent value is mapped to a specific amount of one commodity which serves as the equivalent. -

fdrake

7.2kSo one puzzle here is that the general form of value (depicted on the right above) is consistent with the deficient expanded form of value (on the left above); the first and the second are dual notions. This is scouting ahead a bit, but it's worthwhile showing exactly why transitivity is an important component of the value form.

fdrake

7.2kSo one puzzle here is that the general form of value (depicted on the right above) is consistent with the deficient expanded form of value (on the left above); the first and the second are dual notions. This is scouting ahead a bit, but it's worthwhile showing exactly why transitivity is an important component of the value form.

What this means precisely is that if we have aRb, aRc, aRd, where a is the yard of linen, b the coat, c the pen and e the egg, then we also have bRa , cRa and dRa in the value form when conceived as the relation T on the set of commodities - again, this is because the relation is symmetric. If the two notions are dual; like 'less than or equal to' and 'greater than or equal to'; how can one be deficient and the other not when one is just the transposition of the other?

Marx summarises the deficiency as follows:

The (Any specific equivalent), indeed, gains adequate manifestation in the totality of its manifold, particular, concrete forms. But, in that case, its expression in an infinite series is ever incomplete and deficient in unity.

And summarises why transposing the deficient to the general form solves the problem:

All commodities now express their value (1) in an elementary form, because in a single commodity; (2) with unity, because in one and the same commodity. This form of value is elementary and the same for all, therefore general.

Mathematically then, removing the deficiencies of the expanded form has to place a single commodity as an equivalent for the infinite series of commodities; that commodity's relative value is then expressed through the commodities in that chain. Moreover, the commodities in that chain should present a single magnitude of value. As Marx puts it:

All commodities being equated to linen now appear not only as qualitatively equal as values generally, but also as values whose magnitudes are capable of comparison. By expressing the magnitudes of their values in one and the same material, the linen, those magnitudes are also compared with each other. For instance, 10 lbs of tea = 20 yards of linen, and 40 lbs of coffee = 20 yards of linen. Therefore, 10 lbs of tea = 40 lbs of coffee. In other words, there is contained in 1 lb of coffee only one-fourth as much substance of value – labour – as is contained in 1 lb of tea

Here is the first explicit mention of the transitivity of T. 10 tea = 20 linen, 20 linen = 40 coffee, 10 tea = 40 coffee. So the 'deficiency in unity' of the relative form is solved by requiring the transitivity of T; which means that T is now reflexive, symmetric and transitive. An equivalence relation - like equality of numbers. This partitions the set of commodities into subsets of equal worth.

However, the raw equivalence relation itself is still applicable to the expanded form of value with its deficiencies intact. If we wanted to look at the expanded form in general and obtain the value of say 1 yard of linen, how could we do this? We need to avoid this many-to-one relationship when trying to value 1 yard of linen, otherwise its expression is 'deficient in unity'.

Which is to say, if we want to obtain the value of 1 yard of linen, we should take only the elements of T which have 1 yard of linen in the right position; collecting all x for which 'x is worth 1 yard of linen'. If we do this in my example with pens, eggs and coats, this gives the set {1 pen, 1 egg, 1 coat, (1 yard of linen, but ignore this}} mapping to {1 yard of linen}. Can we conclude from this set up that 1 pen, 1 egg and 1 coat are of equivalent value?

We have that 1 pen is worth 1 yard of linen, but also that 1 yard of linen is worth 1 egg. Therefore 1 pen is worth 1 egg. What this entails is 'chasing arrows' along the diagram, if there is a path between a commodity and another commodity then they are worth the same. This means that all {1 pen, 1 egg, 1 coat} are all connected through 1 yard of linen, and so are worth the same. We also have that for all commodities xTy and yTz imply xTz (argument for this is simple; link all commodities through their equivalent, the whole thing is a 'chain of equations' 1 pen <-> 1 egg <-> 1 coat <-> 1 pen, and this is what a transitive relation looks like). So when T is restricted in the manner: {x in C such that xT(1 yard of linen) }, it becomes a surjective function from C to {1 yard of linen} (avoiding many to one) and everything in that set is of equivalent worth. -

fdrake

7.2kGoing through the section more meticulously now, this expands on the exegesis for the Marx's solution to the deficiency in the expanded form and that forms' modification to the general form A,B,C denote the forms of value pictured above. A is elementary, B is expanded with deficiency, C is expanded with the deficiency removed; general.

fdrake

7.2kGoing through the section more meticulously now, this expands on the exegesis for the Marx's solution to the deficiency in the expanded form and that forms' modification to the general form A,B,C denote the forms of value pictured above. A is elementary, B is expanded with deficiency, C is expanded with the deficiency removed; general.

Considering C as compared to A and B:

All commodities now express their value (1) in an elementary form, because in a single commodity; (2) with unity, because in one and the same commodity. This form of value is elementary and the same for all, therefore general.

The recipe to move from the deficient expanded form to the general form is to place a restriction on the 'is worth' relation T. A restriction of a relation confines that relation to when defined properties hold of its inputs. EG, if we have the relation 'x is taller than y' on the set of all humans, we can restrict that relation to children and obtain an ordering on children's heights rather than children and adults. Formally what this looks like is:

where T is the 'is worth' relation and P(x,y) is some property of either x or y or both. In the case pictured above, the relation T looks like this for the deficient form (with the notionally equal values and reflexives thrown in):

had to change to () and split it up because {} breaks with longer equations for some reason. The restriction of the deficient form to only those pairs which have a in the place on the right yields:

which defines a function on {a,b,c,d} to {a} such that every element besides a is mapped onto a. This function supplies the conditions (1) and (2) - only one entity occupies the position of equivalent ( a )

and it is the only member of its set (unity). Also the plurality of elements in the relative form is annihilated in terms of their value because T holds between them all. Another way to think of this is that what we are doing is picking a single element, a, out of the equivalence relation, T, finding a's equivalence class [a] (all elements related to a), then mapping all the elements in [a] besides a to a.

Excluding (a,a) from T is almost the same as choosing a representative of the equivalence class as discussed before, if we also map a to a then this really is choosing a representative. a 'avoids' this map because for Marx aTa never holds, but since including it is harmless (as argued before), we can map a to a and obtain a substantial theoretical insight and simplification. The value of a commodity is equal to the value of any of its equivalents.

Because equivalence relations partition the set of commodities, this renders the value unique for any commodity and a single commodity (even the same one for each class, which will appear in varying amounts for each class) can be chosen as the representative for each equivalence class. So 'a' could be chosen for all of them.

So the restriction onto 'targeting a' is better thought of as choosing a representative for the equivalence class. Note that completing the relation by applying symmetry, transitivity and reflexivity to T|a yields T again - the deficient form never 'went away' and the equivalence classes use it to express value determinately - as desired.

For the sake of explicitness, choosing a as the representative of the equivalence class (a,b,c,d) is this mapping F=(a->a,b->a,c->a,d->a). Restricting T to a (forming T|a) without including the pair (a,a) in T (excluding reflexives) gives G=(b->a,c->a,d->a). It's obvious that if we include a in the set G works on we end up with F; choosing a as the representative.

The forms A and B were fit only to express the value of a commodity as something distinct from its use value or material form.

The first form, A, furnishes such equations as the following: – 1 coat = 20 yards of linen, 10 lbs of tea = ½ a ton of iron. The value of the coat is equated to linen, that of the tea to iron. But to be equated to linen, and again to iron, is to be as different as are linen and iron. This form, it is plain, occurs practically only in the first beginning, when the products of labour are converted into commodities by accidental and occasional exchanges.

From the perspective of the elementary form A, we can imagine an isolated series of trade relations each saying x is worth y and y is worth x. Following the myth of barter, this tracks 'accidental' exchanges before the transformation of an economy into commodity production. The elementary form of value, as frank pointed out earlier (and I pointed out in an opening post) doesn't actually reflect the form of value in a capitalist economy (too little structure for its general function). If trades remain isolated and goods are not produced primarily for exchange , considerations of relative utility rather than relative value will be the norm.

The second form, B, distinguishes, in a more adequate manner than the first, the value of a commodity from its use value, for the value of the coat is there placed in contrast under all possible shapes with the bodily form of the coat; it is equated to linen, to iron, to tea, in short, to everything else, only not to itself, the coat. On the other hand, any general expression of value common to all is directly excluded; for, in the equation of value of each commodity, all other commodities now appear only under the form of equivalents. The expanded form of value comes into actual existence for the first time so soon as a particular product of labour, such as cattle, is no longer exceptionally, but habitually, exchanged for various other commodities.

Form B is adopted when a trade network expands and begins to centralise around a set of privileged goods. Value obtains no unitary and substrate-independent expression in this form (recall the notes on the indeterminacy of the expanded form), rather goods obtain their values through what they may be traded for normally. It consists of coupled and inter-related elementary forms with several centralising commodities; like cattle, shells, patches of cloth for real world examples. Comparisons of utility may still drive exchanges somewhat, but this form of value is the first time that a mercantile, 'get more stuff' perspective can be adopted towards the entire network of goods. Amassing wealth in this form is still associated with amassing use values rather than exchange value (due to the indeterminacy of the expression of value).

The third and lastly developed form expresses the values of the whole world of commodities in terms of a single commodity set apart for the purpose, namely, the linen, and thus represents to us their values by means of their equality with linen. The value of every commodity is now, by being equated to linen, not only differentiated from its own use value, but from all other use values generally, and is, by that very fact, expressed as that which is common to all commodities. By this form, commodities are, for the first time, effectively brought into relation with one another as values, or made to appear as exchange values.

Form C, the general form, requires that the entire trade network is able to be relativised to the production of one good (restricting T to a in my example, restricting to linen in Marx's), but the logic works for any good to obtain its value in a definite amount. The social norms surrounding trade centralise around the trade of a particular good for goods in general and goods in general in a definite amount have their measure in an amount of that particular good. This produces a substrate independent character to value; it no longer needs to relate to anything but the mere presence of utility (bearing a use value, being the product of social labour); and the properties of the value of commodities become aligned with the statistical properties of their production processes; of human labour in the abstract.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- 'Quantum Jumping', 'Multiverse' Theory, and explaining experiential phenomena in "lower-level terms"

- A Correct Formulation of Sense-Datum Theory in First-Order Logic

- Possible revival of logical positivism via simulated universe theory.

- Myth-Busting Marx - Fromm on Marx and Critique of the Gotha Programme

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum