-

Wayfarer

26.2kThe important aspects of life are precisely those which cannot be publicly demonstrated. — Janus

Wayfarer

26.2kThe important aspects of life are precisely those which cannot be publicly demonstrated. — Janus

But can they be subject to philosophical discourse? The whole point of the remainder of your post is to uphold a taboo - these things ought not to be discussed, they're subjective, they're transient and basically inconsequential. Hadot himself doesn't say that. He says that philosophy as understood in the contemporary academy has lost sight of its original motivation, to its detriment. By writing his books, he was seeking to re-instate that original purpose. Not declare it out-of-bounds.

I read a little of Kierkegaard's 'Concluding Non-Scientific Postscript' recently. A major thrust of that book is that philosophical insight does have an intrinsically subjective nature, but that doesn't imply that this is not something that can be understood or conveyed. Rather, that it can't be reduced to the procrustean bed of the objective sciences. -

Janus

18kBut can they be subject to philosophical discourse? The whole point of the remainder of your post is to uphold a taboo - these things ought not to be discussed, they're subjective, they're transient and basically inconsequential. Hadot himself doesn't say that. He says that philosophy as understood in the contemporary academy has lost sight of its original motivation, to its detriment. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kBut can they be subject to philosophical discourse? The whole point of the remainder of your post is to uphold a taboo - these things ought not to be discussed, they're subjective, they're transient and basically inconsequential. Hadot himself doesn't say that. He says that philosophy as understood in the contemporary academy has lost sight of its original motivation, to its detriment. — Wayfarer

We can talk about the practices themselves, but ideas like Karma, God, the afterlife and so on are too nebulous and underdetermined to be able to form subjects for philosophical discourse, in the form of arguments at least, in my view. I'd say the same about aesthetics and metaphysics. I mean, there's nothing wrong with speculating; the problems come when people think the purported truths of such speculations are in any way rationally (not to mention empirically) demonstrable.

I see such speculations as good and potentially enriching exercises of the imagination; arguing about them; like arguing about poetry is a waste of time. For example, you might think T S Eliot is great, and I might think he is mediocre; or Osho was a sage and Sri Aurobindo was deluded or a charlatan, there is no point arguing about it; so, I don't think such things have a significant place in philosophy; philosophy considered as argumentation, at least.

Hadot's point, as I understand it, is that the older kind of philosophy, which was not about argumentation and asserting anything, has been lost. I don't know if that's true; there may be practicing Stoics, Neoplatonists and Epicureans for all I know. To repeat, the point of such philosophies is about practice and not about proving any metaphysical theory. I'm not saying they have no value; obviously they have value to those who want to practice them. -

Wayfarer

26.2kIf we pressure people to stop talking about gold because of the danger of fool's gold, then we deprive many people of the search and possession of real gold. — Leontiskos

Wayfarer

26.2kIf we pressure people to stop talking about gold because of the danger of fool's gold, then we deprive many people of the search and possession of real gold. — Leontiskos

I see what you mean. -

Tom Storm

10.9kIn more general terms, how severing reason from the good is nihilism can be seen in the ideal of objectivity and the sequestering of "value judgments". Political philosophy, for example, is shunned in favor of political science.

Tom Storm

10.9kIn more general terms, how severing reason from the good is nihilism can be seen in the ideal of objectivity and the sequestering of "value judgments". Political philosophy, for example, is shunned in favor of political science.

— Fooloso4

I think this is more or less correct. :up: — Leontiskos

Can you say some more about why? -

wonderer1

2.4k'Physical' meaning what, exactly? — Wayfarer

wonderer1

2.4k'Physical' meaning what, exactly? — Wayfarer

What do you mean by 'exactly'? I've grown to think more and more like Feynman:

“You see, one thing is, I can live with doubt and uncertainty and not knowing. I think it's much more interesting to live not knowing than to have answers which might be wrong. I have approximate answers and possible beliefs and different degrees of certainty about different things, but I'm not absolutely sure of anything and there are many things I don't know anything about, such as whether it means anything to ask why we're here, and what the question might mean. I might think about it a little bit and if I can't figure it out, then I go on to something else, but I don't have to know an answer, I don't feel frightened by not knowing things, by being lost in a mysterious universe without having any purpose, which is the way it really is so far as I can tell. It doesn't frighten me.”

― Richard P. Feynman

I think you most likely have an intuitive sense of what people mean by physical, and you'll just have to work with your intuition, because I can't give you mine. I also think you know enough about physics to know that any exact claim would be unjustifiable.

I can encode information - a recipe, a formula, a set of instructions - in all manner of physical forms, even in different media, binary, analog, engraved on brass. In each case, the physical medium and the symbolic form may be completely different, while the information content remains the same. — Wayfarer

Right. You have a variety of ways of interpreting things, which can be applied to a variety of ways information can be encoded in the structure of physical stuff. That's one of the more interesting things about homo sapien brains.

So how can the information be physical? — Wayfarer

By being encoded in the structure of physical stuff.

Why think there is information available to us, other than that which can come to us via configurations of physical stuff?

I don't think that, "Because once upon a time someone said he had it all figured out, and other people believed him.", amounts to a good reason.

What's encoded in configurations of physical reality is that we are all social primates here. As Plantinga points out (though I think more unintentionally than intentionally) the likelihood - that there is good reason to question the reliability of our cognitive faculties - is high. Just look at the Israel thread to see how often people jump to wrong conclusions. -

Leontiskos

5.6kYes, I agree with that. The important aspects of life are precisely those which cannot be publicly demonstrated. The aesthetic dimension in architecture music, literature and the arts is of more value, or at least consists in a different kind of value, even though aesthetic quality, like any form of "direct knowing" cannot be rationally demonstrated or couched in propositional terms. — Janus

Leontiskos

5.6kYes, I agree with that. The important aspects of life are precisely those which cannot be publicly demonstrated. The aesthetic dimension in architecture music, literature and the arts is of more value, or at least consists in a different kind of value, even though aesthetic quality, like any form of "direct knowing" cannot be rationally demonstrated or couched in propositional terms. — Janus

Right.

I think it also needs to be acknowledged that if such transformations are ever achieved it is exceedingly rare, and mostly (perhaps always) transient, and given that those most likely to achieve such altered states are renunciates, I think it has little practical significance for general human life apart from possibly being a relatively minor (compared to the arts and popular religion) enriching aspect of culture. — Janus

Okay, interesting. This is a fairly large topic. We could phrase it as, "Are deep transformations accessible to the laity?" I don't want to get into that here.

Altered states of consciousness are to be realized not by argument and critique but by praxis. — Janus

I tend to think there is a complex interrelation between ideation and experience.

To repeat, the point of such philosophies is about practice and not about proving any metaphysical theory. — Janus

Like , I do not read Hadot this way. I think Hadot sees discourse and practice as two poles that mutually influence one another, and he critiques the undue emphasis on discourse in modern philosophy, but I don't see him claiming that practice subsumes or displaces discourse. Or in other words, forms of philosophical practice are in some ways as vulnerable to argumentation as philosophical discourse is. The renewed emphasis on practice creates a more holistic philosophical environment; but it doesn't make argument futile. -

Wayfarer

26.2kWhat do you mean by 'exactly'? — wonderer1

Wayfarer

26.2kWhat do you mean by 'exactly'? — wonderer1

As you've made a claim that 'Meaning depends on a physical interpretive context' so I'm asking, what do you mean by that? If it's a 'vague notion' then presumably it doesn't mean anything in particular.

So how can the information be physical?

— Wayfarer

By being encoded in the structure of physical stuff.

Why think there is information available to us, other than that which can come to us via configurations of physical stuff? — wonderer1

But how does it come to be so encoded, what is it that does the encoding and what interprets the code? I think you will find that they are very big questions, so I'm not trying to elicit an answer - like Feynmann says! - so much as a recognition that the answer is not obvious, and also not something that can be understood in terms of physics. As far as I can discern, the only instances of codes are the biological code - DNA - and in languages. In other words, part of the attributes of life and mind, and also part of what makes living things and minds not reducible to physical laws. -

Leontiskos

5.6kCan you say some more about why? — Tom Storm

Leontiskos

5.6kCan you say some more about why? — Tom Storm

I don't know if I can... The separation of reason from the good is something like the snuffing out of practical motive. It leads to the idea that, ultimately, there is no reason to do anything. There are only hypothetical imperatives. We could argue about whether that results in nihilism per se, but in any case it seems to come very close.

But this idea must first be understood:

Basic to the philosophy of Plato and Aristotle is the desire for and pursuit of the good. This must be understood at the most ordinary level, not as a theory but simply as what we want both for ourselves and those we care about. It is not only basic to their philosophy but basic to their understanding of who we are as human beings. — Fooloso4

Once that is understood then it becomes clear why separating reason from the good entails that there is no ultimate reason to do anything at all. "The good" is the psychological motive force for human beings, if you will (but not only that).

But by this account then quite a range of people who believe in transcendent entities, such as gods, might qualify as nihilists - [those who] do not have any conception of the good but only a divine command theory — Tom Storm

Divine command theory has a conception of the good. It conceives of the good as that which is divinely commanded. -

Leontiskos

5.6kTrue, but I think there is also an inverse correlation between public demonstrability and intrinsic value. That which must be publicly demonstrable tends toward utility, as a means rather than an end. — Leontiskos

Leontiskos

5.6kTrue, but I think there is also an inverse correlation between public demonstrability and intrinsic value. That which must be publicly demonstrable tends toward utility, as a means rather than an end. — Leontiskos

As Hadot says in Philosophy as a Way of Life, the ideas in those kinds of ancient philosophies were not to be critiqued or discussed... — Janus

It seems crucial to assert that the intrinsically valuable (ends in themselves) are a proper subject of argument. I think that is where we disagree. I think we must argue about the highest things.

So take for example the end of appreciating music. I think we can speak about this end, argue about it, learn about it, teach it, seek it, honor it, etc. Once we understand this end we can then speak/argue/learn/teach/seek/honor the proper means, such as technical proficiency, discernment of quality, etc. Nevertheless, the act of music appreciation is not publicly demonstrable in any obvious way, largely because appreciation is not the sort of thing done for the sake of demonstration. It would be incongruous to try to demonstrate appreciation (because demonstration pertains to means and appreciation pertains to ends).

So at the end of the day you seem to subscribe to the idea that we can argue and discourse about means, but not ends. That is a very common modern approach, but it is also precisely the point of disagreement.

(This also relates to Hadot's project in different ways.) -

Tom Storm

10.9kIt leads to the idea that, ultimately, there is no reason to do anything. There are only hypothetical imperatives. We could argue about whether that results in nihilism per se, but in any case it seems to come very close. — Leontiskos

Tom Storm

10.9kIt leads to the idea that, ultimately, there is no reason to do anything. There are only hypothetical imperatives. We could argue about whether that results in nihilism per se, but in any case it seems to come very close. — Leontiskos

I can kind of see that, but I would be one to argue about it. I guess it all depends upon how we understand nihilism and whether it comes in various degrees.

Once that is understood then it becomes clear why separating reason from the good entails that there is no ultimate reason to do anything at all. "The good" is the psychological motive force for human beings, if you will (but not only that). — Leontiskos

I guess in your "not only that" space you might come at this from a more platonic perspective? For me The Good is an artifact of human experience and reasoning and can only be contingent, even if there are large intersubjective communities of agreement. The experience of being human doesn't differ all that much in terms of most people wanting to flourish and avoid suffering.

Divine command theory has a conception of the good. It conceives of the good as that which is divinely commanded. — Leontiskos

I guess it does. But from my perspective this isn't actively engaged with the good as such and is merely following orders. But then my take on Yahweh/Allah is that he is an evil monster. So while a presuppositionalist Christian or Muslim theologian might hold that goodness emanates directly from the nature of god (thereby perhaps avoiding the Euthyphro dilemma), I would say this god, by Biblical accounts is a genocidal anathema.

But perhaps I am unfairly cobbling together philosophical points with specific literalist interpretations, so there's that... -

wonderer1

2.4kDivine command theory has a conception of the good. It conceives of the good as that which is divinely commanded. — Leontiskos

wonderer1

2.4kDivine command theory has a conception of the good. It conceives of the good as that which is divinely commanded. — Leontiskos

It's also associated with claims of horrendous things being divinely commanded. -

Leontiskos

5.6kI guess it does. But from my perspective this isn't actively engaged with the good as such and is merely following orders. — Tom Storm

Leontiskos

5.6kI guess it does. But from my perspective this isn't actively engaged with the good as such and is merely following orders. — Tom Storm

Yes, but this is an argument about what is good, and presupposes a desire for the good in both parties. You are saying to the divine command theorist, "You see divine commands as good, but they are not truly good. This other thing is truly good, and it is this that you ought to seek instead." Now if the divine command theorist had truly separated reason from the good then you would not be able to reason with them about what is good. You are right that the divine command theorist will reject a certain form of reasoning, but nevertheless they will not reject reasoning per se. They are liable to try to convince others that divine command theory is correct, and that divine commands are good (i.e. worthy of observance and honor).

(I will respond to the rest later.) -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kConsequently, I have wondered if we could take Nothingness seriously, and eliminate the perceived necessity for a mysterious ethereal substance. Take a typical atom for example, and watch as an electron (point particle) jumps up, and then back down, between energy levels (orbits). This up & down -- maximum to minimum -- action produces waveforms on an oscilloscope. But the actual jumps seem to occur almost instantaneously. So, what if we imagine them as quantum leaps without passing through the space (nothingness) in between. In that case, the pattern would look more like a series of dots than a sine wave curve. {see image below} — Gnomon

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kConsequently, I have wondered if we could take Nothingness seriously, and eliminate the perceived necessity for a mysterious ethereal substance. Take a typical atom for example, and watch as an electron (point particle) jumps up, and then back down, between energy levels (orbits). This up & down -- maximum to minimum -- action produces waveforms on an oscilloscope. But the actual jumps seem to occur almost instantaneously. So, what if we imagine them as quantum leaps without passing through the space (nothingness) in between. In that case, the pattern would look more like a series of dots than a sine wave curve. {see image below} — Gnomon

I don't think this concept of nothingness works, because it renders what you call the quantum leap as unintelligible, impossible to understand. It may be the case that it actually is unintelligible, that is a real possibility, but we ought not take that as a starting premise. We need to start with the assumption that the medium is intelligible, then we'll be inspired to try to understand it, and only after exhausting all possible intelligible options should we conclude unintelligibility, nothingness. -

wonderer1

2.4kAs you've made a claim that 'Meaning depends on a physical interpretive context' so I'm asking, what do you mean by that? — Wayfarer

wonderer1

2.4kAs you've made a claim that 'Meaning depends on a physical interpretive context' so I'm asking, what do you mean by that? — Wayfarer

The state of a brain seems a pretty key factor.

But how does it come to be so encoded, what is it that does the encoding and what interprets the code? I think you will find that they are very big questions, so I'm not trying to elicit an answer - like Feynmann says! - so much as a recognition that the answer is not obvious, and also not something that can be understood in terms of physics. — Wayfarer

Yeah, a lot of other sciences besides physics are important in developing understanding. So yes they are big questions with complicated explanations. Work on answering them is ongoing.

As far as I can discern, the only instances of codes are the biological code - DNA - and in languages. — Wayfarer

We can apply our ability to interpret to things other than codes. For example fossils. -

Tom Storm

10.9kYes, but this is an argument about what is good, and presupposes a desire for the good in both parties. You are saying to the divine command theorist, "You see divine commands as good, but they are not truly good. This other thing is truly good, and it is this that you ought to seek instead." — Leontiskos

Tom Storm

10.9kYes, but this is an argument about what is good, and presupposes a desire for the good in both parties. You are saying to the divine command theorist, "You see divine commands as good, but they are not truly good. This other thing is truly good, and it is this that you ought to seek instead." — Leontiskos

I can see this. But I'd not be saying that. I'd be asking questions: "Do you accept something as good because you think good wants it? Then how do you know God wants it? How do you demonstrate that this is the correct interpretation of God's will? Did you consider your thinking about this or did you merely accept what you were told by a priest or family member?

The questions are really endless and this last perspective seems close to nihilism to me. There is a total disengagement between making a decision to do good as opposed to following some instruction which you don't even know to be true. But yes, I get that there is still rudimentary reasoning happening, even if it is fallacious and, perhaps, complacent.

My quip about god being evil need not enter into this and in most discussions would not. It's enough to be getting on with trying to demonstrate how anyone can know what god/s wants. Whether good nature is goodness itself is for a separate line enquiry. -

Janus

18kI tend to think there is a complex interrelation between ideation and experience. — Leontiskos

Janus

18kI tend to think there is a complex interrelation between ideation and experience. — Leontiskos

I don't doubt that.

Like ↪Wayfarer, I do not read Hadot this way. I think Hadot sees discourse and practice as two poles that mutually influence one another, and he critiques the undue emphasis on discourse in modern philosophy, but I don't see him claiming that practice subsumes or displaces discourse. Or in other words, forms of philosophical practice are in some ways as vulnerable to argumentation as philosophical discourse is. The renewed emphasis on practice creates a more holistic philosophical environment; but it doesn't make argument futile. — Leontiskos

I haven't said that discourse and practice don't influence one another, and I don't take Hadot to be saying that practice subsumes discourse, either. I see the relation between discourse and practice as being something like this: for each kind of spiritual practice there will be some discourse appropriate to, and supportive of, that practice.

I think this is unarguable when you look at the different discourses associated with, for example Stoicism, Neoplatonism, Epicureanism, Buddhism, Vedanta, various kinds of Yoga, Daoism, Zen and so on. Of course, there will also be commonalities, since the altered states of consciousness will, being human phenomena, necessarily share some commonalities.

It is the interpretations of the significance of those altered states vis a vis the different metaphyseal ideas like God, karma, rebirth, resurrection, Brahman, Boddhisatvas that show the various culturally mediated contexts that shape those metaphysical ideas that I find questionable.

My claim is that those altered states and their various cultural interpretations underdetermine the various metaphysical beliefs associated with them.

It seems crucial to assert that the intrinsically valuable (ends in themselves) are a proper subject of argument. I think that is where we disagree. I think we must argue about the highest things. — Leontiskos

This is where we disagree because I see no reason to believe that there are any intrinsically valuable things. I think there are certain values which reflect necessary pragmatic concerns for any community, the main moral principles which are to be found in almost any community, but that is about as far as I would go. I cannot see any demonstrable or decidable otherworldly criteria that could justify believing in intrinsic overarching metaphysical values.

So, I think it all comes down to faith, and I have no argument with that. Why must we argue about "higher things" when it is not rationally, logically or empirically demonstrable that there are in fact any higher things? This would seem to be just your and other believers' preference or intuitve feeling, which is fine, provided it is acknowledged that that is what it is.

If believers discuss such things with other believers of like mind, then there will be little argument, and the participants may benefit from discussion, but that is different than arguing with those, whether unbelievers or differently oriented believers, about whose metaphysical beliefs is right. That is what constitutes fundamentalism and would seem to me to be at best "pouring from the empty into the void" and at worst stoking the fires of divisiveness. -

Leontiskos

5.6kMy claim is that those altered states and their various cultural interpretations underdetermine the various metaphysical beliefs associated with them. — Janus

Leontiskos

5.6kMy claim is that those altered states and their various cultural interpretations underdetermine the various metaphysical beliefs associated with them. — Janus

I agree with this. Are you not also saying that the altered states are primary or prior, and the metaphysical beliefs are derivative or posterior?

This is where we disagree because I see no reason to believe that there are any intrinsically valuable things. — Janus

I gave the example of music, and the appreciation of music. Do you hold that this is not intrinsically valuable, and is instead only a means to an end? -

Janus

18kI agree with this. Are you not also saying that the altered states are primary or prior, and the metaphysical beliefs are derivative or posterior? — Leontiskos

Janus

18kI agree with this. Are you not also saying that the altered states are primary or prior, and the metaphysical beliefs are derivative or posterior? — Leontiskos

Yes, I would agree with tthat.

I gave the example of music, and the appreciation of music. Do you hold that this is not intrinsically valuable, and is instead only a means to an end? — Leontiskos

There are people, perhaps not many, who don't like music. If we accept that almost everyone likes some kind of music, althought their tastes may vary considerable, then I would say that for those people liistening to (their preferred) music certainly has value for them. -

Wayfarer

26.2kWhy must we argue about "higher things" when it is not rationally, logically or empirically demonstrable that there are in fact any higher things? — Janus

Wayfarer

26.2kWhy must we argue about "higher things" when it is not rationally, logically or empirically demonstrable that there are in fact any higher things? — Janus

Here is where I say that you echo positivism. You tend to set the limitations of your own personal worldview as the yardstick for what others might or should think is reasonable. -

Leontiskos

5.6kI guess in your "not only that" space you might come at this from a more platonic perspective? For me The Good is an artifact of human experience and reasoning and can only be contingent, even if there are large intersubjective communities of agreement. The experience of being human doesn't differ all that much in terms of most people wanting to flourish and avoid suffering. — Tom Storm

Leontiskos

5.6kI guess in your "not only that" space you might come at this from a more platonic perspective? For me The Good is an artifact of human experience and reasoning and can only be contingent, even if there are large intersubjective communities of agreement. The experience of being human doesn't differ all that much in terms of most people wanting to flourish and avoid suffering. — Tom Storm

"Not only that" in the sense that good is not man-made. For example, food is good for man, and this truth is not man-made. But I realize you disagree with this and that it will lead us off on a tangent, which is why I bracketed it.

The primary point is that good relates to psychological motive. Maybe it could be put this way: if someone believes that there is no reason to do this or that or anything, then they will be without purpose. That is the separation of reason from the good.

The questions are really endless and this last perspective seems close to nihilism to me. There is a total disengagement between making a decision to do good as opposed to following some instruction which you don't even know to be true. But yes, I get that there is still rudimentary reasoning happening, even if it is fallacious and, perhaps, complacent. — Tom Storm

Well, there is reasoning occurring and generally in this case the good and reason will not be divorced. That said, fideism does separate reason from the good, and some divine command theorists are fideists. -

Janus

18kHere is where I say that you echo positivism. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kHere is where I say that you echo positivism. — Wayfarer

Trying to dismiss what I say by associating it with a philosophical position I don't hold is both a red herring, and a strawman. If you want to take issue with what I said, then present a rational, logical or empirical argument that purports to show that there must be, or at least that we should believe there are, higher things, higher things which can be determined to be such and such, not merely an ineffable experience or feeling.

Your dislike of positivism (which I share, although probably not for the same reasons) and your preference for the idea that there must be higher things do not constitute such an argument. -

Tom Storm

10.9kFor example, food is good for man, and this truth is not man-made. But I realize you disagree with this and that it will lead us off on a tangent, which is why I bracketed it. — Leontiskos

Tom Storm

10.9kFor example, food is good for man, and this truth is not man-made. But I realize you disagree with this and that it will lead us off on a tangent, which is why I bracketed it. — Leontiskos

Got ya... Yep, I don't think this can be demonstrated. But let's explore this in a more appropriate place some other time. Thanks for the chat. :up:

If you want to take issue with what I said, then present a rational, logical or empirical argument that purports to show that there must be, or that we should believe there are, higher things, and which can be determined to be such. — Janus

Quite the question. I think the primary reasoning or justification available would be some kind of appeal to tradition - Platonism, the perennial philosophy and what not. -

Janus

18kQuite the question. I think the primary reasoning or justification available would be some kind of appeal to tradition - Platonism, the perennial philosophy and what not. — Tom Storm

Janus

18kQuite the question. I think the primary reasoning or justification available would be some kind of appeal to tradition - Platonism, the perennial philosophy and what not. — Tom Storm

Right, but appeal to authority is universally regarded as a philosophical fallacy. Even Gautama said so, reportedly. -

Leontiskos

5.6kYes, I would agree with tthat. — Janus

Leontiskos

5.6kYes, I would agree with tthat. — Janus

Okay, so that's where I think we would end up disagreeing. I don't think that phenomenon is absent from religion, but I don't think it explains all metaphysical beliefs. I am also not convinced that such is Hadot's view, but that is somewhat arguable.

There are people, perhaps not many, who don't like music. If we accept that almost everyone likes some kind of music, althought their tastes may vary considerable, then I would say that for those people liistening to (their preferred) music certainly has value for them. — Janus

Okay good, and I conclude that listening to music is intrinsically valuable (for some, or most). Obviously this also exists at a cultural level, from Gregorian chant, to Beethoven, to Radiohead. Such composers aim to produce something that is intrinsically valuable, and which will be chosen as an end in itself.

Music, then, becomes a value and an object of discourse, even when conceived as an end:

So take for example the end of appreciating music. I think we can speak about this end, argue about it, learn about it, teach it, seek it, honor it, etc. Once we understand this end we can then speak/argue/learn/teach/seek/honor the proper means, such as technical proficiency, discernment of quality, etc. Nevertheless, the act of music appreciation is not publicly demonstrable in any obvious way, largely because appreciation is not the sort of thing done for the sake of demonstration. It would be incongruous to try to demonstrate appreciation (because demonstration pertains to means and appreciation pertains to ends). — Leontiskos

The idea here is that there are two kinds of human acts: acts which are instrumentally valuable (means), and acts which are intrinsically valuable (ends). So if someone tells me that there are no intrinsically valuable things, I must infer that there are also no instrumentally valuable things.

I think this is actually what is happening on a large scale: the culture tells us that there are no intrinsically valuable things, and the logical conclusion is that there are also no instrumentally valuable things (and this leads to a form of nihilism—more or less the form that I have been discussing with @Tom Storm). -

Leontiskos

5.6kRight, but appeal to authority is universally regarded as a philosophical fallacy. — Janus

Leontiskos

5.6kRight, but appeal to authority is universally regarded as a philosophical fallacy. — Janus

A relatively weak argument, not a fallacy. This is a rather important distinction, even though the argument from authority has little to do with the topic at hand. One needs no argument from authority to see that music is intrinsically valuable, or that ends are "higher things" than means.

---

But let's explore this in a more appropriate place some other time. Thanks for the chat. :up: — Tom Storm

Sounds good. :up: -

Wayfarer

26.2kTrying to dismiss what I say by associating it with a philosophical position I don't hold is both a red herring, and a strawman — Janus

Wayfarer

26.2kTrying to dismiss what I say by associating it with a philosophical position I don't hold is both a red herring, and a strawman — Janus

The statement quoted already was right out of the positivist playbook.

Positivism: a philosophical system recognizing only that which can be scientifically verified or which is capable of logical or mathematical proof, and therefore rejecting metaphysics and theism.

More about Hadot:

Hadot’s founding meta-philosophical claim is that since the time of Socrates, in ancient philosophy “the choice of a way of life [was] not . . . located at the end of the process of philosophical activity, like a kind of accessory or appendix. On the contrary, its stands at the beginning, in a complex interrelationship with critical reaction to other existential attitudes . . .” (WAP 3). All the schools agreed that philosophy involves the individual’s love of and search for wisdom. All also agreed, although in different terms, that this wisdom involved “first and foremost . . . a state of perfect peace of mind,” as well as a comprehensive view of the nature of the whole and humanity’s place within it. They concurred that attaining to such Sophia, or wisdom, was the highest Good for human beings. — Philosophy as a Way of Life

Also, in response to your frequent argument that 'as all religions differ, and all make exclusive claims to truth, then how can you say that any of them might have a hold of it?', see this paper by John Hick, well-known philosopher of religion and defender of pluralism, Who or What is God?

What does this mean for the different, and often conflicting, belief-systems of the religions? It means that they are descriptions of different manifestations of the Ultimate; and as such they do not conflict with one another. They each arise from some immensely powerful moment or period of religious experience, notably the Buddha’s experience of enlightenment under the Bo tree at Bodh Gaya, Jesus’ sense of the presence of the heavenly Father, Muhammad’s experience of hearing the words that became the Qur’an, and also the experiences of Vedic sages, of Hebrew prophets, of Taoist sages. But these experiences are always formed in the terms available to that individual or community at that time and are then further elaborated within the resulting new religious movements. This process of elaboration is one of philosophical or theological construction -

Leontiskos

5.6kBut can they be subject to philosophical discourse? — Wayfarer

Leontiskos

5.6kBut can they be subject to philosophical discourse? — Wayfarer

Right. :up: This gets into Liberalism debates, such as Peter L. P. Simpson's "Political Illiberalism." It is similar to 's point about political philosophy vs. political science. The English philosophical tradition is reticent to discourse about ends, and especially political ends.

(Links to Simpson's <website>, <academia page>) -

Wayfarer

26.2kSo how can the information be physical?

Wayfarer

26.2kSo how can the information be physical?

— Wayfarer

By being encoded in the structure of physical stuff.

Why think there is information available to us, other than that which can come to us via configurations of physical stuff? — wonderer1

All kinds of things. A lot of what we nowadays take for granted, or at least, see around us all the time, not long ago only existed in the domain of the possible, penetrated by the insights of geniuses who navigated a course from the possible, the potential, to the actual, by peering into that domain, which at the time did not yet exist, and then realising it, in the sense of 'making it real'. One parameter of that is physical, and it's an important parameter, but not the only one.

Superb piano music on that site. (That's as far as I've gotten.) -

Gnomon

4.4k

Gnomon

4.4k

Quantum leaps seem to be inherent in the foundations of the physical world, as revealed by 20th century sub-atomic physics. In the 17th century, Isaac Newton assumed that physical processes are continuous, but the defining property of Quantum Physics is discontinuity. When measured down to the finest details, Energy was found to be, not an unbroken fluid substance, but could only be measured in terms of isolated packets, that came to be called "quanta"*1. Yet, on the human scale, the brain merges the graininess of Nature into a smooth image. There's nothing spooky about that. If you put your face up close to your computer screen, you will see a bunch of individual pixels. But as you move away, those tiny blocks of light merge into recognizable images.I don't think this concept of nothingness works, because it renders what you call the quantum leap as unintelligible, impossible to understand. It may be the case that it actually is unintelligible, that is a real possibility, but we ought not take that as a starting premise. We need to start with theassumption that the medium is intelligible, then we'll be inspired to try to understand it, and only after exhausting all possible intelligible options should we conclude unintelligibility, nothingness. — Metaphysician Undercover

So yes, until the early twentieth century, scientists had always "assumed" the material "medium" they were studying would be "intelligible" --- no philosophical speculation required. But the quantum pioneers --- using technological extensions of their senses --- began to "put their faces up close" to material objects. And they were perplexed by the non-mechanical nature of the microcosm of the material world. Bohr, Planck, etc found the observed quanta & quantum leaps to be "unintelligible", and characterized by inherent Relativity & Uncertainty*2.

This nonsense flew into the face of their traditional authority on Physics : the commonsensical, deterministic, and absolute concepts of Newtonian mechanics. Ironically, in their efforts to understand what they were seeing, they reintroduced previously banished Philosophy into the laboratory*3. Subsequently, Science experienced a split --- Practical vs Theoretical --- similar to the Protestant rejection of the authority of the Catholic Church. In this case, the Authority was Newton. Even today, philosophers tend to take sides : favoring either Classical Determinism & Materialism or Quantum Superdeterminism*4 & Idealism. Yet on the whole, reality may actually be a confusing admixture, similar to oil & water, that combine to form a smooth cream.

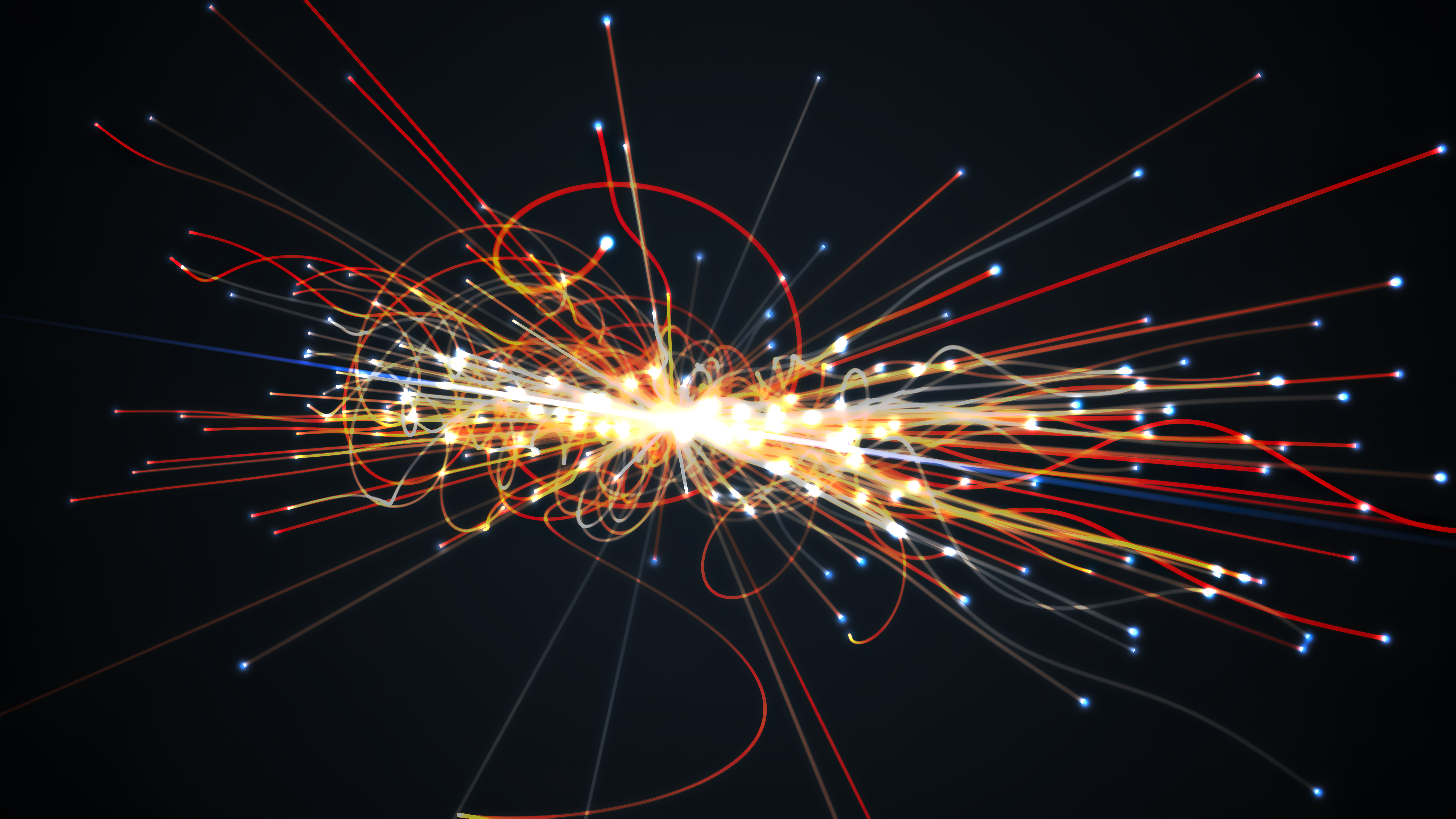

Due to the "spooky action at a distance" that annoyed Einstein, sub-atomic physics defies common sense. But pragmatic physicists gradually learned to accept that Nature did not necessarily play by our man-made rules. So, unlike impractical philosophers, they decided to "just shut-up and calculate". Consequently, post-quantum physics became mostly theoretical and mathematical, and little one-man labs were replaced by billion-dollar cyclotrons with thousands of mathematicians attempting to interpret the cryptic evidence produced by smashing particles together in intentional traffic accidents. {see image below}

Regarding, "exhausting all possible intelligible options", I recommend the book summarizing Werner Heisenberg's Nobel addresses : Physics and Philosophy, The Revolution in Modern Science. There, he reviews many of the alternative interpretations that quantum pioneers sifted through in their attempts to make sub-atomic reality "intelligible". :smile:

*1. Quanta : a discrete quantity of energy proportional in magnitude to the frequency of the radiation it represents. ___Oxford

*2. That Old Quantum Theory :

Einstein's two theories of relativity have shown us that when things move very fast or when objects get massive, the universe exhibits very strange properties. The same is also true of the microscopic world of quantum interactions. The deeper we delve into the macrocosm and the microcosm, the further we get away from the things that make sense to us in our everyday world.

https://www.infoplease.com/math-science/space/universe/theories-of-the-universe-that-old-quantum-theory

*3. Understanding and Interpreting Contemporary Science :

Quantum Philosophy is a profound work of contemporary science and philosophy and an eloquent history of the long struggle to understand the nature of the world ...

https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt46n407

*4. Superdeterminism :

Quantum mechanics is perfectly comprehensible. It’s just that physicists abandoned the only way to make sense of it half a century ago.

https://nautil.us/how-to-make-sense-of-quantum-physics-237736/

Note --- This approach to quantum weirdness is essentially holistic, in the sense that everything is entangled with everything else. The parts are quantized, but the whole system (e.g. Cosmos) is integrated and interactive, functioning as a unity.

IS THIS PIECE OF REALITY INTELLIGIBLE ?

Strange pattern found inside world’s largest atom smasher

-

Gnomon

4.4k

Gnomon

4.4k

I assume that the "older kind of philosophy" referred to those like Aristotle, who wrote the book on factual Physics. But even he wrote a book on speculative Metaphysics. Today, modern Science is dedicated to understanding material Reality, and disdains philosophical attempts to understand mental Ideality. Even the "soft" science of Psychology is based primarily on an empirical model, and eschews theoretical models. Except in cases where the mechanical models don't work : the neural-net model is a dead-end*1. In which case, Mathematical models like IIT, or Information models, are used to go beyond mechanics to understand the mind philosophically as a whole system.Hadot's point, as I understand it, is that the older kind of philosophy, which was not about argumentation and asserting anything, has been lost. I don't know if that's true; there may be practicing Stoics, Neoplatonists and Epicureans for all I know. To repeat, the point of such philosophies is about practice and not about proving any metaphysical theory. I'm not saying they have no value; obviously they have value to those who want to practice them. — Janus

A common answer to the question : "what is the point of philosophy"*2*3 is "to find the truth". Hence, the Greeks posited Universal Principles, which are in practice unverifiable, but are in principle provable, just as mathematical theorems can be proven to be consistent with Logic. Mathematical "truths" (e.g statistical probabilities) cannot be empirically confirmed, but scientists typically accept them as authoritative. Since physical experiments are always limited to a narrow selection of instances, the universal application of mathematics serves to generalize their subjective interpretations of empirical observations. Generalizing is the point of Philosophy ; what it does.

Your practical definition of "the point" of speculative Philosophy sounds more applicable to pragmatic Science. Philosophy seeks What's Logical (math ; meaning : values), while Science seeks What Works (instrumental). Newton's mechanical physics (transfer of force by contact) was workable, in the sense that it opened up a new path for the Industrial Age. But Bohr's non-mechanical physics (spooky action at a distance) opened-up a path to the Information Age. Computers are useful tools, even though they have no gears transmitting force from cog to cog. Instead, it transmits ideas from mind to mind, by means of immaterial bits chaining together only by logical relationships (math). Therefore, modern seekers can take a hint from Aristotle, who followed his Physics, with a separate addendum on Metaphysics*4. :nerd:

*1.A. Minding the Brain: Models of the Mind, Information, and Empirical Science :

Their provocative conclusion? The mind is indeed more than the brain.

https://www.amazon.com/Minding-Brain-Information-Empirical-Science/dp/163712029X

*1.B. Contemporary Artificial Neural networks are a (very profitable) dead end.

The dead end in neural network research . . . .

https://floriandietz.me/neural_networks_dead_end/

*2. What Is Philosophy's Point? :

What is philosophy? What is its purpose? Its point? The traditional answer is that philosophy seeks truth. But several prominent scientists, notably Stephen Hawking, have contended that philosophy has no point, because science, a far more competent truth-seeking method, has rendered it obsolete.

https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/cross-check/what-is-philosophys-point-part-1-hint-its-not-discovering-truth/

Note --- The practical Facts of Science are only "true" in specific physical contexts. But the Truths of Philosophy are universally applicable to general metaphysical (immaterial) contexts. Science has eminent domain for practical "How" questions. But Philosophy is the go-to method for speculative "Why" questions. So their authority is limited to "non-overlapping magisteria".*4

*3. What's the point of Philosophy? :

Philosophy is about finding truth. It deals in absolutes. Science deals in probabilities, tentative speculation.

https://www.reddit.com/r/askphilosophy/comments/3dybao/whats_the_point_of_philosophy/

*4. Science versus Philosophy :

Premise of Gould's position is NOMA: Non-Overlapping Magisteria (domains). Conflict between science and religion is FALSE - science covers empirical realm (what the universe is made of, or fact) while religion extends over the ultimate meaning and moral value of life.

https://serc.carleton.edu/sp/library/sac/examples/gould.html

Note --- In the context of this thread, "religion" is applied philosophy, which uses universal truths to control minds by means of beliefs. By contrast, Stoicism assumed a universal law (Zeus) immanent in Nature, and applied that belief to personal questions, such as "how ought one to live". And it taught self-control to independent-minded persons, requiring no political institutions or organizations to rule the minds of men by Faith. Was it a Religion, or a Philosophy?

Note 2 --- See Science is not "The Pursuit of Truth" https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/14720/science-is-not-the-pursuit-of-truth

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum