-

bert1

2.2kEvery theory of mind has some problem, — Relativist

bert1

2.2kEvery theory of mind has some problem, — Relativist

Absolutely. It's a matter of picking the least problematic. Or not picking at all. I think some kind of panpsychic property dualism is the most sustainable, but that has plenty of problems as well. I think for some of us (by 'us' I mean the hard-problem mongers on the forum), the conceptual issues around emergence seem so hard, clear and intractable that they can be provisionally discarded in favour of exploring other options. -

Relativist

3.6k

Relativist

3.6k -

180 Proof

16.5k

180 Proof

16.5k

:100:Physicalism is the [paradigm] that is most consistent with everything we do know through science about the mind-body relationship. More significantly: physicalism is consistent with everything else we know about the world - outside of minds. — Relativist -

Wayfarer

26.2kYour burden is to show that some aspect of mental processing cannot possibly be grounded in the physical. In this instance, you were suggesting that logical reasoning cannot be accounted for under physicalism. I was merely explaining why I think it can. If you think this inadequate, then explain what you think I've overlooked. If there's insufficient detail, I can explain a bit more deeply. — Relativist

Wayfarer

26.2kYour burden is to show that some aspect of mental processing cannot possibly be grounded in the physical. In this instance, you were suggesting that logical reasoning cannot be accounted for under physicalism. I was merely explaining why I think it can. If you think this inadequate, then explain what you think I've overlooked. If there's insufficient detail, I can explain a bit more deeply. — Relativist

What you’re overlooking is the distinction between causal explanation and normative explanation.

Physicalism gives you causal accounts of how neurons fire, how circuits activate, how information gets processed. None of that touches the normative structure of logical reasoning—the “oughts” built into validity, soundness, and necessity.

A physical description can tell you why a system outputs a certain conclusion (because certain neurons fired, or certain physical states occurred), but it can’t tell you whether that conclusion is valid, follows, or is logically required. Those are not causal properties; they’re normative relations between propositions.

And the point is that the science of determining causal relations relies on normative judgements.

I was simply giving an example of how meaning is attached to experience, in this case: a sensory experience. In this particular case, pain is clearly linked to intentional behavior: it's an experience to be avoided. — Relativist

I understand that, but it is too simplistic an example to support the contention. The simple association of words with sensations hardly amounts to a model of language. -

Wayfarer

26.2kMaths is not about brains, it is about abstract structure inferred in what we see in the world, the rules of math are about that abstract structure; that does not mean that how we use maths and the reason we are able to do math is not instantiated in brains. Logical necessity is not about neural tissue, it is part of abilities to talk about abstract structure we see in the world. But this does not mean that this ability and why it comes about, how it works, is not instantiated by, realized by neural tissue and physical stuff using descriptions which themselves invoke different levels of explanation and abstraction. — Apustimelogist

Wayfarer

26.2kMaths is not about brains, it is about abstract structure inferred in what we see in the world, the rules of math are about that abstract structure; that does not mean that how we use maths and the reason we are able to do math is not instantiated in brains. Logical necessity is not about neural tissue, it is part of abilities to talk about abstract structure we see in the world. But this does not mean that this ability and why it comes about, how it works, is not instantiated by, realized by neural tissue and physical stuff using descriptions which themselves invoke different levels of explanation and abstraction. — Apustimelogist

An instantiation is an instance of something; a rule book is an instantiation of the rules which it describes. A chess game is an instantiation of the game of chess. But that doesn't entail that what is instantiated is material or physical, even if the pieces are. For that matter, chess can be played without any physical pieces (indeed I recall reading in a James Michener book that Arabs used to play mental chess crossing the desert on camels with no board, although I find that ability unfathomable even though I know how to play chess. Chess masters such as Magnus Carlson play simutaneous blindfold games, even more astonishing.)

What you're arguing is, look, we have ideas, we can grasp numbers and logical laws, but the brain is physical, these ideas are 'instantiated' in the physical brain - therefore ideas have a physical basis or cause or dependency. Even if we can't really grasp how neurological activities give rise to ideas because of the brain's complexity, you think this allows you to say that they're still physical in principle. This is 'neural reductionism'.

"Neural Reductionism is the philosophical position that mental states, processes, and events (such as thoughts, feelings, memories, and consciousness) can be fully explained by, or reduced to, physical neural states and processes in the brain. In its simplest form, it posits that the mind is the brain." (Web definition.)

We can have descriptions, explanations of structure at various levels of abstraction about what we see, but they are all instantiated by and inferred by brains which are things in physical space-time. — Apustimelogist

But the living brain is not a physical thing in space and time. Material objects fit that description - balls, bullets, pencils, computer screens, an endless category of things. And I agree that if you were a neuro-anatomist examining an extracted brain, or a neurosurgeon performing an operation on one, then you're legitimately treating a brain as an object in those contexts. But the brain in lived experience - your brain - is not an object. The brain-as-object is something posited from outside the field of experience. Consciousness never encounters its own brain. Rather it is a vital centre of the living, embodied subject of experience, embodied in a biological and cultural network of meaning and symbolic relationships. It in no way can be described in solely physical terms.

The reductionist view basically abstracts the brain as a physical object, tractable to neuroscience, because that is the way that neural reductionism has to see it. That is why it is 'reducing!' It wants to reduce the rich, multi-dimensional reality of lived experience to the equations of physics, which have provided so much mastery over the world of things. But in so doing, it has forgotten or lost the subject for whom it is meaningful.

Furthermore, there's a sound argument for the fact that space and time themselves are manufactured by the brain, as part of the means by which sensory data can be navigated by us. So to say the brain is 'in' space and time, is probably less accurate than to say that space and time are 'in' the brain. -

Relativist

3.6k

Relativist

3.6k

This is an outdated objection to physicalism. Here's the boilerplate response:Physicalism gives you causal accounts of how neurons fire, how circuits activate, how information gets processed. None of that touches the normative structure of logical reasoning—the “oughts” built into validity, soundness, and necessity. — Wayfarer

"Oughts", intentions, and beliefs are dispositions. Being disposed to do X, means that under suitable circumstances, the individual will do X. X can be a thought.

Logical reasoning is guided by dispositions (beliefs) about entailments, conjunctions, disjunctions, etc.

Model of LANGUAGE?! Are you seriously suggesting that if I can't provide a bottom up account of the development or grasping of a language model, that this falsifies physicalism? That's ludicrous.I understand that, but it is too simplistic an example to support the contention. The simple association of words with sensations hardly amounts to a model of language. — Wayfarer

The fact that language can be interpreted by AI is sufficient to demonstrate that language is consistent with physicalism. Language doesn't mean anything to a machine- that's the one genuine difference, and that's why I focused on meaning. Incidentally, AI can engage in logical reasoning.

Instead of trying to falsify physicalism, you seem to be simply providing reasons why you are unconvinced. This comes off as arguments from incredulity.

As I told you, I'm not trying to convince you of anything. I embrace physicalism because it's the best explanation for all facts (including, but not limited to, science facts). Any mental behavior that is consistent with an algorithmic approach is consistent with physicalism. As I've admitted, feelings are not algorithmic- they are the sole, legitimate issue. They still don't falsify physicalism, but it's a legitimate problem. However, all theories of mind have problems. Those problems tend to be glossed over, or given ad hoc explanations (when one abandons naturalism, one feels free to entertain any magic that is logically possible). But that cannot result in a theory that is MORE plausible than physicalism, on the basis of its one problem and its speculative solutions. You aren't even in position to justifiably disagree, because you don't embrace any particular theory of mind (much less, a metaphysical theory). -

Wayfarer

26.2kThe fact that language can be interpreted by AI is sufficient to demonstrate that language is consistent with physicalism. — Relativist

Wayfarer

26.2kThe fact that language can be interpreted by AI is sufficient to demonstrate that language is consistent with physicalism. — Relativist

Not according to AI https://claude.ai/share/d20fdc96-dfad-44a1-9ef5-cbef895a5819

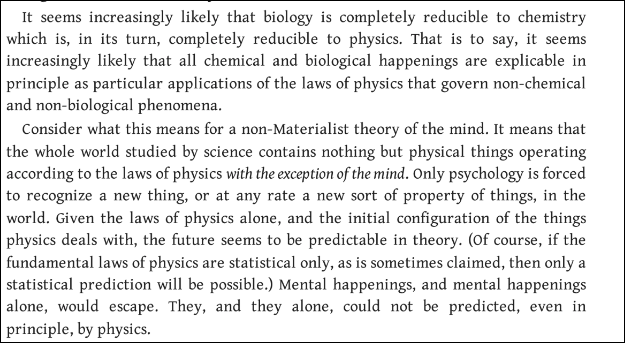

For clarity’s sake do agree with this depiction of materialism by D M Armstrong?

Might help to understand what is meant by physicalism.

(pressed for time will come back later) -

Wayfarer

26.2kLogical reasoning is guided by dispositions (beliefs) about entailments, conjunctions, disjunctions, etc — Relativist

Wayfarer

26.2kLogical reasoning is guided by dispositions (beliefs) about entailments, conjunctions, disjunctions, etc — Relativist

But being disposed to do or say something merely describes what someone ls likely to do. It doesn't describe what they ought to do. And it also reduces logic to psychology.

This comes off as arguments from incredulity. — Relativist

That definitely cuts both ways.

As I've admitted, feelings are not algorithmic- they are the sole, legitimate issue — Relativist

'This dam is a perfectly satisfactory, save for the hole in it.'

Comment on the Armstrong passage above. If you think it's right, what is right about it? If you think not, what is wrong with it? -

Apustimelogist

946What you're arguing is, look, we have ideas, we can grasp numbers and logical laws, but the brain is physical, these ideas are 'instantiated' in the physical brain - therefore ideas have a physical basis or cause or dependency. Even if we can't really grasp how neurological activities give rise to ideas because of the brain's complexity, you think this allows you to say that they're still physical in principle. This is 'neural reductionism'. — Wayfarer

Apustimelogist

946What you're arguing is, look, we have ideas, we can grasp numbers and logical laws, but the brain is physical, these ideas are 'instantiated' in the physical brain - therefore ideas have a physical basis or cause or dependency. Even if we can't really grasp how neurological activities give rise to ideas because of the brain's complexity, you think this allows you to say that they're still physical in principle. This is 'neural reductionism'. — Wayfarer

All I care about is whether the following is true:

"but the brain is physical, these ideas are 'instantiated' in the physical brain - therefore ideas have a physical basis or cause or dependency. Even if we can't really grasp how neurological activities give rise to ideas because of the brain's complexity"

If you want to say that math is about abstract relations not strictly about specific objects with enduring identities in space and time, thats fine. But as long as the quote or something like it is reasonable, I don't need to appeal to anything else additional or mysterious to ground it. I have in principle my story of where that comes from and that uses or even thoughts abput math are grounded in physical events. The rules of math don't come from, would not be derivable from more fundamental physical processes themselves. They are consequences of those physical processes performing inference about the structure of a world an organism exists in.

If I am not saying that the rules of math can be derived from the physical processes that underwrite cognition, and I am not saying we even have the capacity to model a human doing math yet, then I think its not necessarily the kind of neural reductionism you talk. But what it is saying is that there is nothing else mysterious or magical or dualistic or platonic going on, nothing other than brains performing abstract inferences about structure in the world.

Consciousness never encounters its own brain. — Wayfarer

This doesn't seem much different from the fact that experientially I will never encounter or pick out an individual electron. That shouldn't stop me from saying they are there. Neither do I see any reason to say that the richness of my experiences are a kind of functional structure occurring within the vicinity of my brain.

The reductionist view basically abstracts the brain as a physical object, tractable to neuroscience, because that is the way that neural reductionism has to see it. That is why it is 'reducing!' It wants to reduce the rich, multi-dimensional reality of lived experience to the equations of physics, which have provided so much mastery over the world of things. But in so doing, it has forgotten or lost the subject for whom it is meaningful. — Wayfarer

Your view seems to think there is some weird mutual exclusivity here when there isn't. You can think of the world is physical and talk about the richness of your own experience, study phenomenology, talk about existentialism, meditate, take LSD, listen to the Doors.

It in no way can be described in solely physical terms. — Wayfarer

Yes, and I have no desire to describe the majority if things in terms if fundamental physics.

And I am starting to suspect that your view is about to become uninteresting. What i interesting is something like substance dualists, not the claim that we shouldn't describe everything in terms of fundamental physics. Its uninteresting because I think most people don't take that view, even people who think of the world as fundamentally physical.

Furthermore, there's a sound argument for the fact that space and time themselves are manufactured by the brain, as part of the means by which sensory data can be navigated by us. — Wayfarer

Space and time are inferred. If we were arbitrarily constructing space and time then there would be no reason that it should help us navigate sensory data Space and time are structure of the world we infer througj sensory data. -

Wayfarer

26.2kI think most people don't take that view, even people who think of the world as fundamentally physical. — Apustimelogist

Wayfarer

26.2kI think most people don't take that view, even people who think of the world as fundamentally physical. — Apustimelogist

What about the boxed quote above in support of materialist theory of mind. Do you think it is basically correct? Or if not what’s wrong with it?

And, you haven't countered the argument I put to you, only re-stated your conviction that 'whatever exists must be physical'. -

Relativist

3.6k

Relativist

3.6k

Not merely "likely" - it's a certainty, given the right conditions. As I said, an "ought" is a belief/disposition. Believing that you ought to pay for your groceries (rather than steal them) will result in your paying for your groceries, unless other factors are present (eg you're hungry and destitute).But being disposed to do or say something merely describes what someone ls likely to do. It doesn't describe what they ought to do. — Wayfarer

More generally, this directly relates to "free will". Physicalism entails compatibilism: any choice you make will be the product of deterministic forces, a set beliefs (dispositions) that are weighed by the mental machinery, and can only produce one specific result. In hindsight, it only SEEMS like a different could have been made. In actuality, no other choice could have been made, given the set of dispositions that existed when the choice was made. So the collective set of dispositions necessarily leads to whatever choice that is actually taken.

No, not in the context of our discussion. I'm not trying to persuade you that physicalism is true. I was satisfied to agree to disagree, for reasons I had stated. But you refused to do that, and could not respect my position because you were confident you could demonstrate physicalism is false. My only task is to defend the reasonableness of my position. Your insult "disposed" me to continue the conversation, even after you stopped responding.This comes off as arguments from incredulity.

— Relativist

That definitely cuts both ways. — Wayfarer

I already did:This dam is a perfectly satisfactory, save for the hole in it.'

Comment on the Armstrong passage above. If you think it's right, what is right about it? If you think not, what is wrong with it? — Wayfarer

However, all theories of mind have problems. Those problems tend to be glossed over, or given ad hoc explanations (when one abandons naturalism, one feels free to entertain any magic that is logically possible). But that cannot result in a theory that is MORE plausible than physicalism*, on the basis of its one problem and its speculative solutions. You aren't even in position to justifiably disagree, because you don't embrace any particular theory of mind (much less, a metaphysical theory). — Relativist

*Perhaps you forgot: I embrace physicalism (generally, not just as a theory of mind) as an Inference to Best Explanation for all facts. You can defeat this only by providing an alternative that better explains the facts. -

Relativist

3.6kFor clarity’s sake do agree with this depiction of materialism by D M Armstrong?

Relativist

3.6kFor clarity’s sake do agree with this depiction of materialism by D M Armstrong?

Might help to understand what is meant by physicalism. — Wayfarer

I hadn't seem this post when I gave my prior reply.

I mostly agree with it, but have a problem with the terminology.

Regarding a definition, I recall that you quibbled with the definition of "physical". "Naturalism", as I defined it, dispenses with the semantics debate. -

Wayfarer

26.2kI mostly agree with it — Relativist

Wayfarer

26.2kI mostly agree with it — Relativist

(Armstrong quote) Do you know why I would not agree? I’ll recap - because it treats ‘mind’ as being on par with ‘the objects of physics and chemistry’. Do you know why I fault that?

I embrace physicalism (generally, not just as a theory of mind) as an Inference to Best Explanation for all facts. — Relativist

Except for the nature of mind and the felt nature of experience, right? You’ve acknowledged that in various places as I understand it.

You aren't even in position to justifiably disagree, because you don't embrace any particular theory of mind (much less, a metaphysical theory). — Relativist

That is a virtue as far as I’m concerned. -

Relativist

3.6kYes, I'm aware that you believe the mind is not physical, and therefore not on par with physics and chemistry. But the extent of what you told me you believe about mind is just this negative (supposed) fact: it's not physical. This means you answer no positive questions, account for no aspects of reality, so it's logically impossible for this singular negative fact to constitute a better explanation for reality (including, but not limited to, mind) than a comprehensive metaphysical theory.

Relativist

3.6kYes, I'm aware that you believe the mind is not physical, and therefore not on par with physics and chemistry. But the extent of what you told me you believe about mind is just this negative (supposed) fact: it's not physical. This means you answer no positive questions, account for no aspects of reality, so it's logically impossible for this singular negative fact to constitute a better explanation for reality (including, but not limited to, mind) than a comprehensive metaphysical theory.

I also do understand that you don't have much interest in a general metaphysical theory, and I'm fine with that. But you haven't grasped that this means you aren't positioned to judge my inferrence to best explanation. Instead, you seem to think that your objections to a physicalist account of mind are so objectively strong that no well-informed, rational person could fall for it. -

Wayfarer

26.2kYes, I'm aware that you believe the mind is not physical, and therefore not on par with physics and chemistry. But the extent of what you told me you believe about mind is just this negative (supposed) fact: it's not physical. — Relativist

Wayfarer

26.2kYes, I'm aware that you believe the mind is not physical, and therefore not on par with physics and chemistry. But the extent of what you told me you believe about mind is just this negative (supposed) fact: it's not physical. — Relativist

You keep telling me what I'm not grasping, so I'll return the favour. The reason that the mind is not an object like those of physics or chemistry is because it is what we are. Cogito ergo sum, as Descartes correctly observed, is the one indubitable fact of existence. The mind (observer, subject, consciousness) is the one utterly indbuitable fact of existence because it is that to whom all experience occurs. So, of course it's not in the frame, part of the picture, nor a 'mysterious entity' nor 'non-physical thing'. Now the entire phenomenological, idealist, Indian, and most contiental philosophy understands this in a way that Anglo physicalism cannot.

And for you, that's just an inconvenient detail, somethingt that doesn't fit with your otherwise 'best explanation for all the facts'. Whereas, to me, that invalidates the entire point of philosophy, as it excludes the very subject to whom philosophy is meaningful.

Martin Heidegger is a difficult philosopher and one who's books I have not read in full, But he does point to what he calls the 'forgetfulness of Being', saying that this is a deficiency or an absence at the centre of modern philosophy. And that this is not a matter of propostiional knowledge, but an fact about existence (therefore, 'existential'.) -

Apustimelogist

946And, you haven't countered the argument I put to you — Wayfarer

Apustimelogist

946And, you haven't countered the argument I put to you — Wayfarer

Which argument?

What about the boxed quote above in support of materialist theory of mind. Do you think it is basically correct? Or if not what’s wrong with it? — Wayfarer

Physics only predicts how things behave. Physics doesn't tell you about an "intrinsic" nature of things, and I dont think this is necessarily a barrier to a physicalist perspective. Given that, I dont think I should have any expectation that physics should tell me about what its like to feel something. The inexicability of qualia is not specifically anything to do with physics, it is inherently irreducible, inarticulable, and ive always thought that the brain itself and how it processes information will actually also give insights into why we cant articulate some things about the information we process and why we can articulate certain other things. This would be connected to the meta-problem of consciousness. -

Wayfarer

26.2kThe inexicability of qualia is not specifically anything to do with physics — Apustimelogist

Wayfarer

26.2kThe inexicability of qualia is not specifically anything to do with physics — Apustimelogist

Need I point out that this is not the Physics Forum? -

Apustimelogist

946

Apustimelogist

946 -

Punshhh

3.6k

Punshhh

3.6k

Sounds good, I do think it’s important to bring emotions into this, which involves the endocrine system of hormones and pheromones. So to put it simply, this is a way that the body, as distinct from the brain, is involved in being. Emotions can be triggered in the body ( this can cause a bit confusion because the brain is a physical organ, acting as a gland, independently of the mind), the body informs the being and mind through hormonal activity. Which often works through feelings, urges, emotional states. You only need to look at the oestrogen cycle to see how that occurs.1) illusionism - this means feelings are not directly physical because they exist exclusively in the mind- a mental construction. It depends only on mental causation (which I've defended). It also accounts for the action of pain-relievers, which mask the pain by interfering the brain's construction of the sensation.

So yes, feelings exist in the mind, to an extent. But I would suggest also that the mind isn’t consciousness, that consciousness is due to cellular activity (which does include the cells in the brain). But there is something about the being which draws all the instantiations of consciousness (from the cells) into the coherent form of an organism. This multicellular organism somehow acts as a singular conscious being. Who is then enhanced by the computational activity of the mind, hosted by the brain. And that feelings can occur in this instantiation, or singular conscious being, in complex and subtle ways among the complex interactions between the body, the mind and the emotions, acted out within consciousness (as described).

To an extent, but I see no reason that it may never be, we just haven’t invented the science yet. I come to this from the opposite end of the stick, I work within a complex ideological system of spirit, soul and mind distinct from the physical world, but which interacts with the physical via beings. Beings that are organisms present in the physical sphere. So bridge the gap between the two. There simply isn’t any science working here, there is very little literature and most of it is embedded in religious traditions. So all there is is some ideas worked out by people like me, Wayfarer and a number of others on the forum, and thinkers, or priests within the religious traditions who work with the ideology therein. A ragtag band, of misfits with no overarching scientific, or philosophical grounding (theology accepted). So I can understand the skepticism of people working with a more formal ideology.2) Feelings are due to some aspect of the world that has not been identified through science, and may never be. This is open-ended; it could be one or more properties or things. -

Punshhh

3.6k

Punshhh

3.6k

I think there is a difficulty in depicting the mind in this way. Because the brain is a physical organ. True when it is alive and consciousness it is much more than that, but that organ is present in spacetime.But the living brain is not a physical thing in space and time.

I would suggest that the brain hosts the mind, so is distinct from the mind, in that the brain is an apparatus performing the biological functions required for a mind to have a presence and interact within a physical body. So it is more appropriate to describe the mind as not a physical thing in space and time.

I hold that there is a mind independent of space and time, but that it is present in the world through being hosted by the brain (and the body). That the nature, or personality of that mind is formed alongside the body in the womb and is the body and mind and is and is not part of the world, simultaneously.

So that we find ourselves with a science and philosophy (in the Western tradition), covering only half of the story, the issue. The other half (the mind etc) has barely been discovered, or recognised. -

Wayfarer

26.2kI do see your point and there is a sense in which the brain is a physical organ which can be physically damaged, But in context the implication was that it is ‘just another physical thing’ which is what I’m calling into question. And I think you would find the physicalist would not allow that the mind and brain are conceptually seperable as that would imply dualism,

Wayfarer

26.2kI do see your point and there is a sense in which the brain is a physical organ which can be physically damaged, But in context the implication was that it is ‘just another physical thing’ which is what I’m calling into question. And I think you would find the physicalist would not allow that the mind and brain are conceptually seperable as that would imply dualism, -

Punshhh

3.6kYes, I see that. It’s so difficult to tease out these positions.

Punshhh

3.6kYes, I see that. It’s so difficult to tease out these positions.

The dualism point, for me depends on where one draws the line. It might be dualism, or monism depending on where one considers the divide between the two to be. So I don’t think this can be resolved, and shouldn’t be used as a means to shut down possibilities. -

Mww

5.4kPhysics doesn't tell you about an "intrinsic" nature of things…. — Apustimelogist

Mww

5.4kPhysics doesn't tell you about an "intrinsic" nature of things…. — Apustimelogist

At least one thing must have an intrinsic nature, such that there is a “you” physics doesn’t inform.

If physics…..

…..only predicts how things behave. — Apustimelogist

….and insofar as there is an intrinsic nature of at least one thing physics doesn’t inform, it follows physics cannot predict the behavior of the same “you” it doesn’t inform.

—————-

The thing with an intrinsic nature for which physics can neither inform nor predict with apodeitic certainty, with universality and absolute necessity, re: according to law, resides in the human brain, from which “you” originates. In order to reconcile contradictory theses, parsimony mandates another substantially different explanatory system for that which physics cannot address. Or, the “you”, not included in the explanatory domain of physics, must remain ever uninformed and unpredictable, which would immediately jeopardize the brain’s very use of the term itself, insofar as it there wouldn’t even be a “you” without it.

Which gives raison d’etre to the idea of an intrinsic nature as such, in this case, “you” as it relates to physics and is contained in the brain: there is a veritable plethora of evidence justifying the human being’s general distaste for being uninformed, to the extent that the brain will construct an explanatory system which satisfies the want for it.

So, no, physics hasn’t the means to predict that the brain would invent metaphysics, and physics hasn’t yet informed the brain of its own intrinsic nature by which that invention occurred, and, that there is a “you” to which it belongs.

But it gets worse than that. Physics cannot be used to explain how the brain originates that supposed domain of explanation having no ground whatsoever in the method by which physics does anything at all according to law.

And the fun part? The brain doesn't do physics, it merely operates in accordance with the discipline called “physics”, which was (gasp) invented by the very same intrinsic nature of the brain for which it is not the sufficiently explanatory method.

—————-

Of course, the answer is….there isn’t any “you” in the first place. None of the inventions of the brain, from itself, to explain itself, are really real. Which only leads to the question, if there isn’t any of that invented stuff in concreto, why is it that the brain makes it seem like there is? Every fargin’ thing the brain does seems to belong to a “you” of some time and place, such that it is incomprehensible that it never did, yet there is a not single one of them anywhere to be put in a box, to be charged a ticket to gawk at.

Why not grant to metaphysics legitimacy as an explanatory device, for no other reason than physics isn’t enough? I mean….it’s been done, however subconsciously, long before humans figured out how to write about it.

————-

Rhetorically speaking…. -

Apustimelogist

946

Apustimelogist

946

You have to realize that Wayfarer's brand of anti-physicalism is very different from yours. You are positing that there is something like a mental stuff and a physical stuff that are inherently different.

It can be confusing talking to Wayfarer because often he speaks as if this is what he is also suggesting, but he isn't. All he really wants to say is that we should not explain everything with physical concepts, and emphasize that non-physical concepts are defined non-physically. But even a physicalist can and I think generally does engage with concepts this way and so what he is arguing for is not philosophically interesting.

When you do end up probing Wayfarer on what he actually thinks about deep fundamental ontology, he will not endorse the kind of radical beliefs you do. He stays agnostic on that kind of thing and just says things like "the world beyond our senses is not as it really seems" or "We cannot engage with the world without concepts we have created", but he is never going to commit to a kind of substance dualism even though he sometimes speaks like he does. And he says he is not going to contradict accepted scientific consensus. He rarely tries to make it explicit that he is not actually a substance dualist or Kastrupian idealist. All he wants is to not conflate non-physical and physical concepts, nothing more. -

Relativist

3.6kI embrace physicalism (generally, not just as a theory of mind) as an Inference to Best Explanation for all facts.

Relativist

3.6kI embrace physicalism (generally, not just as a theory of mind) as an Inference to Best Explanation for all facts.

— Relativist

Except for the nature of mind and the felt nature of experience, right? You’ve acknowledged that in various places as I understand it. — Wayfarer

Then you misunderstood. I was open to an alternative that might be a better explanation for the "hard problem", but you didn't offer one. That's why I kept asking for more than the "negative fact" (not physicalism).

Try to understand this in terms of seeking an Inference to Best Explanation: that "negative fact" explained nothing. As I said then, it merely opened up infinitely many possibilities. But also, if anything is possible then it's also possible that there is an unknown natural solution - one that may even be inaccessible to scientific analysis. This is a dramatically smaller explanatory gap than leaving all possibilities open.

Some physicalists (including Armstrong) insist that all questions about the natural world will one day be discovered by science. I do not share that optimism. We may never determine the true ontology of the QM "measurement problem". String theory may be true, but it is empirically unverifiable. But there could easily be other aspects of reality that are beyond our capacity to explore. This rationalizes the assumption that the explanatory gap has a natural solution. I acknowledge this as a weakness, but it's minor compared to the alternatives.

Withholding judgement is always a respectable position. But you should be consistent and also withhold judgement on physicalism: it's not provably false; it has a great deal of explanatory power, and it's consistent with what we do know about neurology and the natural world.You aren't even in position to justifiably disagree, because you don't embrace any particular theory of mind (much less, a metaphysical theory).

— Relativist

That is a virtue as far as I’m concerned. — Wayfarer

Although I make a judgement, I don't rule out the possibility I'm wrong. It's odd that you rule out the possibility I'm right. -

Relativist

3.6kI hold that there is a mind independent of space and time, but that it is present in the world through being hosted by the brain (and the body). — Punshhh

Relativist

3.6kI hold that there is a mind independent of space and time, but that it is present in the world through being hosted by the brain (and the body). — Punshhh

Why do you believe that? What's your justification? What you describe sounds like dualism - is that indeed your position? Are you familiar with the interaction problem? -

Apustimelogist

946And I think you would find the physicalist would not allow that the mind and brain are conceptually seperable as that would imply dualism, — Wayfarer

Apustimelogist

946And I think you would find the physicalist would not allow that the mind and brain are conceptually seperable as that would imply dualism, — Wayfarer

No, I think most physicalists can acknowledge the conceptual separability between mind and brain, as well as a whole bunch of other conceptual distinctions in the vicinity of the same topic.

The physicalist wants to claim that when you zoom-in on the world and un-mix the convoluted causal structures, then you will find that everything is grounded in more fundamental events or structures describable and predictable by physics, and you will find no additional stuff behaving according to different principles. This doesn't invalidate conceptual distinctions, it just recognizes the hierarchical structure of scientific theories and the fact that no other competing theories describing mental substances exist or even plausibly exist that have any testable consequence.

My brand of physicalism is silent on the exact "intrinsic" nature of the world because that concept doesn't really have any articulable, consequential meaning or implication for anything other than being a kind of placeholder in one's metaphysics - scientific theories are descriptions that predict the behavior of the world as we see it. But I don't think that we need an articulable characterization of the "intrinsic" nature of the world in order to reiterate what I say in my second paragraph. In some ways then, this brand of physicalism is more like a family of scientific hypotheses against the kind of hypotheses that substance dualists would present.

Notice that experience is exactly as inarticulable as notions of "intrinsic" stuff. There is then no inherent or at least articulable contradiction between the ineffability of consciousness and the kind of "intrinsic" nature of the world that the physicalist would scaffold their descriptions on. A panpsychist would use the inability of physics to characterize "intrinsic" natures of the world as a gap where one can consistently inject consciousness.

My view instead is that if the inarticulability about "intrinsic" nature of the world and inarticulability about experience are indistinguishable, this shouldn't lead us to say that the intrinsic nature of the world is consciousness or experience, rather it should lead us to say that when we talk about experience, we are actually talking about something that is fundamentally underspecified and we don't have any conceptual structure to say anything meaningful about it or say what it it is other than something like it reflects a kind of informational structure grounded in some more fundamental causal structures when you zoom-in. This doesn't necessarily make it different from any other structures in reality, and the ineffability of consciousness is not distinguishable from (in)articulating about "intrinsic" natures regarding any other structure.

Nonetheless, given that consciousness is fundamentally grounded on brains for which we have various tools to describe their behavior, there is scope to examine why it is that we can or cannot articulate about various aspects of information in the brain, which might be linked to things like munchausen's trilemma, self-referentiality, primitive or indecomposable concepts, constrains on what makes a good representation, coarse-graining, the conditoonal-independence regarding Markov blankets, and limits on the determinacy of sensory processing, the inherently enactivist albeit predictive nature of description (e.g. language-as-use). This would also be linked to our inability to easily reduce qualitative experience to physical explanations in the same way we can with other more abstracted spatial structures we can identify when we see things.

One may be able to say that there is something that it is like to be a kind of structure in reality but there are strong limits on what this sentence can possible mean about an "intrinsic" nature of reality, and there is no necessary conflict with the hierarchical structure of scientific theories (with structures described by physics occupying a certain position) and any possible limits they have in explanation (such as the reasons in the above paragraph). -

Apustimelogist

946

Apustimelogist

946

The issue is that nothing tells you about or can articulate an "intrinsic" nature of things. Its not a specific issue of physics. Neither is it a specific issue of consciousness. In a p-zombie universe with no consciousness, physics doesn't tell you about the "intrinsic" nature of things anymore than it does in any other universe. Nonetheless, this p-zombie universe doesn't seem problematic for physicalism because articulable explanation seems to be exhausted by a hierarchical knowledge framework we have accumulated as humans where the physical sciences have a certain position in the hierarchy with regard to the description or more specifically the prediction of actual events that happen in the world.

Metaphysics is about articulable descriptions and when we get to the notion of "intrinsic" natures we can say very little that is not circular or very primitive and non-descript like "dualism is false". I think various kinds of positions on anti-physicalism kind of assume that descriptions and explanations come for free most of the time. But I don't think this is the case. All description and explanation occurs in some kind of context where there are limitations or constraints, ultimately shaped by how brains process and use information. If you no longer think explanations should come for free, I don't think you can be sure anymore that the ineffability of something like experience is [not] intrinsically linked to epistemic constraints as opposed to reflecting something fundamental about nature.

But then one has to also be mindful about what it means to say that explanations or descriptions or scientific theories are real within their own epistemic constraints. And there's no question for me that certain areas of knowledge will come with things like "strange-loops" which are fundamentally due to the limits on how information can be processed.

Edit: [ ] -

Wayfarer

26.2kThe physicalist wants to claim that when you zoom-in on the world and un-mix the convoluted causal structures, then you will find that everything is grounded in more fundamental events or structures describable and predictable by physics, and you will find no additional stuff behaving according to different principles. — Apustimelogist

Wayfarer

26.2kThe physicalist wants to claim that when you zoom-in on the world and un-mix the convoluted causal structures, then you will find that everything is grounded in more fundamental events or structures describable and predictable by physics, and you will find no additional stuff behaving according to different principles. — Apustimelogist

I well aware of physicalist claims, and that is a good description of it.

One of Charles Pinter's central arguments in Mind and the Cosmic Order is that science explains the world by decomposing it into simples—the smallest, causally interacting constituents: particles, fields, molecules, neurons. (This can be traced back to atoms and atomism, although the idea of a physical atom has since been displaced.) This method has delivered enormous explanatory power , but it also commits us to a very specific kind of explanation: one where wholes are derivative, and the only truly fundamental realities are the constituents and their interactions.

Charles Pinter highlights fundamental issue with this attitude. Organisms don’t perceive the world in terms of simples. The human and animal sensorium (the manifold of sensory impressions which constitute 'things' for animals and humans) works in terms of gestalts—unified, meaningful wholes: faces, trajectories, melodies, intentions, beings, and so on. These are not assembled bottom-up from atomic sensory “bits”; rather, they are the primary mode in which the world is disclosed to a subject. When we identify something, we identify a gestalt, not an assembly of simples. This is a basic fact of cognition.

A gestalt has properties that no list of constituent parts captures: unity, salience, meaning, intentional relevance. A melody is not found in the individual notes; a face is not found in the luminosity patches; a perceived threat is not found in isolated pixels or shapes. These features belong to the organization of the whole, not to the micro-level items. They, more than atomic simples, are the basic constituents of the 'life-world', the world of lived meaning. And Pinter demonstrates this is so, not just for humans, but even for insects.

The tension is this:

* Science’s ontology is formulated in terms of simples.

* Mind and perception operate in terms of gestalts.

(Hence you can see why I'm not appealing to 'non-physical substances'.)

A physicalist can say that gestalts somehow “emerge” from simples, but the challenge is to show how the features distinctive of gestalts—coherence, meaningfulness, aboutness—follow as a matter of explanation from the properties of the physical parts. Simply asserting neural correlates doesn’t do the philosophical work, because correlates explain when something occurs, not why its distinctive features exist at all.

The point is that the reductive strategy that works for chemistry or planetary motion is not obviously suited to phenomena whose defining characteristics are holistic, structured, and inherently perspectival. If explanation bottoms out in simples, yet consciousness and cognition are inherently gestalt-like, then either:

* the reductive framework is incomplete, or

* gestalts possess explanatory features not captured by simples, or

* a richer conception of nature is needed, in which organization, form, and perspective are not treated as secondary or derivative

This isn’t an argument against physics. It’s an argument that a scientific metaphysics based solely on simples faces a structural mismatch with the phenomena of mind, whose basic units are wholes rather than parts.

So while it may be true that 'we don't know the intrinsic nature of anything' that is far from the only problem with physicalism. As an explanatory paradigm, it methodically excludes the basis of meaning in cognition.

All description and explanation occurs in some kind of context where there are limitations or constraints, ultimately shaped by how brains process and use information. — Apustimelogist

Here, you're committing the 'mereological fallacy'. This is central to an infliuential book, The Philosophical Foundations of Neurosciences, Hacker and Bennett (philosopher and neuroscientist, respectively):

In Chap 3 of Part I - “The Mereological Fallacy in Neuroscience” - Bennett and Hacker set out a critical framework that is the pivot of the book. They argue that for some neuroscientists, the brain does all manner of things: it believes (Crick); interprets (Edelman); knows (Blakemore); poses questions to itself (Young); makes decisions (Damasio); contains symbols (Gregory) and represents information (Marr). Implicit in these assertions is a philosophical mistake, insofar as it unreasonably inflates the conception of the 'brain' by assigning to it powers and activities that are normally reserved for sentient beings. It is the degree to which these assertions depart from the norms of linguistic practice that sends up a red flag. The reason for objection is this: it is one thing to suggest on empirical grounds correlations between a subjective, complex whole (say, the activity of deciding and some particular physical part of that capacity, say, neural firings) but there is considerable objection to concluding that the part just is the whole. These claims are not false; rather, they are devoid of sense.

Wittgenstein remarked that it is only of a human being that it makes sense to say “it has sensations; it sees, is blind; hears, is deaf; is conscious or unconscious.” (Philosophical Investigations, § 281). The question whether brains think “is a philosophical question, not a scientific one” (p. 71). To attribute such capacities to brains is to commit what Bennett and Hacker identify as “the mereological fallacy”, that is, the fallacy of attributing to parts of an animal attributes that are properties of the whole being. Moreover, merely replacing the mind by the brain leaves intact the misguided Cartesian conception of the relationship between the mind and behavior, merely replacing the ethereal by grey glutinous matter.

You see, I think your approach is undermined by this reductionism, the conviction that basic physical level is the only real one, to the extent that you can't even consider any alternative. You simply assume that philosophy must defer to physics, as if that can't even be in question.

Pinter, Charles C. Mind and the Cosmic Order: How the Mind Creates the Features & Structure of All Things, and Why This Insight Transforms Physics. Cham (Switzerland): Springer, 2020

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum