-

ernestm

1kPlato held that only a few wise philosophers could infer concepts like 'justice' intuitively. The far greater number of people (including lawyers) only know them as tenuous shadows in a cave, over which they bicker as to their shape. But they can never really decide, because the shadows are not only all that they can see, but even more crucially, they themselves think the shadows are all there is.

ernestm

1kPlato held that only a few wise philosophers could infer concepts like 'justice' intuitively. The far greater number of people (including lawyers) only know them as tenuous shadows in a cave, over which they bicker as to their shape. But they can never really decide, because the shadows are not only all that they can see, but even more crucially, they themselves think the shadows are all there is.

Only the philosopher knows that the shadows are mere ephemera in a cave of ignorance. Above the cave, in the true light of goodness, ideas are the real natural things, which are "ideal forms." From the ideal forms, the light of goodness casts shadows as pure ideas, like triangles and squares. But most people never see that, and just sees shadows of artificial things, such as living beings and dead objects, which illuminated by the element of fire. The fire's flickering light casts shadows of artificial things onto the cave wall, which is all that most can see. The actual form of the real idea is unknown and unimaginable to those bickering in the caves. If one attempts to show the deluded the actual truth, it is so blinding to them, they can only turn away from it. Instead, they sneer and ridicule those who are able to see the pure ideas and ideal forms from the darkness of the cave, where they shackled like slaves by their own lack of will to seek greater understanding.

"At first, when any of them is liberated and compelled suddenly to stand up and turn his neck round and walk and look towards the light, he will suffer sharp pains; the glare will distress him, and he will be unable to see the realities of which in his former state he had seen the shadows; and then conceive someone saying to him, that what he saw before was an illusion, but that now, when he is approaching nearer to being and his eye is turned towards more real existence, he has a clearer vision, what will be his reply? And you may further imagine that his instructor is pointing to the objects as they pass and requiring him to name them, will he not be perplexed? Will he not fancy that the shadows which he formerly saw are truer than the objects which are now shown to him? ...Until the person is able to abstract and define rationally the idea of good, and unless he can run the gauntlet of all objections, and is ready to disprove them, not by appeals to opinion, but to absolute truth, never faltering at any step of the argument--unless he can do all this, you would say that he knows neither the idea of good nor any other good; he apprehends only a shadow, if anything at all, which is given by opinion and not by science--dreaming and slumbering in this life, before he is well awake here, he arrives at the world below, and has his final quietus. - Republic, Plato (Athens, ~380 BCE).

The problem of Plato's cave is, unless people can understand concepts as existing independently in a domain of mind, it is not only impossible to argue about it, but as Plato writes, painful to do so for both parties. In philosophy, the full theory of the Platonic idea of form is an issue for epistemology (the nature of knowledge) in metaphysics, and too complex for this short essay. The underlying point is that those who cannot understand further (or believe that understanding is illusory) regard philosophy as something like the arcane magic. To the common person, philosophy is akin to the most a Cro-Magnon could understand of an automobile's functioning. So at this point, many people's comprehension ends. They are incapable of understanding something more than the shadows.

When asked to explain how a philosopher knows the true forms of ideas, Plato stated that some nonetheless strive to see the light, after which the truth is known to that philosopher intuitively, but only some people have the intuition. The ability to express that knowledge is a skill, but no matter how much people work on it, they cannot improve their knowledge if they are not natively endowed with the insight.

Often this idea of how truth is known is conflated with the issue of whether platonic forms exist, or whether philosophers should actually be the rulers of government. Really there are separate issues. Is it true that only a few people are capable of reason, as Plato says? Are there really philosopher kings?

-

Wayfarer

26.2kIs it true that only a few people are capable of reason, as Plato says? Are there really philosopher kings? — ernestm

Wayfarer

26.2kIs it true that only a few people are capable of reason, as Plato says? Are there really philosopher kings? — ernestm

That's a very interesting post Ernest. I'm reading a popular account of Plato and Aristotle, received for a Christmas gift, The Cave and the Light: Plato Versus Aristotle, and the Struggle for the Soul of Western Civilization, Arthur Herman, which canvasses some of these issues. (Not a deep book, but written in a novelistic style which is at least easy to read.) As Herman points out, Plato had a very dim view of politics generally, not to mention the arts and poetry. Aristotle was far more pragmatic, and his philosophy as adapted by the Romans is still highly influential in Western civic culture (as indeed it deserves to be!) Plato's ideal republic was, even in his own mind, not really a template for an actual working model but (typically of Plato) an ideal to which an actual society could only ever aspire.

WIth respect to the 'parable of the Cave' - I think the thing which is almost universally overlooked nowadays is that Plato really was a mystic. Of course the word 'mystic' is bandied about nowadays as a universal moniker for all kinds of nonsense, but the dictionary definiton of the term is 'an initiate into the Mystery Schools' - which Plato actually was. But mysticism has been largely redacted out of many of the accounts of Platonism in the intervening centuries which grossly undermines the meaning of such passages as the Allegory of the Cave.

I think the allegory of the Cave denotes the attainment of a kind of noetic illumination or supreme insight into the intelligible order of the Cosmos. The philosopher 'ascends' through the arduous process of reason (and also askesis) whereby he attains the vision of the Good, which is barely sought, let alone seen, by the mass of men (the hoi polloi).

The problem is that this understanding doesn't really even have an analogy in modern or scientific thinking. The last real proponents of such an attitude were arguably the Cambridge Platonists (e.g. Ralph Cudworth) who are barely known today (although there are always some Platonists, or those with Platonist tendencies, amongst mathematicians, for fairly obvious reasons).

The problem of Plato's cave is, unless people can understand concepts as existing independently in a domain of mind, it is not only impossible to argue about it, but as Plato writes, painful to do so for both parties. — ernestm

I feel that is because those who haven't undergone that philosophical ascent simply don't know what to make of it, or how to interpret it. I have noticed that the near-universal tendency with respect to Platonic realism, is to ask 'where' is this 'ghostly domain' in which numbers and the forms are 'located'. And that is because of the habitual extroversion of the natural sensibility - we are so instinctively attuned to the sensory domain, that we can only picture such ideas in terms of 'places' and 'locations'. The kind of intuitive understanding of the nature of concepts that animated ancient philosophy is mainly lost nowadays - it has virtually died out in Western culture (There's a very interesting passage in the Cambridge Companion to Augustine which outlines Augustine's account of the nature of intelligible objects which gives an idea of the ancient notion of 'intelligibility' - one very different to our own.)

But in any case, the upshot is that when Platonism uses the word 'reason', it means something very different to what modern science means by it. The Greek rationalist tradition was 'religious' in a way that modern naturalism can't be (and different again to the Hebrew religiosity that undelies the Bible). It consisted of insight into the underlying order of the Cosmos, whereas nowadays reason is exclusively tethered to what can be quantified mathematically and demonstrated empirically, bracketing out the aesthetic and ethical dimensions which were an integral aspect of the Platonist vision. -

TheMadFool

13.8kIs it true that only a few people are capable of reason, as Plato says? Are there really philosopher kings? — ernestm

If Plato thinks only philosophers should be kings then he probably didn't have any idea of democracy.

In a democracy, rule by the people, its the entire population, not just its leaders, that needs to be philosophers. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kWhen asked to explain how a philosopher knows the true forms of ideas, Plato stated that some nonetheless strive to see the light, after which the truth is known to that philosopher intuitively, but only some people have the intuition. The ability to express that knowledge is a skill, but no matter how much people work on it, they cannot improve their knowledge if they are not natively endowed with the insight. — ernestm

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kWhen asked to explain how a philosopher knows the true forms of ideas, Plato stated that some nonetheless strive to see the light, after which the truth is known to that philosopher intuitively, but only some people have the intuition. The ability to express that knowledge is a skill, but no matter how much people work on it, they cannot improve their knowledge if they are not natively endowed with the insight. — ernestm

"To see the light" is a reference to the part of the allegory in which "the good" itself is represented. We must ensure that "the good" is held in distinction from "the idea of good". The good is said to make the intelligible objects intelligible, just like the sun makes the visible objects visible. It is important to apprehend "the good" which lies behind the intelligible objects, because this is what produces the knowledge that the shadows are merely shadows. Without the good, there is no distinguishing the shadows from the objects themselves, and there is much confusion, just like if we didn't apprehend the sun we wouldn't necessarily see shadows as shadows. By pointing out the sun, then all of a sudden that the shadows are shadows becomes highly intelligible.

That is why seeing the light is like a massive revelation which instantly makes sensible objects as shadows, highly intelligible. When the good is apprehended then instantly one can distinguish the intelligible objects from the shadows of these objects. It then becomes intuitive for that person to approach all of reality, in this way, to distinguish between intelligible objects and their representations, the shadows, which are sensible objects.

I do not believe that it is the case that one must be "natively endowed with the insight". What is the case, is that one must "see the light". Plato has probably led millions of people to see the light. Every human being is endowed with the capacity to see the light, one must simply be shown the light, and accept the "Truth". Once this revelation has occurred, the power of it is so strong. Not only does one see clearly the distinction between objects and the shadows, but the necessity that all shadows must have an object which creates the shadow.

This is the "Truth" which is revealed when one sees the light. All sensible objects are of the nature of a shadow, and behind that shadow is necessarily an intelligible object, which in conjunction with "the good", creates the existence of the sensible object, as a shadow of the intelligible object. Without apprehending the good, we are the prisoners of the cave, seeing the sensible objects (shadows) as if they are real, independent objects. After apprehending the good, it becomes highly evident that the sensible objects, and entire sensible world, are dependent upon intelligible objects for their existence. -

Ralph LutherAccepted Answer

5...Until the person is able to abstract and define rationally the idea of good, and unless he can run the gauntlet of all objections, and is ready to disprove them, not by appeals to opinion, but to absolute truth, never faltering at any step of the argument--unless he can do all this, you would say that he knows neither the idea of good nor any other good

Ralph LutherAccepted Answer

5...Until the person is able to abstract and define rationally the idea of good, and unless he can run the gauntlet of all objections, and is ready to disprove them, not by appeals to opinion, but to absolute truth, never faltering at any step of the argument--unless he can do all this, you would say that he knows neither the idea of good nor any other good

For me the most important word here is "until". It means, that there is a process to be able to the light, the truth, or the good. Probably the most complicated process a human can dare to do. Immanuel Kant has most prominent written: "sapere aude!" Dare to think! And with it tried to describe the first step to enlightenment not only for one single agent, but for whole societies as well.

I therefore think a philosopher king is a sort of teacher. Someone who will guide despite the initial confusion and rejection by his peers.

Should such a King govern? Well govern comes from latin gauberare and means to control, rule and guide! I don't see why not? No intelligent man can hope to govern a sufficient complicated system on his own. And States and countries are just that, complicated systems. So a philosopher king needs to find help to so. Therefore guide other to position in wich they are able to.

A true Philosopher King is therefore someone who aspires to ensure the means of enlightenment, regardless of his own political office. -

ernestm

1kNo, that was not my question.

ernestm

1kNo, that was not my question.

My question was whether only some people are able to see the light.

It is my experience with those interested in platonic philosophy that it usually takes several repetitions of a question before it is actually understood, so dont worry about it. -

Ignignot

59Is it true that only a few people are capable of reason, as Plato says? Are there really philosopher kings? — ernestm

Ignignot

59Is it true that only a few people are capable of reason, as Plato says? Are there really philosopher kings? — ernestm

Let's imagine that Plato wasn't a "great name" in our culture like Shakespeare or Newton. Let's imagine that a community college professor (perhaps an adjunct) is telling his students that only a tiny minority of human beings are in possession of this most important faculty. Would his students believe him? Maybe their parents are well-paid doctors and they are in community college because they flunked out of a more expensive place, having worried too much about pop culture, drinking, and getting laid. Would this not sound like the usual religion of the less successful resentful of how the world is run? (I don't take worldly success as a religion personally, but it has some undeniable, unambiguous virtues).

Only a few people have this "Reason" thingy. Only a few people get into Heaven. Only a few people have "it" in the arts. Of course Plato implicitly presents himself not only a philosopher king but as the king of philosopher kings, the inventor of philosopher kings. It's almost trivial that an intellectual type thinks that he and the few who agree with him are the Real Deal as a opposed to the deficient without the Light. This is not to say that there is no Reason or Light to be had. That would itself be a marketable Darkness Visible. Have you watched Going Clear? I respect Plato more than LRH, obviously. But at least in terms of their personalities as writers they seem to be of a similar type. They know the Secret that will finally save and ennoble humanity. Who doesn't want this gig? And who ever took the notion of philosopher king or "clear" seriously that didn't immediately see this royal status as possible for themselves with just a little work? On the other hand, it's such a beautiful dream that it'd be sad to have never dreamed it. -

ernestm

1kI agree. However it is clearly the case that many people do not experience this revelation, and it remains unclear what factor causes some to understand Plato, and others to sneer at him. There is evident a strong dichotomy on that.

ernestm

1kI agree. However it is clearly the case that many people do not experience this revelation, and it remains unclear what factor causes some to understand Plato, and others to sneer at him. There is evident a strong dichotomy on that. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kI believe it is a certain philosophical attitude, which is described in the character of Socrates. It's a type of open-mindedness, a healthy respect for the unknown, and an unwillingness to quit looking for strong principles to provide support for any knowledge. The majority of individuals are groomed by society, unquestioning of the principles which are fed to them. They develop their own personal body of knowledge, to the extent that it is needed to live their lives within their societies, and they go on their way, doing just that. They have no desire, will, or need, to question the principles which they are taught, because that knowledge allows them to live a happy and satisfying life.

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kI believe it is a certain philosophical attitude, which is described in the character of Socrates. It's a type of open-mindedness, a healthy respect for the unknown, and an unwillingness to quit looking for strong principles to provide support for any knowledge. The majority of individuals are groomed by society, unquestioning of the principles which are fed to them. They develop their own personal body of knowledge, to the extent that it is needed to live their lives within their societies, and they go on their way, doing just that. They have no desire, will, or need, to question the principles which they are taught, because that knowledge allows them to live a happy and satisfying life.

Some though, might find things difficult to understand, perhaps the person's mind wanders in school, not developing a desire to learn the principles being taught. Perhaps some well-accepted principles may appear inconsistent or contradictory to that person, so the person's mind just can't adapt to them. Remember, Socrates lived in a society with an abundance of sophistry. The sophists would tech you, for a fee, but Socrates found their principles to be unsound. So what exactly were the sophists teaching?

Notice that what is evident is a certain degree of dissatisfaction in what is being taught. This is a dissatisfaction with the state of society, the societal norms. If that dissatisfaction exists, and one turns to reading Plato, then the whole realm of skepticism is opened up for that person. All sorts of unjustified principles are put forward by characters claiming that it is the truth, and most of these, being moral principles, are very relevant even today. Then the dissatisfaction of the person is validated, the person is not necessarily a societal misfit. So the person who has approached Plato with that dissatisfaction for what is being taught, may find a real, warranted place, a therefore satisfaction, in questioning the soundness of the principles being taught. Others just sneer at the idea that the principles being taught might not be sound. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9k

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9k

Consider that in The Republic somewhere, Plato says that the same individual who is capable of doing great harm to society is also capable of doing great good to society. We might say that this person has potential, and potential is power, which might be turned toward good or evil. Some of this power is attributable to the person's circumstances, but a large part of this potential may be attributable to the person's motivation to act, ambition, spirit, or passion. So if you take what I said about a person's dissatisfaction, and consider that this dissatisfaction provides motivation to act, then you can see how this ambition might be turned toward great harm or great good, depending... -

Chany

352

Chany

352

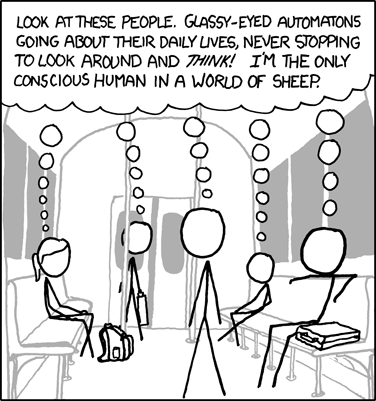

I think you are missing my point. My point is that everyone thinks that they are the special one who "gets" it. They get the world and how it works. Further, they think everyone else (sans a small group of people that the person is a part of) misses the mark and has fallen. Everyone fancies themselves the philosopher king, or, at least, better than the masses (and, yes, this applies to the people like myself).

However, everyone has psychological pitfalls that they fall into regarding their beliefs. Sometimes, they are obvious in some people: people who hold their beliefs with a cult-like attitude. However, everyone has these pitfalls and everyone falls into them; if you say you do not, you are lying. So, yes, it might be true that some people have problems properly examining issues. They might need help and easing to overcome and get around their psychological hurdles, and some may be effectively closed off from external human interference and nothing we can do can change that. However, everyone has the potential to overcome their hurdles and reach something much better.

Of course, there are probably people who are naturally more intelligent then others, but we have no way of knowing the scope of this, so it is kind of moot point to discuss. -

ernestm

1kNo, actually, Plato did not say that either. He said true philosophers are very aware of how much they do not know, and the amount they know that they do not know actually increases as they get older. Or us, promouns are not as flexible in English as they are in Greek which also has the benefit of the middle voice for such statements.

ernestm

1kNo, actually, Plato did not say that either. He said true philosophers are very aware of how much they do not know, and the amount they know that they do not know actually increases as they get older. Or us, promouns are not as flexible in English as they are in Greek which also has the benefit of the middle voice for such statements. -

yazata

41"lf plato thinks only philosophers should be kings then he probably didn't have any idea of democracy."

yazata

41"lf plato thinks only philosophers should be kings then he probably didn't have any idea of democracy."

--"TheMadFool"

I think that Plato knew about democracy since Athens where he lived was (at times) the prototypical democracy, ruled by its citizens physically gathered in an assembly.

In the Republic at least, Plato was an opponent of democracy which he believed was rule-by-the-rabble. What he wanted to do was restore the older oligarchical idea of rule by an aristocracy, except this time not a warrior-aristocracy but an aristocracy of intellectual merit (defined in his rather transcendent terms, of course).

Hence rule by philosophers. Those who habitually think in abstractions, those able to intuit the pure Forms of things, particularly the highest Form of the "Good".

It's basically the same dichotomy that we see creating no end of stresses and strains in Europe and the United States today, in the political tension between the will of the people who want to rule themselves and make their own decisions (the ideal of democracy, often dismissed as 'populism') on one hand, and rule by a class of supposedly superior elites in the capital on the other, composed of university professors, scientists, government officials, business leaders, celebrities and journalists (the 'authorities', those supposedly best qualified to lead everyone else). . -

ernestm

1kIn the Republic at least, Plato was an opponent of democracy which he believed was rule-by-the-rabble. What he wanted to do was restore the older oligarchical idea of rule by an aristocracy, except this time not a warrior-aristocracy but an aristocracy of intellectual merit (defined in his rather transcendent terms, of course). — yazata

ernestm

1kIn the Republic at least, Plato was an opponent of democracy which he believed was rule-by-the-rabble. What he wanted to do was restore the older oligarchical idea of rule by an aristocracy, except this time not a warrior-aristocracy but an aristocracy of intellectual merit (defined in his rather transcendent terms, of course). — yazata

I think that's very well said ) -

RegularGuy

2.6kIs it true that only a few people are capable of reason, as Plato says? Are there really philosopher kings? — ernestm

RegularGuy

2.6kIs it true that only a few people are capable of reason, as Plato says? Are there really philosopher kings? — ernestm

i went to law school for a little over a semester (couldn't stand it, started getting deeply disturbed by the education and the people it attracted), but my Property Law professor said that judges are the closest beings to philosopher kings in our society. I would argue that that is only the case in the Supreme Court and maybe the respective state Supreme Courts. What do you think? -

ernestm

1kI would argue that that is only the case in the Supreme Court and maybe the respective state Supreme Courts. What do you think? — Noah Te Stroete

ernestm

1kI would argue that that is only the case in the Supreme Court and maybe the respective state Supreme Courts. What do you think? — Noah Te Stroete

I only know one state supreme court judge, so I cannot answer that. I can say, having share the empirical reasoning behind the natural rights in the constitution for five years now, that there is not one American alive so far who has modified any intuitive beliefs as to their self-oriented entitlements when confronted with contrary reasoning, no matter how extensive, succinct, or undeniable it is. -

Drek

93That's weird that Plato wanted an intellectual round table. Intelligent people do dumb things too. If he were alive today would he still believe that I wonder. Some people are good at using reasons for bad or to self-justify... an overly complicated child sometimes. We still have emotions and intuition to weigh. Going into high order makes you a hypocrite because you can't please them all. Wouldn't two intelligent and reasonable people disagree... it happens... so here we are.

Drek

93That's weird that Plato wanted an intellectual round table. Intelligent people do dumb things too. If he were alive today would he still believe that I wonder. Some people are good at using reasons for bad or to self-justify... an overly complicated child sometimes. We still have emotions and intuition to weigh. Going into high order makes you a hypocrite because you can't please them all. Wouldn't two intelligent and reasonable people disagree... it happens... so here we are.

Maybe we need an all-rounded person with many life experiences? Not just one desirable trait. A multi-dimensional person that balances logic, emotion, and intuition, Been exposed to arts and science, has been exposed to most opportunities society has to offer. A person of the people... -

TheMadFool

13.8k

A king might choose to be a philosopher but the converse is not true.

Power needs to be checked and wisdom is the best tool for that.

Wisdom checks itself. -

Fooloso4

6.3kI take a very different view of what Plato was up to. This is, however, not an idiosyncratic view. There are well regarded scholars whose work led me to this.

Fooloso4

6.3kI take a very different view of what Plato was up to. This is, however, not an idiosyncratic view. There are well regarded scholars whose work led me to this.

What is often overlooked is the difference between the Socrates who knew that he did not know and the Socrates of the Republic who speaks of knowledge of the whole. One key to reconciling the difference is the banishment of the poets from the Republic. Their myths are replaced by a philosophical poesis. When asked Socrates is circumspect but clear in stating that he does not actually have knowledge of the Forms:

"You will no longer be able to follow, my dear Glaucon," I said, "although there wouldn't be any lack of eagerness on my part. But you

would no longer be seeing an image of what we are saying, but rather the truth itself, at least as it looks to me. Whether it is really so or not can no longer be properly insisted on. But that there is some such thing to see must be insisted on. Isn't it so?" (533a)

The truth as it looks to him may not be the truth, and he is not insisting that it is. But he insists that there is “some such thing to see”. What he shows us is a likeness of what the beings must be, that is, an image. He too is a poet, literally a maker. The Forms are, ironically, images. Those who read Plato and think that they have ascended the cave because the Forms, the eidos, the things themselves as they are in themselves, have been revealed, are simply seeing new images on the cave wall, images created by Plato.

What should not be overlooked is that the training of the guardians is primarily in the development of moderation - sophrosyne. Those who are picked to advance to the study of philosophy will be those who not only have the requisite intelligence but the requisite temperament.

Maybe we need an all-rounded person with many life experiences? — Drek

During the discussion of who would make the best judges Socrates suggests that it would be those who have criminal experience, for they would be better able to recognize injustice than those who have not been exposed to it. -

Drek

93

Drek

93

Yeah, if you've been harmed, you know damn well what is right or wrong. Thanks for your interpretation and analysis! If I had to choose a philosopher, Socrates seems to be the principled one... just a scant understanding. He also was the only to die for what he stood for. Could be wrong but everything is a learning experience.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum