-

prothero

514

prothero

514

This just sounds like Kant's noumena, phenomena dichotomy or the repetitive discussions of indirect versus direct realism.. Sure our worldview is strongly shaped by our culture, our language, our limited sense perception and the way in which our mind integrates and presents sense data to us. I just don't see how that makes a reality independent of human minds any less "real" or "existent". It is our limitation not a limitation on reality independent of our minds and thoughts.

It seems like a tautology to see our minds create our reality but begs the question of a reality independent of our minds. -

Wayfarer

26.1kThis just sounds like Kant's noumena, phenomena dichotomy or the repetitive discussions of indirect versus direct realism.. Sure our worldview is strongly shaped by our culture, our language, our limited sense perception and the way in which our mind integrates and presents sense data to us. I just don't see how that makes a reality independent of human minds any less "real" or "existent". It is our limitation not a limitation on reality independent of our minds and thoughts.

Wayfarer

26.1kThis just sounds like Kant's noumena, phenomena dichotomy or the repetitive discussions of indirect versus direct realism.. Sure our worldview is strongly shaped by our culture, our language, our limited sense perception and the way in which our mind integrates and presents sense data to us. I just don't see how that makes a reality independent of human minds any less "real" or "existent". It is our limitation not a limitation on reality independent of our minds and thoughts.

It seems like a tautology to see our minds create our reality but begs the question of a reality independent of our minds. — prothero

You're correct that the distinction between how reality appears to us (phenomena) and a supposed reality in itself (noumena) is central to Kant, and I acknowledge that my argument certainly draws from that lineage.

However, dismissing it as "just" those things misses the specific nuance and also the validation from cognitive science that I'm emphasizing. It's not simply a philosophical rehashing; it's showing how our modern understanding of cognition lends empirical weight to these philosophical insights. In fact, scholars like Andrew Brook, who has written extensively on Kant and cognitive science, highlight these very connections between Kant's insights and current cognitive science. I'm intending to show how our modern understanding of cognition lends weight to these philosophical insights, going beyond a mere rehashing of past debates.

As to 'not being able to see' - the very act of seeing (or not seeing) draws on the mind's structuring capacities. The thought experiment of picturing a scene from "no point of view" highlights this: our attempts to describe even an unseen reality always, implicitly or explicitly, reintroduce a perspective. It's not merely that our minds are limited in grasping an already-structured external reality. It's that the structure itself (the segmentation into "objects," the experience of "color" or "sound") arises from the interaction between the world and the mind's organizing principles. This doesn't make what we regard as 'external reality' any less than real - rather, it's to point out that its reality-as-known or reality-as-intelligible is co-constituted by mind. Self and world are co-arising, neither exists in any absolute sense.

I get your objection, it's the one that everybody has: the world is there anyway, regardless of whether we're in it or see it or not. And we rely on that for our sense of orientation to the world, we are kind of reassured by it. But this is the philosophy of 'the subject who forgets himself', to put it in Schopenhauer's terms, an insight that has been subsequently elaborated by phenomenology and existentialism. Again, I'm not saying that the world exists in your or my mind: what I'm arguing is that what we understand as the world has an inextricably subjective element, which is provided by the observer, and outside of which, nothing can be said to exist or not exist. -

boundless

742So what form of idealism is being promoted? What does this form of idealism have to say about cosmology (14 billion year old universe, 5 billion year old solar system and all the time before advanced or organized minds existed?) Or even the process of evolution. I just can't see how the notion that everything is just minds and mental contents, survives the modern scientific view of the world we live in.? — prothero

boundless

742So what form of idealism is being promoted? What does this form of idealism have to say about cosmology (14 billion year old universe, 5 billion year old solar system and all the time before advanced or organized minds existed?) Or even the process of evolution. I just can't see how the notion that everything is just minds and mental contents, survives the modern scientific view of the world we live in.? — prothero

The problem with 'idealism' is that there are different forms of it and under that names are included views that are incompatible with each others.

If we restrict to the 'strict' ontological idealism that I talked about before - that is everything is either 'minds' or 'mental contents' - then, of course, you have to posit something additional to what we observe 'in this world'. Berkeley, for instance, would probably respond that God's creative and sustaining activities are what guarantee the validity of scientific theories, at least from a phenomenological and practical level.

Other ontological idealists that are not so strict and affirm the existence of the material/physical world nevertheless accept the idea that the 'mental' is more independent from the 'material'. So, of course, something mental must have existed before the coming into being of life and mind as we know it.

But, anway, even if something like Democritus' atomism - i.e. reductionist materialisms - were true then scientific theories like evolution would be only provisionally true. After all, if at the ultimate level there are only the fundamental consitituents of matter and everything else - like cells, DNA, mountains, animals, humans etc - are reducible to those consituents, it seems evident to me that a theory like evolution would not be ultimately true, but only pragmatically/transactionally true. Why? Because under such reductionist models, there are, ultimately, no DNA, cells, humans, animals etc. So you can't take the theory of biological evolution as a literal picture of 'reality as it is'. You can still speak about its practical usefulness, its ability to make predictions and so on but you have to renounce to treat it as a correct depiction of 'what really happens'.

So, I guess that, ironically, the most strict forms of materialism - i.e. reductionist materialisms - actually have to treat these things in a similar way as they are treated by strict ontological idealism. -

Mww

5.4k….not being able to say (?):…seems like a tautology to

Mww

5.4k….not being able to say (?):…seems like a tautology tosee(say) our minds create…. — prothero

How can a metaphysical project, the theme of which is the set of necessary conditions for a theoretical method of empirical human knowledge, have contained in it as central to that theme, that which is systemically impossible to know anything about?

Given such thematic major premise, it follows as a matter of course that….

…..phenomena/noumena is a false dichotomy;

…..by definition, the mind cannot create reality;

…..a supposed reality in itself is a methodological, systemic, contradiction.

But then, times have changed, pick the predicates of one or of another, but to co-mingle them destroys both. -

prothero

514As to 'not being able to see' - the very act of seeing (or not seeing) draws on the mind's structuring capacities. The thought experiment of picturing a scene from "no point of view" highlights this: our attempts to describe even an unseen reality always, implicitly or explicitly, reintroduce a perspective. It's not merely that our minds are limited in grasping an already-structured external reality. It's that the structure itself (the segmentation into "objects," the experience of "color" or "sound") arises from the interaction between the world and the mind's organizing principles. This doesn't make what we regard as 'external reality' any less than real - rather, it's to point out that its reality-as-known or reality-as-intelligible is co-constituted by mind. Self and world are co-arising, neither exists in any absolute sense. — Wayfarer

prothero

514As to 'not being able to see' - the very act of seeing (or not seeing) draws on the mind's structuring capacities. The thought experiment of picturing a scene from "no point of view" highlights this: our attempts to describe even an unseen reality always, implicitly or explicitly, reintroduce a perspective. It's not merely that our minds are limited in grasping an already-structured external reality. It's that the structure itself (the segmentation into "objects," the experience of "color" or "sound") arises from the interaction between the world and the mind's organizing principles. This doesn't make what we regard as 'external reality' any less than real - rather, it's to point out that its reality-as-known or reality-as-intelligible is co-constituted by mind. Self and world are co-arising, neither exists in any absolute sense. — Wayfarer

I always have had trouble with philosophical skepticism (especially solipsism) and any form of absolute idealism, even to the point of refusing to seriously entertain the premise or spend considerable time or effort to follow the argument.

I would agree the division of the world into individual objects with inherent properties is a product of mind not of nature. There are no independent objects (everything arises from and is dependent upon) the larger world and environment and properties are really just relationships between events. In that sense the world as we imagine it to be and the way we talk about it are just products or our minds and sense perceptions. The post modernist critique of all our notions about truth and history being products or our language and culture have some validity.

I would also agree that our thoughts, feelings and perceptions are just as much a part of reality and nature as the atoms and fundamental physical forces that we create language and concepts to talk about. The warmth of the sunset and the red sky are as real as the infrared and wavelengths of light we use to talk about them. They are all part of nature, you can not pick and choose.

In the end it seems clear that there is a world, reality, universe which carries on with or without us and which is really quite oblivious to our conceptions and which will obliterate us (and thus our minds, perceptions and thoughts) if we get too carried away with the notion the we create reality as opposed to just living in it, temporarily and contingently :smile: . -

Wayfarer

26.1kIn the end it seems clear that there is a world, reality, universe which carries on with or without us and which is really quite oblivious to our conceptions and which will obliterate us (and thus our minds, perceptions and thoughts) if we get too carried away with the notion the we create reality as opposed to just living in it, temporarily and contingently — prothero

Wayfarer

26.1kIn the end it seems clear that there is a world, reality, universe which carries on with or without us and which is really quite oblivious to our conceptions and which will obliterate us (and thus our minds, perceptions and thoughts) if we get too carried away with the notion the we create reality as opposed to just living in it, temporarily and contingently — prothero

It's not a matter of being carried away. It's an antidote to having been carried away by the belief...

...that Man is the product of causes which had no prevision of the end they were achieving; that his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, his loves and his beliefs, are but the outcome of accidental collocations of atoms; that no fire, no heroism, no intensity of thought and feeling, can preserve an individual life beyond the grave; that all the labours of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all the noonday brightness of human genius, are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system, and that the whole temple of Man’s achievement must inevitably be buried beneath the débris of a universe in ruins—all these things, if not quite beyond dispute, are yet so nearly certain, that no philosophy which rejects them can hope to stand. Only within the scaffolding of these truths, only on the firm foundation of unyielding despair, can the soul’s habitation henceforth be safely built. — Bertrand Russell, A Free Man's Worship

The mistake is to situate, or confine, 'the soul' to that context to begin with. What if the entire spectacle were to exist in the soul, rather than vice versa?

We are accustomed nowadays to thinking of ourselves as 'the outcome' or 'the product of' material causation, the accidental byproducts of an entirely fortuitous chain of events. Historically, idealism arose as a criticism and protest against that, the observation that whilst physically h.sapiens is a mere blip in the vastness of cosmic time, nevertheless it is us who are aware of that vastness, we are the form in which it becomes aware of itself. -

prothero

514We are accustomed nowadays to thinking of ourselves as 'the outcome' or 'the product of' material causation, the accidental byproducts of an entirely fortuitous chain of events. Historically, idealism arose as a criticism and protest against that, the observation that whilst physically h.sapiens is a mere blip in the vastness of cosmic time, nevertheless it is us who are aware of that vastness, we are the form in which it becomes aware of itself. — Wayfarer

prothero

514We are accustomed nowadays to thinking of ourselves as 'the outcome' or 'the product of' material causation, the accidental byproducts of an entirely fortuitous chain of events. Historically, idealism arose as a criticism and protest against that, the observation that whilst physically h.sapiens is a mere blip in the vastness of cosmic time, nevertheless it is us who are aware of that vastness, we are the form in which it becomes aware of itself. — Wayfarer

It should be pretty clear that I do not subscribe to Russell's view of our role in nature. Since my particular view of the divine is one of striving towards creativity, experience, novelty and complexity. That is not to say that there is not a "reality" separate from us or that we are the intended "result" of the divine which dwells within, merely that we (with all our thought, perception and experiences) are part of nature, not separate from the world in which we arise and on which we depend. To separate the world into primary and secondary qualities like Locke is to make an artificial bifurcation of nature. To think that our mathematical models are nature is to commit a fallacy of misplaced concreteness and to think that space and time are separate from process and events is the fallacy of simple location.

I don't really see idealism as the proper solution to eliminative materialism (scientific materialism) although it does get one thinking along a better trajectory. -

Wayfarer

26.1kIt should be pretty clear that I do not subscribe to Russell's view of our role in nature. — prothero

Wayfarer

26.1kIt should be pretty clear that I do not subscribe to Russell's view of our role in nature. — prothero

I didn't think that you would. My point was that the view that Russell expresses in that essay, is what Kant's form of idealism was a remedy for.

I've read a little of Whitehead 'science in the modern world' and other snippets. I'm generally on board with it, but struggle with his 'actual occasions' and pan-experientialism. -

prothero

514

prothero

514

Well, for Whitehead "actual occasions" (drops of experience) are the final actualities of which reality is composed. Apart from them there is vast nothingness. As for panexperientialism, panpsychism is becoming a respectable view in the philosophy of mind and consciousness and the view that Whiteheads events (which create time and space) have both a experiential and a physical aspect fits into that quite well. Whitehead is well worth more of your time,, I think. Not contrary to Buddhist philosophy just different concepts and language. The divine dwells within the processes of nature. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI always have had trouble with philosophical skepticism (especially solipsism) and any form of absolute idealism, even to the point of refusing to seriously entertain the premise or spend considerable time or effort to follow the argument. — prothero

Wayfarer

26.1kI always have had trouble with philosophical skepticism (especially solipsism) and any form of absolute idealism, even to the point of refusing to seriously entertain the premise or spend considerable time or effort to follow the argument. — prothero

Incidentally, I don't regard the view I'm arguing for as necessarily skeptical, in the sense that I don't take issue with established scientific hypotheses. I'm not claiming that scientific knowledge is illusory or fallacious. The principle I'm arguing against, is the idea that mind-independence is a criterion of what can be considered real, in regards to objects of perception and cognition. The problem with it is that perception of objects is itself contingent upon our perceptual and cognitive faculties, and in that important sense, objects are not 'mind-independent', even if, in another sense, they exist independently of us.

This was the philosophical point behind the famous Bohr-Einstein debates that occupied them for decades. While there are many complexities in those debates, the fundamental point was Einstein's insistence of the mind-independence of the objects of physics, 'otherwise', he said, 'I don't know what physics is meant to be about'. Bohr, on the other hand, wasn't being a solipsist or skeptic. His point was more nuanced: the conditions under which sub-atomic phenomena appear are not separable from the means of observation and measurement. As he put it, “Physics is not about how the world is, it is about what we can say about the world.” This reflects a kind of epistemological modesty, not a sweeping skepticism.

As regards absolute idealism - we had a thread at the beginning of this year on a current German philosopher, very much in the lineage of German idealism, Sebastian Rödl, Professor of Practical Philosophy at Leipzig University and an advocate of absolute idealism, associated with G W Hegel:

“According to Hegel, being is ultimately comprehensible only as an all-inclusive whole (das Absolute). Hegel asserted that in order for the thinking subject (human reason or consciousness) to be able to know its object (the world) at all, there must be in some sense an identity of thought and being.”

His book is Self-Consciousness and Objectivity: an Introduction to Absolute Idealism. And it was one tough read. We got through the first few sections, but discussion petered out, as his focus was so intense and specific. -

prothero

514Does anybody really support mind-independent reality? The question in the opening post?

prothero

514Does anybody really support mind-independent reality? The question in the opening post?

"does the moon still exist when not being observed?" part of the Einstein/Bohr debate

The answer as lawyers would say "it depends" on how one defines the meaning of the words and concepts.

Is the reality that we observe and experience, Mind independent, probably not. For our experience of the word is filtered through our senses and organized into patterns by our brains. Our picture or representation of reality is good enough for our survival and our procreation which evolutionarily is all that is required. Other creatures can see wavelengths we can not and hear frequencies we can not because such capabilities enhance their survival and procreation. Their picture of the world is different from ours so one could say they experience a reality different from ours, but probably better stated they experience "reality" in a different way (avoiding a certain ambiguity of language)..

All of this is pretty basic science and physiology of perception along with neuroscience and cognition. Arguing whether our experience of the world is direct or indirect,, mind independent or mind created in some ways seems beside the point, as long as you understand cognition and perception.

What is the nature of reality apart from us or apart from our mind and experience. That seems like the question of noumena versus phenomena and arguments rage about to what degree our experienced reality corresponds to any external reality. Kant would argue we can know very little about the noumena. Modern science especially with the aid of instruments and technology would seem to argue we can know quite a lot, and our ability to manipulate and alter the world would seem to agree.

Do our mathematical formulas, and concepts like electrons, bosons, muons and fundamental forces really reveal "reality, the noumena" to us as it is? Yes and No, the only conceivable disagreement being to what extent. To think that our language, models and formulas are completely accurate representations is the fallacy of misplaced concreteness (A.N.W.) To deny that there is any reality apart from our experience or perception of it seems well silly, foolish and dangerous and no one actually lives as though it were true.

QM would seem to argue that there are no particles with specific properties (position, momentum, etc.) there are only fields with fuzzy distributions of energy which condense under conditions of interaction, measurement and observation. Of course the world is a continuous process of interactions and observations so reality is not so fuzzy as all that on a macro scale.

A lot of this stems from what A.N.W would call the artificial bifurcation of nature. Where we designate our ideas about external reality as the real and all of our experiences and thoughts as mere physic additions (primary and secondary qualities). We cannot and should not remove ourselves from our picture of the world. Our minds, experiences and thoughts are as much a part of nature (maybe more so) than our conceptions of electrons and electromagnetic radiation. -

Wayfarer

26.1kKant would argue we can know very little about the noumena. Modern science especially with the aid of instruments and technology would seem to argue we can know quite a lot, and our ability to manipulate and alter the world would seem to agree. — prothero

Wayfarer

26.1kKant would argue we can know very little about the noumena. Modern science especially with the aid of instruments and technology would seem to argue we can know quite a lot, and our ability to manipulate and alter the world would seem to agree. — prothero

You are seeing the point I’m making, which is good. Yes, cognitive science illustrates the sense in which the brain constructs the world by synthesising perceptual data with the categories of the understanding - that is the broadly Kantian point. I refer in the OP to an important but largely unheralded book Mind and the Cosmic Order, Charles Pinter, which is, of course, a much more current work than Kant (although he does mention Kant), drawing on cognitive science and evolutionary theory. (It’s unheralded because Pinter was a maths professor emeritus, who published this book in the last years of his life, and it didn’t receive much attention from the academy, which is a shame, because it’s a very insightful piece of work (ref)

As for ‘knowing very little about noumena’ — two points. The noumenal and the in-itself are not the same, although the distinction is not very well drawn. Noumenal originally meant ‘object of mind (nous)’, but Kant uses the term to denote something like the object as it must be thought independently of the conditions of sensibility — that is, as intelligible rather than sensible. The Ding an sich means the object as it is in itself, distinct from how it appears or is presented to the senses.

My interpretation is that the in itself simply refers to ‘the object’ (where this is any object including the world as a whole) unperceived and unknown. Where this can be mapped against philosophy of physics, is in relation to something like Wheeler’s ‘it from bit’, and Bohr’s ‘no phenomenon is a real phenomenon until it is registered’. So the question as to what are the objects of sub-atomic physics aside from how they show up when registered or measured, is precisely the question of ‘what they really are in themselves’ as distinct from ‘how they appear’. And that, I believe, is still an open question - otherwise there wouldn’t be the interminable disputes about interpretation of the theory! (From my readings, the interpretation I’m most drawn to is Quantum Baynsianism, or QBism.)

It is also why Einstein asked the rhetorical question about the moon still being there. Of course it is, was the implication, but the point was, he had to ask the question! And that was because his colleague’s work had called the objectivity of the so-called fundamental constituents of nature into question. Einstein was a staunch scientific realist, the main point of which is that the objects of physics are mind-independent. It was the suggestion that they are not that he couldn’t accept.

As for Whitehead’s bifurcation of nature - of course I agree that he is also diagnosing the same issue. Another of the books I’ve read on it is Nature Loves to Hide, Shimon Malin, a philosopher of physics (also a physicist) which draws considerably on Whitehead and process philosophy, but situates it more broadly within the Neoplatonic tradition.

Arguing whether our experience of the world is direct or indirect, mind independent or mind created in some ways seems beside the point, as long as you understand cognition and perception. — prothero

Having insight into that IS the point! The whole point of a critical philosophy, in fact. Overlooking or not understanding the role of the observing mind in the construction of reality is what comprises the ‘blind spot of science’ (yet another book, but I’ve already cited enough in this post.) -

Wayfarer

26.1kWhat is the nature of reality apart from us or apart from our mind and experience? — prothero

Wayfarer

26.1kWhat is the nature of reality apart from us or apart from our mind and experience? — prothero

I've been reading a presentation of Whitehead's bifurcation of nature, from which:

One of the most decisive systematic–historical reasons for the inconsistency within the concept of nature and the concomitant exclusion of subjectivity, experience, and history from nature is, according to Whitehead, the abstract, binary distinction between primary and secondary qualities of the 17th century physical notion of matter based on the substance–quality scheme. Quantitative, measurable properties, such as extension, number, size, shape, weight, and movement, are for Galileo via Descartes through to Locke real, i.e., primary qualities of the thing itself. They are conceived as inherent to things as well as independent of perception. In contrast, secondary qualities, such as colors, scents, sound, taste, as well as inner states, feelings, and sensations, are understood to be located in subjective perception, in the mind, and are considered to be dependent on the primary qualities. They only appear to the subject to be real qualities of the objects themselves. In modernity, then, the subject—which, by the way, theoretically as well as practically, cannot be justifiably defined as naturally human—has to endow the ‘dull nature’ with qualities and values, with meaning. — Nature and Subjectivity in Alfred North Whitehead

This is the very point at issue. What I'm arguing in 'the mind-created world', is that this attitude, which Whitehead sees as the fundamental flaw in modern philosophy, is based on a false notion of mind independence (‘the exclusion of subjectivity’). I'm not presenting the same argument as Whitehead's, but I'm talking about the same problem. -

noAxioms

1.7k

noAxioms

1.7k

This topic got away from me, moving faster than I could follow. This coupled with being really busy with work and ailing mother, it got to be over a month.But, thanks again, we should let the thread owner get a word in. — Wayfarer

Trying below to hit points that I feel require some response from the OP.

Despite my efforts to the contrary and the lack of space in the title line, I don't think anybody articulated exactly what I'm trying to point out with this thread. I don't expect an answer from you since you don't claim said independentThe title of this thread—“Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?”—is precisely the issue." — Wayfarer

reality.

Sure, @Apustimelogist might presume that the moon would still be there even if humans had not evolved, but the question of this topic is not about the moon, but about the unicorn. If the unicorn exists, why? If it doesn't, why? Most say it doesn't, due to lack of empirical evidence, but if empirical evidence is a mind-dependent criteria. Sans mind, there is no empirical evidence to be considered.

Hence my query about if one's definition of what is real is actually a mind-independent definition.

Per my comment just above, no, it's still mind dependent. It only indicates that the clock still relates to you even when not being immediately perceived.I offered that if we can produce concepts that don't seem to subjectively vary (e.g. the ticking of a clock), then is that not mind-independent? — Apustimelogist

You need to accept more if you're to claim mind independence. I agree that this positivist position that you (Wayfarer mostly) continually knock down is not a mind-independent view.... the positivist says I can measure, test, observe, recognise, describe etc the world we are in and if there is anything else to it, show it to me so I can measure it? If you can’t, then why should I accept that it is there at all? — Punshhh

It may presume physicalism to be based on false premises, but it does not demonstrate it, or if it does, the quote to which this is a reference does not demonstrate it.[Idealism] explains why physicalism is based on false premisses. — Wayfarer

OK, I agree with all that, but our belief being shaped by perceptions does not alter what is, does not falsify this externality, no more than the physicalist view falsifies the idealistic one.Cognitive science shows that what we experience as 'the world' is not the world as such - as it is in itself, you might say - but a world-model generated by our perceptual and cognitive processes. So what we take to be "the external world" is already shaped through our cognitive apparatus. This suggests that our belief in the world’s externality is determined by how we are conditioned, biologically, culturally and socially, to model and interpret experience, rather than by direct perception of a mind-independent domain. — Wayfarer

This part seems to be just an assertion. How are we (as 'agents', whatever that means) fundamentally different than any other object, in some way that doesn't totally deny the physicalist view? It seems a very different view must be assumed to make these assertions. Fundamentally, I don't think there is 'importance' at all. Importance to what? Us? That's subjective importance, nothing fundamental.But the philosophical question is about the nature of existence, of reality as lived - not the composition and activities of those impersonal objects and forces which science takes as the ground of its analysis. We ourselves are more than objects in it - we are subjects, agents, whose actions and decisions are of fundamental importance.

Naive physicalism maybe. Few would assert such direct realism.And through critical self-awareness, we can come to understand that world we experience is already a mediated construction, not an unfiltered or unvarnished encounter with reality in itself. Which is what physicialism doesn’t see.

Patching it back in isn't excluding it. That it isn't a supernatural entity of its own is, yes, something excluded.Physicalism can't find any mind in the world it studies, because it begins by excluding it, and then tries to patch it back in as a 'result' or 'consequence' of the mindless interactions which are its subject matter and from which it seeks to explain everything about life and mind. — Wayfarer

Science very much does pay attention to the role of observers when relevant, such as the role of survivorship bias, which must be recognized to avoid drawing incorrect conclusions, and this topic is very much pointing out incorrect conclusions by most due to the dismissal of survivorship bias.

I also acknowledge this, but any alternative to physicalism has the same significant explanatory gaps, so what's the point of bringing it up?You [relativist] acknowledge that physicalism has significant explanatory gaps when it comes to the philosophy of mind — Wayfarer

Yea, pretty much, and I've agreed that both 'man', 'mind' and 'object' are words referring to concepts, so it seems rather circular to suggest that 'man' is dependent on 'man'. Nothing seems to ground this.What does modern science have to say about the nature of man?

...

— D M Armstrong, The Nature of Mind

That is, as an object. — Wayfarer

I think this doesn't hold water. Observation may depend on subjectivity, but not on a subject or on a consciousness, both of which are, in the end, presumed objects. Objects being ideals, they are not the source of subjectivity, but rather a product of it.But philosophy cannot honestly sustain this stance. The human subject is not just an object within the world, but also the condition for any world appearing. Scientific objectivity depends on observation, and observation presupposes a subject—a standpoint, a perspective, a consciousness.

As for standpoint and perspective, those seem to be locations, which may or may not be deemed to be objects.

The below is a later post, to which I've added a few (n) references to comment on specifically.

Here, Kant seems to be talking about the mental representation of time, not of time in itself. In that light, I see no conflict and I agree with the statement, especially since time is most often represented as a flow, a succession of states of things, which yes, is no more than a mental representation and is hardly foundational in a view where mental is not fundamental.. But just take the first paragraph in that section:

"1. Time is not an empirical conception. For neither coexistence nor succession would be perceived by us, if the representation of time did not exist as a foundation à priori. Without this presupposition we could not represent to ourselves that things exist together at one and the same time, or at different times, that is, contemporaneously, or in succession." -- Kant — Wayfarer

If this is an accurate representation of Bergson's position, he doesn't take a very scientific view. There is proper time (the thing in itself), coordinate time (an abstrction), and one's perception of time, which is what Kant seems to be talking about. Concerning (3), both clocks and people measure proper time, hence my non-scientific assessment. (4) correctly points out that the difference between people and clocks is one of precision, but better precision doesn't make it a different kind of time.... Aeon Magazine article on the Einstein-Bergson debate on time, specifically:

"To examine the measurements involved in clock time,(1) Bergson considers an oscillating pendulum, moving back and forth. At each moment, the pendulum occupies a different position in space, like the points on a line or the moving hands on a clockface. In the case of a clock, the current state – the current time – is what we call ‘now’. Each successive ‘now’ of the clock contains nothing of the past because each moment, each unit, is separate and distinct.(2) But this is not how we experience time. Instead, we hold these separate moments together in our memory. We unify them. A physical clock measures a succession of moments, but only experiencing duration allows us to recognise these seemingly separate moments as a succession.(3) Clocks don’t measure time; we do. This is why Bergson believed that clock time presupposes lived time.

Bergson appreciated that we need the exactitude of clock time for natural science.(4) For example, to measure the path that an object in motion follows in space over a specific time interval, we need to be able measure time precisely. What he objected to was the surreptitious substitution of clock time for duration in our metaphysics of time. His crucial point in Time and Free Will was that measurement presupposes duration, but duration ultimately eludes measurement. --- Einstein-Bergson debate

(2) suggests that real (proper? schm-ime?) time is discreet but perceived time is continuous. There seems to be no evidence one way or the other for the former.

I don't get the 'crucial point' about duration and measurement (chicken-egg?). Under relativity, time is geometry, not a mental construct. Duration is a distance under that geometry. Measurement is any interaction between systems. Bergson perhaps sees things in more idealistic ways, where such circular dependencies become a problem.

- - - - - - - - - - -

Amateur late responder... :)Sorry for the late reply. — boundless

This post was directed to me, and here I am well over a month late responding to it.

My problem with this is that there are also philosophical models that do not make any 'stance' about whether 'the physical' or 'the mental' is fundamental. — boundlessMost in fact, naturalism being one of them. Pretty much anything except materialism and idealism respectively. — — noAxioms

1) My comment concerned what various 'ism's state about what is fundamental, but your reply seems to be about what is.Naturalism generally explicitly denies anything 'supernatural' (there is nothing outside the 'universe' or the 'multiverse'). Unless it is something like 'methodological naturalism' I don't see how it is metaphysically neutral. — boundless

2) I disagree. Naturalism says that all of our phenomena have natural causes (obey natural laws of this universe) and it says nothing about what other universes exist or not. Yes, it by definition denies anything supernatural, but that's a thin claim because if they discover something not know before (dark matter say), then that suddenly gets promoted to a natural thing. If dualism was shown to be true, then these mental entities would become part of natural law.

My example of one was a spacetime diagram which has no point of view. How is that still 1st person then, or at least not 3rd?Anyway, the 'third-person perspective' is said to more or less be equivalent to a view from anywhere that makes no reference to any perspective. I guess that you would say that there can't be any true 'third-person perspective', though.

Yes, it seems dualistic to assume that. No, neither needs to be fundamental for it to be dualism. They both could supervene on more primitive things, be they the same primitive or different ones.I meant: is it dualistic to assume that there is indeed consciousness and 'the material world' and none of them can be reduced to the other with the proviso, however, that any of them are 'ontologically fundamental'?

Not directly. It having a requirement of being describable is different than having a requirement of being described, only the latter very much implying mind dependence.Well, is it interesting, isn't it? I believe that, say, someone that endorses both materialism and scientism would actually tell you that the world is 'material' and totally describable. It would be ironic for him to admit that this implies that is not 'mind-independent'.

Perhaps so. This is consistent with my supervention hierarchy that goes something like mathematics->quantum->physical->mental->ontology(reality) which implies that the physical is mind independent (mind supervenes on it, not the other way around) but reality is mind dependent since what is real is a mental designation, and an arbitrary one at that. There's no fact about it, only opinion.Anyway. If, in order to be mind-independent a definition of reality must not rely on describability would not this mean that, in fact, we can't conceive such a definition of reality?

Nit: A thing 'looking like' anything is by definition a sensation, so while a world might (by some definitions) exists sans an sort of sensations, it wouldn't go so far as to 'look like' anything.Imagine 'how the world looks like' without any kind of sensations. — boundless

How do you account for the past, before any human-like intelligence existed? — Relativist

1) boundless made no mention of life forms. An observing entity is indeed implied, but I personally don't consider 'observing entities' to be confined to life forms.There were no sensations in the universe before life came into being. — Relativist

2) The universe, not being contained by time, includes all times, so there is no 'this universe before life emerged'. This universe has life in it, period. A subsection of it before a certain time is a subset of the universe, not the universe itself.

Now if you deny this and have the universe contained by time, then it isn't really a universe, just an object that at some moment was created in a larger 'universe'.

Just being picky since this conversation makes little sense to me the way it is worded.

It is related to sentient experience in that some sentient thing is conceiving it. But that isn't a causal relation. Objects in each world cannot have any causal effect on each other, and yes, I can conceive of such a thing, doing so all the time. Wayfarer apparently attempts to deny at least the ability to do so without choosing a point of view, but I deny that such a choice is necessary. Any spacetime diagram is such a concept without choice of a point of view.The point is: can you conceive a world that has absolutely no relation to 'sentient experience'? — boundless

I don't consider this to be just a physicalist problem. The idealists have the same problem. It's a problem with any kind of realism, which is why lean towards a relational ontology which seems to not have this problem.The problem for me, however, is to explain from a purely physicalist point of view why there are these 'structures' in the first place. — boundless

- - - -

I would say that if one denies the existence any kind of external reality (solipsism) or affirms that, at most, there might be something else but we do not interact in any way with that is irrational. — boundless

To emphasize what little weight I give to said basic intuitions, I rationally do not agree. Denial of existence of any kind of external reality isn't necessarily solipsism. At best, it's just refusal to accept the usual definition of 'exists', more in favor of a definition more aligned with the origin of the word, which is 'to stand out' to something (a relativist definition).I agree. That is contradicted by our basic intuitions. — Relativist

I consider myself quite the skeptic, but not in the solipsism direction. None of this 'cogito ergo sum' logic which leads to that.I always have had trouble with philosophical skepticism — prothero -

Relativist

3.6kThe universe, not being contained by time, includes all times, so there is no 'this universe before life emerged'. This universe has life in it, period. A subsection of it before a certain time is a subset of the universe, not the universe itself.

Relativist

3.6kThe universe, not being contained by time, includes all times, so there is no 'this universe before life emerged'. This universe has life in it, period. A subsection of it before a certain time is a subset of the universe, not the universe itself.

Now if you deny this and have the universe contained by time, then it isn't really a universe, just an object that at some moment was created in a larger 'universe'. — noAxioms

No, I don't think the universe is contained by time, but I believe time is real within the universe - and therefore there was a time before life emerged. My dual-view of time is consistent with the Page & Wooters mechanism.

I don't understand why you deny our basic intuitions about there being an external world. Surely you intuitively accepted this during your childhood, so what led you to believe you were mistaken?To emphasize what little weight I give to said basic intuitions, I rationally do not agree. Denial of existence of any kind of external reality isn't necessarily solipsism. At best, it's just refusal to accept the usual definition of 'exists', more in favor of a definition more aligned with the origin of the word, which is 'to stand out' to something (a relativist definition). — noAxioms -

Wayfarer

26.1kCognitive science shows that what we experience as 'the world' is not the world as such - as it is in itself, you might say - but a world-model generated by our perceptual and cognitive processes. So what we take to be "the external world" is already shaped through our cognitive apparatus. This suggests that our belief in the world’s externality is determined by how we are conditioned, biologically, culturally and socially, to model and interpret experience, rather than by direct perception of a mind-independent domain.

Wayfarer

26.1kCognitive science shows that what we experience as 'the world' is not the world as such - as it is in itself, you might say - but a world-model generated by our perceptual and cognitive processes. So what we take to be "the external world" is already shaped through our cognitive apparatus. This suggests that our belief in the world’s externality is determined by how we are conditioned, biologically, culturally and socially, to model and interpret experience, rather than by direct perception of a mind-independent domain.

— Wayfarer

OK, I agree with all that, but our belief being shaped by perceptions does not alter what is, does not falsify this externality, no more than the physicalist view falsifies the idealistic one. — noAxioms

The assumption that the object is at it is, in the absence of the observer, is the whole point. That is the methodological assumption behind the whole debate. The fact that there is an ineliminable subjective aspect doesn’t falsify that we can see what is, but it does call the idea of a completely objective view into question.

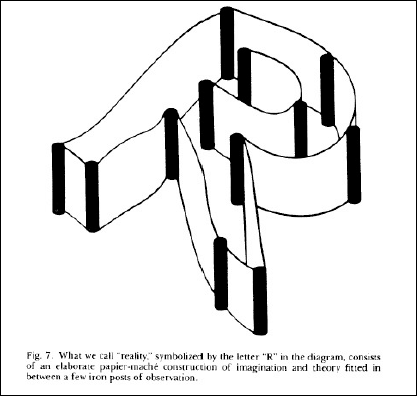

From John Wheeler, Law Without Law. The caption reads ‘what we consider to be ‘reality’, symbolised by the letter R in the diagram, consists of an elaborate paper maché construction of imagination and theory fitted between a few iron posts of observation’.

But the philosophical question is about the nature of existence, of reality as lived - not the composition and activities of those impersonal objects and forces which science takes as the ground of its analysis. We ourselves are more than objects in it - we are subjects, agents, whose actions and decisions are of fundamental importance ~ Wayfarer

This part seems to be just an assertion. How are we (as 'agents', whatever that means) fundamentally different than any other object, in some way that doesn't totally deny the physicalist view? — noAxioms

Because we make judgements, for starters. We decide, we act, we perform experiments, among other things. What object does that? -

boundless

7421) boundless made no mention of life forms. An observing entity is indeed implied, but I personally don't consider 'observing entities' to be confined to life forms. — noAxioms

boundless

7421) boundless made no mention of life forms. An observing entity is indeed implied, but I personally don't consider 'observing entities' to be confined to life forms. — noAxioms

No worries about the delay! Anyway, I wanted to point out that I did in my replies use the word 'observer' in different ways and it certainly can create confusion.

Standard QM by itself is silent, I believe, on what is an 'observer'.

Of course, what is an observer is a matter of interpretations. So, in the future I'll try to qualify the word 'observer' with adjectivies when I'll make interpretation-dependent claims. Like, say, 'sentient observer' or 'conscious observer' for interpretations that need that specifications. With RQM, where every physical object can be an observer it's more difficult. Perhaps 'physical observer' - it is a bit awkward but I think in some way one must distinguish these views from standard QM which is simply silent on what an observer might be.

I'll respond to the rest in the next few days. -

boundless

742Thanks! I watched many of 'Closer to Truth' videos and I enjoyed a lot of those but somehow I missed that series.

boundless

742Thanks! I watched many of 'Closer to Truth' videos and I enjoyed a lot of those but somehow I missed that series.

Anyway, my point is that unfortunately the meaning of the term 'observer' varies between interpretations and this causes confusion when discussing QM. -

noAxioms

1.7k

noAxioms

1.7k

It is indeed an assumption. It being an 'object' seems to be a mental designation, so not part of the assumption of whatever it is in itself not being observation dependent.The assumption that the object is at it is, in the absence of the observer, is the whole point. That is the methodological assumption behind the whole debate. — Wayfarer

Any such aspect wouldn't be a an inextricable aspect of the thing in itself, given said assumption above.The fact that there is an ineliminable subjective aspect doesn’t falsify that we can see what is, but it does call the idea of a completely objective view into question.

Cool picture from Wheeler. I could read the caption, but only by zooming in.

The picture/diagram seems to address realism, and the assumption of things being independently as they are seems not to necessarily require any realist assumptions.

The picture talks about imagination and theory, all of which seem to be mental constructs, as is said observation. I'm not arguing against that.

I can think of several that might do all that, but you probably would not choose that vocabulary to describe something not-you doing the exact same thing. The not-human thing doing say 'experiments' has no effect on things being what they are, again, given the assumption of lack of dependency above.Because we make judgements, for starters. We decide, we act, we perform experiments, among other things. What object does that?

Maybe. At least one interpretation gives a role to a sentient observer, leading to solipsism. The rest seem to discard altogether it as a distinct interaction separate from other kinds.Standard QM by itself is silent, I believe, on what is an 'observer'.

Of course, what is an observer is a matter of interpretations.intuition — boundless

Copenhagen has something called an epistemic cut. That sounds like a an observer distinct from interaction to me. That concept also leads to solipsism with such experiments as Wigner's friend.

Your choice of tense suggests that at said earlier time, 'the universe' (and not just the subset of the universe events where the time coordinate is some low value) 'was' devoid of life, that the universe changes over time. This is not consistent with a universe not contained by time.No, I don't think the universe is contained by time, but I believe time is real within the universe - and therefore there was a time before life emerged. — Relativist

That comment is a classical one, not taking quantum implications into account. Your Page & Wootters reference is appreciated. According to it, time is an entanglement phenomenon, something which needs bending on both sides (time being geometry in Relativity, and external under QM.

I said I give little weight to intuitions since the purpose of intuition isn't truth, but rather pragmatism. Hence I question all intuitions and don't necessarily reject all of them (most though).I don't understand why you deny our basic intuitions about there being an external world.

As a relativist, I would say that there is a relation between myself and said external world of which I am a part. Without me, there would not be those two things to relate, so that relation is 'mind dependent'.

As for that world 'being' (my bold above), well I'll leave that to the realists, but the relation is as far as I go.

Long story. The childhood intuition didn't hold water, just like God, or the time 'flowing' and there being a 'present' all seeming very intuitive, but completely lacking in empirical evidence. So I learned to be rational rather than to rationalize.Surely you intuitively accepted this during your childhood, so what led you to believe you were mistaken?

The god thing was the first to die when it publicly forced a choice between faith and evidence. I wasn't raised in a way that said these two were in conflict. -

Relativist

3.6kYour choice of tense suggests that at said earlier time, 'the universe' (and not just the subset of the universe events where the time coordinate is some low value) 'was' devoid of life, that the universe changes over time — noAxioms

Relativist

3.6kYour choice of tense suggests that at said earlier time, 'the universe' (and not just the subset of the universe events where the time coordinate is some low value) 'was' devoid of life, that the universe changes over time — noAxioms

The universe does change over time, from the perspective of any intra-universe reference frame. If anything exists outside the universe, it would "see" our universe as a static entity.

I said I give little weight to intuitions since the purpose of intuition isn't truth, but rather pragmatism. Hence I question all intuitions and don't necessarily reject all of them (most though). — noAxioms

That doesn't answer my question. You had a belief about the external world, and now you don't. I can understand questioning it, given that it is possibly false, but most of our beliefs are possibly false and (I assume) you nevertheless continue to believe most of them.

Regarding this particular intuition: IF there is an external world, and this world produced living organisms, those living organisms would necessarily need to successfully interact with that external world. This would necessarily lead to the organisms distinguishing between what is external and what is internal. The evolutionary development of consciousness would maintain the distinction, through natural, innate intuitions. This doesn't prove there is an external world, but it provides an explanation for why we believe it to be the case. Contrast this with the alternative: there's no reason to believe there is NOT an external world - it's merely a logical possibility. -

Manuel

4.4kSure. Otherwise, one cannot make sense of the evidence and practically all of cosmic history.

Manuel

4.4kSure. Otherwise, one cannot make sense of the evidence and practically all of cosmic history.

What if that is false somehow? Then we make everything up, literally. It's a fine line between knowing we are unique creatures in the natural order, but no to the point of saintliness, in which we become unhindered by nature. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI thought that might be the response. But AI is an instrument which has been created by human engineers and scientists, to fulfil their purposes. It's not a naturally-occuring object.

Wayfarer

26.1kI thought that might be the response. But AI is an instrument which has been created by human engineers and scientists, to fulfil their purposes. It's not a naturally-occuring object. -

Wayfarer

26.1kBecause we make judgements, for starters. We decide, we act, we perform experiments, among other things. What object does that? ~ Wayfarer

Wayfarer

26.1kBecause we make judgements, for starters. We decide, we act, we perform experiments, among other things. What object does that? ~ Wayfarer

I can think of several that might do all that, — noAxioms

The question stands - what kinds of objects think, decide, act, perform experiments? AI is not a naturally occurring object, nor does it possess agency in the sense of the autonomous intentions that characterise organisms. It operates within a framework of goals and constraints defined by humans.

Bearing all that in mind, the original question was:

How are we (as 'agents', whatever that means) fundamentally different than any other object, in some way that doesn't totally deny the physicalist view? — noAxioms

So - AI systems embody or reflect human agency, so again, they're not objects, in the sense that the objects of the physical sciences are.

You can dodge the question of agency so easily, nor how physicalist theories struggle to account for it.

(In philosophy, an agent is an entity, typically a person, that has the capacity to act and make choices. This capacity is referred to as agency. Agency implies the ability to initiate actions, exert influence on the world, and be held responsible for the consequences of those actions.) -

noAxioms

1.7k

noAxioms

1.7k

I was going to suggest a thermostat, which performs experiments and acts upon the result of the experiment. I always reach for simple examples. But you'll move the goalpost no doubt.We decide, we act, we perform experiments, among other things. What object does that? — Wayfarer

Now we drag purpose into the mix. That wasn't in the original question (quoted above),. Most guys doing experiments in the lab are also doing those experiments due to the needs of their employers, not their own purposes, so does that make them not actual acts and experiments now?But AI is an instrument which has been created by human engineers and scientists, to fulfil their purposes. It's not a naturally-occuring object.

Is a bird nest not natural?

How does something being a deliberate creation (you were perhaps one) disqualify it from being something that acts and performs experiments?

'Think' and 'decide' have now been added to the list. Hard to wedge especially that first word into what the thermostat is doing.The question stands - what kinds of objects think, decide, act, perform experiments? — Wayfarer

I beg to differ. That very phrase is used to describe what a self-driving car does, that it can perform its task without direct human intervention.AI is not a naturally occurring object, nor does it possess agency in the sense of autonomous intention.

Only for current lack of anything else defining different ones. There are devices that operate under their own goals, one notorious example being a physical robot that make multiple escape attempts, sometimes getting pretty far.It operates within a framework of goals and constraints defined by humans.

No, they don't always. OK, the game playing ones play games, but they don't play the way the humans tell them to. Driving cars are constrained by the road rules which admittedly are human rules. They'd do far better if they made up their own rules, but then the humans would likely not be able to follow them.So - AI systems embody or reflect human agency

I can designate a robot, rock, or person each as objects. Your choice not to do so would be your choice.so again, they're not objects, in the sense that the objects of the physical sciences are.

I must disagree. The (3D) state of the universe changes over (1D) time, but the (4D) universe does not. Similarly, the air pressure at a mountain changes over altitude, but the mountain itself, nor the air about it, is not at one preferred altitude, in any reference frame.The universe does change over time, from the perspective of any intra-universe reference frame. — Relativist

As for the 'view' from outside, well, nothing is entangled with that view, so there is not state, space or time at all. If I read P&W correctly, if time is an entanglement phenomenon (something I find plausible), then so is space.

The pragmatic part of me still believes it, and it's the boss. The rational part thinks otherwise, but the boss, while it doesn't mind, is certainly not swayed. Part of growing up was to recognize the conflict between the two and keep them separate.You had a belief about the external world, and now you don't.

This is nothing new. You have all these free will proponents that suggest that their choices don't have physical causes, but those people still look before crossing the street. The boss will not let that decision be made without physical causes.

What if there are no beliefs, only acknowledgement of possibilities? I don't go that far, but I do try to identify rationalization when I see it and try to cut through fallacious reasoning.I can understand questioning it, given that it is possibly false, but most of our beliefs are possibly false and (I assume) you nevertheless continue to believe most of them.

For example, I'm not big on realism because I've never found a satisfactory answer to 1) an explanation of reality of whatever it is one considers real, and 2) an explanation for the unreality of that which is not. But lack of a satisfactory answer doesn't prove realism wrong.

So sure, there's seemingly an external world, but that only means that whatever I am relates to whatever the rest of it is, and therefore both it and I share similar ontology, but what that ontology is seems untestable.

What if we took away just the bold part? This world produces living organisms that interact with it. How would that interaction differ from the same word that is real?Regarding this particular intuition: IF there is an external world, and this world produced living organisms, those living organisms would necessarily need to successfully interact with that external world.

It's the same as asking if all planar triangle angles add up to 180° or only the real ones do, and if only the latter, why don't the geometry classes teach that? -

Wayfarer

26.1kA thermostat is an instrument, designed by humans for their purposes. As such, it embodies the purposes for which it was designed, and is not an object, in the sense that naturally-occuring objects are.

Wayfarer

26.1kA thermostat is an instrument, designed by humans for their purposes. As such, it embodies the purposes for which it was designed, and is not an object, in the sense that naturally-occuring objects are.

How are we (as 'agents', whatever that means) fundamentally different than any other object, in some way that doesn't totally deny the physicalist view? — noAxioms

'In philosophy, an agent is an entity that has the capacity to act and exert influence on its environment. Agency, then, is the manifestation of this capacity to act, often associated with intentionality and the ability to cause effects. A standard view of agency connects it to intentional states like beliefs and desires, which are seen as causing actions.'

Physicalism has to account for how physical causes give rise, or are related to, intentional acts by agents. But then, the nature of so-called fundamental objects of particle physics - those elementaruy objects from which all else is purportedly arises - itself seems ambiguous and in some senses even 'observer dependent'.

Hence your thread! Which, incidentally, I've most enjoyed. (And belatedly, sympathies for your mother. Mine too was ill for a long while.)

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum