-

Dfpolis

1.3kThat's just as I said: your ideas about science and the PSR are idiosyncratic, and I expect that you will find few allies, regardless of their position on naturalism. And when you add boasts like this, you, frankly, sound like a crank. — SophistiCat

Dfpolis

1.3kThat's just as I said: your ideas about science and the PSR are idiosyncratic, and I expect that you will find few allies, regardless of their position on naturalism. And when you add boasts like this, you, frankly, sound like a crank. — SophistiCat

I was telling what happened, not boasting. The facts are what they are. It doesn't bother me that I am "idiosyncratic." It would bother me if I contradicted the data of experience or if my reasoning were unsound. If you find errors of that sort, please point them out. If you're merely saying that not many people agree with me, I don't consider that a problem.

If you want to make a persuasive case, you don't want to explicitly hinge it on extreme foundational positions that few are likely to accept as an unconditional ultimatum. — SophistiCat

Again, I'm not running for office. I'm trying to be logical and consistent with the facts.

It depends on what you mean by "supernatural and theological explanations." — Dfpolis

I mean the kind of explanations that hinge on the existence of a powerful and largely inscrutable personal agent. — SophistiCat

It would be a philosophical error to begin by positing the existence of God. On the other hand, it is utterly prejudicial to exclude certain kinds of conclusions a priori, as you seem to be doing. We need to follow the facts where they lead, not exclude conclusions before investigating the relevant issues.

Any system that exhibits any regularity has "telos" in this sense, but so what? Any connection to intelligence is far from obvious. — SophistiCat

I am glad that we agree. But, if biological systems do tend toward determinant ends and there is no immediate implication of intelligence, why do naturalists insist that their students say "turtles come ashore and lay eggs," rather than "turtles come ashore to lay eggs"? Isn't this irrational thought control? Clearly, coming ashore is a required step, a means, toward the end of testudine reproduction. -

Dfpolis

1.3kif everything is perception (in Kant's sense, which is not as simple as here represented), then how do you get beyond or outside of it? — tim wood

Dfpolis

1.3kif everything is perception (in Kant's sense, which is not as simple as here represented), then how do you get beyond or outside of it? — tim wood

As I've pointed out, everything can't be perceptions because a perception is always perception of an object by a subject. To say "everything is a perception" is like saying "everything is higher." Both "perception" and "higher" are relational terms and can't be instantiated absent the correlative relata.

To answer you question, because I'm informed by perceptions/appearances/phenomena, I can conclude with apodictic certainty that whatever I am perceiving has the power to so inform me. What does that tell me? Following Plato's suggestion in the Sophist, I think we can agree that whatever can act in any way exists. So, anything that acts to inform me exists. Further, as I have argued previously, what an object is (its individual essence) is convertible with the specification of its possible acts. If it informs me thusly, it must be able to inform me thusly -- giving me some minimal knowledge of its essence.

Thus, perception invariably informs me about the existence and essence of its object. I may add to this actual information a lot of constructive filler and wind up thinking a pink elephant is an Indian elephant, but that error is in judgement, not in the data of experience.

The question amounts to asking how we can pierce the barrier that perception interposes between us and out there. Kant's answer: we cannot. — tim wood

And Kant, like Locke before him, was dead wrong! There is no barrier to be pierced, no gap to be bridged. Had they only read De Anima iii, this whole debate would not be happening. I ask that you carefully consider and respond to the following:

(1) The object informing the subject is identically the subject being informed by the object. Because of this identity, there is never a gap to be bridged. I have put this in neurophysiological terms by pointing out that, in any act of perception, the object's modification of my sensory system is identically my sensory representation of the object. In other words, the one modification of my neural state belongs both to the object (as its action) and to me (as my state). There is shared existence here, or, if you will, existential or dynamical penetration of me by the object of perception. There is no room for a gap and no barrier given this identity.

(2) A second way of grasping the unity here, is to consider the actualization the relevant potentials in the object and subject. The object is sensible/intelligible. The subject able to sense/know. The one act of sensation actualizes both the object's sensibility (making it actually sensed) and the subject's power to sense (making it actually sensing). Similarly, one act of cognition actualizes both the object's intelligibility (making it actually known) and the subject's ability to be informed (making in actually informed). Thus, in each case, the subject and object are joined by a single act -- leaving no space for a barrier or epistic gap.

The fundamental error here is reifying the act of perception. Phenomena are not things to be known, but means of knowing noumena.

You refuse. And it would seem the reason for your refusal - which I find sophistic - is that you define "perception" differently, as "relational." — tim wood

OK, you define a perception in a way that does not implicitly or explicitly include a subject and an object. Alternately, give me an example of a perception that is not a perception of something. You can speak of perceptions in abstraction from their subjects and objects, but there cannot be a perception without an actual subject and object. To forget this is to commit Whitehead's Fallacy of Misplaced Concreteness.

What, exactly, do you mean by "relational"? — tim wood

When I say that a term is relational, mean that it cannot be instantiated without appropriate relata -- without additional existents that it links in some way. For example, "greater than" can be understood in the abstract without reference to concrete values, but any instance of "greater than" is a link between such values.

If it's relational, then it's "out there." Out there invokes the Humean problem. — tim wood

I don't know what you mean by "the Humean problem" here, or even what you mean my "out there." Relations occur in reality, and we form abstract ideas of them by abstracting away individualizing characteristics. -

VoidDetector

70Many biological processes are too complex to calculate mechanically; however, their ends are clear. We cannot calculate how a spider will respond to a fly caught in its web, but its ends predict its behavior. Rejecting teleology’s predictive power is the irrational imposition of a dogmatic faith position. — Dfpolis

VoidDetector

70Many biological processes are too complex to calculate mechanically; however, their ends are clear. We cannot calculate how a spider will respond to a fly caught in its web, but its ends predict its behavior. Rejecting teleology’s predictive power is the irrational imposition of a dogmatic faith position. — Dfpolis

Have you heard of teleonomy? It is teleology evolved. Teleology was left behind after the scientific revolution.

Wikipedia Teleonomy: "Teleonomy is the quality of apparent purposefulness and goal-directedness of structures and functions in living organisms brought about by the exercise, augmentation, and, improvement of reasoning."

Wikipedia Teleonomy vs Teleology: "Teleonomy is sometimes contrasted with teleology, where the latter is understood as a purposeful goal-directedness brought about through human or divine intention."

Teleology concerns religious endeavour. We know that religion/protoscience became modern science in the scientific revolution. So we know religion is obsolete. (For example the computer/internet occurs on modern science, rather than religion/protoscience/archaic science) -

SophistiCat

2.4kI was telling what happened, not boasting. — Dfpolis

SophistiCat

2.4kI was telling what happened, not boasting. — Dfpolis

If you say so :roll:

Any system that exhibits any regularity has "telos" in this sense, but so what? Any connection to intelligence is far from obvious. — SophistiCat

I am glad that we agree. But, if biological systems do tend toward determinant ends — Dfpolis

As do all systems (the concept of a system already implies some degree of orderliness). If telos characterizes everything in existence, simply in virtue of the definition that you give it, then it is a vacuous concept. Your analysis of teleology is wholly inadequate, or rather it is wholly absent. Once again, I recommend that you actually read something on the subject - you may learn something interesting, even if you don't agree with all of it. It's much more fun than railing against imaginary "naturalists," at least as far as I am concerned. -

Wayfarer

26.2kMy problem is that Kant has put together an incoherent and even parochial system. I think I understand his goals and even his outlook, and obviously he has thought deeply, but he seems to have researched no further back than Descartes, Wolff and Locke. — Dfpolis

Wayfarer

26.2kMy problem is that Kant has put together an incoherent and even parochial system. I think I understand his goals and even his outlook, and obviously he has thought deeply, but he seems to have researched no further back than Descartes, Wolff and Locke. — Dfpolis

Alternatively, you could argue that Kant recognised and responded to issues that are particular to the advent of modernity, which the ancients could have had no conceivable way of understanding, given the vast difference in worldviews. He recognised and was responding to implications of modern scientific method, in a way that the ancients and medievals could not.

My problem lies with the claim that we have no knowledge of noumena -- and that is a widely held interpretation of Kant. (As illustrated by a number of quotations I posted yesterday.) — Dfpolis

the noumenal chair cannot be the phenomenal chair because in knowing the phenomenal chair, we know nothing of the noumenal chair. If they were the same being, in knowing one, we would necessarily know the other. So, why add a noumenal chair, when, ex hypothesis, we have no way of knowing it? — Dfpolis

There is no 'noumenal chair'. There are not two things, noumenal and phenomenal, but a single thing understood from two perspectives. And the point of there being two perspectives is to demonstrate the constructivist and conditional nature of knowledge, not to posit a separate unknowable entity. Hence, not a dichotomy, but a duality of mutually implicative concepts.

The difference is that the Aristotelian-Thomistic tradition recognizes that when we actualize sensibility, measurability and intelligibility we are informed about reality. — Dfpolis

How then is it possible that there is such deep conflict in modern culture about the nature of ultimate reality?

And doesn't the Thomistic tradition also emphasise the importance of revelation? In other words, there is a requirement to believe certain articles of faith which are themselves not established on the basis of reason, nor of direct perception, but by way of belief in the Bible. Given that you believe in them, then it is easy to argue for them, but to those who don't believe in them, no amount of argument will persuade them. Aquinas himself says this, doesn't he? -

Dfpolis

1.3kHave you heard of teleonomy? It is teleology evolved. Teleology was left — VoidDetectorHave you heard of teleonomy? It is teleology evolved. Teleology was left behind after the scientific revolution. — VoidDetector

Dfpolis

1.3kHave you heard of teleonomy? It is teleology evolved. Teleology was left — VoidDetectorHave you heard of teleonomy? It is teleology evolved. Teleology was left behind after the scientific revolution. — VoidDetector

Yes, I have. Wayfarer brought it up in the 6th post of this tread and we discussed it. I suggest you read that discussion so that I don't have to go over the same ground again.

That teleology was left behind by the scientific revolution is a historical observation of no probative value.

Wikipedia Teleonomy vs Teleology: "Teleonomy is sometimes contrasted with teleology, where the latter is understood as a purposeful goal-directedness brought about through human or divine intention." — VoidDetector

While "teleology" may be used in that restricted sense by proponents of teleonomy, that is not the general definition of the term, nor is it the definition I used in the OP. For example:

Teleology, (from Greek telos, “end,” and logos, “reason”), explanation by reference to some purpose, end, goal, or function. Traditionally, it was also described as final causality, in contrast with explanation solely in terms of efficient causes (the origin of a change or a state of rest in something). — The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

Teleology concerns religious endeavour. — VoidDetector

In your mind, perhaps. To me this is a discussion about one of Aristotle's four "causes." I do not recall any previous mention of religion in this thread. So, perhaps you have missed the secular aspects of teleology.

So we know religion is obsolete — VoidDetector

Thank you for sharing your faith position so clearly. -

Dfpolis

1.3kIf telos characterizes everything in existence, simply in virtue of the definition that you give it, then it is a vacuous concept — SophistiCat

Dfpolis

1.3kIf telos characterizes everything in existence, simply in virtue of the definition that you give it, then it is a vacuous concept — SophistiCat

I am not discussing it as a concept, but as a mode of explanation -- and that makes its great extension very useful. The fact that every existent is involved in efficient causality makes efficient causality an equally useful tool of understanding.

Your analysis of teleology is wholly inadequate, or rather it is wholly absent. Once again, I recommend that you actually read something on the subject — SophistiCat

If you look at my article, "Mind or Randomness in Evolution" (https://www.academia.edu/27797943/Mind_or_Randomness_in_Evolution) you'll find it well-referenced. If you read my book, God, Science and Mind: The Irrationality of Naturalism, you'll find hundreds of detailed citations. So, I have read "something" on the subject. The positions I "rail" against are specific and documented.

Of course, there is always more to learn. So, if you'd care to make a substantive criticism, or point me in a direction I've missed, that would be appreciated. -

Dfpolis

1.3kAlternatively, you could argue that Kant recognised and responded to issues that are particular to the advent of modernity, which the ancients could have had no conceivable way of understanding, given the vast difference in worldviews. — Wayfarer

Dfpolis

1.3kAlternatively, you could argue that Kant recognised and responded to issues that are particular to the advent of modernity, which the ancients could have had no conceivable way of understanding, given the vast difference in worldviews. — Wayfarer

If the ancients had nothing to say on the issues we're discussing, I wouldn't be citing them.

He recognised and was responding to implications of modern scientific method, in a way that the medievals could not. — Wayfarer

Robert Grosseteste (1175-1253) explicitly laid out the scientific method as we have it today, including controlled experiments. The problem medieval science faced was not poor methodology, but the lack of a critical mass of findings. That said, I don't see Kant's philosophy as depending, in any critical way, on scientific discoveries. (Please correct me if I am wrong.)

The difference is that the Aristotelian-Thomistic tradition recognizes that when we actualize sensibility, measurability and intelligibility we are informed about reality. — Dfpolis

How then is it possible that there is such deep conflict in modern culture about the nature of ultimate reality? — Wayfarer

I am not sure I understand your question, but perhaps the answer is that the Aristotelian-Thomistic view is, as SophistiCat said, seen as "idiosyncratic."

I note, with regret, that you have chosen not to respond to the arguments I specifically asked you to comment upon.

And doesn't the Thomistic tradition also emphasise the importance of revelation? — Wayfarer

No, not in philosophy, though he does consider philosophy to be a "handmaiden" to theology.

Aquinas posits a “twofold mode of truth concerning what we profess about God” (SCG 1.3.2). First, we may come to know things about God through rational demonstration. By demonstration Aquinas means a form of reasoning that yields conclusions that are necessary and certain for those who know the truth of the demonstration’s premises. Reasoning of this sort will enable us to know, for example, that God exists. It can also demonstrate many of God’s essential attributes, such as his oneness, immateriality, eternality, and so forth (SCG 1.3.3). Aquinas is not claiming that our demonstrative efforts will give us complete knowledge of God’s nature. He does think, however, that human reasoning can illuminate some of what the Christian faith professes (SCG 1.2.4; 1.7). Those aspects of the divine life which reason can demonstrate comprise what is called natural theology — Shawn Floyd, Aquinas: Philosophical Theology

In other words, there is a requirement to believe certain articles of faith which are themselves not established on the basis of reason, nor of direct perception, but by way of belief in the Bible. — Wayfarer

This is true of his theology, but not of his philosophy. I am not using faith-based premises in this forum.

I see the goal of philosophy as developing a true and consistent framework for understanding the full rang of human experience, not persuading people. -

Dfpolis

1.3kOk. You see a tree, You tell me: what, exactly, do you see? Hint. It's not, never was, never will be, the tree. In the light of that, care to give an account of how what you see is what you see? — tim wood

Dfpolis

1.3kOk. You see a tree, You tell me: what, exactly, do you see? Hint. It's not, never was, never will be, the tree. In the light of that, care to give an account of how what you see is what you see? — tim wood

I find your claim utterly incoherent. If I see this tree, necessarily, I see this tree. What I do not see is the exhaustive nature of the tree.

I have already explained several times, and you have totally ignored, several times, why there is no epistic gap between me and the tree I see. I will not repeat the same argument yet again, to have it ignored yet again. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kAs I read Kant, the noumenal chair cannot be the phenomenal chair because in knowing the phenomenal chair, we know nothing of the noumenal chair. If they were the same being, in knowing one, we would necessarily know the other. So, why add a noumenal chair, when, ex hypothesis, we have no way of knowing it? — Dfpolis

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kAs I read Kant, the noumenal chair cannot be the phenomenal chair because in knowing the phenomenal chair, we know nothing of the noumenal chair. If they were the same being, in knowing one, we would necessarily know the other. So, why add a noumenal chair, when, ex hypothesis, we have no way of knowing it? — Dfpolis

The problem with this perspective is that "chair" refers to the phenomenon, so there really cannot be a "noumenal chair". All of our concepts of what it means to be a chair, as well as other things, are based in phenomena.

Aristotle on the other hand provided us with a law of identity which identifies the thing itself. His law of identity states that a thing is the same as itself. What this does is create a separation between the individuation and identity which we hand to reality (we individuate and identify "a chair" for example), and the identity which things have, in themselves. So it allows that there are actual individual things in reality, and each has an identity, a "whatness" (what it is) which is proper to it and it alone, regardless of whether human minds have properly individuated and identified the things. -

Wayfarer

26.2kI note, with regret, that you have chosen not to respond to the arguments I specifically asked you to comment upon. — Dfpolis

Wayfarer

26.2kI note, with regret, that you have chosen not to respond to the arguments I specifically asked you to comment upon. — Dfpolis

You mean these?

The contradictoriness of the Kantian doctrine of things in themselves is indubitable...

— T. I. Oizerman, I. Kant's Doctrine of the 'Things in Themselves' and Noumena

Since the thing in itself (Ding an sich) would by definition be entirely independent of our experience of it, we are utterly ignorant of the noumenal realm.

— The Philosophy Pages by Garth Kemerling

Though the noumenal holds the contents of the intelligible world, Kant claimed that man’s speculative reason can only know phenomena and can never penetrate to the noumenon. Man, however, is not altogether excluded from the noumenal because practical reason—i.e., the capacity for acting as a moral agent—makes no sense unless a noumenal world is postulated in which freedom, God, and immortality abide.

— The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica — Dfpolis

Again, I can only repeat what I have already said: that I think all of these statements try to make something out of Kant's 'ding an sich' which he never purported it to be. They all basically accuse Kant of metaphysical speculation.

As the passage I quoted from Emrys Westacott says, "The concept [of the ding an sich] was harshly criticized in his own time and has been lambasted by generations of critics since. A standard objection to the notion is that Kant has no business positing it given his insistence that we can only know what lies within the limits of possible experience (which is pretty well what they all say).

But a more sympathetic reading is to see the concept of the “thing in itself” as a sort of placeholder in Kant's system; it both marks the limits of what we can know and expresses a sense of mystery that cannot be dissolved, the sense of mystery that underlies our unanswerable questions. Through both of these functions it serves to keep us humble."

And I am favouring that sympathetic reading, and furthermore I am confident that these criticisms are based on a misunderstanding of what Kant was trying to say.

(I wrote a bunch more, but will leave it at that for now.) -

Wayfarer

26.2kThe difference is that the Aristotelian-Thomistic tradition recognizes that when we actualize sensibility, measurability and intelligibility we are informed about reality. — Dfpolis

Wayfarer

26.2kThe difference is that the Aristotelian-Thomistic tradition recognizes that when we actualize sensibility, measurability and intelligibility we are informed about reality. — Dfpolis

How then is it possible that there is such deep conflict in modern culture about the nature of ultimate reality?

— Wayfarer

I am not sure I understand your question, but perhaps the answer is that the Aristotelian-Thomistic view is, as SophistiCat said, seen as "idiosyncratic." — Dfpolis

No, it's not that. In your mind, you are arguing for a rational conclusion from a theistic perspective. I am open to that perspective and I too am sceptical that philosophical naturalism as currently conceived will or even can succeed in arriving at a unified vision of the Cosmos (if that is indeed the goal).

But at the same time, I think that your project clearly relies on a faith commitment. Aquinas says that faith is a prerequisite, independently of what can be established by reason. Given that one accepts the articles of faith, then certainly reason and revelation are not in conflict. So even though you say your philosophy stands independently of faith, I think the element provided by faith is implicit in what you're saying.

That is why my question, "How do we know noumena?" is critical -- because it must be some non-standard way of knowing, if it is knowing at all. — Dfpolis

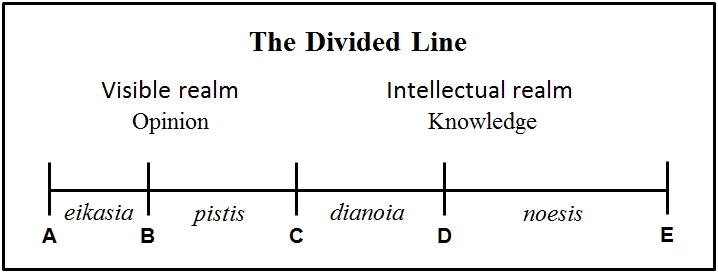

I'll take a shot at this. If you look at the 'Analogy of the Divided Line' in the Republic, then there are different levels or kinds of knowledge (from here):

noesis (immediate intuition, apprehension, or mental 'seeing' of principles)

dianoia (discursive thought)

pistis (belief or confidence)

eikasia (delusion or sheer conjecture)

This is the epistemology of the Republic which has been subject to considerable later commentary and criticism (including by Aristotle). But nevertheless, I think that Aristotelian philosophy still recognises noesis. The basis of 'hylomorphic dualism' is that the intellect (nous) knows the forms of things (which is the exact meaning of 'noesis'), and that the form (morphe) is separable from matter (hyle). So, the 'intellectual intuition' (which Feser and Maritain and other neo-thomists write about), is an insight into the 'intelligible order'. And 'insight into the ideal forms' is close in meaning to the derivation of 'noumenal' (although it can be fairly objected that Kant himself was far from clear that he intended this reading by his use of the word 'noumenal'.)

But the main point is that there is an hierarchy of understanding. The untrained eye, the hoi polloi, the non-philosopher, will see the same things as the philosopher, but won't understand the principles and logic that lie behind them - hence, won't really see them at all, in some important sense; the understanding is occluded or impeded by ignorance - un-wisdom or nescience. And that attitude was formative with respect to modern science, with the caveat that modern science tends to relegate judgements of value to the subjective domain, and then to insist that only what is measurable in the third person, and according to agreed criteria, constitutes a valid object of knowledge.

So, of course, I agree that the approach of modern science is deficient in that fundamental sense. But what has been lost or forgotten is the original sense of there being a 'higher knowledge' (which is the subject of the 'analogy of the divided line' and also 'the analogy of the cave'.) So the general idea is that we don't 'see things as they truly are' - the philosopher has to 'ascend' to that through the refinement of the understanding. -

Andrew M

1.6kOk. You see a tree, You tell me: what, exactly, do you see? Hint. It's not, never was, never will be, the tree. — tim wood

Andrew M

1.6kOk. You see a tree, You tell me: what, exactly, do you see? Hint. It's not, never was, never will be, the tree. — tim wood

In reply to Dfpolis, you say:

Utterly incoherent? Really? — tim wood

In your example you seem to be saying "you see a tree" but also "you do not see the tree", which is a contradiction. It's not clear what you're trying to say. -

Wayfarer

26.2kDoes the phrase "a mere appearance of who knows what unknown object" seem like not positing a "a separate unknowable entity" to you? — Πετροκότσυφας

Wayfarer

26.2kDoes the phrase "a mere appearance of who knows what unknown object" seem like not positing a "a separate unknowable entity" to you? — Πετροκότσυφας

I suppose it does. But the point is, what can you say about this supposed 'unknown entity'? You can't say anything about it, because all you actually know is how it appears to you. So, yes, the 'thing in itself' is in a sense un-knowable, but it's not something other than what we know as an appearance; it's just another perspective on the same thing. So there's not two things: X as it is in itself, and X as it appears to us. There's X, which appears to us in a certain way, which is what we know; we don't know X as it is in itself.

Or as I said above

There are not two things, noumenal and phenomenal, but a single thing understood from two perspectives. And the point of there being two perspectives is to demonstrate the constructivist and conditional nature of knowledge, not to posit a separate unknowable entity. Hence, not a dichotomy, but a duality of mutually implicative concepts. — Wayfarer -

Wayfarer

26.2kI didn't really mean to introduce these long digressions about Kant. I was reacting to Polis' statement that 'The entire structure of Kantian philosophy has been rebutted by modern physics', which I think is quite incorrect. But I'll refrain from further argument as it's simply wheel-spinning at this point.

Wayfarer

26.2kI didn't really mean to introduce these long digressions about Kant. I was reacting to Polis' statement that 'The entire structure of Kantian philosophy has been rebutted by modern physics', which I think is quite incorrect. But I'll refrain from further argument as it's simply wheel-spinning at this point. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kSo, of course, I agree that the approach of modern science is deficient in that fundamental sense. But what has been lost or forgotten is the original sense of there being a 'higher knowledge' (which is the subject of the 'analogy of the divided line' and also 'the analogy of the cave'.) So the general idea is that we don't 'see things as they truly are' - the philosopher has to 'ascend' to that through the refinement of the understanding. — Wayfarer

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kSo, of course, I agree that the approach of modern science is deficient in that fundamental sense. But what has been lost or forgotten is the original sense of there being a 'higher knowledge' (which is the subject of the 'analogy of the divided line' and also 'the analogy of the cave'.) So the general idea is that we don't 'see things as they truly are' - the philosopher has to 'ascend' to that through the refinement of the understanding. — Wayfarer

If you describe dianoia as working with intelligible objects, as application of them, and noesis as understanding intelligible objects, which requires an adequate approach to their very existence, you'll see that the deficiency of modern science is that by its very nature, as a method of application, it is limited to dianoia.

Aristotle in his Nichomachean Ethics, provides a simplified and I believe a more realistic version of the principal divisions of knowledge. He divides theory from practise, such that in comparison to Plato's divisions, theory is assigned to the intellectual realm, practise to the visible. As with Plato's structure, the divisions aren't really "there" within the knowledge, they are artificial, principles of guidance to help us understand the nature of knowledge. In reality, all knowledge consists of a mixture of the two elements, theory and practise, the visible and the intelligible. So even in the highest levels of noesis, contemplation and thinking only with intelligible objects, elements of eikasia, opinion associated with one's practise, enter into the knowledge. No theory (intelligible object) can escape the influence of practise (the visible world), and no practise (activity in the visible world) is free from the influence of theory (the intelligible realm).

So, at the two extremes of the line, the fundamental opinions of practise in the visible world, and the highest levels of theory formulation in the intelligible, Aristotle places intuition. Intuition accounts for how the two extremes of the divided line must directly intermix. This allows for the existence of the person who has good practical intuition, knows the numerous theories which are applicable to a particular situation in the visible world, and how to best apply them in that situation, and also the person who has good theoretical intuition, which is to be well acquainted with the many observances of the visible world in order to understand and produce intelligible theories of a high level.

It is only by allowing for this, intuition, that we can get beyond the realist vs. nominalist trap, which tells us that the foundations of knowledge are to be found in either eternal intelligible Forms, or the norms of society. Intuition allows us to see that it is neither of these, but something else, that which gives us intuition. -

Andrew M

1.6kThat is, the expression, "I see a tree," is perfectly common, perfectly well understood. It just does not happen to be even slightly accurate with respect to the actual process. Think about what light has to do with it. For example, no light, no see the tree. — tim wood

Andrew M

1.6kThat is, the expression, "I see a tree," is perfectly common, perfectly well understood. It just does not happen to be even slightly accurate with respect to the actual process. Think about what light has to do with it. For example, no light, no see the tree. — tim wood

It's common knowledge that you can't see things without light. But then the expression, "I see a tree", doesn't imply otherwise. So what is inaccurate about it? -

Dfpolis

1.3kAll of our concepts of what it means to be a chair, as well as other things, are based in phenomena. — Metaphysician Undercover

Dfpolis

1.3kAll of our concepts of what it means to be a chair, as well as other things, are based in phenomena. — Metaphysician Undercover

Exactly! So, the whole idea of an unknowable noumenal reality is not only superfluous, but literally meaningless.

Aristotle on the other hand provided us with a law of identity which identifies the thing itself. His law of identity states that a thing is the same as itself. What this does is create a separation between the individuation and identity which we hand to reality (we individuate and identify "a chair" for example), and the identity which things have, in themselves. — Metaphysician Undercover

I don't understand what you are saying here. Would you explain how separation can flow out of identity?

So it allows that there are actual individual things in reality, and each has an identity, a "whatness" (what it is) which is proper to it and it alone, regardless of whether human minds have properly individuated and identified the things. — Metaphysician Undercover

I agree with your conclusion. -

Dfpolis

1.3kI note, with regret, that you have chosen not to respond to the arguments I specifically asked you to comment upon. — Dfpolis

Dfpolis

1.3kI note, with regret, that you have chosen not to respond to the arguments I specifically asked you to comment upon. — Dfpolis

You mean these? ... — Wayfarer

No, it was late, and I confused you with Tim Wood. (Mea culpa!) I meant these:

I ask that you carefully consider and respond to the following:

(1) The object informing the subject is identically the subject being informed by the object. Because of this identity, there is never a gap to be bridged. I have put this in neurophysiological terms by pointing out that, in any act of perception, the object's modification of my sensory system is identically my sensory representation of the object. In other words, the one modification of my neural state belongs both to the object (as its action) and to me (as my state). There is shared existence here, or, if you will, existential or dynamical penetration of me by the object of perception. There is no room for a gap and no barrier given this identity.

(2) A second way of grasping the unity here, is to consider the actualization the relevant potentials in the object and subject. The object is sensible/intelligible. The subject able to sense/know. The one act of sensation actualizes both the object's sensibility (making it actually sensed) and the subject's power to sense (making it actually sensing). Similarly, one act of cognition actualizes both the object's intelligibility (making it actually known) and the subject's ability to be informed (making in actually informed). Thus, in each case, the subject and object are joined by a single act -- leaving no space for a barrier or epistic gap.

The fundamental error here is reifying the act of perception. Phenomena are not things to be known, but means of knowing noumena. — Dfpolis

I am favouring that sympathetic reading, and furthermore I am confident that these criticisms are based on a misunderstanding of what Kant was trying to say. — Wayfarer

I do not think that the more sympathetic reading, which I am willing to entertain, resolves the issue that I have, viz. that phenomena do not pose a barrier to understanding noumena, but are the very means by which humans know noumena.

Let me give some of the ways I agree with Kant's objectives.

(1) I see Kant as an heir to the the mystical tradition via his family's Pietism. This justifies, to some degree, his tendency to see the physical world as less than fully real. I sympathize with this, but see it as poorly articulated by Kant.

(2) God grasps noumenal existence directly and completely, while we grasp it only indirectly and via phenomena. So, our knowledge does not even begin to approximate divine knowledge, still it is knowledge of the thing in itself, because we know part of what it can do.

(3) From the divine perspective, the whole space-time continuum is laid out in complete immediacy. I think this motivated Kant to see space, time, and Hume's time-sequenced causality as somehow dependent on the conditions of human existence. Again, I think his articulation of this tension between the human and divine views of reality is wholly inadequate.

(4) Understanding the difference between the divine and human views of causality and temporal sequence is essential to understanding how we can have free will in the face of divine omniscience. Once more, I disagree with his solution.

So, I sympathize with Kant's problematic while rejecting his solution. -

Dfpolis

1.3kUtterly incoherent? Really? Light doesn't have anything to do with it? — tim wood

Dfpolis

1.3kUtterly incoherent? Really? Light doesn't have anything to do with it? — tim wood

Of course light is an essential means of seeing the tree -- but means facilitate, rather than being a barrier to, the end of seeing the tree. The objection here is like saying that laying bricks is a barrier to having a brick house.

Physical interactions between separate points are always mediated. A and B being at different points does not mean that A does not act on B. The tree acts on my sensory system by scattering incident light into my eyes. Does that mean that the resultant modification of my sensory system, which is my sensory representation, is not simultaneously the tree's action? Of course not! So, the action belonging to the tree is identically my representation.

Physical separation does not imply dynamic decoupling. If it did, the solar system would not hold together -- in fact, nothing would. Since information is borne by a system's dynamics, in looking at the flow of information, we need to fix our attention on dynamic coupling, not physical separation. When we do, we discover that the tree's action on me, mediated by light, is identically my neural representation of the tree. -

Dfpolis

1.3kNo, it's not that. In your mind, you are arguing for a rational conclusion from a theistic perspective. — Wayfarer

Dfpolis

1.3kNo, it's not that. In your mind, you are arguing for a rational conclusion from a theistic perspective. — Wayfarer

Theism does not enter into grasping that any perception is the perception of some object by some subject. Atheists can understand that as easily as theists. If you think perception is not relational, please provide an example of perception that does not involve both a perceiver and a perceived.

Aquinas says that faith is a prerequisite, independently of what can be established by reason. — Wayfarer

Yes, to the acceptance of the Christian faith. It is not a prerequisite to rational understanding. If it were, Aquinas would have rejected any conclusion by a pagan such as Aristotle.

Given that one accepts the articles of faith, then certainly reason and revelation are not in conflict. — Wayfarer

That is a non sequitur. Many people accept on faith what reason tell us is nonsense. For example, that the two conflicting accounts of creation in Genesis are both literally true..

I think the element provided by faith is implicit in what you're saying — Wayfarer

What element is that? Please be specific and cite some faith-based premise I used.

If you look at the 'Analogy of the Divided Line' in the Republic, then there are different levels or kinds of knowledge (from here): — Wayfarer

I have no problem with the range of "knowledge/belief" in the diagram, but in the accounts of mystical experience I have read (I've read Christian, Buddhist, Taoist, pagan and atheist reports) no one has recounted the experience of any noumenal object other than transcendent being. Do you know some account in which someone claims to have encountered the noumenal counterpart of a phenomenal object?

Also, while I agree with the range presented, I don't see the enumeration as complete or adequate. Experience is immediate and certain, but is not included. By "experience" here, I mean what is immediately present to awareness, not the consequent embellishments and judgements we may have about what we are aware of.

But the main point is that there is an hierarchy of understanding. — Wayfarer

I have no problem with this concept. I only object to how Kant articulates it. I also agree with you on the biases of so-called "scientific" thought.

o the general idea is that we don't 'see things as they truly are' - the philosopher has to 'ascend' to that through the refinement of the understanding. — Wayfarer

I also agree here, provided that you admit that the little we do see can be quite real, even though it may not be the ultimate reality. -

Dfpolis

1.3kThank you for reflecting on my position.

Dfpolis

1.3kThank you for reflecting on my position.

Here is what I think you mean: that there is a one-to-one correspondence between your neural representation of the tree, and the particular tree you see, and not any other tree or anything else. — tim wood

No, I said what I mean. I am not discussing mappings, but dynamics. The tree acts on me by scattering light into my eye, pushing back when I touch it, etc. Each of these actions modifies my neural state. That modification is both my sensory representation of the tree and the tree's action on me. So, my sensory representation is identically the tree acting on me. Because this identity bespeaks joint existence, there is no epistic gap.

Of course, the dynamics justifies the mapping you're discussing, but the mapping is derivative on the dynamics.

inasmuch as your representation of the tree is a representation, then the - your - representation is not the tree itself. — tim wood

It is not the tree in its full existence. It is the tree as acting on my sensory system. So, it is a projection of the tree in two senses: (1) It is the tree existentially or dynamically penetrating me. The tree is literally acting within me, modifying my neural state for as long as I am sensing it. (2) It is also a projection in the mathematical sense of a dimensionally diminished mapping. The dimensions here are the logically independent things the tree is capable of doing. Of all the possible things it can do, it does a very few in acting on my senses. So, what I get is not a full mapping -- I am not exhaustively informed about the nature of the tree, about all that it can do. Still, what I am informed of is a subset of things the tree can actually do.

Also inasmuch as it is not the tree itself, it differs entirely. — tim wood

This of course is where we differ. Think about the moon. It is dynamically active in the earth's oceans, causing the tides. If you enclose the moon in a tight spherical shall, and restrict your attention to what is inside the shell, you are not considering everything the moon can do, and so you're under-describing the moon. To fully describe it, you have to include its radiance of action, because much of what the moon does, it does outside the circumscribing shell. In the same way, much of what the tree does, it does outside of its circumscribing shell. It not only acts on animal senses as we have been discussing, it changes the ecology both locally and, in a small way, globally. So, if you neglect the tree's radiance of action, you are not giving a full account of what it is to be a tree.

Our sensory representation is not something apart from the tree, but part of the tree's radiance of action. Further, a tree's radiance of action is not separate from the matter of the tree. Rather, it is part of what that matter is -- because it is what that matter, organized as a tree, actually does. Remove it, and you don't have the actual matter of the tree. All you have is something you think of as matter, but which does not act like real matter, and so is not real matter. It is only an abstraction. Part of being real matter is having a radiance of action.

You seem to be completely dismissive, of Kant, and apparently of the problems he perceived. — tim wood

Look at the part of my response to Wayfarer earlier today, beginning with "Let me give some of the ways I agree with Kant's objectives." You'll see that I've thought about why he did what he did. Even though I don't agree with his solution, I appreciate the problems he perceived.

The question is this: you have a representation that manifestly differs from the tree, in particulars and in its entirety. — tim wood

I agree that my representation is not the tree in its entirety. Still, it is a projection of the tree in the two senses I outlined earlier. So, I am informed about the tree: it can do what it is doing to me. If the essence of the tree is the specification of all of its possible acts, then I am informed, in a small way, about the tree's essence. That is the theoretical side.

The practical side, since I am human, I know, in part, how the tree interacts with humans. Since I, and other humans, will always interact with things as humans, all I need to know from a practical point of view is how it interacts with humans.

The question is about knowledge. — tim wood

Yes! And what is knowledge other than the actualization of object's intelligibility? -

SophistiCat

2.4kIf you look at my article, "Mind or Randomness in Evolution" (https://www.academia.edu/27797943/Mind_or_Randomness_in_Evolution) — Dfpolis

SophistiCat

2.4kIf you look at my article, "Mind or Randomness in Evolution" (https://www.academia.edu/27797943/Mind_or_Randomness_in_Evolution) — Dfpolis

Thank you. Having looked over your article, I have no further interest in this conversation. -

Wayfarer

26.2k(1) The object informing the subject is identically the subject being informed by the object. Because of this identity, there is never a gap to be bridged. I have put this in neurophysiological terms by pointing out that, in any act of perception, the object's modification of my sensory system is identically my sensory representation of the object. In other words, the one modification of my neural state belongs both to the object (as its action) and to me (as my state). — Dfpolis

Wayfarer

26.2k(1) The object informing the subject is identically the subject being informed by the object. Because of this identity, there is never a gap to be bridged. I have put this in neurophysiological terms by pointing out that, in any act of perception, the object's modification of my sensory system is identically my sensory representation of the object. In other words, the one modification of my neural state belongs both to the object (as its action) and to me (as my state). — Dfpolis

Well, it seems to me that this is a defense of naive realism. I'm sorry to say that I think the first sentence verges on the nonsensical, as it implies that you are whatever you are looking at - chair, tree, or whatever.

As I tried to argue several pages back, the act of cognition is a complex, whereby a whole range of different kinds of stimuli and judgements are integrated into a whole. And in that act there is also plenty of scope for error. Things may not be what they seem, and the often don't mean what they take them to mean. And Kant really was onto that.

A homely example I sometimes give is 'three men surveying a paddock'. One is a farmer, one a geologist, one a real estate developer. The farmer will see the paddock in terms of how much stock it will support, what kind of pasture it has, whether there's water; the geologist will be looking at rock outcrops, the underlying topography; the real estate developer will be looking at how suitable for building, zoning laws, and so on. So they're all looking at the same paddock but seeing different things; and furthermore, their differing perspectives don't really conflict - it's not as if the real estate developer's view is the right view, and the farmer's the wrong one.

Furthermore, if you go right back into the origins of the 'dialectic of being and becoming' with the Parmenides, then we will see that the Greek philosophers really are questioning our instinctive sense of the reality of sense-perception. Plato, et al, really did distrust the testimony of the senses; in that, he was more like the Vedic sage who sees the world of sensory experience as 'maya', of not being what it seems. I think actually Greek philosophy is, or ought to be, shocking, from the perspective of us modern urbans. We're well-adjusted, we're comfortable, we have a strong sense of what is real and of who we are; I think that philosophy really must call it into question. It's an inconvenient truth (and as a comfortable, well-adjusted member of the bourgeois, that's something that embarrases me. :yikes: )

So when the questions were raised about 'the nature of what is real', philosophy really did take a forensic knife to the 'act of cognition', to how we know what we think we know. And those questions didn't just concern the token chair or apple; they concerned the nature of Justice, Virtue, Beauty, and Truth. (The page from which I took the graphic has a very good analysis of the ethical orientation of The Republic; Uebersax argues that 'the Republic' is actually a metaphor for the human being.)

So the general idea is that we don't 'see things as they truly are' - the philosopher has to 'ascend' to that through the refinement of the understanding.

— Wayfarer

I also agree here, provided that you admit that the little we do see can be quite real, even though it may not be the ultimate reality. — Dfpolis

I think the 'ultimate reality' is the only subject of interest for philosophy - again, that's why it is radical. In Buddhism, there is a term 'yathābhūtaṃ' which refers to the attribute of the Buddha to 'see things as they truly are'. The implication is that we 'puthujjana' ( the Indian equivalent of the hoi polloi) do not see 'things as they are' because of the 'three poisons' of hatred, greed and delusion. These condition our every perception, so we don't 'see things truly'. Of course, in the Secular West, to 'see things truly', it is said, is to see that they're essentially meaningless and purposeless; but this, too, is a mental construct (vikalpa, in Buddhist terminology).

Clearly, the Greek analysis is very different to the Buddhist, but what they do have in common, is a sense that the normal human state is radically deficient. 'Plato was clearly concerned not only with the state of his soul, but also with his relation to the universe at the deepest level. Plato’s metaphysics was not intended to produce merely a detached understanding of reality. His motivation in philosophy was in part to achieve a kind of understanding that would connect him (and therefore every human being) to the whole of reality – intelligibly and if possible satisfyingly. He even seems to have suffered from a version of the more characteristically Judaeo-Christian conviction that we are all miserable sinners, and to have hoped for some form of redemption from philosophy.' (Thomas Nagel, Secular Philosophy and the Religious Temperament.)

So, what we do see is not quite real - that's the point!

Anyway, that is enough out of me, I sit down here at the computer and can type away for hours, but am enrolled in a creative writing course and really must switch focus for a while.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum