-

Arcane Sandwich

2.2kHere's the thing, Australia doesn't exist according to this fine gentleman:

Arcane Sandwich

2.2kHere's the thing, Australia doesn't exist according to this fine gentleman:

You're living in a fairy tale. -

Wayfarer

26.1kIt is truly a horrible painting. I don't much like Gina Reinhardt, she's Australia's richest women, heir of a massive iron ore fortune, and a Trump toady, trying to create an Australian MAGA party. But as much as I dislike her, I agree that painting is truly awful.

Wayfarer

26.1kIt is truly a horrible painting. I don't much like Gina Reinhardt, she's Australia's richest women, heir of a massive iron ore fortune, and a Trump toady, trying to create an Australian MAGA party. But as much as I dislike her, I agree that painting is truly awful.

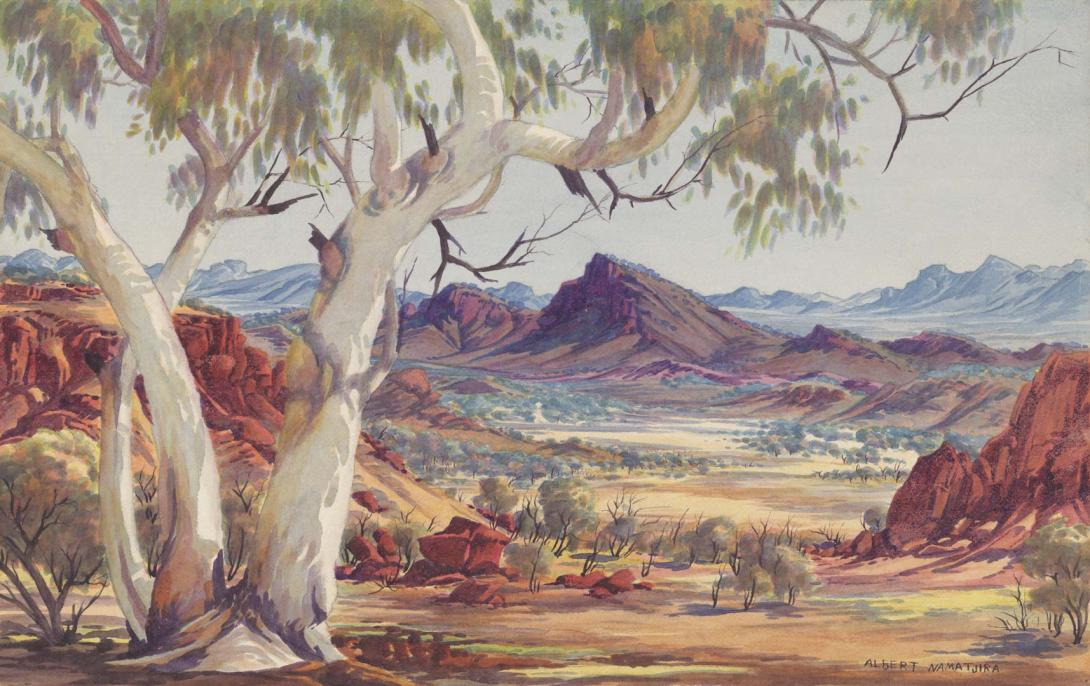

As for the artist - Vincent Namatjira is is great-grandson of another famous indigenous artist, Albert Namatjira (1902-1959). Albert Namatjira was well-known for painting Australian landscapes in a classical European watercolour style, which I would guess is a bit politically uncomfortable for many people today, because anything classical and European is, of course, associated with colonialism and the oppression of First Nation's peoples.

An example of Albert Namatjira's art:

So, reading around, I notice in the Wikipedia entry, that:

Initially thought of as having succumbed to European pictorial idioms – and for that reason, to ideas of European privilege over the land – Namatjira's landscapes have since been re-evaluated as coded expressions on traditional sites and sacred knowledge..

...presumably meaning that his works have been declared to adhere to politically-correct aesthetic standards by the appropriate cultural guardians.

Vincent Namatjira's work, on the other hand, is nowadays popular, but, to me at least, seems to lack the graceful aesthetics, not to mention artistic technique, of his grandfather's.

Source

But each to his or her own, I suppose. -

Arcane Sandwich

2.2kIt is truly a horrible painting. — Wayfarer

Arcane Sandwich

2.2kIt is truly a horrible painting. — Wayfarer

But that was the creative intent of Vincent Namatjira. He made her ugly on purpose. Why? Because she's ethically ugly, she has no moral values.

EDIT: Or think of it like this, Wayfarer: why would he paint her beautifully? As an Aboriginal Australian, he perceives her as an oppressor. Why would he glorify her? -

Arcane Sandwich

2.2kDo you have a horse in this race, mate? According to some Oossians, you need to have an intellectual horse in a philosophical discussion, in order to be able to have that discussion in a respectful way. It's a fallacy, of course, I'd call it "appeal to nonsense", but it already has a technical term in the literature.

Arcane Sandwich

2.2kDo you have a horse in this race, mate? According to some Oossians, you need to have an intellectual horse in a philosophical discussion, in order to be able to have that discussion in a respectful way. It's a fallacy, of course, I'd call it "appeal to nonsense", but it already has a technical term in the literature.

EDIT: I could call it "Appeal to the Boy Scouts" and publish a paper on it. Hmmm... -

Wayfarer

26.1kIt was only by reason of the media flap about that particular painting that I learned anything about the artist. I didn't mean that he should try and beautify or embellish a portrait of Reinhardt, heavens no.

Wayfarer

26.1kIt was only by reason of the media flap about that particular painting that I learned anything about the artist. I didn't mean that he should try and beautify or embellish a portrait of Reinhardt, heavens no. -

Arcane Sandwich

2.2kI do see your point, though. You're arguing that he doesn't seem to know the craft of painting as well as his grandfather did, as in, he doesn't seem to have the same level of technical knowledge. I think that's a fair critique in general, as far as Philosophy of Art goes.

Arcane Sandwich

2.2kI do see your point, though. You're arguing that he doesn't seem to know the craft of painting as well as his grandfather did, as in, he doesn't seem to have the same level of technical knowledge. I think that's a fair critique in general, as far as Philosophy of Art goes.

(edited for erratas) -

Wayfarer

26.1k:up:

Wayfarer

26.1k:up:

When I was a kid, I knew about Albert Namatjira - I think one of my schoolteachers showed us his paintings, and I thought they were beautiful works. Still do, even if they’re kind of old-school. -

kazan

485@Wayfarer &@Arcane Sandwich,

kazan

485@Wayfarer &@Arcane Sandwich,

In the late 1960's Australia, A.N.'s watercolours were highly sought after and regarded as breaking away from the Euro. watercolour styles. ( Note: "breaking away from", not "different to"). They were regarded as sophisticated in comparison to the now highly commercialized but then considered "primitive", "traditional/dot" finger paintings.

How the appreciation of art oscillates powered by sale prices, that is if art gurus/critics/schillers/sprookers even consider the arts in more than a superficial philosophical and psychological manner when commenting on particular art in their 30 second bite on media shows?

The current "Who has copyright?" question regarding Aboriginal art works and the whole question of who can use that "style" is currently going through its legal and legislative process.

But haven't heard of a question being raised about any other "style" only belonging to a specific or specified group of people in Aust.

curious smile -

kazan

485The major parties look like bleeders after the Vic by-elections. Further drift to cross benches in the primary votes. Minority govt federally looking more likely if dissatisfaction in Vic is a nationwide phenomenon?

kazan

485The major parties look like bleeders after the Vic by-elections. Further drift to cross benches in the primary votes. Minority govt federally looking more likely if dissatisfaction in Vic is a nationwide phenomenon?

Wonder how the great Mandates argument with be spun by the main party with less than 30% of the primary vote in a minority govt.? That will be the eleventh great wonder of the world!

And how many minority govt. election cycles, will the country tolerate before a big swing back to a major party, will the coalition handle before the Nats. go it alone?

Just a thought.

usual smile -

Banno

30.6kDid anyone catch the Quarterly Essay Minority Report?

Banno

30.6kDid anyone catch the Quarterly Essay Minority Report?

An extract at https://www.quarterlyessay.com.au/essay/2024/11/minority-report/extract

A podcast interview at https://www.abc.net.au/listen/programs/bigideas/quarterly-essay-george-megalogenis-australian-federal-politics/104880452

The thesis is that the electoral backlash in Australia is unique in that it rejects both major parties at once. That the Liberals have moved too far to the crazy right, while the Labor party is too afeared to do anything. Well argued and data-based.

It will be an interesting election. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI'm one of those of whom it is said 'He doesn't know much about Modern Art, but he knows what he likes'. I like Albert, not so much Vincent. Seems to me Vincent can’t paint any better than I can, but if that was all I could do, then I wouldn’t do it. Which is why I don’t paint.

Wayfarer

26.1kI'm one of those of whom it is said 'He doesn't know much about Modern Art, but he knows what he likes'. I like Albert, not so much Vincent. Seems to me Vincent can’t paint any better than I can, but if that was all I could do, then I wouldn’t do it. Which is why I don’t paint. -

Arcane Sandwich

2.2kWell, but arguably everyone can paint like Piet Mondrian. Arguably, anyone can start a punk rock band, you don't even need to know how to play an instrument. That's another legitimate discussion in Philosophy of Art. It doesn't seem to me to be the case that Vincent needs to have good technique or knowledge of the craft of painting in order to make a powerful statement about Gina, and about other people.

Arcane Sandwich

2.2kWell, but arguably everyone can paint like Piet Mondrian. Arguably, anyone can start a punk rock band, you don't even need to know how to play an instrument. That's another legitimate discussion in Philosophy of Art. It doesn't seem to me to be the case that Vincent needs to have good technique or knowledge of the craft of painting in order to make a powerful statement about Gina, and about other people. -

Arcane Sandwich

2.2kIn fact, I'd argue that one possible slogan is this one:

Arcane Sandwich

2.2kIn fact, I'd argue that one possible slogan is this one:

"Australia: a beautiful land (as seen in Albert's paintings) with ugly people (as seen in Vincent's painting of Gina). -

Arcane Sandwich

2.2kI'll just leave this here:

Arcane Sandwich

2.2kI'll just leave this here:

Indigenous Sovereignty and the Being of the Occupier: Manifesto for a White Australian Philosophy of Origins

CONTENTS

1. Introduction: The Call for a Manifesto

2. The Need for a White Australian Philosophical Historiography

3. The ‘Hypothetical Nation’ as Being Without Sovereignty

4. A Genealogy of the West as the Ontological Project of the Gathering-We

5. Ontological Sovereignty and the Hope of a White Australian Philosophy of Origins

6. The World-Making Significance of Property Ownership in Western Modernity

7. Sovereign Being and the Enactment of Property Ownership

8. The Onto-Pathology of White Australian Subjectivity

9. Racist Epistemologies of a Collective Criminal Will

10. The Perpetual-Foreigner-Within as an Epistemological Construction

11. The Migrant as White-Non-White and White-But-Not-White-Enough

12. Three Images of the Foreigner-Within: Subversive, Compliant, Submissive

13. The Imperative of the Indigenous - White Australian Encounter

References — Toula Nicolacopoulos and George Vassilacopoulos

Indigenous people cannot forget the nature of migrancy and position all non-Indigenous people as migrants and diasporic. Our ontological relationship to land, the ways that country is constitutive of us, and therefore the inalienable nature of our relationship to land, marks a radical, indeed incommensurable, difference between us and the non-Indigenous. This ontological relation to land constitutes a subject position that we do not share, and which cannot be shared, with the postcolonial subject whose sense of belonging in this place is tied to migrancy. — Aileen Moreton-Robinson

----------------------------------------------------------

Source:

Aileen Moreton-Robinson, ‘I Still Call Australia Home: Indigenous Belonging and Place in a White Postcolonising Society’, in Sara Ahmed, Claudia Cataneda, Ann Marie Fortier and Mimi Shellyey (eds.), Uprootings/Regroupings: Questions of Postcoloniality, Home and Place, London and New York, Berg, 2003, pp. 23-40.

A spectre is haunting white Australia, the spectre of Indigenous sovereignty. All the powers of old Australia have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this spectre: politicians and judges, academics and media proprietors, businesspeople and church leaders. — Toula Nicolacopoulos George Vassilacopoulos

True heirs to this tradition of power and self-denial, white Australians are today still refusing to become free. In our two centuries-long refusal to hear the words—‘I come from here. Where do you come from?’—that the sovereign being of the Indigenous peoples poses to us, we have taken the Western occupier’s mentality to a new, possibly ultimate, level. Unable to retreat from the land we have occupied since 1788, and lacking the courage unconditionally to surrender power to the Indigenous peoples, white Australia has become ontologically disturbed. Suffering what we describe as ‘onto-pathology’, white Australia has become dependent upon ‘the perpetual-foreigners-within’, those migrants in relation to whom the so-called ‘old Australians’ assert their imagined difference. For the dominant white Australian, freedom and a sense of belonging do not derive from rightful dwelling in this land but from the affirmation of the power to receive and to manage the perpetual-foreigners-within, that is, the Asians, the Southern European migrants, the Middle Eastern refugees, or the Muslims. In an act of Nietzchean resentment, white Australia has cultivated a slave morality grounded in a negative self-affirmation. Instead of the claim, ‘I come from here. You are not like me, therefore you do not belong’, the dominant white Australian asserts: ‘you do not come from here. I am not like you, therefore I do belong’. Might the depth of this self-denial manifest dramatically, not in any failure to embrace a more positive moral discourse but, in the fact that white Australia has yet to produce a philosophy and a history to address precisely that which is fundamental to its existence, namely our being as occupier? — Toula Nicolacopoulos George Vassilacopoulos

Dead can Dance - Yulunga

Dead Can Dance are an Australian world music and darkwave band from Melbourne. Currently composed of Lisa Gerrard and Brendan Perry, the group formed in 1981. They relocated to London the following year. Australian music historian Ian McFarlane described Dead Can Dance's style as "constructed soundscapes of mesmerising grandeur and solemn beauty; African polyrhythms, Gaelic folk, Gregorian chant, Middle Eastern music, mantras, and art rock. — Wikipedia

The Rainbow Serpent is known by different names by the many different Aboriginal cultures.

Yurlunggur is the name of the "rainbow serpent" according to the Murngin (Yolngu) in north-eastern Arnhemland, also styled Yurlungur, Yulunggur Jurlungur, Julunggur or Julunggul. The Yurlunggur was considered "the great father". — Wikipedia -

Arcane Sandwich

2.2k40 degrees Celsius (104 Farenheit) right now in the small coastal town where I live in Argentina

Arcane Sandwich

2.2k40 degrees Celsius (104 Farenheit) right now in the small coastal town where I live in Argentina

And these stupid Eucalyptus trees that some genius brought from Australia are soaking up all of the moisture from the soil. God damn it. -

kazan

485@Wayfarer,

kazan

485@Wayfarer,

Interested in art (graphic) history. No interest or capability in its creation. Dislike even house painting. A recognized incapacity which needs no excuse.

Like you, enjoy Albert's art, no interest in that item of Vincent's art. But, many BIG art prize entries don't interest either. Personal taste needs no justification unless it comes with social status/responsibility.

Just an opinion/thought.

@Arcane Sandwich,

Was there marsh/swamp/wet lands, that it was "decided" had to be removed, where the Eucalypts were planted in your town?

They were often touted as a "warm" climate swamp drainage/reclamation "devise"...e.g. under Fascist rule, the malaria infested swamps between Roma and Ostia were planted with Eucalypts which led to the first relief from that summer plague since Roma's foundation. As you may be aware.

In the dry parts of much of Australia, a line of healthy gum trees (Eucalypts) in an otherwise low scrub or scarcely grassed dry region, indicates at least seasonally abundant water...usually!

At approx. 3.30 pm, cooler day here. Only 38C. Relative humidity < 20%.. (recording devise bottoms out at 20%.) Overnight minimum was 18C. Quite bearable for this time of year.

cheerful smile -

Arcane Sandwich

2.2kWas there marsh/swamp/wet lands, that it was "decided" had to be removed, where the Eucalypts were planted in your town? — kazan

Arcane Sandwich

2.2kWas there marsh/swamp/wet lands, that it was "decided" had to be removed, where the Eucalypts were planted in your town? — kazan

Nah mate. Just some families that were into the lumberjack business. Their idea was: plant a ton of Eucalyptus, chop em, sell them, repeat. This isn't Australia, these trees are not a native species to Argentina, and they feel no pain. That's the justification here. They are not sacred to the indigenous populations of Argentina. Well, maybe they're sacred in some way to Australian Agentines. Bunch of unpatriotic crooks if you ask me. -

kazan

485@Arcane Sandwich,

kazan

485@Arcane Sandwich,

Sounds like the world over, short term gain ignores long term pain. We're all guilty of it... in someway or other, our descendants will claim and complain.

wry smile -

Arcane Sandwich

2.2kWell I mean, there's Australian Paraguayans. We've been over this, in this Thread. And some (not all) of my Goddam neighbors want to call themselves "Australian Argentines". Like, really? What do I care that your granddaddy or whoever came here from Australia? This isn't Australia, you say so yourself whenever someone criticizes those stupid Eucalyptus trees that your stupid family brought here in the first place. They're drying up the neighborhood, you unpatriotic crook. If you really cared about those Eucalyptus for anything other than lumber-milling, you'd at least know their biological role in the Australian ecosystems.

Arcane Sandwich

2.2kWell I mean, there's Australian Paraguayans. We've been over this, in this Thread. And some (not all) of my Goddam neighbors want to call themselves "Australian Argentines". Like, really? What do I care that your granddaddy or whoever came here from Australia? This isn't Australia, you say so yourself whenever someone criticizes those stupid Eucalyptus trees that your stupid family brought here in the first place. They're drying up the neighborhood, you unpatriotic crook. If you really cared about those Eucalyptus for anything other than lumber-milling, you'd at least know their biological role in the Australian ecosystems.

Phew, sorry, had to vent in order to explain why I'm furious about these trees even being here. -

kazan

485@Arcane Sandwich,

kazan

485@Arcane Sandwich,

You're lucky Gonwanaland, or whatever it's called, broke up, or you may have been lumbered with gum trees as native species. Or not?

chuckle and smile -

Arcane Sandwich

2.2kPangea forms and disperses every now and then. It's done it several times in the past. The craziest thing though is that New Zeland has its own (sunken) continent, called Zealandia if I recall correctly.

Arcane Sandwich

2.2kPangea forms and disperses every now and then. It's done it several times in the past. The craziest thing though is that New Zeland has its own (sunken) continent, called Zealandia if I recall correctly. -

Wayfarer

26.1kWell, maybe they're sacred in some way to Australian Agentines — Arcane Sandwich

Wayfarer

26.1kWell, maybe they're sacred in some way to Australian Agentines — Arcane Sandwich

Yes, but Argentina also has a large beef cattle industry. We have that in common also.

When we visited California, we noticed large swathes of eucalypt, in some parts north of San Francisco, you could swear you were driving on an Australian freeway, were the traffic not going in the opposite direction.

Like you, enjoy Albert's art, no interest in that item of Vincent's art. But, many BIG art prize entries don't interest either. Personal taste needs no justification unless it comes with social status/responsibility. — kazan

Agree. Overall I'm more at home with realist art and impressionism than with modernist and abstract. But visual arts are not a big part of my life.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum