-

RussellA

2.7kYour view seems to reject the representational aspect while still treating experience as epistemically primary, whereas I would want to reject both. — Esse Quam Videri

RussellA

2.7kYour view seems to reject the representational aspect while still treating experience as epistemically primary, whereas I would want to reject both. — Esse Quam Videri

As an Indirect Realist, it would be illogical to reject any representational aspect, and not sensible not to treat phenomenal experience as epistemically primary.

My understanding is that:

The Indirect Realist avoids external world scepticism by deriving concepts based on consistencies in these phenomenal experiences. Using these concepts, which can represent, the Indirect Realist can then rationally employ "inference to the best explanation” to draw conclusions about an external world causing these phenomenal experiences.

It can be said that there are three temporal stages in perception.

Stage one. Phenomenal experiences, such as when we look at a wavelength of 736nm

Stage two. Mental concepts based on phenomenal experiences, such as perceiving red light

Stage three. Judgements about what these concepts represent, such that red light represents stop.

Sense data is introduced at stage two. As Betrand Russell wrote in The Problems of Philosophy:

Let us give the name of "sense-data" to the things that are immediately known in sensation: such things as colours, sounds, smells, hardnesses, roughnesses, and so on. We shall give the name "sensation" to the experience of being immediately aware of these things .... If we are to know anything about the table, it must be by means of the sense-data - brown colour, oblong shape, smoothness, etc. -which we associate with the table.

It is in the nature of a judgement in stage three that any judgement could be wrong. This is why it is called a judgement. To negate all judgements because one judgement might be wrong would be to contradict the very meaning of the word.

All three stages are essential to both Indirect and Direct Realism.

As regards stage one, without phenomenal experiences, humans would be imprisoned in a dark and soundless room. As regards stage two, without the prior concept of ship, when looking at the singular instantiation of an object, no one would be able to say “I see a ship”. As regards stage three, no one would be able to judge that a set of perceived concepts represents a ship.

There is phenomenological Direct Realism (PDR), direct perception and direct cognition, and Semantic Direct Realism (SDR), indirect perception and direct cognition.

I would imagine that most Direct Realists on this thread believe in SDR, as few would not admit that when we see a ship we directly see the light entering the eye from the ship, in that, as has been said, we don't directly put our eyeball on the ship.

Both the Indirect Realist and SDR can say “I see a ship”, even though for both it is through the intermediary of light entering the eye, and for both illusions and hallucinations are possible. The linguistic expression “I see a ship” as part of a communal language can be understood by all those using the same language game, regardless of any metaphysical implications. If pressed, the IR may say “I see the wavelength of light as a ship” and the SDR may say “I see a ship by means of a wavelength of light”, but for convenience, to say “I see a ship” is perfectly understandable.

The Indirect Realist and the SDR differ in that the SDR believes that their judgements can transcend their phenomenal experiences, whereas the Indirect Realist doesn’t.

Between the mind and any external world are the five senses. The mind only knows what passes through these five senses. Therefore, for the Indirect Realist, anything we think we know about any external world comes indirectly from “inference to the best explanation”. However, for the Direct Realist, we are able to transcend these five senses and directly know about any external world.

One question for believers in SDR is how they explain their judgements are able to transcend their phenomenal experiences -

Hanover

15.3kBut also, let's assume that John's and Jane's screens output different colours in response to the same wavelengths of light, but in a consistent manner. Do you accept that a) they will both use the word "green" when asked to describe the colour of the grass and that b) there is a very real sense in which when they use the word "green" they are referring to the colour output by their screen (assuming, for the sake of argument, that naive realism is true). — Michael

Hanover

15.3kBut also, let's assume that John's and Jane's screens output different colours in response to the same wavelengths of light, but in a consistent manner. Do you accept that a) they will both use the word "green" when asked to describe the colour of the grass and that b) there is a very real sense in which when they use the word "green" they are referring to the colour output by their screen (assuming, for the sake of argument, that naive realism is true). — Michael

I think your thought experiment shows that the response to (b) is irrelevant. If X presents to me as rabbits and to you as cats, but we both call them ducks, then "ducks" follow our rules, namely that they are Xs, but it doesn't matter what it is independent of us or what we see. It just needs to follow a usage rule which drops out the necessity of identifying the underlying metaphysical constitution of the thing. The purpose in this is not to suggest the underlying thing doesn't have some constitution, but it's to understand that speaking about it gets us no where. The purpose of philosophy under this model isn't to understand every aspect of the world, but it's to understand what can be understood and to discuss only that.

So, to answer your questions (because I hate it when people don't directly answer yes or no questions when posed) : (a) - Yes and to (b) yes, but as to (b), the fact that they are "in a very real sense" referring to their beetle in their box doesn't mean we now get to understand what those beetles are. -

Michael

16.9kthe fact that they are "in a very real sense" referring to their beetle in their box doesn't mean we now get to understand what those beetles are. — Hanover

Michael

16.9kthe fact that they are "in a very real sense" referring to their beetle in their box doesn't mean we now get to understand what those beetles are. — Hanover

I'm not claiming that we do. I'm only showing that our words can, and do, refer to these beetles.

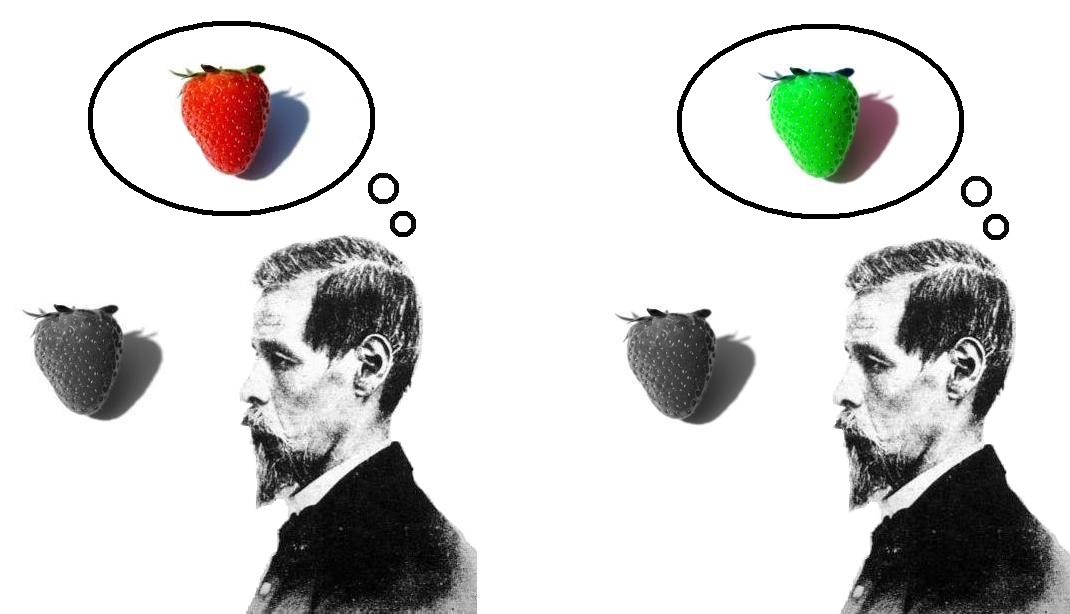

In a situation like the below, both may agree with the proposition "the strawberry is foo-coloured", and may even agree that the word "foo" (sometimes) refers to a disposition to reflect a particular wavelength of light, but I think it unproblematic to accept that the word "foo" also refers to the private phenomenal character of the individual's experience, even if neither can know the other's. If someone were to secretly surgically alter their eyes and/or brains such that the phenomenal character was switched then each would say "the strawberry is no longer foo-coloured" (and then be very confused when they measure the wavelength of light and detect no change).

-

Hanover

15.3kI'm not claiming that we do. I'm only showing that our words can, and do, refer to these beetles.

Hanover

15.3kI'm not claiming that we do. I'm only showing that our words can, and do, refer to these beetles.

In a situation like the below, both may agree with the proposition "the strawberry is foo-coloured", and may even agree that the word "foo" (sometimes) refers to a disposition to reflect a particular wavelength of light, but I think it unproblematic to accept that the word "foo" also refers to the private phenomenal character of the individual's experience, even if neither can know the other's. If someone were to secretly surgically alter their eyes and/or brains such that the phenomenal character was mirrored then each would say "the strawberry is no longer foo-coloured", and then be very confused when they measure the wavelength of light and detect no change. — Michael

I feel like this example changes the grammar rules. Initially, we relied upon X to determine the word's usage, and then we changed to Y. When it was X, we relied upon our internal impression of the entity to use the word "foo" and then when it was Y, we relied upon our internal impression of wavelength measuring device to use the word "foo." That means our words have changed meaning, which is an interegral part of any word game, which is the ability of the players of the game to make and change rules.

The point here is not that there is not reliance upon perception when we speak, the issue is the relevance of what the perception is and whether it is similar across people. It is not. My beetle and your beetle may or may not be the same thing. It doesn't matter.

The point is to stop trying to do metaphysics and figure out what's going on in your head because that is beyond the scope of philosophy.

All of this is presented as implicitly rejecting the idea that meanings are fixed by hidden reference-makers (phenomenal or physical), and treating meaning instead as constituted by the public criteria governing a word’s use within a practice. That is, there are in fact all sorts of internal things going on in your mind that may in fact be the cause of your utterances, but we don't fix meaning by those, but we fix it by usage. Your example makes that clear, showing that regardless of the internal causes, even when they are dissimilar across speakers, the language game makes sense upon relieance upon usage without worrying about the internal causes. -

Hanover

15.3kI think an important point to mention when we say "meaning is use" is that it completely disentangles metaphysics from grammar. Grammar answers the question of how we use words. When I say "I see a ship" and you ask what is a "ship," under a meaning is use analysis, the "ship" is defined by how it is used. If you start asking about the atomic structure of the ship and how the photons bounce off the boards to your optic nerve, you are answering a very different question.

Hanover

15.3kI think an important point to mention when we say "meaning is use" is that it completely disentangles metaphysics from grammar. Grammar answers the question of how we use words. When I say "I see a ship" and you ask what is a "ship," under a meaning is use analysis, the "ship" is defined by how it is used. If you start asking about the atomic structure of the ship and how the photons bounce off the boards to your optic nerve, you are answering a very different question. -

Michael

16.9kAll of this is presented as implicitly rejecting the idea that meanings are fixed by hidden reference-makers (phenomenal or physical), and treating meaning instead as constituted by the public criteria governing a word’s use within a practice. That is, there are in fact all sorts of internal things going on in your mind that may in fact be the cause of your utterances, but we don't fix meaning by those, but we fix it by usage. Your example makes that clear, showing that regardless of the internal causes, even when they are dissimilar across speakers, the language game makes sense upon relieance upon usage without worrying about the internal causes. — Hanover

Michael

16.9kAll of this is presented as implicitly rejecting the idea that meanings are fixed by hidden reference-makers (phenomenal or physical), and treating meaning instead as constituted by the public criteria governing a word’s use within a practice. That is, there are in fact all sorts of internal things going on in your mind that may in fact be the cause of your utterances, but we don't fix meaning by those, but we fix it by usage. Your example makes that clear, showing that regardless of the internal causes, even when they are dissimilar across speakers, the language game makes sense upon relieance upon usage without worrying about the internal causes. — Hanover

And yet the example should show that the usage will change if the phenomenal character of experience changes, even though nothing about the strawberry or the light changes, so clearly the phenomenal character of experience also has something to do with the meaning of the word "foo" in their language.

Although, saying that the usage will change is somewhat ambiguous. It changes in the sense that they no longer describe strawberries as being "foo-coloured", but then that would also be true if rather than a secret surgery on their eyes someone secretly dyed strawberries (and every other "foo-coloured" thing). This will change which things are described as being "foo-coloured" but it doesn't follow that the meaning of the word "foo" has changed.

I think an important point to mention when we say "meaning is use" is that it completely disentangles metaphysics from grammar. Grammar answers the question of how we use words. When I say "I see a ship" and you ask what is a "ship," under a meaning is use analysis, the "ship" is defined by how it is used. If you start asking about the atomic structure of the ship and how the photons bounce off the boards to your optic nerve, you are answering a very different question. — Hanover

I agree that metaphysics and grammar are different things; I just disagree with the claim either that the phenomenal character of experience is not real or that it does not have anything to do with language. It's real, and like every other real (and even unreal) thing in the universe, we can talk about it. -

frank

19kI think an important point to mention when we say "meaning is use" is that it completely disentangles metaphysics from grammar. Grammar answers the question of how we use words. When I say "I see a ship" and you ask what is a "ship," under a meaning is use analysis, the "ship" is defined by how it is used. If you start asking about the atomic structure of the ship and how the photons bounce off the boards to your optic nerve, you are answering a very different question. — Hanover

frank

19kI think an important point to mention when we say "meaning is use" is that it completely disentangles metaphysics from grammar. Grammar answers the question of how we use words. When I say "I see a ship" and you ask what is a "ship," under a meaning is use analysis, the "ship" is defined by how it is used. If you start asking about the atomic structure of the ship and how the photons bounce off the boards to your optic nerve, you are answering a very different question. — Hanover

If by "meaning is use" we're envisioning that some activity is underway, and my language comprehension is entirely dependent on successful collaboration, then we have a kind of stilted scenario. I mean, when you read a history book, there's no collaborative activity that would allow you to feel confident about your interpretation, and yet most people don't struggle with reading.

Much of the time, you understand people because you're (possibly half-consciously) putting yourself in their shoes, looking at the world through their eyes. I think this is how reading works. Discerning context requires a meeting of minds. Now you could argue that such a meeting of minds is just a folk explanation. It doesn't really happen. But if that's true, how exactly does reading work? Kripke shows that it's probably not rule following.

So if the "put yourself in their shoes" scenario is how communication really works, then there is a consideration of what "ship" refers to. You'll need this once you are seeing the world that the speaker sees. -

RussellA

2.7kAll of this is presented as implicitly rejecting the idea that meanings are fixed by hidden reference-makers (phenomenal or physical), and treating meaning instead as constituted by the public criteria governing a word’s use within a practice. — Hanover

RussellA

2.7kAll of this is presented as implicitly rejecting the idea that meanings are fixed by hidden reference-makers (phenomenal or physical), and treating meaning instead as constituted by the public criteria governing a word’s use within a practice. — Hanover

Where is the meaning of a word fixed?

Each individual has five senses. All information about anything external to the individual can only pass through the individual's five senses.

The Direct Realist believes each individual has direct cognition of a public sphere with its public language game. The Direct Realist believes that such a public sphere exists independently of any mind.

The Indirect Realist believes that each individual can only infer such a public sphere by reasoning about experiences perceived in their five senses.

Therefore, for the Direct Realist, meaning is fixed in a public sphere independent of any mind. For the Indirect Realist, meaning is fixed in each individual’s mind by reasoning about experiences perceived in their five senses. -

Esse Quam Videri

444Between the mind and any external world are the five senses. The mind only knows what passes through these five senses. Therefore, for the Indirect Realist, anything we think we know about any external world comes indirectly from “inference to the best explanation”. However, for the Direct Realist, we are able to transcend these five senses and directly know about any external world.

Esse Quam Videri

444Between the mind and any external world are the five senses. The mind only knows what passes through these five senses. Therefore, for the Indirect Realist, anything we think we know about any external world comes indirectly from “inference to the best explanation”. However, for the Direct Realist, we are able to transcend these five senses and directly know about any external world.

One question for believers in SDR is how they explain their judgements are able to transcend their phenomenal experiences — RussellA

I can only speak for myself on this, but I do not reject the idea that knowledge is mediated by the senses. What I reject is the idea that sensory content forms an epistemic base from which the rest of our knowledge about the world is inferred.

The key issue here is that sensation is not a normative act. This means it is not conceptual and is not truth-apt – it is simply not the kind of thing from which the rest of our knowledge could be inferred.

By contrast, judgment is conceptual and truth-apt. The act of judgment is part of the norm-governed process of inquiry. So, while judgments are constrained by sensory content, they are not inferred from sensory content. As we argued above, this would be impossible.

When we make perceptual judgments we are not making judgments about sensory content. We are making judgments about things in the world (“there is a ship”). That’s not to say that we can’t make judgments about sensory content – we can (“I am seeing red”) – but this is not what we ordinarily mean by the word “perception”. Instead, this is a reflexive, second-order kind of judgment more commonly referred to as “introspection”.

I would argue that perceptual judgments are neither inferred from nor justified by introspective judgments. If someone questions one of our perceptual judgments, we don’t try to justify it by appealing to introspective judgments. Instead, we appeal to background knowledge and other perceptual judgments.

Consider the example of John and Jane that provided. Jane makes a perceptual judgment (“the screen is orange”) and infers that the wavelength of the light is between 590nm and 620nm. Appealing to an introspective judgment (“I am seeing orange”) in order to justify her perceptual judgment simply won’t convince anyone, including herself. If she really wants to justify her judgment that the screen is orange, she’ll need to appeal to her background knowledge (optics, screens, color-blindness, etc.) and further perceptual judgments about her environment (current lighting, viewing angle, screen filters, etc.).

So when you ask how judgments are able to “transcend” phenomenal experience, my answer is that they can’t – at least not in the sense of bypassing or overriding the senses, nor by inference from inner representations. Rather, judgments were never justified by phenomenal experience to begin with. Sensory experience constrsins inquiry by supplying data, but epistemic authority belongs to judgment, which is governed by norms of sufficiency, relevance, and answerability to how things actually are. Once that distinction is in view, the need to “bridge” phenomenal experience via IBE largely dissolves. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

That's not a redefinition. What this shows is how you misdiagnose the the argument. In your visor world, the visors drop out of the discussion when folk talk about ships. They are not seeing the image on the screen, they are seeing ship.You're seriously trying to redefine "direct perception" in such a way that even with these visors and their computer-generated images on a screen they still directly see their shared environment? — Michael

Direct realism doesn't claim that direct perception is perception without mediation. That would rule out glasses, mirrors, telescopes, microscopes, hearing aids, telephones — and even eyes and nerves. Mediation is ubiquitous and trivial. What matters is not causal mediation but epistemic termination. This is why your visor world makes no difference. The visor drops out of consideration, much as the beetle in a box does in discussions of private language. The function of the visor is irrelevant, in that the moment you insist — as the indirect realist must — that what we really ever see is only the visor-image, the example collapses.

When you hear your mother on the phone, you do not hear sound waves and then infer your mother as a hypothesis about an inner item. You hear your mother speaking, by means of sound waves, transmission systems, speakers, etc. The fact that you do not experience the causal chain as such is irrelevant — because direct realism never required that.

Direct realism is not the thesis that perception includes awareness of causal links. It is the thesis that perceptual verbs take worldly objects as their logical objects. You hear your mother, not a sound-wave-token; you see the ship, not a retinal image. The mediation is causal, not epistemic.

We can talk about the image on the visor, but this is derivative, dependent on our being able to talk about an image of the ship, and hence being able to talk about the ship.

The argument here is not redefining “direct”; but refusing to accept a Cartesian picture in which perception must either be inner and certain or outer and inferential.

This is were a Markov Blanket helps. On the indirect realist construal, the Markov blanket is treated as epistemically opaque. On the direct realist construal, the blanket is only causally isolating. Information flows across it, but that does not lead to epistemic confinement. The organism’s perceptual capacities are attuned to environmental states across the blanket; perception is an interaction spanning the boundary, not an encounter with an inner surrogate. What is perceived is the ship, not a mental image that stands in for it.

The indirect realist uses the debunked picture of a theatre of consciousness; the homunculus, sitting inside only ever seeing the ship on the visor. The better picture is that we see the ship, using the visor. There is no phenomenal state that is what we see in the place of the ship; rather, the neural process that constructs vision constitutes your seeing the ship. -

Hanover

15.3kBecause at some stage the conversation has a use. — Banno

Hanover

15.3kBecause at some stage the conversation has a use. — Banno

That it has a use doesn't mean it can be had. Wittgenstein is diagnostic. Philosophy is declared incompetent for addressing the metaphysical.

But if you just need an explanation even though you realize it will be fraught with inconsistency and just becauses, posit the gods like I do. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

Not at all sure what that means.That it has a use doesn't mean it can be had. — Hanover

The choice here is between on the one hand an account that divides the world into mind and object, then finds itself unable to explain objects; and an account that makes no such presumption.

One account begins by dividing mind from world and then cannot recover the world. The other refuses that division and never loses it.

Perception is a activity within the world, not an impassible bridge between worlds.

And here's the thing: we do manage to talk about ships, cups, walls and each other. -

Hanover

15.3kI agree that metaphysics and grammar are different things; I just disagree with the claim either that the phenomenal character of experience is not real or that it does not have anything to do with language. It's real, and like every other real (and even unreal) thing in the universe, we can talk about it. — Michael

Hanover

15.3kI agree that metaphysics and grammar are different things; I just disagree with the claim either that the phenomenal character of experience is not real or that it does not have anything to do with language. It's real, and like every other real (and even unreal) thing in the universe, we can talk about it. — Michael

The phenomenonal is absolutely real. My claims have always been grammatical, not ontological. Phenomenonal states are causally related to utterances. If not, I'd be arguing we're p-zombies.

You can talk about "phenomenonal states" just like you can talk about cats and unicorns and kings of France. It is irrelevant whether you have phenomenonal state for you to talk about them.

When you do speak of them, whatever is doing the work is the rule-governed use of the term, not privileged access to a phenomenal state whose identity could float free of that use. -

RussellA

2.7kI can only speak for myself on this, but I do not reject the idea that knowledge is mediated by the senses. — Esse Quam Videri

RussellA

2.7kI can only speak for myself on this, but I do not reject the idea that knowledge is mediated by the senses. — Esse Quam Videri

To my understanding of perception:

Stage one is the mental, introspective, singular, particular phenomenal experience in the senses when the eye is directed at a wavelength of say 630nm. This is neither conceptual nor truth-apt. As you say, it is not a normative act.

The key issue here is that sensation is not a normative act. This means it is not conceptual and is not truth-apt – it is simply not the kind of thing from which the rest of our knowledge could be inferred.@Esse Quam Videri

Stage two is the introspective awareness that “I am seeing orange”. This is conceptual, as “orange” is a concept. This is not truth-apt, and therefore not a judgement, because if I see orange then I see orange. Stage two is not an introspective judgement.

That’s not to say that we can’t make judgments about sensory content – we can (“I am seeing red”) – but this is not what we ordinarily mean by the word “perception”. Instead, this is a reflexive, second-order kind of judgment more commonly referred to as “introspection”.@Esse Quam Videri

Stage three is the introspective judgement that “the screen is orange”. Such a judgement is conceptual, because “screen” is a concept. The judgement is truth-apt on the assumption that there is a mind-external world where there are such things as screens. “The screen” is referring to something mind-external. I agree that introspective judgements about something mind-external are constrained by sensory content, but disagree that they are not inferred from sensory content. How can we get knowledge about any mind-external world if not from our sensations? What other way is there to get knowledge about a mind-external world if not from our sensations?

By contrast, judgment is conceptual and truth-apt. The act of judgment is part of the norm-governed process of inquiry. So, while judgments are constrained by sensory content, they are not inferred from sensory content. As we argued above, this would be impossible.@Esse Quam Videri

The only information we have about any mind-external world is through our five senses. Therefore our perceptual judgement that “the screen is orange” of logical necessity must be based on our sensations. I agree that we are not making any judgement about the sensory content “I am seeing orange”, because no judgement is needed to know that “I am seeing orange”. But we are making judgements about what the sensory content represents, in that we are judging by inference that “I see orange” in the mind represents in a mind-external world “the screen is orange”. We can only make judgements about things in any mind-external world by inferring from sensory content in the mind.

When we make perceptual judgments we are not making judgments about sensory content. We are making judgments about things in the world (“there is a ship”).

I agree that epistemic authority belongs to judgement about how things actually are. Judgement exists in the mind and how things actually are exists in a mind-external world. Between the mind and a mind-external world are the five senses, meaning that if we are to know anything about a mind-external world it is inevitable that the bridge that is our senses must be crossed.

but epistemic authority belongs to judgment, which is governed by norms of sufficiency, relevance, and answerability to how things actually are.@Esse Quam Videri

From what you say, if there is no need to cross the bridge of our senses, this suggests to me that your position is that of Idealism. There are many kinds of Idealism, but fundamentally, Idealism asserts that reality is entirely a mental construct, which is also why you don’t support the realism of either the direct or indirect realist.

Once that distinction is in view, the need to “bridge” phenomenal experience via IBE (inference to the best explanation) largely dissolves.

I’ve also acknowledged that my own view does not count as traditional naïve realism. My point is that it does not count as traditional indirect realism either.@Esse Quam Videri -

Esse Quam Videri

444Thanks for laying this out so carefully — this helps clarify exactly where we disagree.

Esse Quam Videri

444Thanks for laying this out so carefully — this helps clarify exactly where we disagree.

I want to focus on the role you assign to your stage two, since that’s where the inferential claim is doing all of its work.

You characterize stage two (“I am seeing orange”) as conceptual but not truth-apt, and therefore not a judgment. I’m happy to grant that description for the sake of argument. But then I don’t see how stage two can function as the basis of an inference to stage three. Inference requires premises that are truth-apt — something that can be correct or incorrect. If stage two is not truth-apt, it cannot play that role.

So either stage two is truth-apt, in which case it already is a judgment and your staged model collapses, or it is not truth-apt, in which case the claim that stage-three judgments are inferred from it does not follow.

More generally, I don’t deny that all inquiry is mediated by the senses. What I deny is that mediation entails inferential grounding. Sensory experience supplies data that constrains inquiry, but it does not supply premises from which judgments about the world are inferred. The epistemic work is done at the level of judgment itself, not by moving outward from inner representations.

For that reason, rejecting inferential mediation does not amount to Idealism. It does not deny a mind-external world, nor does it deny sensory mediation. It denies only the empiricist assumption that knowledge of the world must be constructed by inference from sensory contents.

So the disagreement isn’t about whether the “bridge of the senses” must be crossed — it’s about what crossing that bridge amounts to: inferential reconstruction from inner items, or norm-governed judgment constrained by experience but not inferentially derived from it. -

Hanover

15.3kNot at all sure what that means. — Banno

Hanover

15.3kNot at all sure what that means. — Banno

It means that just because you find a need to understand the world doesn't mean you can.The choice here is between on the one hand an account that divides the world into mind and object, then finds itself unable to explain objects; and an account that makes no such presumption. — Banno

If reality is a choice, then let's imbue it with purpose. As they say, imagination is the only weapon in the war against reality.

This is to mean, if you can jettison the distinction between mental states and external states on the grounds it makes reality easier to comprehend, regardless of whether it comforts with actuality, then you've made it no less logical to insert other preferences into this mix.

As in, I choose to maintain the dualstic nature and needn't go through the machinations of eliminating what appears an obvious division, but I choose to insert the mystical to maintain that distinction.

And isn't that to a large degree what modern philosophy attempts to do, but to globally disenchant reality? Maybe that enterprise is impossible, which results not in the dissolution of philosophy, but in keeping it to its boundaries. That, I say, is the implication of Wittgenstein.

This is just about category clarification, and I see no reason to seek unification of stand alone systems. -

Michael

16.9kIn your visor world, the visors drop out of the discussion when folk talk about ships. They are not seeing the image on the screen, they are seeing ship. — Banno

Michael

16.9kIn your visor world, the visors drop out of the discussion when folk talk about ships. They are not seeing the image on the screen, they are seeing ship. — Banno

"Seeing" and "talking about" do not mean the same thing. They are seeing the image on the screen and they are seeing the ship and they are talking about the ship.

It simply doesn't matter what "drops out of [their] discussion". If it helps, consider us to be secret observers, e.g. the mad scientists who engineered these people. Their visors do not "drop out of" our discussion. We ought accept that they do not directly see their shared environment.

That's not a redefinition. — Banno

Yes it is. There is no reasonable account under which these people can be said to directly see the ship (as the term "directly" means in the context of the dispute between direct and indirect realism). A scenario like this is exactly what it means so see something indirectly. -

Michael

16.9kConsider the example of John and Jane that ↪Michael provided. Jane makes a perceptual judgment (“the screen is orange”) and infers that the wavelength of the light is between 590nm and 620nm. Appealing to an introspective judgment (“I am seeing orange”) in order to justify her perceptual judgment simply won’t convince anyone, including herself. If she really wants to justify her judgment that the screen is orange, she’ll need to appeal to her background knowledge (optics, screens, color-blindness, etc.) and further perceptual judgments about her environment (current lighting, viewing angle, screen filters, etc.). — Esse Quam Videri

Michael

16.9kConsider the example of John and Jane that ↪Michael provided. Jane makes a perceptual judgment (“the screen is orange”) and infers that the wavelength of the light is between 590nm and 620nm. Appealing to an introspective judgment (“I am seeing orange”) in order to justify her perceptual judgment simply won’t convince anyone, including herself. If she really wants to justify her judgment that the screen is orange, she’ll need to appeal to her background knowledge (optics, screens, color-blindness, etc.) and further perceptual judgments about her environment (current lighting, viewing angle, screen filters, etc.). — Esse Quam Videri

I didn't mean to suggest that the phenomenal character of experience is sufficient to infer mind-independent facts about the environment (although the naive colour realist does suggest this, and is wrong). Obviously if neither John nor Jane know anything about electromagnetic radiation then they wouldn't infer anything about the wavelength of light emitted by the screen.

It doesn't follow from this that they don't infer mind-independent facts about their environment from the phenomenal character of experience. Given their background knowledge of electromagnetic radiation, computer screens, etc., it is then the phenomenal character of experience that allows them to choose between "the screen emits ~700nm light", "the screen emits ~600nm light", etc, with John's and Jane's different inferences being explained by them having different phenomenal experiences. -

Esse Quam Videri

444I agree that background knowledge plays an essential role, and I also agree that differences in phenomenal experience help explain why different hypotheses are entertained or dismissed. Where I still disagree is in treating phenomenal character itself as an inferential input.

Esse Quam Videri

444I agree that background knowledge plays an essential role, and I also agree that differences in phenomenal experience help explain why different hypotheses are entertained or dismissed. Where I still disagree is in treating phenomenal character itself as an inferential input.

Even given background knowledge, phenomenal character is not truth-apt and cannot function as a premise. It does not count for or against a hypothesis in the way evidence does. Rather, it causally constrains inquiry by making certain hypotheses intelligible or salient and others not.

The inferential work is done entirely at the level of judgment, under norms of relevance and sufficiency, drawing on background knowledge and further perceptual judgments. Phenomenal character helps explain why those judgments arise, but it does not justify them or serve as a premise from which they are inferred.

So I don’t deny that phenomenal experience matters in inquiry; I deny that it plays the epistemic role you’re assigning to it. -

Michael

16.9kphenomenal character is not truth-apt and cannot function as a premise — Esse Quam Videri

Michael

16.9kphenomenal character is not truth-apt and cannot function as a premise — Esse Quam Videri

Phenomenal character isn't truth apt but the premise "I am experiencing such-and-such phenomenal character" is, and so this latter proposition can function as a premise. It's exactly how John and Jane come to their respective conclusions.

John

P1. Electromagnetic radiation with such-and-such wavelengths usually cause people to experience such-and-such phenomenal characters

P2. I am experiencing such-and-such (e.g. orange) phenomenal character

C1. Therefore, the screen is probably emitting electromagnetic radiation with such-and-such a wavelength (e.g. 600nm).

Jane

P1. Electromagnetic radiation with such-and-such a wavelengths usually cause people to experience such-and-such phenomenal characters

P2. I am experiencing such-and-such (e.g. red) phenomenal character

C1. Therefore, the screen is probably emitting electromagnetic radiation with such-and-such a wavelength (e.g. 700nm).

Without each P2 each C1 would be a non sequitur, and given that P1 is the same for both John and Jane there would be no explanation for why each C1 is different.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum