-

Janus

17.9kThe issue I pointed to earlier in the thread, is the nature of the assumed "mind-independent world". This world is not necessarily external, it might be internal, and we simply model it as being external. — Metaphysician Undercover

Janus

17.9kThe issue I pointed to earlier in the thread, is the nature of the assumed "mind-independent world". This world is not necessarily external, it might be internal, and we simply model it as being external. — Metaphysician Undercover

The mind-independent world is necessarily thought as being external to the mind (and body). Of course, there can be no mind-independent thought of the mind-independent world; that goes without saying

The experience consists of all the necessary elements. If some of it is internal and some is external, then the experience can rightly be called neither, for it is not the sort of thing that has such spatiotemporal location. — creativesoul

If there is no meaningful distinction between internal and external, then how can we determine that some is external (or internal)? Usually the idea of something external is the idea of something that can be perceived as being external to the body by the bodily senses and that is what you have relied on to determine that

They are being emitted/reflected by something other than our own biological structures. Thus, the meaningful experience of seeing red leaves requires leaves that reflect/emit those wavelengths. Leaves are external to the individual host of biological machinery. — creativesoul

So, the leaves and light are external, and the biological machinery is internal. It takes both(and more) to have a meaningful experience of seeing red. — creativesoul

The experience consists of all the necessary elements. If some of it is internal and some is external, then the experience can rightly be called neither, for it is not the sort of thing that has such spatiotemporal location. — creativesoul

If the experience is considered to be an affect of the biological machinery insofar as it is the biological machinery that experiences red and not the leaves or the light, then it follows that we are thinking of the experience, by your own definitions, as internal. Of course it needs the stimulus of external elements (light and leaves) but it does not follow that the experience is both internal and external on that account, Of course if you define experience as the whole process, then of course it, tautologically, is both internal and external, so these are just different ways of speaking, different ways of conceptually dividing and/ or sorting things. -

Isaac

10.3kPerhaps we can agree that in general theoretical empirical orientations do impact on metaphysical

Isaac

10.3kPerhaps we can agree that in general theoretical empirical orientations do impact on metaphysical

positions. While quantum physics doesn’t necessarily threaten realism as a whole , it does seem to be incompatible with naive (direct) realism. — Joshs

Yes, we can agree there. I think the empirical observations from cognitive science also support that view (though with the caveat that I'm still not sure I've understood what a direct realist really wants to say).

That there are steps in the process of perception seems obvious, without any more science than just everyday experience. Cognitive science has confirmed the extent and the method.

Where I think cognitive science has produced surprising results for the metaphysics of conscious experience, is in showing that, if we accept a disconnect between object and internal response (be that representational or enactive continual re-creation), then we have to similarly accept a disconnect between the impression we now have of what happened (why I said "cup" when I saw that cup), and what actually just happened.

To be consistent, the indirect realist cannot claim stages represent indirectness when creating the model/enacting the narrative, but then deny they do that when talking about one's memory of such an experience. -

Isaac

10.3kyou divorce the biological machinery from the experience of seeing red when you claim that the machinery "mediates" the experience. — creativesoul

Isaac

10.3kyou divorce the biological machinery from the experience of seeing red when you claim that the machinery "mediates" the experience. — creativesoul

You might have to unpack that a little. I'm not really sure what you might mean by 'divorce'. Is mediating something not 'part of'? The mediator in a discussion is part of the discussion, no? -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThe mind-independent world is necessarily thought as being external to the mind (and body). — Janus

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThe mind-independent world is necessarily thought as being external to the mind (and body). — Janus

As I explained earlier, external and internal are spatial terms. We tend to set, or assume a boundary between mind (and body) and the external, but we assume no such boundary between mind (and body) and the internal. Why not? The activities of the mind (and body) are intermediate between the proposed external world, and the internal soul. If the external world is supposed to lie on the other side of a boundary, then for consistency sake, we ought to assume that the internal world also lies on the other side of a boundary.

If we take a sphere, we assume an external circumference, as a defining boundary. The dimensionless "point" at the centre of the sphere though, is indefinite due to the irrational nature of pi. To properly understand the reality of "the centre", as a proposed non-dimensional point with a specific location in a spatial entity, we need a defining boundary between the dimensional and the non-dimensional. In mathematics it is represented by infinitesimals. In practise, this is the boundary between the dimensional (external), and the non-dimensional (internal). But if we propose a boundary between human activity and the external, we need also to propose a boundary between human activity and the internal.

So if we proceed from here to ask which is the real "mind-independent world", the external or the internal, there is no necessity to conclude that it is the external. And this is why dualism is so appealing, it allows us to conceive of the reality of both, the internal and external "mind-independent" worlds. And the supposed "interaction problem" is left without bearing, because the mind (and body) is the realm of interaction. -

Hello Human

195Imagine an air traffic controller looking at flashes of light on a circular screen and lots of numbers. Is the air traffic controller perceiving the planes he has so much information about and whose behaviour he can predict and direct? No. The air traffic controller is acquiring lots of true beliefs about some planes, but he is not perceiving them.

Hello Human

195Imagine an air traffic controller looking at flashes of light on a circular screen and lots of numbers. Is the air traffic controller perceiving the planes he has so much information about and whose behaviour he can predict and direct? No. The air traffic controller is acquiring lots of true beliefs about some planes, but he is not perceiving them.

Or perhaps a better example might be a pilot. Pilots do not have to look out the window to fly the plane and navigate the landscape, as they have enough information from their instruments. But when the pilot is looking at the instruments they are not perceiving the landscape (unlike when they look through the window at it).

There is clearly a difference then between acquiring one's awareness via means that in no way resemble what one is becoming aware of and via means that do. And it is in the latter case that we can be said to be 'perceiving'. Or at least, that a necessary condition for perception has been met (resemblance isn't sufficient). — Bartricks

Ok I agree with with this. But still, I'm not sure of what is meant exactly by "perceiving". I'm also not sure of how this is related to the thesis that the world is made up of sensations. -

Hello Human

195I think resemblance is a sensation. I sense x to resemble y. There is a resemblance sensation experienced when I sense or think about x and y. And by hypothesis, in order for that sensation of resemblance to be of actual resemblance, it would need to resemble it (otherwise I would not be perceiving it). — Bartricks

Hello Human

195I think resemblance is a sensation. I sense x to resemble y. There is a resemblance sensation experienced when I sense or think about x and y. And by hypothesis, in order for that sensation of resemblance to be of actual resemblance, it would need to resemble it (otherwise I would not be perceiving it). — Bartricks

Ok I see.

And only a sensation can resemble a sensation (a truth of reason) — Bartricks

This point seems to come back often. Is there any way for someone to accept it other than viewing it as "a truth of reason" ? -

Mww

5.4k

Mww

5.4k

I suppose. I really don’t have a trust-with-my-life kinda thing for this question. I’m stuck between what appears to be the intrusion of anti-narrative, OLP philosophy in the analytic tradition onto theory-laden speculative metaphysics in the continental tradition. That is, regarding the latter, a simple thought vs a complex thought is merely a matter of content, any thought at all being nothing more than a “cognition by means of conceptions”. With regard to the former, on the other hand, the distinction between simple vs complex thought seems to be a matter of form, one only possible with, the other possible without, words.

I guess I fail to understand why it shouldn’t be the case that an aggregate of simple thoughts possible without words, couldn’t become a complex thought, which then would necessarily itself be without words. Maybe the simple/complex distinction is merely a condition of time. Maybe the longer there is a simple thought, the more complex it becomes.

But then....time itself, being a mere condition for, cannot be considered a content of, so we are left with the notion that the time of just indicates a time to adjoin an aggregate of simples. Which is probably where the notion of intentionality...an altogether post-modern precept...originates, insofar as even if time to amend is enabled, there is nothing about the pure intuition of time that demands its fulfillment.

But then....isn’t that exactly what understanding is, at least from the meta-narrative continental POV? The most thorough combination of amendable conceptions possible? Such that there can be no contradiction in the cognition that follows from it, the combining making time to combine, necessary?

I think I shall remain content that a complex thought doesn’t need words any more than does a simple thought. I affirm that complex thoughts are indeed possible, but deny the necessity of language as the ground of their possibility. -

Bartricks

6kOk I agree with with this. But still, I'm not sure of what is meant exactly by "perceiving". I'm also not sure of how this is related to the thesis that the world is made up of sensations. — Hello Human

Bartricks

6kOk I agree with with this. But still, I'm not sure of what is meant exactly by "perceiving". I'm also not sure of how this is related to the thesis that the world is made up of sensations. — Hello Human

Because unless our sensations resemble the world they are telling us about - and tell us about it in that way - they will not constitute perceptions of the world.

We do perceive an external sensible world.

If our sensations were merely providing us with information about the world, then we would not be perceiving the world by means of them (that was the point the air traffic controller example was designed to illustrate - acquiring information about a matter is not the same as perceiving it).

So, as we do perceive an external sensible world, our sensations must resemble it.

Sensations can only resemble other sensations.

From this it follows that the sensible world that we perceive by means of our sensations is itself made of sensations.

And that, in combination with the self-evident truth that sensations can only exist in a mind, gets us to the conclusion that the external sensible world is made of the sensations of another mind. -

Bartricks

6kOk I see. — Hello Human

Bartricks

6kOk I see. — Hello Human

But what I did there is simply appeal to the argument for idealism. That is, I simply applied the basic argument for idealism to resemblance itself.

The argument for idealism - the main argument - goes via certain self evident truths of reason, namely that a) sensations can only resemble other sensations and b) that sensations can exist in minds and minds alone.

This point seems to come back often. Is there any way for someone to accept it other than viewing it as "a truth of reason" ? — Hello Human

All evidence for anything amounts to an appeal to a self-evident truth of reason.

All examples do is excite acknowledgment of the self-evident truth of reason.

But in the case of sensations, even within the domain of sensations, one type of sensation seems only to resemble other sensations of the same type (though whether this is actually true is not essential to the claim that sensations can only resemble other sensations).

Consider texture and sight. Do colours have a texture? That is, can you 'feel' what colour something is without any recourse to a visual impression?

No, obviously not. Indeed, the very notion seems confused. Colours are essentially seen, not felt. That this is so clearly true is a self-evident truth of reason. One cannot see that colours are essentially seen. One can see a colour. But one cannot see that colours are essentially seen. That is a self-evident truth of reason, not something we are aware of sensibly.

By the same token, it seems equally self-evident to reason that nothing can resemble a sensation of any kind except some other sensation. -

creativesoul

12.2kIf there is no meaningful distinction between internal and external... — Janus

That's not what I said.

If the experience is considered to be an affect of the biological machinery insofar as it is the biological machinery that experiences red and not the leaves or the light, then it follows that we are thinking of the experience, by your own definitions, as internal. — Janus

That does not follow from what I've written. It is contrary to it.

Of course it needs the stimulus of external elements (light and leaves) but it does not follow that the experience is both internal and external on that account, Of course if you define experience as the whole process, then of course it, tautologically, is both internal and external, so these are just different ways of speaking, different ways of conceptually dividing and/ or sorting things.

There are different terminological frameworks and methodological approaches used as a means to attempt to take proper account of the same things; each framework and/or approach with their own set of logical consequences as well as explanatory power, congruence with current knowledge, and amenability to evolutionary progression. In this case, we're taking account of the experience of seeing red. Seeing red is a meaningful experience.

We're talking about exactly what sorts of things meaningful experiences are.

Due diligence holds that there are necessary elemental constituents of all meaningful experiences such that all meaningful experiences include them, and if any are removed what remains does not have what it takes. Hence, these basic ingredients are rightfully called the necessary elemental constituents of all meaningful experience. Seeing red is but one.

Seeing red leaves includes leaves that emit/reflect the wavelengths of light we've named "red", a light source, and a creature endowed with certain biological structures capable of not only detecting the light and leaves, but also of somehow isolating and/or picking out the color itself as significant and/or meaningful(attributing meaning to the color). That task(attributing meaning) is successfully performed by virtue of drawing correlations between the wavelengths and something else.

In the complete absence of light and leaves there cannot be any experience of seeing them. In the complete absence of the biological machinery, there cannot be any experience of seeing them. Thus, the experience consists of both internal and external things. It most certainly follows that the experience is neither internal nor external for it consists of elements that are both. -

creativesoul

12.2k...Is mediating something not 'part of'? The mediator in a discussion is part of the discussion, no? — Isaac

1.) Mediation requires a worldview. The biological structures under consideration have none.

2.) The mediator in a discussion is not necessary for the discussion. The biological structures under consideration are necessary for seeing red.

3.) A mediator has the expressed purpose of overseeing and/or governing the conversation to ensure the respective parties successfully reach agreement/consensus through thoughtful negotiation and compromise. The biological structures under consideration are not doing that.

You might have to unpack that a little. I'm not really sure what you might mean by 'divorce'... — Isaac

As above, so below...

4.) Mediators do not mediate themselves. -

Isaac

10.3k

Isaac

10.3k

So the problem is with the term 'mediator'? I'm not wedded to the term, if it's problematic. -

creativesoul

12.2k

Pretty much. As mentioned before in my first reply to you, it's a terminological quibble. However, removing that bit will sharpen the position as well as eliminate any justified objections based upon it, such as I raised and the underlying anthropomorphism. -

creativesoul

12.2k

I'm curious though, does that elimination have consequences regarding whether the red leaves are directly or indirectly perceived?

P.S. For whatever it's worth, the indirect/direct dichotomy and/or debate is neither a necessary nor helpful tool for acquiring understanding of meaningful experience. It can be brushed aside, and ought on my view due to the inherent deficiencies in how they talk about experience itself. -

Janus

17.9kI think I shall remain content that a complex thought doesn’t need words any more than does a simple thought. I affirm that complex thoughts are indeed possible, but deny the necessity of language as the ground of their possibility. — Mww

Janus

17.9kI think I shall remain content that a complex thought doesn’t need words any more than does a simple thought. I affirm that complex thoughts are indeed possible, but deny the necessity of language as the ground of their possibility. — Mww

Fair enough, I suppose. I remain unconvinced that complex abstract thinking is possible without symbolic language. And I don't think this conclusion has anything to do with OLP. I don't at all deny the human imagination's capacity to create complex metaphysical systems, and I don't, like the positivists, count such systems as meaningless or incoherent as such, but I do believe that there is a human propensity to take such systems as presenting literal truths, which I think is the Wittgensteinian point about "language on holiday".

I can't imagine how such complex metaphysical systems of thought would be possible without symbolic language; in other words I don't see how they could be rendered in concrete purely imagistic terms, but I grant that maybe that's a failure of imagination on my part. If someone can explain to me how such a thing could be possible, I'd be very interested to hear it, because I'd love to think that it is possible. It would be a much more interesting world if it was possible.

I think all divisions are contextual; their logic derives from different perspectives we can take due to language and imagination; the different ways we are able to picture things.

I wasn't able to discern any point of disagreement on your part with anything I'd said, so nothing to respond to. -

creativesoul

12.2kI think I shall remain content that a complex thought doesn’t need words any more than does a simple thought. I affirm that complex thoughts are indeed possible, but deny the necessity of language as the ground of their possibility. — Mww

On your view...

Are thoughts about the truth of a sentence considered complex thoughts? Thoughts about what's going to happen next Thursday? Thoughts about which words best describe meaningful experience? Thoughts about language use in general?

All those thoughts are impossible to form, have, and/or hold without words. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k

That some complex thoughts use words does not mean that all complex thoughts use words. -

creativesoul

12.2k

I never said that or otherwise...

The issue - to me - is what sorts of complex thoughts can be formed in the complete absence of language(without words). My objection was to the claim that "a complex thought doesn’t need words any more than does a simple thought." That claim is false as it is written. I gave examples of complex thoughts that most certainly do. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k

Let me explain then. You have provided examples of complex thought which uses words. These examples are insufficient to produce the inductive conclusion "complex thought needs words". You have provided no evidence whatsoever, that complex thought requires words, only evidence that some complex thought uses words. Therefore you do not have the premise required to conclude that this proposition "a complex thought doesn’t need words any more than does a simple thought" is false. You have provided no indication that complex thought needs words. -

Michael

16.8kCan we think without language?

Michael

16.8kCan we think without language?

Imagine a woman – let’s call her Sue. One day Sue gets a stroke that destroys large areas of brain tissue within her left hemisphere. As a result, she develops a condition known as global aphasia, meaning she can no longer produce or understand phrases and sentences. The question is: to what extent are Sue’s thinking abilities preserved?

Many writers and philosophers have drawn a strong connection between language and thought. Oscar Wilde called language “the parent, and not the child, of thought.” Ludwig Wittgenstein claimed that “the limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” And Bertrand Russell stated that the role of language is “to make possible thoughts which could not exist without it.” Given this view, Sue should have irreparable damage to her cognitive abilities when she loses access to language. Do neuroscientists agree? Not quite.

This language system seems to be distinct from regions that are linked to our ability to plan, remember, reminisce on past and future, reason in social situations, experience empathy, make moral decisions, and construct one’s self-image. Thus, vast portions of our everyday cognitive experiences appear to be unrelated to language per se.

But what about Sue? Can she really think the way we do?

While we cannot directly measure what it’s like to think like a neurotypical adult, we can probe Sue’s cognitive abilities by asking her to perform a variety of different tasks. Turns out, patients with global aphasia can solve arithmetic problems, reason about intentions of others, and engage in complex causal reasoning tasks. They can tell whether a drawing depicts a real-life event and laugh when in doesn’t. Some of them play chess in their spare time. Some even engage in creative tasks – a composer Vissarion Shebalin continued to write music even after a stroke that left him severely aphasic.

Some readers might find these results surprising, given that their own thoughts seem to be tied to language so closely. If you find yourself in that category, I have a surprise for you – research has established that not everybody has inner speech experiences. A bilingual friend of mine sometimes gets asked if she thinks in English or Polish, but she doesn’t quite get the question (“how can you think in a language?”). Another friend of mine claims that he “thinks in landscapes,” a sentiment that conveys the pictorial nature of some people’s thoughts. Therefore, even inner speech does not appear to be necessary for thought.

Have we solved the mystery then? Can we claim that language and thought are completely independent and Bertrand Russell was wrong? Only to some extent. We have shown that damage to the language system within an adult human brain leaves most other cognitive functions intact. However, when it comes to the language-thought link across the entire lifespan, the picture is far less clear. While available evidence is scarce, it does indicate that some of the cognitive functions discussed above are, at least to some extent, acquired through language.

Perhaps the clearest case is numbers. There are certain tribes around the world whose languages do not have number words – some might only have words for one through five (Munduruku), and some won’t even have those (Pirahã). Speakers of Pirahã have been shown to make mistakes on one-to-one matching tasks (“get as many sticks as there are balls”), suggesting that language plays an important role in bootstrapping exact number manipulations.

Another way to examine the influence of language on cognition over time is by studying cases when language access is delayed. Deaf children born into hearing families often do not get exposure to sign languages for the first few months or even years of life; such language deprivation has been shown to impair their ability to engage in social interactions and reason about the intentions of others. Thus, while the language system may not be directly involved in the process of thinking, it is crucial for acquiring enough information to properly set up various cognitive domains.

Even after her stroke, our patient Sue will have access to a wide range of cognitive abilities. She will be able to think by drawing on neural systems underlying many non-linguistic skills, such as numerical cognition, planning, and social reasoning. It is worth bearing in mind, however, that at least some of those systems might have relied on language back when Sue was a child. While the static view of the human mind suggests that language and thought are largely disconnected, the dynamic view hints at a rich nature of language-thought interactions across development. -

Mww

5.4kOn your view... — creativesoul

Mww

5.4kOn your view... — creativesoul

In my view.....

......it is preposterous, bordering on the catastrophically absurd, that the totality of that of which I am aware, re: the entirely of my cognitions, requires that I read, write and speak;

......if language developed as a means of simplex expression by a single thinking human subject, or as a means of multiplex communication between a plurality of thinking human subjects, then it is the case language presupposes that which is expressed or communicated by it;

......if language is assemblage of words, and words are the representations of conceptions, and language is the means of report in the form of expression or communication, then language presupposes the conceptions they represent, and on which is reported;

......thinking is cognition by means of conceptions. If language presupposes conceptions, and conceptions are the form of cognitions, and cognition is thinking, then words presuppose thinking.

......that which presupposes cannot be contained in that which is presupposed by it;

.....there is no language in thinking; there is language in only post hoc reports on thinking.

————

If language is so all-fired necessary for the formation of complex thoughts, why did we come equipped with the means for the one, but only for the means of developing the other? Why did we not come equally equipped for both simultaneously, if one absolutely requires the other? The robotics engineer manufactures a machine with pinpoint circuit board soldering accuracy; the toddler has somewhat less accuracy but still understands the distinction between thing-as-object and thing-as-receptor-of object, and the congruency of shape for both, to put a round object in a round hole.

So I come upon a thing, some thing for which I have absolutely no experience whatsoever. Maybe something fell to Earth, maybe I discovered something previously unknown in the deep blue. The modern argument seems to be......I can form no complex thoughts about that new thing, can have no immediate cognition of it, unless or until I can assign words to it. But, being new, which words do I assign if I don’t cognize what the new thing appears to be? What prevents me from calling the new thing by a name already given to an old thing?

And, of course, everything is new at one time or another.

Views: Like noses. Everybody’s got one. -

Hello Human

195Because unless our sensations resemble the world they are telling us about - and tell us about it in that way - they will not constitute perceptions of the world. — Bartricks

Hello Human

195Because unless our sensations resemble the world they are telling us about - and tell us about it in that way - they will not constitute perceptions of the world. — Bartricks

Ok I agree.

We do perceive an external sensible world. — Bartricks

This seems to me like quite the claim to make. Why do you think so ?

If our sensations were merely providing us with information about the world, then we would not be perceiving the world by means of them (that was the point the air traffic controller example was designed to illustrate - acquiring information about a matter is not the same as perceiving it). — Bartricks

:up:

Sensations can only resemble other sensations. — Bartricks

Resemblance in what regard ? What properties are you talking about when you talk about resemblance between sensations? -

Isaac

10.3kFor whatever it's worth, the indirect/direct dichotomy and/or debate is neither a necessary nor helpful tool for acquiring understanding of meaningful experience. It can be brushed aside, and ought on my view due to the inherent deficiencies in how they talk about experience itself. — creativesoul

Isaac

10.3kFor whatever it's worth, the indirect/direct dichotomy and/or debate is neither a necessary nor helpful tool for acquiring understanding of meaningful experience. It can be brushed aside, and ought on my view due to the inherent deficiencies in how they talk about experience itself. — creativesoul

I agree (which I think also answers your first question). The problem with 'direct' and 'indirect', which we're seeing here, is that both require a network model (a model of the nodes so that we could say "these two are right next to one another" (direct), and "these two are separated by intervening nodes"(indirect). But the intervening nodes must, by definition, be indirectly experienced (if they were directly experienced, they would not be intervening nodes). So, by definition, we have to derive our network model by some process other than phenomenological reflection - we've admitted by the very subject of our investigation that we won't notice them by reflecting only on that which we experience.

This isn't a problem for many forms of scientific realism because we can infer nodes from empirical studies of the body and brain which we assume is doing the experiencing.

I can't see how a purely metaphysical approach could possibly infer nodes that we've pre-defined, as being hidden from experience, having, as it does, only that which occurs to our rational minds, as it's data set. -

Michael

16.8kThe problem with 'direct' and 'indirect', which we're seeing here, is that both require a network model (a model of the nodes so that we could say "these two are right next to one another" (direct), and "these two are separated by intervening nodes"(indirect). But the intervening nodes must, by definition, be indirectly experienced (if they were directly experienced, they would not be intervening nodes). — Isaac

Michael

16.8kThe problem with 'direct' and 'indirect', which we're seeing here, is that both require a network model (a model of the nodes so that we could say "these two are right next to one another" (direct), and "these two are separated by intervening nodes"(indirect). But the intervening nodes must, by definition, be indirectly experienced (if they were directly experienced, they would not be intervening nodes). — Isaac

I think that this interpretation places too much focus on the word used to label the metaphysics and not enough on the problem that the metaphysics is trying to solve.

The epistemological problem of perception is: do our ordinary experiences provide us with information about the existence and nature of the external world. Direct realists say that they do "because experience is direct" and indirect realists say that they don't "because experience is indirect".

Rather than quibble over the meaning of "direct" and "indirect" it is best to simply address the underlying problem. If it can be shown that ordinary experiences do not provide us with information about the existence and nature of the external world then experience isn't direct, whatever "direct" is supposed to mean. And I think that this is where the character of the experience is what needs to be considered, and whether or not it makes sense to think of this character as being the character of mind-independent objects.

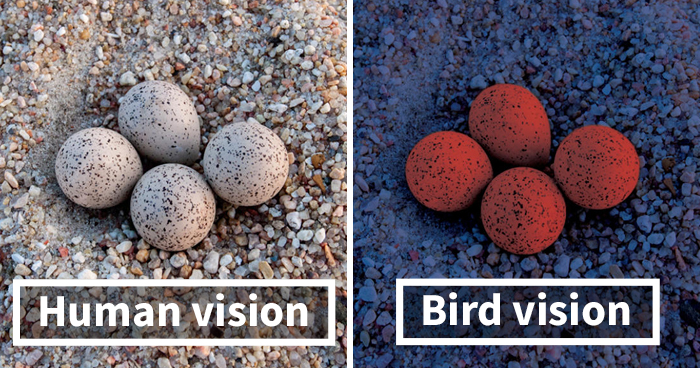

So let's refer back to an image I posted before:

The character of a human's experience is different to the character of a bird's experience. This claim is true whether you want to make sense of this in terms of qualia/sense-data or in terms of Bayesian models, or in terms of something else. If direct realism is true then the mind-independent world is of the same character as one of these experiences. The eggs have the colour either we or the birds see them to have even when not being seen; they're either cream-coloured or they're red-coloured (or we're both wrong and they're some other colour).

This is where we run into the first problem: given that the character of the bird's experience differs from the character of the human's experience, one (or both) of these are "wrong" (in the sense that the mind-independent world isn't of the same character as one (or both) of these experiences). As such, at least one of the experiences isn't direct. The Common Kind Claim then comes into effect; there is no fundamental difference between the nature of a veridical and a non-veridical experience, just as there is no fundamental difference between the nature of a true statement and a false statement. The veracity of the experience (or statement) is determined not by the nature of the experience but by whether or not the facts "correspond" with the experience; the veracity of the experience is independent of the experience.

The second problem is that our best descriptions of the mind-independent nature of the world (things like the Standard Model) do not find that things have visual colours. It finds that they absorb photons of certain wavelengths and emit or reflect photons of other wavelengths, but that's a very different thing to the cream- or red-colour as given in experience and shown in the photo above, hence why different organisms see different colours when stimulated by the same kind of light.

We then seem to have an answer to the epistemological problem of perception: our ordinary experiences do not provide us with information about the existence and nature of the external world. We don't need to get lost in an effectively pointless debate over the words "direct" and "indirect". -

Isaac

10.3kIf direct realism is true then the mind-independent world is of the same character as one of these experiences. The eggs have the colour either we or the birds see them to have even when not being seen; they're either cream-coloured or they're red-coloured (or we're both wrong and they're some other colour). — Michael

Isaac

10.3kIf direct realism is true then the mind-independent world is of the same character as one of these experiences. The eggs have the colour either we or the birds see them to have even when not being seen; they're either cream-coloured or they're red-coloured (or we're both wrong and they're some other colour). — Michael

We're going round in circles. You've still not explained why you think this restriction exists. Why must the hidden state be either cream-coloured, or red-coloured, why can it not be both? we don't know what properties hidden states have (clue's in the name), so you've no grounds at all, as far as I can see, to claim they are such that they can only be one colour at a time.

This is where we run into the first problem: given that the character of the bird's experience differs from the character of the human's experience, one (or both) of these are "wrong" (in the sense that the mind-independent world isn't of the same character as one (or both) of these experiences). As such, at least one of the experiences isn't direct. — Michael

Again, see above.

The second problem is that our best descriptions of the mind-independent nature of the world (things like the Standard Model) do not find that things have visual colours. — Michael

Begs the question. Physics doesn't find what you're prepared to call colours because of the very theoretical commitment we're disagreeing on. I'm perfectly happy to say that "absorb[ing] photons of certain wavelengths and emit or reflect photons of other wavelengths" is what colour looks like when looked at through the machines of the physicists.

our ordinary experiences do not provide us with information about the existence and nature of the external world. — Michael

Then how is that we interact with it so accurately? -

Michael

16.8kWhy must the hidden state be either cream-coloured, or red-coloured, why can it not be both? — Isaac

Michael

16.8kWhy must the hidden state be either cream-coloured, or red-coloured, why can it not be both? — Isaac

If there’s just one possible case where it isn’t both then the point stands.

So you would have to argue that mind-independent objects are every colour that any possible organism could possibly see them to be. Are you willing to commit to that?

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum