-

Pfhorrest

4.6kIn this thread I will lay out a hybrid philosophy of mind: one that is eliminativist (nothing has a “mind”) in one sense, panpsychist (everything has a “mind“) in another sense, and emergentist (only some things have a “mind”) in another sense.

Pfhorrest

4.6kIn this thread I will lay out a hybrid philosophy of mind: one that is eliminativist (nothing has a “mind”) in one sense, panpsychist (everything has a “mind“) in another sense, and emergentist (only some things have a “mind”) in another sense.

In a previous thread I have already laid out my physicalist ontology, which straightforwardly rules out the possibility of mental substances, and it is only in that sense that my philosophy of mind is “eliminativist”: nothing has a “mind” if (and only if) by “mind” you mean an associated mental substance separate from the physical substance (such as there is) of its body. But there are other senses of the word “mind”, or “consciousness”, about which I am definitely not eliminativist.

It is useful to distinguish between different things that we might mean by "consciousness" to be clear exactly which of several questions on the topic we wish to address. There is a sense of the word "consciousness" that simply means wakefulness, the opposite of being unconscious or asleep; that sense is not of much philosophical interest. There is another sense of the word that means awareness of something, or knowledge of it; that topic is not directly relevant to philosophy of mind, but rather to epistemology. Of more interest in philosophy of mind are two other sense of the word.

One of them is what Ned Block calls "access consciousness", which is the sense of the word that means self-awareness or self-knowledge, and is the topic of what David Chalmers calls the "easy problem of consciousness"; though I find that topic more substantial, and in a sense harder, and will cover it last. The other of them is what Block calls "phenomenal consciousness", which is the difficult-to-define capacity for experience itself, of any sort, and is the topic of what Chalmers calls the "hard problem of consciousness"; though I find that topic significantly less substantial, and in a sense easier, and will cover it first.

—

On Phenomenal Consciousness

Phenomenal consciousness is perhaps best defined in distinction from what it is not. It is not anything to do with any behavioral properties of a thing. If we stipulate the existence of some being, like a computer artificial intelligence, that behaves identically to a human being, but isn't one, some would still ask whether such a being would actually have the thoughts and feelings, the internal experience, that a real human being would have, or whether it would be merely simulating the external behavior of a being with such thoughts and feelings, such as uttering statements claiming that it feels some way or another.

Philosophers such as David Chalmers have raised the question of whether it is conceivable for there to be a being in every way physically identical to a human being, and so identical in all of its external behavior as well, that nevertheless does not have the internal experience that humans supposedly have, a so-called "philosophical zombie". That kind of experience, independent from anything to do with behavior, is what is meant by "phenomenal consciousness".

There are generally three possibilities when it comes to what kinds of beings have phenomenal consciousness in a physicalist ontology: either nothing has it, not even human beings, because the concept is simply confused nonsense (eliminativism); some beings, like humans, have it, but not all beings, because it only arises from certain complex interactions between physical parts (emergentism); or all beings, not just humans but everything down to trees and rocks and electrons, have it (panpsychism). When it comes to phenomenal consciousness like this, I find both eliminativism and emergentism have fatal flaws, leaving only the possibility of panpsychism — but only with regard to this phenomenal consciousness, not access consciousness, where I am an emergentist, as I’ll cover later.

—

Against Eliminativism

I am against eliminativism for the simple reason that I am directly aware of my own conscious experience, and whatever the nature of that may be, it seems that any philosophical argument that concludes that I am not actually having any conscious experience must have made some misstep somewhere and at best proven that something else mistakenly called "conscious experience" doesn't exist. But beyond my own personal experience, I find arguments put forth by other philosophers, such as Frank Jackson's "Mary's room" thought experiment, to convincingly defeat eliminativism, though not to defeat physicalism itself as they are intended to do.

In the "Mary's room" thought experiment, we imagine a woman named Mary who has been raised her entire life in a black-and-white room experiencing the world only through a black-and-white TV screen, but who has extensively studied and become an expert on the topic of color. She knows everything there is to know about the frequencies of electromagnetic radiation produced by various physical processes, how those interact with nerves in the eye and create signals that are processed by the brain, even the cultural significances of various colors, but she has never herself actually experienced color. We then imagine Mary leaving her room and seeing the color red for the first time, and in doing so, learning something new, despite supposedly knowing everything there was to know about color already: what the color red looks like.

This thought experiment was originally put forth to argue that there is something non-physical involved in the experience of color that Mary could not have learned about by studying the physical science of color, and I don't think it succeeds at all in establishing that, but I do think that it conclusively establishes that there is a difference between knowing, in a third-person fashion, how physical systems behave in various circumstances, and knowing, in the first person, what it's like to be such a physical system in such circumstances. In essence, I think it succeeds merely in showing that we are not philosophical zombies.

A more visceral analogous thought experiment I like to think of is that no amount of studying the physics, biology, psychology, or sociology of sex will ever suffice to answer the question "what's it like to have sex?" Actually doing it yourself is the only way to have that first-person experience; at best, that third-person knowledge of the way things behave can be instrumentally useful to recreating a first-person experience. But even then, you have to actually subject yourself to the experience to experience it, and that experience that can only be known in the first person is all that's meant by phenomenal consciousness.

—

Against Emergentism

I am also against emergentism, regarding phenomenal consciousness at least, on the grounds that it must draw some arbitrary line somewhere, the line between things that are held to be entirely without anything at all like phenomenal consciousness and things that suddenly have it in full, and thus violates my previously established position against fideism. There are two different senses of "emergentism" sometimes distinguished from each other.

One of them, the kind I am not against, is called "weak" emergentism. That merely holds that there are useful aggregate properties to speak of at some larger scales, that ignore irrelevant details at smaller scales; but it doesn't hold than anything genuinely new starts to happen when the larger-scale systems are constructed out of smaller parts. An example of this is temperature, which is a (weakly) emergent property of the motion of molecules in a substance: if you modeled the motion of all the molecules in a substance, you would end up modeling something that exhibited temperature for free, and if that was the scale you were interested in, you could usefully model just that aggregate property of temperature instead and ignore the details of the motion of individual molecules. I have no objection to such "weak" emergentism.

On the other hand, "strong" emergentism holds some wholes to be truly greater than the sums of their parts, and thus that when certain things are arranged in certain ways, wholly new properties apply to the whole that are not mere aggregates or composites of the properties of the parts. Specifically, as regards philosophy of mind, it holds that when physical objects are arranged into the right relations with each other, wholly new mental properties apply to the composite object they create, mental properties that cannot be decomposed into aggregates of the physical properties of the physical objects that went into making the composite object that has these new mental properties.

I do agree with what I think is the intended thrust of the general emergentist position, that consciousness as we ordinarily speak of it is something that just comes about when physical things are arranged in the right way. But I think that consciousness as we ordinarily speak of it is access consciousness, to be addressed later, and that access consciousness is a purely functional, basically mechanistic property that is built up out of, or weakly emerges from, the ordinary physical properties of the physical things that compose an access-conscious being. I think nothing wholly new emerges out of nothing like magic when physical things are arranged in the right way, only abstractions away from the lower-level, smaller-sccale physical properties that ignore the many details that are irrelevant on a higher level or larger scale.

So when it comes to phenomenal consciousness, either it is wholly absent from the most fundamental building blocks of physical things and so is still absent from anything built out of them, including humans — which I've already rejected above — or else it is present at least in humans, as concluded above, and so at least some precursor of it must be present in the stuff out of which humans are built, and the stuff out of which that stuff is built, and so on so that at least something prototypical of phenomenal consciousness as humans experience it is already present in everything, to serve as the building blocks of more advanced kinds of phenomenal consciousness like humans experience.

—

Panpsychism

That latter position is a kind of panpsychism, more specifically the narrower position called pan-proto-experientialism. Panpsychism most broadly defined says that everything has a mind, whatever "mind" may be taken to mean. Pan-experientialism is a form of panpsychism that says everything is at least the subject of mental experience, without making any broader claims about everything having higher mental functions like sentience, intelligence, or sapience. Pan-proto-experientialism is a subform of that, in turn, that says that everything at least has something prototypical of mental experience as we mean it regarding human consciousness, without making any broader claims to the depth or richness of that experience. That is the position that I hold.

But in saying that everything has phenomenal consciousness, I'm not really saying very much of substance. It's a bit akin to how in quantum mechanics, one physical system can be said to "observe" another physical system and in doing so collapse the "observed" system from a state of probabilistic superposition into a definite classical state, but that doesn't really imply anything substantial about the "observer"; it doesn't require something like a human being to do the observation, it just requires any kind of object to interact with the other object. I would even go so far as to say that that quantum-mechanical "observation" can reasonably be equated with the kind of "experience" that I hold to constitute phenomenal consciousness, for as elaborated in my previous thread on the web of reality, I hold experience to be but one perspective on what is really more fundamental, interaction, and likewise quantum mechanical "observation" really just means "interaction".

I'm only really saying that in addition to there being the third-person experience of observing a thing as an object of experience, there is also the first-person experience of being that thing as the subject of experience — because we each know first-hand that there is such a first-person experience of what it's like to be ourselves, which is different from the third-person experiences we have of each other — but that first-person experience needn't amount to much if the thing having the experience is so simple as a rock or atom or electron.

This panpsychism about phenomenal consciousness is not in any way meant to contradict the physicalism I espoused earlier. I think there are only physical things, and that physical things consist only of their empirical properties, which are actually just functional dispositions to interact with observers (who are just other physical things) in particular ways. A subject's phenomenal experience of an object is, on my account, the same event as that object's behavior upon the subject, and the web of such events is what reality is made out of, with the nodes in that web being the objects of reality, each defined by its function in that web of interactions, how it observably behaves in response to what it experiences, or in other words what it does in response to what is done to it.

My only trivial point of agreement with philosophers like Jackson, who fashion themselves to be against physicalism, could be summed up as simply agreeing that we are not philosophical zombies. By definition philosophical zombies could not be discerned from non-zombies from the third person, as only in the first person can one know that oneself is not a philosophical zombie; and the only trivial thing I think Jackson proves is that there is such a first-person experience that we have, the likes of which philosophical zombies would not have, and that, by the rejection of emergentism, everything else must also have.

I don't think philosophical zombies are actually possible or even coherent, but then I also don't think supernatural things are possible or even coherent, so I don't think the predicates "is natural" or "is not a philosophical zombie" really communicate much of interest — they are complete trivialisms when properly understood. (Supernatural beings and philosophical zombies are ontologically quite similar on my account, as for something to be supernatural would be for it to have no observable behavior, and for something to be a philosophical zombie would be for it to have no phenomenal experience. Both of those are just different perspectives on the thing in question being completely cut off from the web of interactions that is reality, and therefore unreal.)

So only in an extremely trivial and useless sense does everything thus "have a mind", inasmuch as everything is subject to the behavior of other things and so has an experience of them. But "minds" in a more useful and robust sense are particular types of complex self-interacting objects, and therefore as subjects have an experience that is heavily of themselves as much as it is of the rest of the world. Everything has awareness of some sort, in that it reacts to things that are done to it — otherwise they would not appear to exist at all, and so not be real at all on my empirical realist account of ontology — but only some things have self-awareness, and that is what the rest of this post will discuss.

—

On Access Consciousness

I hold the experience that a thing has to be a product of that thing's function, just as it's behavior is also a product of function. The mere having of first-person experience is not really anything of note: it is the nature of that experience, as a consequence of the function of the thing having it, that may or may not be worth considering "conscious" in the ordinary sense that we use that word, which I hold, as mentioned above, to be what philosophers call access consciousness.

When it comes to access consciousness, I hold a view called functionalism, which holds that a mental state is not strictly identical to any particular physical state, but rather to the functional role that a physical state holds in the physical system of which it is a part. Mental states are therefore multiply-realizable: different physical systems can instantiate the same functionality, and therefore the same mental states. For instance, if it is possible in principle (as I hold it to be) to build an artificially intelligent computer, that computer could be built using semiconductors, or vacuum tubes, or pneumatic or hydraulic valves, or any other physical substrate of switching signals down different paths, and so long as it still maps the same inputs into it to the same outputs, it still instantiates the same function, and so will still have the same mental states no matter whether they are instantiated in voltages in electric current flowing through wires, pressures in water flowing through pipes, or anything else.

I call this combination of panpsychism about phenomenal consciousness and functionalism about access consciousness "functionalist panpsychism".

As already detailed in my previous thread, I hold that the function of an object, the mapping of the inputs it experiences to the behaviors it outputs, defines every kind of object, not just minds as we ordinarily mean that word. Inasmuch as being a subject of phenomenal experience might make something worth calling "a mind", we might thus considered everything to be "a mind", which is why this position can be considered a form of panpsychism. But in ordinary usage, something being a mind means more than just being some kind of prototypical subject of phenomenal experience, or instantiating any old function or another. It means instantiating some specific kinds of functions that we recognize as mental.

Defining exactly what those functions are in full detail is more the work of psychology (mapping the functions of naturally evolved minds) and computer science (developing functions for artificially created minds) than it is the proper domain of philosophy, but for the rest of this post I will outline a brief sketch of the kinds of functions that I think are important to qualify something as a mind, in the ordinary sense by which we would say that a human definitely has a mind, and a dog probably has a mind, but a tree probably does not, and a rock definitely does not.

—

On Sensations and Perceptions

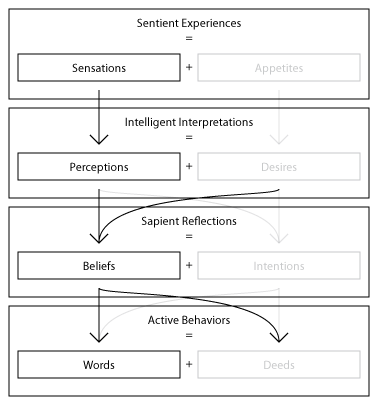

The first of these important functions, which I call "sentience", is to differentiate experiences toward the construction of two separate models, one of them a model of the world as it is, and the other a model of the world as it ought to be. These differentiate aspects of an experience, which, as outlined in my thread on the web of reality, is an interaction between oneself and the world, into those that inform about about the world, including what kind of things are most suited to it, which form the sensitive aspect of the experience; and those that inform about oneself, and what kind of world would be most suited to oneself, which form is the appetitive aspect of the experience.

From these two models we then derive the output behavior from a comparison of the two, so as to attempt to make the world that is into the world that ought to be. This is in distinction from the simpler function of most primitive objects, where experiences directly provoke behaviors in a much simpler stimulus-response mechanism, and no experience is merely indicative of the nature of the world, but all are directly imperative on the next behavior of the object.

Those experiences that are channelled into the model of the world as it ought to be I call "appetites", and I will discuss more on them, their interpretations into desires, and the reflection upon desires to arrive at intentions, in a later thread.

Meanwhile, those experiences that are channelled into the model of the world as it is I call "sensations". Sensations are the raw, uninterpreted experiences, like the seeing of a color, or the hearing of a pitch. When those sensations are then interpreted, pattens in them detected, identified as abstractions, that can then be related to each other symbolically, analytically, that is part of the function that I call "intelligence" (the other part of intelligence handling the equivalent process with appetites), and those interpreted, abstracted sensations output by intelligence are what I call "perceptions", or "intuitions".

—

On Beliefs

None of this is yet sufficient to call something a mind in our ordinary sense of the word. For that, we need all of the above plus also another function, a reflexive function that turns that sentient intelligence back upon the being in question itself, and forms perceptions and desires about its own process of interpreting experiences, and then acts upon itself to critique and judge itself and then filter the conclusions it has come to, accepting or rejecting them as either soundly concluded or not. That reflexive function in general I call "sapience", and the aspect of it concerned with critiquing and judging and filtering perceptions I call "consciousness" proper.

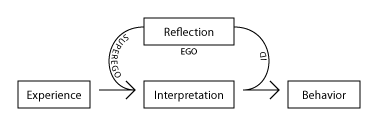

(I see the concepts of "id", "ego", and "superego" as put forward by Sigmund Freud arising out of this reflexive judgement as well, with the third-person view of oneself that one is casting judgement upon being the "id", the third-person view of oneself casting judgement down on one being the "superego", and the first-person view of oneself, being judged by the superego while in turn judging the id, being the "ego"; an illusory tripartite self, as though in a mental hall of mirrors).

And the output of that function — an experience taken as indicative, interpreted into a perception, and accepted by sapient reflection — is what I call a "belief". -

petrichor

325

petrichor

325

I agree with much of your thinking here! It is especially helpful that you make a distinction between the different senses of the word consciousness. When discussing consciousness, people are often talking past one another since they have different things in mind.

There are a couple of things I would like to hear your thoughts on. The first is something I often puzzle over and which might pose a challenge for your view. Supposing that we do have phenomenal consciousness, that we aren't just talking nonsense, how is it that we are able to form thoughts about it and report it through behavior? If I understand your position correctly, it would seem that this phenomenal consciousness would have to be epiphenomenal. The only causes here are the physical causes. There are no mental causes over and above these. So behavior is fully accounted for by the physical causes. Any mental causation would involve overdetermination.

Imagine that there are two kinds of dominoes, sensitive ones, or S-dominoes, which subjectively experience the impacts, and zombie dominoes, or Z-dominoes, which have no phenomenal aspects at all. These two kinds of dominoes are otherwise identical. All their physical properties are the same. If arranged in a certain way, both kinds will impact and fall in the same way. There is no possible way of arranging them and knocking them down that would reveal whether or not they are S-dominoes, even if you arrange them as a complex computer using very large numbers of dominoes. Their behavior, in other words, contains no information about any phenomenal aspects they might have.

It seems to me that this phenomenal consciousness that all physical things are said to have doesn't do any causal work. If the very phenomenality here doesn't have any causal power, how does our brain state come to refer to it? How do we come to have thoughts about our phenomenality? How do we come to talk about it? It is, after all, the underlying micro-physical causes that determine the brain states and therefore the structure of our experiential states. Adding a phenomenal aspect to physical interactions doesn't seem like it would alter the world structurally.

Phenomenal consciousness is perhaps best defined in distinction from what it is not. It is not anything to do with any behavioral properties of a thing. — Pfhorrest

How then do we have thoughts about it and behavior that refers to it, your post for example?

The second thing I am curious to hear your thoughts on is the binding or combination problem. Our brains are very complex arrangements of matter, seemingly with many small parts. But our conscious experience is bound together into a single whole. Notice, for example, that the experience of depth in visual perception requires that something going on in the right hemisphere is bound together with something going on in the left hemisphere.

To see the color red, it must be that you are detecting red light AND NOT green light AND NOT blue light. This requires a number of cone cells and neurons. It is not enough that red-sensitive cones are activated, since they are also activated when you see white, in which case all three cone types are activated. To see yellow, you must be detecting red AND green AND NOT blue. It is not enough that red and green are both activated, as it must be that blue is also NOT activated. Integration is required.

I once built a virtual logic circuit to model RGB color distinctions. The output of each logic gate is only a 1 or a 0. It is never redness or greenness. Similarly, in the brain, it is just neurons firing. And action potentials don't carry color. Even if everything going on in the brain were to somehow ultimately feed to a single neuron, it would only be a matter of that one neuron firing or not firing. The signals coming into that one neuron wouldn't be qualitatively different from those coming into a neuron receiving a signal directly from a cone cell in the retina.

Somehow, what is going on in a bunch of seemingly separate physical objects across different regions of the brain and even maybe parts of the environment must come together as one thing.

From a Chalmers paper:

The most influential formulation of the combination problem was given by William James in The Principles of Psychology (1895). In criticizing “mind-dust theory”, on which mental states are held to be compounds of elemental mental states, James made the following observations:

"Where the elemental units are supposed to be feelings, the case is in no wise altered. Take a hundred of them, shuffle them and pack them as close together as you can (whatever that may mean); still each remains the same feeling it always was, shut in its own skin, windowless, ignorant of what the other feelings are and mean. There would be a hundred-and-first feeling there, if, when a group or series of such feelings were set up, a consciousness belonging to the group as such should emerge. And this 101st feeling would be a totally new fact; the 100 original feelings might, by a curious physical law, be a signal for its creation, when they came together; but they would have no substantial identity with it, nor it with them, and one could never deduce the one from the others, or (in any intelligible sense) say that they evolved it. Take a sentence of a dozen words, and take twelve men and tell to each one word. Then stand the men in a row or jam them in a bunch, and let each think of his word as intently as he will; nowhere will there be a consciousness of the whole sentence. We talk of the ‘spirit of the age,’ and the ‘sentiment of the people,’ and in various ways we hypostatize ‘public opinion.’ But we know this to be symbolic speech, and never dream that the spirit, opinion, sentiment, etc., constitute a consciousness other than, and additional to, that of the several individuals whom the words ‘age,’ ‘people,’ or ‘public’ denote. The private minds do not agglomerate into a higher compound mind."

James is here arguing that experiences (feelings) do not aggregate into further experiences, and that minds do not aggregate into further minds. If this is right, any version of panpsychism that holds that microexperiences (experiences of microphysical entities) combine to yield macroexperiences (experiences of macroscopic entities such as humans) is in trouble.

How is this possible? How do all the little "observations" that are all the microphysical interactions add up to such a bound-together experiential whole, even if it is just a momentary whole?

This kind of wholeness is puzzling. I intuitively tend to think that if something is to have complex structure, it must have parts, and those parts must be separable. In other words, it is a collection of many smaller things. What makes it possible to shape clay also makes it possible to cut it into many tiny pieces. This seems to be a case not of many things being one thing, but of many things simply being near each other and in a certain arrangement. And if something is to be truly whole, truly one thing, it seems to me that it should be a mereological simple. Mereological nihilism seems intuitive to me. But our conscious states seem to be a single whole and yet also have complex structure.

How would this pan-proto-experientialism deal with the combination problem? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kThanks for the response!

Pfhorrest

4.6kThanks for the response!

I think the short answer to both of your questions lies in the ontology of my web of reality, wherein it's explained how I view experience and behavior as two ways of looking at the exact same thing, interaction.

Experience only "is not anything to do with any behavioral properties of a thing" in the sense that you can't tell whether a thing has phenomenal consciousness or not based on what behavior it exhibits. But on my account, experience plays a definite causal role in every behavior of everything: the experience of each thing is the input into its function which prompts its behavior as output. Of course, even non-panpsychists accept that there is some input into things that prompts their behavior; the only novelty on my account, so far as that goes, is to identify that input that nobody denies the existence of with phenomenal experience itself.

Every domino experiences the forces that prompt it to fall over, in one sense or another of "experiences"; I'm just saying that that sense in which a domino can be said to experience the force of another domino hitting it is the same sense, or at least a part of the same sense, in which we experience the force of things hitting us. The difference between the domino and us is that we do a lot more than just absorb the momentum of a thing that hits us and change our bulk motion in response; we're complicated things that have a bunch of complicated internal reactions to things hitting us.

And those complicated internal reactions build up to our unified experience in the same way that our behaviors build up from the behaviors of our constituent atoms, etc, because experiences and behaviors are two ways of looking at the same thing, on my account. I don't see any combination problem in philosophy of mind, at least no more than one could posit a combination problem in ordinary physics: electrons do certain things, sure, but how is it that the behavior of a bunch of electrons adds up to the behavior of the solid-state electronics with which I am composing this message? The actual answer to that is a complicated one, but it's not a philosophical one; it's just an account of how signals pass into one thing as its experience and out of it as its behavior which is in turn the experience of another thing that has another behavior in response, and the aggregate inputs and outputs from the aggregate of those things are their experiences and behaviors. We generally see no problem with this on the behavior side of things -- the behavior of my computer is the aggregate of the behavior of a bunch of electrons, etc -- and I see experiences as literally the same events as behaviors, just viewed from a different perspective, and so no more problematic than the behaviors are. -

Kenosha Kid

3.2kBut in ordinary usage, something being a mind means more than just being some kind of prototypical subject of phenomenal experience, or instantiating any old function or another. It means instantiating some specific kinds of functions that we recognize as mental. — Pfhorrest

Kenosha Kid

3.2kBut in ordinary usage, something being a mind means more than just being some kind of prototypical subject of phenomenal experience, or instantiating any old function or another. It means instantiating some specific kinds of functions that we recognize as mental. — Pfhorrest

A problem completely avoided by not using terminology regarding psychological phenomena to describe non-psychological phenomena. Put it this way: a horse is just a bunch of physical stuff reacting to and acting on a bunch of other physical stuff, and everything is like this. So everything is a horse? No. Psychological phenomena regard brains. It doesn't matter if there's no fundamental difference between a brain and a bowl of soup: it's a classification for specific kinds of things (or behaviours: to be is to do).

But I think that consciousness as we ordinarily speak of it is access consciousness, to be addressed later, and that access consciousness is a purely functional, basically mechanistic property that is built up out of, or weakly emerges from, the ordinary physical properties of the physical things that compose an access-conscious being. — Pfhorrest

Being itself is purely functional though, isn't it? You went to pains in previous threads to establish that there is no real distinction between to be (i.e. to have a bundle of properties) and to do (i.e. to have the potential to behave a certain way). Seems odd now to insist on a distinction between emergent properties and emergent function.

An example of this is temperature, which is a (weakly) emergent property of the motion of molecules in a substance: if you modeled the motion of all the molecules in a substance, you would end up modeling something that exhibited temperature for free, and if that was the scale you were interested in, you could usefully model just that aggregate property of temperature instead and ignore the details of the motion of individual molecules. I have no objection to such "weak" emergentism. — Pfhorrest

There's stuff in between this and strong emergence. Thermodynamic properties of gases in a box are just statistical, large-scale descriptions of fundamental particulate behaviour. However, there is such a thing as collective behaviour. A phonon is an example of this. While phononic behaviour is just motion, you need at least two interacting bodies for these particular modes of motion to emerge. Likewise, while chemical bonds are just modes of electrostatic attraction, they are only possible when you have two or more atoms. There's important stuff between statistics and magic (strong emergentism). So the difference between the thermodynamics of gases, liquids, and solids is derivable but not comprehensible in terms of the dynamics of individual atoms: you have to consider at least two (often more) of something before some behaviours are possible. -

180 Proof

16.4k

180 Proof

16.4k

:100: :up:There's stuff in between this and strong emergence. Thermodynamic properties of gases in a box are just statistical, large-scale descriptions of fundamental particulate behaviour. However, there is such a thing as collective behaviour. A phonon is an example of this. While phononic behaviour is just motion, you need at least two interacting bodies for these particular modes of motion to emerge. Likewise, while chemical bonds are just modes of electrostatic attraction, they are only possible when you have two or more atoms. There's important stuff between statistics and magic (strong emergentism). So the difference between the thermodynamics of gases, liquids, and solids is derivable but not comprehensible in terms of the dynamics of individual atoms: you have to consider at least two (often more) of something before some behaviours are possible. — Kenosha Kid -

RogueAI

3.5k"There are generally three possibilities when it comes to what kinds of beings have phenomenal consciousness in a physicalist ontology..."

RogueAI

3.5k"There are generally three possibilities when it comes to what kinds of beings have phenomenal consciousness in a physicalist ontology..."

Why are you assuming physicalism to be the case? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kA problem completely avoided by not using terminology regarding psychological phenomena to describe non-psychological phenomena. Put it this way: a horse is just a bunch of physical stuff reacting to and acting on a bunch of other physical stuff, and everything is like this. So everything is a horse? No. Psychological phenomena regard brains. It doesn't matter if there's no fundamental difference between a brain and a bowl of soup: it's a classification for specific kinds of things (or behaviours: to be is to do). — Kenosha Kid

Pfhorrest

4.6kA problem completely avoided by not using terminology regarding psychological phenomena to describe non-psychological phenomena. Put it this way: a horse is just a bunch of physical stuff reacting to and acting on a bunch of other physical stuff, and everything is like this. So everything is a horse? No. Psychological phenomena regard brains. It doesn't matter if there's no fundamental difference between a brain and a bowl of soup: it's a classification for specific kinds of things (or behaviours: to be is to do). — Kenosha Kid

I’m mostly using psychological terminology for phenomenal consciousness just because that’s the terminology already used for it, but I can see the historical reasons for its use, just like I can see why quantum mechanics talks about “observers” that can just be inert objects with no brains. It’s talking about things in their capacity to fill a role that we also can fill, and which we tend to associate with our minds. Extending “mind” (or “consciousness” or “observation”) in that sense to everything, even things without brains, is just acknowledging that this capacity that we initially thought was special to us brainy things is not so special; that it’s something else about us brainy things that makes our version of that common feature special.

Being itself is purely functional though, isn't it? You went to pains in previous threads to establish that there is no real distinction between to be (i.e. to have a bundle of properties) and to do (i.e. to have the potential to behave a certain way). Seems odd now to insist on a distinction between emergent properties and emergent function. — Kenosha Kid

I’m not trying to do that, and I don’t see how you can read that in to the passage you responded to.

There's stuff in between this and strong emergence. Thermodynamic properties of gases in a box are just statistical, large-scale descriptions of fundamental particulate behaviour. However, there is such a thing as collective behaviour. A phonon is an example of this. While phononic behaviour is just motion, you need at least two interacting bodies for these particular modes of motion to emerge. Likewise, while chemical bonds are just modes of electrostatic attraction, they are only possible when you have two or more atoms. There's important stuff between statistics and magic (strong emergentism). So the difference between the thermodynamics of gases, liquids, and solids is derivable but not comprehensible in terms of the dynamics of individual atoms: you have to consider at least two (often more) of something before some behaviours are possible. — Kenosha Kid

Okay, I have no objection to that. That is still weak emergence, in that if you modeled the underlying system that that behavior emerges from, you would automatically model the emergent behavior (as in see that behavior emerge in your model; not that you would have a higher-level model of it). I don’t see what bearing that has on phenomenal conscience.

Why are you assuming physicalism to be the case? — RogueAI

Because this thread is a followup to another thread where I argue for a kind of physicalism. -

Kenosha Kid

3.2kI’m mostly using psychological terminology for phenomenal consciousness just because that’s the terminology already used for it, but I can see the historical reasons for its use — Pfhorrest

Kenosha Kid

3.2kI’m mostly using psychological terminology for phenomenal consciousness just because that’s the terminology already used for it, but I can see the historical reasons for its use — Pfhorrest

No objection to that, but using the same terminology to describe the response of an electron to a photon, say, is much like saying everything is a horse. Sometimes metaphor is useful, such as in the talk of "the perspective of a photon" that Mr Bee so objected to earlier. It ceases to be metaphor and becomes misspeaking if you start taking it seriously though. Yes, psychology is ultimately just physical stuff reacting to physical stuff, but so is neurology, biology, chemistry and physics. What makes it psychology is that it is to do with animal minds, neurology: animal brains, biology: living systems, chemistry: structures of atoms, and physics: everything. It just seems like a category error to call physics 'psychology'.

I’m not trying to do that, and I don’t see how you can read that in to the passage you responded to. — Pfhorrest

My misunderstanding then. I read your previous threads in this series as establishing an equivalence between being and doing, one I agree with. What is a 'purely functional' thing, then?

That is still weak emergence, in that if you modeled the underlying system that that behavior emerges from, you would automatically model the emergent behavior (as in see that behavior emerge in your model; not that you would have a higher-level model of it). — Pfhorrest

Yes. I think perhaps it was just not a very illustrative example since it was just the statistical character of pretty much independent parts, whereas emergence really regards collective behaviour: new modes of elementary behaviour not possible with elementary systems. -

RogueAI

3.5kThat's a long thread. I guess my salient point is: are you assuming some non-conscious stuff exists? If so, do you believe consciousness comes from this stuff?

RogueAI

3.5kThat's a long thread. I guess my salient point is: are you assuming some non-conscious stuff exists? If so, do you believe consciousness comes from this stuff? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kWhat's your objection to strong emergence? — Olivier5

Pfhorrest

4.6kWhat's your objection to strong emergence? — Olivier5

it must draw some arbitrary line somewhere, the line between things that are held to be entirely without anything at all like phenomenal consciousness and things that suddenly have it in full, and thus violates my previously established position against fideism. — Pfhorrest

Basically, it's magic. Weakly emergent phenomena build up out of more fundamental phenomena. The kinds of emergent phenomena that Kenosha lists are things that build up out of the phenomena exhibited by basic physical particles: if you model their motion, mass, charge, etc, and model an appropriate aggregate of them just in terms of their motion, mass, charge, etc, you get the emergent phenomena in the model for free. Nothing wholly new suddenly springs into being in the real phenomena that you have to add into the model; the "new" things are all reducible to "old" (more fundamental) things. Strong emergence, on the other hand, would have something wholly new just pop into being suddenly at some point, for no apparent reason (because any reason would tell you what it was about the more fundamental properties that when combined in such a way give rise to this new property, and so would make the "new" phenomenon reducible to the old, and thus only weakly emergent).

It just seems like a category error to call physics 'psychology'. — Kenosha Kid

Agreed, and that's why I wouldn't do that. But saying "everything is phenomenally conscious" isn't doing that, any more than saying "anything can be a quantum mechanical observer" is; "phenomenally conscious" and "quantum mechanical observer" are terms of art divorced from actual psychology, despite having psychological-sounding words in them.

What is a 'purely functional' thing, then? — Kenosha Kid

I meant that in the sense that access conscious has only to do with the particulars of the function of a thing, and is not any kind of metaphysical difference the way that phenomenal consciousness is held to be by non-panpsychists. My overall position is saying that whatever metaphysics is going on with human beings that may be required for our having of a subjective experience, that metaphysics is going on with everything and is not special to humans; the important difference between humans and e.g. rocks, that makes us conscious in the ordinary sense (access conscious), is only the difference in the function of a human vs a rock, not anything metaphysically different.

(Of course, on my account, the only differences there ever are between things are functional differences, but I'm distinguishing my account from views that say otherwise, e.g. views that say there is something metaphysically different about humans, not just functionally different).

I guess my salient point is: are you assuming some non-conscious stuff exists? If so, do you believe consciousness comes from this stuff? — RogueAI

That depends on which sense of "consciousness" you mean. If you mean phenomenal consciousness, then I think everything has that, and that doesn't go against physicalism, because "phenomenal consciousness" on my account is just an ordinary facet of every physical thing, and is not what we actually normally mean by "consciousness". If you mean access consciousness, then I think there are lots and lots of things (most things) that are not access conscious, and our access consciousness, "consciousness" in the sense that we ordinarily mean it, is built up out of that stuff. -

RogueAI

3.5k"If you mean access consciousness, then I think there are lots and lots of things (most things) that are not access conscious, and our access consciousness, "consciousness" in the sense that we ordinarily mean it, is built up out of that stuff."

RogueAI

3.5k"If you mean access consciousness, then I think there are lots and lots of things (most things) that are not access conscious, and our access consciousness, "consciousness" in the sense that we ordinarily mean it, is built up out of that stuff."

You're back to the Hard Problem: how does "active consciousness" emerge from "non-active consciousness" stuff? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kYou're back to the Hard Problem: how does "active consciousness" emerge from "non-active consciousness" stuff? — RogueAI

Pfhorrest

4.6kYou're back to the Hard Problem: how does "active consciousness" emerge from "non-active consciousness" stuff? — RogueAI

I think you're misreading "access" as "active" here.

In any case, access consciousness is the topic of the easy problem. There is no mystery there. Access consciousness is just a kind of functionality. How does the function of my computer emerge from the function of the atoms it's built out of? Very carefully, but not philosophically mysteriously. Likewise, the function of brains emerges from the function of atoms in a similar fashion.

Whatever there is besides that function, whatever metaphysically special thing there also needs to be, that is phenomenal consciousness, which is the subject of the hard problem, and my solution to that is that everything has it, so nothing (phenomenally-)conscious emerges from anything non-(phenomenally-)conscious, because there is nothing non-(phenomenally-)conscious. -

Kenosha Kid

3.2kAgreed, and that's why I wouldn't do that. — Pfhorrest

Kenosha Kid

3.2kAgreed, and that's why I wouldn't do that. — Pfhorrest

By describing it as panpsychism (everything is conscious), you are doing that. Yes, you are demoting consciousness in this context to any physical response function, but that itself is a result of poor choice of terminology. We already have terminology for this. It seems logical to apply the general terminology to the special case. The other way round is, well, back to front.

My overall position is saying that whatever metaphysics is going on with human beings that may be required for our having of a subjective experience, that metaphysics is going on with everything and is not special to humans; the important difference between humans and e.g. rocks, that makes us conscious in the ordinary sense (access conscious), is only the difference in the function of a human vs a rock, not anything metaphysically different. — Pfhorrest

Ah okay, 'purely functional' as opposed to fundamentally metaphysical, not as in divorced from its properties. Yeah, with you on that. I forget that people want to insist we humans are a bit magic, so the distinction went by me. -

Kenosha Kid

3.2k

Kenosha Kid

3.2k -

RogueAI

3.5kI think you're misreading "access" as "active" here.

RogueAI

3.5kI think you're misreading "access" as "active" here.

Yeah.

In any case, access consciousness is the topic of the easy problem. There is no mystery there. Access consciousness is just a kind of functionality. How does the function of my computer emerge from the function of the atoms it's built out of? Very carefully, but not philosophically mysteriously. Likewise, the function of brains emerges from the function of atoms in a similar fashion.

Whatever there is besides that function, whatever metaphysically special thing there also needs to be, that is phenomenal consciousness, which is the subject of the hard problem, and my solution to that is that everything has it, so nothing (phenomenally-)conscious emerges from anything non-(phenomenally-)conscious, because there is nothing non-(phenomenally-)conscious.

You sound like a panpsychist idealist. That's a contradiction, so, do you believe non-mental stuff exists? If no, then you're an idealist, if yes, what kind of stuff is it and how does consciousness emerge from it? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kYou sound like a panpsychist idealist. That's a contradiction — RogueAI

Pfhorrest

4.6kYou sound like a panpsychist idealist. That's a contradiction — RogueAI

You should really read that previous thread on the web of reality. I'm not an idealist, but I am a phenomenalist. Things exist independent of minds, but they're all made of the kind of stuff that can exist in minds: information, observabilia, whatever you want to call it. There is no contradiction there, but yeah, it is a little bit like "everything is in the mind" and "everything is a mind".

The analogy I like to clear that up is: all programs are data, and all data is executable (though most of it does nothing of interest when executed). "Material" stuff is "data"; "minds" are "programs". "Minds" are made of "matter", and all "matter" is metaphysically "mind-like" (though most of it has no interesting "mental activity"). It's only particular data structures (material objects) that do interesting things when executed (that have interesting conscious experience). But everything is still data, that is executable in principle. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kBy describing it as panpsychism (everything is conscious), you are doing that. Yes, you are demoting consciousness in this context to any physical response function, but that itself is a result of poor choice of terminology. — Kenosha Kid

Pfhorrest

4.6kBy describing it as panpsychism (everything is conscious), you are doing that. Yes, you are demoting consciousness in this context to any physical response function, but that itself is a result of poor choice of terminology. — Kenosha Kid

That's the terminology that the philosophers discussing the issue are using though, so if I want to communicate with them I need to talk about the same terms they are. They coined "phenomenal consciousness" as whatever the difference is between a real human and a philosophical zombie, two things that are by definition functionally equivalent.

To deny that there can be any such thing as a philosophical zombie that's different from a real human (as you and I do), we either have to say that real humans just are what they claim philosophical zombies would be like (we have no first-person, subjective, phenomenal experience at all), or else that anything that is functionally identical to a human (like a philosophical zombie is supposed to be) must have the same metaphysical nature as a real human.

The latter can either be because metaphysically boring material stuff, arranged the right way, magically gives rise to something metaphysically novel (strong emergence); or else that whatever it is that a real human is supposed to have that a philosophical zombie wouldn't -- which is not anything functional, because a zombie is functionally identical to a human -- is just something that everything has.

So either:

- we're zombies ourselves,

- magic happens, or

- everything "has a mind" in the sense that these people are talking about.

The last seems the least absurd option to me. -

RogueAI

3.5kSo either:

RogueAI

3.5kSo either:

- we're zombies ourselves,

- magic happens, or

- everything "has a mind" in the sense that these people are talking about.

That's pretty much where I've ended up. -

Olivier5

6.2k

Olivier5

6.2k

You mean this theoretically, or you think it is actually possible and done? Because the cases where it's actually doable are rare. The statistical reduction of temperature to Brownian movement in a perfect gas is the only case that comes to mind, and even this implies all sorts of simplifications (a perfect gas does not actually exist, it's a theoretical simplification of a physical reality). So defined as you do, 'weak emergence' is more a theoretical than proven.Weakly emergent phenomena build up out of more fundamental phenomena. The kinds of emergent phenomena that Kenosha lists are things that build up out of the phenomena exhibited by basic physical particles: if you model their motion, mass, charge, etc, and model an appropriate aggregate of them just in terms of their motion, mass, charge, etc, you get the emergent phenomena in the model for free. — Pfhorrest

LOL. Says the guy who thinks that electron have a micro dose of consciousness... Thanks for the laugh! You can't beat this place for entertainment.Basically, it's magic. — Pfhorrest

Have you ever heard of sexual reproduction? It is a universal property of living systems, and you can't find it anywhere in non living stuff. Stones and stars don't copulate. QED here is a strongly emerging phenomenon.

it must draw some arbitrary line somewhere, the line between things that are held to be entirely without anything at all like phenomenal consciousness and things that suddenly have it in full, — Pfhorrest

I draw the line at life. More precisely, as far as stuff with consciousness are concerned, I include any living species that need to sleep, and that includes quite a few.

Why sleep as a cut-off point? Sleep is near universal among birds and mammals and yet it represents a risky behavior re. predators, a behavior that would not have been selected without a very strong darwinian advantage. It is thought to be a way to refresh the brain and it's information management capacity. Eg memory is affected by lack of sleep in many species, including insects. Thus it seems that sleep as a behavior is connected to learning through complex neuronal systems.

Note that stars and planets and stones and electron don't sleep, other than in the occasional figure of speech, and that one cannot explain sleep as a 'weakly emerging' phenomenon. It's like the example of sex given above...

I finally read you OP. The gross mistake in it, is to assume that human being are made of atoms. It may be what their matter is made of, but in practice human beings are not produced by chemical synthesis. They are made by sexual reproduction, which means that the production of a human being involved copying, random sampling and mixing the genomes of two other human beings (the parents). It is information-intensive.

You and I are made of information, essentially.

You think you're made of your atoms because you don't understand biology. It's a misconception. Let me try and explain.

You must know that our body is composed of water, 75% of the whole weight or so. This water is constantly flowing through our bodies, like water flows in a river. We drink, we urinate, we sweat. Our body manages water as a flow, not as a static reservoir. There is not a single molecule of water inside you right now that has been with you for more than a few weeks. The same applies to proteins that tend to decay and get eliminated and resynthetised all the time.

Life is information bossing matter around. It uses matter, it builds upon it, but it is not defined by any closed set of atoms. It manages matter and energy as fluxes, as pipelines that help maintain a structure, a shape, an in-formation, which is what you are really made of.

If one thinks (as you seem to) that one is made of atoms, then one must see oneself like the river of Heraclitus: always different, inexistent as a stable entity. Because the matter composing your body is constantly 'flowing' through your body like a river flows in its bed. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kHave you ever heard of sexual reproduction? It is a universal property of living systems, and you can't find it anywhere in non living stuff. Stones and stars don't copulate. QED here is a strongly emerging phenomenon. — Olivier5

Pfhorrest

4.6kHave you ever heard of sexual reproduction? It is a universal property of living systems, and you can't find it anywhere in non living stuff. Stones and stars don't copulate. QED here is a strongly emerging phenomenon. — Olivier5

Do you think sexual reproduction involves any processes that are not built up out of the processes of the cells that are built up out of molecules that are built up out of atoms that are built up out of quarks etc? Is there some magic that happens somewhere in there? If not, then that's not strong emergence.

Stones and stars are built out of the same stuff as humans, but they are different things built out of that same stuff. That you can arrange that stuff into a way that will sexually reproduce doesn't mean that everything made of that stuff has to sexually reproduce.

I think you don't understand the difference between strong and weak emergence. Sexual reproduction is a textbook case of weak emergence.

human beings are not produced by chemical synthesis. They are made by sexual reproduction — Olivier5

...which involves a lot of chemical synthesis.

You and I are made of information, essentially. — Olivier5

If you had read the web of reality thread, you'd see I already agree that everything is made of information. Atoms are made of information. Humans are nothing special in that regard.

No single electron, nor any massive particle at all -- nothing that experiences time, in other words -- goes unchanged. They are all like Heraclitus' river: they are constantly being destroyed and re-created by the Higgs field. -

Olivier5

6.2k

Olivier5

6.2k

Now you are changing the goal post. Initially you defined 'strong emergentism' as such:Do you think sexual reproduction involves any processes that are not built up out of the processes of the cells that are built up out of molecules that are built up out of atoms that are built up out of quarks etc? Is there some magic that happens somewhere in there? If not, then that's not strong emergence. — Pfhorrest

Atoms don't reproduce, and molecules don't reproduce. They don't have any 'elementary reproduction', so I don't see any reason to assume they have any 'elementary consciousness' as a way to explain our consciousness... Both are just behaviors that emerged through life., "strong" emergentism holds some wholes to be truly greater than the sums of their parts, and thus that when certain things are arranged in certain ways, wholly new properties apply to the whole that are not mere aggregates or composites of the properties of the parts. — Pfhorrest

The act of reproduction is not something that you can summon by simply putting atoms together in a big unstructured heap or soup. The structure holding those atoms together is what makes it alive, and it is what gets reproduced. And by definition this structure is not contained in its elements. It's more than the sum of its parts.

If you wrote more succinctly, I would read your posts.If you had read the web of reality thread, you'd see I already agree that everything is made of information. — Pfhorrest

Try and understand what I am saying about the Heraclitus river. What is a river? It is not actually defined by the specific molecules of water flowing through it. Otherwise you wouldn't see the same river twice. Likewise your body is not defined by the atoms flowing through it. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kAtoms don't reproduce, and molecules don't reproduce. They don't have any 'elementary reproduction' — Olivier5

Pfhorrest

4.6kAtoms don't reproduce, and molecules don't reproduce. They don't have any 'elementary reproduction' — Olivier5

No, but sexual reproduction is not anything more than a complicated process of atoms interacting in the way that atoms do. Nowhere in that process is it required to suddenly invoke some elan vital or such to make the reproduced organism alive like its parents.

I don't see any reason to assume they have any 'elementary consciousness' as a way to explain our consciousness... Both are just behaviors that emerged through life. — Olivier5

Access consciousness sure is, and that is what I take consciousness in the ordinary way we use the word to be.

But other philosophers ask about “consciousness” in a different sense, something wholly unrelated to behaviors like that, such that something could conceivably, so they say, behave in an access-consciousness way, so far as we can tell in the third person, but not actually experience anything at all in the first person. That having of a first person experience at all, not being any kind of behavior but rather some essential metaphysical difference, either:

- doesn’t happen at all (except we each know first hand that it does happen, at least for ourselves),

- only happens for some things (and since it’s definitionally not anything behavioral, it can’t be built out of the behaviors of the parts it’s made out of, but just suddenly gets added like magic, like some elan vital),

- or happens for everything (but to a degree and in a manner that can vary with the behavior of the thing too, such that only something that behaves like a human has a human-like first-person experience, but a rock with its much simpler behavior still has some first-person experience, just a much simpler one).

Try and understand what I am saying about the Heraclitus river. What is a river? It is not actually defined by the specific molecules of water flowing through it. Otherwise you wouldn't see the same river twice. Likewise your body is not defined by the atoms flowing through it. — Olivier5

Right, I get that, and I’m saying that is true of everything that experiences time (i.e. everything with mass, that moves slower than light); everything is constantly changing, swapping out its constituents, and the only persisting thing is the pattern of information. For anything, even a single electron; even the quarks that make up a proton are constantly changing, blinking out of existence only to be immediately replaced by similar but different particles. Atoms themselves are like rivers.

But that is all an aside, because my underlying point with regard to emergence is that a river can’t do anything that a bunch of water molecules can’t do, because there is nothing to a river but a bunch of water molecules, even though the particular molecules are always changing. For a river to do anything, the water molecules it’s made up of at that moment must do that thing. -

Olivier5

6.2k

Olivier5

6.2k

I never said it was magic, but it's an emerging phenomenon in the sense that it cannot happen outside of life. It has no meaning at the atomic level. No precursor, nothing that compares. It only means something at the cellular level. Below that level, it makes no sense at all.No, but sexual reproduction is not anything more than a complicated process of atoms interacting in the way that atoms do. Nowhere in that process is it required to suddenly invoke some elan vital or such to make the reproduced organism alive like its parents. — Pfhorrest

Sometimes, the whole is more than the sum of its parts.

And yet there's such a thing as a dry river.A river can’t do anything that a bunch of water molecules can’t do, — Pfhorrest -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI never said it was magic, but it's an emerging phenomenon in the sense that it cannot happen outside of life. It has no meaning at the atomic level. No precursor, nothing that compares. It only means something at the cellular level. Below that level, it makes no sense at all. — Olivier5

Pfhorrest

4.6kI never said it was magic, but it's an emerging phenomenon in the sense that it cannot happen outside of life. It has no meaning at the atomic level. No precursor, nothing that compares. It only means something at the cellular level. Below that level, it makes no sense at all. — Olivier5

You're not talking about strong emergence. Strong emergence is definitionally "like magic". If you can take constituent parts, and the things they do, and get them to do something like that together, then that's only weak emergence.

I can't use a single atom as a lever, but I can use a bunch of atoms stuck together as a lever. Leverage "is an emergent phenomenon" in that sense, single atoms have no leverage, but leverage is still just an aggregate of things atoms can do. You don't need something besides just a bunch of atoms stuck together the right way to get a lever: it's not like you need to stick a bunch of atoms together, and add some "essence of lever" to them to make them have leverage. A bunch of atoms just doing what atoms do, in the right configuration, end up doing the work of a lever, with nothing extra required.

That's the defining difference between weak and strong emergence. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kAlthough strong emergence is logically possible, it is uncomfortably like magic. How does an irreducible but supervenient downward causal power arise, since by definition it cannot be due to the aggregation of the micro-level potentialities? Such causal powers would be quite unlike anything within our scientific ken. This not only indicates how they will discomfort reasonable forms of materialism. Their mysteriousness will only heighten the traditional worry that emergence entails illegitimately getting something from nothing. — Mark A. Bedau via Wikipedia

Pfhorrest

4.6kAlthough strong emergence is logically possible, it is uncomfortably like magic. How does an irreducible but supervenient downward causal power arise, since by definition it cannot be due to the aggregation of the micro-level potentialities? Such causal powers would be quite unlike anything within our scientific ken. This not only indicates how they will discomfort reasonable forms of materialism. Their mysteriousness will only heighten the traditional worry that emergence entails illegitimately getting something from nothing. — Mark A. Bedau via Wikipedia -

Pfhorrest

4.6kSomeone PM'd me a question about this thread, I don't know why they didn't just post here, but I thought my response to them might be illustrative for others too. They asked me:

Pfhorrest

4.6kSomeone PM'd me a question about this thread, I don't know why they didn't just post here, but I thought my response to them might be illustrative for others too. They asked me:

If I kick a rock..Will it experience anything? Will it think to itself "I have been kicked!" ?

And I replied:

I don't think a rock ever thinks anything, and it doesn't even feel anything in the way that a human does. It's more like... if you think of it in terms of diminishing degrees of conscious, that's probably the clearest thing.

A human gets kicked and has a whole complicated process of brain activity that they experience, feelings they have, decisions they make about those feelings, and then behavior that they do on account of those decisions.

Other times, even with a human, something can trigger a pure reflex response, and with a lot of lower animals they are entirely reflex response; but we know as humans that we still experience the reflex response, even though it's bypassing our higher thought processes, and it's reasonable to expect that e.g. a sea anemone experiences something like that when its tentacles are touched and it retracts them all by reflex, even though it doesn't have any higher thought processes.

Even a sunflower has a means of detecting light and moving to point toward it, though it has no nervous system at all, and it seems reasonable to think that it has some sort of even more primitive experience of that light, even though it's not even capable of feeling the way an anemone is.

All the way down to rocks, where when you kick it, it still reacts -- it moves, in accordance with the force you applied to it -- but its experience is so diminished that there's practically nothing to speak of at that point.

Still, for the reasons described in the thread you've probably been reading, there's reason to think that something prototypical of human experience still happens to a rock. The major difference between a human experiencing being kicked and a rock experiencing being kicked is that humans have lots of complex reflective (bent-back-upon-ourselves) processes, so we don't just experience the force of being kicked, we experience our nerves firing in response to that force, and all the complicated neurological processes that the activation of those nerves kick off.

I like to think of it as like a modified version of the Cartesian theater. We are mentally seated in the enormous theater that is our brain. Instead of a screen on which we see the outside world, there are only a bunch of tiny pinholes around the theater that let in light from what's happening outside. The theater itself reacts to the light coming through the pinholes, and does a bunch of spectacular things, and that's the show that we're watching.

Most of our experience is experience of ourselves reacting to things. Less complicated subjects, who don't have that complicated mind-theater, only get a pinhole's worth of experience, if that. (And this whole metaphor is on the same shaky ground as the original Cartesian theater anyway, so don't take it too literally; it's just to illustrate the difference between human experience and e.g. a rock's experience). -

Olivier5

6.2kThat's not a source for your assertion, which was about 'strong emergence' being "definitionally like magic". Here all you got is a guy who is of the opinion that it looks like magic. The two ideas are different, because nothing in the definition of emergence is magical. This guy Bedau is just a bit puzzled, as we all are, by self-organising systems, that's all. Just because something looks a bit odd to you doesn't mean it's magical.

Olivier5

6.2kThat's not a source for your assertion, which was about 'strong emergence' being "definitionally like magic". Here all you got is a guy who is of the opinion that it looks like magic. The two ideas are different, because nothing in the definition of emergence is magical. This guy Bedau is just a bit puzzled, as we all are, by self-organising systems, that's all. Just because something looks a bit odd to you doesn't mean it's magical.

My take is that the distinction between weak and strong emergence is confusing a quantitative difference for a qualitative one. Many small 'weakly emergent' phenomenon would presumably add up to a 'strongly emergent' phenomenon. That would easily solve your conendrum. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kMy take is that the distinction between weak and strong emergence is confusing a quantitative difference for a qualitative one. — Olivier5

Pfhorrest

4.6kMy take is that the distinction between weak and strong emergence is confusing a quantitative difference for a qualitative one. — Olivier5

Did you even read the rest of that wikilink? There is a definitional difference between strong and weak emergentism that you’re ignoring. See the part about simulability and analyzabulity especially. It’s nothing to do with self-organization. That is not mysterious.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum