-

Janus

18kHence Penrose’s insistence that quantum physics is just wrong - because of his unshakeable conviction in scientific realism. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kHence Penrose’s insistence that quantum physics is just wrong - because of his unshakeable conviction in scientific realism. — Wayfarer

I think this is a bit misleading. Here Penrose says that what he means is that QT is incomplete, and when he says 'wrong' he admits he is being "blatant". Also his target for wrongness is not QT as such, but a specific interpretation which claims that it is consciousness which collapses the wave function. -

Apustimelogist

946Whereas more idealistically-tinged interpretations are compatible with the observations without having to question the theory. — Wayfarer

Apustimelogist

946Whereas more idealistically-tinged interpretations are compatible with the observations without having to question the theory. — Wayfarer

There's various realist positions that don't actually question the theory either! -

Wayfarer

26.2kThe point remains.He doesn’t single out the ‘consciousness causes collapse’ theory. His objections are pretty straightforward:

Wayfarer

26.2kThe point remains.He doesn’t single out the ‘consciousness causes collapse’ theory. His objections are pretty straightforward:

Discover Magazine: In quantum mechanics an object can exist in many states at once, which sounds crazy. The quantum description of the world seems completely contrary to the world as we experience it.

Sir Roger Penrose: It doesn’t make any sense, and there is a simple reason. You see, the mathematics of quantum mechanics has two parts to it. One is the evolution of a quantum system, which is described extremely precisely and accurately by the Schrödinger equation. That equation tells you this: If you know what the state of the system is now, you can calculate what it will be doing 10 minutes from now. However, there is the second part of quantum mechanics — the thing that happens when you want to make a measurement. Instead of getting a single answer, you use the equation to work out the probabilities of certain outcomes. The results don’t say, “This is what the world is doing.” Instead, they just describe the probability of its doing any one thing. The equation should describe the world in a completely deterministic way, but it doesn’t — Ref

His objection is philosophical: the equation should describe the world in a completely deterministic way; they don’t describe ‘what the world is doing’. But what if ‘the world’ is not fully determined by physics? What if it is in some fundamental sense truly probabilistic, not entirely fixed? He doesn’t seem to be able to even admit the possibility.

Anyway - enough with quantum intepretations. The only relevance to the OP is that physicists will sometimes mention Berkeley as an example of a kind of radical idealism, that theories of observation seem to suggest in some respects. -

Janus

18kHis objection is philosophical: the equation should describe the world in a completely deterministic way; they don’t describe ‘what the world is doing’. But what if ‘the world’ is not fully determined by physics? What if it is in some fundamental sense truly probabilistic, not entirely fixed? He doesn’t seem to be able to even admit the possibility. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kHis objection is philosophical: the equation should describe the world in a completely deterministic way; they don’t describe ‘what the world is doing’. But what if ‘the world’ is not fully determined by physics? What if it is in some fundamental sense truly probabilistic, not entirely fixed? He doesn’t seem to be able to even admit the possibility. — Wayfarer

This doesn't seem to be true:

Penrose’s attack is directed at determinism and materialism, still dominating the scientific environment and, in particular, neurosciences and believing to be able to reproduce human thought in a computer: «I have my reasons not to believe in this. Some actions of the human thought may be certainly be simulated computationally. For example, the sum of two numbers or even more complex arithmetic and algebraic operations. But human thought goes beyond these things when it becomes important to understand the meaning of that in which we are involved».

From Here -

Janus

18kNot sure which direct quotation you are referring to. If you mean his saying that the equation should describe the world in a deterministic way, I would interpret that as meaning that, given that the predictive success of QT is unparalleled, and given that the usefulness of any scientific theory consists in its predictive power, he concludes it must be incomplete.

Janus

18kNot sure which direct quotation you are referring to. If you mean his saying that the equation should describe the world in a deterministic way, I would interpret that as meaning that, given that the predictive success of QT is unparalleled, and given that the usefulness of any scientific theory consists in its predictive power, he concludes it must be incomplete.

The quoted passage just shows that Penrose is not a rigid determinist, and although Penrose is not quoted as explicitly saying it, according to the author of the article his attack is on the determinism and materialism that dominates the scientific environment, which I would have though is well in line with your ideas on the subject. -

Wayfarer

26.2kThe quoted passage just shows that Penrose is not a rigid determinist, — Janus

Wayfarer

26.2kThe quoted passage just shows that Penrose is not a rigid determinist, — Janus

I understand that Roger Penrose is not a materialist — if anything, he leans toward mathematical Platonism. But like Einstein, he is staunchly realist: they both believe that the world just is a certain way, and that the task of physics is to discover what that way is. Neither can reconcile themselves to the fundamentally stochastic character of quantum physics, nor to the philosophical implications of the uncertainty principle, which seem to undercut their conviction that nature has a definite, determinate structure. Einstein once remarked that if quantum theory were correct, he would have trouble saying what physics was even about any more.

Consider two of the better popular accounts of this dispute: Quantum: Einstein, Bohr, and the Great Debate about the Nature of Reality by Manjit Kumar, and Uncertainty: Einstein, Heisenberg, Bohr, and the Struggle for the Soul of Science by David Lindley. The “great debate” in the first title and the “struggle for the soul of science” in the second are, at root, the same battle — a battle over objectivity. Can physics provide, and should it aim to provide, a truly objective account of the world? Realism tends to treat this as a yes-or-no question. And that’s where, I think, the problem lies.

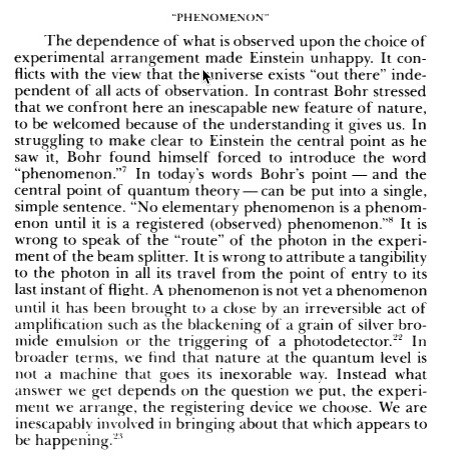

John Wheeler, 'Law without Law'

Which all stands to reason, by the way, because after all 'phenomenon' means 'what appears'. -

Apustimelogist

946Can physics provide, and should it aim to provide, a truly objective account of the world? Realism tends to treat this as a yes-or-no question. And that’s where, I think, the problem lies. — Wayfarer

Apustimelogist

946Can physics provide, and should it aim to provide, a truly objective account of the world? Realism tends to treat this as a yes-or-no question. And that’s where, I think, the problem lies. — Wayfarer

Again, a number of different realist accounts of quantum theory exist. There is no consensus on this at all that quantum theory has gotten rid of realism or something like that. -

boundless

760Kant doesn’t say our faculties impose order on “reality in itself” — only on the raw manifold of intuition as it is given to us. The in-itself is the source of that, but its true nature remains unknowable; what we know is the ordered phenomenal field that results from the mind’s structuring of the manifold of sensory impressions in accordance with its a priori forms and concepts. — Wayfarer

boundless

760Kant doesn’t say our faculties impose order on “reality in itself” — only on the raw manifold of intuition as it is given to us. The in-itself is the source of that, but its true nature remains unknowable; what we know is the ordered phenomenal field that results from the mind’s structuring of the manifold of sensory impressions in accordance with its a priori forms and concepts. — Wayfarer

The problem is if you claim that the reality beyond/prior to phenomena is completely unknowable you have either to accept (i) that the activity of the mind in ordering experience is enough to explain the order we see in phenomena or (ii) that (i) is false and you can't explain how the order we see arises. (ii) would be a form of skepticism. Both are forms of transcendental/epistemic idealism but only in the first option you do have an explanation of the regularities we see.

I'm aware that D'Espagnat differed with both Kant and Berkeley, but he did mention both. Berkeley's idealism is often mentioned by physicists as representing a kind of idealism that they wish to differentiate themselves from. But the point is - he's mentioned! — Wayfarer

Yes, certainly Kant and Kantians did have an important role. They provided arguments that helped even those that, at the end, disagreed. As I said, I agree that also thanks to Kant and so on, we now are more aware about the interpretative role of the mind and we are more aware that 'what appears to us' might not be 'what is really there'. -

boundless

760John Wheeler, 'Law without Law' — Wayfarer

boundless

760John Wheeler, 'Law without Law' — Wayfarer

IIRC John Wheeler is a good example of how sometimes physicists themselves provide writings that can be difficult exercises of exegesis, so to speak.

In the extract you quoted, for instance, Wheeler equates the terms 'registered' and 'observed' and this suggests that, according to him, mind is not necessary to 'collapse' the quantum statee. A registering device perhaps is also able to do that.

Two comments here:

(i) one can also say that the content of these 'recordings' become menaingful only when a mind gets to know them. If this is true, one would say that perhaps Wheeler's position implies idealism. Also, registering devices are human made so the activity of the mind actually might be considered a precondition for uniderstanding of their recordings.

(ii) even if (i) is wrong, however, the 'hard realist' objection of John Bell in his Against Measurement:

It would seem that the theory is exclusively concerned about ‘results of measurement’, and has nothing to say about anything else. What exactly qualifies some physical systems to play the role of ‘measurer’? Was the wavefunction of the world waiting to jump for thousands of millions of years until a single-celled living creature appeared? Or did it have to wait a little longer, for some better qualified system . . . with a PhD? If the theory is to apply to anything but highly idealised laboratory operations, are we not obliged to admit that more or less ‘measurement-like’ processes are going on more or less all the time, more or less everywhere? Do we not have jumping then all the time?

actually doesn't fare better if, instead of living or conscious beings, registering devices are those needed to collapse. In fact, it would be still quite strange that a complex inanimate physical object is necessary for the collapse. The world would still have 'waited' a lot to 'collapse'. If the world still had to wait in this case, why not waiting a bit more?

So, those views according to which a real collapse (not just 'decoherence') happens when some complex physical objects do not seem truly better for scientific realists than those which involve some kind of 'mind' (and as I said elsewhere, generally nowadays those who do say that mind has a role in collpase generally interpret collapse in a purely epistemic way, just as an update of knowledge/degree of belief and not that the mind has a 'causal effect' on a real object called 'wavefunction'). -

RussellA

2.7kI'm not sure about that. The gravity waves from black hole collisions can be perceived via gravity wave detection. Wouldn't that put them in the same category as, say, neutron stars? — RogueAI

RussellA

2.7kI'm not sure about that. The gravity waves from black hole collisions can be perceived via gravity wave detection. Wouldn't that put them in the same category as, say, neutron stars? — RogueAI

"Esse est percipi" can be translated as "to be is to be perceived”.

A Black Hole causes gravitational waves. We can perceive these gravitational waves. Does that mean we perceive the Black Hole?

In Air Traffic Control, the operator can perceive dots on their radar screens. Does that mean they perceive the planes that caused these dots? -

RussellA

2.7kAs regards black holes, Berkeley doesn’t reject inductive inference; in fact, his Principles of Human Knowledge and Three Dialogues show that he accepts the regularities of experience and the way we extend them to predict or explain things we haven’t directly sensed. — Wayfarer

RussellA

2.7kAs regards black holes, Berkeley doesn’t reject inductive inference; in fact, his Principles of Human Knowledge and Three Dialogues show that he accepts the regularities of experience and the way we extend them to predict or explain things we haven’t directly sensed. — Wayfarer

A Black Hole may emit gravitational waves, and it is these gravitational waves that we can perceive.

These gravitational waves "represent" the Black Hole that emitted them.

However, Berkeley rejects representationalism.

Both Reid and Berkeley reject ‘representationalism’, an epistemological position whereby we (mediately) perceive things in the world indirectly via ideas in our mind, on the grounds of anti-scepticism and common sense.

https://www.euppublishing.com/doi/abs/10.3366/jsp.2019.0242?journalCode=jsp

As you wrote:

What Berkeley objected to was the notion of an unknowable stuff underlying experience — an abstraction he believed served no explanatory purpose and in fact led to skepticism. — Wayfarer -

Wayfarer

26.2kI take measurement and observation to be observer-dependent. I mean, you could infer that many similar processes might be taking place without an observer, but you'd have to observe them to find out ;-)

Wayfarer

26.2kI take measurement and observation to be observer-dependent. I mean, you could infer that many similar processes might be taking place without an observer, but you'd have to observe them to find out ;-) -

RussellA

2.7kTwo meanings of ‘representation’ in play there. He objects to representative realism but I’m sure he would accept that the sight of smoke represents fire or a dangerous animal represents a threat. — Wayfarer

RussellA

2.7kTwo meanings of ‘representation’ in play there. He objects to representative realism but I’m sure he would accept that the sight of smoke represents fire or a dangerous animal represents a threat. — Wayfarer

There are also two meanings of "perceive".

One meaning of "perceive" is something through one of the five senses, such as "I perceive a red postbox" or "I perceive a loud noise".

Another meaning of perceive is to understand something in the mind, such as "I perceive she is getting bored".

In the sentence "I perceive smoke through my sense of sight and I perceive the smoke has been caused by fire" the word "perceive " has been used in two different ways.

In Berkeley's expression "esse est percipi", I understand the word "perceive" to refer to something through one of the five senses, not to something understood in the mind. -

boundless

760When one begins to say that 'measurement' is not a name for 'any physical interaction' (like RQM for instance does) but to mean something more complex, yeah it is not a stretch to think that 'mind' has some role.

boundless

760When one begins to say that 'measurement' is not a name for 'any physical interaction' (like RQM for instance does) but to mean something more complex, yeah it is not a stretch to think that 'mind' has some role.

I do believe for instance that Wheeler's view implies (perhaps unintentionally) a role of the 'mind'. -

Wayfarer

26.2kIn Berkeley's expression "esse est percipi", I understand the word "perceive" to refer to something through one of the five senses, not to something understood in the mind. — RussellA

Wayfarer

26.2kIn Berkeley's expression "esse est percipi", I understand the word "perceive" to refer to something through one of the five senses, not to something understood in the mind. — RussellA

But, for Berkeley, all that is real are spirits, which could be glossed as ‘perceiving beings’, and objects are ideas in minds.

But I don’t think that the corollary of that is that non-perceived objects cease to exist. They exist in the sight of God. (Do you know the limerick?)

The problem is always that ‘mind’ is outside a Wheeler’s usual term of reference. But Andrei Linde doesn’t hesitate to speak about it. -

RussellA

2.7kBut, for Berkeley, all that is real are spirits, which could be glossed as ‘perceiving beings’, and objects are ideas in minds. — Wayfarer

RussellA

2.7kBut, for Berkeley, all that is real are spirits, which could be glossed as ‘perceiving beings’, and objects are ideas in minds. — Wayfarer

I agree when you said:

George Berkeley (1685–1753) was an Irish philosopher and Anglican bishop best known for his philosophy of immaterialism — the view that physical objects exist only if perceived (summed up in the memorable aphorism ‘esse est percipi’). — Wayfarer

For Berkeley, objects exist as physical things in the world. -

boundless

760The problem is always that ‘mind’ is outside a Wheeler’s usual term of reference. But Andrei Linde doesn’t hesitate to speak about it. — Wayfarer

boundless

760The problem is always that ‘mind’ is outside a Wheeler’s usual term of reference. But Andrei Linde doesn’t hesitate to speak about it. — Wayfarer

Agreed. Wheeler, Bohr, Dirac etc were all ambiguos. One feels like they didn't want to assign mind a role but it is not too difficult to see it as an implicit conclusion of their reasoning.

Others like Linde, the QBists etc are not. IIRC, even John von Neumann wrote that the 'self' was responsible for collapse.

QM itself is basically silent. You are free to consider whatever you want to be an observer IMO. But the formalism does suggest that while you can apply QM to anything, you can't describe everything at the same time quantum mechanically - something must be described classically (I believe some physicist made a famous quote that says this).

But I don’t think that the corollary of that is that non-perceived objects cease to exist. They exist in the sight of God — Wayfarer

IMO it is more like God 'sends' to our minds (spirits) the right phenomena (mental contents) we have to percieve in a given time.

I have always asked myself how Berkeley's position fits (if it does) with traditional theistic metaphysics. Maybe some resident expert of that traditional view could explain this but I can't. To me Berkeley's view is something like traditional theism minus the physical world (which becomes entitely mental contents) but I am not sure. But I read about him many years ago. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kWhy would that necessarily be so? For all we know there is nothing more fundamental than quarks. There does seem to be a limit to the possibility of measurement, that much is known. — Janus

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kWhy would that necessarily be so? For all we know there is nothing more fundamental than quarks. There does seem to be a limit to the possibility of measurement, that much is known. — Janus

As I said, the the evidence is experiential. Not long ago atoms were the smallest particles.

Quarks have not actually been produced in isolation, because of the unintuitive nature of the strong force. So it is just the result of an unintuitive theory, that quarks are believed to be the most fundamental particles.

Measurement problems are temporary. -

Wayfarer

26.2kBut that’s the point of the OP! Aquinas was traditional (although for his day he was considered progressive.) But it was the beginning of secular modernism and the new ideas of empiricism that Berkeley was criticizing.

Wayfarer

26.2kBut that’s the point of the OP! Aquinas was traditional (although for his day he was considered progressive.) But it was the beginning of secular modernism and the new ideas of empiricism that Berkeley was criticizing. -

RussellA

2.7kI think that terminology is certainly not his. Have a browse of the Early Modern Texts translation provided in Ref 1. He’s quite the sophist. (I recommend the Dialogues.) — Wayfarer

RussellA

2.7kI think that terminology is certainly not his. Have a browse of the Early Modern Texts translation provided in Ref 1. He’s quite the sophist. (I recommend the Dialogues.) — Wayfarer

Berkeley does not believe that there are material objects in the world, athough he does believe that there are physical objects in the world.

From SEP - George Berkeley:

Berkeley defends idealism by attacking the materialist alternative. What exactly is the doctrine that he’s attacking? Readers should first note that “materialism” is here used to mean “the doctrine that material things exist”.

Thus, although there is no material world for Berkeley, there is a physical world, a world of ordinary objects. This world is mind-dependent, for it is composed of ideas, whose existence consists in being perceived. For ideas, and so for the physical world, esse est percipi. -

boundless

760Yes, I agree that Berkeley's target were secular materialists of his day.

boundless

760Yes, I agree that Berkeley's target were secular materialists of his day.

But IMO he used the empiricists' arguments (e.g. Locke) to show that phenomena are entirely mental and an external substratum was unnecessary.

However, it is quite different from what traditional theism says on matter. In that system we are acquinted with some features of the physical world. It is a type of direct (yet not naive) realism from our perspective. Of course, given that theism posits that everything is created by God, ultimately it is all ontologically dependent on the Mind of God.

Berkeley IMO took away the 'physical' using empiricist arguments. But in doing so he pointed to God as an explanation why there is intersubjective agreement, regularities in phenomena and so on.

IIRC, he also criticized other theists because, according to him, positing an external material substratum for phenomena 'weakens' so to speak God's role. -

boundless

760In many contexts physical and material are synonyms. Asserting that a mental content is 'physical' can be potentially misleading. I do understand why the SEP article does that but it is according to Berkeley everything is either minds or mental contents. I doubt that, say, also many physicalists would accept to call 'physical' something which is a mental content.

boundless

760In many contexts physical and material are synonyms. Asserting that a mental content is 'physical' can be potentially misleading. I do understand why the SEP article does that but it is according to Berkeley everything is either minds or mental contents. I doubt that, say, also many physicalists would accept to call 'physical' something which is a mental content. -

RussellA

2.7kIn many contexts physical and material are synonyms — boundless

RussellA

2.7kIn many contexts physical and material are synonyms — boundless

Yes, Materialism and Physicalism have other meanings as well.

But specifically for Berkeley, as an Immaterialist, he does not believe in a world of material substance, fundamental particles and forces, but he does believe in a world of physical form, bundles of ideas in the mind of God. -

boundless

760But specifically for Berkeley, as an Immaterialist, he does not believe in a world of material substance, fundamental particles and forces, but he does believe in a world of physical form, bundles of ideas in the mind of God. — RussellA

boundless

760But specifically for Berkeley, as an Immaterialist, he does not believe in a world of material substance, fundamental particles and forces, but he does believe in a world of physical form, bundles of ideas in the mind of God. — RussellA

I agree! I would add that then those ideas are also present in the minds of humans (and other created spirits) when the latter percieve the former. And God is the one who assures that our minds perceive the correct of those ideas at the proper times. -

Gnomon

4.4k

Gnomon

4.4k

Me too! But, his encyclopedic knowledge of "footnotes to Plato" seems to be second only to your own. So, I'm learning a lot about both objective and subjective aspects of the physical & meta-physical world. From his review of shamanism & psychedelic drugs, I learn more about human creativity, as evidenced in our ingrained love for fictional storytelling.Published by Essentia Foundation, which is Kastrup's publishing house. I like Glattfelder but my interests are a little more prosaic, he's a bit too far out when he gets into shamanism and psychedelics. — Wayfarer

Because of my rational-religion background though, I'm cautious about anything that smells like Mysticism & Spiritualism. That's why I spell the common term for a transcendent deity : G*D. For my BothAnd philosophy, it combines the philosophical concepts of Brahman (infinite & impersonal) and Atman (local & personal). What Glattfelder calls the Sapient Cosmos is to me more like Lao Tse's Tao. The First Cause of our universe necessarily had the Potential for Sentience & Sapience, but I would reserve the term "sapient" for someone we could communicate with, mind to mind. :smile:

PS___ Besides, he describes a primary role for Information --- my own personal pet --- in his philosophy of a material world full of immaterial ideas.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- What is the difference between subjective idealism (e.g. Berkeley) and absolute idealism (e.g. Hegel

- What does this philosophical woody allen movie clip mean? (german idealism)

- Idealism and "group solipsism" (why solipsim could still be the case even if there are other minds)

- Rationalism or Empiricism (or Transcendental Idealism)?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum