Comments

-

Synonymity, Shannon Entropy, Complexity, and the Library of Babel1. The total number of meaningful messages is less than the total number of possible messages. The proof of this is that the same message can be sent using different codes, such that, once transcribed into meaning by the receiver, it is the same message. For an example, we can imagine whole books of English where every letter is simply shifted one space down, A becomes B, Z becomes A, etc. — Count Timothy von Icarus

This is assuming that there is a strict mapping from code to meaning (a surjection in this case). In reality, of course, the interpretation of a text ("code") is not unambiguous, which is to say that the same code can generate multiple meanings for different receivers (readers) or even for the same receiver. -

Transitivity of causationMy question is: isn't this just a debate about the definition of 'causality'? Does it really matter which definition we accept? Can't we simply decide the definition? — clemogo

And by 'definition of causation' I don't mean the literal dictionary definition or scientific definition. I'm referring to whether or not causation is transitive... can we just decide whether or not it is? Or is it something that needs to be discovered somehow? — clemogo

Your question is odd. Surely, if causality is more than an idle fantasy that we are making up here on the spot, then the question of whether causality is transitive is not independent of what we believe causality to be? -

Gettier Problem.JTB is posited not as a dictionary definition of the word 'knowledge' but as a specialist philosophical definition. Like you though, I am not sure how useful it is for that purpose. Sometimes it seems that it has no other use than for people to argue over it, but perhaps my perception is skewed by these perennial Gettier-type debates on the internet.

-

Gettier Problem.It's better to let go of this constraint and simply use the word knowledge as we tend to do in ordinary life, which usually does not pose much problems in discussion, outside of specific cases like this. — Manuel

The thing is that ordinary use varies, and there is a sense of knowledge that answers the JTB criteria. The truth criterion is justified by locutions such as "I thought I knew that P, but I was wrong" (i.e. I didn't actually know that P). Or "A thinks that she knows that P, but she is mistaken."

But I agree that JTB picks out at best some, but not all ordinary senses of knowledge. -

The dark room problemWell, not quite. We want a theory that rules out things that are contradicted by the evidence. — Banno

The thing is that when you reduce a theory to very general and rough slogans, like "minimizing surprise" or "survival of the fittest," you will readily find both apparent examples and apparent counterexamples, which then prompts complaints that the theory is either contradictory or explains too much, or even both (@Kenosha Kid). The devil is in the details, as you acknowledge. Without getting into those details you can't really say anything one way or another.

I am sympathetic to your attitude towards totalizing theories. But there is a difference between a general unifying idea and a detailed treatment of a subject. Evolutionary biology as a whole is a complex and diverse field, appropriate for its complex and diverse subject. And yet Darwin's basic insight pervades it throughout. I think there is room for more such insights in cognitive science and biology.

By the way, looking Friston's publications, you can see a rather typical pattern where the further he gets from his own field, the wider he casts his net, the more diffuse and light on details and empirical support are his (team's) works, shading into pop-science and philosophy-lite. (There is also an inverse correlation with the number of citations...) Then again, if he got something essentially right, then these kinds of big-picture narratives can be valuable as setting directions for future research and providing an insight into large-scale patterns. -

The dark room problemAgain the point is made that an explanation for everything is an explanation for nothing. — Banno

This - not so much this article, but your complaint that PP/PEM seems to have an explanation for everything - reminds me of a common creationists' complaint about the theory of evolution, which often follows a series of failed challenges to its ability to explain evidence. The fact that a theory can explain all evidence doesn't distinguish between a good theory and a vacuous theory. And there is no way to establish which is the case other than scrutinizing the theory and how it purports to explain evidence. There are no easy shortcuts here to dismissive judgements.

Another thing to note is that there are different ways to respond to a challenge. One is to make a positive argument that the challenge misses its target, e.g. by conducting a decisive test, or by showing that what is alleged to be the case necessarily is not the case. Another is to argue that the challenge may not hit the target. For example, when creationists rhetorically ask "what good is half a wing?" one response is to argue that the equivalent of "half a wing" can be adaptive (maybe not for flying). This second mode of response doesn't provide an additional argument for the theory, but it does forestall the challenge and tasks the challenger (or alternatively the defender) with going deeper and doing more work. This is how we can view Friston's response to the "dark room" challenge in the comment article that you shared. -

The dark room problemPoint being, despite some protestations to the contrary, it is still not clear how this fits in with thermodynamics and information theory. — Banno

You picked a rather peripheral article, a comment. Friston's background is in fMRI and computational neuroscience, and that is the inspiration and the main source of evidence for his free energy model, not so much high-level psychology. These would be a better place to start if anyone is looking for more substance:

A free energy principle for the brain (2006)

The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? (Nature Reviews 2010) -

The dark room problemHere's an article that attempts to provide a summation of the thinking around this problem: Free-energy minimization and the dark-room problem — Banno

When I read that sentence I immediately thought of Friston (who is indeed the lead author). Sean Carroll had a podcast with him, where they touched upon the dark room (non-)problem, among other things. It's pretty complicated stuff (at least for someone with no relevant background) that's hard to grasp without getting into some details of information theory, probability, Markov blankets and all that. People shouldn't jump to conclusions based on a short paraphrase.

It may be worth mentioning that the idea of prediction error (surprise) minimization and predictive processing in general has been kicking around in cognitive science for some time. Other notable people actively working on it are Andy Clark (of The Extended Mind) and Jakob Hohwy. Friston's particular contribution is in bringing the Helmholtz free-energy approach to bear on the problem, and then trying to extend it beyond cognitive science to living systems in general.

The problem is in trying to model all human behaviour according to one general rule when in fact it is an interplay between many physical processes evolved at different times in different environments, some overriding. — Kenosha Kid

Sure, but also keep in mind that there can be multiple subsystems that can be described by that model, of varying complexity and operating concurrently on different timescales. -

A common problem in philosophy: The hidden placeholders of identity as realityI think that is the point. — Philosophim

I still don't get the point. Yes, most people don't have the background to understand a complex scientific theory, and popularizations can be misleading by way of instilling a false sense of comprehension. We probably agree on that. But I don't see a connection from this to the topic that you are trying to develop.

But do we know its out there? All that a dimension is, is a variable. We don't really know what the variable represents in reality, because we can't observe it in reality. The fact that we abstract it out to spatial dimensions is the problem. — Philosophim

What exactly do you see as the problem? Abstract thought? -

A common problem in philosophy: The hidden placeholders of identity as realityFirst, I am a bit puzzled by your choice of the words "identity" and "placeholder": I don't think I've seen them used like this before. From the context, you seem to be referring to models, concepts, representations, abstractions, maps (as in "the map is not the territory"). Is that what you mean?

Second, I am struggling to discern your point here. The most specific example that you give concerning the use of extra dimensions in string theories is poorly chosen, since neither you nor most of the readers understand the background enough to have a reasonable discussion about it. That these dimensions are "not representations of reality or dimensions as we believe them to be" is obviously true in one sense: we the common people are used to thinking about space as three-dimensional (and that only because Descartes' invention has been drilled into us from an early age). But what of it? -

Double Slit Experiment.assigns an objective existence to a mathematical entity (the wavefunction), which is absurd — Cartuna

Do you know of any theory in physics or other sufficiently mathematized science that doesn't do exactly that?

What's left is assigning a physical reality of what the wavefunction describes. — Cartuna

So... MWI then? -

Only nature existsI suggest the categories "biological" and "artificial".

They essentially explain the same differentiation that is commonly understood between "natural" and "unnatural" but they are much more precise in doing so. — Hermeticus

How about "natural rock formation"?

Why is it that some people can't wrap their head around the fact that words can have multiple meanings/uses? Have they ever opened a dictionary? Merriam-Webster gives something like 20 distinct meanings of the word 'natural'. -

Consciousness, Mathematics, Fundamental laws and propertiesIt seems that we can easily observe informational correlates of consciousness (such as integrated information theory), and from there construct mathematical theories to quantify the degree of consciousness within a system. — tom111

I don't know what mathematical models you are referring to, but it seems to me that it is unwarranted to jump to any metaphysical conclusions from the mere fact that some descriptive mathematical models of conscious systems don't give you certain features of consciousness. -

Does the Multiverse violate the second law of thermodynamics?Where did you get that from? 90%? No way. Hooks law doesn't apply to most materials. Even with shear it can't be applied to most materials. Maybe for very small forces, or tiny displacements. Mostly though, a linear algebra just isn't applicable. For a metal spring in the physics class it will do. For an atomic nucleus inside an electron cloud, a Hooke approximation will do. — Cartuna

The 90% figure is rhetorical, but yes, much of engineering mechanics is based on the linear elastic model, with plasticity accounting for most of the rest. Applications of non-linear elasticity, rate-dependence, etc. are much less common.

(Relatively) tiny displacements characterize the operating range of most buildings and machinery, and linear elasticity works well in that range. (Of course, the fact that it is computation-friendly is also a big factor in its popularity.) Forces don't have to be so tiny, since materials like steel and concrete have a high elastic modulus. -

Does the Multiverse violate the second law of thermodynamics?Sure, it's much more useful for more ideal mechanical oscillators like atoms. Not very universal for springs and stuff like Hooke had in mind. — Kenosha Kid

It's very useful for practical stuff though: from ball bearings to bridges to tectonic plates. Take Hooke's law into 3D (with shear) and you get linear elasticity, the backbone of 90% of engineering mechanics from 19th century through the present day. -

CoronavirusSince the vaccines don't prevent transmission of the virus, I'm not sure if they reduce the risk of mutations. — Count Timothy von Icarus

They significantly reduce transmission.

On the one hand, yes, people who have been vaccinated get infected at lower rates. On the other hand, evidence from livestock shows that partial immunizations that reduce the severity of a disease but still allow transmission between the immunized tends to make diseases more lethal. Variants that would otherwise die out due to killing their hosts too quickly are allowed to proliferate. — Count Timothy von Icarus

You have one example from livestock, and it doesn't look like what we are seeing with COVID. This virus has produced more transmissible variants, but there is no evidence so far that it is becoming more lethal. The general trend with infectious diseases is to become less lethal over time: there is no evolutionary advantage for an infection in killing off its vector. -

Does the Multiverse violate the second law of thermodynamics?I don't see how. — Kenosha Kid

I was kidding, of course. But you could trace the ancestry to the Hooke's law from the stress components of the tensor. I am not sure, but that may have been the first example of a constitutive material equation, which evolved into continuum mechanics, and from there it's a hop, skip and a jump to GR :) -

Does the Multiverse violate the second law of thermodynamics?Shouldn't the second law of thermodynamics be called a "habit" instead of a law? It seems to me to speak of a tendency to disorder, not an iron-clad rule. — Manuel

Hey, if Hooke's law gets to be a law, thermodynamics is a cert! — Kenosha Kid

Hey, Einstein field equations are basically a glorified Hooke's law :)

The second law is a statistical law, so yes, it doesn't deliver absolutely certain predictions. It works well with probabilistic epistemology though: its predictions should be treated as rational expectations. Yes, it is possible for all the air in your room to spontaneously bunch up in one corner, but you should not take that possibility seriously, on account of its vanishingly low probability.

Right, you could have it, but obviously we don't have it at the macroscopic level, as entropy is observably increasing. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Well, it has been increasing so far, in our corner of the universe...

However, given many worlds, the almost infinitely improbable universe of non-increasing entropy is one of the (almost?) infinite worlds and actually exists.

Whereas you as an observer in one world could expand the volume of a container of gas all day for a billion years and not see entropy remain static a single time, because the probability is incredibly low. — Count Timothy von Icarus

A thermodynamic anomaly could still happen in our world, for all we know. Thermodynamics describes our expectations of what we are likely to observe, and that is not affected by there being many other worlds, because we are only experiencing one world.

Besides, you shouldn't conflate the many branches of the universal wavefunction with the many microstates of each and every statistical ensemble described by thermodynamics. There is no one-to-one correspondence between them, since they describe very different things. -

Does the Multiverse violate the second law of thermodynamics?If you take this at the quantum level though, and assume the Many Worlds interpretation, there are outcomes where entropy isn't increasing as the universe expands. It seems like you could have a uniform, organized expansion after the Big Bang and thus not have the asymmetry of time. — Count Timothy von Icarus

You can have that without Many Worlds too. I don't see what Many Worlds adds here. Instead of one timeline you have an ensemble of timelines all subject to the same statistics. -

Does the Multiverse violate the second law of thermodynamics?The expansion of the universe roughly means that mass or matter density decreases over time, matter dilutes, spreads, thins out spatially, apart from what gravity holds together. With entropy, the density tends to "even out".

Yet, despite the spatial expansion, the quantum energy density remains constant, or the average micro-chaos, in lack of a better term, per spatial unit does not change.

So, matter dilutes, energy of space itself does not. It's like space isn't "stretching", but rather ehh "growing", in lack of better verbiage. — jorndoe

I am out of my depth here, but as far as I understand, dark energy is what accounts for the expansion of space, which in turn creates more dark energy, and so on. What that does to entropy, beyond the effect of non-equilibrium expansion to which I referred earlier, I cannot say. -

Does the Multiverse violate the second law of thermodynamics?How can something become more disorganized if there is more space? — TheQuestion

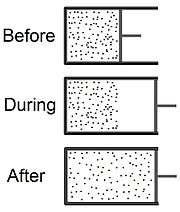

This is why entropy as a measure of disorder isn't always a good metaphor. A textbook example of increasing entropy is a half-evacuated chamber:

When the partition is removed or breached, gas fills the entire chamber. Assuming it does not exchange energy with the environment, the only change here is that the volume occupied by matter increases. Entropy increases because the number of micro-states available to it increases following expansion.

An expanding universe does not require an adjacent empty space to expand into, since space itself expands, but otherwise it presents a similar case. Expansion means more available configurations - means higher maximum entropy at equilibrium - means steeper entropy gradients on the way towards that equilibrium state - means more interesting dissipative structures like stars and living things forming along the way. Yay expansion! -

The biological status of memesWhere I think this gets interesting is in comparisons to Platonism. Plenty of people will accept mathematical Platonism, but reject Platonism in other respects. Numbers exist in their instantiation in the physical world. Memes though, seem to open up the prospect of non-mathematical ideas existing through their instantiation in the physical world as well. — Count Timothy von IcarusSome physicalists would say they are just abstractions, and they can be eliminated from scientific dialogue. Indeed, even the existence of more apparently existing phenomena, for example qualia, have become candidates for elimination. I just don't know if this is correct. How do you ground the social sciences on the physical without looking at the physical instantiation of ideas, which are necessary components of explaining social systems? — Count Timothy von Icarus

How are memes different from other social, or for that matter physical ideas? Contracts, nation states, cats, electrons - these are all instantiations of ideas, in broadly Platonist terms. Non-Platonists will in turn treat memes, assuming they grant them a place in their ontology, as they would other ideas.

The question to be asked about memes is whether they are a well-defined, useful concept, and that has been disputed. Whether they "exist," assuming we give a positive answer to the first question, depends then on your ontological needs and preferences.

Whether memes are alive depends, of course, no the definition of life, which, as you said, is an actively debated question. Coming up with a good definition can be useful for some endeavors, such as origin of life research and exobiology, but the importance of this question shouldn't be exaggerated. In most contexts it matters not at all, and so can be treated as a more-or-less arbitrary convention. -

A single MonismBut who believes that these categories cannot interact? — SophistiCat

The people that proposed them, necessarily.The people that proposed them, necessarily. Or else what does "fundamentally" add to "fundamentally different"? My definition is that it means they cannot interact. — khaled

It is a challenge because it seems clear that incorporeal, immaterial stuff (minds) would have no way to interact with material stuff. It's not a solvable problem, just how long have people been trying to solve it. It's a problem that refutes the position. — khaled

And that's why your construal of the core dualist position cannot be accurate. You've refuted it yourself (your construal). It would be like insisting that the core Christian belief is that Jesus did not rise from the grave, because the alternative is obviously impossible.

Do you have a different definition? — khaled

There are different varieties of dualism and different ways in which its proponents defend it. But the general idea is in singling out the mental as special and central to the conception of the whole world, while preserving a distinction between mental and non-mental. What, if any, position dualists take on the issue of interaction is not what makes them dualists in the first place. Descartes, the poster child of dualism, posited a very real causal interaction between mind and body, but that seemed to be more of an afterthought, when he felt that he had to address the question somehow.

The problem with dualism is that these categories are defined as fundamentally different. — khaled

Yes, but how is that fundamental difference cached out? I don't think there is a single criterion, like causal interaction, on which dualists stake their worldview. And for the same reason, if one views monism simply as a denial of dualism(s), which I think is correct, then there isn't a clear-cut definition of what it is - just a general approach to seeing the world. -

A single MonismExcept it matters how we make these distinctions. To me, positing that there are two fundamentally different kinds of stuff would also mean they cannot interact. Like in the mind body problem.

Monism isn't against making distinctions, it's against making distinctions that make it so that the categories cannot interact. — khaled

But who believes that these categories cannot interact? The mind-body problem is precisely a problem, it is posed as a challenge for dualism, not something that dualism embraces.

I think you are right in framing monism as an opposition to dualism though - that is how it appears historically. Dualism, in its most general outlines, carves out a special and exceptional place for the mental in its ontology and metaphysics. This is sometimes referred to as mentalism. So the best case for monism that I can see is a straightforward rejection of mentalism and nothing more. -

A single MonismYes. That it's ONE fundamental stuff not many. — khaled

I still don't see what substantive claim is being made. Sometimes we make distinctions, sometimes we lump things together. When we lump everything together, we end up with one undifferentiated referrent. Wouldn't that be the same as this fundamental stuff of monism? If so, it doesn't seem to commit us to anything. -

A single MonismNot meaningless. But the debate between the different monisms is. Idealists and physicalists are using different words to talk about the same thing. "Mental thing" adds nothing to "thing" when "mental" is a property of everything. Same with "physical". — khaled

So what does "any one kind of thing" add to just "thing"? What is monism's substantial claim in your view? Is it about the existence of some fundamental "stuff" from which everything is formed? -

Decidability and TruthAs I've said over and over, it's not science, it's metaphysics. It has no truth value. It's something we choose, usually unconsciously. — T Clark

I would say that anything that you are capable of affirming or denying perforce has a truth value, and not just those things that can be scientifically verified. -

Decidability and TruthMy belief, along the lines of Kant's phenomenon and noumenon, is that all understanding we have of complex objects in the world is fictive, whether "unicorns", "tables" or "multiverses". — RussellA

If we can never know whether the multiverse exists or not, even in principle, then we can only know the multiverse as a fictional entity, even if the multiverse does exist as a true fact. — RussellA

You keep going back and forth between calling everything in our experience and imagination fictional (thus rendering the claim vacuous) or specifically those things that we cannot empirically verify (thus merely misusing the word 'fictional'). What's funny is that what you refer to as 'noumenon' is real according to the first criterion (as opposed to the 'phenomenon') and fictive according to the second. -

Decidability and TruthMy belief, along the lines of Kant's phenomenon and noumenon, is that all understanding we have of complex objects in the world is fictive, whether "unicorns", "tables" or "multiverses".

However, even if our understanding of complex objects in the world is fictive, this is independent of the question as to whether such complex objects as unicorns, tables and multiverses actually exist as facts in the world. — RussellA

So it's a completely vacuous statement, but also misleading, since originally you singled out multiverses in particular as fictional. -

Decidability and TruthThis is not intended to be a discussion about what constitutes justification. — T Clark

I understand that, but my point is that you cannot make any progress in answering the question if you are not clear on the criteria that the answer should satisfy. Without that the question is effectively meaningless (as you like to say).

Take interpretations of quantum mechanics, for example:

In my judgement, interpretations that are empirically indistinguishable are the same thing. Differences between them are meaningless — T Clark

Meaningless for you, because of the particular epistemic criteria that you set out for yourself in this case: if you can't put a proposition to an empirical test, then it is meaningless. (Not so for others, so they must be applying different criteria.)

Now, in the OP you want to turn the question onto that epistemic criterion itself. But that's clearly inapt: an epistemic criterion is not the sort of thing that you can test by the methods of science. You can see if it leads to contradictions or to unpalatable conclusions, but that's not the same thing. -

A first cause is logically necessaryAn inadequate argument is a flawed argument. I was a teacher for five years. If you can take a complex concept and break it down so that even a four year old can understand, it is one of the greatest accomplishments you can do. Thank you. — Philosophim

But you didn't explain a complex concept - you gave the sort of use example that would help four-year-olds connect the words "cause" and "effect" with something of which they already have some intuitive grasp. You didn't actually explain anything. Not only is this inadequate to a philosophical discussion of causality, but your repeated appeal to these simplistic examples is patronizing and insulting. -

Decidability and Truthhow do you judge whether a proposition is true or false — SophistiCatJustification — T Clark

Well, that doesn't say much. Justification for whom? Just you, or "us" (as in your response to RussellA), or some kind of objective justification (if that's not an oxymoron)? And what kind of justification?

If it is a matter of what you personally hold to be true or false, decided, undecided or undecidable, then there doesn't seem to be much to puzzle over. Whatever isn't decidedly true or false is perforce neither true nor false. So setting setting that edge case aside, what is it exactly that you are asking?

It is my understanding that all interpretations of QM are equivalent in that they have not been verified and may not be verifiable. — T Clark

Interpretations of QM are equivalent with respect to a particular epistemic standard: that of being empirically distinguishable. But some people prefer one interpretation to another, even while acknowledging that they are empirically indistinguishable. So clearly there can be other epistemic standards at work. -

Decidability and TruthAn example would be helpful if you can think of one. — T Clark

Speaking of epistemic standards, or perhaps just clarifying the question: how do you judge whether a proposition is true or false, decidable or undecidable? Does truth or falsity just mean your opinion on the matter, or do you mean objective truth? By decidable do you mean whether you are able to make up your mind or, again, decidability in some objective sense?

Do you consider any method of evaluation or something more specific, e.g. empirical, scientific test? (When you talk about interpretations of quantum mechanics, for example, it sounds like you mean the latter, to the exclusion of any other standard.)

Any of these questions admit multiple answers, depending on what you want to do. The trick in not getting bogged down in pseudo-paradoxes is being upfront and consistent. -

Decidability and TruthI can't decide whether the question as to whether propositions that are undecidable for us can nonetheless be true or false is itself undecidable or not — Janus

This doesn't seem to lead anywhere, because it involves a vicious epistemic circle. Truth or falsity are established in the framework of some epistemic standards. Janus's statement questions one epistemic standard, which is fine, but the resolution will require some other epistemic standards, distinct from the one that is being questioned. -

What is metaphysics? Yet again.OK, I gather this has nothing to do with peculiarly Greek usage, but with your own views of what words ought to mean, in defiance to the rest of the language users. You are on your own then.

-

What is metaphysics? Yet again.Its not an argument. I describe facts. I came in Greece in an early age. Here they have an obsession with the legacy of their classical Philosophers so from early age we start learning the basics.

I understand that people and time tend to distort words and common usages but that usage is the original, official and only useful, since for almost any other usage we already have words for them. — Nickolasgaspar

Well metaphysics is ANY claim that makes hypotheses beyond our current knowledge.It isn't limited to any specific philosophical distinction. Those are conversations based on metaphysical hypotheses on the differences in the ontology of those phenomena.

-the big bang cosmology before its verification was metaphysics.

-Germ theory was metaphysics and it was assumed a supernatural one (Agents in addition to nature)

-Continental drift theory was metaphysics until we measured the shifting of tectonic plates.

etc. — Nickolasgaspar

I must say, I have never come across this usage. Perhaps it is specific to Greece? (But don't tell me that Greeks own "metaphysics.")

It's funny though that the examples of usage that you give here exactly fit a word that we already have - a word that you use yourself: hypothesis.

SophistiCat

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum