-

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

To reiterate, in one version of the argument the indirect realist claims what we see is a model of the tree, while the direct realist says what we do in seeing the tree is to construct a set of neural paths that model the tree. The direct realist would not say that what we see is the model of the tree, but that what we see is the tree, and we see it in modelling it.In fact I think this is a prime example of the problem. The indirect realist will agree with this, and say that this model is a representation of the tree, and that it is this model that (directly) informs our understanding. You appear to be describing indirect realism, but calling it direct realism. — Michael

Yep.Arguing over the semantics of whether this should be called "seeing a tree" or "seeing a model of a tree" is a red herring. — Michael

The Robinson article looks interesting but is paywalled, never to be read. -

Banno

30.6kWittgenstein Philosophical Investigations may be used to give insights into Indirect Realism, including his strong case against the possibility of a private language and his arguing that nobody knows another person's private sensations. — RussellA

Banno

30.6kWittgenstein Philosophical Investigations may be used to give insights into Indirect Realism, including his strong case against the possibility of a private language and his arguing that nobody knows another person's private sensations. — RussellA

This is a misreading of the private language argument. He is not arguing that no one knows antoehr's private sensations, so much as that if there are any private sensations then by that very fact they cannot be discussed.

And yet we do talk about the stuff around us.

Therefore it is not private.

The the private language argument does the opposite of what you suppose. -

Banno

30.6kAs I innately believe in the law of causation, in that every effect has a cause, I therefore believe that there is something that has caused me to perceive a "tree". I don't know what this something is, but I do believe it exists. — RussellA

Banno

30.6kAs I innately believe in the law of causation, in that every effect has a cause, I therefore believe that there is something that has caused me to perceive a "tree". I don't know what this something is, but I do believe it exists. — RussellA

This is the slightly mad bit.

That 'something that has caused me to perceive a "tree'?

It's a tree.

That's what a tree is. -

Michael

16.8kTo reiterate, in one version of the argument the indirect realist claims what we see is a model of the tree — Banno

Michael

16.8kTo reiterate, in one version of the argument the indirect realist claims what we see is a model of the tree — Banno

It’s just another way of talking. It’s like saying that I feel pain rather than saying I feel a knife stabbing me. That sensation of pain is feeling the knife stabbing me. But pain is a property of the experience, a mental phenomena, not a property of the knife, and we do in fact feel pain. There’s no suggestion of a homunculus here. Why it would be any different for sight is lost on me.

Try talking instead about the apple "appearing" smooth. — Banno

Yes, I’ve mentioned this before. There’s something peculiar about sight that I think is more susceptible to direct realist thinking than other senses might be. Does the fact that you would feel cold were you to be placed in the Arctic but that a polar bear doesn’t show either that you can sense the cold that’s there better than the bear, or that you mistakingly sense some cold that isn’t there? Or is it just the case that your body is such that, in such temperatures, you feel cold? I think the latter. And I think that things like colour are no different in principle. It’s just a different mode of experience caused by a different type of stimulus. -

Banno

30.6kWell, since the unobserved tree is "unknowable" and all that, and given that we can still talk about it when our backs are turned to it, why not just keep talking of the "tree"?

Banno

30.6kWell, since the unobserved tree is "unknowable" and all that, and given that we can still talk about it when our backs are turned to it, why not just keep talking of the "tree"?

Not for pragmatic reasons, but because there is no reason to talk otherwise.

(I'm not reaching for pragmatism here, so much as for parsimony). -

frank

19kWell, since the unobserved tree is "unknowable" and all that, and given that we can still talk about it when our backs are turned to it, why not just keep talking of the "tree"?

frank

19kWell, since the unobserved tree is "unknowable" and all that, and given that we can still talk about it when our backs are turned to it, why not just keep talking of the "tree"?

Not for pragmatic reasons, but because there is no reason to talk otherwise.

(I'm not reaching for pragmatism here, so much as for parsimony). — Banno

Yes. But we can stop and gape at the fact that the unobserved tree is unknowable. We'll all agree to never speak of it again after that. -

Janus

18kI hope and trust we are actually talking about the world and not our individual 'images' of the world. — green flag

Janus

18kI hope and trust we are actually talking about the world and not our individual 'images' of the world. — green flag

"The world" is nothing more than the idea of what our individual images and ideas of a world seem to have in common; it is a collective representation. -

Banno

30.6kWhy not? — frank

Banno

30.6kWhy not? — frank

Why?

I think we can make true statements about the unobserved tree, based on our other observations.

So we look at the tree, and see it has three branches, and then turn our backs and decide to prune the middle branch. Even when our backs are turned, I'm quite happy to say that the tree has a middle branch.

This is what we do.

We do not turn our backs and then find ourselves unable to decide which branch to prune.

Of course, instead of pruning the tree one might decide to play at philosophy... -

plaque flag

2.7k"The world" is nothing more than the idea of what our individual images and ideas of a world seem to have in common; it is a collective representation. — Janus

plaque flag

2.7k"The world" is nothing more than the idea of what our individual images and ideas of a world seem to have in common; it is a collective representation. — Janus

You are presupposing in what you say that we all already exist in some (the same) actual world. Where are we supposed to be alive and looking at these screens (our individual images) ? In the intersection of the images on those screens ? That makes no sense.

It's as if you imagine a framework of dreamers who each live in their own secret dimension and yet somehow communicate and negotiate an official shared world, as if we are writing a novel together remotely. But the concept of world, the one that matters, is most basically something like our shared situation. We can be wrong about living on a planet. But we can't be wrong about the possibility of being wrong about something.

The minimal rational assumption is a (shared ) languageworld. Else there is no way to argue and no something to be wrong or right about. -

plaque flag

2.7kHe is not arguing that no one knows antoehr;s private sensations, so much as that if there are any private sensations then by that very fact they cannot be discussed. — Banno

plaque flag

2.7kHe is not arguing that no one knows antoehr;s private sensations, so much as that if there are any private sensations then by that very fact they cannot be discussed. — Banno

:up: -

plaque flag

2.7kOne can never be mistaken about what one sees. — RussellA

plaque flag

2.7kOne can never be mistaken about what one sees. — RussellA

If this is true, it's not a discovery about seeing but only about the grammar of 'see.'

But I don't think it's even simply true, though I understand that philosophers want some word or another for the given about which one cannot be wrong.

This buys certainty at the cost of all significance ? -

Janus

18kWhaever gives rise to the collective representation of a world does so reliably, else there could be no collective representation. That is all we know about the "in itself".

Janus

18kWhaever gives rise to the collective representation of a world does so reliably, else there could be no collective representation. That is all we know about the "in itself".

So, if you read carefully you would see that I am not arguing against a "shared languageworld". -

Isaac

10.3kThere's more to experience than just rational thought. Seeing and feeling and tasting aren't just cases of thinking. — Michael

Isaac

10.3kThere's more to experience than just rational thought. Seeing and feeling and tasting aren't just cases of thinking. — Michael

Why not?

But what does it mean to think that apples are red? — Michael

It means that I'll reach for the word "red" if asked to describe the colour.

You suggested before that to be red is to have a surface that reflects light with a wavelength of 700nm, so to think that apples are red is to think that apples have a surface that reflects light with a wavelength of 700nm? — Michael

Yes, that's right.

How does that make sense given that people saw, and thought, that apples were red long before they even had the concept of electromagnetic radiation? — Michael

The meanings of words change. Before there was a scientific test for what we should call "red" it would have been more a community decision - to be 'red' was simply to be a member of that group of things decreed to be 'red', but nowadays, I suspect people will defer to the scientific measurement.

You "reaching" for the word "red" to describe apples isn't just something that happens in a vacuum. — Michael

I didn't say it happened in a vacuum. there are all sorts of other cognitive activities resultant from seeing an apple, but none of them have anything to do with 'red'. 'Red' is a word, so it is resultant of activity in my language centres.

And presumably you're not a p-zombie that just mindlessly responds to stimulation by spouting out words. — Michael

The concept of p-zombies makes no sense, so I can't answer this question. You might as well say "presumably you're not a robot with no Elan Vitale?". I don't consider it part of serious conversation to invoke made-up forces which are completely undetectable. -

Isaac

10.3kYou can build furniture out of the something in the world that has caused me to perceive a tree — RussellA

Isaac

10.3kYou can build furniture out of the something in the world that has caused me to perceive a tree — RussellA

What could we call that thing...? If only there was a word for the thing in the world which I can make furniture out of, climb, get fruit from, paint the image of, sit under the shade of....

.... We really need a word for thing.

I suggest "tree(a)", what with the word "tree" already having been taken and all. -

Michael

16.8kIt means that I'll reach for the word "red" if asked to describe the colour.

Michael

16.8kIt means that I'll reach for the word "red" if asked to describe the colour.

...

I didn't say it happened in a vacuum. there are all sorts of other cognitive activities resultant from seeing an apple, but none of them have anything to do with 'red'. 'Red' is a word, so it is resultant of activity in my language centres. — Isaac

People can see red even if they don't have a language to describe colour. They can feel pain even if they don't have a language to describe pain. They can smell roses even if they don't have a language to describe smells.

In fact smells are a good example this. I can smell so many different things and yet I don't have words to describe each kind of smell. There's no thinking involved in this. I don't think, "it's smell X" or "it's smell Y". I just smell.

The meanings of words change. Before there was a scientific test for what we should call "red" it would have been more a community decision - to be 'red' was simply to be a member of that group of things decreed to be 'red', but nowadays, I suspect people will defer to the scientific measurement. — Isaac

What a young child means when they say that an apple is red is exactly what I mean when I say that an apple is red, but I know about electromagnetic radiation and the young child doesn't. It just isn't the case that when I say "(I see that) the apple is red" that I am saying anything about quantum mechanics, and it's certainly not the case that when I see that the apple is red (but say nothing) that I am thinking anything about quantum mechanics. I'm just seeing. -

RussellA

2.7kIf this is true, it's not a discovery about seeing but only about the grammar of 'see.' — green flag

RussellA

2.7kIf this is true, it's not a discovery about seeing but only about the grammar of 'see.' — green flag

Yes, which shows the importance of Wittgenstein's discussion of the language game in Philosophical Investigations. -

Michael

16.8kIf this is true, it's not a discovery about seeing but only about the grammar of 'see.' — green flag

Michael

16.8kIf this is true, it's not a discovery about seeing but only about the grammar of 'see.' — green flag

Yes, that's where much of this discussion gets lost; in irrelevant arguments about grammar.

We use the word "see" in (at least) two slightly different ways, with direct and indirect realists having a preference for one or the other, and it distracts from the more pertinent epistemological problem of perception (the relationship between phenomenology and the mind-independent nature of things).

We can talk about the schizophrenic hearing voices (that aren't there), or we can talk about the schizophrenic not "actually" hearing voices (because there aren't any). The idea that one or the other is in some sense the "correct" way of talking, or says something about the philosophy or science of perception, is mistaken. They're just different ways of talking that have nothing to do with the actual disagreement between direct and indirect realists. -

RussellA

2.7kWhat could we call that thing...? If only there was a word for the thing in the world which I can make furniture out of, climb, get fruit from, paint the image of, sit under the shade of........ We really need a word for thing.......I suggest "tree(a)", what with the word "tree" already having been taken and all. — Isaac

RussellA

2.7kWhat could we call that thing...? If only there was a word for the thing in the world which I can make furniture out of, climb, get fruit from, paint the image of, sit under the shade of........ We really need a word for thing.......I suggest "tree(a)", what with the word "tree" already having been taken and all. — Isaac

This is the slightly mad bit.......That 'something that has caused me to perceive a "tree'?...........It's a tree........That's what a tree is. — Banno

Yes, "tree" is a good word. Within our language game we have the word "tree".

However, in the absence of any English speaker, the word "tree" would not exist, and "trees" would not exist in the world. In the absence of any English speakers, no one could discover in the world "trees". "Trees" only exist in the minds of speakers of the English language.

I perceive something that has been named "tree". As "trees" only exist in the mind, I am perceiving something in my mind that only exists in my mind, leading to a self-referential circularity.

This is the flaw in Searle's solution of the "intentionality of perception" to the epistemological problem of how we can gain knowledge of objects in the real world from private sense data, in that his solution leads to a similar self-referential circularity.

As an Indirect Realist I directly see a tree, I don't see a model of a tree. Searle wrote "The experience of pain does not have pain as an object because the experience of pain is identical with the pain". Similarly, the experience of seeing a tree does not have a tree as an object because the experience of seeing a tree is identical with the tree.

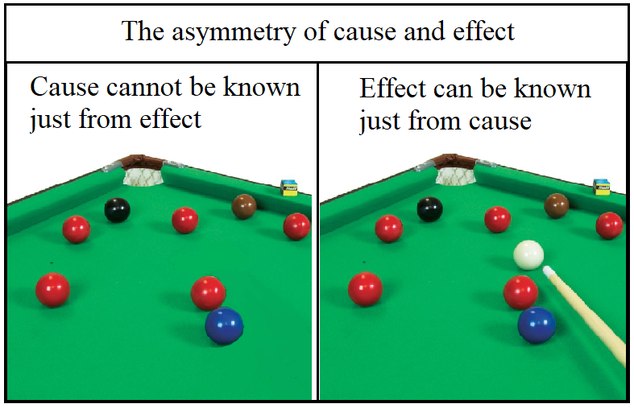

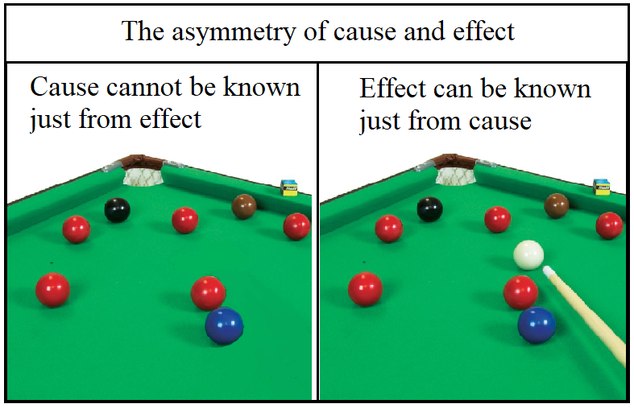

I have an innate belief in the law of causation, in that for every effect there is a cause, as well as the belief that the cause of an effect cannot be known just from knowing the effect. Combining these, my perceiving a "tree" must have been caused by something, yet I cannot know just from my perception what caused it.

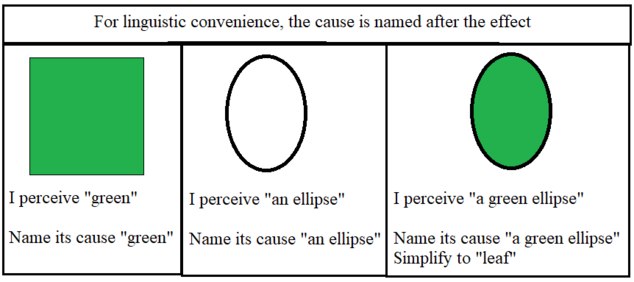

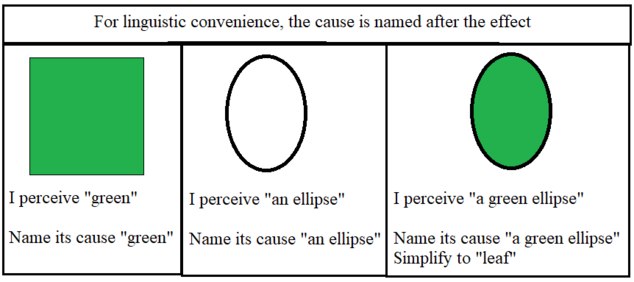

Yet I need a name for the cause of my perception of a tree. My solution is to give the cause the same name as the effect. Therefore, if I see the colour green, I name its cause green. If I hear a grating noise, I name its cause a grating noise. If I smell an acrid smell, I name its cause an acrid smell. If I feel something silky, I name its cause silky. If I taste something bitter, I name its cause bitter. If I perceive a tree, I name its cause a tree.

"Trees" only exist within the language game. "Trees" exist within the mind as not only the name for what is perceived by the mind but also as the name of the unknown cause of that perception, ie "a tree" is the cause of perceiving "a tree". -

Michael

16.8kHowever, in the absence of any English speaker, the word "tree" would not exist, and "trees" would not exist in the world. — RussellA

Michael

16.8kHowever, in the absence of any English speaker, the word "tree" would not exist, and "trees" would not exist in the world. — RussellA

Use-mention error.

In the absence of any English speaker the word "tree" wouldn't exist, but the object currently referred to by the word "tree" would exist.

Or, more simply, that thing over there is a tree, and that thing over there would continue to exist even if we stopped using the word "tree". It might no longer be called a tree, but it would still exist. And newly discovered animals don't come into existence only when we name them. They exist, and are what they are, even before we call them something.

There's a very peculiar obsession with language in this discussion. It's not clear to me what English grammar and vocabulary has to do with perception. Are people asserting a very extreme version of the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis? -

RussellA

2.7kIn the absence of any English speaker the word "tree" wouldn't exist, but the object currently referred to by the word "tree" would exist. — Michael

RussellA

2.7kIn the absence of any English speaker the word "tree" wouldn't exist, but the object currently referred to by the word "tree" would exist. — Michael

Exactly, that is what an Indirect Realist would say. The Direct Realist would have said "In the absence of any English speaker, the word "tree" wouldn't exist, but the tree would still exist in the world"

There's a very peculiar obsession with language in this discussion — Michael

As I believe in the ontology of Neutral Monism, where reality consists of elementary particles and elementary forces in space-time, the meaning of the word tree is fundamental to my philosophical understanding. -

Michael

16.8kExactly, that is what an Indirect Realist would say. — RussellA

Michael

16.8kExactly, that is what an Indirect Realist would say. — RussellA

There's no meaningful difference between these two phrases:

1. In the absence of any English speaker the word "tree" wouldn't exist, but the object currently referred to by the word "tree" would exist.

2. In the absence of any English speaker the word "tree" wouldn't exist, but the tree would exist.

The second, however, is a more natural way of talking, and so should be preferred.

You need to read up on the use-mention distinction.

As I believe in the ontology of Neutral Monism, where reality consists of elementary particles and elementary forces in space-time, the meaning of the word tree is fundamental to my philosophical understanding. — RussellA

The meaning of the word "tree" has nothing to do with perception. Seeing and hearing and feeling has nothing to do with language. Blind people aren't blind because they lack the right vocabulary; they're blind because their eyes don't work.

I don't know the name of this animal. I can still see it. It still exists. Whether or not I see it directly or indirectly is the topic of this discussion, and the answer to that depends on the nature of experience and its relation to external world objects, and that has nothing to do with how we talk. We can consider ourselves to be illiterate mutes just for the sake of argument. Presumably we'd still see things (and if we're considering sight specifically, throw in the assumption that we're deaf, too).

-

RussellA

2.7kThis is a misreading of the private language argument. — Banno

RussellA

2.7kThis is a misreading of the private language argument. — Banno

My proposal is that Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations does not support Direct Realism.

Direct Realism argues that we perceive objects in the world as they really are, immediately and directly.

If Direct Realism is true, one person's private experience of something in the world, such as a tree, will be the same as another person's private experience of the same tree, meaning that each person will know the other person's private experiences.

Wittgenstein argues that nobody can know another person's private experiences

In para 272 of PI, Wittgenstein writes that nobody can know another person's private experiences:

"The essential thing about private experience is really not that each person possesses his own exemplar, but that nobody knows whether other people also have this or something else. The assumption would thus be possible—though unverifiable—that one section of mankind had one sensation of red and another section another."

The Private language argument prevents talking about or discussing the pros and cons of Indirect and Direct Realism

There is an excellent and informative article in Wikipedia, the Private language argument that I always refer to.

The Wikipedia article Private language argument notes that the private language argument argues that a language understandable by only a single individual is incoherent, from which it follows that there is no language that can talk about or describe inner and private experiences.

1) The private language argument argues that a language understandable by only a single individual is incoherent,

2) If the idea of a private language is inconsistent, then a logical conclusion would be that all language serves a social function.

3) For example, if one cannot have a private language, it might not make any sense to talk of private experiences or of private mental states.

4) In order to count as a private language in Wittgenstein's sense, it must be in principle incapable of translation into an ordinary language – if for example it were to describe those inner experiences supposed to be inaccessible to others

Direct Realism is the position that our inner experience of an object in the world is direct and immediate. Indirect Realism is the position that we cannot know whether or not our inner experience of an object in the world is direct and immediate.

As Wittgenstein's private language argument argues that no language can talk about or describe inner and private experiences, it follows that the pros and cons of Indirect and Direct Realism is not something that can be talked about or described.

Summary

On the one hand, Wittgenstein's private language argument prevents discussion of Indirect and Direct Realism, but on the other hand, Wittgenstein writes that nobody can know another person's private experiences. That nobody can know another person's private experiences is at odds with the consequences of Direct Realism.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum