-

Andrew M

1.6kCould we say that the meaning of "the world as it is" depends on the context? The world has perceptible and imperceptible aspects, and on a day to day basis we usually want to talk about the world we perceive. — Daemon

Andrew M

1.6kCould we say that the meaning of "the world as it is" depends on the context? The world has perceptible and imperceptible aspects, and on a day to day basis we usually want to talk about the world we perceive. — Daemon

Yes, that seems fine.

I'd add that knowledge (whether everyday or scientific) builds on what we ordinarily perceive.

One aspect where philosophical claims and distinctions can go wrong is when they deny that premise - in effect, sawing off the branch that they rest on. -

BC

14.2kI conclude that nobody can see the world as it is. — Daemon

BC

14.2kI conclude that nobody can see the world as it is. — Daemon

The-world-as-it-is can only be a human concept, in the end based on experience. The-world-as-it-is might not be accessible if we had no reliable, repeatable, valid sensory experience of the world. Because we have reliable, repeatable, valid sensory experience of the world, we can say we see the world as it is. Were sensory experience highly variable (such that some people perceived water as dry, fire as cool, thunder as a sucking sensation, and so on), we couldn't say the world is as we see it. -

Olivier5

6.2kWere sensory experience highly variable (such that some people perceived water as dry, fire as cool, thunder as a sucking sensation, and so on), we couldn't say the world is as we see it. — Bitter Crank

Olivier5

6.2kWere sensory experience highly variable (such that some people perceived water as dry, fire as cool, thunder as a sucking sensation, and so on), we couldn't say the world is as we see it. — Bitter Crank

When two people seeing the world as it is disagree about what it is, are they seeing two different worlds? -

BC

14.2kWe reach a consensus. I have poor vision; what my senses tell me about the world as it is will not be the same as someone with excellent vision. We compare notes and we find that there is significant overlap. I rarely see brightly colored birds; they all appear pretty much dark gray or black to me, unless they were eating at a feeder near a window. I've seen pictures, and people very enthusiastically report seeing such and such bird with brightly colored feathers. I've seen many pigeons, crows, starlings, chickens, wild ducks, and geese--and what I see of them fits with what people say about bluejays, cardinals, bluebirds, redwing blackbirds, goldfinches, and so on. We reach a consensus.

BC

14.2kWe reach a consensus. I have poor vision; what my senses tell me about the world as it is will not be the same as someone with excellent vision. We compare notes and we find that there is significant overlap. I rarely see brightly colored birds; they all appear pretty much dark gray or black to me, unless they were eating at a feeder near a window. I've seen pictures, and people very enthusiastically report seeing such and such bird with brightly colored feathers. I've seen many pigeons, crows, starlings, chickens, wild ducks, and geese--and what I see of them fits with what people say about bluejays, cardinals, bluebirds, redwing blackbirds, goldfinches, and so on. We reach a consensus.

We have to learn to see the world as it is. Rock layers don't tell a story until one learns something about rocks--sediment, metamorphosis, uplift, folding, erosion, and so on. Same with all the different parts of the world as it is. -

Mww

5.4kBecause we have reliable, repeatable, valid sensory experience of the world, we can say we see the world as it is. — Bitter Crank

Mww

5.4kBecause we have reliable, repeatable, valid sensory experience of the world, we can say we see the world as it is. — Bitter Crank

I’ve always been under the impression that’s exactly the opposite of what “as it is” implies, which technically expands to “as it is in itself”. Because of the very limitations of our experiential methodology, and the cognitive system inherent in humans in general by which such experience is given, we can only say we see the world as it appears to us, as it seems to be as far as we are equipped to say. Which is the off-hand source of the metaphysically-induced invention of qualia.

Does the world appear to us as it is in itself, is the question with no positive proof, but pure speculative epistemology says it is not, nor can it be. Just for fun, throw in energy conversion losses, and even the scientists should agree.

For whatever that’s worth....... -

Marchesk

4.6kI’ve always been under the impression that’s exactly the opposite of what “as it is” implies, which technically expands to “as it is in itself”. — Mww

Marchesk

4.6kI’ve always been under the impression that’s exactly the opposite of what “as it is” implies, which technically expands to “as it is in itself”. — Mww

It is the opposite. That we have to work hard, applying a rigorous methodology of experimentation with a heavy reliance on math, resulting in many counter intuitive or surprising results means the world as it i differs considerably from the world as it is.

The whole realty/appearance distinction, which wouldn't be a thing if the world appeared to us as it is. -

Wayfarer

26.1kIt ought to be acknowledged that a large part of the philosophy of The Enlightenment comprised the rejection of metaphysics (as per David Hume's entreaty at the end of the Enquiry, 'commit it to the flames'.) 'Let's start afresh, see the world as it really is, stripped of all this philosophico/religious mumbo jumbo.'

Wayfarer

26.1kIt ought to be acknowledged that a large part of the philosophy of The Enlightenment comprised the rejection of metaphysics (as per David Hume's entreaty at the end of the Enquiry, 'commit it to the flames'.) 'Let's start afresh, see the world as it really is, stripped of all this philosophico/religious mumbo jumbo.'

What that doesn't get, is that within the scholastic tradition, ossified and dogmatic though it might have become, was a critical philosophy. It contained the gist of the dialectical tradition of Greek philosophy which had been developed over centuries, and refined through subsequent debate and analysis, preserved in Aristotelian and Platonic philosophy and its commentaries.

Throwing it out, and starting again with naturalism, results in the loss of the framework to even discuss the question of 'reality and appearance'. Kant realised this, and preserved some of those elements, even while transforming them in light of science. But Kant is very difficult, and besides, his work became identified with subsequent German idealism, which is highly complex, not to say unbearably verbose. The upshot is that philosophy as such more or less died out in Western culture, although the questions it originally sought to tackle always re-assert themselves in new guises. -

Olivier5

6.2kThe point is that you cannot account for something as simple as a disagreement if we all see and know the world ‘as it is’. For there is only one world, and many different views about it...

Olivier5

6.2kThe point is that you cannot account for something as simple as a disagreement if we all see and know the world ‘as it is’. For there is only one world, and many different views about it...

Likewise, the assumption renders one unable to account for individual bias. -

Janus

18kIt's a misunderstanding to think that metaphysics has been eliminated from philosophy. The discipline has merely been transformed from being an exercise of the imagination more akin to poetry than to science, to an attempt to understand the nature of reality in light of the new and ever-evolving ways of understanding the world that science has produced.

Janus

18kIt's a misunderstanding to think that metaphysics has been eliminated from philosophy. The discipline has merely been transformed from being an exercise of the imagination more akin to poetry than to science, to an attempt to understand the nature of reality in light of the new and ever-evolving ways of understanding the world that science has produced.

If you wish to educate yourself about the transformation of metaphysics from the ancient to the modern, this would be a good start:

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/metaphysics/ -

Wayfarer

26.1kIt's a misunderstanding to think that metaphysics has been eliminated from philosophy. — Janus

Wayfarer

26.1kIt's a misunderstanding to think that metaphysics has been eliminated from philosophy. — Janus

In practice, empiricism, and positivism, usually turn out to be precisely the 'elimation of metaphysics from philosophy'. In positivism it is overt. As I've observed before, and despite your denials, your criticism of metaphysics as 'akin to poetry' is indeed 'akin to positivism'. ;-)

Of course there are still people who study metaphysics, but again, empiricism and a lot of English-speaking analytical philosophy is hostile to metaphysics.

And do notice that the SEP entry you've pointed to - which I'm familiar with, surprising as that might be - concludes with a section under the heading 'is metaphysics possible?'

I'm not advocating for any kind of return to classical metaphysics. But you would have to agree there's very little discussion of it on this forum, and precious little evidence that it's understood, going on many of the discussions here. And it was was precisely the subject of this OP that metaphysics originally set out to discern. -

BC

14.2kI have entertained the notion that the world as we experience may be, in truth, much different than we think it is. Perhaps we would be shocked to see it with sensory abilities we do not have. Perhaps the true perception of the world would show that it is phantasmagorical. [Something phantasmagoric features wild and shifting images, colorful patterns that are continually moving and changing. The Greek word phantasma, meaning "image," is the ancestor of phantasmagoric, a word you can use to describe anything so weird it doesn't seem real.]

BC

14.2kI have entertained the notion that the world as we experience may be, in truth, much different than we think it is. Perhaps we would be shocked to see it with sensory abilities we do not have. Perhaps the true perception of the world would show that it is phantasmagorical. [Something phantasmagoric features wild and shifting images, colorful patterns that are continually moving and changing. The Greek word phantasma, meaning "image," is the ancestor of phantasmagoric, a word you can use to describe anything so weird it doesn't seem real.]

The problem with that conclusion (for me, anyway) is that I still exist in the world I perceive and interact with. If the world is, in fact, quite unlike what we perceive, what difference can it make to me? If the solidity in the world I perceive is in truth fluid, well... it seems solid, and solid works.

Yeats' poem, The Second Coming, suggests what it would be like if the 'much different and true reality' should become perceptible:

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world -

Janus

18kDid you read the section on the 'New Metaphysics'? There are plenty of philosophers working in that area.

Janus

18kDid you read the section on the 'New Metaphysics'? There are plenty of philosophers working in that area.

My saying that ancient and medieval metaphysics was more akin to poetry than to science was not a criticism, but merely an observation. I think it's undeniable that traditional metaphysics was an unconstrained (except by logical consistency, of course) exploration of the theological and poetic imagination; and there's absolutely nothing wrong with that.

The point is that that practice does not deliver any theses that can be tested, or even that can be warranted as being ontological commitments elicited by, and consistent with, our best scientific understandings of the world. And apart from those scientific understandings there would seem to be no other universally intersubjective, normatively compelling understandings (none which would compel any particular metaphysical commitments at least).

I think the question as to whether metaphysics is possible is a reasonable one. On the one hand of course it is possible, but on the other hand no worldview, scientific or otherwise can be definitively demonstrated to be veracious. Judgements as to the plausibility of worldviews is contingent on what criteria one selects. Personally, I don't think that the deliverances of modern science can be safely ignored if one wants to find a plausible worldview. -

Janus

18kYeats' poem, The Second Coming, suggests what it would be like if the 'much different and true reality' should become perceptible:

Janus

18kYeats' poem, The Second Coming, suggests what it would be like if the 'much different and true reality' should become perceptible:

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world — Bitter Crank

Yes, it seems that our perceptual processes are largely eliminative; the significant aspects of the "buzzing, blooming confusion" are retained and the chaotic, meaningless "noise" is filtered out. That chaos could never be "a much different and true reality", as the notion of reality seems to entail coherency. Hallucinogens give us a glimpse of that of which we cannot sensibly speak. -

Olivier5

6.2kYeats' poem, The Second Coming, suggests what it would be like if the 'much different and true reality' should become perceptible: — Bitter Crank

Olivier5

6.2kYeats' poem, The Second Coming, suggests what it would be like if the 'much different and true reality' should become perceptible: — Bitter Crank

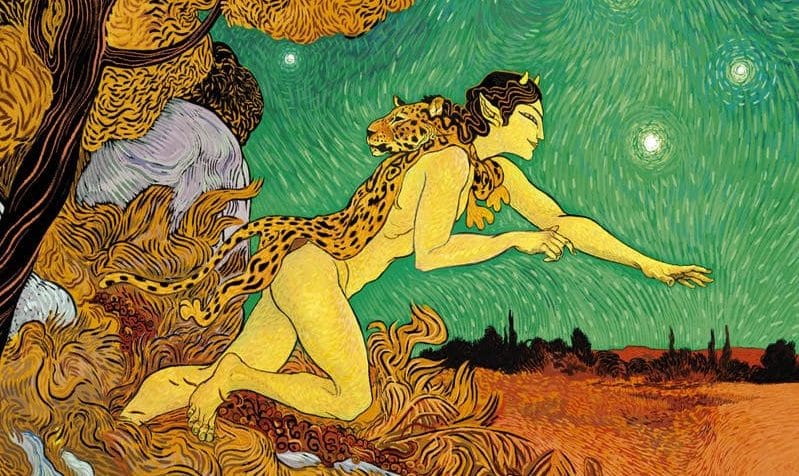

I prefer the version of Fabrizio Dori in Le Dieu Vagabond (The Wandering God), which tells the story of Eustis, a Greek god, a satire to be precise, from the retinue of Dionysos, wandering in the modern world as a bum. If you give him a bottle of wine, he will tell you your future. Like all gods, he sees the world as it really is, not the pale version that human eyes can see. Once, only once, Eustis lent his eyes to a mortal, a painter, who wanted very badly to see the world as it is. After he saw the world through the eyes of Eustis, the painter started to work furiously on canvas after canvas, to try and capture the vision he just had. But the beauty of this vision was so great that the artist started to despair of his ability to paint it, and committed suicide. His name was Vincent Van Gogh... Since then Eustis does not allow men to see the world through his eyes, even in exchange for a lot of wine. -

Wayfarer

26.1kDid you read the section on the 'New Metaphysics'? There are plenty of philosophers working in that area. — Janus

Wayfarer

26.1kDid you read the section on the 'New Metaphysics'? There are plenty of philosophers working in that area. — Janus

Yes, and indeed there are. It was a comment on this particular thread, and some of the gormless and jejune naive realism that's been on display here.

(Anyway, Happy Christmas. I'm going to log out for a couple of days, it's family time. :sparkle: ) -

BC

14.2kYes, and indeed there are. It was a comment on this particular thread, and some of the gormless and jejune naive realism that's been on display here. — Wayfarer

BC

14.2kYes, and indeed there are. It was a comment on this particular thread, and some of the gormless and jejune naive realism that's been on display here. — Wayfarer

Well, you're on your way to celebrate the holy day with family; Merry [or happy] Christmas.

But... "gormless" is a lovely word. I've only read it here.

adjective Chiefly British Informal.

lacking in vitality or intelligence; stupid, dull, or clumsy.

Mid 19th century, respelling of gaumless. -

Wayfarer

26.1k"gormless" is a lovely word. I've only read it here. — Bitter Crank

Wayfarer

26.1k"gormless" is a lovely word. I've only read it here. — Bitter Crank

Yes. There was this young chap who used to be runner for the Physics Department, back in the late 80's when I was managing the Uni computer store. He used to go back and forth picking up orders and the like. He was always running, always poorly shaven, always wore khaki shorts and had never smiled. When we saw him coming, we used to intone, in an Attenborough-ish voice - 'Studies in Gormlessness'.

And Merry Christmas to you, also BC. :sparkle: -

Olivier5

6.2kI'm not familiar with Eustis; but it's a good story (apropo). Thanks. — Bitter Crank

Olivier5

6.2kI'm not familiar with Eustis; but it's a good story (apropo). Thanks. — Bitter Crank

It’s one of many good stories in a stupendous graphic novel by Italian Fabrizio Dori, called Il Dio Vagabondo (the Vagrant God). I don’t think it has been translated in English yet. It should be, it’s a masterpiece.

Imagine a minor olympian divinity left alone in our modern, disenchanted world. Other gods of old, his companions, have disappeared when Christianity swept over the world. He lives by himself in a sunflower field, and he drinks a lot — aptly so, for ‘Eustis’ means ‘good grapes’ in Greek and Eustis’ ex-boss, Dionysos, is the god of wine.

But in fact Eustis has only been banished by the gods in the world of mortals. An old professor will help him find his way to where his divine buddies are hiding from the cold and rational beings that humans have become.

Graphically, Il Dio Vagabondo functions as an homage to Van Gogh. As explained, in the novel Van Gogh saw through the eyes of Eustis once, and tried to paint the world as seen by the gods. Unfortunately, humans cannot stand the full extent of the world’s beauty, and Van Gogh was maddened by it and committed suicide.

Dori’s previous novel was about Gauguin, so he is quite ambitious both graphically and narratively.

-

Olivier5

6.2kin the novel Van Gogh saw through the eyes of Eustis once, and tried to paint the world as seen by the gods — Olivier5

Olivier5

6.2kin the novel Van Gogh saw through the eyes of Eustis once, and tried to paint the world as seen by the gods — Olivier5

A possible interpretation is that the artist lends us his eyes to see the world in a new way, more meaningful, more beautiful than the way we usually see it, and in doing so, the artist helps us rediscover the primordial enchantement of being at the world. -

Deleted User

0The world has perceptible and imperceptible aspects, and on a day to day basis we usually want to talk about the world we perceive. — Daemon

Deleted User

0The world has perceptible and imperceptible aspects, and on a day to day basis we usually want to talk about the world we perceive. — Daemon

I conclude that nobody can see the world as it is. — Daemon

To me those statements just don't work well together. In the first you make a strong, unqualified statement, an ontological one, abot the world. In the second statement you make a blanket claim that we do not see the world as it is. If you believe the second claim, how can you make the first one? And since it seems like you arrive at your conclusion in the second statement via observations like the first one, why do you trust the second claim? -

Banno

30.6kCan we see the world as it is? What are you asking?

Banno

30.6kCan we see the world as it is? What are you asking?

If you mean "Are there things we cannot see with our own eyes" then yes, we know that here are because we can see them using various devices. Microbes and the moons of Jupiter, and as mentioned in the OP, ultraviolet light and magnetic fields.

If you mean "Are there things we have never seen" then yes. You've never seen your own heart, one hopes; but you know it is there from your understanding of anatomy and your continuing heartbeat.

If you mean "Are there things that could never be seen" then we move into modality. You will never see a round square, or a four sided triangle, but these are not things, just words put together without standing for anything. There's an interesting debate around whether we might find, say, unicorns on a distant planet; arguably, the answer is no, since unicorns are mythical creatures and hence horse-like beasts with horns growing out of their heads on other planets might look like unicorns, but would not be unicorns.

Then there is the metaphysical issue of whether a thing that could not in principle ever be seen counts as a thing; Catholics have blood that looks, smells and tastes like wine each Sunday. Is this blood that cannot be seen?

What are you asking? So far I've taken "see" to be roughly understood as "perceive". But it might mean something like "discern".

Can we discern the world as it is? Isn't that just asking if we can make true statements about how things are? And the answer to that is, yes, we can. It's true, for example, that you are reading this, now.

What I've writ so far is along the analytic tradition, breaking the question down into pieces and seeing if, by finding answers for each, we can answer the original question. Other approaches are more expansive, seeking to show the world in a different way, to expand our horizons. SO their question changes "Can we se the world as it is" to "Can we see the world as it is in itself" or "Can we see the world as it really is". The idea is that there is a world that stands outside our perceptions of it, and hence is outside of our capacity to discern. Further, this world, beyond our keen, is the actual thing. Since we cannot discern the goings on in this world as it is in itself, we cannot make statements about it, let alone true statements. On this view, there is precious little that we can say that is true.

I think that there is something fundamental here, and also something fundamentally erroneous. We cannot speak of the world as it is in itself. Then how can it have any significance? if it has no significance, why talk of it at all? One wants both to say that there are things of which we cannot speak; indeed, the most important things are there; and that since we cannot speak of them, anything we say about them is nonsense. The blood of Christ is such a profound nonsense. So are direct realism and transcendental idealism. They beat against the edge of language, as against the edge of the world.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Philosophical themes of The Lord of the Rings- our world reflected by Middle-Earth

- Reality: The world as experienced vs. the World in Itself

- From ADHD to World Peace (and other philosophical trains of thought)

- How do we know the objective world isn't just subjective?

- How do we know the subjective world isn't just objective?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum