-

hunterkf5732

73

hunterkf5732

73

I never said " existence'' couldn't be used as a noun. My contention all along is that, contrary to what you originally said,

(Here I requote)At this point we are talking about the concept of "big", we have made "big" into a noun, to talk about it as a thing, just like the example of "existence" — Metaphysician Undercover — hunterkf5732

"big'' cannot be used as a noun.

An adjective is not a different sot of noun. — Metaphysician Undercover

If we're down to nitpicking, ''sot'' should, in this context, be spelled ''sort''. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kInteresting, I don't generally see it this way, rather I consider the eternal moment, rather than a narrow boundary. — Punshhh

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kInteresting, I don't generally see it this way, rather I consider the eternal moment, rather than a narrow boundary. — Punshhh

Right, but if the moment of the present is to be truly eternal, it cannot partake in either of the two parts of time, future or past. See, we can consider that there is time in the future, and time in the past, but "eternal" means outside of time, so if the moment of the present is to be eternal, it must make a clean division between past and future. I described a slightly different scenario in which the present that we experience consists of partially past, and partially future. The precise division is actually theoretical, such that the concept of a precise, eternal, present, as the division between future and past, is conceptual only, and doesn't adequately represent the reality of time.

However, I still allowed for the eternal (that which transcends temporal existence), by confining temporal existence to the past. Our complete conception of temporal existence, and what it means to exist in time, is based on our experience of the past. This allows that temporal existence comes into being at each moment of the present. The present then is understood under the concept of "becoming". We then have a "prior to temporal existence", which is the other side of the present, and it is what exists on this other side which determines what will come into existence at each moment of the present. This "prior to temporal existence" is where I place the eternal.

That we experience a narrow present due to restrictions imposed on us due to incarnation in the place in which we dwell. The details of our dwelling place I don't take a lot of interest in, as the science to understand it has not been done yet. — Punshhh

I agree that the narrowness of the present which we experience, is due to our physical constitution, and I think that a narrower, or wider present might be experienced by other types of beings. But if you believe that the present has breadth, then doesn't this deny the possibility that the present is an eternal moment, as explained above?

I am not sure of the extent that you consider the momentary generation and dissolution of the objects of sensory experience. Or that they have some kind of longevity?

For me these objects are in a sense eternally present with me in the moment. — Punshhh

I would think that it is necessary to believe that objects do have longevity, but this temporal duration is only in the past. So in a sense, whatever came to be, in the past, is still out there somewhere. It is not evident to us, because of our narrow temporal perspective.

Yes "big" can be used as a noun, when we refer to the concept "big" as if it were a thing. That's the point, it's just not common practise to refer to this concept, as it is common practise to refer to the concept of "existence". Say I am describing the concept of big to you, I can say "big is large". Here, big is the subject (noun), and large is the predicate. If you consider "large" itself, you will see that it is a more common practise to use "large" as a noun, this turns "large" into a thing, a concept, such as when we say "at large", large is a thing, but concept only."...big'' cannot be used as a noun. — hunterkf5732

If you take a word like "red", you will see that it is an adjective used to describe red things, they are red. However, within the conceptual structure it is also a colour. So when we refer to "red" as a colour, red is a noun, because we are using it to refer to the concept of red. -

Punshhh

3.6kThankyou for your input on this, but rather than derail the thread I have started another thread about the eternal moment and would welcome your input. As I would like to explore this further.

Punshhh

3.6kThankyou for your input on this, but rather than derail the thread I have started another thread about the eternal moment and would welcome your input. As I would like to explore this further. -

jorndoe

4.2kTo seek "otherworldly" supernatural explanations, is to extend causation for the occasion.

jorndoe

4.2kTo seek "otherworldly" supernatural explanations, is to extend causation for the occasion.

Causation is temporal, and spacetime is an aspect of the universe, which is how we know causation in the first place.

It would then be natural to ask for sufficient and relevant (non-hypothetical) examples of violations of causal closure, in order to justify such extended causation (no special pleading please). -

jorndoe

4.2kYet another side-track in continuation of some previous comments.

jorndoe

4.2kYet another side-track in continuation of some previous comments.

In the NPR article below, Devinsky (of NYU) mentions the example of love. Consenting couples often declare love for each other, thereby confirming love across people, an untold number of people at that.

And when Love speaks, the voice of all the gods

Makes heaven drowsy with the harmony. — Berowne (Love’s Labour’s Lost)

And that's a common example of purely phenomenological experiences (identity).

We already know of all kinds of conditions — drug induced epic experiences, synesthesia, mild epilepsy, schizophrenia, whichever hallucinations and illusions, ... Homo sapiens is hardly the perfect perception-organism. And cats jump at shadows. A reasonably strong epistemic standard is warranted here.

________

• The serotonin system and spiritual experiences; Borg, Andrée, Soderstrom, Farde; PubMed, NCBI; Nov 2003

• Are Spiritual Encounters All In Your Head?; Barbara Bradley Hagerty; NPR; May 2009

• The Spiritual Brain: Selective Cortical Lesions Modulate Human Self-Transcendence; Urgesi, Aglioti, Skrap, Fabbro; Jan 2010

• The Sensed-Presence Effect; Michael Shermer; Scientific American; Apr 2010

• Listening to the inner voice; John Hewitt; Medical Xpress; Dec 2013

• Argument from inconsistent revelations; Wikipedia article -

m-theory

1.1kThe argument arbitrarily assigns a status to god that is not justified by anything other than the notion that god is god.

m-theory

1.1kThe argument arbitrarily assigns a status to god that is not justified by anything other than the notion that god is god.

That is to say that god is uncaused only because by definition god is uncaused.

Mean while everything else must have a cause.

That is a rather convenient position that does not require much critical thought. -

jorndoe

4.2kLet me just expand a bit upon

jorndoe

4.2kLet me just expand a bit upon

2. if some God of theism created the universe from something already existing, then whatever comprise the universe "always" existed, perhaps "eternally" (to the extent that's meaningful), and we might as well dispose of the extras, i.e. said God

from the opening post, like creatio ex materia (or creatio ex deo).

An act is temporal, speaking of "to act" is only meaningful by presupposing temporality. (Can relevant counter-examples be presented?)

If said God created the universe out of something pre-existing, something as "old" as God perhaps, but merely transformed this pre-existing something into the universe, then spacetime (or temporality at least) could not merely be an aspect of the universe (the "created"), and said God could not be (wholly) atemporal, which runs contrary to the hypotheses.

if there was a definite earliest time (or "time zero"), then anything that existed at that time, began to exist at that time, and that includes any first causes, gods/God, or whatever else

There was no time at which something atemporal ("outside of time") existed. The atemporal never existed, never can.

I'm not sure how the hypothesizers can (pretend to) make sense of this? -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kIt would then be natural to ask for sufficient and relevant (non-hypothetical) examples of violations of causal closure, in order to justify such extended causation (no special pleading please). — jorndoe

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kIt would then be natural to ask for sufficient and relevant (non-hypothetical) examples of violations of causal closure, in order to justify such extended causation (no special pleading please). — jorndoe

I assume you realize that it would be impossible to observe , or prove, empirically, such a violation of causal closure. It would just appear like an activity without a known cause. Such violations are common, everyday occurrences. We call them free will actions. -

jorndoe

4.2k@Metaphysician Undercover ... which is to assume some sort of "free will" and that they're first causes. That's fine, you just have to sufficiently justify this hypothesis, and that they're "impossible to observe , or prove". (Can there be multiple first causes anyway?)

jorndoe

4.2k@Metaphysician Undercover ... which is to assume some sort of "free will" and that they're first causes. That's fine, you just have to sufficiently justify this hypothesis, and that they're "impossible to observe , or prove". (Can there be multiple first causes anyway?)

Believe whatever, but free will is notoriously strange (and controversial) in philosophy and other disciplines.

Theism tends to take substance dualism serious, where the mind part is associated with "soul" (or "otherworldly spirit"), which is thought to somehow inhabit and move (worldly) bodies. Some notion of "free will" is thought to reside in this "eternal" soul, as a kind of first cause, or an origin, in part. With this line of thinking, mind and free will are made to escape explanation, even in principle, since they're asserted fundamental, and, as such, inexplicable in terms of anything else.

Yet, religious substance dualism still cannot resolve Chalmers mind-body problems, cannot derive qualia, for example, and also runs into the interaction problem. It's a bit like simply deferring one mystery to another (proposed) mystery, and call it a day; it all seems suspiciously self-elevating or incredulous. Leaning on scientific findings, soul ideation of this nature, might be explicable as a result of introspection illusions, that are subject to an inwards self-blindness necessitating cognitive non-closure (exhaustive self-comprehension may not be attainable).

• Free Will Bibliography; Justin Capes; PhilPapers

• What Neuroscience Says about Free Will; Adam Bear; Scientific American; Apr 2016

• Free Will; Psychology Today

• Free Will; SEP article

• Free Will; IEP article

• Free will; Wikipedia article -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k(Can there be multiple first causes anyway?) — jorndoe

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k(Can there be multiple first causes anyway?) — jorndoe

That's a good question, but it is only by assuming the reality of free will, or at least giving it the status of being a logical possibility, that we can proceed to enquire in this direction. Are all cases of free will part of one first cause, or are they separate, individual cases of first cause? If one is a determinist denier, that individual will not even make the effort to proceed toward understanding how one instance of a free will act relates to another. But if we allow for the evidence, that there is free will, we can ask what is it that separates one instance of a free will act from another, and in what sense can this separation be considered "real".

Believe whatever, but free will is notoriously strange (and controversial) in philosophy and other disciplines. — jorndoe

Well, isn't that a surprise? Don't you think that all things in philosophy are strange and controversial, otherwise they wouldn't be philosophy? -

jorndoe

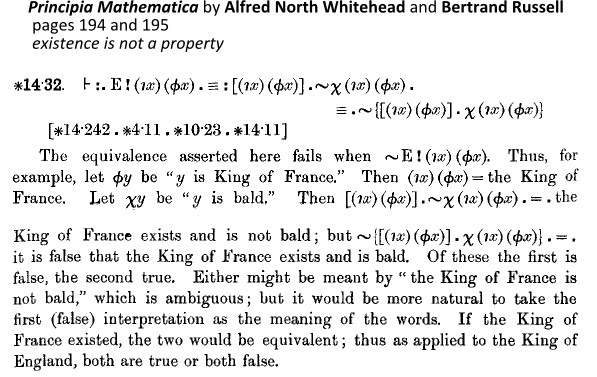

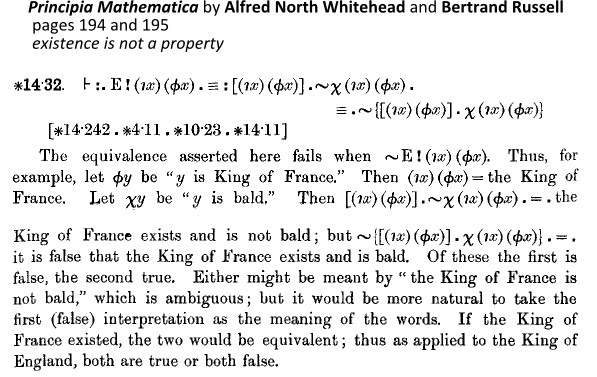

4.2kThings have existence, it's an attribute, a property of things, they exist. — Metaphysician Undercover

jorndoe

4.2kThings have existence, it's an attribute, a property of things, they exist. — Metaphysician Undercover

Maybe?

How can you have a thing already, except it doesn't "have existence"?

Predicate ontologization or existence as ground?

Something's amiss.

Formally, where φ is a predicate (no unrestricted comprehension), x is a variable, and S is a set, existential quantification is properly written as

∃x ∈ S [ φx ]

The ∃ and φ symbols are not interchangeable. Going by Quine, to exist is to be the value of a bound variable, x in the expression.

-

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kMaybe?

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kMaybe?

How can you have a thing already, except it doesn't "have existence"?

Predicate ontologization or existence as ground?

Something's amiss. — jorndoe

I don't see your point. We sense differences around us. We single out one thing as separate from its surrounding, and say that this individuated thing, "exists". Clearly the thing could have been individuated, recognized, named, and even picked up and used, by many different human beings, before some decided to say that this thing "exists".

The issue you refer to seems to be involved with predicating other properties to a subject, prior to attributing existence to that subject, and then falsely concluding that the subject must "exist". In other words there is a category error in assuming that a subject is an object. An assumed subject does not necessarily exist, as we can assume many types of fictitious subjects. When we predicate existence to that subject, we designate that it is an object. To conclude that a subject is necessaily an object, without the appropriate premise is invalid procedure. -

Marty

224

Marty

224

I'm honestly fairly perplexed. Why is this a categorical error? Why is applying the PSR, when applied to a generality fail? Would you mind formalizing your thoughts? In all the work in Pruss, Feser, and others who talk about the PSR, this type of argument has never been mentioned.

I'm also not sure why existence is a property.

So if we desire to apply the PSR to being, there is only the concept to apply it to.

Why? I can obviously apply it to existence it-self, not the concept. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kSorry Marty, if I've confused you. I didn't mean "categorical error", I meant "category mistake".

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kSorry Marty, if I've confused you. I didn't mean "categorical error", I meant "category mistake".

The PSR says that for every existing thing, there is a reason for its existence. A universal, or generality is a concept. Therefore a universal, or generality, is only an existing thing as a concept. So we have two principal categories, particular things, and universals, or generalities. To treat a member of one category as if it were a member of the other category is a category mistake.

If existence itself is a particular thing, and not a concept, can you point to this thing, or describe to me where I might find it.Why? I can obviously apply it to existence it-self, not the concept. — Marty -

Marty

224If existence itself is a particular thing, and not a concept, can you point to this thing, or describe to me where I might find it.

Marty

224If existence itself is a particular thing, and not a concept, can you point to this thing, or describe to me where I might find it.

Well, it's particular type of "thing" - namely the entire world. Definitely not an object/subject in the usual sense, but it's surely not a concept. Conceptual knowledge is existentially neutral. Conceptually, there's no difference between a hundred possible dollars and a hundred actual dollars. So the predicate "existence" adds nothing more to the subject.

Existence surely has to be there prior to any determination on our part.

The PSR says that for every existing thing, there is a reason for its existence. A universal, or generality is a concept. Therefore a universal, or generality, is only an existing thing as a concept. So we have two principal categories, particular things, and universals, or generalities. To treat a member of one category as if it were a member of the other category is a category mistake.

Since existence is not a concept, I take it I can apply the PSR to the thing which is - existence.

Also, this doesn't make any sense with other universals. What about the universal redness? Does that mean you can't apply the universal redness to existing things? -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kWell, it's particular type of "thing" - namely the entire world. Definitely not an object/subject in the usual sense, but it's surely not a concept. — Marty

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kWell, it's particular type of "thing" - namely the entire world. Definitely not an object/subject in the usual sense, but it's surely not a concept. — Marty

Yes, you can do this. You can put all existing things together in one category, and call this "existence". But don't you see that this is a conception? How can you say that apprehending all as one, is not conceptual?

Yes, that's right. Take a look around your room at any object there. How would you propose to apply the universal "redness" to any object in that room? You could apply red paint to an object, but you can't apply redness, the universal. If you name that object "X", you make it a subject, and through predication you can say "X is red". You apply the universal to the subject, not to the object. You apply red paint to the object.Also, this doesn't make any sense with other universals. What about the universal redness? Does that mean you can't apply the universal redness to existing things? — Marty -

jorndoe

4.2kExpressing temporality with tensed verbiage can be difficult; the word "to exist" has a past tense, for example. Our language can express things "existing" tensed — did exist, do exist, may yet come to exist. Though, if we speak of time itself, it would seem odd (or incoherent) to use tense.

jorndoe

4.2kExpressing temporality with tensed verbiage can be difficult; the word "to exist" has a past tense, for example. Our language can express things "existing" tensed — did exist, do exist, may yet come to exist. Though, if we speak of time itself, it would seem odd (or incoherent) to use tense.

Does time exist or is existence temporal?

As suggested by Wittgenstein, we shouldn't let linguistic practices fool us.

Contemporary cosmology will have it that spacetime is an aspect of the universe. It would seem appropriate then, to speak of spacetime/spatiotemporality using non-tensed terminology. I'm not sure how feasible that is, but at least keeping these linguistic curiosities in mind is appropriate.

spacetime is an aspect of the universe, but "before time" is incoherent; causality is temporal, but "a cause of causation" is incoherent — jorndoe -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k...but "a cause of causation" is incoherent — jorndoe

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k...but "a cause of causation" is incoherent — jorndoe

I think we've been through this already in this thread jorndoe. We use "cause" in distinct ways. Aristotle outlined four distinct ways. The type of causation referred to in physical activity was named "efficient cause". The type of causation referred to in free will choices was named "final cause". Since these two are completely distinct types of causes, it is not incoherent to say that one type of causation is prior to, and the cause of the other.

In other words, if physical activity acts as a cause, it is not incoherent to seek the cause of physical activity. This simply requires allowing for a broader category of "cause", such that all causes are not necessarily physical activities. Therefore when we refer to "the cause of causation", "causation" refers to physical activity, and we are seeking the cause of this, as the cause of causation. -

jorndoe

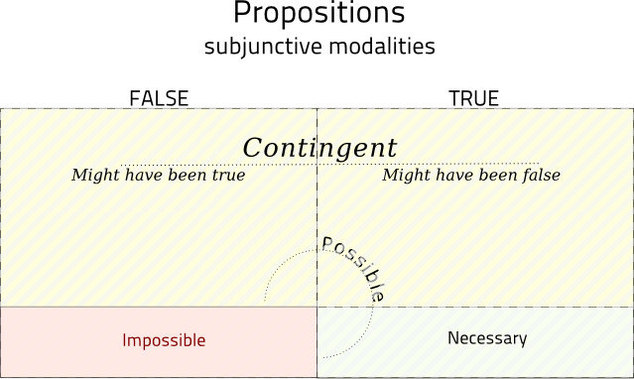

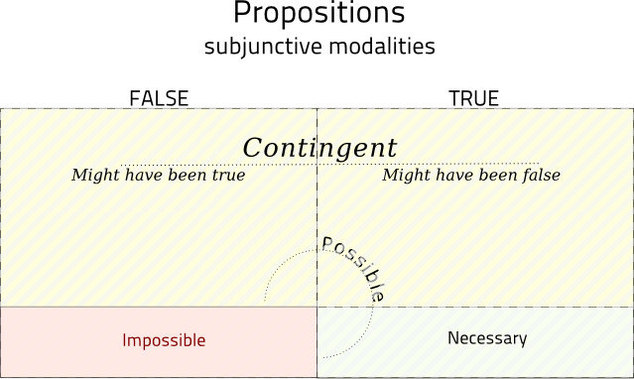

4.2kBriefly on the old contingent versus necessary thing.

jorndoe

4.2kBriefly on the old contingent versus necessary thing.

How does "nothing" categorize here?

It doesn't, it's nonsense.

Ontologization of "nothing" into something is contradictory. "Nothing" isn't something that can be, isn't anything at all. "Nothing" is but a referent-less word (hence quoted), making a stage entry as if it were. Absence of anything and everything also means absence of probabilities, events, conservation, constraints, prohibitions, beer, etc. "Nothing" is merely a linguistic curiosity expressing the missing complement of anything and everything.

How about everything — all of existence — then, how does that categorize (if it does in the first place)?

Does anything necessary necessarily exist?

Well, if you take "nothing" to be the default, then no, at least.

From necessary propositions only necessary propositions follow. — AJ Ayer -

jorndoe

4.2k@Metaphysician Undercover, I'm not going to plead specially to supernatural causation.

jorndoe

4.2k@Metaphysician Undercover, I'm not going to plead specially to supernatural causation.

The kalam/cosmological argument appeals to causation as we know it; otherwise it would have to demonstrate another kind before appealing to it.

The most common use is that causes and effects are events, and events are subsets of changes — they occur, and are temporally contextual — causation consist in related, temporally ordered events.

That's how we know causation.

It so happens this is aligned with conservation. -

Wayfarer

26.1kThe kalam/cosmological argument appeals to causation as we know it. — Jorndoe

Wayfarer

26.1kThe kalam/cosmological argument appeals to causation as we know it. — Jorndoe

Not true, because causation 'as we know it', if scientific causation is the yardstick, which it appears to be, based on your definition, this doesn't recognize formal and final causes. What, for example, causes the laws of motion to have the values they do, and not have some other values, is not a scientific question. -

tom

1.5kNot true, because causation 'as we know it', if scientific causation is the yardstick, which it appears to be, based on your definition, this doesn't recognize formal and final causes. What, for example, causes the laws of motion to have the values they do, and not have some other values, is not a scientific question. — Wayfarer

tom

1.5kNot true, because causation 'as we know it', if scientific causation is the yardstick, which it appears to be, based on your definition, this doesn't recognize formal and final causes. What, for example, causes the laws of motion to have the values they do, and not have some other values, is not a scientific question. — Wayfarer

What is "scientific causation"? When you look at the fundamental laws of nature (the ones whose constants you claim we can't inquire about scientifically) there is no mention of "cause".

Rather, it seems that "cause" in abstraction we invent in order to describe events in terms of a fundamental misconception about the nature of time -i.e. contra what our best theories tell us. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThe kalam/cosmological argument appeals to causation as we know it; otherwise it would have to demonstrate another kind before appealing to it. — jorndoe

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThe kalam/cosmological argument appeals to causation as we know it; otherwise it would have to demonstrate another kind before appealing to it. — jorndoe

I think you're missing the point. The argument demonstrates through logic, that causation as we know it is insufficient to account for existence as we know it. Therefore it demonstrates the need to appeal to a further type of causation to account for existence as we know it.

There is no further need to demonstrate the reality of this other type of causation prior to appealing to it, as you claim, because that's what the argument does, it demonstrates that this other type of causation is necessary, and therefore it must be real. That's what logic does for us, it tells us what must be the case, based on the premises assumed. If there was a need to demonstrate the reality of the conclusion prior to proceeding with the logic, the logic would be rendered useless.

The most common use is that causes and effects are events, and events are subsets of changes — they occur, and are temporally contextual — causation consist in related, temporally ordered events.

That's how we know causation.

It so happens this is aligned with conservation. — jorndoe

Assuming only one type of causation like this leads to an infinite regress of causation. An infinite regress does not account for existence. Therefore we have to assume a different type of cause if we want to proceed toward understanding the cause of existence as we know it.

The traditional cosmological argument, as presented by Aristotle goes beyond the simple claim that a different type of causation is necessary to put an end to the infinite regress. It starts from an analysis of the components of change, and proceeds to determine that the component which appears to be prior to the change itself, the potential for that change, cannot be prior in an absolute sense. There must be an actuality which is prior to all potential. So this actuality cannot be brought about by the potential for that actuality. -

jorndoe

4.2kThe argument demonstrates through logic, that causation as we know it is insufficient to account for existence as we know it. Therefore it demonstrates the need to appeal to a further type of causation to account for existence as we know it. — Metaphysician Undercover

jorndoe

4.2kThe argument demonstrates through logic, that causation as we know it is insufficient to account for existence as we know it. Therefore it demonstrates the need to appeal to a further type of causation to account for existence as we know it. — Metaphysician Undercover

That would be your reading, not Craig's argument (at Leadership University, at Reasonable Faith).

- there are temporal things, therefore there are non-temporal things

- there are natural things, therefore there are unnatural/supernatural things

- there are things that exist, therefore there are things that don't exist

- there is everything, therefore there is something else

- ...?

Craig's aim isn't to show that there are things we don't know. But feel free to show there is a special kind of causation (without extraneous implicit presuppositions, special pleading or the likes), preferably applicable here, or, better yet, in a new opening post (might well be interesting). :)

Just as an aside:

the main reply to the simultaneous causation argument is that the cases appearing to exemplify it are misdescribed — Mellor

Something real exists; not all that exists is real. Fictions and imaginary things exist, for example, and hallucinations similarly, but they're not real. Or that's how I tend to use those words (reality ⊂ existence). (Maybe we could agree on that distinction?)

Assuming only one type of causation like this leads to an infinite regress of causation. An infinite regress does not account for existence. — Metaphysician Undercover

Craig's justification of a non-infinite past duration is largely scientific (Big Bang, entropy, the Borde-Guth-Vilenkin theorem), as mentioned in the opening post, though he evades the no-boundary theories.

We already know that his deductive justification doesn't quite work, doesn't prove that an infinite past duration is impossible. Hilbert's paradox of the Grand Hotel and The diary of Tristram Shandy are known as "veridical paradoxes" because they're not logically inconsistent, they just have certain counter-intuitive implications.

Why wouldn't an infinite past duration account for existence? What would be unaccounted for? For that matter, what else could there be? Non-existence? We don't get to invent things for the occasion. -

jorndoe

4.2kRe: Briefly on the old contingent versus necessary thing.

jorndoe

4.2kRe: Briefly on the old contingent versus necessary thing.

Quoting the British theologian from a 2009 interview:

All explanation, consists in trying to find something simple and ultimate on which everything else depends. And I think that by rational inference what we can get to that’s simple and ultimate is God. But it’s not logically necessary that there should be a God. The supposition ‘there is no God’ contains no contradiction. — Richard Swinburne

Rather, this would have to proven (after answering the ignostic question, and what warrants worship/prayer). -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThat would be your reading, not Craig's argument (at Leadership University, at Reasonable Faith). — jorndoe

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThat would be your reading, not Craig's argument (at Leadership University, at Reasonable Faith). — jorndoe

I really don't find Craig's version of the cosmological argument to be particularly useful, nor do I find it to be completely consistent with versions such as Aristotle's and Aquinas'. And, I think that the changes he makes, perhaps to modernize the argument, distract from the overall coherency of the argument.

Actually I've seen Craig claim that the cause of the universe is another efficient cause, but this produces the incoherency which you have referred to.Craig's aim isn't to show that there are things we don't know. But feel free to show there is a special kind of causation (without extraneous implicit presuppositions, special pleading or the likes), preferably applicable here, or, better yet, in a new opening post (might well be interesting). :) — jorndoe

Craig's justification of a non-infinite past duration is largely scientific (Big Bang, entropy, the Borde-Guth-Vilenkin theorem), as mentioned in the opening post, though he evades the no-boundary theories. — jorndoe

When the cause of the universe is understood to be another efficient cause, we end up with a solution to the problem posed by the cosmological argument, such as Aristotle's solution. Notice that I say "problem", because that's what the argument does, it hands us the problem of "what caused the universe?". It determines that it is necessary that there is a cause of the universe, and gives us the problem of figuring out what that cause is.

The Aristotelian solution is to assume a separate type of efficient cause, which is an eternal circular motion. Any solution which assumes an efficient cause, must assign to that efficient cause, the characteristic of "eternal", because it must be separate from the efficient causation which we know of, as the passing of time, which is proper to our universe. It must be separate from the passing of time, and therefore it is necessarily eternal.

No-boundary theories are consistent with this idea of circular motion, and eternal efficient cause, and are therefore consistent with Craig's solution for the cosmological argument, as he as well assumes efficient causation. The problem is that an eternal efficient cause is itself an incoherent idea. It is contrary to the notion of "efficient cause", that such a cause could be eternal, and therefore the proposal of an eternal efficient cause is oxymoronic, or self-contradictory.

The Neo-Platonist solution, which was adopted by Christianity, becoming Aquinas' solution, is to assume a different type of cause, final cause (the will of God), as the cause of the universe. In this way we avoid the self-contradiction of "eternal efficient cause", by referring to a type of cause which is not an efficient cause at all. This type of cause is not unfamiliar to us, because it is known to exist in the free will choices of human beings. Furthermore, the concept of free will represents final cause as the cause of efficient causes, therefore the cause, or beginning, of chains of efficient causes. And this is what the cosmological argument also indicates, that we need to assume a type of cause which is distinct from the efficient causation which we know, as the cause of the universe.

So, we can associate these two facts: the fact that free will demonstrates to us a type of causation which is distinct from efficient causation, and acts as a beginning, or cause, of a chain of efficient causation, and, the fact that the cosmological argument demonstrates that we need to assume a type of causation which is distinct from efficient causation, as the cause of the universe.

The assumption of an infinite past duration doesn't account for existence, because it doesn't give us the cause of existence. That's what Craig does indicate, that existing things have a beginning, and because they have a beginning, they have a cause. If we assume that the universe does not have a beginning, then it cannot be an existing thing as described. Then we cannot hand to the universe the title of "existence", because existing things are known to have a beginning, and we are denying that the universe has a beginning. So if the universe has an infinite past, "the universe" is necessarily placed in a category other than "existing thing", according to that description, and this designation does nothing for us in accounting for existing things, or "existence" in general, which refers to things that are generated and corrupted, contingent.Why wouldn't an infinite past duration account for existence? — jorndoe -

jorndoe

4.2kI think that the changes he makes, perhaps to modernize the argument, distract from the overall coherency of the argument — Metaphysician Undercover

jorndoe

4.2kI think that the changes he makes, perhaps to modernize the argument, distract from the overall coherency of the argument — Metaphysician Undercover

What objections are they? (That was part of the intent with the opening post.) By the way, please feel free to present your own argument, if you have it reasonably formalized.

Quoting Atheism: A Philosophical Justification (1990), regarding Craig's argument (and two others):

Although there are other contemporary versions of the cosmological argument, these are among the most sophisticated and well argued in contemporary philosophical theology. — Michael Martin

No-boundary theories are [...] consistent with Craig's solution for the cosmological argument — Metaphysician Undercover

No.

Big Bang is not quite justification towards this, entropy may or may not be (also see the fluctuation theorem), the Borde-Guth-Vilenkin theorem more likely is, no-boundary theories are incompatible.2. the universe began to exist

The assumption of an infinite past duration doesn't account for existence, because it doesn't give us the cause of existence. — Metaphysician Undercover

What else is there? Non-existence? :o

which refers to things that are generated and corrupted, contingent — Metaphysician Undercover

? -

jorndoe

4.2kThought I'd just add an extra post here, to increase the count. :D

jorndoe

4.2kThought I'd just add an extra post here, to increase the count. :D

As mentioned, a scientific response seems to involve virtual particle pairs, quantum fluctuations, radioactive decay (temporal indeterminism), spacetime foam/turbulence, the "pressure" of vacuum energy, the Casimir effect, Fomin's quantum cosmogenesis, ... Whereas there are prerequisites for the existence of quantum fluctuations (for example), like spacetime, whichever particular fluctuations themselves are not otherwise determined. Something that can also be found in radioactive decay, where the duration between absorption/excitation and emission/relaxation is non-deterministic. If a scientist was asked about the kind of "nothing" in the post above, then what would you expect them to talk about...? Hollywood scandals at least are something. :)

However, going by the expansion of the universe, spatiality itself is obviously not conserved, not temporally invariant, there's literally more of it by the second.

So where does that "come from"?

Why wouldn't this then be a counter-example to nihil fit ex nihilo, incidentally consistent with scientific findings?

As to conservation, also check the zero-energy universe hypothesis; the sum total of it all comes to exactly zero.

If that holds, then what does it mean to ask where it all "comes from"? -

Wayfarer

26.1kRe the above read David Albert's review of Lawrence Krauss 'Universe from Nothing'.

Wayfarer

26.1kRe the above read David Albert's review of Lawrence Krauss 'Universe from Nothing'.

Basically any appeal to scientific laws begs the question as to origin of those laws.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum