-

unenlightened

10kBut if all the rocks were precisely the same size and not ordered, then their arrangement contains no information because it’s by nature disordered. — Wayfarer

unenlightened

10kBut if all the rocks were precisely the same size and not ordered, then their arrangement contains no information because it’s by nature disordered. — Wayfarer

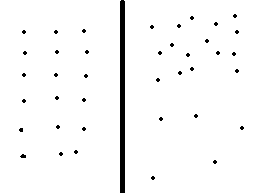

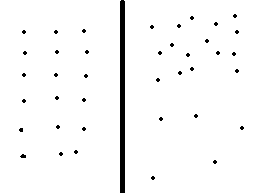

No. this is exactly the opposite of what I am saying. A disordered system contains more information than an ordered one. Your intuition is the opposite because the information it contains is boring. Each pebble has its location in relation to the others, but because there is no order or pattern it looks superficially just like any other disordered arrangement - nothing special.

To illustrate, there is a test for photographic memory that separates a patterned picture into two pictures both of which are pseudo-random. The pattern is only revealed to those who can superimpose one picture onto the other in their mind. -

unenlightened

10kThe point is that you have assumed the capacity to judge between information and disinformation — Metaphysician Undercover

unenlightened

10kThe point is that you have assumed the capacity to judge between information and disinformation — Metaphysician Undercover

No. the point is that I do not at this point distinguish information and disinformation because that is a matter of interpretation, not of information itself. -

unenlightened

10kI'm not making this stuff up. People have been theorising for a while and I am right at the shallow end here.

unenlightened

10kI'm not making this stuff up. People have been theorising for a while and I am right at the shallow end here. -

schopenhauer1

11kI always thought Terrence Deacon's ideas on information were interesting.

schopenhauer1

11kI always thought Terrence Deacon's ideas on information were interesting.

At the bottom level is the natural world, which Deacon characterizes by its subjection to the second law of thermodynamics. When entropy (the Boltzmann kind) reaches its maximum, the equilibrium condition is pure formless disorder. Although there is matter in motion, it is the motion we call heat and nothing interesting is happening. Equilibrium has no meaningful differences, so Deacon calls this the homeodynamics level, using the root homeo-, meaning "the same." There are no meaningful differences here.

At the second level, form (showing differences) emerges. Deacon identifies a number of processes that are negentropic, reducing the entropy locally by doing work against and despite the first level's thermodynamics. This requires constraints, says Deacon, like the piston in a heat engine that constrains the expansion of a hot gas to a single direction, allowing the formless heat to produce directed motion.

Atomic constraints such as the quantum-mechanical bonding of water molecules allow snow crystals to self-organize into spectacular forms, producing order from disorder. Deacon dubs this second level morphodynamic. He sees the emerging forms as differences against the background of unformed sameness. His morphodynamic examples include, besides crystals, whirlpools, Bénard convection cells, basalt columns, and soil polygons, all of which apparently violate the first-level tendency toward equilibrium and disorder in the universe. These are processes that information philosophy calls ergodic.

Herbert Feigl and Charles Sanders Peirce may have been the origin of Bateson's famous idea of a "difference that makes a difference."On Deacon's third level, "a difference that makes a difference" (cf. Gregory Bateson and Donald MacKay) emerges as a purposeful process we can identify as protolife. The quantum physicist Erwin Schrödinger saw the secret of life in an aperiodic crystal, and this is the basis for Deacon's third level. He ponders the role of ATP (adenosine triphosphate) monomers in energy transfer and their role in polymers like RNA and DNA, where the nucleotide arrangements can store information about constraints. He asks whether the order of nucleotides might create adjacent sites that enhance the closeness of certain molecules and thus increase their rate of interaction. This would constitute information in an organism that makes a difference in the external environment, an autocatalytic capability to recruit needed resources. Such a capability might have been a precursor to the genetic code.

Deacon crafts an ingenious model for a minimal "autogenic" system that has a teleonomic (purposeful) character, with properties that might be discovered some day to have existed in forms of protolife. His simplest "autogen" combines an autocatalytic capability with a self-assembly property like that in lipid membranes, which could act to conserve the catalyzing resources inside a protocell.

Autocatalysis and self-assembly are his examples of morphodynamic processes that combine to produce his third-level, teleodynamics. Note that Deacon's simplest autogen need not replicate immediately. Like the near-life of a virus, it lacks a metabolic cycle and does not maintain its "species" with regular reproduction. But insofar as it stores information, it has a primitive ability to break into parts that could later produce similar wholes in the right environment. And the teleonomic information might suffer accidental changes that produce a kind of natural selection.

Deacon introduces a second triad he calls Shannon-Boltzmann-Darwin (Claude, Ludwig, and Charles). He describes it on his Web site www. teleodynamics.com . I would rearrange the first two stages to match his homeodynamic-morphodynamic-teleodynamic triad. This would put Boltzmann first (matter and energy in motion, but both conserved, merely transformed by morphodynamics). A second Shannon stage then adds information (Deacon sees clearly that information is neither matter nor energy); for example, knowledge in an organism's "mind" about the external constraints that its actions can influence.

This stored information about constraints enables the proto-organism in the third stage to act in the world as an agent that can do useful work, that can evaluate its options, and that can be pragmatic (more shades of Peirce) and normative. Thus Deacon's model introduces value into the universe— good and bad (from the organism's perspective). It also achieves his goal of explaining the emergence of perhaps the most significant aspect of the mind: that it is normative and has goals. This is the ancient telos or purpose. — https://www.informationphilosopher.com/solutions/scientists/deacon/ -

Luke

2.7kInformation increases as order decreases. — unenlightened

Luke

2.7kInformation increases as order decreases. — unenlightened

From my brief reading on the subject, I would find this easier to understand if it were rewritten as "novel information increases as unpredictability increases". However, your expression may be more concise. -

Streetlight

9.1k. A disordered system contains more information than an ordered one. — unenlightened

Streetlight

9.1k. A disordered system contains more information than an ordered one. — unenlightened

Yep. In the below, the second, asymmetric ('disordered') organization of dots contains much more information than the first ('ordered') arrangement of dots.

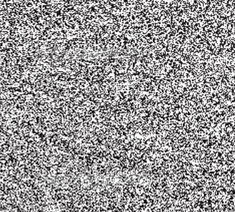

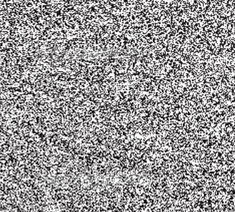

While on the other hand this:

Contains the least information of all (hence commonly known as white noise!)

(One of the reasons why 'order' and 'disorder' can be misleading). -

unenlightened

10kContains the least information of all — StreetlightX

unenlightened

10kContains the least information of all — StreetlightX

Unless it happens to be the code that opens the vault at Fort Knox.

Actually the third picture contains a quite staggering amount of information, it's just (most probably) useless information. But never mind the quality, feel the width. -

Pantagruel

3.6kThere are some really interesting cases in physics around physical entropy and large-scale structures. For example, for any given volume in a state of disorder, in order to be truly random, there must be substructures of a definable size which are actually ordered. If randomness is completely average, you end up with a large scale average distribution, which ends up in fact being ordered, not disordered. Really cool stuff.

Pantagruel

3.6kThere are some really interesting cases in physics around physical entropy and large-scale structures. For example, for any given volume in a state of disorder, in order to be truly random, there must be substructures of a definable size which are actually ordered. If randomness is completely average, you end up with a large scale average distribution, which ends up in fact being ordered, not disordered. Really cool stuff. -

Harry Hindu

5.9kFirst of all, I think all of this is quite true, so I'm not objecting to the basic principle. But what bothers me a bit, is the introduction of 'information' as a metaphysical simple - as a fundamental constituent, in the sense that atoms were once thought to be. — Wayfarer

Harry Hindu

5.9kFirst of all, I think all of this is quite true, so I'm not objecting to the basic principle. But what bothers me a bit, is the introduction of 'information' as a metaphysical simple - as a fundamental constituent, in the sense that atoms were once thought to be. — Wayfarer

"Consciousness" and "mind" are also terms that leave an awful lot of very large, open questions, about what "consciousness" and "mind" is or means or where it originates, yet idealists claim it is fundamental.So - I'm totally open to the notion that 'information is fundamental', but it seems to me to leave an awful lot of very large, open questions, about what 'information' is or means or where it originates.

So when Dennett says, 'oh yes, I'm a materialist, all that exists is matter and energy - and information' - then is he still a materialist? It seems like a very large dodge to me. — Wayfarer

I don't know what Dennett could mean by "materialist" other than meaning that everything is causal. When we talk about "information" we are talking about causal relationships. Effects are about their causes, hence effects carry information about their causes. In providing explanations, we are providing causes to the effect we are explaining.

Tree rings carry information about the age of the tree, not because some mind came along and observed the tree and projected the meaning into the tree rings. The tree rings arose as a result of how the tree grows throughout the year, independent of minds. It is only based on observations of how the tree grows over time that we learn what kind of information the tree rings carry - or what they are about, or mean.

The mind is just another effect of the world, hence it is about the world and informs of the world. Minds are also causes of effects in the world, hence things like written words means, or informs us of, the user's idea and their intent to communicate them.

One can even find information in the use of words other than what the words mean, like how skilled the user is with the language, where they are from in the case of hearing their spoken accent, etc. So information is wherever one looks, or applies their view to some level of the causal chain.

So information isn't necessarily a "thing", but a relationship between things - cause and effect. In this sense, information is fundamental.

Exactly. Order and disorder would be based on some view (larger scale vs. smaller scale). -

Possibility

2.8kBut then what is it? You can’t answer that question - which is the point of the OP. — Wayfarer

Possibility

2.8kBut then what is it? You can’t answer that question - which is the point of the OP. — Wayfarer

As I understand it, information is the capacity to distinguish between possible alternatives. One bit of Shannon information is fundamentally a relation between two possibilities, not two potential alternatives, or two actual alternatives.

So information, at its most fundamental, manifests ‘the difference that makes a difference’ between a binary of possibility: matter/anti-matter, for instance, or true/false or I/0. As such, it is the basic building block of existence. -

Possibility

2.8kI agree with @unenlightened - the third image potentially has the most information, but we just can’t understand how any of it would matter or mean anything.

Possibility

2.8kI agree with @unenlightened - the third image potentially has the most information, but we just can’t understand how any of it would matter or mean anything.

Now, from the perspective of a tiny bug on a printed copy of this image, who is chemically attracted to the inked sections, this image would be a wealth of information... -

schopenhauer1

11k

schopenhauer1

11k

Here's a question:

Does "information" at all solve anything related to the hard question of consciousness? Specifically, I am thinking of qualia. I am still seeing the hard question alluding this as well. There is still an unexplained element of how information explains how color and smell are the same as its physical constituents that cause it. There is a bifurcation there that seems to always elude. You can talk meaningfully about information in terms of physical (neural signals, bio-chemistry, physics) and psychological (the color red can indicate certain things- blood, ripe fruit, red is not green, but close to orange, etc.). However, it does not necessarily close the explanatory gap between the two (Ah, so information means X = Y!). Nope. -

Streetlight

9.1kDoes "information" at all solve anything related to the hard question of consciousness? — schopenhauer1

Streetlight

9.1kDoes "information" at all solve anything related to the hard question of consciousness? — schopenhauer1

Not in any straightforward way. There have been efforts to use information theory in order to shore up a theory of consciousness that accounts for the hard problem ("integrated information theory") but no one seems to understand what its authors are on about. -

Harry Hindu

5.9k. A disordered system contains more information than an ordered one.

Harry Hindu

5.9k. A disordered system contains more information than an ordered one.

— unenlightened

Yep. In the below, the second, asymmetric ('disordered') organization of dots contains much more information than the first ('ordered') arrangement of dots. — StreetlightX

Potential information is being confused as actual information here. When the information is predictable then disorder resolves to order, but that is only done once the pattern is explained - the relationship between the pattern and the cause of the pattern. Until it is explained there are many potential causal relationships, therefore it may seem like there is more information, but that is like thinking that you have multiple choices when making a decision, but all of those choices aren't actual outcomes, only one becomes actual.

Some system has more information than another if it has more causes involved with it than another - kind of like how iron has more information than hydrogen because there were more causal processes involved in the creation of iron over hydrogen. -

unenlightened

10kPotential information is being confused as actual information here. — Harry Hindu

unenlightened

10kPotential information is being confused as actual information here. — Harry Hindu

Come back when you have the faintest idea what we're talking about. I won't be holding my breath.

Hint: an image is what it is. It has no potential, and the information content cannot change except by the destruction of the image. -

unenlightened

10kFor example, for any given volume in a state of disorder, in order to be truly random, there must be substructures of a definable size which are actually ordered. If randomness is completely average, you end up with a large scale average distribution, which ends up in fact being ordered, not disordered. — Pantagruel

unenlightened

10kFor example, for any given volume in a state of disorder, in order to be truly random, there must be substructures of a definable size which are actually ordered. If randomness is completely average, you end up with a large scale average distribution, which ends up in fact being ordered, not disordered. — Pantagruel

Indeed so. I gave the example of black pixels on the left and white pixels on the right as an ordered arrangement A chequerboard configuration would be an example of an ordered mixed distribution.

There's a whole statistical mind-fuck for measuring the degree of disorder. -

schopenhauer1

11k

schopenhauer1

11k

Actually that is an excellent article and he raises exactly issues that I'm talking about. I have heard of IIT and Tononi and Koch's attempt at using it to solve the problem of consciousness. Although probably the most thorough theory using information, information itself just might not be able to get at it. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9k…but no one seems to understand what its authors are on about. — StreetlightX

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9k…but no one seems to understand what its authors are on about. — StreetlightX

Lack of information! -

Wayfarer

26.2kA disordered system contains more information than an ordered one. Your intuition is the opposite because the information it contains is boring. Each pebble has its location in relation to the others, but because there is no order or pattern it looks superficially just like any other disordered arrangement - nothing special. — unenlightened

Wayfarer

26.2kA disordered system contains more information than an ordered one. Your intuition is the opposite because the information it contains is boring. Each pebble has its location in relation to the others, but because there is no order or pattern it looks superficially just like any other disordered arrangement - nothing special. — unenlightened

No - it contains nothing ordered. White noise and piles of rocks are not algorithmically compressible - the position of the rocks, being random, can’t be described by an algorithm.

Web definition of 'information':

what is conveyed or represented by a particular arrangement or sequence of things.

"genetically transmitted information"

(In information theory) a mathematical quantity expressing the probability of occurrence of a particular sequence of symbols, impulses, etc., as against that of alternative sequences.

That last is from Shannon's work.

So, if it's random, then it is not ordered. A 40 kilo pile of pebbles doesn't contain twice as much information as a 20 kilo pile of pebbles - it only contains twice as many pebbles

I don't know what Dennett could mean by "materialist" other than meaning that everything is causal. — Harry Hindu

What Dennett means is that only the objects of physics are real, everything else is derived from that. He says that what we experience as consciousness is really the output of billions of cellular processes which are in themselves unconscious - 'unconscious competence', he calls it.

Does "information" at all solve anything related to the hard question of consciousness? — schopenhauer1

I don't think so. The point I'm making in the OP is that to admit that information is one of the fundamental constituents of reality amounts to admission of defeat for reductionist materialism because it acknowledges that information, however conceived, can't be reduced to matter (or matter-energy). I don't think Dennett realises the implications.

image is what it is. It has no potential, and the information content cannot change except by the destruction of the image. — unenlightened

interestingly, if a holographic image is fragmented, each fragment contains the whole image albeit at a lower resolution. Different topic, though. -

Janus

18kSo, if it's random, then it is not ordered. A 40 kilo pile of pebbles doesn't contain twice as much information as a 20 kilo pile of pebbles - it only contains twice as many pebbles — Wayfarer

Janus

18kSo, if it's random, then it is not ordered. A 40 kilo pile of pebbles doesn't contain twice as much information as a 20 kilo pile of pebbles - it only contains twice as many pebbles — Wayfarer

The pebbles will not all be the same size, so a 40 kilo pile may or may not contain twice as many pebbles as a 20 kilo pile, but it will indeed hold much more information. -

Wayfarer

26.2kThe pebbles will not all be the same size, so a 40 kilo pile may or may not contain twice as many pebbles as a 20 kilo pile, but it will indeed hold much more information. — Janus

Wayfarer

26.2kThe pebbles will not all be the same size, so a 40 kilo pile may or may not contain twice as many pebbles as a 20 kilo pile, but it will indeed hold much more information. — Janus

How so? I'm not asking about information ABOUT the pile, but what information it contains. If you see a bag of stones, do you think it contains any information? If so, what? -

Possibility

2.8kDoes "information" at all solve anything related to the hard question of consciousness? Specifically, I am thinking of qualia. I am still seeing the hard question alluding this as well. There is still an unexplained element of how information explains how color and smell are the same as its physical constituents that cause it. There is a bifurcation there that seems to always elude. You can talk meaningfully about information in terms of physical (neural signals, bio-chemistry, physics) and psychological (the color red can indicate certain things- blood, ripe fruit, red is not green, but close to orange, etc.). However, it does not necessarily close the explanatory gap between the two (Ah, so information means X = Y!). Nope. — schopenhauer1

Possibility

2.8kDoes "information" at all solve anything related to the hard question of consciousness? Specifically, I am thinking of qualia. I am still seeing the hard question alluding this as well. There is still an unexplained element of how information explains how color and smell are the same as its physical constituents that cause it. There is a bifurcation there that seems to always elude. You can talk meaningfully about information in terms of physical (neural signals, bio-chemistry, physics) and psychological (the color red can indicate certain things- blood, ripe fruit, red is not green, but close to orange, etc.). However, it does not necessarily close the explanatory gap between the two (Ah, so information means X = Y!). Nope. — schopenhauer1

Not in any straightforward way. There have been efforts to use information theory in order to shore up a theory of consciousness that accounts for the hard problem ("integrated information theory") but no one seems to understand what its authors are on about. — StreetlightX

The problem with IIT (IMHO) is that it defines both conscious experience and information as actual - consisting of a cause-effect relationship. But the psi it refers to is NOT the most fundamental unit of consciousness they claim it is, anymore than atoms are the most fundamental unit of reality. That’s just as far as scientific certainty goes. Nevertheless, I think the theory has potential, if explored in the context of quantum rather than classical physics. But that’s only an intuitive assessment - I can’t make head or tail of the calculations in either theories, only the interpretations, so I’m not really qualified to take it further.

FWIW - Qualia, as I see it, refers to qualitative potential information or value, in much the same way that probability refers to quantitative potential information. This is information the brain pieces together to make predictions about our interaction with the world - given that the brain doesn’t interact directly with the world, but rather as an allocation of energy (potential) and attention (value) to the various parts of the organism in relation to these predictions. Consciousness would then be the five-dimensional conceptual predictive ‘map’ we each continually reconstruct about ourselves in relation to the world, as a relational structure of both qualitative and quantitative potential information relative to its differentiation from the ongoing sensory event of the organism in 4D spacetime. -

Deleted User

-15But a bag of rocks contains no information... — Wayfarer

Deleted User

-15But a bag of rocks contains no information... — Wayfarer

So now we know the boundaries of your definition of information.

But the dictionary says:

"Information:

2. what is conveyed or represented by a particular arrangement or sequence of things."

https://www.google.com/search?q=information+definitiion&rlz=1C1CHBF_enUS850US850&oq=information+definitiion&aqs=chrome..69i57j0l7.5143j1j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

Does a bag of rocks contain what it conveys? -

Wayfarer

26.2kDoes a bag of rocks contain what it conveys? — ZzzoneiroCosm

Wayfarer

26.2kDoes a bag of rocks contain what it conveys? — ZzzoneiroCosm

It doesn't convey anything. Now, if I was lost on a desert island, and spelt out 'help' with that bag of rocks, and a passing helicopter saw it - then it's conveyed something. -

Possibility

2.8kThe pebbles will not all be the same size, so a 40 kilo pile may or may not contain twice as many pebbles as a 20 kilo pile, but it will indeed hold much more information.

Possibility

2.8kThe pebbles will not all be the same size, so a 40 kilo pile may or may not contain twice as many pebbles as a 20 kilo pile, but it will indeed hold much more information.

— Janus

How so? I'm not asking about information ABOUT the pile, but what information it contains. If you see a bag of stones, do you think it contains any information? If so, what? — Wayfarer

What’s with the distinction from information ABOUT? That’s essentially what information does - it informs one system about another system. But the information we perceive that a pile of stones has as a system is dependent upon our capacity to interact with that system’s capacity to inform.

This highlights the actual/potential misunderstanding about information. What @Janus is referring to is potential information - the pile’s capacity to inform - whereas Wayfarer is referring to actual information: the differentiated result of an interaction between my perceived potential to observe and the pile’s potential to inform. It is the potential information that is more objective - the actual information is subject to your capacity (and willingness) to interact with a pile of stones, and is therefore a limited perspective of information. -

Deleted User

-15It doesn't convey anything. — Wayfarer

Deleted User

-15It doesn't convey anything. — Wayfarer

The bag of rocks doesn't convey the fact that it's a bag of rocks and not a strawberry pie? Then how do you know it's not a strawberry pie?

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum