-

Wayfarer

26.1kThe neurons of the central nervous system terminate in mechanical switches — apokrisis

Wayfarer

26.1kThe neurons of the central nervous system terminate in mechanical switches — apokrisis

Despite the appeals to semiosis, signs and meaning, C S Peirce, you default to physicalism where it counts. Who or what presses these buttons, and to what end? That is a philosophical problem, not a question of bio-engineering.

His account often mentions, and is compatible with, QBism, which is not the realist theory in the sense that you insist on.

he has a book to sell, a name to make. There is a social incentive for him to angle his story so as to attract the audience he does. — apokrisis

And that's a blatant ad hom, he's just a shabby opportunist. There are a lot of things I question about his account, but that's not one. -

apokrisis

7.8kWho or what presses these buttons, and to what end? — Wayfarer

apokrisis

7.8kWho or what presses these buttons, and to what end? — Wayfarer

The model does. You have your embodied self-world relation and I have mine.

At a neurobiological level that means you push your buttons and I push mine. But then at a sociocultural level of semiotic order, we get to push each other’s buttons as we argue over the acceptable community model of our collective reality. :grin:

His account often mentions, and is compatible with, QBism, which is not the realist theory in the sense that you insist on. — Wayfarer

So much the worse then. If he were more focused on the nervous system in terms of its actual mechanical interface with reality, he might instead say something more interesting about how the new discoveries in quantum biology explain stuff like how noses can read scents off chemical structures.

And that's a blatant ad hom, he's just a shabby opportunist. — Wayfarer

If it looks like a duck and quacks like a duck then likely it is a duck. Or in this case, another ducking quack. -

Wayfarer

26.1kYeah, well. I'm not all in on him, but still positively disposed. But I still think Mind and the Cosmic Order, Charles S Pinter, is a superior book covering very similar territory, and much more philosophically coherent. (And probably, sadly, forever unsung.)

Wayfarer

26.1kYeah, well. I'm not all in on him, but still positively disposed. But I still think Mind and the Cosmic Order, Charles S Pinter, is a superior book covering very similar territory, and much more philosophically coherent. (And probably, sadly, forever unsung.) -

apokrisis

7.8kPragmatism is the art of being finely balanced on the metaphysical knife edge between the competing pulls of lumpen realism and lumpen idealism.

apokrisis

7.8kPragmatism is the art of being finely balanced on the metaphysical knife edge between the competing pulls of lumpen realism and lumpen idealism.

Even as cognitive science moves itself towards that precise middle ground between the two, folk seem still able to slither away down their preferred side and proclaim victory for their chosen lumpen view.

So enactivism is being misused as the gateway drug to idealism now. And QBism apparently too. -

Wayfarer

26.1klumpen idealism. — apokrisis

Wayfarer

26.1klumpen idealism. — apokrisis

I know an oxymoron when I see it.

You should look into Pinter's book. The reason I say it will be unsung, is because it was a labour of love on his part, he's a mathematics emeritus - now deceased - who in the last part of his very long life devoted considerable energy to cognitive science. But as he's not published in that field - all his previous books were on algebra and the like, JGill knows them - nobody in the field paid much attention to his Mind and the Cosmic Order, which I think is a shame. He doesn't push an idealist barrow, although I think his book provides some grounds for it. I don't think you would see it as incompatible with your biosemiotic philosophy. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI bought the Kindle edition for a lot less than that. Anyway, never mind, I won't try and sell it. I cover some of the details in the mind-created world thread.

Wayfarer

26.1kI bought the Kindle edition for a lot less than that. Anyway, never mind, I won't try and sell it. I cover some of the details in the mind-created world thread. -

hypericin

2.1kIt's a mistake to say that brains do anything - that is what is described in Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience as the 'mereological fallacy', attributing to the part what only a whole is capable of. — Wayfarer

hypericin

2.1kIt's a mistake to say that brains do anything - that is what is described in Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience as the 'mereological fallacy', attributing to the part what only a whole is capable of. — Wayfarer

Is it a mistake to say that hearts pump blood? Only a whole organism is capable of sustaining blood circulation, not an isolated heart. Yet that is the function of the heart within the whole organism. -

Wayfarer

26.1kIs it a mistake to say that hearts pump blood? — hypericin

Wayfarer

26.1kIs it a mistake to say that hearts pump blood? — hypericin

Not in the context of physiology and anatomy, but it’s not an apt comparison with cognition and judgement. It appeals to the supposed authority of neuroscience to make philosophical claims about the mind - very different thing to the circulation of blood. -

Apustimelogist

946

Apustimelogist

946

I honestly don't see inherent differences in any kind of knowledge whether scientific or everyday, just some choose to use vaguer words or reify vague, nebulous hunches. For many of the things I am interested in, that's not interesting. Maybe if I want to analyse music, film or art that is how I would do it. For me, philosophy is a product of the mind and ultimately brain. And insofar as we want clarity in models of how the mind and brain works, I want philosophy - which sits on the shoulders of a functioning brain / mind - to adhere to that. I feel like when going in the opposite direction, its more about clinging onto some kind of spirituality and humanism rather than as clear a view of things as possible... perhaps because deconstructing the mind is perceived as a threat to humanism. People want to hold onto words like "agency" and "rationality" and "subjectivity" without analyzing what they mean because they fear it deconstructs their humanity. -

hypericin

2.1kNot in the context of physiology and anatomy, but it’s not an apt comparison with cognition and judgement. It appeals to the supposed authority of neuroscience to make philosophical claims about the mind - very different thing to the circulation of blood. — Wayfarer

hypericin

2.1kNot in the context of physiology and anatomy, but it’s not an apt comparison with cognition and judgement. It appeals to the supposed authority of neuroscience to make philosophical claims about the mind - very different thing to the circulation of blood. — Wayfarer

I'm not sure what the philosophical claims are supposed to be. That the brain integrates sensory information and acts upon it seems to be no less an empirical claim than that the heart pumps blood. Nor was I aware there was a special authority required to make philosophical claims. Maybe we should be verifying everyone's philosopher cards here. -

Apustimelogist

946

Apustimelogist

946

I agree there with wayfarer there is a difference in these examples. In the heart example, what is being talked about is a single anatomical context or perspective within which heart and blood co-exist and interact directly.

But various claims in the mereological fallacy link talk about things like "decision", "belief", etc. which cannot be defined directly in terms of brain content. Infact, they surely would exist if people didn't know about brains and are learned from experiences of what we do as people as a whole. In a complementary way, I guess, it is difficult talk about what brains do in a complete way without referring to their consequences on the outside world and inputs going in.

I think interpreting these "mereological fallacies" depends on your philosophy of mind, and much of it is possibly about expediency to avoid pedantry. But maybe this just reflects the difference between a cognitive neuroscientists more interested in experimental studies relating brain variables and behavior, as opposed to a philosopher more interested in conceptual clarity. -

Wayfarer

26.1kNor was I aware there was a special authority required to make philosophical claims. Maybe we should be verifying everyone's philosopher cards here. — hypericin

Wayfarer

26.1kNor was I aware there was a special authority required to make philosophical claims. Maybe we should be verifying everyone's philosopher cards here. — hypericin

An important part of philosophy is criticism, especially of poor analogies and misapplied categories.

People want to hold onto words like "agency" and "rationality" and "subjectivity" without analyzing what they mean because they fear it deconstructs their humanity. — Apustimelogist

And I see you as reflexively hanging on to something like scientism, the belief that philosophy must always defer to the white lab coat of scientific authority. To ‘deconstruct’ the mind is to analyse it in terms of something else, or of its constituent elements - the impossibility of which is precisely the point of Chalmer’s ‘facing up to the problem of consciousness’ article. I don’t want to thrash all that out again, but nothing you’re saying indicates that you are facing up to that problem. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

The fact that it is information arising from the processing in a neural network which has inputs which are largely the outputs of sensory nerves. (E.g. the optic nerves for vision, the olfactory bulb for smell, whatever nerves carry signals away from the cochleas for hearing.)

But neural networks run on PCs are not concious, right? So being a neural network and processing outputs and inputs isn't enough, even if these outputs come from the environment via photoreceptors, microphones, etc.

So again the appeal to the data/organ being of a "sensory" sort seems to do all the explaining. Why is an eye a sensory organ but the camera on a self-driving car isn't? It seems to me that the difference is that the former involves sensation. But then it looks like all we have done is explain what has conciousness by appeal to a term that implies something is concious.

And yet modern AI does such modelling, presumably without consciousness. I think what makes brains conscious is that they are general informational processors whose interface to the world is the result of the modelling of sensory information you are talking. To brains, as far as they/we are concerned, such models are the subjective plentitudes we experience, they/we are wired to interface with the world in this way. Just as computers run on symbolic logic, our wet "computers" "run" on sensory experiences: we perceive, feel, imagine, and think to ourselves, all of which are fundamentally sensorial. It is these and only these sensations, externally and internally derived, that we are aware of, every other brain process is unconscious to us.

I think something very much like this might be true, but the appeal to "sensory" information seems to be doing the explanatory lifting here. Yet what makes something "sensory" information? A combat drone uses video, IR, radar, etc. inputs to get information about the world. It puts this information into a model. But presumably this isn't "sensory" information because it doesn't involve sensation.

If the term "sensory" does the heavy lifting in our explanation of conciousness it seems like we need to describe how to identify "sensory information" without reference to sensation itself. Otherwise we end up saying something like "experiencing entities experience because they receive experiential information from the enviornment or have an experiential relationship to it."

"Modeling relationships," might be another tricky term here. Does a dry river bed model past flow of rainwater? We probably wouldn't want to say that, but it certainly does contain information about past rainfall. -

Apustimelogist

946

Apustimelogist

946

And I see you as reflexively hanging on to something like scientism, the belief that philosophy must always defer to the white lab coat of scientific authority. — Wayfarer

I think its more about trying to be as clear as possible. I think its about the idea that there is an objective way the world is and the mind is embedded within that. It is a slave to other partsof the objective world that undergird it, not independent from those things; the evidence relating our minds to neurons and physics is overwhelming. There is no harm trying to clarify that relationship as precisely as possible.

To ‘deconstruct’ the mind is to analyse it in terms of something else, or of its constituent elements - the impossibility of which is precisely the point of Chalmer’s ‘facing up to the problem of consciousness’ article. — Wayfarer

Not necessarily, because I think you can analyze the mind from a completely experiential perspective by the same kind of paradigm.

the impossibility of which is precisely the point of Chalmer’s ‘facing up to the problem of consciousness’ article. — Wayfarer

For me, not solving the hard problem doesn't mean that the mind is not still embedded in an objective world and in someways enslaved by the smaller scales of that objective reality.

We may just be limited in the questions we can ask and the answers we can get. All our explanations, scientific or not, are models enacted within the limits of our experiences, the limits of what brains can do. In sympathy with the illusionist, I think there may just be an inability for a mind or brain to explain certain things about itself in a substantial way. Similarly, science cannot tell us anything about the fundamental "intrinsic nature" of things beyond experience. -

AmadeusD

4.2kSimilarly, science cannot tell us anything about the fundamental "intrinsic nature" of things beyond experience. — Apustimelogist

AmadeusD

4.2kSimilarly, science cannot tell us anything about the fundamental "intrinsic nature" of things beyond experience. — Apustimelogist

I think this is true - but then whence comes:

there is an objective way the world is and the mind is embedded within that — Apustimelogist

These seem to run into each other quite violently... -

Apustimelogist

946

Apustimelogist

946

These seem to run into each other quite violently... — AmadeusD

I disagree. For instance, I don't need to know what is happening on the slopes of Mount Everest right now to believe there are some definite events happening on the slopes of Mount Everest right now. -

wonderer1

2.4kBut neural networks run on PCs are not concious, right? So being a neural network and processing outputs and inputs isn't enough, even if these outputs come from the environment via photoreceptors, microphones, etc. — Count Timothy von Icarus

wonderer1

2.4kBut neural networks run on PCs are not concious, right? So being a neural network and processing outputs and inputs isn't enough, even if these outputs come from the environment via photoreceptors, microphones, etc. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Right. I expect anyone working on an embodied AI, which is structured to learn from embodied experience, is in an at least somewhat secretive lab. (Likely with military funding.) I don't think the hardware is there, to make this a reality real soon, but of course having a jump on the research when a new generation of hardware platforms arrives could provide a big strategic advantage.

(And if I disappear soon, and am never heard from again, you will know I was right.) :wink:

So again the appeal to the data/organ being of a "sensory" sort seems to do all the explaining. Why is an eye a sensory organ but the camera on a self-driving car isn't? It seems to me that the difference is that the former involves sensation. But then it looks like all we have done is explain what has conciousness by appeal to a term that implies something is concious. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I'm simply coming into the discussion thinking of eyes, cochleas, and olfactory bulbs as sensors. So I think it makes sense to consider the subset of neural networks in the brain, which primarily take input that is the output of sensors, to be neural networks that output sensory information. Sensation would be the result of further information processing by later stage neural networks which meld the sensory data with deep learning from other neural networks to yield sensations. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI think its about the idea that there is an objective way the world is and the mind is embedded within that. — Apustimelogist

Wayfarer

26.1kI think its about the idea that there is an objective way the world is and the mind is embedded within that. — Apustimelogist

All well and good - but that also embodies a perspective, somewhere outside both the mind and the world. A mental picture, if you like, or image of the self-and-world.

What Hoffman et al are doing is actually de-constructing that sense - which is what you yourself said in an earlier post! I'm slogging through his book, and there's a lot of data from cognitive science and evolutionary biology. But through that he's arriving at the counter-intuitive insight that the brain/mind in essence constructs the world which we reflexively believe is 'out there'. And there's a lot of pushback on that point, because it undermines our instinctive sense of what's real. Hoffman himself says in an interview that he finds it difficult to really accept the implications of his own theory!

the evidence relating our minds to neurons and physics is overwhelming. — Apustimelogist

But is it? Who are the case studies for that view? I know of a clique of academic philosophers who are customarily associated with pretty hard-edged materialist theories of mind: they are P & P Churchland, a married couple who are both academics, Alex Rosenberg, and the late Daniel Dennett are frequently mentioned in this regard. They were very much the target of David Chalmer's argument, and I think the argument succeeds. (There are also naturalist philosophers of mind, like John Searle, who are critical of the materialists, it was Searle who dubbed Dennett's book Consciousness Explained as 'Consciousness Explained Away'.)

But going back to the point I made above, brains and neurons and physics are themselves mental constructs, in some fundamental sense. It doesn't mean they're 'all in the mind' in an obvious or gross kind of way, but that the mind (or the observer) imputes meaning and value to the terminology and principles of those sciences. So there is a fundamentally mental or subjective element to those theories, which is never disclosed, because they're not critically aware of them. They impute to the objective and external what is really being generated by the mind. So there's a vicious circle at back of it, the attempt for science to explain itself. Kant was aware of that in a way the above philosophers can never be.

Similarly, science cannot tell us anything about the fundamental "intrinsic nature" of things beyond experience. — Apustimelogist

But it's a question philosophy must grapple with. So if we continue to operate within the boundaries of empiricism it's fair to question whether we really are engaging with philosophy.

I don't need to know what is happening on the slopes of Mount Everest right now to believe there are some definite events happening on the slopes of Mount Everest right now. — Apustimelogist

By bringing them to mind! You can't say anything about them, unless you do that. -

AmadeusD

4.2kI disagree. For instance, I don't need to know what is happening on the slopes of Mount Everest right now to believe there are some definite events happening on the slopes of Mount Everest right now. — Apustimelogist

AmadeusD

4.2kI disagree. For instance, I don't need to know what is happening on the slopes of Mount Everest right now to believe there are some definite events happening on the slopes of Mount Everest right now. — Apustimelogist

I'm not quite seeing where this relates to the contradiction noted? (response to bold below this all)

If we literally cannot know anything about hte intrinsic nature of things, what you think or believe has precisely zero bearing on the potential question: How could you possible confirm that:

there is an objective way the world is — Apustimelogist

If:

science cannot tell us anything about the fundamental "intrinsic nature" of things beyond experience. — Apustimelogist

These are directly in opposition, as best I can tell. The example you gave doesn't seem to approach the problem in any way... Premeptively, if i've missed something key, apologies.

Response to the bolded: That's true - but to be correct you'd have to solve the above. And given you're making a pretty absolute claim here for science establishing a mind-independent, objective world outthere beyond experience. -

wonderer1

2.4kBut is it? Who are the case studies for that view? I know of a clique of academic philosophers who are customarily associated with pretty hard-edged materialist theories of mind: they are P & P Churchland, a married couple who are both academics, Alex Rosenberg, and the late Daniel Dennett are frequently mentioned in this regard. — Wayfarer

wonderer1

2.4kBut is it? Who are the case studies for that view? I know of a clique of academic philosophers who are customarily associated with pretty hard-edged materialist theories of mind: they are P & P Churchland, a married couple who are both academics, Alex Rosenberg, and the late Daniel Dennett are frequently mentioned in this regard. — Wayfarer

The philosophers who are currently growing up amidst the development of AI, and noticing the relevance of what is going on in AI to the way our minds work, will be the ones to watch. The philosophers you mention above developed their idea during the infancy of neuroscience rather than the explosion of neuroscientific understanding, which will be coming due to the use of AI.

Of course, I don't expect you to be other than analogous to a flat earther when it comes to this subject. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI think its about the idea that there is an objective way the world is and the mind is embedded within that. — Apustimelogist

Wayfarer

26.1kI think its about the idea that there is an objective way the world is and the mind is embedded within that. — Apustimelogist

Further to this point. The idea I keep coming back to is that we instinctively accept that mind is 'the product of' matter. The causal chain which supports this contention is ostensibly that of the neo-darwinian synthesis, which proposes that the brain evolved through the aeons to the point where it is able to generate the mind-states that comprise experience. So, mind as a product of matter - the essential contention of materialist theory of mind.

But what we understand as physical facts are in reality dependent on the mind. That doesn't mean we can generate our own facts gratuitously or casually - I often quote the maxim, 'everyone has a right to their own opinions, but not to their own facts'. And I think that's true. There is a massive and ever-growing body of objective facts. But again, I argue that objective facts are invariably surrounded and supported by an irreducibly subjective or inter-subjective framework of ideas, within which they are meaningful, and one which the empiricist understanding of 'mind-indendent nature' doesn't acknowledge.

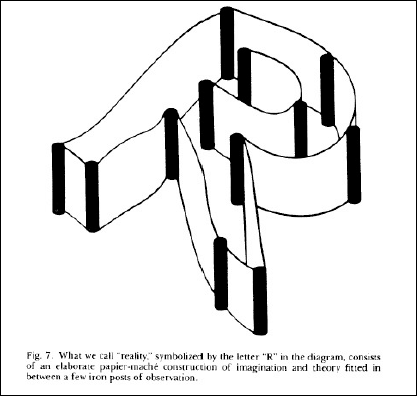

Hence this graphic from physicist John Wheeler:

The caption reads, ‘what we consider to be ‘reality’, symbolised by the letter R in the diagram, consists of an elaborate paper maché construction of imagination and theory fitted between a few iron posts of observation’ (from his paper Law without Law.)

This is also suggested by a paper on a physics experiment known as Wigner's Friend which creates an experimental setup that calls into question that subjects all see different perspectives on the same thing. This experiment shows that two subjects can see different results that are both supposedly 'objectively true'. So it's touted as 'calling objective reality into question' although that needs to be carefully interpreted. It doesn't mean 'anything goes' or that total relativism reigns. As noted, there's indubitably an enormous range of objective facts about which you or I can be right or wrong. But there is also a subjective element which is generally overlooked by 'objectivising' tendencies of today's scientific culture.

Chapter 6 in Hoffman's book deals with a lot of this kind of material.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum