-

Wayfarer

26.2kI’m distinguishing between two levels — both valid, but different in scope. On the empirical level, of course we say the cosmos existed long before us. But from the standpoint of critical philosophy, what we mean by “cosmos,” “existence,” or “visibility” only makes sense within the framework of our cognitive faculties. This is not a denial of reality, but a reflection on the conditions under which such claims are intelligible.

Wayfarer

26.2kI’m distinguishing between two levels — both valid, but different in scope. On the empirical level, of course we say the cosmos existed long before us. But from the standpoint of critical philosophy, what we mean by “cosmos,” “existence,” or “visibility” only makes sense within the framework of our cognitive faculties. This is not a denial of reality, but a reflection on the conditions under which such claims are intelligible.

One of the key functions of transcendental critique is to resist the tendency to absolutize appearances (which is what becomes 'scientism'.) Scientific knowledge gives us real and powerful insights into nature — but those insights are always shaped by judgement, concept, and perspective. When we forget this, we turn empirical knowledge into a kind of metaphysical absolute: what begins as methodological naturalism silently morphs into metaphysical naturalism, the belief that only science can show us what is.

The OP is not metaphysics in the dogmatic or speculative sense. What I’m doing — in line with Kantian principles — is laying bare the assumptions that science itself rests on. What does it mean for something to be “observable”? What is the status of space and time? These aren’t speculative metaphysical questions — they are conditions of possibility for scientific knowledge itself. Ignore them, and you don’t avoid metaphysics — you fall into it unwittingly. 'No metaphysics' ends up becoming a particularly poor metaphysics. -

Gnomon

4.4k

Gnomon

4.4k

I think your Epistemological approach is more appropriate for a philosophy forum, than the Empirical methods that some advocate. Besides, the Uncertainty Principle of Quantum Physics seemed to open the door to Epistemological discussions. But injecting Philosophy into Physics often raises objections of Mysticism and Woo-woo. So, we typically avoid using the fraught term "spiritual" when referring to Mental, as opposed to Material, essences & causes. Does Phenomenology successfully bridge over the spooky abyss of Spiritualism? :smile:The approach in the Mind Created World is epistemological rather than ontological - about the nature of knowing rather than about what the world is made from or of. I said 'The constitution of material objects is a matter for scientific disciplines (although I’m well aware that the ultimate nature of these constituents remains an open question in theoretical physics).' Also notice the word 'spiritual' does not appear in it. — Wayfarer -

Wayfarer

26.2kDoes Phenomenology successfully bridge over the spooky abyss of Spiritualism? — Gnomon

Wayfarer

26.2kDoes Phenomenology successfully bridge over the spooky abyss of Spiritualism? — Gnomon

Husserl was never overtly 'spiritual' (whatever that means) but some say his emphasis on the transcendental aspects of phenomenology became somewhat too idealist later in life. Many of his successors, specifically Heidegger (with whom he had a somewhat fraught relationship) were much less sympathetic to that dimension of Husserl's thought, and more concerned with being-in-the-world.

One of the online articles I've found informative is The Phenomenological Reduction (IEP). -

Janus

18kAn unfortunate deductive error inferring from our inability to say with certainty what kind of existence unperceived objects have to a conclusion that there could be no such actual existence, and that saying there is any such existence is incoherent. It's called 'confusing oneself with a truism'; the truism being that it is only minds that can know anything. What is more remarkable is that this confusion is obstinately repeated ad nauseum, making me wonder what the point or motivation for such idiocy could be.

Janus

18kAn unfortunate deductive error inferring from our inability to say with certainty what kind of existence unperceived objects have to a conclusion that there could be no such actual existence, and that saying there is any such existence is incoherent. It's called 'confusing oneself with a truism'; the truism being that it is only minds that can know anything. What is more remarkable is that this confusion is obstinately repeated ad nauseum, making me wonder what the point or motivation for such idiocy could be. -

Janus

18kThe urge to devour and assimilate what is not oneself. — Jamal

Janus

18kThe urge to devour and assimilate what is not oneself. — Jamal

That's an interesting take. Instead of oneself being a small part of the Universe, the Universe must instead be seen as being a small part of oneself.

It must also be a need to have everyone agree with oneself, given that the rejoinder to any disagreement is always predictably "if you don't agree then you must not have understood" coupled with some attempt to cast aspersions on the others' level of education. It's a sorry spectacle...

Don't feel bad. — Jamal

No, he really ought to feel bad. -

Wayfarer

26.2kif you don't agree then you must not have understood" — Janus

Wayfarer

26.2kif you don't agree then you must not have understood" — Janus

But you clearly don't understand. Your arguments don't display a proper grasp of the issues. I've tried for years to explain ideas to you, to be met first with incomprehension, then with invective, and then with insults. So I generally ignore your remarks, a practice I will now resume. -

Janus

18kYour capacity for self-delusion is truly remarkable. "Proper grasp" of course means 'understood as Wayfarer the enlightened one does". You apparently have no capacity to understand other perspectives or to deal intelligently with critiques of your stipulative nonsense.

Janus

18kYour capacity for self-delusion is truly remarkable. "Proper grasp" of course means 'understood as Wayfarer the enlightened one does". You apparently have no capacity to understand other perspectives or to deal intelligently with critiques of your stipulative nonsense. -

Banno

30.6kThe urge to devour and assimilate what is not oneself. — Jamal

Banno

30.6kThe urge to devour and assimilate what is not oneself. — Jamal

Jack adopted this form of life. To be fair, when a kitten he was hit by a car or bike and lost for a few weeks, only to be found emaciated and wounded. He was eating the maggots on his legs.

After that he ate everything.

Returning to his goatish essence. -

Tom Storm

10.9kThat's an interesting take. Instead of oneself being a small part of the Universe, the Universe must instead be seen as being a small part of oneself. — Janus

Tom Storm

10.9kThat's an interesting take. Instead of oneself being a small part of the Universe, the Universe must instead be seen as being a small part of oneself. — Janus

This reminds me there's an ongoing discussion on woke that’s been a curious read, but it’s easy to forget how much the concept operates across all fields and orientations; as orthodoxy, as sets of axiomatic principles, often justified by universalising principles like equality, solidarity or reason, and sometimes by something closer to faith.

I'm not including you in this, although sometimes you do seem a little dogmatic for my taste. But then I'm reminded that you have a strong countercultural leaning, which I dig.

I think there’s room on this site for a different kind of discussion, where perhaps a third person helps facilitate a conversation between two members who don’t agree and seem to be talking past each other. I often wonder, with you and @Janus (and I probably align a bit more with him), whether a productive shift could happen with the right kind of facilitation.

What I think I see is that conversations on the forum often get stuck around 1) the justification of axioms, 2) accusations of misunderstanding or bad faith, 3) acrimony. It’s as if we’re hard-wired for conflict over difference. The worst offenders seem to call others liars and sophists when they are challenged by difference.

My interest on this site is probably trying to understand positions I don’t necessarily agree with, it's hard to do because one often ends up trying to defend one's own views on something along the way. The price we often pay for conversation. -

Wayfarer

26.2kNot all the exchanges in this thread have been acrimonious, in fact they're the minority. Ludwig and I have managed to negotiate a pretty detailed conversation without it departing from civility, likewise for many other contributors. I'm not inclined to bend over backwards to posters who frequently engage in ad hominems and who are obviously antagonistic.

Wayfarer

26.2kNot all the exchanges in this thread have been acrimonious, in fact they're the minority. Ludwig and I have managed to negotiate a pretty detailed conversation without it departing from civility, likewise for many other contributors. I'm not inclined to bend over backwards to posters who frequently engage in ad hominems and who are obviously antagonistic.

As far as being dogmatic is concerned, please be so kind as to indicate where you think this shows up in the OP. -

Wayfarer

26.2kI've reflected recently on how much I've learned on this forum - even from you! I'd never heard of Davidson or Austin or the other anglo analyticals before. Likewise Apokrisis and biosemiotics - I've read a lot about that now. Joshs has taught be a lot about phenomenology. This comes mainly from following up what they and others have said. It also comes from disagreements - when others disagree with your contributions, it can be a great learning opportunity, provided they're grounded in a genuine understanding.

Wayfarer

26.2kI've reflected recently on how much I've learned on this forum - even from you! I'd never heard of Davidson or Austin or the other anglo analyticals before. Likewise Apokrisis and biosemiotics - I've read a lot about that now. Joshs has taught be a lot about phenomenology. This comes mainly from following up what they and others have said. It also comes from disagreements - when others disagree with your contributions, it can be a great learning opportunity, provided they're grounded in a genuine understanding.

Of course not every thread and every contributor is an opportunity for learning, but overall and for a public forum, I think thephilosophyforum.com has a good reputation. -

Janus

18kWhat I think I see is that conversations on the forum often get stuck around 1) the justification of axioms, 2) accusations of misunderstanding or bad faith, 3) acrimony. It’s as if we’re hard-wired for conflict over difference. The worst offenders seem to call others liars and sophists when they are challenged by difference. — Tom Storm

Janus

18kWhat I think I see is that conversations on the forum often get stuck around 1) the justification of axioms, 2) accusations of misunderstanding or bad faith, 3) acrimony. It’s as if we’re hard-wired for conflict over difference. The worst offenders seem to call others liars and sophists when they are challenged by difference. — Tom Storm

These are good points Tom. I think people often forget that what they are presenting is merely one perspective. If they react defensively it seems to indicate that they have so much invested in their particular hobbyhorse that critique feels threatening. Hence the accusations of misunderstanding and lack of education.

The irony with the situation between Wayfarer and myself is that I am very familiar with all the arguments he presents, I used to present such arguments myself (and he knows this but does not want to admit it), but I have come to think there is very good reason to question the soundness of the presumptions upon which those arguments are based. He seems to take my critiques as personal attacks, when all I'm doing is expressing genuine objections. -

Tom Storm

10.9kNot all the exchanges in this thread have been acrimonious, in fact they're the minority. — Wayfarer

Tom Storm

10.9kNot all the exchanges in this thread have been acrimonious, in fact they're the minority. — Wayfarer

Never said they were. I'm pointing to something I've noticed about the ones that are.

As far as being dogmatic is concerned, please be so kind as to indicate where you think this shows up in the OP. — Wayfarer

I'm not going to spend valuable time seeking out examples. And I said "a little", besides, I'm not saying it's your modus operandi. It's just my take on the way you sometimes talk, for instance, about Dennett, physicalism, and people who don't buy into idealism. You seem to put them down, almost Bentley Hart style. It's clear you believe idealism is true and that materialism is demonstrably false. Having said that, I greatly value your contributions and read almost everything you post as I consider you the most clear and scrupulous proponent of idealism and higher consciousness studies here. -

Tom Storm

10.9kThese are good points Tom. I think people often forget that what they are presenting is merely one perspective. If they react defensively it seems to indicate that they have so much invested in their particular hobbyhorse that critique feels threatening. Hence the accusations of misunderstanding and lack of education. — Janus

Tom Storm

10.9kThese are good points Tom. I think people often forget that what they are presenting is merely one perspective. If they react defensively it seems to indicate that they have so much invested in their particular hobbyhorse that critique feels threatening. Hence the accusations of misunderstanding and lack of education. — Janus

Yes, it often happens amongst members here. Sometimes watching is like a slow motion car crash. -

Jamal

11.8k

Jamal

11.8k

There's no doubt in my mind that @Wayfarer is driven fundamentally by an agenda, but I'm in two minds about whether that's a bad thing. On the one hand, it leads one to avoid proper engagement with any philosophy that cannot be weaponized; on the other hand, a completely neutral approach to philosophy is really boring. -

Tom Storm

10.9kMy intention was not to have a go at whose contributions I value. I apologise if that's how it was heard. There are several members who are rather ardently flogging a worldview, which I don't mind as long as it is made clear and conducted with good grace, particularly when it is disagreed with. This site is a lovely, gentle way to engage with ideas and approaches one might not initially be drawn to. Having a personality bring it to life via conversation is wonderful, despite all the inherent deficiencies this may also bring.

Tom Storm

10.9kMy intention was not to have a go at whose contributions I value. I apologise if that's how it was heard. There are several members who are rather ardently flogging a worldview, which I don't mind as long as it is made clear and conducted with good grace, particularly when it is disagreed with. This site is a lovely, gentle way to engage with ideas and approaches one might not initially be drawn to. Having a personality bring it to life via conversation is wonderful, despite all the inherent deficiencies this may also bring. -

Wayfarer

26.2kThe irony with the situation between Wayfarer and myself is that I am very familiar with all the arguments he presents, — Janus

Wayfarer

26.2kThe irony with the situation between Wayfarer and myself is that I am very familiar with all the arguments he presents, — Janus

Well, I want to get this straight. You've heard them many times, but I say you don't understand them. Take this latest exchange - it began with:

we know that the cosmos was visible prior to the advent of percipients, otherwise there never would have been any percipients. — Janus

This is a misrepresentation. The reason you say this is 'repetitive' is because you (and many others) misrepresent what is being said over and over again, to which I try and respond. In this case, I copied a couple of paragraphs from the original post, and then added commentary to the effect that it is not being argued that there was no universe prior to observers. So we get to:

An unfortunate deductive error inferring from our inability to say with certainty what kind of existence unperceived objects have to a conclusion that there could be no such actual existence, and that saying there is any such existence is incoherent. It's called 'confusing oneself with a truism'; the truism being that it is only minds that can know anything. — Janus

I say: “We can't say what existence means apart from mind.”

And you interpret as:

“Nothing existed before minds.”

The question I’m raising is not whether the universe existed, but what it means to say so. That is: what conditions make such a claim intelligible at all? When you say “the cosmos was visible prior to the advent of percipients,” you're smuggling in a category — visibility — that only has meaning within the context of experience. That’s the point I keep returning to.

You dismiss this as a “confusion with a truism” — that “only minds can know.” But this isn't about knowledge in the empirical or factual sense. It's about the conditions for meaningful discourse — the structure that allows us to form concepts like “universe,” “visibility,” or “existence” in the first place. I’m not making a deductive claim about what did or didn’t exist. I’m making a transcendental claim about what makes it possible to talk about existence at all.

To be clear: I’m not arguing that the universe didn’t exist before percipients. I’m arguing that the very concept of the universe — including any claims about its being — is bound to the framework of cognition. That’s not speculative metaphysics. It’s critical philosophy — and it was precisely this confusion that Kant sought to untangle.

The “actual existence” which you say must have pre-existed observers is exactly what’s at issue. I’m not denying the reality of the universe prior to observation — I’m saying that what it is, apart from any possible mode of perception, conception, or representation, is not something that science can tell us, because science already presupposes intelligibility, structure, and observation. That is Kant's 'in itself' - to which I add, it neither exists nor doesn't exist. Nothing can be said about it.

Of course we can reconstruct the early universe. I’m not contesting any of that. But all such reconstructions take place within the space of reason and inference — they’re appearances, structured by theory, observation, and mathematical representation. That’s not a flaw — it’s the condition of knowledge. But it does mean that the thing-in-itself — the “actual existence” prior to appearance — remains transcendent with respect to what science can access.

That’s the critical point: science gives us knowledge of appearances, not of reality unconditioned by perspective. When we forget this distinction, we turn methodological naturalism into a metaphysical doctrine — and mistake the limits of our mode of knowing for the limits of what is.

So — this is not “an unfortunate deductive error.” It’s a position foundational to a great deal of contemporary philosophy, especially in European traditions, though less so in the Anglo-American analytic stream.

There’s an online journal, Constructivist Foundations, which is an international, peer-reviewed e-journal dedicated to the study of constructivist and enactive approaches across philosophy, cognitive science, second-order cybernetics, neurophenomenology, and non-dualizing thought. I don’t have the academic credentials to make the cut in a journal of that kind, but I’d suggest that the core argument of Mind-Created World would be regarded as fairly stock-in-trade in that context — not a mistake, but a well-recognized philosophical position.

So I'd appreciate it if you might acknowledge that I'm not 'repeating the same mistake ad nauseum', as I don't think I am.

I don't have an agenda - I have an interest in recovering what I think is the meaning of philosophy proper, which is not at all obvious, and very difficult to discern. I say that philosophical and scientific materialism is parasitic upon philosophy proper. But the times, they are a'changin. -

Tom Storm

10.9kTo be clear: I’m not arguing that the universe didn’t exist before percipients. I’m arguing that the very concept of the universe — including any claims about its being — is bound to the framework of cognition. That’s not speculative metaphysics. It’s critical philosophy — and it was precisely this confusion that Kant sought to untangle. — Wayfarer

Tom Storm

10.9kTo be clear: I’m not arguing that the universe didn’t exist before percipients. I’m arguing that the very concept of the universe — including any claims about its being — is bound to the framework of cognition. That’s not speculative metaphysics. It’s critical philosophy — and it was precisely this confusion that Kant sought to untangle. — Wayfarer

Well yes, and it's part of postmodernism too. Our frameworks, and reality are a contingent product.

I don't have an agenda - I have an interest in recovering what I think is the meaning of philosophy proper, which is not at all obvious, and very difficult to discern. I say that philosophical and scientific materialism is parasitic upon philosophy proper. — Wayfarer

How woudl you say this isn't an agenda, or at the very least a project? -

Wayfarer

26.2kSure it's a project. I enrolled late at University in the second half of my twenties, and ended up doing a BA and MA hons in philosophy and related subjects. I have nothing external to show for it, never managed to make anything much from it, but I'm still pursuing it.

Wayfarer

26.2kSure it's a project. I enrolled late at University in the second half of my twenties, and ended up doing a BA and MA hons in philosophy and related subjects. I have nothing external to show for it, never managed to make anything much from it, but I'm still pursuing it. -

Janus

18kI copied a couple of paragraphs from the original post, and then added commentary to the effect that it is not being argued that there was no universe prior to observers. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kI copied a couple of paragraphs from the original post, and then added commentary to the effect that it is not being argued that there was no universe prior to observers. — Wayfarer

So, you agree there was a universe prior to observers. What then are we disagreeing about?

The question I’m raising is not whether the universe existed, but what it means to say so. — Wayfarer

It's obvious what it means to say there was a universe prior to observers...it means, if true, that there was a universe prior to observers.

When you say “the cosmos was visible prior to the advent of percipients,” you're smuggling in a category — visibility — that only has meaning within the context of experience. That’s the point I keep returning to. — Wayfarer

It's a lame point though, and nothing is being "smuggled in" because it is simply a truism that everything we say only has meaning within the context of human experience and the judgements we make on the basis of experience. Since it obviously applies to everything there is no point bringing it up. As to visibility, we know what it means for something to be visible, and the idea doesn't depend on it being seen. Similarly we know what it means for something to exist, and it doesn't depend on the existence of humans.

It's about the conditions for meaningful discourse — the structure that allows us to form concepts like “universe,” “visibility,” or “existence” in the first place. I’m not making a deductive claim about what did or didn’t exist. I’m making a transcendental claim about what makes it possible to talk about existence at all. — Wayfarer

The fact that we exist and possess language makes it possible to talk about existence and anything else. As to "meaningful discourse", what makes sense to each of us may differ depending on our preconceptions and assumptions. You speak as though there is a fact of the matter regarding what it could be meaningful to say, but that is simply not true.

You are entitled to say that the idea of existence independent of human experience makes no sense to you, but you cannot justifiably pontificate about what should or should not make sense to others. It is that kind of dogmatic assumption that leads you to think that anyone who disagrees with your stipulations must not understand.

When we forget this distinction, we turn methodological naturalism into a metaphysical doctrine — and mistake the limits of our mode of knowing for the limits of what is. — Wayfarer

The irony is it seems that it is you that wants to restrict "what is" to what humans can know. I allow that all the things we experience have their own existence and had their own existence before there were any humans.

I don’t have the academic credentials to make the cut in a journal of that kind, but I’d suggest that the core argument of Mind-Created World would be regarded as fairly stock-in-trade in that context — not a mistake, but a well-recognized philosophical position. — Wayfarer

Perhaps...I tend to doubt that, but in any case so what?...that there are others who might think as you do doesn't mean much. There are others who think all kinds of things, and the majority of intelligent well-educated people seem to be metaphysical realists. I'm not going to find appeals to authority convincing.

the meaning of philosophy proper, — Wayfarer

The very idea of "philosophy proper" is dogmatic. There is no fact of the matter...it cannot be anything more than your opinion.

. -

Ludwig V

2.5k

Ludwig V

2.5k

A neat point. I'm not sure how convincing it would be for a true idealist. I think you might find that they might argue that since the cosmos was not seen (and could not be seen) before percipients appeared, there is no proof that it was visible. We won't be impressed, of course.Right, so we know that the cosmos was visible prior to the advent of percipients, otherwise there never would have been any percipients. — Janus

Oh, I don't mean to suggest that seeing is not more complicated than it might seem. One difficulty is that the borderline between seeing and understanding is, let me say, a bit moot. Arguable, you will have some description for what you see, which implies some level of understanding. If I see a smudge on the horizon on Monday, and it turns out on Tuesday, when the ship arrives in port that it is a Russian oil tanker, did I see the tanker on Monday, (but did not see that it was a Russian oil tanker) or did I see a smudge on Monday, which turned out to be a Russian oil tanker on Tuesday. I think seeing is achieved on contact, so to speak, whereas understanding is never complete.I'd say there is always more to be seen in the seeing of anything, more and finer detail and also different ways of seeing as per the different ways, for example, different species see things. — Janus

That sets a simple context. Different ways of seeing are another complication. So, I'll just agree that there is not a sharp line between seeing and understanding, which does not mean that there is not a distinction to be made.

I could pick at the wording. But I broadly agree. The issue arises in "Percipients do determine their objects". "Determine" and "determinate" are more complicated than they seem. An idealist would take "determine" in that sentence in the sense that a law-maker determines the law. A realist would take it in the sense that a scientist determines the level of pollution in a river.When the OP says "a world that is fully real and determinate independently of mind", what could 'determinate' mean in a world containing no perceivers? How could something be determined when there is no one there to determine it? Percipients do determine their objects. If they could not do that they could not survive. It seems to follow that things were determinable , just as they were visible and understandable, but obviously not seen, understood or determinate, prior to the advent of percipients. — Janus -

Ludwig V

2.5k

Ludwig V

2.5k

I think that may be common ground. The issue may be what the implications are. I think we have also agreed that our knowledge of how the world was before evolution kicked in, or percipients or homo sapiens appeared is a matter of extrapolating or projecting what we know (present tense). I've suggested the format of these exercises is a counter-factual conditional. If there had been observers, this is what they would have observed. (Berkeley accepts counterfactuals as compatible with his idealism, so I am not presenting it in the way of refutation.)So though we know that prior to the evolution of life there must have been a Universe with no intelligent beings in it, or that there are empty rooms with no inhabitants, or objects unseen by any eye. What their existence might be outside of any perspective is meaningless and unintelligible, as a matter of both fact and principle. — Wayfarer

This is where the distinction between Cambridge changes or relations and non-Cambridge changes or relations kicks in. For me, the "mental aspect" of reality is a Cambridge relation, that is, that the world before percipients and observers was constituted by objects and their relations.But what we know of its existence is inextricably bound by and to the mind we have, and so, in that sense, reality is not straightforwardly objective. It is not solely constituted by objects and their relations. Reality has an inextricably mental aspect, which itself is never revealed in empirical analysis. — Wayfarer

There's an additional divergence between us. You have denied that the mental acts required to establish our perspective on reality need to be carried out by any particular people. I get the impression that the "noetic act" needs to exist, but its existence is independent of actual people. I just don't get that.

I can just about get my head around "conditions of the possibility of knowledge". I've never had a firm grip on what metaphysics is supposed to be. My philosophical education was most remiss about that.These aren’t speculative metaphysical questions — they are conditions of possibility for scientific knowledge itself. Ignore them, and you don’t avoid metaphysics — you fall into it unwittingly. 'No metaphysics' ends up becoming a particularly poor metaphysics. — Wayfarer

That's all fine, until we get to the "it neither exists nor doesn't exist". It is true that nothing can be said about "unknown unknown", except that nothing can be said - or known - about them. Very little, but not nothing, can be said about "known unknowns". I would say, however, that we know that both exist.I’m not denying the reality of the universe prior to observation — I’m saying that what it is, apart from any possible mode of perception, conception, or representation, is not something that science can tell us, because science already presupposes intelligibility, structure, and observation. That is Kant's 'in itself' - to which I add, it neither exists nor doesn't exist. Nothing can be said about it. — Wayfarer

In real life, we discover both kinds as we go along. The existence of these is one of the things that tells me that there is more to the world than what we think about it. But it's not a category - it's a process. We incorporate them into what we already know, and we know that it is very likely that we will come across more as we go on.

Now, here's another point of divergence. In the 17th century, scientists foreswore the hidden realities of the (Aristotelian) scholastics. The function of science was to understand the realities that we actually experience - except those things that we experience that were not amenable to mathematical treatment - but that was treated as a marginal note. So science was about reality as it appears to us - so about appearances. This got confused by philosophers with their idea of appearances as curious phenomena that hid reality from us. So you remark about "knowledge of appearances" is ambiguous. For science, there is no distinction between appearance and reality. The idea that there are two distinct categories of - I'll call it existence - appearance and reality, is a philosophical invention. In reality, appearances are real and reality is what appears to us. So, the distinction between appearances and reality unconditioned by perspective is a chimera.That’s the critical point: science gives us knowledge of appearances, not of reality unconditioned by perspective. When we forget this distinction, we turn methodological naturalism into a metaphysical doctrine — and mistake the limits of our mode of knowing for the limits of what is. — Wayfarer

Yes, of course appearances are not reality because they are misleading. Truth is, sometimes they are and sometimes they aren't. Philosophy wants to forget the former, but we ought to remember it. This is important to us and to our discussion, because it is the misleading appearances that enable us to identify the limits of our mode of knowing. -

Gnomon

4.4k

Gnomon

4.4k

Yes, according to modern cosmology, the physical universe existed for about 10 billion years without any animation or "cognition" : just malleable matter & causal energy gradually evolving & experimenting with new forms of being ; ways of existing. So, you could say that the universe was not awake or aware until the last 4 billion years : the fourth trimester. Could that pre-conscious era be described metaphorically as Gestation : the period between Conception and Birth?On the empirical level, of course we say the cosmos existed long before us. But from the standpoint of critical philosophy, what we mean by “cosmos,” “existence,” or “visibility” only makes sense within the framework of our cognitive faculties. — Wayfarer

The book I'm currently reading is entitled, The Sapient Cosmos, by James Glattfelder. It's published by Essentia Books, which produces "scholarly work relevant to metaphysical idealism". The author was trained as a physicist, and practiced as a mathematician. But he now goes beyond the pragmatic limits of both professions, to explore the world philosophically ; which is to say "meta-physically". He refers to his methodology as "Empirical Metaphysics". What he finds most interesting is the emergence of Meaning in a material world.

Greek "Cosmos" simply means orderly or organized, but it also seems to imply some Teleological Purpose. The Latin root of "Sapient" means, not just cognitive, but also "wise". At this 1/3 point of the book, I'm not sure if the appellation is intended to apply to the physical universe or to the Organizer, whose purpose is being implemented in material & mental forms. As far as I can tell, the author is simply presenting "brute facts", if you can call philosophical deductions factual. And he is not presenting "institutional facts" under the auspices of Science or Religion. Yet, the question remains : did cosmic Mind exist before the emergence of embodied personal Minds? Or, as some postulate, did our accidental (fortuitous) collective human minds merge into a Cosmic Mind?

Personally, I am not inclined to worship a sentient world, or the implicit Inventor of a "mind-created world", nor to join a social group centered on a relationship with a Cosmos that doesn't communicate or correspond with me. I'm just exploring the wider world to satisfy my own philosophical curiosity. Am I missing some deeper meaning here? :smile: -

Wayfarer

26.2kIn the 17th century, scientists foreswore the hidden realities of the (Aristotelian) scholastics. The function of science was to understand the realities that we actually experience - except those things that we experience that were not amenable to mathematical treatment - but that was treated as a marginal note. — Ludwig V

Wayfarer

26.2kIn the 17th century, scientists foreswore the hidden realities of the (Aristotelian) scholastics. The function of science was to understand the realities that we actually experience - except those things that we experience that were not amenable to mathematical treatment - but that was treated as a marginal note. — Ludwig V

The point of the Galilean method was that it was defined in terms of primary and secondary attributes of matter, instead of Aristotelian (meta)physics and its 'natural tendencies'. As well as being inextricably connected with the geocentric cosmology. This is all history, of course.

Galileo's primary qualities, also endorsed by Locke, were those attributes of matter such as mass, force, velocity, inertia and so on - which were amenable to mathematical measurement and representation. That was the essence of the 'new physics' that represented a complete break from the earlier model.

For Galileo, how things appeared, on the other hand - color, taste, scent, and so on - were assigned to the mind of the individual. So here was a dualism of a completely different kind to what you're suggesting - between the measurable attributes of bodies, understood as objectively real, the same for all observers, as opposed to how they appeared, which was assigned to the individual mind, and so 'subjectivised'. This is the genesis of the 'Cartesian division' which has been subject to much commentary. Thomas Nagel put it like this:

The modern mind-body problem arose out of the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century, as a direct result of the concept of objective physical reality that drove that revolution. Galileo and Descartes made the crucial conceptual division by proposing that physical science should provide a mathematically precise quantitative description of an external reality extended in space and time, a description limited to spatiotemporal primary qualities such as shape, size, and motion, and to laws governing the relations among them. Subjective appearances, on the other hand -- how this physical world appears to human perception -- were assigned to the mind, and the secondary qualities like color, sound, and smell were to be analyzed relationally, in terms of the power of physical things, acting on the senses, to produce those appearances in the minds of observers. It was essential to leave out or subtract subjective appearances and the human mind -- as well as human intentions and purposes -- from the physical world in order to permit this powerful but austere spatiotemporal conception of objective physical reality to develop. — Mind and Cosmos, Pp 35-36

I can just about get my head around "conditions of the possibility of knowledge". I've never had a firm grip on what metaphysics is supposed to be. My philosophical education was most remiss about that. — Ludwig V

I understand that. I was introduced to Kant via an unorthodox route, through a 1950's book called The Central Philosophy of Buddhism, T.R.V. Murti. It has extensive comparisons with the European idealists and the 'Middle Way' (Madhyamaka) philosophy of a semi-legendary figure called Nāgārjuna (memorialised as 'the second Buddha', living in around the first century C.E. although dates are unknown.) Murti's book as fallen out of favour for being overly eurocentric (Murti having been Oxford-trained.) But it was one of those books which for me was a profound part of my spiritual and philosophical formation. It enabled me to see the link between meditative awareness and Kantian idealism.

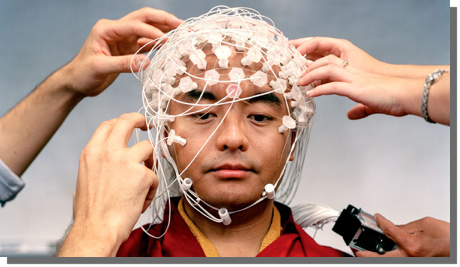

Buddhism has always been aware of the way the mind creates (or constructs) our world. That is why there has been extensive consultation between contemporary Buddhist scholarship, psychologists, and neuroscience (see The Mind-Life Institute). But Buddhism doesn't rely on scientific apparatus to attain its insights - it relies on highly-trained awareness to discern these insights about the constructive activities of the mind – although, that said, neuroscientists have devoted resources to exploring the effects of meditation on the mind:

Mingyur Rinpoche participating in experimental analysis of meditation

An AI-generated description of the parallels between Kant and Buddhist philosophy:

Murti draws a strong parallel between Nāgārjuna’s Madhyamaka philosophy and Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. Both begin with the insight that our experience of the world is structured by the mind and that we never encounter reality as it is in itself. For Kant, this leads to the distinction between phenomena (what appears to us) and noumena (the in-itself), showing that the categories of the understanding shape experience. Nāgārjuna similarly shows that all concepts and views are dependent and relational—empty of inherent nature or intrinsic reality (śūnyatā). Where Kant outlines the transcendental conditions of experience, Nāgārjuna critiques all fixed views, including metaphysical and epistemological views, to reveal the dependently-originated and non-substantial nature of all appearances.

I know there's a lot to take on there - both Kant and Nāgārjuna's texts have engendered huge volumes of commentary - but the key takeway is that both analyse the role of cognition in the construction of experience.

From the reactions to this OP, I'm realizing that it's a very difficult argument to present clearly. Broadly speaking, it's a transcendental argument—that is, it begins not with claims about what exists, but with an analysis of experience and cognition, and then asks: what must be the case for such experience to be possible? (This is why it is epistemological rather than ontological.)

One of the key implications is that we are not passive observers of a pre-given world, but active participants in the constitution of the world as we know and live it. To grasp this, we have to reflect on the role our own minds play in shaping the structures of experience—our world of lived meanings. This is precisely where phenomenology enters the picture, since it offers a disciplined way of examining experience from within, rather than assuming it as something merely external or objective. Hence the requirement for a changed perspective, not simply the acquisition of some propositional knowledge.

But that's a larger discussion. I've said enough for now.

Yes, according to modern cosmology, the physical universe existed for about 10 billion years without any animation or "cognition" : just malleable matter & causal energy gradually evolving & experimenting with new forms of being ; ways of existing. — Gnomon

Where does the measure 'years' originate, if not through the human experience of the time taken for the Earth to rotate the Sun?

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum