-

Banno

30.6kThis is excellent:

Banno

30.6kThis is excellent:

1. Event B occurs.

2. When event A occurs event B follows.

3. Therefore, event A occured before B. — Magnus Anderson

This is a transcendental argument. See https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/transcendental-arguments/

They need to be treated with great caution; they are a source of much philosophical slight-of-hand. -

Banno

30.6kWell, we might try the following...

Banno

30.6kWell, we might try the following...

If we are going to use B to justify A, then we ought be more confident in B than in A. It would be odd to attempt a justification with evidence that was weaker than what is being justified.

It seems odd, then, to back up one's belief that the chooks will lay eggs tomorrow with a vast, profound theory of pragmatism. -

Magnus Anderson

393If we are going to use B to justify A, then we ought be more confident in B than in A. It would be odd to attempt a justification with evidence that was weaker than what is being justified. — Banno

Magnus Anderson

393If we are going to use B to justify A, then we ought be more confident in B than in A. It would be odd to attempt a justification with evidence that was weaker than what is being justified. — Banno

Side-question. I do not come from a philosophical background. I might be interested in philosophical problems and I might be willing to try to solve them on my own but I did not study and I generally do not read philosophy. So I do not understand many of the things that a lot of people on this board take for granted. For example, I don't really know what justification is. Everyone is talking about, and everyone is asking how, to justify this belief or to justify that belief; everyone has certain kinds of philosophical problems that they want others to solve for them or that they themselves want to solve or have solved. But most of these philosophical problems are alien to me. I do not understand what exactly is problematic. So I have to ask, unfortunately, and I believe that by doing so I will remain within the boundaries of the topic, what exactly is justification? I can make my own guesses. For example, it is perfectly sensible, based on how we use the word otherwise, to assume that to justify your beliefs means to try to convince someone else to accept them. And in order to do so, you have to do whatever is necessary for the other person to accept your beliefs. That's a very simple, very general, understanding of what it means to justify a belief. But then, some guy named Plato comes along and says that knowledge is "justified true belief" without ever explaining to whom a belief should be justified. To ourselves? But what does it mean to justify our beliefs to ourselves? Very vague term. In reality, we don't justify our beliefs to ourselves, we simply accept them and when we decide to do so we revise them. What is justification in this context? Making sure that we feel that our beliefs are good enough in order to act upon them? -

Banno

30.6kX-)

Banno

30.6kX-)

Nothing in philosophy is simple. To the detriment of philosophy. There are thousands of books and articles on justification, and whatever i say here will excite objection.

Short answer is that a statement is justified if it can be made to fit in with your other beliefs.

So to know something it must be true, believed and cohere with some ill defined number of our other beliefs.

But that's not the whole story... -

Wayfarer

26.1kSo the surprise - the disproof of an inductive metaphysics - would be if your pissed-away bottle of red magically reconstituted again itself each night, like a Magic Pudding. — apokrisis

Wayfarer

26.1kSo the surprise - the disproof of an inductive metaphysics - would be if your pissed-away bottle of red magically reconstituted again itself each night, like a Magic Pudding. — apokrisis

There was an Irishman who found a lamp that had a genie in it, in an Old Wares store. He was polishing the lamp when the genie appeared. 'Make a wish', she said. 'You get three.' 'Great', he said, 'I love red wine. Give me a bottle of it, that magically reconstitutes itself when emptied'. Shazam! There it was. He chugged the entire contents. 'Wonderful', he says (hiccup.) The genie says 'so what about your other wishes?' 'Two more thanks love!' X-) -

apokrisis

7.8k...the first question, which is "how can we hope to have certain knowledge?", will remain unanswered. I think the first question makes no sense at all. — Magnus Anderson

apokrisis

7.8k...the first question, which is "how can we hope to have certain knowledge?", will remain unanswered. I think the first question makes no sense at all. — Magnus Anderson

The answer would be that we can't have any kind of absolute truth or certainty. So it is a question that was answered. That clears the field to get on with a pragmatic approach to truth and certainty.

Well, there is still then tautological, deductive or Platonic truth. Folk will want to say deductive logic is at least truth-preserving when the syntax is valid. It maps one state of affairs to another without loss of semantics. We could have a debate about that.

And then there is the allied thing of mathematical truths - the things we say about abstract objects like triangles. We can know those things for sure, in a necessary fashion. Again, we could have a debate about that too.

So in a general way, the absolutism is long dead. Pragmatism rules. But at the fringes, people still want to maintain some kind of unquestionable certainty.

So abduction, if I understand you correctly, is a pattern of no-pattern of thinking. You say that it is the least formalisable pattern of thinking which suggests to me that it lacks pattern to a considerable degree. Or it could be that the pattern is complex and thus difficult to understand and formalise? Which one of the two is the case? I am inclined to think the former but I like to keep my options open. — Magnus Anderson

Not really. I was emphasising how we know it is an important part of successful thinking, and yet we are not sure if we can formalise it. We would certainly like to if we can. One of Peirce's many foundational contributions to logic was to bring the issue out into the clear light of day. I argued that he was less successful at given a proper answer.

My own thinking is informed by modern science and its efforts to build pattern recognising machines, as well as the efforts to understand the same in human brains.

Why do Fourier transforms work so well in signal processing, for example? Why do generative neural networks seem a powerful approach? We do have some mathematical models to consider now.

So if abduction is a process of thinking that has very little pattern within itself, this means that abduction is mostly a random process. It's basically random guessing. — Magnus Anderson

Well if that were so, we would hardly ever arrive at a useful hypothesis. It would take us a lifetime to answer a single question in any ordinary IQ test. It is just a simple fact that we can leap towards the explanations which erase the most information and leave us with the core principle we need to follow.

Our brains do it all the time. The question becomes, how? It certainly ain't a serial search process. It certainly doesn't rely on random exploration. There is something gestalt and holistic in how we can feel the edge of an answer and then watch it flesh itself out into a fully fledged aha!

So the brain is doing something in information processing terms - unless you believe that all such mental activity is connected with divine powers.

If you see a disembodied head lying on the floor you are not going to assume "someone clapped his heads and this head popped out of nowhere" you are going to assume something like "someone's head has been cut off". That betrays order. Not necessarily in reality but in thought. — Magnus Anderson

Yep. So inference to the best explanation.

And what should be noted is that we can imagine a gazillion reasons for there being a disembodied head lying on the floor. Maybe a dinosaur bit it off. Maybe that dinosaur was a pterodactyl or a t-rex. The possibilities are endless.

But no. If we are actually any good at this business of reasoning, we will discard a gazillion possibilities pretty much instantly. We will come up with some maximally plausible guess. We will use all the information to hand and assign some Bayesian process of evaluation that leaves some central body of possibility as whatever is the hypothesis that can't be so easily eliminated.

Even Sherlock Holmes knew that. He was the master of abductive logic after all - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sherlock_Holmes#Holmesian_deduction

Abduction has the following form:

1. Event B occurs.

2. When event A occurs event B follows.

3. Therefore, event A occured before B. — Magnus Anderson

Well yes, Peirce did notice that the same terms employed by the classical versions of deductive and inductive arguments could be used to generate a third kind of argument.

So an abductive argument was already contained within the standard formalism. It followed on directly from the truth of those other two. It was there implicit and waiting to be recognised.

That should be a pretty striking fact I would have thought.

If you aren't interested in either induction or deduction, then you won't care about abduction either. But if you do care about those two things, then you have to care about the fact that the same elements just automatically then have a third combination.

-

apokrisis

7.8kIt seems odd, then, to back up one's belief that the chooks will lay eggs tomorrow with a vast, profound theory of pragmatism. — Banno

apokrisis

7.8kIt seems odd, then, to back up one's belief that the chooks will lay eggs tomorrow with a vast, profound theory of pragmatism. — Banno

What's odd is that you want to waste all your time on a philosophy site ranting against critical thinking.

But I'm guessing you suddenly have a lot of time to waste for some reason. -

Rich

3.2kAnd yet it is true that this sentence is in English. We can be certain of it. — Banno

Rich

3.2kAnd yet it is true that this sentence is in English. We can be certain of it. — Banno

Rather than being certain, we can say that those who know English have agreed upon this grammar and syntax as being English. It is helpful to understand this, because what are called "facts" are simply an agreement and consensus within a given population. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI don't really know what justification is. Everyone is talking about, and everyone is asking how, to justify this belief or to justify that belief; everyone has certain kinds of philosophical problems that they want others to solve for them or that they themselves want to solve or have solved. But most of these philosophical problems are alien to me. I do not understand what exactly is problematic. So I have to ask, unfortunately, and I believe that by doing so I will remain within the boundaries of the topic, what exactly is justification? — Magnus Anderson

Wayfarer

26.1kI don't really know what justification is. Everyone is talking about, and everyone is asking how, to justify this belief or to justify that belief; everyone has certain kinds of philosophical problems that they want others to solve for them or that they themselves want to solve or have solved. But most of these philosophical problems are alien to me. I do not understand what exactly is problematic. So I have to ask, unfortunately, and I believe that by doing so I will remain within the boundaries of the topic, what exactly is justification? — Magnus Anderson

In relation to David Hume, the answer was developed in great detail in his book, A Treatise Concerning Human Understanding. I did study that formally, under David Stove. His main premise is like that of the other British Empiricists - that all knowledge is acquired by the senses. Hume had applied the empirical method in order to find an explanation for the way in which ideas are formed. Like other empiricists he assumed that all ideas are derived from sense impressions, but on the basis of this assumption he went beyond the work of his predecessors and denied the possibility of any genuine knowledge of anything that transcends what is supplied by the senses. This has radical consequences when you really think it through - as Hume did. So he denied that we can have real knowledge of an external world - recall in this regard, that Berkeley was also categorised as an empiricist - or of a material or spiritual substance, a self, or of God. While it was clear enough that one may believe in the reality of any or all of these objects, it was pointed out that there is no logical ground for these beliefs nor for the existence of the objects to which they refer.

The truths of logic are certain because they're implied in their premises, i.e. they do no more than re-state in the conclusion that which is present in the premises. They concern only the relationship of ideas. So this leads to 'Hume's fork' - that all knowledge is either from experience, 'a posteriori' - meaning things we learn from having experienced them ('the sun will rise tomorrow' being based on the experience of it always so doing); or it's 'a priori', with examples being 'all bachelors are unmarried' i.e. if you meet an unmarried man you know deductively (not inductively) that he's a bachelor, without reference to experience.

However, it was Kant who questioned this neat distinction between a priori and a posteriori, by way of the 'synthetic a priori', by which we can learn things that are *not* simply contained in the premises of logical statements. That is one of the main points of his famous book, Critique of Pure Reason. (There's quite a good summary here.)

(A philosopher called Quine wrote a well-known paper in the 1950's which questions the veracity of the distinction between a priori and a posteriori.)

some guy named Plato comes along and says that knowledge is "justified true belief" without ever explaining to whom a belief should be justified. To ourselves? But what does it mean to justify our beliefs to ourselves? — Magnus Anderson

Actually, the discussion of the nature of knowledge in Plato is often inconclusive - various solutions are discussed, but many of them end in aporia, that is, philosophical perplexity. When you really drill down into Platonic epistemology, and the way it was developed over the ensuing centuries, it is a deep topic. Plato set the bar very high for what real knowledge is - recall that Platonism generally distrusts sensory knowledge, on the grounds that the objects of sense are in some way uneal, transitory, perishing etc. Ancient philosophy was a lot more like Eastern contemplative traditions in that respect (although also very different, as Platonism had the emphasis on mathematics and forms, which the East never really cottoned on to.) Right now I'm reading Belief and truth by a classicist called Katja Vogt, which has a really interesting take on the original Platonic dialogues on these questions.

Incidentally in most of the other points I agree with Apokrisis. -

apokrisis

7.8kGiving them a name does not alter their invalidity. — Banno

apokrisis

7.8kGiving them a name does not alter their invalidity. — Banno

Calling them invalid does nothing except highlight that their truth claims hinge on matters of semantics rather than syntax.

It's so funny watching you trying to rescue your metaphysical preferences while pretending not to care about metaphysics. :P

Go on. Tell us about lunch again. -

Rich

3.2kWell someone can look at your facts, and say it ain't so, because consensus had not been formed. Try telling someone who never saw English that it is a fact that it is English, and you'll either get a shrug or asked to prove it. At some point the person may join the consensus but not necessarily so. For that person it remains something you just say. The "fact" is only a fact among those who agree it's is.

Rich

3.2kWell someone can look at your facts, and say it ain't so, because consensus had not been formed. Try telling someone who never saw English that it is a fact that it is English, and you'll either get a shrug or asked to prove it. At some point the person may join the consensus but not necessarily so. For that person it remains something you just say. The "fact" is only a fact among those who agree it's is. -

apokrisis

7.8kHmm. Again it is baffling that you sound like you believe this is some kind of devastating criticism.

apokrisis

7.8kHmm. Again it is baffling that you sound like you believe this is some kind of devastating criticism.

Abduction finds the assumptions from which conclusions can be drawn. Deduction finds the conclusions that can be drawn from those assumptions. Inductions then confirm that the conclusions support those assumptions in terms of the predicted facts.

Deduction might be semantics preserving in being syntactically closed, but it can’t generate new information. Whereas abductive inference and inductive inference are both probabilistic in spirit and can go beyond the evidence in ampliative fashion.

As I said, abduction does seem a work in progress. It is hard to boil down its holism into some more reductionist formalism.

But another way to get at it is as retroduction.

We can say the particular fact, A, is observed. And if the general fact, B, were true, then A would be so as a matter of course. Hence, there is reason to suspect that B is true.

So it runs deduction backwards from a conclusion to a likely assumption. And it should make you think a bit about why deduction is only secure in going from the general to the particular, while going from the particular to the general is inductive - that is, going beyond the evidence by a willingness to believe a high probability is good enough to be a workable certainty.

Isn’t that just what you always want when faced by these pesky doubters?

But I agree. Once you get into this business of abduction and the full pragmatist story of how we formulate knowledge, you start to see the much larger scope of the project.

Generality must be fleshed out with some kind of best fit principle. And this is the approach familiar in a philosophy of science understanding of the framing of natural laws. We want the generalisation that discards the most information. And that is in fact a balancing act - a best systems account (BSA) that opposes simplicity and strength.

So there you have a link to Ramsey, Lewis, and the like. Abduction can be bolstered by this same principle.

Likewise the principle of indifference is critical to finding a pragmatic grounding to the particular. There are always going to be an unlimited number of potential differences. But at some point - dictated by a purpose - any further differences will cease to make a difference. And we can see how this applies to the inductive confirmation.

So we need cut offs for the general, and cut offs for the particular. When those are supplied, a process of reasoned inquiry can become self-closing in the tales it tells.

Deduction is merely already closed - syntactically. It can’t discover new semantic content.

But deduction sandwiched between abduction and induction has the means to be open enough to learn and create content. Then achieve a satisfactory degree of self-closure. -

unenlightened

10kBut the future is not like the past.

unenlightened

10kBut the future is not like the past.

Yesterday I had a full bottle of red. Now it is only half full.

Supposing that the future is like the past requires quite a selective view. — Banno

Supposing that the future is not like the past requires an equally selective view.

It is, presumably, the same bottle of wine that was full and is now half full?

One way of avoiding confusion here is to pay close attention to tenses. There is in English no fixed distinction between tensed and un-tensed usage. There might have been once, there might be in the future, but in the meantime there is not, and the "meantime" encompasses at least the history of this thread, and however many more posts it takes to establish a change of usage.

That the future has been like the past (only different, for the nit pickers) is not a supposition, but experience. That it will be like the past, is supposition, imagination, projection. -

Perplexed

70Deduction is basically playing with definitions; nothing more. — charleton

Perplexed

70Deduction is basically playing with definitions; nothing more. — charleton

I believe this would depend on your metaphysical assumptions. It sounds like you are taking a nominalist position which would reduce deduction to the abstract rules of description. If one were to take a more "realist" position with regard to concepts then the information derived from deductive analysis could have ontological validity.

Don't buy into this free will clap trap, as this flies in the face of the massive advances in science of the last 250 years which assert determinism. — charleton

Does this mean that you believe free will to be incompatible with determinism? Would you then say that our sense of free will is an illusion? -

Janus

17.9k

Janus

17.9k

We experience them and understand them as being established invariances. This means that within our cumulative and collective experience they are invariant. What kind of "valid insight" into them beyond that do you imagine we could have? -

SophistiCat

2.4kReductive explanation is a reason to believe. It is the standard reason we believe in everything else, that we have a reductive explanation for its being the case.

SophistiCat

2.4kReductive explanation is a reason to believe. It is the standard reason we believe in everything else, that we have a reductive explanation for its being the case.

The comment I was disputing was "he is simply saying that the reasoning of science cannot justify them, [the passions]".

My argument was, in what way can the reasoning of science "justify" anything other than by explaining the causal chain of its existence back a few steps? — Pseudonym

You are asking the wrong question. Almost none of our beliefs are justified (in our mind) by science. So if you only accept reductive explanations as justification for beliefs, then you would have to conclude that almost all of our beliefs lack any justification whatsoever - and that cannot be true, because it is part of our usual understanding of the notion of "justified belief" that a large proportion of our beliefs is fairly justified.

I have a passion 'hunger', science can explain exactly what that passion is in physical terms (brain states), why it is there causally (DNA - protein synthesis - neurons development - interaction with the environment), and also why it is there teleologically (evolutionary function of hunger). What additional thing can science provide with regards to the proposition "the sky is blue" that is missing from what science can tell us about passions such as to warrant the distinction made? — Pseudonym

Whether or not I know of some scientific explanation for my feeling of hunger or my perception of the color of the sky is completely irrelevant to my warrant for holding the respective beliefs. -

Hanover

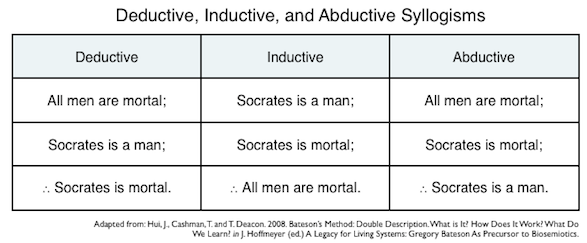

15.2kNeat diagram.

Hanover

15.2kNeat diagram.

Notice that the syllogisms under Inductive and Abductive are invalid?

Giving them a name does not alter their invalidity. — Banno

I'd submit that not only are the conclusions under Inductive and Abductive invalid, but that the chart defining inductive and abductive is invalid. That is it say, inductive logic does not lead one to the conclusion that since Socrates is a man who is mortal that all men must be mortal. Inductive reasoning does not mandate anything, but simply suggests that which is more likely. It would not be a reasonable inductive conclusion to suggest that from a single instance we can draw any likely conclusion either. But, should we observe millions of men all of whom are mortal and should we never observe one who is not mortal, it is entirely reasonable to conclude that all men are likely mortal. Sure, one day a man might emerge who is not mortal, but inductive logic doesn't mandate there will never be an immortal person. Such is no different than any other scientific, empirically based conclusion. We conclude based upon the best evidence we have.

And all of this is apples and oranges anyway because while there may be a limit to what inductive reasoning tells us about the actual world, deductive reasoning tells us nothing about the world. It tells us only about whether truth has been preserved from our premises, yet there is no suggestion (or requirement) that our premises be a truth about the world (e.g. all glurgs are gurps and all gurps are glomps, therefore all glurgs are glomps). So, you can talk about the limitations of inductive reasoning, but the limitations of deductive reasoning are more severe, as it tell us nothing at all other than whether we've correctly solved our Sudoku puzzle. -

charleton

1.2kI believe this would depend on your metaphysical assumptions. It sounds like you are taking a nominalist position which would reduce deduction to the abstract rules of description. — Perplexed

charleton

1.2kI believe this would depend on your metaphysical assumptions. It sounds like you are taking a nominalist position which would reduce deduction to the abstract rules of description. — Perplexed

No. logicians agree that deduction offers no new information, only clarify that which is know. Take the standard syllogism, we already know that Socrates is mortal since he was a man.

Only if you accept that free will is defined as not compelled to act from external forces.Does this mean that you believe free will to be incompatible with determinism? — Perplexed -

SophistiCat

2.4kDoes this mean that you believe free will to be incompatible with determinism? Would you then say that our sense of free will is an illusion? — Perplexed

SophistiCat

2.4kDoes this mean that you believe free will to be incompatible with determinism? Would you then say that our sense of free will is an illusion? — Perplexed

Not that this is particularly relevant to either free will or the actual topic of this thread, but charleton is talking out of his ass: science does not "assert determinism."

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum