-

Wayfarer

26.1kWhy would I dismiss semantics? — Srap Tasmaner

Wayfarer

26.1kWhy would I dismiss semantics? — Srap Tasmaner

Sorry - that's how I read this:

We have meaning, but machines only have syntax. We have language, but other living things have signaling at best. It's tempting to identify the two hierarchies, to say that animals must have only syntax but no meaning.

But I think this is a mistake. — Srap Tasmaner

Never mind, we'll pick it up later. -

Galuchat

809Meaning is produced by categorisation (which presupposes conceptualisation), or it is assigned by interpretation (which presupposes a non-verbal and/or verbal modelling system).

Galuchat

809Meaning is produced by categorisation (which presupposes conceptualisation), or it is assigned by interpretation (which presupposes a non-verbal and/or verbal modelling system).

It is thought that non-verbal modelling systems precede verbal modelling systems in evolutionary terms. Animals have non-verbal modelling systems, human beings have non-verbal and verbal modelling systems.

Verbal modelling systems (i.e., languages) are a set of signs having paradigmatic (class) and syntagmatic (construction) relations (variations in either type of relation varies meaning), hence; language presupposes vocabulary and syntax.

It would be a mistake to suppose that animals do not produce or assign meaning in terms of phenomena simply because they have a non-verbal (as opposed to verbal) modelling system.

It is species-specific categorisation and interpretation which decodes physical information (received through sensory stimulation and/or interoception), producing semantic information. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kActually, the fact that some things are wet and some are not, is sufficient to prove that wetness has essential properties, as so: — Samuel Lacrampe

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kActually, the fact that some things are wet and some are not, is sufficient to prove that wetness has essential properties, as so: — Samuel Lacrampe

The point is. that things are only "wet" because we call them "wet". That constitutes "the fact" that some things are wet, we agree to call them wet. If we didn't call them wet, then there would be no fact that they are wet. If we agree to call certain things wet, this does not prove that wetness has certain essential properties, it proves that we can agree about which things to call wet.

This might get a bit off topic, but I think your claim here is a non-issue, because in real life, there is no such thing as a negative number in the absolute sense. E.g. there is no negative absolute temperature, pressure or mass. So I agree that quantities do not allow for negative values, but this is in conformance to reality. — Samuel Lacrampe

Now it appears like you are starting to see my point. We produce our concepts according to how we perceive reality, not according to some "essential properties". We can name essential properties, according to how we perceive reality, agree on them, and use that as a guide in applying the concept, but this does not mean that any particular word necessarily refers to any particular set of essential properties.

Greenness, the thing in itself, is not this 'range of wavelength of light' you describe. If it were, then it would be logically impossible for us to imagine greenness without imagining a light source, inasmuch as we cannot imagine a triangle without imagining three sides; but we can imagine greenness by itself. The true concept of greenness is not about wavelengths, but is simply this. Rather than being one and the same thing, this 'range of wavelength of light' is a cause of us sensing greenness, or to use Aristotle's terminology, it is an efficient cause of greenness, not its formal cause. — Samuel Lacrampe

This seems to contradict your claim that concepts have essential properties. If we cannot define "greenness", only experience it, then how can it have essential properties? For instance, I often see as green, what others see as blue. According to what you say, I assume that I am correct in calling this green, and the others are correct in calling this blue, because this is how we each experience the colour. How can there be essential properties of greenness when the same colour is correctly called green by me, and blue by others? -

Harry Hindu

5.9kIt's funny to see them ignore our comments, Galuchat, while they continue to go round and round - never getting at what information actually is. Hmmmph. "Philosophers".

Harry Hindu

5.9kIt's funny to see them ignore our comments, Galuchat, while they continue to go round and round - never getting at what information actually is. Hmmmph. "Philosophers". -

Harry Hindu

5.9kAnd they bash certain scientists for being dismissive of philosophy. The hypocrisy!

Harry Hindu

5.9kAnd they bash certain scientists for being dismissive of philosophy. The hypocrisy!

What these extremists in "both camps" don't realize is that philosophy is a science. -

Wayfarer

26.1kIt is species-specific categorisation and interpretation which decodes physical information (received through sensory stimulation and/or interoception), producing semantic information. — Galuchat

Wayfarer

26.1kIt is species-specific categorisation and interpretation which decodes physical information (received through sensory stimulation and/or interoception), producing semantic information. — Galuchat

Very learned post, but it is still the case that no animal can understand the concept of 'prime number' (for instance).

philosophy is a science. — Harry Hindu

The difference between philosophy and science is a philosophical distinction. -

Wayfarer

26.1kt's funny to see them ignore our comments, — Harry Hindu

Wayfarer

26.1kt's funny to see them ignore our comments, — Harry Hindu

Actually, Harry Hindu, the reason I ignored your comments is because of your dismissive attitude - 'the question is nonsense' - and your (I'm sorry to say) obvious lack of understanding of anything beyond pop science. It's not rudeness, but life being too short. -

A Christian Philosophy

1.2k

A Christian Philosophy

1.2k

Unless I misunderstood what you said, I think I agree with you that just because we agree on the meaning of the concept 'wet', it does not follow that the particular thing we observe is in fact wet. It could be a false perception of wetness. But this is besides the point about essential properties. If you and I mean the same thing when using the word 'wet', then the meaning has some essential properties. More explanation further down.The point is. that things are only "wet" because we call them "wet". That constitutes "the fact" that some things are wet, we agree to call them wet. If we didn't call them wet, then there would be no fact that they are wet. If we agree to call certain things wet, this does not prove that wetness has certain essential properties, it proves that we can agree about which things to call wet. — Metaphysician Undercover

But it does. Let's say you and I observe a chair. Assuming no false perceptions are present, you would be confused if I said "This is a lake", and rightfully so. Because the observed things correspond to the properties attributed to a chair, not a lake. Sure, some of the observed properties would be accidental, like its colour and location, but some would be essential like having a backrest or being a structure. And no observed properties would correspond to properties essential to the concept of lake, like 'a large body of water'.[...] but this does not mean that any particular word necessarily refers to any particular set of essential properties. — Metaphysician Undercover

This concept is so basic that it has only one essential property: being green, or this; which does not help. Another reason why 'greenness' was a bad example to prove my point. I should really stick to triangle-ness haha.If we cannot define "greenness", only experience it, then how can it have essential properties? — Metaphysician Undercover

Essential properties are essential to the concept; not necessarily essential to the particular things we observe. We could have false perceptions of the things we are observing. And when you call the thing green and we call it blue, we may disagree on the fact, but we still understand what each other mean by green and blue.According to what you say, I assume that I am correct in calling this green, and the others are correct in calling this blue, because this is how we each experience the colour. How can there be essential properties of greenness when the same colour is correctly called green by me, and blue by others? — Metaphysician Undercover -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kLet's say you and I observe a chair. Assuming no false perceptions are present, you would be confused if I said "This is a lake", and rightfully so. Because the observed things correspond to the properties attributed to a chair, not a lake. Sure, some of the observed properties would be accidental, like its colour and location, but some would be essential like having a backrest or being a structure. And no observed properties would correspond to properties essential to the concept of lake, like 'a large body of water'. — Samuel Lacrampe

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kLet's say you and I observe a chair. Assuming no false perceptions are present, you would be confused if I said "This is a lake", and rightfully so. Because the observed things correspond to the properties attributed to a chair, not a lake. Sure, some of the observed properties would be accidental, like its colour and location, but some would be essential like having a backrest or being a structure. And no observed properties would correspond to properties essential to the concept of lake, like 'a large body of water'. — Samuel Lacrampe

That is what I do not agree with.

If we are calling a certain object by the name of "X", and I can recognize and call that object X, then it does not follow logically that X must have essential features, unless you define "essential features" in some odd way.

Furthermore, if there is a type of object, which we class as "Y", and we can agree to call some objects by the name "Y", and that some objects should not be called Y, this is even less indicative that we should believe that called "Y" have an essential nature.

Do you not recognize, that in both these cases, our agreement to call objects by a specific name, "X", or "Y", says something about our capacity to agree on this type of thing, rather than something about the objects themselves? Both of these premises say something about our ability to agree on how to name something. Unless you put forward a premise which indicates a relationship between this ability to agree, and the actual existence of the object, you cannot make any logical conclusions about the objects themselves.

Now, you claim that there is a concept of "Y". What does "concept" refer to? Does it refer to the individual's capacity to class an object as "Y", or does it refer to the fact that we can agree to call certain objects by "Y", and that other objects should not be called "Y"? In either case, how do you get to the conclusion that the concept itself consists of essential features? The fact that we agree does not necessitate the conclusion of essential features unless you define essential features as what we agree on. -

Harry Hindu

5.9k

Harry Hindu

5.9k

No. You wanted to have a discussion about Jerry Coyne, remember? You wanted to focus on a small sentence that wasn't even that important in my post, remember? And I told you that I'm not being dismissive - that I have done a 180 on my worldview before and that I can do so again if the explanation and answer to my questions are reasonable. You seem to think that I should accept an unreasonable question. You do believe that there are such things as nonsensical questions, don't you? If I said that a question is nonsense, then make an attempt to clarify, or tell me why it's not nonsense. When I've seen you "waste your time" with others who are actually thick-headed, I know that your complaint against me here isn't actually true. You just don't have the answers to the difficult questions that you should be asking yourself.Actually, Harry Hindu, the reason I ignored your comments is because of your dismissive attitude - 'the question is nonsense' - and your (I'm sorry to say) obvious lack of understanding of anything beyond pop science. It's not rudeness, but life being too short. — Wayfarer

What does that even mean? No, I'm not being dismissive. I'm asking a question that, if you have a legitimate, reasonable, answer to, then I can be swayed to see your side of things. So, instead of getting frustrated at difficult questions, that you should be asking yourself, try to answer them because it will do you as much good as it would for me.The difference between philosophy and science is a philosophical distinction. — Wayfarer -

Wayfarer

26.1kThe difference between philosophy and science is a philosophical distinction.

Wayfarer

26.1kThe difference between philosophy and science is a philosophical distinction.

— Wayfarer

What does that even mean? — Harry Hindu

Mainly, it means that philosophy is primarily concerned with a ‘metaphysic of value’ - some factual basis for values and meaning. Science doesn’t provide any such basis, as it is concerned with what is measurable, with objective fact. This is what underlies the ‘is-ought’ distinction that Hume is associated with. -

A Christian Philosophy

1.2k

A Christian Philosophy

1.2k

First let's clarify a few things, just in case there is a misunderstanding with these.

1. Words are not concepts. Words point to concepts. Words are man-made and decided upon; concepts are abstracted. The word 'bird' in english is different than the word 'oiseau' in french, yet they both point to the same concept: the flying beaky thing.

2. Just because I claim that concepts have essential properties, it does not follow that the particular thing we observe necessarily has these essential properties too. We could have false perceptions. E.g. a colourblind may observe a grey chair, and thus have 'greyness' in mind at that moment, but it does not follow that the chair is objectively grey.

Now, I will attempt to break down my previous argument in steps:

1. An property of a concept is called essential if, when it is removed, then the concept is no longer present (not recognizable). Conversely, a property is called accidental if the concept remains after the property is removed. This is easy to see: A triangle in which we remove its three sides is no longer a triangle; therefore 'three sides' is an essential property of triangle-ness. Conversely, a triangle in which we remove its colour remains a triangle; and therefore colour is an accidental property of triangle-ness.

2. The fact is that we recognize a concept in some things X, and not in other things Y.

3. This means that properties of that concept exist in X and not in Y.

4. If all the properties in X were accidental to the concept, then the concept would still be present in Y, as established in step 1; but it is not.

5. Therefore some of the properties found in X are essential properties of the concept. -

Wayfarer

26.1kConsider that when you think about triangularity, as you might when proving a geometrical theorem, it is necessarily perfect triangularity that you are contemplating, not some mere approximation of it. Triangularity as your intellect grasps it is entirely determinate or exact; for example, what you grasp is the notion of a closed plane figure with three perfectly straight sides, rather than that of something which may or may not have straight sides or which may or may not be closed. Of course, your mental image of a triangle might not be exact, but rather indeterminate and fuzzy. But to grasp something with the intellect is not the same as to form a mental image of it. For any mental image of a triangle is necessarily going to be of an isosceles triangle specifically, or of a scalene one, or an equilateral one; but the concept of triangularity that your intellect grasps applies to all triangles alike. Any mental image of a triangle is going to have certain features, such as a particular color, that are no part of the concept of triangularity in general. A mental image is something private and subjective, while the concept of triangularity is objective and grasped by many minds at once. And so forth. In general, to grasp a concept is simply not the same thing as having a mental image.

Wayfarer

26.1kConsider that when you think about triangularity, as you might when proving a geometrical theorem, it is necessarily perfect triangularity that you are contemplating, not some mere approximation of it. Triangularity as your intellect grasps it is entirely determinate or exact; for example, what you grasp is the notion of a closed plane figure with three perfectly straight sides, rather than that of something which may or may not have straight sides or which may or may not be closed. Of course, your mental image of a triangle might not be exact, but rather indeterminate and fuzzy. But to grasp something with the intellect is not the same as to form a mental image of it. For any mental image of a triangle is necessarily going to be of an isosceles triangle specifically, or of a scalene one, or an equilateral one; but the concept of triangularity that your intellect grasps applies to all triangles alike. Any mental image of a triangle is going to have certain features, such as a particular color, that are no part of the concept of triangularity in general. A mental image is something private and subjective, while the concept of triangularity is objective and grasped by many minds at once. And so forth. In general, to grasp a concept is simply not the same thing as having a mental image.

Now the thought you are having about triangularity when you grasp it must be as determinate or exact as triangularity itself, otherwise it just wouldn’t be a thought about triangularity in the first place, but only a thought about some approximation of triangularity. Yet material things are never determinate or exact in this way. Any material triangle, for example, is always only ever an approximation of perfect triangularity (since it is bound to have sides that are less than perfectly straight, etc., even if this is undetectable to the naked eye). And in general, material symbols and representations are inherently always to some extent vague, ambiguous, or otherwise inexact, susceptible of various alternative interpretations. It follows, then, that any thought you might have about triangularity is not something material; in particular, it is not some process occurring in the brain. And what goes for triangularity goes for any thought that involves the grasp of a universal, since universals in general (or at least very many of them, in case someone should wish to dispute this) are determinate and exact in a way material objects and processes cannot be. — Edward Feser

Some brief arguments for dualism part IV -

Wayfarer

26.1kAlso, from the same blog post:

Wayfarer

26.1kAlso, from the same blog post:

For Plato, Aristotle, Aquinas, and other ancients and medievals, the main reason why the mind has to be immaterial concerns its affinity to its primary objects of knowledge, namely universals, which are themselves immaterial. When properly fleshed out and understood, this sort of argument is in my view decisive.

Also my view. Unfortunately, I've been born in the wrong century. (Although I do admit, it has its good points.) -

Wayfarer

26.1kI see your point. What I took from it is this: that the concept 'triangularity' is determinate and exact, i.e. if I asked you to 'draw a triangle', then you would have to draw a figure comprising three straight lines on a plane enclosing a space. But it wouldn't matter whether you drew it with a pencil, or spelled it out on the landscape with rune-stones. Or any other media. Whereas if you drew a four-sided figure, or a figure with curved lines, or not on a plane, then none of those would be a triangle. (This is where the example is relevant to the thought-experiment in the OP.)

Wayfarer

26.1kI see your point. What I took from it is this: that the concept 'triangularity' is determinate and exact, i.e. if I asked you to 'draw a triangle', then you would have to draw a figure comprising three straight lines on a plane enclosing a space. But it wouldn't matter whether you drew it with a pencil, or spelled it out on the landscape with rune-stones. Or any other media. Whereas if you drew a four-sided figure, or a figure with curved lines, or not on a plane, then none of those would be a triangle. (This is where the example is relevant to the thought-experiment in the OP.)

I agree that what he says about the sense in which a drawn triangle not being 'the ideal triangle' is awkwardly put. It's not as if a drawn triangle simply can't match the ethereal perfection of the Ideal Triangle - it's more that, the idea of triangle is such that it can many completely diverse forms, and still be a triangle and nothing else. The triangle is, I think, a simple example of the Platonic eidos.

He gives another example elsewhere using a figure called a chilliagon, which is a bounded geometric object comprising 1,000 sides. To the naked eye, at first glance, it looks damn like a circle - but it isn't a circle, it's a chilliagon. If you were asked to draw such a figure, you might find it a very difficult thing to do, but you would have to produce a thousand-sided figure, not a circle - because you would understand the concept. -

Harry Hindu

5.9k

Harry Hindu

5.9k

How do you go about determining the factual basis for values and meaning without measurements of values and meaning?Mainly, it means that philosophy is primarily concerned with a ‘metaphysic of value’ - some factual basis for values and meaning. Science doesn’t provide any such basis, as it is concerned with what is measurable, with objective fact. This is what underlies the ‘is-ought’ distinction that Hume is associated with. — Wayfarer

It seems to me that you are concerned with objective facts as you are attempting to make objective statements about values and meaning. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kWords point to concepts. Words are man-made and decided upon; concepts are abstracted. — Samuel Lacrampe

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kWords point to concepts. Words are man-made and decided upon; concepts are abstracted. — Samuel Lacrampe

Abstracted things are artificial, and decided upon too. What else, other than a human mind would perform the act of abstraction, and whether the abstraction is correct or not, is decided upon by the human mind as well.

2. The fact is that we recognize a concept in some things X, and not in other things Y.

3. This means that properties of that concept exist in X and not in Y.

4. If all the properties in X were accidental to the concept, then the concept would still be present in Y, — Samuel Lacrampe

I don't get this at all. We do not recognize a concept within things. The concept is within the mind, and when we apprehend a thing as meeting the conditions of the concept, we feel justified in calling the thing by the name which corresponds to that concept. Conversely, when we create concepts, we often try to formulate the concepts so as to best represent the thing which is being referred to by the corresponding word. There is no instances of the concept existing within the thing, as the concept is always within the mind.

He gives another example elsewhere using a figure called a chilliagon, which is a bounded geometric object comprising 1,000 sides. To the naked eye, at first glance, it looks damn like a circle - but it isn't a circle, it's a chilliagon. If you were asked to draw such a figure, you might find it a very difficult thing to do, but you would have to produce a thousand-sided figure, not a circle - because you would understand the concept. — Wayfarer

That a universal concept, such as triangle, exists by definition, (i.e., the existence of the concept of triangle is dependent on the definition of triangle), does not provide an argument that the concept is not dependent on "some process occurring in the brain". Any definition requires interpretation, and this is done by a brain. What is non-physical, is the content within the brain, which the brain is using, in the process of interpretation, the thoughts, and ideas, which are used for interpretation. This appears to produce an infinite regress, because some non-physical thoughts are required to interpret physical definitions etc.. But it need not lead to infinite regress if we accept that the non-physical, which is prior to, and necessary for the physical brain activity of interpretation, is something other than concepts. Then we allow, as Aquinas does, that human concepts are inherently tied to bodily existence, without negating the non-physical existence which is necessary for the existence of concepts. -

charleton

1.2kI do not think there is anything wrong with the idea that every thing is physical. But you cannot necessarily understand it by examining its physical structures. As you cannot understand the story in a book with an analysis of the paper and ink, you cannot examine the knowledge and capabilities of a person with a brain scan.

charleton

1.2kI do not think there is anything wrong with the idea that every thing is physical. But you cannot necessarily understand it by examining its physical structures. As you cannot understand the story in a book with an analysis of the paper and ink, you cannot examine the knowledge and capabilities of a person with a brain scan.

Yet burn the book and the information is lost, kill the brain and the knowledge goes too. This being the case - a concept is constituted by neural matter, and you can prove it easily enough. -

charleton

1.2kWords are not concepts. True. But a one concept is not another concept.

charleton

1.2kWords are not concepts. True. But a one concept is not another concept.

When I think "bird", it carries a unique set of bird experiences and observations and cannot be the same as yours. Such concepts have to the unique to the matter which comprises them in the neural tissues. Whilst we can agree upon what is and is not a "bird", our concepts can never be directly compared and can only be approximately similar, never the same. -

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

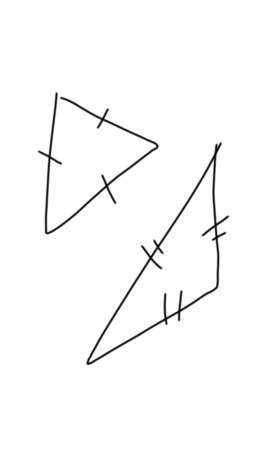

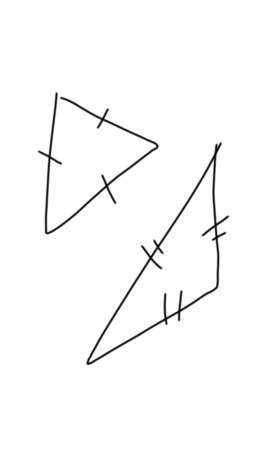

If I ask you to draw a house, I'm asking you to draw a picture of a house. (Only Harold can draw an actual house.)

If you draw a triangle, are you actually drawing a picture of a triangle? No. Here are two equilateral triangles:

When you draw a triangle, you're not really drawing a picture, i.e., a picture of some object that happens to be immaterial. What you're drawing is a diagram, a graphical presentation of your knowledge. And this knowledge is primarily procedural, starting with the definition of "triangle", which is after all stipulative.

You can describe it as knowledge of an abstract object if you like, but what really matters here is knowing how to proceed. The triangles above have equal sides because I say they do. You can say this is a property of these triangles, but the point is that in using these triangles you know to treat their sides as equal. That stipulation gives you a rule to follow. -

Wayfarer

26.1kYou can describe it as knowledge of an abstract object if you like, but what really matters here is knowing how to proceed. — Srap Tasmaner

Wayfarer

26.1kYou can describe it as knowledge of an abstract object if you like, but what really matters here is knowing how to proceed. — Srap Tasmaner

That doesn't add anything to the point; you know how to proceed, because you grasp the idea. Feser makes the same point - that a concept is not a mental image nor a drawing.

That stipulation gives you a rule to follow. — Srap Tasmaner

Such rules are, arguably, a form of universal; they are in one sense, mind-independent, i.e. they're not simply 'in the mind' or dependent on my say-so, but at the same time, they can only be grasped by a rational intelligence; hence, by analogy, they're called 'intelligible objects'. So, my argument is that such ideas are 'real but not physical' - which is very close to the classical idea of them, that Feser is arguing for. -

Janus

17.9kThat doesn't add anything to the point; you know how to proceed, because you grasp the idea. — Wayfarer

Janus

17.9kThat doesn't add anything to the point; you know how to proceed, because you grasp the idea. — Wayfarer

The point would be that there is no mysterious "grasping of the idea" beyond simply knowing how to proceed. The same applies to going to the shops; you know how to go to the shops, thus you know "how to proceed"; but there is no mysterious grasping of the idea 'how to go to the shops' beyond that. You frustratingly always seem to be trying to put something objective, yet utterly mysterious, in place; which seems to be a performative incoherence that produces reified would-be entities that are simply not needed.

We cannot achieve an account of how the world could be intelligible to us that is given in worldly, objectivist terms, which seems to be what you are trying to do by positing objective abstract entities. I say this is a performative incoherence, because you can never say what those entities are, or what they are like; in the kind of way that it can be said what objects of the senses are or are like.

So ironically, it seems to me, despite your best intentions, you are desiring to objectivize the subjective. I don't say you attempt to do this, because really no attempt is ever actually made by you, on account of it being an impossible contradiction, you simply repeatedly allude to the possibility, or "what has been lost" by us moderns, and so on. -

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

There's all this "grasping" in your approach, as if this explains things. Grasping is what you do to an object. I'm saying there's no immaterial object to immaterially grasp. -

Janus

17.9k

Janus

17.9k

Yes, that's another way of making the same point than the way I took. "Grasping" is a metaphor, and Wayfarer seems to be hypostatizing the metaphor. Really nothing at all can be said about the supposedly immaterial objects we supposedly grasp or how we supposedly grasp them. This puts them out of the domain of philosophy, and into the domain of the poetic imagination. I've been making this point in various contexts and in various ways to Wayfarer over and over; but he always seems to slip away without acknowledging and dealing with what has been said to him. -

Wayfarer

26.1kThere's all this "grasping" in your approach, as if this explains things. — Srap Tasmaner

Wayfarer

26.1kThere's all this "grasping" in your approach, as if this explains things. — Srap Tasmaner

Grasp: comprehend fully.

"the press failed to grasp the significance of what had happened"

synonyms: understand, comprehend, follow, take in, realize, perceive, see, apprehend, assimilate, absorb, make sense of, master, get to the bottom of, penetrate.

As distinct from:

1. seize and hold firmly.

"she grasped the bottle"

synonyms: grip, clutch, clasp, hold, clench, lay hold of;

I have here my dear canine, River, a rescue dog. He's capable of grasping a frisbee between his teeth, but has zero chance of grasping 'the concept of a triangle'.

All due respect, the debate about the reality or otherwise of concepts, laws, numbers, and so on, is one of the central questions of philosophy. I'm not 'slipping away' from anything but if you don't see the significance of it, then there's no point in discussing it.This puts them out of the domain of philosophy, and into the domain of the poetic imagination. — Janus -

Wayfarer

26.1kI still do not get it. — Πετροκότσυφας

Wayfarer

26.1kI still do not get it. — Πετροκότσυφας

One response is that, the idea of science itself presumes that there are regularities and an order of nature, the discovery of which is fundamental to scientific practice. Now you might say that too is just 'rooted in human practice', but that strikes me as undermining the very principles that are used to frame scientific explanations.

The reason the order of nature, and numbers, and the like, were held as forms of higher truth by the ancients is, I think, because they are 'nearer to the uncreated'. In all ancient thought, Western and Eastern, 'the uncreated' (which may or may not be conceived in theistic terms) was understood to be the source of the manifest (i.e. the created realm, the world, etc). This is because the uncreated was by definition eternal and not subject to change and decay. The Platonic distrust of the senses goes back to that intuition in which 'the sensory domain', i.e. the world of sense, was transitory and subject to decay. Whereas the principles that underlay the ever-changing phenomena of the world, were their logoi, the reasons why they existed. Numbers and geometric forms, were regarded as being higher than material objects, because less prone to change and decay; they do not come into and go out of existence and are therefore more like the uncreated, than the individual things that constantly arise and perish.

It was that understanding that actually gave rise to science itself. Now, however, science is busily eating its own foundations.

That I get is that because universals are "exact" and not "messy" like their instantiations they're somehow thoughts unlike others, they're "not some process occurring in the brain". — Πετροκότσυφας

We're not able to infer the meaning of anything 'in the brain' from the examination of neural data without deploying the very abilities which you are presuming to try and explain. If you look at some brain-scan and say 'this is what it means', then immediately you are relying on rational inference, the 'laws of thought', 'it means this', 'it doesn't mean that', and so on. The rational underpinnings of science which constantly utilise those laws, go back, as you well know, to Pythagoras, the Platonists, Aristotle, and so on; the idea that these can now simply be explained in terms of neural architecture and adaptive necessity is question begging of a high-degree i.e. it assumes what it sets out to prove. 1 -

Janus

17.9kAll due respect, the debate about the reality or otherwise of concepts, laws, numbers, and so on, is one of the central questions of philosophy. I'm not 'slipping away' from anything but if you don't see the significance of it, then there's no point in discussing it. — Wayfarer

Janus

17.9kAll due respect, the debate about the reality or otherwise of concepts, laws, numbers, and so on, is one of the central questions of philosophy. I'm not 'slipping away' from anything but if you don't see the significance of it, then there's no point in discussing it. — Wayfarer

Can you name a philosopher or two for whom this is a "central question"? What could it mean to say that concepts, laws and numbers are or are not real? How could we go about confirming any answer to the question? Is it possible that the whole question is merely a matter of interpretation of the term 'real'? These are the kinds of questions you need to address, as I see it, otherwise you are indeed "slipping away". -

Wayfarer

26.1kRegularity" is turned into a being itself, when it's an abstraction of our own making, born out out of particulars. In Robinson's words: — Πετροκότσυφας

Wayfarer

26.1kRegularity" is turned into a being itself, when it's an abstraction of our own making, born out out of particulars. In Robinson's words: — Πετροκότσυφας

You don't have to declare that regularities or natural laws 'are beings'. All that is necessary to say, is that what is described as 'lawful regularities' can be used to predict how the phenomena that are subject to them will behave. That is the meaning of the term 'natural law'. Robinson questions whether the term 'law' or even 'natural law' is appropriate, or whether it's anthropocentric, but I simply don't see how there can be any debate that there are such laws. Otherwise, why science at all? How do we make any abstractions, or predictions? They can't be purely arbitrary, they have to be predictive with respect to phenomena. Robinson seems to be saying that they're entirely ‘internal’ to human minds, but they have enabled humans to discover things unknowable by other means. Even in ancient times, they enabled discovery of fundamental principles like leverage and displacement. They're predictive, not simply conventional or arbitrary; emphatically not ‘human inventions’. Having discovered leverage, then you can invent all kinds of things with it; but the principle is not an invention.

I think that, for example, that the Pythagorean theorem describes something that is real whether or not perceived by humans. However it is is something that can only be grasped by a rational intelligence. So that is an example of an 'intelligible principle', i.e. something which is expressible in terms of a mathematical formulae; but that feature is not 'created by humans', only the notation is a human creation. But, nevertheless, it can only be known to a creature sufficiently rational to understand the principle ; hence it is an 'intelligible principle' - real but not physical.

Your cited text seems to make a distinction between thoughts of universals (i.e. triangularity) and other (common?) thoughts, where the former does not occur in the brain. — Πετροκότσυφας

I don't think it says anywhere that 'it doesn't occur in the brain'. What it says, is that the concept of the triangle is essentially rational and not the same as its physical representation. So the fact that one has to 'have a brain' in order to grasp 'the concept of a triangle' is not in dispute; what i would dispute is that such concepts can be meaningfully discussed in terms of 'brain activity', unless, of course, you are a neurobiologist with a professional interest in neural functionality.

Can you name a philosopher or two for whom this is a "central question"? — Janus

Sure, it's a central question in metaphysics, generally. For the last two years, I've been wanting to enroll in an external course at Oxford, Reality, Being and Existence (next enrollment is Jan next year, and I will try again, now I've noticed it). But it focusses on five questions, the last of which is 'Does reality contain universal features as well as particular entities?' - which is a re-statement of the 'realism vs nominalism' debate that is central to this topic.

The book for the course is Crane, Tim, & Farkas, Katalin, (Editors), Metaphysics: A Guide and Anthology (OUP, Oxford, 2004)

Ed Feser, who I referred to above, is a representative of what he describes as the 'Aristotelean-Thomist tradition' and is a realist with respect to universals.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum