-

Moliere

6.5kHeh. That's not a thought I want to dissolve. I'm admitting it's the weak point in my thinking! :) -- it's something I see as a serious problem if I were to take my posited categories as the real. I'm making up another set of categories to offer to solve one set of problems, but admitting that these are provisional [EDIT:and] are for a particular line of thinking rather than universal.

Moliere

6.5kHeh. That's not a thought I want to dissolve. I'm admitting it's the weak point in my thinking! :) -- it's something I see as a serious problem if I were to take my posited categories as the real. I'm making up another set of categories to offer to solve one set of problems, but admitting that these are provisional [EDIT:and] are for a particular line of thinking rather than universal. -

Janus

17.9kDo you doubt that what appears real to us, what can appear real to us, is not (or at least not necessarily or not the whole of) what is real per se? — Janus

Janus

17.9kDo you doubt that what appears real to us, what can appear real to us, is not (or at least not necessarily or not the whole of) what is real per se? — Janus

Yes! — Moliere

So just to be clear you think that what appears real to us is (necessarily the whole of) what is real per se?

I'm not sure I agree that life is fundamentally a mystery. . . . mostly I'd prefer to say "absurd", but that's pretty close in functional terms, too. — Moliere

Yes, the idea that life is absurd, at least as Camus framed it, is that it cannot answer the questions most important to us, and I think in that sense it follows that life is a mystery. -

Moliere

6.5kSo just to be clear you think that what appears real to us is (necessarily the whole of) what is real per se? — Janus

Moliere

6.5kSo just to be clear you think that what appears real to us is (necessarily the whole of) what is real per se? — Janus

Hrm this is sounding similar to my discussion with @RussellA now...

I'm getting stuck on the parenthetical comment since you're wanting clarity -- can you put the question without parentheses?

Yes, the idea that life is absurd, at least as Camus framed it, is that it cannot answer the questions most important to us, and I think in that sense it follows that life is a mystery. — Janus

Sounds about right to me. "Mystery" invokes more than I like, so I like to say "absurd", but I admit functional equivalence. -

frank

18.9kHeh. That's not a thought I want to dissolve. I'm admitting it's the weak point in my thinking! :) -- it's something I see as a serious problem if I were to take my posited categories as the real. I'm making up another set of categories to offer to solve one set of problems, but admitting that these are provisional [EDIT:and] are for a particular line of thinking rather than universal. — Moliere

frank

18.9kHeh. That's not a thought I want to dissolve. I'm admitting it's the weak point in my thinking! :) -- it's something I see as a serious problem if I were to take my posited categories as the real. I'm making up another set of categories to offer to solve one set of problems, but admitting that these are provisional [EDIT:and] are for a particular line of thinking rather than universal. — Moliere

Gotcha. :smile: -

Janus

17.9kI'm getting stuck on the parenthetical comment since you're wanting clarity -- can you put the question without parentheses? — Moliere

Janus

17.9kI'm getting stuck on the parenthetical comment since you're wanting clarity -- can you put the question without parentheses? — Moliere

Do you think what is real to us is the whole of what is real?

Sounds about right to me. "Mystery" invokes more than I like, so I like to say "absurd", but I admit functional equivalence. — Moliere

Invokes or evokes? I'm guessing you think counting life as a mystery, as opposed to merely thinking it absurd, opens the door to mysticism and/or religion, and for that reason you don't favour the framing? -

Moliere

6.5kDo you think what is real to us is the whole of what is real? — Janus

Moliere

6.5kDo you think what is real to us is the whole of what is real? — Janus

Put like that -- I believe it to be the case, but I do not know it to be the case. And I suspect the whole is not knowable, so knowledge cannot settle whether there is more to the real than what is real to us.

So what does? That's something I still ask and wonder about.

Invokes or evokes? I'm guessing you think counting life as a mystery, as opposed to merely thinking it absurd, opens the door to mysticism and/or religion, and for that reason you don't favour the framing? — Janus

Yes.

Though I want to highlight that it's very much a for me thing. For me, since philosophy is at least fairly personal, it's just what it looks like to me if asked. I'm definitely skeptical of mysticism and religion, but in a way that's not meant to posit myself as somehow above it. I couldn't make a distinction between invokes/evokes logically, though my word choice indicates what I feel. -

Janus

17.9kPut like that -- I believe it to be the case, but I do not know it to be the case. And I suspect the whole is not knowable, so knowledge cannot settle whether there is more to the real than what is real to us.

Janus

17.9kPut like that -- I believe it to be the case, but I do not know it to be the case. And I suspect the whole is not knowable, so knowledge cannot settle whether there is more to the real than what is real to us.

So what does? That's something I still ask and wonder about. — Moliere

Saying the whole is not knowable seems to imply that there is that which is unknowable. If there were that which is unknowable, would it follow that it is real, or would you say the word "real" here would be misapplied?

I take it that when you you say "knowable" you mean 'discursively knowable' and then you go on to wonder if there could be another way to "settle it". Would settling it, for you, imply some kind of non-discursive knowing or just arriving at a feeling of its being settled? -

Moliere

6.5kSaying the whole is not knowable seems to imply that there is that which is unknowable. If there were that which is unknowable, would it follow that it is real, or would you say the word "real" here would be misapplied? — Janus

Moliere

6.5kSaying the whole is not knowable seems to imply that there is that which is unknowable. If there were that which is unknowable, would it follow that it is real, or would you say the word "real" here would be misapplied? — Janus

I agree with your deductions.

I think I'd have to remain agnostic there. I can't know if it's misapplied because it's not known. And I'm not sure how I get to that, now that I think on it -- I was clarifying and answering, not arguing.

I take it that when you you say "knowable" you mean 'discursively knowable' and then you go on to wonder if there could be another way to "settle it". Would settling it, for you, imply some kind of non-discursive knowing or just arriving at a feeling of its being settled? — Janus

In a way it would have to be a feeling that it's settled, but I'm not sure if that would be discursive or non-discursive. Gets back to the first question -- "the whole" is what I'm thinking, but I'm not sure how to get there since it wasn't in the categories posited so far. -

plaque flag

2.7kThat's a great phrase which highlights why I didn't feel comfortable with the original distinction between Semantic/Phenomenological direct realism. — Moliere

plaque flag

2.7kThat's a great phrase which highlights why I didn't feel comfortable with the original distinction between Semantic/Phenomenological direct realism. — Moliere

Not sure exactly what you mean. In case it helps, for me the lifeworld has birds and blunders that we can talk about. Such articulated entities are just there for us. A (mistaken or less advisable) deworlding approach plucks all the leaves away to find the real artichoke. We acted as though we had tried to find the real artichoke by stripping it of its leaves. -

Janus

17.9kI think I'd have to remain agnostic there. I can't know if it's misapplied because it's not known. And I'm not sure how I get to that, now that I think on it -- I was clarifying and answering, not arguing. — Moliere

Janus

17.9kI think I'd have to remain agnostic there. I can't know if it's misapplied because it's not known. And I'm not sure how I get to that, now that I think on it -- I was clarifying and answering, not arguing. — Moliere

Yes, it's an odd situation. If we want to say there is something unknowable we seem to be commit to saying it is real, and yet the term 'real' finds its genesis in the empirical context, where it is (at least in part) inter-subjective agreement that establishes what falls into the category 'real' and what into the category 'imaginary'. Numbers seem to be an edge case insofar as they cannot (cannot all at least) be classed as imaginary, and even the ones that are so classed have real applications.

Additionally there would seem to be no way to decide if the term real is misapplied if understood to be extended beyond the ambit of human experience. Of course there are those who, in a positivistic spirit, will dogmatically claim that the term is certainly misapplied in that extra-empirical scenario, asserting without substantive argument that we don't know what we are talking about when we apply it this way.

In a way it would have to be a feeling that it's settled, but I'm not sure if that would be discursive or non-discursive. Gets back to the first question -- "the whole" is what I'm thinking, but I'm not sure how to get there since it wasn't in the categories posited so far. — Moliere

We have an idea of the whole, but it cannot be an item of perceptual experience (and this goes for all wholes including whole objects) which begs the question as to whether the idea is a kind of mirage or whether the human intelligence is capable of intuitions which are not founded on the senses. But then how could we ever decide about that? -

RussellA

2.6kThere is debate among modern interpreters over whether Kant is an indirect realist — Jamal

RussellA

2.6kThere is debate among modern interpreters over whether Kant is an indirect realist — Jamal

Philosophers have made good livings from arguing as to what Kant meant. Early twentieth-century philosophers of perception presented their direct realist views of perceptual experience in anti-Kantian terms. Today, some philosophers attempt to place Direct Realism within a Kantian framework by arguing that Kant can be read as a conceptualist rather than non-conceptualist.

Perhaps the debate comes down to the two varieties of Direct Realism, the early 20th C Phenomenological Direct Realism and the contemporary Semantic Direct Realism. Phenomenological Direct Realism (PDR) may be described as a direct perception and direct cognition of the object "tree" as it really is in a mind-independent world. Semantic Direct Realism (SDR) may be described as an indirect perception but direct cognition of the object "tree" as it really is in a mind-independent world.

He explicitly states that we perceive the external world "immediately," and what he calls representations constitute the perception and determination of objects, rather than standing in for them as images or constructions. We have awareness of objects not through anything like an inference from or construction of an internal image, but through an act of synthesis that puts the objects directly before us. — Jamal

Both the Indirect Realist and Direct Realist would agree that we perceive the world "immediately".

As Searle wrote: The relation of perception to the experience is one of identity. It is like the pain and the experience of pain. The experience of pain does not have pain as an object because the experience of pain is identical with the pain. Similarly, if the experience of perceiving is an object of perceiving, then it becomes identical with the perceiving. Just as the pain is identical with the experience of pain, so the visual experience is identical with the experience of seeing.

As an Indirect Realist, I feel pain, I don't feel the representation of pain. Similarly, when I see a tree, I directly see the tree, I don't see the representation of a tree.

The Indirect Realist differs to the Direct Realist. The Indirect Realist argues that the tree I see exists only this side of the senses, whereas the Direct Realist would argue that there is also an identical tree the other side of my senses.

Both the Indirect and Direct Realist perceive the world "immediately", though they differ as to where exactly this world is.

And yes, he does use "realism" to refer to claims that we can know things in themselves — Jamal

I assume we both agree that Kant was not an Berkelean Idealist, where physical objects are constructions of the mind. Kant's transcendental idealism may be described as, on the one hand as a rejection of Berkelean idealism, and on the other hand that the things we perceive exist independently of us and about which we cannot directly cognize, yet grounds the way they appear to us.

In other words, for Kant, "Existence", in that there are things-in-themselves, "Humility", in that we know nothing of things-in-themselves and "Affectation", in that things -in-themselves causally affect us.

For Kant, the noumenal realm is not reality, since it is merely a product of reason. Rather, reality is that which we know about through experience and science. The clue to this is that reality for Kant is one of the categories of the understanding, thus it can only apply to phenomena. — Jamal

You are making the case for Indirect Realism.

For the Direct Realist, perceptual reality is the noumenal world, the other side of our senses, where there are things in a world outside our mind that are perceived immediately or directly rather than inferred on the basis of perceptual evidence.

For the Indirect Realist, perceptual reality is the phenomenal world, this side of our senses, where things outside our mind are perceived indirectly and inferred on the basis of perceptual evidence.

In summary, for both Kant and the Indirect Realist, perceptual reality is the phenomenal world this side of the senses whereas for the Direct Realist perceptual reality is the noumenal world , the other side of our senses. -

RussellA

2.6kPerhaps you can find those that call themselves 'direct realists' that do this, but to me this is the wrong way to go and misses what's good in 'my' take on direct realism. — plaque flag

RussellA

2.6kPerhaps you can find those that call themselves 'direct realists' that do this, but to me this is the wrong way to go and misses what's good in 'my' take on direct realism. — plaque flag

What's your take on Direct Realism ? -

frank

18.9kPerhaps you can find those that call themselves 'direct realists' that do this, but to me this is the wrong way to go and misses what's good in 'my' take on direct realism.

frank

18.9kPerhaps you can find those that call themselves 'direct realists' that do this, but to me this is the wrong way to go and misses what's good in 'my' take on direct realism.

— plaque flag

What's your take on Direct Realism ? — RussellA

I was thinking about this while making coffee this morning. The OP touches on something that comes down to who you are rather than empirical or logical foundations.

This is why a scientific approach, or even adhering to standard viewpoints from philosophy of mind (like multiple realizability issues) are ignored in favor of presenting hypotheses.

As if the question in the OP was really: Could Direct Realism be Conceived in Such a Way that it Works? It's speculative philosophy driven by identity. I am this, so that needs to work. -

RussellA

2.6kHere's Hegel.

RussellA

2.6kHere's Hegel.

For if knowledge is the instrument by which to get possession of absolute Reality, the suggestion immediately occurs that the application of an instrument to anything does not leave it as it is for itself, but rather entails in the process, and has in view, a moulding and alteration of it.

Or, again, if knowledge is not an instrument which we actively employ, but a kind of passive medium through which the light of the truth reaches us, then here, too, we do not receive it as it is in itself, but as it is through and in this medium. — plaque flag

Hegel sets out the Indirect Realist's problem with bridging the gap between our conscious mind on the one side and a mind-independent world on the other, between knowledge and the Absolute.

Whether knowledge is an instrument or passive medium to bridge the gap, it alters what passes from a mind-independent world to our conscious mind, meaning that our perceptions are indirect.. -

Moliere

6.5kNot sure exactly what you mean. In case it helps, for me the lifeworld has birds and blunders that we can talk about. Such articulated entities are just there for us. A (mistaken or less advisable) deworlding approach plucks all the leaves away to find the real artichoke. We acted as though we had tried to find the real artichoke by stripping it of its leaves. — plaque flag

Moliere

6.5kNot sure exactly what you mean. In case it helps, for me the lifeworld has birds and blunders that we can talk about. Such articulated entities are just there for us. A (mistaken or less advisable) deworlding approach plucks all the leaves away to find the real artichoke. We acted as though we had tried to find the real artichoke by stripping it of its leaves. — plaque flag

Language-as-organ puts it in a similar category to eyes-as-organ -- both organs of perception which compose a body. So rather than semantics as something which is distinct from our perceptions it puts them together in a phrase. -

frank

18.9k

frank

18.9k

For the most part language is a collection of abstract objects. The bodily part is utterances (sounds and marks, reading and listening). But words and sentences are something else. The fact that the same sentence can be expressed by multiple utterances (a text engraved in stone vs a professor's quotation,) shows this.

I'm just saying that if your goal was to stick to a materialist base, using language as an organ won't work. You'll have to adopt a behaviorist, inscrutable reference, sort of outlook. -

Moliere

6.5kSomething I cannot decide, not even with an aesthetic guess, whether it is or is not mind-independent is individuation. It's a phenomena which is understandable within both language and perception: Names-predicates, in the first case, and object-foreground in the latter. And it's understandable as a real phenomena, similar to the way I was talking about causation earlier -- perhaps we trip across individuation because it's a real phenomena rather than because it's our way of dividing up the world. How could you possibly tell the difference?

Moliere

6.5kSomething I cannot decide, not even with an aesthetic guess, whether it is or is not mind-independent is individuation. It's a phenomena which is understandable within both language and perception: Names-predicates, in the first case, and object-foreground in the latter. And it's understandable as a real phenomena, similar to the way I was talking about causation earlier -- perhaps we trip across individuation because it's a real phenomena rather than because it's our way of dividing up the world. How could you possibly tell the difference? -

plaque flag

2.7kWhether knowledge is an instrument or passive medium to bridge the gap, it alters what passes from a mind-independent world to our conscious mind, meaning that our perceptions are indirect.. — RussellA

plaque flag

2.7kWhether knowledge is an instrument or passive medium to bridge the gap, it alters what passes from a mind-independent world to our conscious mind, meaning that our perceptions are indirect.. — RussellA

This assumption of the instrument/medium is what's being mocked as a fear of truth that confuses itself for a fear of error.

With suchlike useless ideas and expressions about knowledge, as an instrument to take hold of the Absolute, or as a medium through which we have a glimpse of truth, and so on ..., we need not concern ourselves. Nor need we trouble about the evasive pretexts which create the incapacity of science out of the presupposition of such relations, in order at once to be rid of the toil of science, and to assume the air of serious and zealous effort about it. -

plaque flag

2.7kThe relation of perception to the experience is one of identity. It is like the pain and the experience of pain. The experience of pain does not have pain as an object because the experience of pain is identical with the pain. Similarly, if the experience of perceiving is an object of perceiving, then it becomes identical with the perceiving. Just as the pain is identical with the experience of pain, so the visual experience is identical with the experience of seeing. — RussellA

plaque flag

2.7kThe relation of perception to the experience is one of identity. It is like the pain and the experience of pain. The experience of pain does not have pain as an object because the experience of pain is identical with the pain. Similarly, if the experience of perceiving is an object of perceiving, then it becomes identical with the perceiving. Just as the pain is identical with the experience of pain, so the visual experience is identical with the experience of seeing. — RussellA

He articulates quite well a default assumption. He makes a certain (questionable) conceptual norms explicit. But what he presents is no discovery. He did not check and see, dipping a ladle into the. bucket of his 'Private Experience.' Ladies and gentlemen, I give you an 'impossible' blend of scientism and mysticism... -

plaque flag

2.7kWhat's your take on Direct Realism ? — RussellA

plaque flag

2.7kWhat's your take on Direct Realism ? — RussellA

We talk about the world (directly) in our language according to our rational and semantic norms. How dare I make such a claim ? Simple. A philosopher (in that role) can't deny it. He'd be talking about our world or just babbling. He'd be talking in our language <semantic norms> or I can't understand you pal. He'd be appealing to our (self-transcending, my self and yours) rational norms or just blabbing about his hunch or prejudice. So pineal gremlins know not what they say when they claim that I can't know that I'm not a pineal gremlin. They have smuggled in norms from the outside without realizing it.

We are not ghosts trapped behind Images that may or may not mediate a Hidden world beyond them (gremlins in the pineal gland). We are not those Images themselves (metaphysical subjects, more plausible at first than the pineal gremlin.) I capitalize to stress how adjacent philosopher's Entities are to Mysticism. Our anemic mythos* is one step away from Inner Light. I'm not even against mysticism, but let's not mix oil and water and confuse ourselves.

Selves and a meaningful language and others all in one and the same worldareis an unbreakable unity which 'must' and always in fact is 'assumed' when one tries to do philosophy. [ <being-in-the-world-in-language-and-norms-with-others> ] So much of this framework is so stubbornly and deeply tacit that folks lean on it unwittingly, just as they do the metaphorics of beetles in boxes.

*See Derrida and Anatole France on 'white mythology' for more detail on the unshakeable metaphorical origins (can't wipe all that mud of their feet) of our technical abstractions. Or check Metaphors We Live By (Lakoff). -

RussellA

2.6kThis assumption of the instrument/medium is what's being mocked as a fear of truth that confuses itself for a fear of error.

RussellA

2.6kThis assumption of the instrument/medium is what's being mocked as a fear of truth that confuses itself for a fear of error.

With suchlike useless ideas and expressions about knowledge, as an instrument to take hold of the Absolute, or as a medium through which we have a glimpse of truth, and so on ..., we need not concern ourselves. — plaque flag

Considering that we only get our knowledge about the external world through our senses, it seems very cavalier for Hegel to write that we need not concern ourselves about the role our senses play in understanding the external world.

But what he presents is no discovery. — plaque flag

I agree. As an Indirect Realist I agree with Searle that the experience of pain does not have pain as an object because the experience of pain is identical with the pain.

Unfortunately, many who argue against Indirect Realism don't accept this. They believe that Indirect Realism requires that there must be something in the brain that is interpreting incoming data, something they often call a homunculus.

We talk about the world (directly) in our language according to our rational and semantic norms...A philosopher (in that role) can't deny it. He'd be talking about our world or just babbling. — plaque flag

I agree that we rationally and directly talk about the world.

The question is, where is this "world". Wittgenstein, for example, in Tractatus avoided this question.

The Indirect Realist would agree that this "world" exists in language. But this doesn't distinguish the Indirect Realist from the Direct Realist.

What else distinguishes the Direct Realist from the Indirect Realist ? -

plaque flag

2.7kConsidering that we only get our knowledge about the external world through our senses, it seems very cavalier for Hegel to write that we need not concern ourselves about the role our senses play in understanding the external world. — RussellA

plaque flag

2.7kConsidering that we only get our knowledge about the external world through our senses, it seems very cavalier for Hegel to write that we need not concern ourselves about the role our senses play in understanding the external world. — RussellA

Hegel is not denying the use of our sense organs. As I see it, you are locked in a particular metaphor so that you can't yet make sense of alternative conceptualizations without this metaphor.

We need sense organs, yes, but we aren't gremlins trapped in pineal glands. We aren't even our brains. We who do philosophy and science together are enmeshed and even products of semantic-rational norms. I claim that it's this normative linguistic center of rationality that makes indirect realism absurd.

I agree. As an Indirect Realist I agree with Searle that the experience of pain does not have pain as an object because the experience of pain is identical with the pain.

Unfortunately, many who argue against Indirect Realism don't accept this. They believe that Indirect Realism requires that there must be something in the brain that is interpreting incoming data, something they often call a homunculus. — RussellA

Recently I've criticized both versions. In one version, there's a pineal gremlin looking at the screen. In the other version the gremlin is the screen. The self 'is' sensations and ideas. But, while this is better, it entirely misses the normative function of the self. It fails to explain the unity of the reasoning voice, that these sensations and ideas cohere, have structure and direction, are stretched between the past and the future with memory and anticipation.

I agree that we rationally and directly talk about the world. — RussellA

:up:

The question is, where is this "world". — RussellA

It's all around us. It's the world. It's the one philosophers talk about and make claims about. Even people who want to talk about their private images of world are still talking as if those images were also 'in' the world, even if invisible to all others.

Even if just as an experiment, start with what philosophy thinks it is doing and work backwards. What must be true (what must we assume) for the 'game' of philosophy to make sense ? We have to be talking rationally in a shared language about a shared world. To talk rationally is to tell a story that does not contradict itself. Look for what a self is there, as a storyteller who is not allowed to disagree with itself. Look at what we are doing now, keeping track of what we and the other has said, both of us appealing to reason, careful to make only legitimate inferences. As Hegel might put, there is a we at the foundation of the I, even if it's 'just' cultural software. And what do I do but argue for the adoption of new inferential norms --- try to convince you that Q legitimately follows from P, or that conceiving the self in way X leads to contradiction. In other worlds, selves are coherent inferential social avatars ---or something like that.... -

plaque flag

2.7kWhat else distinguishes the Direct Realist from the Indirect Realist ? — RussellA

plaque flag

2.7kWhat else distinguishes the Direct Realist from the Indirect Realist ? — RussellA

The indirect realist (as I understand it) posits a internal image which simply is what it is, glowingly present, and may or may not represent accurately what's going on the external world.

The direct realist tries to do without this internal image, but not without sense organs. The direct realist is not so much focused on how the eyes see the tree and not the image of the tree, even if they will put the event this way. What really matters are linguistic norms. The 'I' that sees the tree exists within the space of reasons. The 'I' is like a character on a stage among others egos. Direct realists aren't worried about the internal structure of this 'I.' That's not the point. Language is fundamentally social, world-directed, and self-transcending. To see the tree is more usefully understand as to claim 'I see a tree.' We now think of this claim as a move in a social game. Think of a witness at a trial who had better keep his story straight. In social space, this witness 'is' his story or a kind of organizing avatar held responsible for it. Maybe this isn't all that a self is, but it's the way selves are 'used' in philosophy, so it's weird that it's mostly ignored. Why didn't Descartes ask about where logic itself came from ? As the proper (normative) way to think ? How did he know he was a self ? Why not random words attributed to no one rattling away in his skull? But instead we find something curious and reasonable already in place and knowing a language or two ....He 'was' that language (he was right in an important way), but language is anti-private, anti-isolated...it's bundled with a we. -

frank

18.9kThe 'I' that sees the tree exists within the space of reasons. — plaque flag

frank

18.9kThe 'I' that sees the tree exists within the space of reasons. — plaque flag

Apparently, so is the tree. The epiphany comes from looking at the tree the way an artist would. Just see the shapes and shades. When you realize that "tree" is an idea that organizes the data in the visual field in certain way, you begin to see that it's all ideas out there, this contrasted with that, foreground against background.

This isn't opposed to realism, it's just a particular way of understanding what it is that we call reality. It's a kind of projection, although that isn't right either. That's just a way of putting it phenomenologically.

BTW, I like talking to you because you're so poetic, it invites the same. Somethings come out better as poetry than as a recipe. See? More poetry. -

RussellA

2.6kIt's all around us. It's the world. It's the one philosophers talk about and make claims about.......................We have to be talking rationally in a shared language about a shared world. — plaque flag

RussellA

2.6kIt's all around us. It's the world. It's the one philosophers talk about and make claims about.......................We have to be talking rationally in a shared language about a shared world. — plaque flag

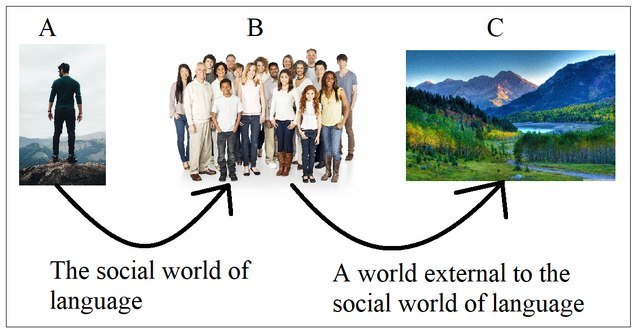

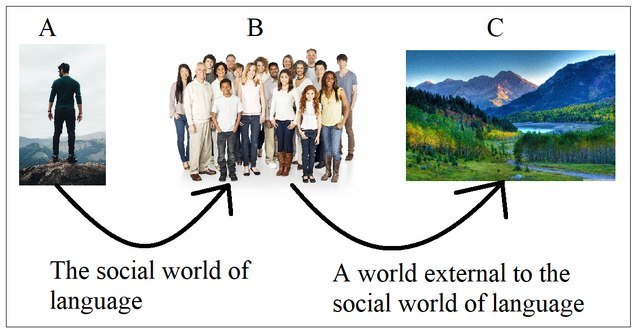

Your posts are about the relationship between the individual and a social world of which they are a part, of which language is critical.

Both the Indirect and Direct Realist would agree about the importance of language.

The problem is, however, the relationship between the social group and the world external to the social group, and whether the social group have indirect or direct knowledge of this external world.

The Direct Realist would say that the tree exists in a mind-independent world exactly as we perceive the tree to be in our minds. The Indirect Realist would disagree. -

Michael

16.8kWhat really matters are linguistic norms. — plaque flag

Michael

16.8kWhat really matters are linguistic norms. — plaque flag

That doesn't seem accurate. The epistemological problem of perception concerns the extent to which perception informs us about what the world is like. That doesn't seem to have anything to do with language at all.

Direct realists argued that we can trust that perception informs us about what the world is like because the world and its nature presents itself in experience. Indirect realists argued that we can't trust that perception informs us about what the world is like because experience is, at best, representative of the world and its nature. -

plaque flag

2.7kBut words and sentences are something else. The fact that the same sentence can be expressed by multiple utterances (a text engraved in stone vs a professor's quotation,) shows this. — frank

plaque flag

2.7kBut words and sentences are something else. The fact that the same sentence can be expressed by multiple utterances (a text engraved in stone vs a professor's quotation,) shows this. — frank

Have you considered equivalence classes ? You seem to be using the container metaphor. Different wrappers can contain the same candy. We can also think of different expressions having the roughly the same use. For this reason they have the same [enough] meaning / use. -

plaque flag

2.7kWhat really matters are linguistic norms. — plaque flag

plaque flag

2.7kWhat really matters are linguistic norms. — plaque flag

That doesn't seem accurate. — Michael

Why should I be accurate, seriously ? (I'm not being rude or irrationalist here but trying to make explicit what we are doing at this very moment.)

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum