-

TheMadFool

13.8kI was reading a wikipedia article on ontology and it seems its history stretches back nearly 2000 years to the presocratic Greek philosophers. What I then remember is seeing an image of an archaeologist stooping over some shapeless rock, carefully chipping away at it until something almost magical happens; the easily identifiable shape of a bone emerges from the rock. As the archaeologist keeps at it, more bones are carefully exposed and these bones articulate with each other at just the right places to reveal the form of an ancient animal.

Like these fossils, do philosophical concepts have origins deep in the human mind's past? Were they then discovered by interested parties of philosophers, worked on over a lifetime and beyond, revealing the core underlying ideas, like fossil bones in rocks? While many philosophical concepts are actually valuable it's possible that many of them are nothing more than poorly conceived notions that philosophers would deem unworthy of their time, like rocks that don't yield fossils.

A further question is, do the central ideas of philosophy like ethics, metaphysics, ontology, epistemology, etc. unite, like the fossil bones, into a coherent whole, like the ancient animal the bones belong to?

Comments... -

javra

3.2kComments... — TheMadFool

javra

3.2kComments... — TheMadFool

As for myself, furthering this metaphor, many species of thought have become extinct. We might be able to discover their fossilized remains within our history - but the allegorical flesh and nervous system of these can only be imperfectly inferred. The fragments of Heraclitus’ philosophy to me seem a good example of this. As with physical manifestations of life, those species of thought that have gone extinct are forever to remain extinct. Nevertheless, via analogous evolution, we find many of the same forms of belief in today’s species of thought that once pertained to now extinct species of thought. Process theory is a different, currently living, species of thought than that of Heraclitus’s now extinct philosophy of global flux - unlike process theory, the latter being fully grounded in an understanding of logos as natural law (of which our own human reasoning, replete with its laws of thought, was only a sub-constituent of), this being a species of thought that now no longer is. Yet the analogously evolved properties between today’s process theories and Heraclitean philosophy is blatantly present all the same. And, alongside analogous evolutionary processes, there are also homologous evolutionary processes: the gradual change from one species of thought into another. As one example, what was once the Empiricist driven period of the so-called Enlightenment in the west steadily morphing into today’s physicalism (as one crucial difference, ideas were empirical to the likes of Lock and Hume, whereas against the backdrop of today’s species of thought termed physicalism, that which is empirical is today strictly constituted of what can be grasped via sensory receptors - which, in today’s species of thought, precludes ideas from so being empirically known).

I have little interest in justifying these affirmations, so one can chalk them all up to being mere opinions. But, given this general outlook:

Just as the changes that occur in physical manifestations of life - which are commonly termed “(biological) evolution” - hold global limitations and attributes (e.g., the adaptation of life to that which is objectively real via, in part, life’s random mutations – here simplistically expressing something very complex), so too can be expressed for the evolution of species of philosophical thought: these too are bound to global limitations and attributes. As an additional offered opinion and nothing more, all species of philosophical thought evolve - via both analogous and homologous processes - via adaptation to that which is objectively (here understood as "impartially" rather than "physically") real; this, in part, through at times random changes that can for example obtain though trial and error, novel intuitions, and the like.

A species of philosophical thought that would, for example, affirm that one can fly off of tall buildings by flapping one’s hands were one to will it with sufficient force will not last long.

On the other hand, studying the so-called fossils of bygone species of philosophical thought can at times help us better understand the global aspects of – here, primarily metaphysical – reality; in particular, those global aspects which makes the analogously evolved properties of certain species of thought reoccur throughout history.

------------

Yup, nothing here but the poetic articulation of a metaphorical perspective regarding philosophy’s history - with not an ounce of proper justification to any of it. But, then, in my own defense, the OP was drenched in metaphor to begin with. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kA further question is, do the central ideas of philosophy like ethics, metaphysics, ontology, epistemology, etc. unite, like the fossil bones, into a coherent whole, like the ancient animal the bones belong to? — TheMadFool

Pfhorrest

4.6kA further question is, do the central ideas of philosophy like ethics, metaphysics, ontology, epistemology, etc. unite, like the fossil bones, into a coherent whole, like the ancient animal the bones belong to? — TheMadFool

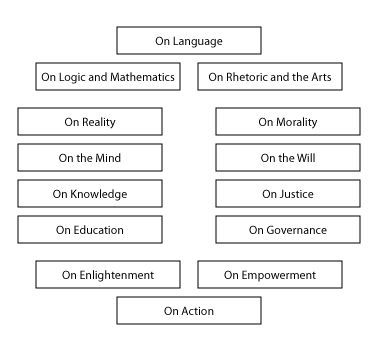

I think definitely yes. All actions is driven by comparing what is with what ought to be. All of philosophy can be structured as questions about what is, and what ought to be, what is real, and what is moral; and then about what it means to be real or to be moral (philosophy of language, metaethics), what criteria we use to assess whether something deserves such a label (ontology, parts of normative ethics), what methods we use to apply those criteria (epistemology, more normative ethics), what faculties we need to enact those methods (philosophy of mind and will), who is to exercise those faculties (philosophies of education and governance), and why any of it matters.

Questions about what our questions even mean, investigating questions about language; what criteria we use to judge the merits of a proposed answer, investigating questions about being and purpose, the objects of reality and morality respectively; what methods we use to apply those criteria, investigating questions about knowledge and justice; what faculties we need to enact those methods, investigating questions about the mind and the will; who is to exercise those faculties, investigating questions about academics and politics; and why any of it matters at all.

-

Pfhorrest

4.6kobjectively (here understood as "impartially" rather than "physically") — javra

Pfhorrest

4.6kobjectively (here understood as "impartially" rather than "physically") — javra

To my ear “objective” always means “impartial”, and what makes physical stuff objectively real is precisely that it can be impartially determined to exist, vis our common (and therefore unbiased) experiences.

People who take “objective” to mean “physical” just introduce unnecessary confusion and baggage to discussions about the objectivity of things other than reality (like morality, for example). -

javra

3.2kTo my ear “objective” always means “impartial”, and what makes physical stuff objectively real is precisely that it can be impartially determined to exist, vis our common (and therefore unbiased) experiences.

javra

3.2kTo my ear “objective” always means “impartial”, and what makes physical stuff objectively real is precisely that it can be impartially determined to exist, vis our common (and therefore unbiased) experiences.

People who take “objective” to mean “physical” just introduce unnecessary confusion and baggage to discussions about the objectivity of things other than reality (like morality, for example). — Pfhorrest

Fully agreed. To add: Culturally, this can often get confusing due to the commonly understood semantics of "objects" - despite, for example, concepts being objects of awareness. We're often habituated into thinking that objects are always necessarily physical and, as a result, end up thinking of objectivity as being the physicality which applies to (physical) objects. Whereas, as you say, each physical object holds an impartial existence to all coexistent sentient beings - and is (or at least can coherently be conceptualized as being) thereby objective precisely due to its nature of being impartially applicable all subjects. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

Sounds like you're thinking of something like Jung's Racial Memory or Collective Unconscious, and Plato's Archetypes. These are interesting possibilities, but are scientifically debatable.Like these fossils, do philosophical concepts have origins deep in the human mind's past? — TheMadFool

Racial Memory : https://dictionary.apa.org/racial-memory

https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/genetic-memory-how-we-know-things-we-never-learned/

Archetypes : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archetype -

javra

3.2kPeople who take “objective” to mean “physical” just introduce unnecessary confusion and baggage to discussions about the objectivity of things other than reality (like morality, for example). — Pfhorrest

javra

3.2kPeople who take “objective” to mean “physical” just introduce unnecessary confusion and baggage to discussions about the objectivity of things other than reality (like morality, for example). — Pfhorrest

Since I’ve recently had the issue of governance on my mind, wanted to embellish my previous reply to this with something that is of interest to me - though, no doubt, which will be a highly dubious use of semantics to others.

As with the multiple meaning of “objective” - e.g., from that which is impartial to that which as noun is a goal – “to be a subject” too has its multiple meanings.

With that in mind, as an at the very least metaphoric appraisal of nature at large: Given the interpretation of objectivity which we so far agree upon, all subjective beings can thereby be further concluded via this mode of thought to inescapably be subjects to objectivity as ultimate authority - a power which the power of all subjects is conditional upon. Waiver too much from that which is objective, i.e. fully impartial, and the individual perishes. Stay accordant to objectivity and the individual holds the potential to flourish.

Of note, though, objectivity is in no way a psyche - nor can it be. We as psyches can be more objective by comparison to others or to other personally held states of mind - but our very nature of being individual selves precludes us from actualizing a perfectly impartial state of being. Hence, in this interpretation, we are above all subjects to a collectively shared, impartial reality - rather than being subjects to some monarch, some other leader, or some superlative incorporeal deity. No physical or spiritual sentient being to bow down to here.

You touched upon notions of an objective right and wrong - at least as possibilities to consider. To me, this too would then be a perfectly impartial, here metaphysical, reality. What some have termed, “the Real,” and what Plato termed “the Good” - this then, imv, being a metaphysical objectivity which holds at least some overtones to the neo-Platonic notion of “the One,” from which physicality was stated to emerge. But again - even when a neo-Platonic frame of mind is considered - I fail to fathom how “the Good” could in any way be a psyche and, hence, a deity. For, again, as that which is fully objective, it would need to be perfectly impartial in all conceivable ways. And a psyche always remains to some extent partial toward that which is good for itself, if nothing else.

With all this briefly mentioned for the sake of some background, that we as sentient beings are all subjects to, first and foremost, objectivity as ultimate authority is to me something that has a rather aesthetic appeal.

At any rate, since I started off with poetic mumbo-jumbo in this thread, I figured complimenting it with this take on the subjectivity/objectivity dichotomy can’t by now hurt too much. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kYou touched upon notions of an objective right and wrong - at least as possibilities to consider. To me, this too would then be a perfectly impartial, here metaphysical, reality. — javra

Pfhorrest

4.6kYou touched upon notions of an objective right and wrong - at least as possibilities to consider. To me, this too would then be a perfectly impartial, here metaphysical, reality. — javra

I think I agree with the gist of your overall post, but I'd quibble with this little bit. Morality doesn't have to be "a reality" of any sort; what is real and what is moral can be completely unrelated questions. For something to be objectively moral doesn't require that reality (objective or otherwise) be any particular way; there don't have to be "queer" moral facts of some strange metaphysical nature.

All it takes for there to be an objective morality are for there to be things that are good from an impartial, unbiased perspective. To figure out what is objectively moral, take whatever methods you use to figure out what is subjectively moral, and compensate for the bias. Just like we judge objective reality with our (necessarily subjective) empirical experiences (what "looks true"), cancelling out the bias of our subjectivity by abstracting our interpretations of those experiences from the experiences themselves, accounting equally for everyone's experiences, and then devising new interpretations of those mutual, common experiences, so too we can judge objective morality by starting with our (necessarily subjective) hedonic experiences what ("feels good"), and then cancelling out the bias of that subjectivity in exactly the same way, abstracting our interpretations of those experiences from the experiences themselves, accounting equally for everyone's experiences, and then devising new interpretations of those mutual, common experiences. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kAlso...

Pfhorrest

4.6kAlso...

Given the interpretation of objectivity which we so far agree upon, all subjective beings can thereby be further concluded via this mode of thought to inescapably be subjects to objectivity as ultimate authority — javra

In my book I actually subtitle the essays on Mind and Will as being about "...the Subjects of Reality" and "...the Subjects of Morality", inasmuch as the mind is the facet of a person that experiences reality, is subject to it, has to decipher what it is, what is real, what is true; and likewise the will is the facet of a person that experiences morality, or is subject to it, in that the will has to decipher what morality, is, what is moral, what is good, i.e. what ought to be, what a person ought to do, i.e. to make a choice. (I take the connection between free will and moral responsibility very seriously, going so far as equating free will with the efficacy of moral reason: your will is what you think is the best thing to do, and your will is free when thinking something is the best thing for you to do causes you to do it). -

Wayfarer

26.1kAll it takes for there to be an objective morality are for there to be things that are good from an impartial, unbiased perspective. T — Pfhorrest

Wayfarer

26.1kAll it takes for there to be an objective morality are for there to be things that are good from an impartial, unbiased perspective. T — Pfhorrest

You still don’t understand the sense in which you’re a moral relativist. But it is abundantly clear from this:

Morality doesn't have to be "a reality" of any sort; what is real and what is moral can be completely unrelated questions — Pfhorrest

So let me spell it out, in a stream-of-consciousness sort of way: moral realism insists that there is a true good, a real good, which is *not* dependent on your or my or anyone’s viewpoint, opinion or even consent; it simply *is thus*. It would be good, sans the agreement of anyone whatever. But because our thinking is entirely oriented around egoic consciousness, then we can only understand what’s good in terms of what either we, or people like ourselves, understand to be good, in ‘hedonic’ terms, as you often say.

So, here’s a counter-factual to your view: In traditional philosophy - premodern, mainly - there’s an axiom, often unstated, that one of the attributes of sagacity is to ‘see things as they truly are’. The sage sees thus, because the sage is impartial - indifferent to his/her own interests, but fully cognisant of the interests of others. Kind of disinterestedly compassionate.

Now, modern science tries to emulate this attribute, but the fatal difficulty is that modern science defines itself only in terms of what is measurable, what can be quantified. But consider that this is because of the same factor which dictates that ‘only the measurable is real’ in modern science: which is the exclusion of the perspective of the subject, so as to arrive at the mathematically-idealised depiction of an issue in the quantifiable terms of Galilean science.

So among other things, there’s a higher criterion than ‘objectivity’ at play in ethical theory. What is ‘objective’ is itself dependent on subsidiary factors, such as which scale you use, what you choose to measure, and so on. All of this points towards the quandary that expresses itself as moral relativism: the contest of opinions as to what is truly good. The higher criterion is necessarily religious, insofar as it is represented by our willingness to assent to the possibility that the sage/moral exemplar knows something that we do not, and that furthermore cannot be determined by empirical means alone. That’s a big statement but I think one worth making, and one for which there is a lot of precedent and example, even in the desiccated post-industrial wasteland of modernity. ;-) -

Pfhorrest

4.6kyou’re a moral relativist — Wayfarer

Pfhorrest

4.6kyou’re a moral relativist — Wayfarer

Not at all.

moral realism — Wayfarer

Is not synonymous with moral objectivism.

The sage sees thus, because the sage is impartial - indifferent to his/her own interests, but fully cognisant of the interests of others. Kind of disinterestedly compassionate. — Wayfarer

That’s exactly what I’m advocating.

Hedonism is just about what constitutes an interest, not whose interests matter.

Hedonism is not synonymous with egotism. -

Wayfarer

26.1kwas reading a wikipedia article on ontology and it seems its history stretches back nearly 2000 years to the presocratic Greek philosophers. — TheMadFool

Wayfarer

26.1kwas reading a wikipedia article on ontology and it seems its history stretches back nearly 2000 years to the presocratic Greek philosophers. — TheMadFool

In actual fact, the word ‘ontology’ is of much more recent origin - around 16th C or so - from the first person conjugation of the Greek ‘ouisia’, to be, meaning that ‘ontology’ is strictly speaking the study of being from a first-person perspective; the study of ‘I Am’, you might say - a point that is often lost. -

javra

3.2kmoral realism insists that there is a true good, a real good, which is *not* dependent on your or my or anyone’s viewpoint, opinion or even consent; it simply *is thus*. — Wayfarer

javra

3.2kmoral realism insists that there is a true good, a real good, which is *not* dependent on your or my or anyone’s viewpoint, opinion or even consent; it simply *is thus*. — Wayfarer

Given my (maybe peculiar) interpretations, this could be else worded as that which “just-is” (in the sense of being sans cause) … also, with “just” in part meaning “right, correct, impartial, and fair” – a notion from which the notions of both justice and justification - as well as the aesthetic (fair as that which is both pleasing and moral) - are derived. For instance – here imperfectly expressed - when we justify a belief we seek to evidence that that which is believed is impartially, factually, so - and, in so doing, imv we seek to align our beliefs to that which “just is” (rather than to our egoic wants or needs of what is; i.e., it’s not because I or you so say it is but because it is an impartial given that thereby is aligned to perfect impartiality, to that which just is).

This general notion then stands in contrast to the idea that that which is just will be the effect of one or more psyches (as can for example be stated of mainstream monotheisms, wherein that which is just is the product of a singular all-powerful deity's will - but, in fairness, for example excluding some of the more mystical facets of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam … Sufis, for example, here come to mind)

The first notion makes that which is good objective - as you say, impartial to the wants or needs of individual psyches. The second notion makes that which is good contingent upon, and thereby relative to, the wants or needs of one or more psyches - such that what is good is the creation of psyches.

Furthering this a bit, in the “is thus/just is” interpretation of the good: Affinity toward this state of being is what produces moral thought and behavior. Fear of this state of being, from where are produced aversions of various types, then results in immoral (bad or evil) behavior. This then can bridge to the rather archaic - and extremely laconic - notion of ethics being reducible to either love or fear (here, implicitly, for that which just is ... unless one further equates a perfectly impartial justice/fairness/etc with love, in which case there is then either affinity toward (universal) love (and its instantiations) or fear of it).

I guess my realism is showing. -

Wayfarer

26.1kHedonism is just about what constitutes an interest — Pfhorrest

Wayfarer

26.1kHedonism is just about what constitutes an interest — Pfhorrest

Hedonism (philosophy): the ethical theory that pleasure (in the sense of the satisfaction of desires) is the highest good and proper aim of human life.

:up:

You can see the underlying logic modelled in many different cultural, philosophical and religious traditions, if you’re able to interpret them symbolically instead of simply believing. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kHedonism (philosophy): the ethical theory that pleasure (in the sense of the satisfaction of desires) is the highest good and proper aim of human life. — Wayfarer

Pfhorrest

4.6kHedonism (philosophy): the ethical theory that pleasure (in the sense of the satisfaction of desires) is the highest good and proper aim of human life. — Wayfarer

Yes, that says that pleasure is what constitutes good — so on that account looking out for everyone’s interests (aiming to do good for them) means making their lives pleasant. Hedonism doesn’t mean only looking out for your own interests, your own pleasure.

It’s about what constitutes and interest (pleasure, on a hedonist account), not about whose interests matter (just oneself, on an egotist account).

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum