-

Isaac

10.3k

Isaac

10.3k

OK, so in brief (with apologies if any of this is stuff you already know, or misses the point, I just want to be sure we're in the same frame)

Consider that we've no idea what caused the signals which just arrived at our primary visual cortex. We're either expecting them (efficient) or not expecting them (inefficient) and the task is to minimise the surprise (processing requirements) associated with the very next signals. This is just basic Bayesian Brain stuff. This region (V1) delivers the V2 visual cortex with signals relating to basic stuff like outlines, texture etc. The V2 region is in the same boat, it wants to minimise surprise. One way of doing this is by suppressing surprising signals from the V1 cortex. If it did this randomly we'd be in trouble, so it does so according to a model of the signals it expects to receive. At this point the signal splits into two streams, dorsal and ventral, but all along these streams the process continues through layers of expectation models delivering their (modified) signals and being suppressed in turn by the model above.

At some point, several models in, the ventral stream reaches a region which models objects and it will feed forward to areas associated with the object 'car'. Meanwhile, the dorsal stream has been merrily progressing away on the question of how to interact with this hidden state, without the blindest idea what it is.

So.

Point 1 the recognition that it's a car is part of your conscious experience of the hidden state. There can be no quale of a car because modelling it as 'car' is part of the response, quite some way in, in fact. And what's more, plenty of conscious responses have already been initiated by this stage. The dorsal signal doesn't even know it's a car before it's deciding what to do with it (cue amusing but completely unethical experiment with monkeys who've had the connection between their ventral and dorsal signals cut and can pick up and peel a banana but have no idea what to then do with it).

Even if we were to call the sum total of our responses 'quale', we'd have to have 'car' as part of, not the source of, those qualia.

You could say that the responses were to do with what I later determined was a car, but...

Point 2 the models which determine the suppression of forward acting neural signals are themselves informed and updated by signals from other areas of the brain. So no more than a few steps in and whatever hidden states we might like to think started the whole 'car' cascade of signals have been utterly swamped with signals unrelated to that event trying to push them toward the most expected model.

1 and 2 together, I think, make it very hard to talk of the 'quale' of a car in any meaningful sense. If there are 'quale' they certainly can't be properties of any identifiable thing short of 'my entire brain at that point'. We could define them statistically - there are measureable functions of activity in correlated brain areas we could theoretically use to give the quale some very fuzzy-edged owner, some host for it to be the properties of, but I really think doing so would be an act of trying to fit the theory to the facts.

Either way, the private, accessible to introspection, but inaccessible to third party, qualia of 'red' is an absolute non-starter neurologically. -

Isaac

10.3kI think whether the "first order properties" or "second order properties" are called into question depends on which intuition pump we're talking about. Intuition pump (1) looks to me to be about first order properties and how they are ascribed. First order being eg. "the taste of this cauliflower to me now" and second order being eg. "(the taste of this cauliflower to me now) is private and subjective" — fdrake

Isaac

10.3kI think whether the "first order properties" or "second order properties" are called into question depends on which intuition pump we're talking about. Intuition pump (1) looks to me to be about first order properties and how they are ascribed. First order being eg. "the taste of this cauliflower to me now" and second order being eg. "(the taste of this cauliflower to me now) is private and subjective" — fdrake

...which I just noticed. Yes, I think that's true. Intuition pump 1 never really seemed like an intuition pump at all, as Dennet uses them, but more a definition of qualia raw, as it were. An honest attempt to at least start with " I see what you guys mean...but..." -

RogueAI

3.5k"Qualia" names the set of all subjective experiences: my pain of stubbing my toe, your pain of stubbing your toe, Tom's pain of stubbing his toe, my experience of red, Mary's experience of red, etc.

RogueAI

3.5k"Qualia" names the set of all subjective experiences: my pain of stubbing my toe, your pain of stubbing your toe, Tom's pain of stubbing his toe, my experience of red, Mary's experience of red, etc.

As others have pointed out, the amazing thing is qualia exists at all. This three pound lump of meat in my skull produces a phenomenally rich inner mental life? How does that happen??? For awhile, the Hard Problem was swept under the rug by the likes of Dennett, but those guys are dying off. The energy is with the computationalists and panpsychics. I think they're wrong, but at least they're addressing the problem. -

Isaac

10.3kI think they're wrong, but at least they're addressing the problem. — RogueAI

Isaac

10.3kI think they're wrong, but at least they're addressing the problem. — RogueAI

The problem being that you're incredulous?

My incredulity is that you find it at all difficult to believe that 80 billion neurons firing at a rate of up to 1000 per second could produce something as relatively simple as experiencing a phenomena. How many neurons did you imagine it would take? Another few billion? Should I contract some philosophers to investigate that for me, do you think? -

frank

19kBroadly, you're in agreement with RogueAI that Dennett was wrong. Dennett wouldnt allow that humans have phenomenal experience. If it seems to you that he does allow it, read it again and recognize that what he's calling experience is functional consciousness, not phenomenal.

frank

19kBroadly, you're in agreement with RogueAI that Dennett was wrong. Dennett wouldnt allow that humans have phenomenal experience. If it seems to you that he does allow it, read it again and recognize that what he's calling experience is functional consciousness, not phenomenal. -

fdrake

7.2kAn honest attempt to at least start with " I see what you guys mean...but..." — Isaac

fdrake

7.2kAn honest attempt to at least start with " I see what you guys mean...but..." — Isaac

Aye. I read it as an illustration of the kind of thinking that prepares someone to start parsing their experiences in terms of qualia. Another way of phrasing what the doubt is targeted at: if experience events have properties, in what manner do experience event parts bear those properties?

To perhaps illustrate it further: if we allow ourselves to do the usual thing we do, like go from: (1) "The coffee I had today tasted sweet to me" to (2) "The sweetness of the coffee I had today" to (3) "My subjective experience of sweetness from the coffee I had today", we actually describe the experience with different logical structures.

(1) describing a relationship between myself and the coffee I had today (it tasting sweet to me). That's of the form me (relation) coffee, x tastes sweet to y.

(2) predicating a property of the coffee ("sweetness") which I stand in relation to. That's of the form me (relation) (coffee property of sweetness). x tastes ( sweet ( y ) ).

(3) predicating a property of myself which is in relation to the coffee. (my subjective experience) relation (coffee). (sweet-quale-having ( x )) drinking-experience-forming-relation ( y ). Like "the coffee lead to me having a quale of sweetness as a constitutive part of my subjective experience of the coffee".

It's pretty clear that these don't mean the same thing; (1) is a relationship between object level entities in a domain (me, coffee), (2) is a relationship between an object level entity in a domain and a property defined over some unspecified domain (me, coffee property) and (3) a relationship between a property of me and an object of the domain (property of me, coffee).

The lack of domain specificity in (2) and (3) I think is what Dennett's gesturing towards in some of this paragraph:

One dimly imagines taking such cases and stripping them down gradually to the essentials, leaving their common residuum, the way things look, sound, feel, taste, smell to various individuals at various times, independently of how those individuals are stimulated or non- perceptually affected, and independently of how they are subsequently disposed to behave or believe.

If we conceive of the those properties in 2 and 3 as predicating only of me and the coffee, they actually lose context specificity*, the act of predication of the sweet quale to me selects the sweetness from an uncharacterised space of properties - that is, applies the sweet quale to me without consideration of my mood, my tastebuds, the time of day, the chemical composition of the coffee, the temperature of the water it was brewed with, the coffee:water ratio... If those things were impactful on the coffee experience (and we know they can be), the sensation of sweetness could not be modelled accurately as a unary predicate/property. There's just no place in a logical property for more than one term. That is to say, it's a higher order predicate of those things - at least a relation.( recall "independently of how these individuals are stimulated or non-perceptually affected", the context of body and environment has no place in that unary relation, it's just ascribed of "me" or "my subjective state"!)

A qualia advocate might at that point say qualia means those higher order predicates, at which point the vocabulary of "red quales in my subjective experience" becomes suspect regardless.

Intuition pump (1) concludes with:

The mistake is not in supposing that we can in practice ever or always perform this act of purification with certainty, but the more fundamental mistake of supposing that there is such a residual property to take seriously, however uncertain our actual attempts at isolation of instances might be.

I think it is possible to read this as saying that "experience doesn't have properties in any sense", but I believe it's quite uncharitable to do so. Notice that he's talking about a "residual" property, residual after what? The introspective judgements that isolate out properties of experience from the totality of their relevant context, the residual property being what my attention is focussed upon during those acts of introspective judgements regarding a (memory of) experience - which will lead to loss of relevant structure, and a subtracting of details towards some entity which bears the remainder.

So, I think it's more likely to mean that intellectual act I did when talking about "the sweetness of the coffee I had today", fixing some aspect of a memory using introspection, will necessarily lead to error so long as I am treating the content of the sensation event as an entity while splitting it up (like a "picture"). The error being that there was some sort of experiential entity which bore that property, contrasted to the fact that the coffee tasted sweet to me.

It's jumping around the paper a bit, but I think that Dennett also is less suspicious of experiences being described using relations than experiences being described using properties:

He is on quite firm ground, epistemically, when he reports that the relation between his coffee-sipping activity and his judging activity has changed. Recall that this is the factor that Chase and Sanborn have in common: they used to like Maxwell House; now they don't. But unless he carries out on himself the sorts of tests others might carry out on him, his convictions about what has stayed constant (or nearly so) and what has shifted must be sheer guessing.

The Maxwell House example I think goes into that. The "quite firm (epistemic) ground" someone has when describing their experience relationally; Chase and Sanborn have had their tasting relationships with coffee change over time, compared to the looser territory of cutting up aspects of experience using introspective convictions about one's feelings alone.

Chase's intuitive judgments about his qualia constancy are no better off, epistemically, than his intuitive judgments about, say, lighting intensity constancy or room temperature constancy--or his own body temperature constancy. Moving to a condition inside his body does not change the intimacy of the epistemic relation in any special way

A flattening of standards between that which concerns people's self reports of experiences and that which concerns all else. I also don't think that commits him to the thesis that "self reports can be entirely discounted", just that they are "no better off than his intuitive judgements about (external things)". I think it's better to read this apparent skeptical attitude towards inner life as a compensation relative to Cartesian intuitions about the self-evidence of the structure of sensations and what they imply, not simply that they are had in some way:

But then qualia--supposing for the time being that we know what we are talking about--must lose one of their "essential" second-order properties: far from being directly or immediately apprehensible properties of our experience, they are properties whose changes or constancies are either entirely beyond our ken, or inferrable (at best) from "third-person" examinations of our behavioral and physiological reaction patterns (if Chase and Sanborn acquiesce in the neurophysiologists' sense of the term).

Less a claim that psychic life is irrelevant, more a claim that there should be no special treatment for intuitive judgements regarding psychic life. Anticipating a counter argument; if someone tells you that they have pain in their head, I believe this is consistent with trusting them that they had one - if it turned out to be caused by a stiff neck, that they felt it in their head is still data about the pain manifestation, it just turned out that the felt location did not specify the location of the cause even if it was informative about it (stiff neck may lead to headache). -

RogueAI

3.5kThe problem being that you're incredulous?

RogueAI

3.5kThe problem being that you're incredulous?

My incredulity is that you find it at all difficult to believe that 80 billion neurons firing at a rate of up to 1000 per second could produce something as relatively simple as experiencing a phenomena. How many neurons did you imagine it would take? Another few billion? Should I contract some philosophers to investigate that for me, do you think?

OK, what is your explanation for how non-conscious stuff, when assembled the right way, can produce consciousness? Because that seems like magic to me, and to date, materialists have utterly failed to explain the mind-body problem. As I said, they tried to brush it under the rug for awhile, but that's failed. Nobody takes Dennett seriously anymore. -

Isaac

10.3kIf those things were impactful on the coffee experience (and we know they can be), the sensation of sweetness could not be modelled accurately as a unary predicate/property. There's just no place in a logical property for more than one term. That is to say, it's a higher order predicate of those things - at least a relation. — fdrake

Isaac

10.3kIf those things were impactful on the coffee experience (and we know they can be), the sensation of sweetness could not be modelled accurately as a unary predicate/property. There's just no place in a logical property for more than one term. That is to say, it's a higher order predicate of those things - at least a relation. — fdrake

Exactly. This is what I was trying to get at in my reply to @Kenosha Kid earlier from a neurological perspective. 'Sweetness' to the extent we can even identity the sensation is way down the line from the coffee hitting your taste buds. A whole ton of stuff has got involved before then including, crucially, stuff that isn't even part of the event right now. Which prevents the qualist from saying the 'sweetness' is a property of the whole event. A property of your entire life and the environment you've interacted with up to this point, maybe, but that's definitely not on table.

I think it's more likely to mean that intellectual act I did when talking about "the sweetness of the coffee I had today", fixing some aspect of a memory using introspection, can all too readily produce unrealistic accounts of the thing in question. The error being that there was some sort of experiential entity which bore that property, contrasted to the fact that the coffee tasted sweet to me. — fdrake

I agree. I don't know but I think this is where Dennet I leading with...

he pretends to be able to divorce his apprehension (or recollection) of the quale--the taste, in ordinary parlance--from his different reactions to the taste. But this apprehension or recollection is itself a reaction to the presumed quale, so some sleight-of-hand is being perpetrated--innocently no doubt--by Chase — Dennet

Some people might say Dennet's denying there's anything to 'experience, it just goes from input to response, but I think he's saying, and I agree, that the recollection divorced from a response is incoherent. We always 'experience' events post hoc, never in real time. The experience is a constructed story told later (sometimes much later).

A flattening of standards between that which concerns people's self reports of experiences and that which concerns all else. — fdrake

Yes. I like the conclusion of the neural wiring pumps on this...

If there are qualia, they are even less accessible to our ken than we had thought. Not only are the classical intersubjective comparisons impossible (as the Brainstorm machine shows), but we cannot tell in our own cases whether our qualia have been inverted--at least not by introspection.

Actual psychopathologies can even confirm this.

Train's pulling in to my station....perhaps more later -

RogueAI

3.5kI don't think even Dennett knows his position anymore. I go over this with my 6th graders. Kids like metaphysics and ethics. They're not good at it, but they like talking about it. I wrote it out:

RogueAI

3.5kI don't think even Dennett knows his position anymore. I go over this with my 6th graders. Kids like metaphysics and ethics. They're not good at it, but they like talking about it. I wrote it out:

1. Stuff exists that isn't conscious and can't feel anything: atoms, rocks, comets, dirt, etc.

2. When you take some of this stuff and make a brain out of it, and add a little electricity, the brain becomes conscious.

3. How does the brain become conscious?

And I ask them to give me an explanation. After we go over their explanations, they want to know the real answer. I don't blame them. I think materialism's inability to answer it is catastrophic to the theory, but that's just me. -

fdrake

7.2kA property of your entire life and the environment you've interacted with up to this point, maybe, but that's definitely not on table. — Isaac

fdrake

7.2kA property of your entire life and the environment you've interacted with up to this point, maybe, but that's definitely not on table. — Isaac

@Kenosha Kid too, as this post is talking about problems with the qualia concept, previous post I made that this post is elaborating upon.

The impulse towards treating the sweetness as higher order predicates could already be wrong on Dennett's terms though, I'm unsure whether it would qualify as treating sweetness as a property held by an entity. I believe there is a possible tension there, depending on whether treating the experience as a greater than unary predicate in any sense commits the same "residual property" error that Dennett is alleging. The possible tension comes from:

He is on quite firm ground, epistemically, when he reports that the relation between his coffee-sipping activity and his judging activity has changed. Recall that this is the factor that Chase and Sanborn have in common: they used to like Maxwell House; now they don't. But unless he carries out on himself the sorts of tests others might carry out on him, his convictions about what has stayed constant (or nearly so) and what has shifted must be sheer guessing.

If I'm devil's advocating it; if the error arises ultimately from treating experience as an entity which bears properties, how is it any better to treat it as an entity which bears relations (or other high order predicates)?

A possible rejoinder may be the claim that the perceptual relation is not between an experiential entity and an object, the relation is of x experiencing y. Dennett need not treat a perceptual event as an experiential entity which bears properties or relations, it instead may be thought that the perceptual event is that higher order predicate. IE, the experience itself is a relation or higher order predicate ranging over a huge parameter space/domain. Rather than an entity which goes into such a relation as a term/function argument - like seeing a red quale - or outputs from such a relation as if evaluating experience as function - like "i see the result of my seeing".

Contrast "I perceived (the content of my perception ( of x ) )" and "I perceived x". The first has me entering into a relationship with the experiential entity of the content of my perception of x, and the second is that I enter into a relationship with x. In the second, there's no experiential entity that I enter into a relationship with, I simply perceive some stimulus of perception. "I experienced a red quale" has me entering into relationship with an experiential entity, "I experienced a red car" has me, well, experiencing a red car. A quale parsing of it - seeing ( red ( car ) ), and a non-quale parsing of it - seeing ( red car ). I see the red on the car vs I see the red car.

There's a whole lot of ambiguity in that parsing though, as that non-quale parsing has "red" inside of what's seen, in that red functions as part of a perceptual stimulus as well as being in the percept, maybe - then we've got the realism vs anti-realism of perceptual features debate again. I imagine that if we're talking about perceptual feature construction we're already quite far from the paper and qualia, though. So I want to pre-emptively nip that in the bud.

The salient point in the devil's advocate is that the "fundamental error" seems to be claiming that or acting as if we experience experiential entities (which have or may be experiential properties), rather than experience itself being a mode of our interaction with entities.

That looks to me one way of fleshing out it being okay to say "The coffee tasted sweet today" but not "My subjective experience of today's coffee was partially constituted by a quale of sweetness". -

Banno

30.6k"Red" is qualia no? — khaled

Banno

30.6k"Red" is qualia no? — khaled

Well, that's the question. If that's all they are, why introduce the term? Those who use the term might speak of "What it is like to see red", not of "red" as such. Qualia seem to want to do more than is done by words like "red". See for instance the first paragraph of the SEP article....

But how is "What it is like to see red" distinct from "Seeing red"? -

Olivier5

6.2kTo perhaps illustrate it further: if we allow ourselves to do the usual thing we do, like go from: (1) "The coffee I had today tasted sweet to me" to (2) "The sweetness of the coffee I had today" to (3) "My subjective experience of sweetness from the coffee I had today", we actually describe the experience with different logical structures. — fdrakeIt's pretty clear that these don't mean the same thing; (1) is a relationship between object level entities in a domain (me, coffee), (2) is a relationship between an object level entity in a domain and a property defined over some unspecified domain (me, coffee property) and (3) a relationship between a property of me and an object of the domain (property of me, coffee). — fdrake

Olivier5

6.2kTo perhaps illustrate it further: if we allow ourselves to do the usual thing we do, like go from: (1) "The coffee I had today tasted sweet to me" to (2) "The sweetness of the coffee I had today" to (3) "My subjective experience of sweetness from the coffee I had today", we actually describe the experience with different logical structures. — fdrakeIt's pretty clear that these don't mean the same thing; (1) is a relationship between object level entities in a domain (me, coffee), (2) is a relationship between an object level entity in a domain and a property defined over some unspecified domain (me, coffee property) and (3) a relationship between a property of me and an object of the domain (property of me, coffee). — fdrake

There's no real difference between the three, it's all a language trick. Expression 1 sounds objective but what does "tasted sweet" mean, if not some relation between the coffee and you (as in 2), and what is this relation, if not a sensation, the "sugar quale"? And what does "to me" mean, if not "in my mind"?

Note that:

A. You could objectively and scientifically measure the concentration of a specific sugar (in this case saccharose) in your coffee, verifiably so.

B. You can somehow perceive this concentration of sugar by tasting your coffee, and you are (I trust) able to sense if there is too little, enough or too much sugar for your personal taste. Your subjective assessment is probably going to align decently well with an objective measurement mentioned in A. This means that your 'perception' (or 'percepting' or 'sensation' or 'quale' or whatever you want to call it) is quantitative, and not just qualitative.

C. The taste of sugar is described almost universally as quite distinct from others, such as the taste of salt, and generally pleasurable within limits. This is probably related to its survival advantage (sugar is energy) and to the fact that our tongue includes taste receptors demonstrably able to sense five taste modalities: sweetness, sourness, saltiness, bitterness, and savoriness (also known as savory or umami).

All this indicates that there is such a thing as the taste of sugar. -

fdrake

7.2kThere's no real difference between the three, it's all a language trick. — Olivier5

fdrake

7.2kThere's no real difference between the three, it's all a language trick. — Olivier5

The difference between a property of an object and an object is pretty big. "3 is prime" says the property "is prime" applies to 3, whereas "is prime" isn't even a number. What's the square root of the concept of prime? The answer is nonsense. -

Olivier5

6.2kThe difference between a property of an object and an object is pretty big. " — fdrake

Olivier5

6.2kThe difference between a property of an object and an object is pretty big. " — fdrake

Not sure what you mean here. To taste sweet is an objective property of sugar? Not really. When you say"The sweetness of the coffee I had today", it's not about a coffee you didn't taste, is it? You had it. -

Kenosha Kid

3.2k[Off-topic post, moved to different thread.] — Kenosha Kid

Kenosha Kid

3.2k[Off-topic post, moved to different thread.] — Kenosha Kid

I kind of panicked as my post wasn't at all driven by Quining Qualia itself. I should have just brought it back to the text.

Dennett's issue is not with the concept of qualia generally but with a particular definition of qualia, and I think his beef is not with the private or immediate aspects, but with ineffability and particularly the intrinsic aspect.

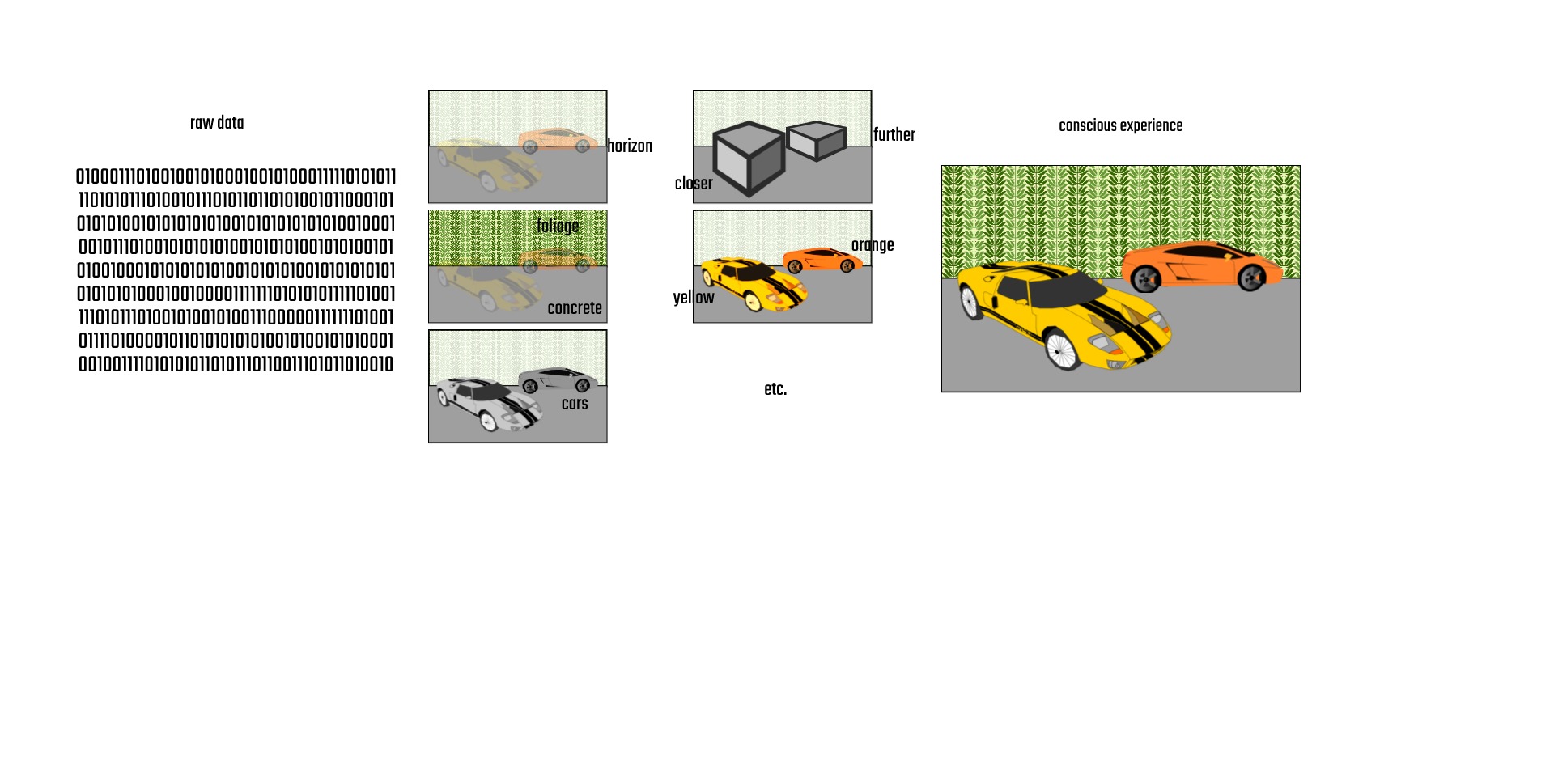

@Isaac above describes two example streams of unconscious processing of sensory data, one which pattern-recognises (the ventral) and one which contextualises (the dorsal). These might run in parallel, with the what-is-it part not aware or bothered by where-it-is, and the where-is-it part not aware or bothered by what-it-is.

(click to enlarge)

When I see the third image above, I see two cars, one to the left, one to the right, the left one closer, the right one further away, the left one yellow, the right one orange. All of this is immediately presented to me, by which I mean that, though I may determine these things over time as I focus on them, I do not have to consciously derive them by looking at them.

I think we can exclude the possibility that Dennett is unaware that raw sensory data (represented inaccurately as ones and zeros here) gets processed by the brain before it presents it to the consciousness (middle collection of images). And we can exclude the possibility that no such processing ever occurs. (As Isaac pointed out, the brain is good at identifying what is not worth presenting to our consciousnesses, like car engine sounds when you live in a flat in Manhattan.)

So Dennett is presumably okay with the fact that, consciously, I am immediately presented with a yellow car, for instance, not an indistinct image that I consciously have to decode, and that the transition from raw data to final perception is an internal -- i.e. private -- one.

His intuition pumps mostly revolve around connecting qualia over time or space. Is the yellow the same yellow I saw last night? Is the yellow the same yellow you see? Is it meaningful to even extract the yellow to compare? This is his issue with the intrinsic qualities of qualia: that you can meaningfully compare two. But this is not demanded by our conscious experiences. It is not our rational minds that generally determine that the car is the same colour as it was yesterday, rather the colour of the car is part of how we recognise it as ours.

He also dislikes the ineffability of qualia, that we cannot know our qualia better. But the above is a layperson's cartoon of how we can learn to know our qualia better in terms of whatever physical processes are occurring in between raw sensory data and perceived image. We can conceive of a Dennett's demon: an accounting for the history-dependent state of the subject plus a full knowledge of the input sensory data, plus a full understanding of the presumed deterministic process that the former enacts on the latter to produce an immediate world as presented to the consciousness.

We have to hear the filtered harmonic to hear it in the unfiltered 'note' (really a chord), but, once the brain is trained, it will present not a sole E to the ear but the higher E and other harmonics as well. Dennett's demon could account for this, could distinguish between an less well trained brain that presents the sound as best it can as a single note and one that has been trained to pick out the individual notes and present them all for conscious appraisal. The qualia then are different, and depend on what the brain does with the same raw sensory input. But we still hear the note(s), however they ended up. -

Olivier5

6.2kThen, I suppose, you don't subscribe to the five senses tradition. How many senses have you identified? — Merkwurdichliebe

Olivier5

6.2kThen, I suppose, you don't subscribe to the five senses tradition. How many senses have you identified? — Merkwurdichliebe

Seven, with the sense of equilibrium.Yes. To our own sensing, to our own perceiving, and to our own thinking. — Merkwurdichliebe

You access these (reflexively) through some sense, in my view, through self-awareness, rather than directly. -

Merkwurdichliebe

2.6kSeven, with the sense of equilibrium. — Olivier5

Merkwurdichliebe

2.6kSeven, with the sense of equilibrium. — Olivier5

Equilibrium as in physical, or mental balance? Do you correlate introspection/reflection and equilibrium with a particular organ (e.g. seeing with eyes or feeling with skin)?

You access these (reflexively) through some sense, in my view, through self-awareness, rather than directly. — Olivier5

That is where we differ. Self-awareness is immediacy itself, and not a faculty that mediates existence. Self awareness is what relates directly to its faculties of sensing, perceiving and thinking, and through them it relates indirectly to things that are sensed, perceived, and thought. Hence the inadequacy of self-awareness (as recognized by Nietzsche) - how much is there that we do not sense, percieve or think...infinitely more than we do. So much for the human endeavor for knowledge...luckily we can still seek self knowledge. -

fdrake

7.2kAll of this is immediately presented to me, by which I mean that, though I may determine these things over time as I focus on them, I do not have to consciously derive them by looking at them. — Kenosha Kid

fdrake

7.2kAll of this is immediately presented to me, by which I mean that, though I may determine these things over time as I focus on them, I do not have to consciously derive them by looking at them. — Kenosha Kid

I think you're pretty off the mark here exegetically @Kenosha Kid,

(1) ineffable (2) intrinsic (3) private (4) directly or immediately apprehensible in consciousness Thus are qualia introduced onto the philosophical stage. They have seemed to be very significant properties to some theorists because they have seemed to provide an insurmountable and unavoidable stumbling block to functionalism, or more broadly, to materialism, or more broadly still, to any purely "third-person" objective viewpoint or approach to the world (Nagel, 1986). Theorists of the contrary persuasion have patiently and ingeniously knocked down all the arguments, and said most of the right things, but they have made a tactical error, I am claiming, of saying in one way or another: "We theorists can handle those qualia you talk about just fine; we will show that you are just slightly in error about the nature of qualia." What they ought to have said is: "What qualia?"

If you are wondering about something which may be or fail to be "immediate", "intrinsic", "priviate" or "ineffable", I think Dennett would say you've already gone too far. What qualia?

My claim, then, is not just that the various technical or theoretical concepts of qualia are vague or equivocal, but that the source concept, the "pretheoretical" notion of which the former are presumed to be refinements, is so thoroughly confused that even if we undertook to salvage some "lowest common denominator" from the theoreticians' proposals, any acceptable version would have to be so radically unlike the ill-formed notions that are commonly appealed to that it would be tactically obtuse--not to say Pickwickian--to cling to the term. Far better, tactically, to declare that there simply are no qualia at all. Endnote 2

In the opening paragraph, Dennett wondered how another person could relish the taste of cauliflower when he himself hates it. If a person goes from such an observation to asserting the existence of a taste quale which varies over people, Dennett already asserts that that person has made a "fundamental mistake":

This "conclusion" seems innocent, but right here we have already made the big mistake. The final step presumes that we can isolate the qualia from everything else that is going on--at least in principle or for the sake of argument. What counts as the way the juice tastes to x can be distinguished, one supposes, from what is a mere accompaniment, contributory cause, or byproduct of this "central" way. One dimly imagines taking such cases and stripping them down gradually to the essentials, leaving their common residuum, the way things look, sound, feel, taste, smell to various individuals at various times, independently of how those individuals are stimulated or non- perceptually affected, and independently of how they are subsequently disposed to behave or believe. The mistake is not in supposing that we can in practice ever or always perform this act of purification with certainty, but the more fundamental mistake of supposing that there is such a residual property to take seriously, however uncertain our actual attempts at isolation of instances might be.

I think the paper's a battle on all fronts; against qualia existence claims, against their typically ascribed first order properties (the creamy cauliflower taste quale), against their second order properties like ineffability (the ineffability of the creamy cauliflower taste quale). -

Merkwurdichliebe

2.6kI think the paper's a battle on all fronts — fdrake

Merkwurdichliebe

2.6kI think the paper's a battle on all fronts — fdrake

That is a lot of work simply to discredit an already lame term that nobody ever uses, not even the lamest philosophers (I should know, I have an army of lame philosophers following me here at TPF, spewing the lamest shit ever passed off as philosophy). My sincerest aplopogees. -

magritte

596

magritte

596

any acceptable version would have to be so radically unlike the ill-formed notions that are commonly appealed to that it would be tactically obtuse--not to say Pickwickian — Dennett

So, Dennett is not saying that metaphysical objects somewhat like qualia are impossible, but that the terminology used would need to be something unfamiliar. Not even necessarily novel, just unusual.

The cauliflower case is directly out of Heraclitus, label it 'relational' if you like. The problem is old, the solution is nowhere in sight.

Qualia are a valiant attempt to bridge the gap between subjective phenomenal experience and objective philosophy. If qualia cannot be fixed objects, then how can we communicate thought, feelings, and sensations in the language of philosophy? -

Merkwurdichliebe

2.6kThe cauliflower case is directly out of Heraclitus, label it 'relational' if you like. The problem is old, the solution is nowhere in sight. — magritte

Merkwurdichliebe

2.6kThe cauliflower case is directly out of Heraclitus, label it 'relational' if you like. The problem is old, the solution is nowhere in sight. — magritte

Please post this on every thread -

Luke

2.7kI think the paper's a battle on all fronts; against qualia existence claims, against their typically ascribed first order properties (the creamy cauliflower taste quale), against their second order properties like ineffability (the ineffability of the creamy cauliflower taste quale). — fdrake

Luke

2.7kI think the paper's a battle on all fronts; against qualia existence claims, against their typically ascribed first order properties (the creamy cauliflower taste quale), against their second order properties like ineffability (the ineffability of the creamy cauliflower taste quale). — fdrake

How does the first-order property (the creamy cauliflower taste) differ from the sense datum (taste)? You previously stated that the denial of qualia did not necessarily imply the denial of sense data.

How is this consistent with Dennett’s claimed acknowledgement that conscious experience has properties?

"Qualia" is an unfamiliar term for something that could not be more familiar to each of us: the ways things seem to us. As is so often the case with philosophical jargon, it is easier to give examples than to give a definition of the term. Look at a glass of milk at sunset; the way it looks to you--the particular, personal, subjective visual quality of the glass of milk is the quale of your visual experience at the moment. The way the milk tastes to you then is another, gustatory quale, and how it sounds to you as you swallow is an auditory quale; These various "properties of conscious experience" are prime examples of qualia. -

Merkwurdichliebe

2.6kthe ways things seem to us — Luke

Merkwurdichliebe

2.6kthe ways things seem to us — Luke

gustatory quale

Gustatory? Seriously? How are you going to talk about "the ways things seem to us" by introducing terms like "gustatory quale"? Fuck "masturbation", more like "rectal bombarbment"!

I have other meaningless bullshit terms that we can make up shit about: "god, subject/object, soul, existence &c. -

Luke

2.7kGustatory? Seriously? How are you going to talk about "the ways things seem to us" by introducing terms like "gustatory quale"? — Merkwurdichliebe

Luke

2.7kGustatory? Seriously? How are you going to talk about "the ways things seem to us" by introducing terms like "gustatory quale"? — Merkwurdichliebe

It’s the opening paragraph of the article - Dennett’s words, not mine. But go off.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum