-

Kym

86Ideology via a dictionary:

Kym

86Ideology via a dictionary:

"A system of ideas and ideals that form the basis of economic or political theory and policy"

"The set of beliefs characteristic of a social group or individual"

Ideology via experience:

In practice, an ideology finally distinguishes itself by its loyalty to its own values ahead of other all considerations - like facts for instance. Under pressure, an ideologue is identifiable by their rejections out-of-hand of conflicting evidences or logical critiques. Typically in preference they will attack their detractors' ethical integrity. These ad-hominum reactions can vary across a wide spectrum: From thought-blocking clichés (e.g. of "political correctness" and “bleeding hearts” from the Right) to name-calling (from "sell out" to "counter revolutionary" from the Left) to lethal violence (Fatwa-approved assassinations or the most brutal execution of heretics, by those of a more pious inclination).

It seems then that ideology is not merely a framework of ideas supporting ideals and beliefs, but is actually constructed as kind of fortress against reasoned objection, and by extension, against reality itself. While not all ideologies are so malignant, it seems that as intrinsically anti-rational constructions, all are ever prone towards a slide into the abyss.

While bracing for the shock of the next ideological train wreck, a fairly obvious question comes to mind: How best then to deal with unjust and damaging ideologies?

The relativist's plea for universal acquiescence can't be a long term solution as the world grows ever smaller - ultimately forcing the consequences of irrational value systems upon all bystanders and unfortunate ecosystems who happen to be in the way. I used to think comic derision was the most effective response until they started murdering cartoonists (thankfully my own country is merely content in jailing you for deriding the esteemed). Violence as a solution seems only to fuel the growth of conflicting ideologies - and is seldom very much fun for long. Finally, as outlined above, ideology seems specifically designed to resist critical thought and empiricism.

If philosophy can't solve the problem directly maybe it still has some good advice. I'd appreciate any practical thoughts on this problem which seems to have become more pressing. -

BC

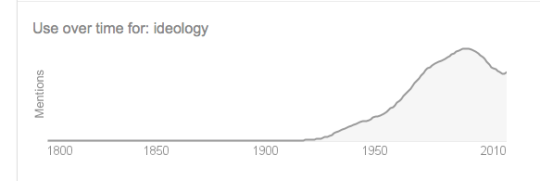

14.3kWe live in a time of "peak ideology" -- at least as far as the frequency of "ideology" in print.

BC

14.3kWe live in a time of "peak ideology" -- at least as far as the frequency of "ideology" in print.

(Google ngram)

(Google ngram)

'Ideology' has become a derogatory term, a brickbat thrown at one's opposition.

a system of ideas and ideals, especially one that forms the basis of economic or political theory and policy. "the ideology of republicanism"

synonyms: beliefs, ideas, ideals, principles, ethics, morals; More the ideas and manner of thinking characteristic of a group, social class, or individual.

"a critique of bourgeois ideology"

archaic

visionary speculation, especially of an unrealistic or idealistic nature.

the science of ideas; the study of their origin and nature. — Dictionary

Too bad it went sour, because it would otherwise be a useful word, to describe the necessary set of ideas and ideals one needs to organize one's life.

Usually ideology becomes a Maginot Line when a 'closed mind' is at work. But like the actual Maginot Line, ideology isn't a very good bulwark against one's enemies. Ideology makes one's world seem deceptively secure, and it is as long as one's enemies attack where they are supposed to, and not do an end run around one's defenses.

I find my enemies doing end runs around my ideological defenses all the time -- it's really quite annoying. Worse, they are aided by my stupid bleeding heart allies.

Philosophy should help. It really should, but it sometimes fails. Pulling in your other thread about desire, human emotions trump rational thought a good share of the time. Philosophers rely too much on the good offices of rationality. Everyone likes rationality, of course, as long as it is congenial to one's desires.

The many desires, the many powerful emotions of the animal overwhelm rationality with regularity, and it isn't enough to say we should be more rational. Ideology plus praxis is the kind of discipline we need. Lest the image of troops goose stepping along the streets of Nuremberg come to mind, that's not the kind of praxis I have in mind.

I was thinking more of the the kind of practice the ordinary good citizen deploys: volunteering time to local needs, helping neighbors in need, staying on the job and supporting one's self and family--and staying in the family, as well. Keeping informed of what is going on in the world; tending one's garden, all that stuff ordinary good citizens do.

The ordinary citizen ideologue knows that emotions do boil over at times, and either arranges a good time and place to expend the head of steam (maybe swimming laps or chopping wood) or finds a way of sublimating ones emotions for the good of civilization--a necessary and usually thankless task. -

schopenhauer1

11kI was thinking more of the the kind of practice the ordinary good citizen deploys: volunteering time to local needs, helping neighbors in need, staying on the job and supporting one's self and family--and staying in the family, as well. Keeping informed of what is going on in the world; tending one's garden, all that stuff ordinary good citizens do. — Bitter Crank

schopenhauer1

11kI was thinking more of the the kind of practice the ordinary good citizen deploys: volunteering time to local needs, helping neighbors in need, staying on the job and supporting one's self and family--and staying in the family, as well. Keeping informed of what is going on in the world; tending one's garden, all that stuff ordinary good citizens do. — Bitter Crank

The repetitively absurd tasks of existing at all. Round and round we go. Just doing stuff. Your solutions are not off from the norm: projects and community stuff. Build skills to sublimate the mind in projects and participate in community events. The stately king that belies the laughing jester showing up with diagrams of Sisyphus. -

BC

14.3kI would, of course, say what I said and you would, of course, say what you said, and we'll keep saying it most likely, because we are both ideologues. In saying that, I don't view you as any kind of enemy ideologue plotting an end run around my Maginot Line.

BC

14.3kI would, of course, say what I said and you would, of course, say what you said, and we'll keep saying it most likely, because we are both ideologues. In saying that, I don't view you as any kind of enemy ideologue plotting an end run around my Maginot Line.

You are more the type to lay a siege and employ a trebuchet to hurl depressing texts over my high walls which do, over time, minutely undermine the enthusiasm to go on living of those whose viewpoints are subject to your bombardment. I, on the other hand, project positive sounding non-inferential dramas on my walls, which lure your troops into thinking that life might possibly, perhaps, be at least slightly worthwhile, after all.

Both of us can rest, assured that nobody is much persuaded by anything we say. Hell, they're not even listening, the sons of bitches.

Alas.

The People are in la la land. "If you aren't depressed it is only because you aren't paying attention" Snark the Great said. -

schopenhauer1

11kYou are more the type to lay a siege and employ a trebuchet to hurl depressing texts over my high walls which do, over time, minutely undermine the enthusiasm to go on living of those whose viewpoints are subject to your bombardment. I, on the other hand, project positive sounding non-inferential dramas on my walls, which lure your troops into thinking that life might possibly, perhaps, be at least slightly worthwhile, after all. — Bitter Crank

schopenhauer1

11kYou are more the type to lay a siege and employ a trebuchet to hurl depressing texts over my high walls which do, over time, minutely undermine the enthusiasm to go on living of those whose viewpoints are subject to your bombardment. I, on the other hand, project positive sounding non-inferential dramas on my walls, which lure your troops into thinking that life might possibly, perhaps, be at least slightly worthwhile, after all. — Bitter Crank

Haha, I do enjoy your imagery!

Both of us can rest, assured that nobody is much persuaded by anything we say. Hell, they're not even listening, the sons of bitches. — Bitter Crank

Yep, shouting nothings into the aether.

The People are in la la land. "If you aren't depressed it is only because you aren't paying attention" Snark the Great said. — Bitter Crank

That is a great quote. -

neomac

1.6k

neomac

1.6k

I was tempted to open a thread on the same subject until I found this one. Let me revive this very old topic which I find extremely interesting.

There are some points that I gathered from the opening post and would like to comment on:

01 - Ideology as “a system of ideas and ideals that form the basis of economic or political theory and policy"

if ideology is a “system” of ideas and ideals, where ideas are about how things are (beliefs) and ideals about how things should be (norms), then those beliefs and norms are somehow interdependent. If ideology is the basis for economic/political theorising and policy, then ideology is a pre-theoretical system of ideas and ideals relevant for economy and politics.

However the pre-theoretical attitude poses an issue about their determinacy and coherence. To what extent each system of ideas and ideals can be translated into a unique list of coherent and determined beliefs and norms? On the other side, isn’t it possible that ideology as a system of ideas and ideals owes its appeal and unity not to a unique list of a determined and coherent beliefs and norms, but on something else and then we arrive at this system of ideas and ideals via abstraction from a set of a determined and coherent beliefs and norms? But doesn’t this abstraction correspond to a theoretical task or to a convenient codification which fails to account for the pre-theoretical aspect of ideology?

02 - "The set of beliefs characteristic of a social group or individual"

If ideology is characteristic of a social group, then ideology is not only a shared system of beliefs, but something that helps us identify social groups.

We can group people by their age, sexual gender, the colour of their skin, their economic status, etc. but we can group by their ideology.

But here is a link to the previous question: how far do individuals share exactly the same unique list of a determined and coherent beliefs and norms? Are people grouped by ideology after surveying their approval of a unique list of a determined and coherent beliefs and norms? Do people typically show their ideological affiliation by offering the unique list of a determined and coherent beliefs and norms which their ideology consists in?

03 - an ideologue is identifiable by their rejections out-of-hand of conflicting evidences or logical critiques. Typically in preference they will attack their detractors' ethical integrity. These ad-hominum reactions can vary across a wide spectrum: From thought-blocking clichés (e.g. of "political correctness" and “bleeding hearts” from the Right) to name-calling (from "sell out" to "counter revolutionary" from the Left) to lethal violence (Fatwa-approved assassinations or the most brutal execution of heretics, by those of a more pious inclination)

Ideology as a system of beliefs and norms resists refutation (via evidence and logic criticism) and it is “thought-blocking” (like powerful emotions), and it accompanied by intellectual or physical ad-hominem attacks. Yet even though claiming that certain beliefs or norms are refutable are not an attack ad-hominem still can challenge the credibility of the attacked. So the thought-blocking factor that accompanies ideologies seems to point to a shift of focus in the ways a set of beliefs and norms is scrutinised: from empirical evidence and logic to the credibility of the interlocutors. So not only a change in the epistemic focus but also a change in method of validation. Beliefs and norms are validated as function of the interlocutors’ credibility, in light of their interest. And the interest is identified via the system of beliefs and norms under scrutiny as convenient rationalizations of self-serving interests.

04 - It seems then that ideology is not merely a framework of ideas supporting ideals and beliefs, but is actually constructed as kind of fortress against reasoned objection, and by extension, against reality itself. While not all ideologies are so malignant, it seems that as intrinsically anti-rational constructions

Being against refutation, thought-blocking, close minded ideology is then considered anti-rational. But what do we mean by anti-rational? If the method of validation is grounded on a set of norms and beliefs, such norms and beliefs can not be refuted, since the refutation must presuppose them (like Wittgenstein’s hinge propositions). But if we do not share such norms and beliefs, and they do not ground our system of validation then of course we can refute such norms and beliefs. How do we know if we share beliefs and norms grounding our method of validation for people’s credibility?

05 - 'Ideology' has become a derogatory term, a brickbat thrown at one's opposition.

The anti-rationality of Ideology turned “ideology” into a derogatory term which is used for ad-hominem attacks against one’s opposition. So even the word “ideological” can be used ideologically! Accusing others of being “ideological” not only doesn’t make somebody immune from receiving the same accusation, but it hints at it since the subjected shifted to credibility of the interlocutor.

06 - Too bad it went sour, because it would otherwise be a useful word, to describe the necessary set of ideas and ideals one needs to organize one's life.

Interestingly, ideology despite being considered “anti-rational”, it can be also seen as accomplishing a positive function, namely offering “necessary set of ideas one needs to organise one’s life”. One may wonder why “necessary”? And how does this necessity relate to anti-rationality? Do people act anti-rationally because this set of ideas is necessary however refutable? Or considering this set of refutable beliefs as necessary is already anti-rational? “Necessary” to organise one’s life in what sense?

I think that there is a key to address my questions which would help understand ideology as something more than just an irrational behavior or derogatory term, without denying such side effects. The point is really to better understand the positive contribution of ideology in somebody’s life beyond misinformation and evil intent.

Indeed, there is a pre-theoretical dimension in everybody’s life that would make a set of beliefs and norms relevant for economic and political investigation and a the same time necessary: that’s social life. The need for trustable sociable networking in which we can fit in is what makes possible to somebody organising their life, as long as we live in society or we think ourselves as social creatures.

The need of trustable networking helps us understand better many of the features attributed to ideology:

- Ideology as a system of ideas and ideals but not in the sense of forming a unique set of beliefs and norms because for a network of people which do not necessarily share same and coherent and deep understanding of beliefs and norms what is important is to “popularize” affiliation markers like slogans, symbols and gestures that testify their “trustable” ideological affiliation (no matter how overlapping the justifications are).

- Ideology as a anti-rational behavior is clear when the issue is not to know things but to maintain the trustable network

- Ideology as an epistemic shift: credibility is important for social networking and interlocutors are provoked into taking position wrt trustability. Here the epistemic method doesn’t only change focus but also method of validation in the sense that evidence is provided through provocation (resistance from refutation and attacks ad hominem), that interlocutors provoke each other to test their trustability, their fidelity to their social network. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9k

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9k

Here's a slightly different way of looking at things.

01 - Ideology as “a system of ideas and ideals that form the basis of economic or political theory and policy"

if ideology is a “system” of ideas and ideals, where ideas are about how things are (beliefs) and ideals about how things should be (norms), then those beliefs and norms are somehow interdependent. If ideology is the basis for economic/political theorising and policy, then ideology is a pre-theoretical system of ideas and ideals relevant for economy and politics. — neomac

Under this definition, there is no distinction between ideology, and facts, as stated by the op. The facts, i.e. truths, are the ideology. It is what we believe about how things are, and how things should be.

02 - "The set of beliefs characteristic of a social group or individual"

If ideology is characteristic of a social group, then ideology is not only a shared system of beliefs, but something that helps us identify social groups. — neomac

Under this definition, we accept that there is division, disagreement as to the facts, the truth, and this division manifests as distinct social groups.

With this way of looking at things, the two definitions are consistent, and not actually describing two different things, but they are just different ways of describing the very same thing. In the first, what is described is the agreement amongst people, as to what they believe, and this constitutes their "ideology". In the second, we acknowledge that not only is there agreement amongst people as to what they believe, but their is also disagreement between people, and this produces a multitude of social groups with distinct "ideologies". So the first describes a general concept, "ideology", while the second describes what distinguishes separate, distinct and specific, ideologies. They both describe the very same thing, but the second simply adds the condition that there is not one system of ideas of how things are and how things should be, facts or truths, which everyone believes. -

Ludwig V

2.5k

Ludwig V

2.5k

The interesting question is what makes universal acquiescence impossible. I suppose it is possible that two different ideologies might be compatible, in the sense that it is possible for them to co-exist in the same society. One way is for an agreement to be struck, or worked out, which recognizes the other and makes room for them; I have in mind something rather stronger than passive toleration. One problem is the tendency for one ideology to define itself against the other.The relativist's plea for universal acquiescence can't be a long term solution — Kym

Ah, well, once we have acknowledged that we also have an ideology, we will inevitably be drawn into thinking differently about all those irrational other people. That might be very healthy, but, unless the others make the same acknowledgement, it may be rather dangerous.Too bad it went sour, because it would otherwise be a useful word, to describe the necessary set of ideas and ideals one needs to organize one's life. — BC

That is a most uncomfortable thought. What Wittgenstein regards as our ground turns out to be something quite different. My form of life, my facts turn out to be the other guy's ideology.If the method of validation is grounded on a set of norms and beliefs, such norms and beliefs can not be refuted, since the refutation must presuppose them (like Wittgenstein’s hinge propositions). — neomac

I'm consoled by the thought that what Wittgenstein was gesturing at was something shared by all human beings. If we could delineate that, we might, just might, find a basis for unity (within diversity, of course).

I think that is correct.In the first, what is described is the agreement amongst people, as to what they believe, and this constitutes their "ideology". In the second, we acknowledge that not only is there agreement amongst people as to what they believe, but their is also disagreement between people, and this produces a multitude of social groups with distinct "ideologies". — Metaphysician Undercover

I can't disagree with that, except that, at least as things are, the distinction between ideologies is extremely obscure. The lines are drawn on the level of praxis rather than intellect.So the first describes a general concept, "ideology", while the second describes what distinguishes separate, distinct and specific, ideologies. — Metaphysician Undercover -

neomac

1.6kIf the method of validation is grounded on a set of norms and beliefs, such norms and beliefs can not be refuted, since the refutation must presuppose them (like Wittgenstein’s hinge propositions). — neomac

neomac

1.6kIf the method of validation is grounded on a set of norms and beliefs, such norms and beliefs can not be refuted, since the refutation must presuppose them (like Wittgenstein’s hinge propositions). — neomac

That is a most uncomfortable thought. What Wittgenstein regards as our ground turns out to be something quite different. My form of life, my facts turn out to be the other guy's ideology.

I'm consoled by the thought that what Wittgenstein was gesturing at was something shared by all human beings. If we could delineate that, we might, just might, find a basis for unity (within diversity, of course). — Ludwig V

The fact that there are beliefs universally shared doesn't spare us from the predicament of non-shared beliefs. And attributing these non-shared beliefs to evil intentions or stupidity (or ideology, in a derogatory sense) shows an ideological attitude which can suffer from analogous accusations. -

neomac

1.6kHere's a slightly different way of looking at things.

neomac

1.6kHere's a slightly different way of looking at things.

01 - Ideology as “a system of ideas and ideals that form the basis of economic or political theory and policy"

if ideology is a “system” of ideas and ideals, where ideas are about how things are (beliefs) and ideals about how things should be (norms), then those beliefs and norms are somehow interdependent. If ideology is the basis for economic/political theorising and policy, then ideology is a pre-theoretical system of ideas and ideals relevant for economy and politics. — neomac — Metaphysician Undercover

Where is it stated that there is no distinction between ideology and facts?

Claiming that Ideology is “a system of ideas and ideals that form the basis of economic or political theory and policy" doesn’t imply any equation between facts and ideology.

“Facts” refers to what ideological beliefs are about.

Under this definition, we accept that there is division, disagreement as to the facts, the truth, and this division manifests as distinct social groups.

With this way of looking at things, the two definitions are consistent, and not actually describing two different things — Metaphysician Undercover

No idea what the purpose of your remark is since I never claimed that the 2 quotes talk about different things or about the same thing but inconsistently.

What I was trying to do is to elaborate those 6 points reported in the opening post to offer a certain understanding of the link between the “irrationality” of ideologies and yet their necessity. Ideologies shape our pre-theoretical beliefs and norms in ways that are functional to social grouping and collective action. That’s why the value of ideologies is NOT in their offering a unique and consistent set of beliefs universally shared by those who adopt a certain ideology (that’s why “falsity”, “inconsistency”, “partiality”, “indeterminacy” are more easily tolerated). Which, in turn, offers a criterium of epistemic validation that bypasses those methods considered “rational”.

Indeed, even those “rational” methods presuppose ideologies (like that one of the Enlightenment) if they have to be promoted at social level and inform communities. -

Ludwig V

2.5kquote="neomac;1000226"]The fact that there are beliefs universally shared doesn't spare us from the predicament of non-shared beliefs. And attributing these non-shared beliefs to evil intentions or stupidity (or ideology, in a derogatory sense) shows an ideological attitude which can suffer from analogous accusations.[/quote]

Ludwig V

2.5kquote="neomac;1000226"]The fact that there are beliefs universally shared doesn't spare us from the predicament of non-shared beliefs. And attributing these non-shared beliefs to evil intentions or stupidity (or ideology, in a derogatory sense) shows an ideological attitude which can suffer from analogous accusations.[/quote]

I agree with all of that. I was, rather, suggesting that what we can agree on might be a basis for working out a way of co-existing in spite of the things we do not agree on.

After all, different ideologies will either compete or co-exist, and we might all do better if we worked as hard at co-existing as we do at competing. -

Joshs

6.7kIf the method of validation is grounded on a set of norms and beliefs, such norms and beliefs can not be refuted, since the refutation must presuppose them (like Wittgenstein’s hinge propositions). But if we do not share such norms and beliefs, and they do not ground our system of validation then of course we can refute such norms and beliefs — neomac

Joshs

6.7kIf the method of validation is grounded on a set of norms and beliefs, such norms and beliefs can not be refuted, since the refutation must presuppose them (like Wittgenstein’s hinge propositions). But if we do not share such norms and beliefs, and they do not ground our system of validation then of course we can refute such norms and beliefs — neomac

If another group’s norms and beliefs don’t ground our system of validation, then we can’t refute those norms and beliefs because we won’t be able to understand them. Refutation only makes sense when it is based on normative criteria provided by the same Wittgensteinian hinge proposition as that which is to be refuted. -

180 Proof

16.5k

180 Proof

16.5k

I.e. common sense (socialization aka "ideology") can be corrected, or coarse-grained, by science (observations + experiments) that in turn, through reflection (critique / dialectics), can be corrected, or biases exposed, by philosophy. "And so on and so on ..." :smirk: -

Ludwig V

2.5k

Ludwig V

2.5k

That's not quite right. Obviously, if you want to refute a belief in order to persuade the believer to give up their belief, then you must, as it were, speak to/with their norms and beliefs. But it is perfectly possible to refute someone's belief to one's own satisfaction without speaking to them at all. I mention this because I suspect that situation arises much more frequently than it ought to. BTW, it may seem a bit pointless to refute someone's beliefs only to one's own satisfaction, but there is a point. You prevent the other side recruiting your own followers, which is much more important than convincing the opposition.If another group’s norms and beliefs don’t ground our system of validation, then we can’t refute those norms and beliefs because we won’t be able to understand them. Refutation only makes sense when it is based on normative criteria provided by the same Wittgensteinian hinge proposition as that which is to be refuted. — Joshs

On the other hand, there is a process of - let me call it - conversion. Communists becoming capitalists and even vice versa. So far as I can see, this is not, and cannot be, a rational process. Certainly psychologists have taken an interest in it - no doubt for practical reasons. This is extremely uncomfortable for philosophers. Sadly, I'm going to have to leave that there - I'm falling asleep as I write, which is not a good way to philosophize. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kI can't disagree with that, except that, at least as things are, the distinction between ideologies is extremely obscure. The lines are drawn on the level of praxis rather than intellect. — Ludwig V

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kI can't disagree with that, except that, at least as things are, the distinction between ideologies is extremely obscure. The lines are drawn on the level of praxis rather than intellect. — Ludwig V

I think any boundaries between distinct ideologies are theoretical and made for a purpose. Consider, that no two people really share all their believes, so in that sense we could say that everyone has one's own distinct ideology. But on the other hand, if we limit a particular "ideology" to just a small set of very. general ideas, then many people have the same ideology. So the drawing of lines between ideologies is complex and purposeful, yet somewhat arbitrary. -

Ludwig V

2.5k

Ludwig V

2.5k

That seems to be right. Given the hostility that there so often is between ideologies, I would expect that to be a major factor in how people decide to draw the lines.I think any boundaries between distinct ideologies are theoretical and made for a purpose. Consider, that no two people really share all their believes, so in that sense we could say that everyone has one's own distinct ideology. But on the other hand, if we limit a particular "ideology" to just a small set of very. general ideas, then many people have the same ideology. So the drawing of lines between ideologies is complex and purposeful, yet somewhat arbitrary. — Metaphysician Undercover -

neomac

1.6kIf another group’s norms and beliefs don’t ground our system of validation, then we can’t refute those norms and beliefs because we won’t be able to understand them. — Joshs

neomac

1.6kIf another group’s norms and beliefs don’t ground our system of validation, then we can’t refute those norms and beliefs because we won’t be able to understand them. — Joshs

Adopting certain beliefs and norms as conditions for validation, already implies refusing to adopt other beliefs and norms as conditions for validation. And as long as beliefs and norms do not enjoy a special status of conditions for validation, then they can be scrutinised in light of beliefs and norms adopted as conditions for validation, and possibly refuted. So I get that mutual understanding presupposes shared assumptions. But ideological refutation is based on non-shared assumptions, so shared assumptions is not a requirement for ideological refutation. And any attempt to consider alternative beliefs and norms as ground for validation is taken to be a form of “rationalization” or “opium” (lack of loyalty is sort of conflated with lack of intellectual honesty).

To be more clear, what is peculiar in the case of ideology from an epistemological point of view is that there is a double epistemic shift: epistemic target (we are not interested in what claimed beliefs tells us about facts, but what they tell us about the subject making those claims, and not even as individuals but as group representatives) and of method of validation (a claim is validated or refuted in light of group affiliation) both of which are inherent to social grouping.

Let’s discuss concrete examples: to me, beliefs such as “the US has provoked Russia into the Ukrainian conflict” or “Israel is committing a genocide in Gaza” or “Western Capitalism is the cause of social inequalities in the World” or “owning nuclear bombs is in the best national interest of Iran” or “Trump is a real patriot” are ideological NOT to the extent they (in)accurately describe or assess certain facts. Their ideological value is not grounded in their accuracy (their accuracy may even contribute to a loss in ideological relevance) but in their aptness to work as polarising social markers for an in-group vs un out-group discrimination (which doesn’t even need to pre-exist!) and possible mobilisation. Thinking ideologically is engaging in a primitive game for social grouping. Its necessity comes from being integral part of our social life, especially beyond interpersonal relations. Its “irrationality” comes from the fact we are capable of thinking non-ideologically as long as we do not feel pressed by social life. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kGiven the hostility that there so often is between ideologies, I would expect that to be a major factor in how people decide to draw the lines. — Ludwig V

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kGiven the hostility that there so often is between ideologies, I would expect that to be a major factor in how people decide to draw the lines. — Ludwig V

Hostility, in relation to ideology, is very interesting. We can look at it in two different ways, hostility as caused by an ideological difference, and hostility as the cause pf ideological difference. Often, we are inclined to take the simple way of looking at things, and assume that a specific case of hostility is the result of a difference in ideology. This results in each side being rational, yet with distinct ideas about what is true and good. However, since we must accept the reality that people actually draw these lines, which constitute separations in ideology, the matter is much more complex, as hostile action will induce the creation of a boundary.

The issue I believe, is that hostility is related to actions, and actions are not always driven by ideology. There are many different types of causes related to human actions, from reflex, intuition, irrational passions, through to ideological principles. So many actions which create hostility are derived from irrational sources, and only the ones which can be traced to some specific ideology can be described as rational. Because of this, many hostilities have an irrational source, and this justifies the exclusion of the purveyors of such actions from ones ideology. In other words, the ideology is designed so as to exclude the others as acting from an irrational source. The others are portrayed as savages, and whatever ideology they are acting on must be distinctly unacceptable, impossible to understand, as irrational. -

Ludwig V

2.5k

Ludwig V

2.5k

Quite right. Well put.

It's odd, isn't it, how people yearn for peace when they don't have it, and cannot resist starting a conflict when they do? There seems no way of changing that. -

neomac

1.6kI.e. common sense (socialization aka "ideology") can be corrected, or coarse-grained, by science (observations + experiments) that in turn, through reflection (critique / dialectics), can be corrected, or biases exposed, by philosophy. "And so on and so on ..." :smirk: — 180 Proof

neomac

1.6kI.e. common sense (socialization aka "ideology") can be corrected, or coarse-grained, by science (observations + experiments) that in turn, through reflection (critique / dialectics), can be corrected, or biases exposed, by philosophy. "And so on and so on ..." :smirk: — 180 Proof

I disagree with both you and Zizek.

Science can correct beliefs to the extent there is TRUST in science and within science, but science can be easily trapped in ideological struggles as well, as we have seen in the debate about covid and climate change. As I argued, ideologies have less to do with knowledge of facts and more to do with knowledge of social groups.

What you call reflection, critique, dialecticts, "And so on and so on ..." is often nothing more than validating or refuting the ideology of somebody else in light of the ideology one supports.

Also the psychological understanding of ideology offered by Zizek is missing the point. Ideologies are not glasses that distort reality accessible without glasses. Social groupings are inaccessible without ideological glasses. -

neomac

1.6kI was, rather, suggesting that what we can agree on might be a basis for working out a way of co-existing in spite of the things we do not agree on.

neomac

1.6kI was, rather, suggesting that what we can agree on might be a basis for working out a way of co-existing in spite of the things we do not agree on.

After all, different ideologies will either compete or co-exist, and we might all do better if we worked as hard at co-existing as we do at competing. — Ludwig V

I just realized I missed a comment of yours to my quote. I do not disagree with your general claims but they do not offer any concrete path toward peaceful coexistence. And even the belief of the possible co-existence of potentially competing ideologies can be trapped in ideological struggles. Often competing ideologies can converge when there is a third ideology perceived as common threat (like extreme left and Islamism occasionally converging in their criticism against Western capitalism, or christianity and capitalism converging in opposing the communist ideology, etc.). -

Ludwig V

2.5k

Ludwig V

2.5k

There's so much going on that it is very hard to keep up with everything. I'm afraid I don't even try.I just realized I missed a comment of yours to my quote — neomac

There's a reason why I'm not. I oscillate between thinking that if only everybody would play nice, how much better it would be and thinking that we need someone even heavier than the heavies we have to knock heads together. Neither suggestion is particularly helpful, I know.I do not disagree with your general claims but they do not offer any concrete path toward peaceful coexistence. — neomac

There is also a part of me that thinks that the perpetual struggle is how it is. Sruggle may take different forms from time to time, but there is always struggle.

Yes, the enemy of my enemy is my friend - at least until our common enemy is defeated, when any thing may happen. One of the differences between our situation now and the situation up to about 2000 is that we no longer live in a world with just one dominating struggle, but a multi-polar, multi-struggle world. Whether that's better or worse, I wouldn't like to say.Often competing ideologies can converge when there is a third ideology perceived as common threat — neomac

Human beings are very strange. Sometimes they will sink their differences to deal with a common enemy. Sometimes they fall apart and fight each other instead of dealing with the common enemy. Climate change is an example of the latter, unfortunately. -

Joshs

6.7k

Joshs

6.7k

Adopting certain beliefs and norms as conditions for validation, already implies refusing to adopt other beliefs and norms as conditions for validation. And as long as beliefs and norms do not enjoy a special status of conditions for validation, then they can be scrutinised in light of beliefs and norms adopted as conditions for validation, and possibly refuted. So I get that mutual understanding presupposes shared assumptions. But ideological refutation is based on non-shared assumptions, so shared assumptions is not a requirement for ideological refutation — neomac

One dictionary definition of ‘refute’ is: to prove (a statement or theory) to be wrong or false; disprove. If you accept this definition as consistent with your use of the word, then to refute is to access a vantage beyond ideology, an objective meta-position that transcends bias. In the philosophical literature one can find critiques of ideology from the left and the right. Critiques from the left tend to locate the concept of ideology with Marxist discourses. One can find such critiques among postmodern and poststructuralist writers. What they object to about the analysis of social configurations of knowledge in terms of ideology is not its assumption that knowledge is socially constructed, but that it can be totalized on the basis of a logic of development, that it moves toward an ultimate end.

What the leftist critics of ideology keep from Marxism ( and Hegelianism) is the notion that knowledge is only produced within social formations, and the development of these formations does not proceed by way of refutation but revolutionary transformation. Common to Wittgenstein’s forms of life and hinges , Heidegger’s worldviews, Foucault’s epistemes and Kuhn’s paradigms is a rejection of the idea that social formations of knowledge progress via refutation. It sounds like your critique of ideology is from the right, which places it as a pre-Hegelian traditionalist thinking. -

neomac

1.6k

neomac

1.6k

.One dictionary definition of ‘refute’ is: to prove (a statement or theory) to be wrong or false; disprove. If you accept this definition as consistent with your use of the word, then to refute is to access a vantage beyond ideology, an objective meta-position that transcends bias — Joshs

The definition of “to refute” doesn’t tell us what beliefs are true or false, proven or unproven, biased or unbiased. It doesn’t even offer us a method for proving anything.

Nor claiming something to be proven to be right or wrong, refuted or validated makes it right or wrong, successfully proven or refuted.

What I’m contending is that ideological thinking consists precisely in validating and refuting (potentially any) normative or factual claims in light of social affiliations that such normative or factual claims hint at. This way of thinking MAY be claimed to be biased having in mind stricter procedures oriented to maximise factual knowledge (scientific, legal, professional reporting, etc.) instead of grouping living social interactions. Yet I’m contending that NONE of such procedures can replace ideological thinking to the extent ideology is the pre-theoretical form of social grouping. On the contrary, scientific, legal, professional reporting practices presuppose supporting ideologies for such practices to thrive and inform social life. Indeed, all these procedures can as well be compromised by ideological struggles.

.In the philosophical literature one can find critiques of ideology from the left and the right. Critiques from the left tend to locate the concept of ideology with Marxist discourses. One can find such critiques among postmodern and poststructuralist writers. What they object to about the analysis of social configurations of knowledge in terms of ideology is not its assumption that knowledge is socially constructed, but that it can be totalized on the basis of a logic of development, that it moves toward an ultimate end — Joshs

My readings about ideology mainly include De Stutt, Napoleon, Marx, Althusser and Mannheim. I think Althusser is making a similar point. But I don’t find his way of arguing sharp enough.

.What the leftist critics of ideology keep from Marxism ( and Hegelianism) is the notion that knowledge is only produced within social formations, and the development of these formations does not proceed by way of refutation but revolutionary transformation — Joshs

That is not in conflict with what I said of ideology. Indeed, if refutation is based on non-shared assumptions there is no way to dialectically persuade those who do not share those assumptions with arguments based on those assumptions. Under this predicament, if we want them to act in accordance to our views, then we are left with the only option of imposing our views on them by brute force (or treachery?). But if we feel JUSTIFIED in doing this, this is because we take our views to be the valid ones, and their views the invalid ones.

.Common to Wittgenstein’s forms of life and hinges , Heidegger’s worldviews, Foucault’s epistemes and Kuhn’s paradigms is a rejection of the idea that social formations of knowledge progress via refutation — Joshs

You read my posts having in mind certain views of knowledge progress and related ways of phrasing the issue. But those views do not seem to me really focused on what I’m focusing on, not even relevant to question anything I said.

It sounds like your critique of ideology is from the right, which places it as a pre-Hegelian traditionalist thinking. — Joshs

No idea what you are referring to. Feel free to quote those pre-Hegelian traditionalist or critique of ideology from the right you find closer to my views. -

BC

14.3kTrue. "Inflexibility" in belief is a problem. It hobbles one's capacity to deal with a world which is always more complex and contradictory than ideology allows. I don't usually associate Christian preaching with 'ideology', but some varieties of Christian teaching are extremely rigid and inflexible.

BC

14.3kTrue. "Inflexibility" in belief is a problem. It hobbles one's capacity to deal with a world which is always more complex and contradictory than ideology allows. I don't usually associate Christian preaching with 'ideology', but some varieties of Christian teaching are extremely rigid and inflexible.

I'll also grant that some of the ideology I have read and spouted at times was undermined by its inflexibility and, sometimes, it was just plain wrong. -

Joshs

6.7k

Joshs

6.7k

if refutation is based on non-shared assumptions there is no way to dialectically persuade those who do not share those assumptions with arguments based on those assumptions. Under this predicament, if we want them to act in accordance to our views, then we are left with the only option of imposing our views on them by brute force (or treachery?). But if we feel JUSTIFIED in doing this, this is because we take our views to be the valid ones, and their views the invalid ones. — neomac

Why are these the only two options? Why couldn't I teach someone a different way of looking at world, the way which grounds my own arguments and facts, so that they can understand the basis of my criteria of justification? It would not be a question of justifying the worldview I convert them to, but of allowing them to justify the arguments and views that are made intelligible from within that worldview.

Men have believed that they could make the rain; why should not a king be brought up in the belief that the world began with him? And if Moore and this king were to meet and discuss, could Moore really prove his belief to be the right one? I do not say that Moore could not convert the king to his view, but it would be a conversion of a special kind; the king would be brought to look at the world in a different way. ( Wittgenstein, On Certainty) -

neomac

1.6kWhy are these the only two options? — Joshs

neomac

1.6kWhy are these the only two options? — Joshs

My bad, I was too hasty in drawing that conclusion. What I should have said instead is that once persuasion is not achievable on shared normative/epistemic assumptions, one can try to induce a compliant behavior in others by other means and incentives, which can include also brute force. But, I guess, this is still far from what you are hinting at in the following quote.

Why couldn't I teach someone a different way of looking at world, the way which grounds my own arguments and facts, so that they can understand the basis of my criteria of justification? It would not be a question of justifying the worldview I convert them to, but of allowing them to justify the arguments and views that are made intelligible from within that worldview. — Joshs

I have no problems at admitting this possibility too. We acquire ideologies mostly through education (aka Althusser’s ideological apparatuses) and my argument doesn’t concern our educational dispositions as learners or teachers. We shouldn’t also discount the fact that training others to view things differently may include also pain and coercion (BTW Zizek, in that video, is giving a psychological explanation for why liberation from one own’s ideology needs to be forced on people). And history, up until nowadays, has offered abundant examples of coercion ideologically induced.

Nor am I questioning our capacity of non-ideological thinking. And our intellectual dispositions to adopt a reflective, critical or theoretical approach toward our own ideological views.

Nor am I excluding many other factors contributing to ideological shifts in a population: like material and technological evolution, demographic and generational change, historical traumas, etc.

To me these are all interesting empirical questions, focusing on cultural shifts or cultural sophistication.

My argument however is more conceptual (what is “ideology”?). In particular, my conception provides a certain understanding of the link between “necessity” and “irrationality” of ideological thinking as discussed in the opening post, and distances itself from more psychological understanding of ideologies (evil intentions, stupidity, comforting delusions ) which I find rather misleading (if not even, ideologically motivated!). The problem ideologies respond to is very basic and very unescapable. Societies are elusive entities not only because the complexity and dynamism of social interactions and their aggregated results can vastly exceed our direct personal experience and computational capacity as individuals, but also because with our actions and beliefs we are integral part of society (aka there is no separation between subject and object of knowledge). So ideology is the most basic form of coordination for social grouping to support a given informational flow within a society and political mobilisation. Under enough social pressure, anybody can be compelled to engage in ideological thinking whatever their intellectual, moral or emotional dispositions may otherwise be.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum