-

Deleted User

0I like psychoanalysis too. Just discovering Lacan, didn't know he was such a big figure in the field.

Deleted User

0I like psychoanalysis too. Just discovering Lacan, didn't know he was such a big figure in the field.

I understand the link with shamanism. Travelling to the collective and individual subconscious seems to be the mutual therapy. It works.

Denmark is a beautiful country. Expensive though! But I suppose that doesn't matter so much when you live there. -

Fooloso4

6.2kNo actual sages in the sense of having divine knowledge.

Fooloso4

6.2kNo actual sages in the sense of having divine knowledge.

— Fooloso4

I don’t regard ‘divine knowledge’ as interchangeable with higher knowledge. Not all wisdom teachings are necessarily theistic. I suspect that it’s the reflexive association of ‘higher’ with ‘divine’ that is often at the basis of the rejection of the idea of ‘higher truth’. — Wayfarer

I was referring to Socrates and the distinction between human and divine wisdom. As I understand it, he points to the limits of human knowledge. I don't think Plato's teaching are theistic. It is, after all, the Good not the God.

In the Republic after Socrates presents theimage of the Forms Glaucon wants Socrates to tell them what the Forms themselves are. Socrates responds:

You will no longer be able to follow, dear Glaucon, although there won’t be any lack of eagerness on my part. But you would no longer seeing an image of what we are saying, but the truth itself, at least as it looks to me. Whether it really is so or not cannot be properly insisted on.(emphasis added) — 533a

Socrates presents an image of the truth not simply because that is all he can show Glaucon but because he cannot, to use another image, ascend the divided line from eikasía to noesis via dianoia, that is, from the imagination to insight via reason. Grasping hold of the truth remains out of our reach. While philosophers tend to focus on reason and dismiss the power of imagination, it is what art, religion, and philosophy have in common. It is why philosophers from Plato to Wittgenstein talk of philosophy as poetry, poiesis, the making of images.

What is "higher knowledge" and "higher truth"? Are they transcendent truths and knowledge? Exstatis? Are they truths and knowledge that you are privy to or just truths you believe others have attained? -

Wayfarer

26.1kWhat is "higher knowledge" and "higher truth"? — Fooloso4

Wayfarer

26.1kWhat is "higher knowledge" and "higher truth"? — Fooloso4

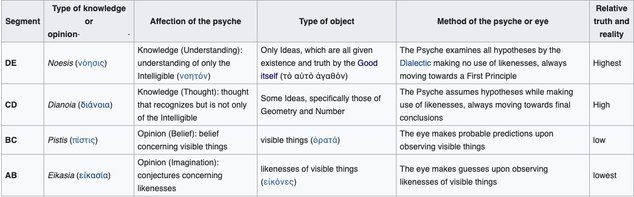

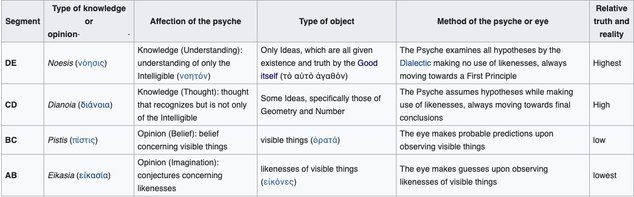

The wiki article on the Analogy of the Divided Line has a table:

So - isn't the whole task of the philosopher to ascend from from opinion through dianoia to noesis 'through dialectic'? Isn't that what the remainder of the passage is about? -

Deleteduserrc

2.8kComing in too late to read all the way through, but based on first-page: 'you shall know them by their fruits', a frame 180 referenced, is a good one. If there's such a thing as a 'true' sage, I imagine he'd show, not say (to tie it back to W) Last thing he'd be concerned with is establishing that there are true sages, and that he is one, or has studied under one.

Deleteduserrc

2.8kComing in too late to read all the way through, but based on first-page: 'you shall know them by their fruits', a frame 180 referenced, is a good one. If there's such a thing as a 'true' sage, I imagine he'd show, not say (to tie it back to W) Last thing he'd be concerned with is establishing that there are true sages, and that he is one, or has studied under one.

Of course, it's just a human fact that we desire recognition. You can't fault someone for desiring that, in moderation. But the thing of wanting to be recognized for recognizing the overcoming-of-recognition - that's a swampy space to be in. If, on the other hand, its possible to get outside that, you wouldn't, having gotten-out, need to be recognized for it. So either way, whether the esoteric is real or not, someone who seems to be asking to be recognized for being in alliance with the esoteric is probably not worth listening to, at least not on the subject of the esoteric (they might, if a lawyer, still have sound legal advice) (Even if esoteric knowledge is real, and they've tasted it, they're standing in their own way. I think the gospels are really good on this pragmatic issue.) -

j0e

443I like psychoanalysis too. Just discovering Lacan, didn't know he was such a big figure in the field. — TaySan

j0e

443I like psychoanalysis too. Just discovering Lacan, didn't know he was such a big figure in the field. — TaySan

He's controversial but taken up by fascinating philosophers like Zizek. Then Freud is taken up by Derrida and Rorty and others. So I think there's a continuum between philosophy and psychoanalysis (both of which might be called (self-criticizing) 'folk-psychology' at times.)

I understand the link with shamanism. Travelling to the collective and individual subconscious seems to be the mutual therapy. It works. — TaySan

Right. I was thinking that even if one questioned the scientific status that it's at least literature or myth that could help people orient themselves, work out their kinks (or work in their kinks.) Bloom read Freud as a modern myth maker.

Denmark is a beautiful country. Expensive though! But I suppose that doesn't matter so much when you live there. — TaySan

I believe you, and yeah I wouldn't just want to be a tourist. I couldn't afford it. -

j0e

443like to read these kinds of books, but I don't necessarily agree with all the ideas. — Jack Cummins

j0e

443like to read these kinds of books, but I don't necessarily agree with all the ideas. — Jack Cummins

Same here. I've actually ordered the paperback version of Lange's History of Materialism and just last night The Garden of Epicurus by Anatole France. I love the 'lost' perspectives. As you say, it's not about agreement but just exploring what other ages found acceptable and interesting. (& picking books that only tell us what we want to hear is of course a questionable strategy. ) -

Fooloso4

6.2kSo - isn't the whole task of the philosopher to ascend from from opinion through dianoia to noesis 'through dialectic'? Isn't that what the remainder of the passage is about? — Wayfarer

Fooloso4

6.2kSo - isn't the whole task of the philosopher to ascend from from opinion through dianoia to noesis 'through dialectic'? Isn't that what the remainder of the passage is about? — Wayfarer

Except that is not what happened in Socrates own case. The passage from the Republic 533a makes this clear. If what you mean by higher knowledge and truth is the leap from reason to intellection then I find it peculiar that Socrates never made that leap. The whole thing is an image of the truth, an image that "cannot be properly insisted on".

And so, if this is what you mean by "higher knowledge" and "higher truth", Socrates was not and never met a sage. -

j0e

443Grasping hold of the truth remains out of our reach. While philosophers tend to focus on reason and dismiss the power of imagination, it is what art, religion, and philosophy have in common. It is why philosophers from Plato to Wittgenstein talk of philosophy as poetry, poiesis, the making of images. — Fooloso4

j0e

443Grasping hold of the truth remains out of our reach. While philosophers tend to focus on reason and dismiss the power of imagination, it is what art, religion, and philosophy have in common. It is why philosophers from Plato to Wittgenstein talk of philosophy as poetry, poiesis, the making of images. — Fooloso4

:fire: :flower: :death:

(I'm enthusiastically agreeing.) -

j0e

443If there's such a thing as a 'true' sage, I imagine he'd show, not say — csalisbury

j0e

443If there's such a thing as a 'true' sage, I imagine he'd show, not say — csalisbury

Same here. -

Wayfarer

26.1kIf what you mean by higher knowledge and truth is the leap from reason to intellection then I find it peculiar that Socrates never made that leap. — Fooloso4

Wayfarer

26.1kIf what you mean by higher knowledge and truth is the leap from reason to intellection then I find it peculiar that Socrates never made that leap. — Fooloso4

But the implication is, Socrates has proceeded beyond 'image and symbol' - has indeed made that ascent - but that Glaucon cannot 'follow' him, i.e. is not equipped to understand his meaning:

And, if I could, I [Socrates] would show you, no longer an image and symbol of my meaning, but the very truth, as it appears to me—though whether rightly or not I may not properly affirm.

The footnote to this remark is that Socrates will not insist that he perceives rightly, as to do so would be dogmatic.

At any rate, the following passages discusses that one skilled in dialectic, i.e. the philosopher, is able to 'determine what each thing really is'.

“This, at any rate,” said I, “no one will maintain in dispute against us:

[533b] that there is any other way of inquiry that attempts systematically and in all cases to determine what each thing really is. But all the other arts have for their object the opinions and desires of men or are wholly concerned with generation and composition or with the service and tendance of the things that grow and are put together, while the remnant which we said did in some sort lay hold on reality—geometry and the studies that accompany it—

[533c]are, as we see, dreaming about being, but the clear waking vision of it is impossible for them as long as they leave the assumptions which they employ undisturbed and cannot give any account of them.

To deny this is to deny the possibility of the knowledge of the forms, and of the form of the Good, which is fundamental to the entire enterprise, or so it seems to me. -

j0e

443So either way, whether the esoteric is real or not, someone who seems to be asking to be recognized for being in alliance with the esoteric is probably not worth listening to, — csalisbury

j0e

443So either way, whether the esoteric is real or not, someone who seems to be asking to be recognized for being in alliance with the esoteric is probably not worth listening to, — csalisbury

I think there's a naturalized esotericism that's defensible (like an inner circle that gets some metaphor as a metaphor, or an inner circle that gets be bop.) But this stuff is all around us. So I think the issue is the intersection of esotericism and science, where esoteric statements try to rival science, where creation myths are taken as something like (quasi-)scientific hypotheses. As far as science goes, I pretty much boil it down to prediction and control. These are things that even non-experts can judge (at Quine's 'periphery.') No grand metaphysics need be attached as far as I can see. Do the tools work for everyone, whether one expects them to or not? (Esoteric statements might work very well within the inner circle by keeping up group morale, for instance, but this would involve expecting them to work, 'believing in' them.) -

Wayfarer

26.1kSocrates was not and never met a sage. — Fooloso4

Wayfarer

26.1kSocrates was not and never met a sage. — Fooloso4

A note from the IEP article on Pierre Hadot about the figure of the sage

A further, too-often neglected feature of the ancient conception on philosophy as a way of life, Hadot argues, was a set of discourses aiming to describe the figure of the Sage. The Sage was the living embodiment of wisdom, “the highest activity human beings can engage in . . . which is linked intimately to the excellence and virtue of the soul” (WAP 220). Across the schools, Socrates himself was agreed to have been perhaps the only living exemplification of such a figure (his avowed agnoia notwithstanding). Pyrrho and Epicurus were also accorded this elevated status in their respective schools, just as Sextius and Cato were deemed sages by Seneca, and Plotinus by Porphyry. Yet more important than documenting the lives of historical philosophers (although this was another ancient literary genre) was the idea of the Sage as “transcendent norm.” The aim, by picturing such figures, was to give “an idealized description of the specifics of the way of life” that was characteristic of the each of the different schools (WAP 224). The philosophical Sage, in all the ancient discourses, is characterized by a constant inner state of happiness or serenity. This has been achieved through minimizing his bodily and other needs, and thus attaining to the most complete independence (autarcheia) vis-à-vis external things. The Sage is for this reason capable of maintaining virtuous resolve and clarity of judgment in the face of the most overwhelming threats, from natural catastrophes to “the fury of citizens who ordain evil . . . [or] the face of a threatening tyrant” (Horace in WAP 223).

Again similar to the conception of the enlightened being in Buddhism. -

Tom Storm

10.8kIf there's such a thing as a 'true' sage, I imagine he'd show, not say

Tom Storm

10.8kIf there's such a thing as a 'true' sage, I imagine he'd show, not say

— csalisbury

Same here. — j0e

Sure. Of course there are those 'sages' who carefully orchestrate for others to testify on their behalf. Perhaps the origins of marketing.

The figure who I would choose as a kind of archetype of the Sage is Socrates. -

j0e

443The philosophical Sage, in all the ancient discourses, is characterized by a constant inner state of happiness or serenity. This has been achieved through minimizing his bodily and other needs, and thus attaining to the most complete independence (autarcheia) vis-à-vis external things. The Sage is for this reason capable of maintaining virtuous resolve and clarity of judgment in the face of the most overwhelming threats, from natural catastrophes to “the fury of citizens who ordain evil . . . [or] the face of a threatening tyrant”

j0e

443The philosophical Sage, in all the ancient discourses, is characterized by a constant inner state of happiness or serenity. This has been achieved through minimizing his bodily and other needs, and thus attaining to the most complete independence (autarcheia) vis-à-vis external things. The Sage is for this reason capable of maintaining virtuous resolve and clarity of judgment in the face of the most overwhelming threats, from natural catastrophes to “the fury of citizens who ordain evil . . . [or] the face of a threatening tyrant”

To me this seems like a point-at-infinity, an impossible ideal to strive toward. The image reminds me of a god or of God, a serene and benevolent transcendent intelligence. Christ and Socrates, both put to death, both symbolic for many of a kind of perfection. -

Deleteduserrc

2.8kI think there's a naturalized esotericism that's defensible (like an inner circle that gets some metaphor as a metaphor, or an inner circle that gets be bop.) But this stuff is all around us. So I think the issue is the intersection of esotericism and science, where esoteric statements try to rival science, where creation myths are taken as something like (quasi-)scientific hypotheses. As far as science goes, I pretty much boil it down to prediction and control. These are things that even non-experts can judge. No grand metaphysics need be attached as far as I can see. The epistemology might be stone - aged simple. Do the tools work for everyone, whether one expects them to or not? — j0e

Deleteduserrc

2.8kI think there's a naturalized esotericism that's defensible (like an inner circle that gets some metaphor as a metaphor, or an inner circle that gets be bop.) But this stuff is all around us. So I think the issue is the intersection of esotericism and science, where esoteric statements try to rival science, where creation myths are taken as something like (quasi-)scientific hypotheses. As far as science goes, I pretty much boil it down to prediction and control. These are things that even non-experts can judge. No grand metaphysics need be attached as far as I can see. The epistemology might be stone - aged simple. Do the tools work for everyone, whether one expects them to or not? — j0e

Yeah, when I think of naturalized esotericism, I tend to think of artistic movements. That sort of thing feels inevitable, and natural to me. Of course there will be the temptation for those, in a circle, to use their privileged space in the circle for esteem, sex etc - but, that's part of it, it's hard to find fault there.

(in some cases, it's less clear - a moralist's approach on inner circles, well thought-out: https://www.lewissociety.org/innerring/)

I think science is inherently predictive (repeatability being such a key part of the scientific method) but accidentally in service of control. 'Contingent' might be better than 'accidental.' But in any case, I think it's true science has tended to be in service of control. My personal feeling is that science is a sub-activity within the field-of-various-activities that is life, and any claims within that field are fine - anything that goes beyond that is also fine, but has extended beyond science, and is open to debate. -

Wayfarer

26.1kSo I think the issue is the intersection of esotericism and science, where esoteric statements try to rival science, where creation myths are taken as something like (quasi-)scientific hypotheses — j0e

Wayfarer

26.1kSo I think the issue is the intersection of esotericism and science, where esoteric statements try to rival science, where creation myths are taken as something like (quasi-)scientific hypotheses — j0e

Creationism and intellgent design are both instances of religious fundamentalism. They're as far from esoterica as you can get. The Copenhagen Interpretation of physics - now there's the esoteric in modern culture.

:up:The figure who I choose as a kind of archetype of the Sage is Socrates. — Tom Storm -

j0e

443Sure. Of course there are those 'sages' who carefully orchestrate for others to testify on their behalf. Perhaps the origins of marketing. — Tom Storm

j0e

443Sure. Of course there are those 'sages' who carefully orchestrate for others to testify on their behalf. Perhaps the origins of marketing. — Tom Storm

That's the clever way to do it! I googled Osho last night out of curiosity and saw the front page of the website. I find it nauseating, such blatant commercialization. The 'idealistic' or 'ascetic' or 'esoteric' part of me is gut-level against the hype and the open hand that fishes for dollars. Intuitively I expect it to be a gift, an overflow. Something modest that downplays the mere vessel of a universal insight. But I think we already have that here and there in mainstream philosophy. You just need a library card.

The figure who I choose as a kind of archetype of the Sage is Socrates. — Tom Storm

I relate to this, especially if Socrates is thought of as a critical, playful mind who faces death nobly. -

Tom Storm

10.8kOn Sages. How do we tell bogus from bonne fide?

Tom Storm

10.8kOn Sages. How do we tell bogus from bonne fide?

An old associate of mine worked for L Ron Hubbard back in the 1960's when he was at Saint Hill Manor. He called Hubbard a powerful and great sage.

What was the evidence for this, I asked?

He had exceptional power and control over his own body came the response.

I asked for an example.

One day LRH's hair would be grey and the next, through sheer will power, his hair had returned to its natural red color.

Hair dye? I suggested helpfully.

Impossible! came the response. -

j0e

443Creationism and intellgent design are both instances of religious fundamentalism. They're as far from esoterica as you can get. The Copenhagen Interpretation of physics - now there's the esoteric in modern culture. — Wayfarer

j0e

443Creationism and intellgent design are both instances of religious fundamentalism. They're as far from esoterica as you can get. The Copenhagen Interpretation of physics - now there's the esoteric in modern culture. — Wayfarer

I didn't have any particular theory in mind and I'm not trying to link you to creationism.

To what degree are esoteric statements functioning as quasi-scientific hypotheses, crossing into the turf of science?

What's the relationship between the esoteric, the metaphysical, and the scientific? -

j0e

443

j0e

443

I don't put all sage-types on the same level. I've checked some of them out. Anyone who gets famous just by talking has some kind of skill and insight. But I just cannot project some kind of 'trans-human' status on another human being. Obviously some people are generally wiser or or more virtuous or more skilled than others, but it's an uncertain continuum. We're all still fallible, vulnerable humans. -

j0e

443I think cience is inherently predictive (repeatability being such a key part of the scientific method) but accidentally in service of control. 'Contingent' might be better than 'accidental.' But in any case, I think it's true science has tended to be in service of control. — csalisbury

j0e

443I think cience is inherently predictive (repeatability being such a key part of the scientific method) but accidentally in service of control. 'Contingent' might be better than 'accidental.' But in any case, I think it's true science has tended to be in service of control. — csalisbury

Almost dinner time, but I'm intrigued by this. -

Wayfarer

26.1kTo what degree are esoteric statements functioning as quasi-scientific hypotheses, crossing into the turf of science? — j0e

Wayfarer

26.1kTo what degree are esoteric statements functioning as quasi-scientific hypotheses, crossing into the turf of science? — j0e

I'd say very rarely. The 'culture war' between religion and science, is mostly a conflict between scientific materialism, on the one side, and religious fundamentalism, on the other. Both parties to that conflict are lacking in philosophical discernment. Scientific materialism is caused by treating methodoligical naturalism, which is a perfectly sound principle, as a metaphysic, which it's not. Religious fundamentalism arises from treating religious allegory as a literal hypothesis, which it's not. That accounts for a large percentage of the alleged 'conflict'.

There's a story I often like to tell here, concerning Georges Lemaître, whom as you know came up with what is now known as big bang theory. In the wiki entry on him, it notes that:

By 1951, Pope Pius XII declared that Lemaître's theory provided a scientific validation for Catholicism. However, Lemaître resented the Pope's proclamation, stating that the theory was neutral and there was neither a connection nor a contradiction between his religion and his theory. Lemaître and Daniel O'Connell, the Pope's scientific advisor, persuaded the Pope not to mention Creationism publicly, and to stop making proclamations about cosmology. Lemaître was a devout Catholic, but opposed mixing science with religion, although he held that the two fields were not in conflict.

Devout Catholic, but not so devout as not to advise the Pope on what shouldn't be said! -

Janus

17.9kThe problem is that if there can be direct knowledge of reality, and that knowledge is deemed by the practitioners themselves to be esoteric, meaning available only those "ready" to receive it, then there can be no rational argument to justify it, since it is direct, meaning not mediated by anything, including reason. Also even if there were any rational aarguments they would fall on deaf ears unless the hearers were ready to hear them.

Janus

17.9kThe problem is that if there can be direct knowledge of reality, and that knowledge is deemed by the practitioners themselves to be esoteric, meaning available only those "ready" to receive it, then there can be no rational argument to justify it, since it is direct, meaning not mediated by anything, including reason. Also even if there were any rational aarguments they would fall on deaf ears unless the hearers were ready to hear them.

On the other hand if this esoteric knowledge is really only a kind of poetic feeling that can be cultivated by those who are so disposed, and is not really knowledge of the real at all, that is does not tell us anything about what is really the case as to the human condition and the truth about human life and death, then there also could be no rational justification of anything that is presumed to be known.

So, either way, it is not within the province of philosophy

which should be, in principle at least, open to anyone with the requisite capacity for valid rational thought. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI just cannot project some kind of 'trans-human' status on another human being. Obviously some people are generally wiser or or more virtuous or more skilled than others, but it's an uncertain continuum. We're all still fallible, vulnerable humans. — j0e

Wayfarer

26.1kI just cannot project some kind of 'trans-human' status on another human being. Obviously some people are generally wiser or or more virtuous or more skilled than others, but it's an uncertain continuum. We're all still fallible, vulnerable humans. — j0e

I think the 'ideal of the Sage' is one who has transcended fallible human nature. Philosophically speaking, the point of dualism is that the human is in some essential respect an instance of a universal intelligence which has taken birth in human form and then forgotten their real nature (hence anamnesis, 'un-forgetting). So the 'sage' awakens to his/her 'true nature' beyond the viscissitudes of physical existence. (That is even implicit in the NT - 'It is not I that live, but Christ liveth in me'Gal. 2:20) This is the substance of Alan Watts' book The Supreme Identity.

It is not within the province of philosophy — Janus

It's not within the provice of philosophy as now understood, that's for sure. -

Fooloso4

6.2kBut the implication is, Socrates has proceeded beyond 'image and symbol' - has indeed made that ascent - but that Glaucon cannot 'follow' him, i.e. is not equipped to understand his meaning — Wayfarer

Fooloso4

6.2kBut the implication is, Socrates has proceeded beyond 'image and symbol' - has indeed made that ascent - but that Glaucon cannot 'follow' him, i.e. is not equipped to understand his meaning — Wayfarer

Socrates, as you quote, says:

the very truth, as it appears to me

The two terms I put in bold need to be considered. How something appears is not the same as noesis. What appears to him may not appear that way to someone else. There is no such difference or ambiguity when it comes to seeing the Forms themselves. It not a matter of how they appear to me or you or Socrates.

The footnote to this remark is that Socrates will not insist that he perceives rightly, as to do so would be dogmatic. — Wayfarer

I don't know whose opinion that is, but the term itself, from the Greek, means opinion. If Socrates does not want to dogmatic then he does not want to insist that his opinion is true. If that is what the note means then I agree. It makes no sense to claim that if he knows the truth but does not want to insist on the truth.

At any rate, the following passages — Wayfarer

Right before those passages he say:

And may we not also declare that nothing less than the power of dialectics could reveal this, and that only to one experienced in the studies we have described, and that the thing is in no other wise possible?

Two points. Glaucon is not experienced in dialectic and so is merely going along with what Socrates says. He has no understanding of it. Second, he does not say that the power of dialectic does reveal this. Dialectic is not some magic power that transforms speech and thought into noesis.

To deny this is to deny the possibility of the knowledge of the forms, and of the form of the Good, which is fundamental to the entire enterprise .. — Wayfarer

Yes, that is the point. It should be noted that talk of the Forms is conspicuously absent in the Theaettetus, a dialogue about knowledge. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI think your reading is tendentious, I'm sorry. Socrates is saying that the knowledge of 'what things really are' is attained 'by dialectic' i.e. by philosophy, and that Glaucon can't follow this, because he's not sufficientily trained or insightful to do so.

Wayfarer

26.1kI think your reading is tendentious, I'm sorry. Socrates is saying that the knowledge of 'what things really are' is attained 'by dialectic' i.e. by philosophy, and that Glaucon can't follow this, because he's not sufficientily trained or insightful to do so. -

Fooloso4

6.2kFooloso4 I think your reading is tendentious, — Wayfarer

Fooloso4

6.2kFooloso4 I think your reading is tendentious, — Wayfarer

Well, I could point to the work of various highly regarded scholars whose reading too is what you would regard as tendentious, but I never met a Platonist who was persuaded by such arguments, with one exception, That exception is me. Plato is deep enough to allow for differing interpretations.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum