-

Antony Nickles

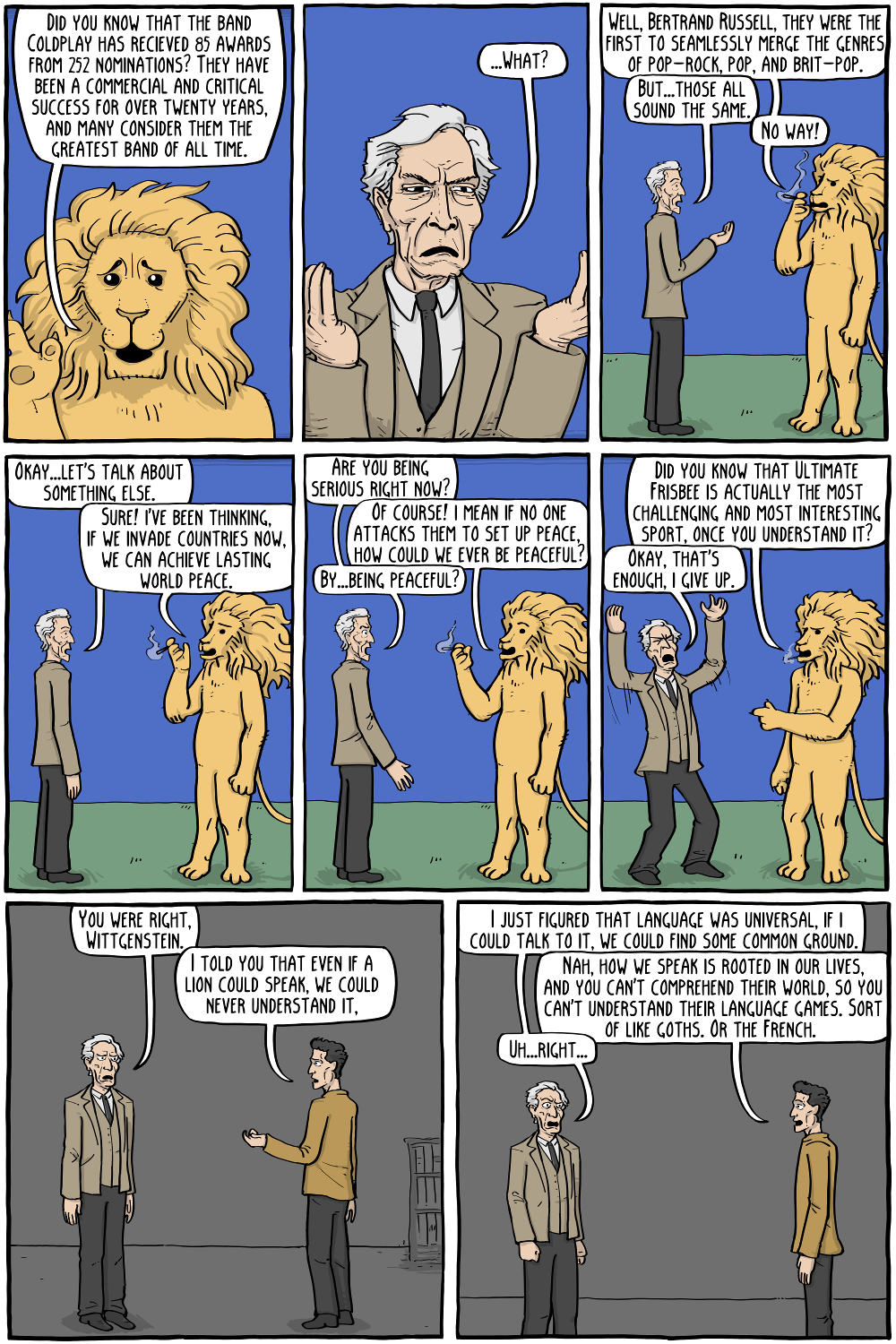

1.4k"If a lion could talk, we could not understand him." Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations pg 223 (3rd Ed., 1968) “PI”

Antony Nickles

1.4k"If a lion could talk, we could not understand him." Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations pg 223 (3rd Ed., 1968) “PI”

Attempting to show Wittgenstein ("Witt") is making an ethical argument (through unearthing the desires of positivism) in the Philosophical Investigations, I will argue that it is essential to put the above sentence in the textual context in which it was written to see its USE here--the sense ("Grammatically") in which it is said (“meaning” not existing independently, beforehand, immediately, certainly, etc.)--in its sense as an uncontested FACT (not to be refuted or interpreted, nor an open question, nor a thesis, etc.). This is a close reading and, with hope, a demonstration of Ordinary Language Philosophy (people may call this "Philosophy of Language", but that term is misleading as it takes a position on morals/ethics, epistemology, logic, science, the mind, metaphysics, etc.)

Note: The page (223) of the PI is transcribed at the end of this post, and I encourage you to read it thoroughly before reflexively posting an opinion on just this one sentence as if it were an solitary tclaim of Witt's which is open to question. So, you may have another interest in this sentence--and in philosophy--(which is fine), but, if you take the trouble to respond, I ask please that you here indulge me and start by trying to see the angle to the text which I am proposing; otherwise, I welcome any additional thoughts on the rest of the text as well. (Also, all phrases below in “quotes” are from page 223 unless otherwise noted; all emphasis in italics are in the original work; all my emphasis on terms is done in ‘ single-quotes ’ or all CAPS.)

Another reader offered this:

“My guess is that what is meant here is that we have no basis for understanding because our context of 'understanding' is so radically different than that of a different species.”

Setting aside for now (see *** below) the imagining of the difference in the internal (external) world of a lion (I’m going to jump around in the text a bit), the comment assumes there is a “context of understanding” which is the "basis" of " ‘understanding’ ". But what is Witt actually getting at? If we are to begin with “contexts of 'understanding' ”, it sounds very similar to the people with “strange traditions” mentioned at the top of the page.

We also say of some people that they are transparent to us. It is, however, important as regards this observation that one human being can be a complete enigma to another. We learn this when we come into a strange country with entirely strange traditions; and, what is more, even given a mastery of the country's language. We do not understand the people. (And not because of not knowing what they are saying to themselves.) We cannot find our feet with them. — Witt, PI p. 223

Here, in this situation, we can communicate. But we do not understand the 'people', say, as our people; we do not understand their judgments, criteria, manners, expectations, consequences, etc. They are an "enigma" to us; not so much hidden, as a mystery. We “cannot find our feet” with them; we would have to learn their judgments, criteria, manners, expectations, consequences, and align/differentiate the differences from ours.

Now a lot of people stop with Wittgenstein at this point, and take him as just having the opinion that his term 'Forms of Life' (these traditions) gives meaning to words allowing for communication and thus knowledge of traditions are all we need for understanding--they (similar reactions, communal agreement, etc.) are the "basis".

The motivation for this misappropriation is much the same for what Witt addresses next: which is when people think internal ideas or other thought processes ('meanings') are connected to the world/words, which allows for (are the "basis" for") communication. This is the misconception Witt starts with at the top of the page, which begins:

'What is internal is hidden from us'. — Witt, PI p. 223

[ read this as if it were stated TO Witt (not by him) by someone else, commonly referred to as, the “Interlocutor” ]

If I see someone is writhing in pain with evident cause, I do not think: all the same, his feelings are hidden from me. — Witt, PI p. 223

[ Here, this is Witt’s voice ]

If their feelings are apparent ("evident"), “I do not think: [that they] are hidden”. This begs the question then, what do I think? Is this then a person whom we would say is “transparent to us”? When we know their Forms of Life, is everyone? Maybe this isn't just a philosophical disagreement about whether "meaning" is internal or external. Then, why do we desire to put up a barrier to the ("hidden") other?

This is where I think it is very important—essential—to see that the lion-quote puts a perspective on the quote just above it, which is:

'I cannot know what is going on in him' is above all a picture. It is the convincing expression of a conviction. It does not give the reasons for the conviction. They are not readily accessible.

If a lion could talk, we could not understand him. — Witt, PI p. 223

I strongly impress upon you to find a way to see that the "cannot" in the first sentence, is in contrast to the "could not" in the lion sentence.

As in (placing the phrasing in parallel structure): 'Now HERE [with the lion] we COULD NOT understand him'--as in, it is impossible, a fact (said as uncontested--see ** below)--but, with the person saying they 'CANNOT know' another person, it is a conviction--a decision or firm belief. [The ’quotes’ are only a re-phrasing of Witt.]

This use of the lion-quote is comparison; not as a hypothesis, not an opinion or belief, not to be considered, but as an uncontested fact**--'grammatically' as one, Witt would say, and also: Look at the use!! (#66) This use is not to inspire debate (even though it could--that is one of its possibilities; but not here, in this context). Wittgenstein is not making a 'claim' to “very general facts of nature (Such facts as mostly do not strike us because of their generality)” p. 56, #143. The use of these facts is as contrast “to explain the significance, I mean the importance, of a concept,” (ibid.) like, here, with 'understanding' (see also the dog, p. 229, or the parrot, #346).

Clarification: Witt's focus on "use" has been a stumbling block in the responses, so I wanted to point out that it is not the idea that use (some internal force/decision) determines or is the basis for "meaning". There are multiple versions ("senses") of a concept; one determines the use from the context (afterwards). "Every word has a different character in a different context." PI, p. 181. Not to say a we do not sometimes chose what we say, but senses exist outside and prior to us; the same confusion is that every word/action is 'intended'. The idea of a sentence or a word in isolation is only a thing in some philosophy--stemming from the desire to tether it to something determinate, certain, universal. Nietzsche also is taken to be claiming statements about society--say, in Human, All to Human’s chapter “Man in Society” rather than just using them as examples/contrasts to shed light on our moral process.

And so (as opposed to with the lion) we CAN know what is “going on in him” (though see *** below), and saying we cannot is a conviction, a belief (in this example, in a particular theoretical framework/"picture"; roughly, that meaning is tied to an idea). Apart from just the conviction in the picture though, Witt is making a point that we are responsible in how we treat the other. It is an ethical argument, not (merely) an epistemological one. The conviction is a person's choice not to ACCEPT what is going on with/in the other, as opposed to how it would be with the lion, where we simply CANNOT understand there (again, look at it as a fact--in its fact-ness--compared to the choice we are making with the other).

The example is similar to the student in #144; "I wanted to put that picture before him, and his 'acceptance' of the picture consists in his now being inclined to regard a given case differently"--we are in a position to reject or accept. This is a decision, a choice. With the person in pain we are in a position (“being inclined” #144) to regard (accept) something as such; "My attitude towards [them] is an attitude towards a soul. I am not of the 'opinion' that [they have] a soul." p. 178. We don't have knowledge that they have a soul, we treat them as if they do.

If I see someone is writhing in pain with evident cause, I do not think: all the same, his feelings are hidden from me. — Witt, PI p. 223

We do not “think” in this sense, because our understanding of the other is not a matter of knowledge. If someone is expressing pain, you acknowledge (react to) the person or you deny them (from Cavell). It is not our intellect that is limited--that we lack some knowledge (of a form of life) or access (to the other's private thoughts). Replying to the sceptic that says, "I cannot know what is going on in [them]", that they are mistaken—you CAN know!—is simply to miss the point.

If someone is writhing in pain, we do not think: 'the picture is wrong' (does not reflect reality) or that 'sensations ARE evident' (just, to science). The (positivist) picture is an expression of a conviction to ignore the moral claim the other's pain makes on me—their humanity—to disavow our responsibility for the other, the meaningfulness of their expressions (to look past the other for something certain, infallible). If I am convinced (by positivism's picture, or by a choice about the other), in this sense I "am certain" and "[my eyes] are shut” [to their pain] (just after on p. 224). We have stopped being understanding. There is nothing else to SEE (no form of life to learn or share), no knowledge to gain that will necessarily change my conviction about/relationship to, the other.

The reasons for the conviction (to deny the other) are "not readily accessible", because it is not the picture that gives them (not science nor positivism nor behavioralism); it is the person (justifying, apologizing, standing on principal, or without reason, etc.). The reasons for refusing to see the other's pain are accessible, but we must ASK the person rather than just have knowledge of their Form of Life, or the contents of their brain. To mean (or not) what you say and do is not a thing, it is a position (Witt calls it an attitude); reason is not an ability--people have reasons (or don’t) for speaking or acting. What they meant (their rationale) does not (usually) come up unless someone asks (‘Why did you… ?’ ). Their reasons are not private nor public so much as personal, say, a secret (Cavell, again). This creates the possibility of a lie, and the fear of it; and this doubt is the desire to “guess thoughts”. Witt isn’t stating facts or arguing theories about lions or our brains or our lives; he is investigating (not solving) that fear.

***Now to get back to the lion (and its insides) that everyone is dying to conjecture and hypothesize about; some will balk at limiting it to a logically-contrasted fact, or maybe even more at Witt's point: that neither science, nor its philosophically-clothed cousins--positivism, emotivism, behavioralism, etc.--are able to access or address the basis of understanding (with A.I., our individual internal experience, ‘qualia’, Forms of Life, agreement, etc.). Science can describe forms of life, explain pain, but a conceptual investigation (the criteria for the Grammar (workings) of pain, knowledge, etc.) tells us about our convictions (“Concepts lead us to make investigations; are the expression of our interest, and direct our interest.” #570). How the concept of pain works (our judgments surrounding it, the consequences from it, the structure of our relationship to it, etc.) is the expression of our interest in pain--why we care about it, how it matters to us; e.g., how we are defined by our reaction to it. Those mixing science and philosophy read the lion-quote (and philosophy generally) to use for their interests; unrelated, motivated by a particular outcome, etc.

QUOTED FROM: Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations uninterrupted excerpt from p. 223 (3rd Ed., '68)

* * *

There is a game of 'guessing thoughts'. A variant of it would be this: I tell A something in a language that B does not understand. B is supposed to guess the meaning of what I say.-Another variant: I write down a sentence which the other person cannot see. He has to guess the words or their sense.--Yet another: I am putting a jig-saw puzzle together; the other person cannot see me but from time to time guesses my thoughts and utters them. He says, for instance, "Now where is this bit?"--"Now I know how it fits 1"--"I have no idea what goes in here,"--"The sky is always the hardest part" and so on--but I need not be talking to myself either out loud or silently at the time.

All this would be guessing at thoughts; and the fact that it does not actually happen does not make thought any more hidden than the unperceived physical proceedings.

"What is internal is hidden from us."--The future is hidden from us. But does the astronomer think like this when he calculates an eclipse of the sun?

If I see someone writhing in pain with evident cause I do not think: all the same, his feelings are hidden from me.

We also say of some people that they are transparent to us. It is, however, important as regards this observation that one human being can be a complete enigma to another. We learn this when we come into a strange country with entirely strange traditions; and, what is more, even given a mastery of the country's language. We do not understand the people. (And not because of not knowing what they are saying to themselves.) We cannot find our feet with them.

"I cannot know what is going on in him" is above all a picture. It is the convincing expression of a conviction. It does not give the reasons for the conviction. They are not readily accessible.

If a lion could talk, we could not understand him.

It is possible to imagine a guessing of intentions like the guessing of thoughts, but also a guessing of what someone is actually going to do.

To say "He alone can know what he intends" is nonsense: to say "He alone can know what he will do", wrong. * * *

[Antony Nickles: and to provide the full quote from p. 56 (right after #143): "What we have to mention in order to explain the significance, I mean the importance, of a concept, are often extremely general facts of nature: as are hardly ever mentioned because of their great generality."] -

Daemon

591I will argue that it is essential to put this sentence in the context in which it was written to see what makes it meaningful ( — Antony Nickles

Daemon

591I will argue that it is essential to put this sentence in the context in which it was written to see what makes it meaningful ( — Antony Nickles

I'm willing to try to understand your point. Is the above your point? -

Antony Nickles

1.4kYou may be right that the sentence needs to be read in context, but I don't understand the context. — Daemon

Antony Nickles

1.4kYou may be right that the sentence needs to be read in context, but I don't understand the context. — Daemon

By context, I mean the textual context--its use in relation to the rest of the language around it. -

Mww

5.4kAll taken from the quoted passage:

Mww

5.4kAll taken from the quoted passage:

Thesis:

All this would be guessing at thoughts; and the fact that it does not actually happen does not make thought any more hidden than the unperceived physical proceedings. — Antony Nickles

Antithesis:

What does not actually happen? I ask a guy to assign meaning to a language he doesn’t understand mandates a mutually perceived physical proceeding.....I’m talking to him, after all, and I know he hears me. So this cannot be the thing that does not actually happen. The only thing left that does not actually happen, and is therefore the unperceived physical proceeding, is the objective exemplification by which meaning is assigned by the dude to whom I’m asking. All that reduces to a categorical error of modality, the schema of which is existence, to posit that which doesn’t happen is equal to being hidden. There is nothing to hide so it being hidden is superfluous.

Still, it must be the case that he thinks something, even if it’s only to think it impossible to give any meaning because he lacks the judgements necessary to connect what he perceives to what he understands. The unperceived physical proceeding, in this case speech reflecting the assignment of meaning, according to W, is hidden from both of us because it never happened, but the thought demonstrating that the meaning is impossible to present as a physical proceeding, must have happened, and is only hidden from me, to whom it did not happen, but cannot be hidden from the guy from whom I’m asking a meaning be given. This is the categorical error of relation, the schema of which is community, in that it is supposed one thought is denied to, or hidden from, both parties when it is only hidden from one.

—————-

Thesis:

If I see someone writhing in pain with evident cause I do not think: all the same, his feelings are hidden from me. — Antony Nickles

Antithesis:

No, I do not, but I do not, because I think nothing immediately with respect to his feelings, as a predicate of my observation of him writhing. Given the evident cause, I immediately grant him the objective reality of being hurt, the writhing I see immediately grants merely one of a plethora of immediate corresponding physical representations of being physically hurt, both of which are a posteriori judgements.

I can and I do think, mediately, all the same, his feelings are necessarily hidden from me, in that the causality of his representations are not contained in the physical representations of them. And I am justified in that thinking, for the simple reason I am not the one writhing with evident cause. If I already understand feelings as pure a priori representations, and I know no a priori cognition is transferable, it follows as a matter of course, his pain is inaccessible to me, hence I am permitted to say they are hidden. This, incidentally, relieves the categorical error of modality.

—————

Thesis:

"I cannot know what is going on in him" is above all a picture. It is the convincing expression of a conviction. It does not give the reasons for the conviction. They are not readily accessible. — Antony Nickles

Antithesis:

If I know, or if I do not know, something, I must have reasons. And they must be accessible to me, otherwise the knowledge is quite empty.

Knowledge can be defined as a judgement valid because its ground is objectively necessary. That which goes on in him is subjective in him, hence inaccessible objectively in me, therefore I am justified in claiming I cannot know of it. These are my readily accessible reasons derivable from a definition.

A conviction can be defined as a judgement valid because its ground is objectively sufficient. I am certainly authorized to say what goes on in him is objectively sufficient, under the condition that he and I are both the same kind of rational intelligence, in that I allow him the same ground for his as I require for mine.

It follows that what I know is not the same as that of which I am merely convinced. I am always authorized to claim my convictions are given from the same reasons as my knowledge, but I am not authorized to claim my knowledge is given from the same reasons as my convictions.

A picture, considered as some mental image, can be a convincing expression of a conviction, but not in the case where I have certain knowledge antecedent to the image. While it is true images are not the source of reasons in any case, where some proposition is predicated on a knowledge, those reasons are not needed, so their inaccessibility is moot. I need reasons for my convictions iff I cannot arrive at knowledge from conviction alone.

The lion will have to wait for Page 2, assuming there is one.

Thanks for the interesting thread, and the chance to ramble on over it. Hope I followed your wishes, but if I didn’t.....ehhhh.....no page 2. -

Daemon

591Hi Antony, I've given it my best shot and got nowhere really. I respect your wish to have a particular kind of discussion, so I'm going to express my views about Wittgenstein in a new thread.

Daemon

591Hi Antony, I've given it my best shot and got nowhere really. I respect your wish to have a particular kind of discussion, so I'm going to express my views about Wittgenstein in a new thread. -

Antony Nickles

1.4k

Antony Nickles

1.4k

Note: In responding, I want to point out that all the quotes being responded to are Wittgenstein’s (not mine)—I'll underline those; and use quotes from Mmw’s response. Also, labeling Witt’s sentences as “Thesis” is not exactly accurate. These are not claims to true statements (similar to the point I’m making about the lion-quote). He is not advancing a theory. He is trying to get us to change our perspective on an historical philosophical picture, imagine a different view of our terms and beliefs and framework (paradigm Kuhn might say).

"Thesis:"

All this would be guessing at thoughts; and the fact that it does not actually happen does not make thought any more hidden than the unperceived physical proceedings.

Antithesis: What does not actually happen? — Mww

As a Ordinary Language Philosopher, Witt creates imagined scenarios to flesh out the consequences of people’s beliefs (here, roughly, the belief in something internal connected to words as meaning). In this case, the examples above this quote, of guessing at thoughts, are the situations or circumstances that may not actually happen in ordinary life.

I ask a guy to assign meaning to a language he doesn’t understand mandates a mutually perceived physical proceeding… There is nothing to hide so it being hidden is superfluous. — Mww

The “unperceived physical proceedings” are the writing and the jig-saw puzzles, etc.—which are hidden in the sense of, away from view. The point is those are analogous to the confused picture of something hidden, internally, “Qualia”, meaning, some mental occurrence. This is not to say people are see-through (it can be hidden privately, as I’ve said). I think maybe having decided a picture/theory/belief already, may be getting in the way of understanding the terms (words) and how Witt is relating them to each other in the different paragraphs, which do not stand alone.

Still, it must be the case that he [the other whose thoughts we are trying to guess] thinks something — Mww

No; it’s not the case (do you always think? do you always think before you speak?). Witt’s point is ‘thinking’ in the sense I believe you are using it (that it is (always) connected to speaking; as ’meaning’ is believed to be connected to words, like a definition) is a picture created from a desire to force the issue, as I discussed in the post. One confusion is maybe the belief that ’thinking’ can only be meant one way; consider: deliberating, reflecting, imagining, formulating, etc. And how words work is not for us to “assign” (usually), say internally. Try to compare pre-determined ‘meaning’ to asking someone after they have said something, “What did you mean?” or someone saying, “I didn’t mean that I was thinking about it in that I hadn’t made a decision, I was just considering your feelings first”. Examine in the text how he points out that I could tell what you intended (‘mean’) before you do (see below)—and this is not to read your mind or guess some ever-present thoughts (or physical situation) connected to your actions and speech.

…the thought… must have happened, and is only hidden from me, to whom it did not happen, but cannot be hidden from the guy from whom I’m asking a meaning be given. — Mww

Again, the idea is not an internal occurrence. If you change the picture of thinking, we can know what someone is thinking, for example, as intending: (“she’s going to eat that donut”), even when the person is blind to it themselves (“she says she’s not an alcoholic, but she’s going to drink again”). Ordinary Language Philosophy, like Witt, is about unpacking these words philosophers use (‘knowledge’ ‘thinking’ ‘meaning’) to see them in an ordinary context, and the variety in sense they have, in order to examine the motivations for pushing them into the boxes philosophy has historically.

—————-

"Thesis:"

If I see someone writhing in pain with evident cause I do not think: all the same, his feelings are hidden from me.

Given the evident cause, I immediately grant him the objective reality of being hurt — Mww

I think you’re on the right track with the rest of what you wrote; Witt’s immediate point is: why would we start with doubt backed up by a picture of some hidden occurrence? but the further point, I discuss in the post, is that we do not have to grant the other their pain—we can ignore the person on the street; treat a slave as less than human, etc. The “a posteriori judgement” is not immediate or given, say, apart from us (maybe let go of “objective” and “real”).

I can and I do think, mediately, all the same, his feelings are necessarily hidden from me, in that the causality of his representations are not contained in the physical representations of them. — Mww

The idea of causality is part of the picture of meaning being taken apart here. Is it continual? ever-present? always accessible? There could be no ‘cause’ nor any ‘pain’; he could be faking, acting, etc. And, oppositely, why can’t the “cause of his representations” be contained in the physical? “He is in pain—it looks like a heart attack.” “He’s not in pain—that scream is too forced to be real.” And if I understand what you mean by “error of modality”, things like intention, attitude, etc. are ordinarily discussed after the fact, rather than always determined prior to an act; and, as the general theme of the PI, the modalities (“grammar” he says) are different for every type of action. Maybe I have those terms wrong of course; not my specialty.

—————

"Thesis:"

"I cannot know what is going on in him" is above all a picture. It is the convincing expression of a conviction. It does not give the reasons for the conviction. They are not readily accessible.

Antithesis:

If I know, or if I do not know, something, I must have reasons. And they must be accessible to me, otherwise the knowledge is quite empty. — Mww

Again, take a look at re-thinking ‘know’ and ‘reason’. If you know something it might make sense to ask HOW you know, or maybe in what way you know something, but would it (always?) make sense to ask what my ‘reason’ is for knowing something? maybe “I know what year I was married because it’s my password.” but ,e.g., “No reason; I must have heard it somewhere.” But is that knowledge “empty”? To me it is nothing, but maybe to the other person it is the answer to the crossword they were killing themselves for.

Knowledge can be defined as a judgement valid because its ground is objectively necessary. That which goes on in him is subjective in him, hence inaccessible objectively in me, therefore I am justified in claiming I cannot know of it. These are my readily accessible reasons derivable from a definition. — Mww

Knowledge could be defined like that, but it is not its only sense; “I’m in pain!” “Okay, okay! I know you’re in pain. Just wait, I have to get the top off this Tylenol.” This is an acknowledgment that the other person is in pain (“I [am acknowledging] you’re in pain”). Scientific knowledge can be facts (grounded in method); knowledge can be skill (“I know how to take apart a Chevy engine.”), etc. And it is the reasons for the decision not to know their pain that are not accessible, but, importantly, “readily”, say, without asking. We may be a psychopath, we may have seen them suffer so much we are numb, etc. The reason for the “picture” is that positivism wants to secure knowledge of the other, or deny its possibility, in order to avoid our responsibility for them, answer to/for them.

A conviction can be defined as a judgement valid because its ground is objectively sufficient. I am certainly authorized to say what goes on in him is objectively sufficient, under the condition that he and I are both the same kind of rational intelligence, in that I allow him the same ground for his as I require for mine.* * * “I need reasons for my convictions if I cannot arrive at knowledge from conviction alone. — Mww

My understanding is a conviction is just another word for belief, although “strongly held”; one way to see it might be that we have to stand for our beliefs, where knowledge can be said to be apart from our relationship to it. “I hold the belief you’re not in pain strongly, against any attempt to plead with me to see it.” or “I didn’t know he was in pain, there was no evidence.” And if you don’t have an ‘objectively sufficient judgment’, can you not know their pain? (Sympathize with it, recognize it, etc.) Witt might say the belief (conviction) in your criteria of reason shuts your eyes to seeing a wider world. That belief is a “convincing picture” because it preys on our doubt and our desire to avoid the other (and ourselves), say, behind objective rationality.

And, yes, I would suggest reading the text as one piece rather than singular statements (to be refuted), and I hope that my post is worth more than just anti-thesis. -

Antony Nickles

1.4k(I hadn't "replied" to your post, so you may not have seen this)

Antony Nickles

1.4k(I hadn't "replied" to your post, so you may not have seen this)

Hi Antony, I've given it my best shot and got nowhere really. I respect your wish to have a particular kind of discussion, so I'm going to express my views about Wittgenstein in a new thread. — Daemon

Well, I'm sorry to hear that you don't feel you can contribute, and for my flippancy. I'm not sure the "particular kind of discussion" I'm suggesting should preclude much, but, if you want to talk about something entirely different, than, yes, another thread would be appropriate (I hope you will tag me with it, or however that works). Of course, if you simply disagree, I'm willing to hear why; or if it's just confusion, I'll take any questions you have. Thank you in any event for reading it, twice. -

Antony Nickles

1.4k

Antony Nickles

1.4k

Maybe try not to think of it so much as an argument with a thesis as a reading to put you in a certain perspective to a certain history of philosophy (particularly positivism). Maybe start with trying to see the purpose of the lion-quote on this page: as a fact to contrast against the rest of the paragraphs (within all the possibilities it could be taken or used--within its 'grammar' Witt would say, or the 'sense' of it used here), and then work backwards, as the ripple-effects begin with that sentence and go deeper, contrasted to other mis-readings.I've read it all twice and thought about it. You may be right that the sentence needs to be read in context, but I don't understand the context. — Daemon -

Luke

2.7k" 'I cannot know what is going on in him' is above all a picture. It is the convincing expression of a conviction. It does not give the reasons for the conviction. They are not readily accessible."

Luke

2.7k" 'I cannot know what is going on in him' is above all a picture. It is the convincing expression of a conviction. It does not give the reasons for the conviction. They are not readily accessible."

The "cannot" here I strongly impress upon you to find a way to see is in contrast to the "could not" in the lion sentence. ("If a lion could talk, we could not understand him.")

As in (placing the phrasing in parallel structure): 'Now HERE [with the lion] we COULD NOT understand him'--as in, it is impossible, a fact (see ** below)--but with the person saying they 'CANNOT know' another person, this is a conviction--a decision or firm belief. [The ’quotes’ are only a re-phrasing of Witt.]

And so we CAN (as opposed to the lion) know what is “going on in him” (though see *** below), and saying we cannot is a conviction, a belief (in this example, in a particular picture; roughly, that meaning is tied to an idea). Apart from just the conviction in the picture though, Witt is making a point that we are responsible in how we treat the other. It is an ethical argument, not (merely) an epistemological one. The conviction is a person's choice not to ACCEPT what is going on in the other, as opposed to how it would be with the lion, where we simply can NOT understand there (it is a fact, not a choice). — Antony Nickles

Are you saying that it is a person's (ethical?) choice not to understand a lion? Or are you saying that it is impossible to understand a lion (as "a fact, not a choice")? It seems to be the latter. Couldn't we make a choice to try and understand a lion?

Also, do you think Wittgenstein uses the terms "know" and "understand" synonymously? -

Antony Nickles

1.4k

Antony Nickles

1.4k

First, it is not made as a claim nor said as a statement to be considered (which are obviously within its possibilities of sense). This is a lesson in how words (sentences) can be used in specific ways. The use of this statement is as a fact, to be contrasted with the conviction, or the strangeness of traditions. Let me put it another way: if a lion talked, we would no longer understand it to be a lion. We can of course understand lions, say, study them. But, yes, this is simply meant to be an uncontested fact, used for comparison. The choice (conviction) regards the other (person). -

Luke

2.7kThe use of this statement is as a fact, to be contrasted with the conviction, or the strangeness of traditions... But, yes, this is simply meant to be an uncontested fact, used for comparison. — Antony Nickles

Luke

2.7kThe use of this statement is as a fact, to be contrasted with the conviction, or the strangeness of traditions... But, yes, this is simply meant to be an uncontested fact, used for comparison. — Antony Nickles

I think you need to provide more support for this reading. Why couldn't it be another example of "the convincing expression of a conviction"? Or something else? Wittgenstein isn't the easiest philosopher to get a handle on and "if a lion could talk" is one of his more enigmatic statements. Your reading may be correct but I don't yet follow why it is, or what you're trying to say exactly. I'm also curious about the other parts of your discussion title re: qualia and forms of life which you said little about in your OP. -

Antony Nickles

1.4k

Antony Nickles

1.4k

I think you need to provide more support for this reading. Why couldn't it be another example of "the convincing expression of a conviction"? Or something else? — Luke

There are other ways this sentence could be used, yes, but that doesn't mean I have to refute all of them (that it is any of those). The reading is internally coherent and based on the textual evidence. I realize it might be hard to see/accept, but I have pointed out the comparative examples, his actual statements about how he uses facts, his use of them elsewhere, the impact to the rest of the text, and the parallel structure to the previous sentence (if you switch the clause) that highlights the comparison:

"I cannot know what is going on in him"

"We could not understand a lion if it talked."

The first is a refusal, the second is an impossibility.

Is there (do you have) another way (attempt) to account for all of this evidence? The statement is not enigmatic if you accept and focus on its use. It is a "very general fact[ ] of nature (Such facts as mostly do not strike us because of their generality)” #143. Could he have used a simpler fact? Yes. Could it maybe not have been from an imagined world? Maybe. Is he goading the positivist? Maybe he feels this stark contrast, however fantastical, would be shocking enough for people to reassess the need to have a fixed referent.

Wittgenstein isn't the easiest philosopher to get a handle on and "if a lion could talk" is one of his more enigmatic statements. — Luke

I would say that the point of putting this fact here is enigmatic, but that's my whole discussion (start with letting go of the assumption that this is used as the kind of "statement" philosophy historically defines--say, a claim based on a theory). I will also say that it is illustrative of Witt's method of looking at the use of language, which is indicative of Ordinary Language Philosophy--is this a threat? an apology? a refusal? a plea?

I'm also curious about the other parts of your discussion title re: qualia and forms of life which you said little about in your OP. — Luke

I do mention those in the post, but they come from a viewpoint based on a desire for certainty basically. If you want to be able to fix words or speech to something inside the brain (ideas, thoughts, mental occurrences; what has been termed 'qualia') then hanging onto that makes it hard to shift to seeing the motivation for that, which Witt is pointing out. So some, out of the same desire, have latched onto his term of Forms of Life, as a communal agreement, or a type of rule, that ensures the meaning of words. I would need maybe a little more to understand where you're getting hung up, or what you are interested in discussing, but I appreciate the consideration. -

Mww

5.4klabeling Witt’s sentences as “Thesis” is not exactly accurate. — Antony Nickles

Mww

5.4klabeling Witt’s sentences as “Thesis” is not exactly accurate. — Antony Nickles

I meant it as indicating the opening statement as affirmation, in accordance with continental dialectical reasoning, re: German idealists in general. The antithesis, then, follows as subjecting the opening to negation, or just some sort of modification. I didn’t label W’s statements themselves in any way at all; I just copied them verbatim. Still, I could have used point/counterpoint, so......

—————

The “unperceived physical proceedings” are the writing and the jig-saw puzzles, etc.—which are hidden in the sense of, away from view. — Antony Nickles

Hidden from the guy, yes. I just went off on a rant over the gross dissimilarities between empirical invisibility and rational invisibility, and how silly it is to juxtaposition one against the other.

Anyway.....good talk, and, carry on. -

Antony Nickles

1.4k

Antony Nickles

1.4k

Also, do you think Wittgenstein uses the terms "know" and "understand" synonymously? — Luke

After looking around in the book, I would say, sometimes its close, but not here. As with most words, the 'grammar' of the word allows for many senses (and for new ones). Knows, as: has knowledge; as: acknowledges; as: familiar with; as: know how to continue, etc. Understands, as: understands how to (do a procedure); as: commiserates with (a person); as: can follow (what someone is saying, their point), etc.

They are not fluid as much as multifaceted. At one point Witt says: "The grammar of the words "knows" is evidently closely related to that of "can", "is able to". But also closely related to that of "understands". ('Mastery of a technique.) #150. And also at one point talks about how understanding a sentence is being able to paraphrase it, but understanding a poem can only be said one way. After his interlocutor says: "Then has 'understanding' two different meanings here?--I [Witt now] would rather say that these kind of use of 'understanding'' make up its meaning, make up my concept of understanding."#531-532. Concept not being an idea but a term to encompass all the different senses, uses, possibilities, etc. of a word (its "grammar" he calls it).

But on page 223, knowledge (saying, I know) is most often used by him to mean the certainty people want for their words or other people--the positivist version of knowledge--either as a fixed internal or external thing ('thought' or 'tradition'). Understanding here is I would say more tied to: can follow what they are saying (the point; why; where they are coming from, etc.) We might not be able to say what a clarinet sounds like (#78), what a game is (#75), but we can demonstrate that we understand those things (are familiar with, can be said to; e.g., give examples, compare to a flute, etc.) He is not using a definition of understanding nor does understanding consist of one thing. -

Antony Nickles

1.4k

Antony Nickles

1.4k

I meant it as indicating the opening statement as affirmation, in accordance with continental dialectical reasoning, re: German idealists in general. The antithesis, then, follows as subjecting the opening to negation, or just some sort of modification.... Still, I could have used point/counterpoint, so...... — Mmw

Not to belabor this, but I would suggest Witt ( and OLP) does not play by those rules: affirmation, negation, points to counter, etc.--again, these (mostly) are not meant as statements, say: to be taken as true/false distinctions, or as claims. He's trying to get the reader to see from a different viewpoint. I only worry about trying to force this text to meet a pre-determined criteria (idea of reason), as one of the main points of Ordinary Language Philosophy would be there are different kinds of reasoning ("grammar") for each concept, each word in a sense: "knowing" "understanding" "acknowledging" "reason" and even for just a kind of situation, and even without being closed, fixed, or certain. And I wouldn't call Witt a German Idealist, but even Hegel's method was to unpack simple juxtapositions, and Kant had roughly the same idea as grammar with his categories (though singular criteria and limited application).

I just went off on a rant over the gross dissimilarities between emperical invisibility and rational invisibility, and how silly it is to juxtaposition one against the other. — Mmw

Again, I hate to be a stickler, but the juxtaposition is the whole point. The comparison with "emperical invisibility" (out of sight) starts down the road to figure out why philosophers might make up the idea of "rational invisibility" (as a hidden 'thing', not just unexpressed) and all of its offspring. -

Mww

5.4kHe's trying to get the reader to see from a different viewpoint. — Antony Nickles

Mww

5.4kHe's trying to get the reader to see from a different viewpoint. — Antony Nickles

Understood. I suppose that might work for one who hasn’t an entrenched viewpoint already. It may also work, even for him, if OLP made enough sense to displace it. Personally, I’m happy with what I got.....I better be, considering the time and effort I’ve invested in it.

No, I most certainly wouldn’t label W as a German idealist either; yes, Hegel unpacks juxtapositions....in his own profoundly roundabout way...., and I’d be interested in what you have to say about Kantian “grammar” with his categories. I’d be pleased to see how you correlate reasoning to grammar, from your “...one of the main points of Ordinary Language Philosophy would be there are different kinds of reasoning ("grammar")....”

I don’t wish to detract from your thread, so if your attention is warranted elsewhere, I can wait. -

Antony Nickles

1.4kI suppose that [getting the reader to see from a different viewpoint] might work for one who hasn’t an entrenched viewpoint already. It may also work, even for him, if OLP made enough sense to displace it. — Mww

Antony Nickles

1.4kI suppose that [getting the reader to see from a different viewpoint] might work for one who hasn’t an entrenched viewpoint already. It may also work, even for him, if OLP made enough sense to displace it. — Mww

Ouch. ; ) It is tough because OLP is more of a method and viewpoint than a theory; it doesn't have any force or particular logic to itself other than: "Hey, do you see this too?"". The place where I thought it made the most sense (other than J.L Austin's response to A.J. Ayer, though he doesn't bother to explain himself) was in Stanley Cavell's essays in Must We Mean What We Say, particularly the title essay--basically about intention--and "Knowing and "Acknowledging" which steps through the problem of other minds (like Witt here) but methodically and more straightforward.

I’d be pleased to see how you correlate reasoning to grammar, from your “...one of the main points of Ordinary Language Philosophy would be there are different kinds of reasoning ("grammar")....” — Mww

These may be another post(s), but, well briefly (Cavell addresses this in that title essay too), the OLP (Witt) idea of grammar is that each concept, say, knowing, or, an apology, has its own (or multiple) say, ways it can make sense, how it works (or fails): e.g., understanding--when can you say someone else understands something? how do you explain it? what is proof for understanding, say, math, a poem, a person? etc., each concept having its own (subject to change and adaptation as we change our judgments, standards, lives, etc: what is justice, these days?).

I’d be interested in what you have to say about Kantian “grammar” with his categories. — Mww

My Kant is questionable, but "grammar" would classify an action being a certain action--being identified as such. You can try to make an apology, but if it is said sarcastically it may not be understood/accepted as an apology (its a further rebuke, etc.); there are reasons essential to it being an apology; criteria it must meet. We could look at each concept as a category. To be in its category, a concept has its limits (when does a game break down into only playing?) This is a far cry from Kant's desire for his categories, but the structure of grammar is analogous--the sense of inclusion and exclusion, the rationality of criteria--though not the "imperative" of his logic/reason. There is not the same force (should) and inclusion is not determined deontologically (beforehand, for certain), but only usually after an act. "Did you mean to apologize? that just sounded like complaining. There wasn't any acceptance of wrong; no request for forgiveness!" -

Luke

2.7k"I cannot know what is going on in him"

Luke

2.7k"I cannot know what is going on in him"

"We could not understand a lion if it talked."

The first is a refusal, the second is an impossibility. — Antony Nickles

I'm not sure what you mean by an impossibility. Is it impossible that lions can talk? Yes, but Wittgenstein is getting us to imagine that a lion could talk, and given that case we could still not understand it. Is it impossible that we could not understand a lion if it talked? It's a conditional statement and hardly a self-evident fact. Why do you consider it such a straightforward fact that it would be impossible to understand a lion if it talked? Would it speak English or Lion?

Is there (do you have) another way (attempt) to account for all of this evidence? — Antony Nickles

I'm reluctant to get into it because I find it so enigmatic, but I might side with the quote from your OP: "because our context of 'understanding' is so radically different than that of a different species".

I will also say that it is illustrative of Witt's method of looking at the use of language — Antony Nickles

I agree that W is attempting to "turn our whole inquiry around" (PI108).

If you want to be able to fix words or speech to something inside the brain (ideas, thoughts, mental occurrences; what has been termed 'qualia') then hanging onto that makes it hard to shift to seeing the motivation for that, which Witt is pointing out. — Antony Nickles

Where does he talk about "fixing words or speech to something inside the brain"? I don't find the relationship between mind and body to be an immediately apparent goal of his investigations.

So some, out of the same desire, have latched onto his term of Forms of Life, as a communal agreement, or a type of rule, that ensures the meaning of words. — Antony Nickles

It sounds as though you take this to be a misunderstanding of Forms of Life. If so, what do you understand "Forms of Life" to mean or to be about?

Also, do you think Wittgenstein uses the terms "know" and "understand" synonymously?

— Luke

After looking around in the book, I would say, sometimes its close, but not here. As with most words, the 'grammar' of the word allows for many senses (and for new ones). Knows, as: has knowledge; as: acknowledges; as: familiar with; as: know how to continue, etc. Understands, as: understands how to (do a procedure); as: commiserates with (a person); as: can follow (what someone is saying, their point), etc. — Antony Nickles

If these terms are not synonymous, then doesn't this create a problem for your reading of:

"I cannot know what is going on in him"; and

"We could not understand a lion if it talked"?

Doesn't it loosen the connection you are wanting to draw between these? -

Antony Nickles

1.4k"I cannot know what is going on in him"

Antony Nickles

1.4k"I cannot know what is going on in him"

"We could not understand a lion if it talked."

The first is a refusal, the second is an impossibility.

— Antony Nickles

I'm not sure what you mean by an impossibility. Is it impossible that lions can talk? — Luke

What I should have said is Witt is using the statement in its sense of impossibility; as I did say, using the sentence as a given fact (it could be other things--in other texts, in other uses). The use (its fact-ness?) is more important than it being an isolated statement (an opinion or claim to be answered by an opinion or refuted). The problem is, isolated/taken as just the words, you are not wrong in everything you are saying. This is why Witt falls back on "use"--how it is meant (in what sense).

Wittgenstein is getting us to imagine that a lion could talk.... It's a conditional statement and hardly a self-evident fact. — Luke

My argument is that this is not being used (I'm not sure it helps to underline it anymore) as a conditional statement (though it can be seen that way--it is one of the possibilities of its grammar--but you would have to ignore the context) In this case (in this text, in relation to everything around it), he is not asking us to imagine a talking lion--it is being said as an accepted fact ("if", "then", no buts). If he is asking us to imagine something, what sense do the sentences around it make? -

Luke

2.7kWhat I should have said is Witt is using its impossibility; as I did say, using it as a fact — Antony Nickles

Luke

2.7kWhat I should have said is Witt is using its impossibility; as I did say, using it as a fact — Antony Nickles

On your reading, he's using the impossibility as a fact. Okay.

My argument is that this is not being used as a conditional statement — Antony Nickles

How can it be otherwise? Lions can't talk.

If he is asking us to imagine something, what sense do the sentences around it make? — Antony Nickles

I don't think it's clear, but I'm not sold on your reading. At least, not yet. -

Antony Nickles

1.4kIf you want to be able to fix words or speech to something inside the brain (ideas, thoughts, mental occurrences; what has been termed 'qualia') then hanging onto that makes it hard to shift to seeing the motivation for that, which Witt is pointing out.

Antony Nickles

1.4kIf you want to be able to fix words or speech to something inside the brain (ideas, thoughts, mental occurrences; what has been termed 'qualia') then hanging onto that makes it hard to shift to seeing the motivation for that, which Witt is pointing out.

— Antony Nickles

Where does he talk about "fixing words or speech to something inside the brain"? I don't find the relationship between mind and body to be an immediately apparent goal of his investigations. — Luke

Well this isn't the stretch where that is looked into in detail, that's on me. But the interlocutor's desire to have, his worry about, something "hidden", is evident here. If something isn't hidden in the other, it could be there is nothing I can hide, or nothing special about me--which leads to the thought: I can't know his pain, but he MUST be able to know it (and I, me)(see @Mmw here)--which is the desire not to have to understand the other, be responsible (and for what I say). "Thought is connected to words, and I know those words, so I know him"--without me having anything to do with it. I'm just working from the very end of that journey, where he is exploring the ethical situation we are left with when that desire is abandoned. -

Antony Nickles

1.4kSo some, out of the same desire, have latched onto his term of Forms of Life, as a communal agreement, or a type of rule, that ensures the meaning of words.

Antony Nickles

1.4kSo some, out of the same desire, have latched onto his term of Forms of Life, as a communal agreement, or a type of rule, that ensures the meaning of words.

— Antony Nickles

It sounds as though you take this to be a misunderstanding of Forms of Life. If so, what do you understand "Forms of Life" to mean or to be about? — Luke

This is also outside of this text, but Witt points out the variety of our forms of life to get us to see the variety of how the world makes sense (has reason)--not just word=object, or true/false statements. I only point out the analogous use some people make of it as with hidden internal somethings--the desire to secure language from skepticism (ground it from confusion, misunderstanding), to remove the human from the activity of communicating. -

Antony Nickles

1.4kIf these terms [knowledge and understanding] are not synonymous, then doesn't this create a problem for your reading of:

Antony Nickles

1.4kIf these terms [knowledge and understanding] are not synonymous, then doesn't this create a problem for your reading of:

"I cannot know what is going on in him"; and

"We could not understand a lion if it talked"?

Doesn't it loosen the connection you are wanting to draw between these? — Luke

Well, you got me there, though I believe the point still stands. He is going back and forth between the two, and the difference between wanting certain knowledge, and being able to understand the other, intersect here in Witt's use in their mutual sense of: trying to figure out what to do with the other, how to address them. Object of knowledge? or understanding how to go on with them? (both maybe?) -

Antony Nickles

1.4k

Antony Nickles

1.4k

What I should have said is Witt is using its impossibility; as I did say, using it as a fact

— Antony Nickles

On your reading, he's using the impossibility as a fact. Okay. — Luke

I got my "it"s confused; not using the impossibility as a fact, using the statement as a fact.

My argument is that this is not being used as a conditional statement

— Antony Nickles

How can it be otherwise? Lions can't talk. — Luke

Yes, it is a statement, among other things. It is not being used for its possibility to state something--to claim itself as a fact; to stand to be refuted; it is being used in its uncontested fact-ness, for comparison to a choice. As you say, Lions can't talk. If someone says they cannot know another, that is a belief. "A dog cannot be a hypocrite, but neither can he be sincere" p. 229 This fact is being used in comparison to a baby who will be able to pretend, but not without learning many things beforehand.

And to provide the full quote from p. 56 (right after#143): What we have to mention in order to explain the significance, I mean the importance, of a concept, are often extremely general facts of nature: as are hardly ever mentioned because of their great generailty." -

Olivier5

6.2kIf a lion could talk, we could not understand him." Ludwig Wittgenstein, — Antony Nickles

Olivier5

6.2kIf a lion could talk, we could not understand him." Ludwig Wittgenstein, — Antony Nickles

« If Wittgenstein could roar, nobody could understand him. »

— A lion -

Deleted User

0I am having a hard time figuring out if the OP does deal with the issue your cartoon humorously took up. But since the cartoon does, I'll drop in. Lions already have a very simple speech and not only can lay people understand some of these 'words' (when watching them interact with each other for example) there are people well versed in lion language. And that's because our lives overlap with lion lives. Perhaps if a lichen could talk I'd never understand, but jeez, lions are social mammals, of course we'd understand many things they said. Back off would probably one of the first things we'd learn and natural selection would weed out those social with lions who couldn't figure out what the lion meant.

Deleted User

0I am having a hard time figuring out if the OP does deal with the issue your cartoon humorously took up. But since the cartoon does, I'll drop in. Lions already have a very simple speech and not only can lay people understand some of these 'words' (when watching them interact with each other for example) there are people well versed in lion language. And that's because our lives overlap with lion lives. Perhaps if a lichen could talk I'd never understand, but jeez, lions are social mammals, of course we'd understand many things they said. Back off would probably one of the first things we'd learn and natural selection would weed out those social with lions who couldn't figure out what the lion meant.

If the Kardashian's could talk, I wouldn't understand them. Because they do and I don't. -

Banno

30.6kCheers.

Banno

30.6kCheers.

@StreetlightX made a thread on this topic a few years back.

Lions and Grammar

I think Wittgenstein was making a joke. Either that, or he was wrong.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- An argument for the non-existence of God based on Wittgenstein's theory about Ethics (+ criticism)

- Dissolving normative ethics into meta-ethics and ethical sciences

- Bedrock Rules: The Mathematical and The Ordinary (Cavell-Kripke on Wittgenstein)

- "The Ethics of Eating Meat" -- why is that a question of ethics? It's a question of kindness.

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum