Comments

-

Demonstration of God's Existence I: an Aristotelian proofFeser has a response to exactly this criticism (why does the actualizer have to be purely actual and not simply have unrealized potentials?) on page 66: — darthbarracuda

On that page Feser says, "So, suppose this first actualizer had some potentiality that had to be actualized in order for it to exist." But this misses the criticism. It is already granted that the first actualizer A necessarily exists and so does not have unactualized potential for its own existence. But it may nonetheless have unactualized potential for, say, causing substance S to exist.

If A subsequently does cause S to exist, then it has actualized a potential and thus has changed per premise 2:

- 2. But change is the actualization of a potential.

-

Demonstration of God's Existence I: an Aristotelian proofI will be making several threads in the near(-ish) future about the general proofs of God's existence argued by Edward Feser in his new book, Five Proofs for the Existence of God so we can discuss them and hopefully learn something. First up is his "Aristotelian" proof. — darthbarracuda

The following section of the proof (from Feser's book) is interesting:

- 19. In order for this purely actual actualizer to be capable of change, it would have to have potentials capable of actualization.

- 20. But being purely actual, it lacks any such potentials.

- 21. So, it is immutable or incapable of change.

But why should this actualizer be purely actual and thus immutable? The argument (where A is the initial actualizer and S is a substance being actualized) is:

- 9. A’s own existence at the moment it actualizes S itself presupposes either (a) the concurrent actualization of its own potential for existence or (b) A’s being purely actual.

Feser reasonably argues against (a) and concludes (b):

- 14. So, there is a purely actual actualizer.

But the implication of 9(a) being false is simply that A's existence is necessary for S to be actualized. That doesn't imply the absence of potentials for A and, consequently, doesn't imply A's pure actuality or immutability. And so the subsequent conclusions that assert specific attributes of A (immaterial, omniscient, etc.) don't follow since they require that A be purely actual and immutable.

So the key premise is 9 and it seems to me to be false. -

Demonstration of God's Existence I: an Aristotelian proofThat's not my understanding of Many Worlds. My understanding is that all the possible different worlds already exist, and we are in either a world where it splits or a world where it reflects. We only get to find out which of those worlds we are in after the split or reflection occurs. — andrewk

No (at least, I haven't come across that view).

So, interpreting 'potential' ontologically rather than epistemologically, if we are in the 'split' world there is not only 'potential' but 'inevitability' that the photon will split, and if we are in the 'reflect' world there is no potential that the photon will split - it is inevitable that it will be reflected. That goes against intuition and that is why the epistemological interpretation of 'potential' is more natural. — andrewk

I think you meant "transmit" not "split" above? After the world splits there is a photon on the transmission path and a photon on the reflection path (in different world branches).

Though, given that, I'm not clear on your intuition here. A vase has the potential to break. If it is hit with a hammer, it will break. Similarly, the photon has the potential to split. If it enters a beam splitter, it will split. And each subsequent version of the photon will have the same potential to split.

Doesn't this say that there is a photon prior to it being measured? — Wayfarer

Yes.

That is exactly what is at issue in all of this. Whereas the Aristotelian view that Kasner is talking about seems to be that there is a potential for a photon, which is then actualised by the act of measurement. But up until that measurement, the photon as such doesn't exist, it is only real as 'potentia'. — Wayfarer

Their suggestion seems to be that the potential is real apart from any particulars that would have that potential. Which would make it a Platonic view not an Aristotelian view. -

Demonstration of God's Existence I: an Aristotelian proofLet's take the many-worlds interpretation as an example. In that interpretation, if the universe is in quantum state S at time t, and it would be consistent with the laws of QM for the event E to either occur or not occur at time t+1, there is at least one world which is identical up to t+1 in which E occurs and one in which it does not. So when we say E is 'possible' or 'there is potential for E to occur' all we mean is that we do not currently know whether we are in one of the worlds where E does not occur.

Do you think Feser or Aristotle would be happy to accept that purely epistemological meaning of 'potential'? — andrewk

Aristotelian potential is ontological on the Many-Worlds interpretation.

For a concrete example, consider a photon about to enter a beam splitter. The photon has the potential to be split into two photons by the beam splitter. When the photon enters the beam splitter that potential is actualized. There is subsequently a reflected photon on one world branch and a transmitted photon on the other world branch.

Note that there are no epistemic unknowns here prior to the split. There is no uncertainty about which branch the photon will end up on since there will be a future version of the photon on both branches. -

Is 'information' physical?If you do not allow that the potential for the existence of an object precedes the actual existence of that object, how do you explain becoming? If the potential for a particular hylomorphic substance doesn't precede the actual existence of that substance, how does such a substance come into being from not being? Do all hylomorphic substances have eternal existence? — Metaphysician Undercover

I was referring to the first (primary) hylomorphic particular per the cosmological argument. It can cause subsequent particulars to exist but there are no prior particulars to cause it to exist. Per hylomorphism, only particulars exist and universals are immanent in particulars. So there can be nothing (whether particular or universal) logically prior to the first hylomorphic particular, including time or potentiality. -

Is 'information' physical?The cosmological argument is consistent with what we observe, as well as consistent with logical principles derived from what we observe. Do you recognize that in every case of a hylomorphic particular, the potential for that particular precedes, in time, the actual existence of that particular? — Metaphysician Undercover

No, I don't. Time is a universal. As such, it is immanent in particulars and not transcendent to them.

So, on a hylomorphic version of the cosmological argument, there can be no universals prior to the existence of the prime hylomorphic substance, including time or potentiality. -

Is 'information' physical?Actually, the builder's mind is the cause of the various activities of the builder's body. So ultimately, it is the builder's mind which is the "causal actor" in this case. That is what final cause is all about, and this is understood through the concept of free will. The mind sets into motion physical bodies. But the decisions of the mind, which set these motions, are not caused by any physical motions themselves. So the chain of causes, which we trace back from the existence of the material building, through the hands of the builder, ends with the intentions of the builder, hence "final cause". — Metaphysician Undercover

You've just perfectly described 'ghost in the machine' dualism. I'm suggesting that it is only hylomorphic particulars that have identity. And so existence and causality apply to particulars, not form or matter.

No, this is just a statement of your prejudice. You probably aren't even acquainted with the cosmological argument so you just assert that it must be consistent with what you already believe in order to be coherent. But its coherency is based in principles which you haven't considered yet. — Metaphysician Undercover

I am familiar with how the argument goes. To succeed, the argument must be consistent with what we observe and what we observe are hylomorphic particulars such as the builder, the blueprint and the building, not immaterial forms or formless material.

This really comes down to Wittgenstein's private language argument. Hylomorphic particulars are public observables. Public terms like "form" and "matter" are used to describe those particulars and are not themselves things that have some mysterious ghostly existence or causal efficacy. Only particulars exist and have causal efficacy. -

Is 'information' physical?What implies that form is prior to matter, and therefore has separate existence from matter , is the nature of the particular in relation to the nature of time. That is the cosmological argument. The fact that the mind of the builder, with the form of the building, acts as final cause to create the material building, is referred to to explain this peculiar understanding of reality which is necessitated by that argument. — Metaphysician Undercover

Note that the builder is a hylomorphic substance. It is the builder, not his mind, that is the causal actor. It is he that is constructing the building so that people can live in it (the final cause).

That is the form that the cosmological argument must have if it is to be coherent. It is hylomorphic substances all the way down. -

Is 'information' physical?But then the triadic approach says we can understand the genesis of substantial being by seeking the most generalised image of its particularity. The ontic question becomes what is the most primal incarnation of hylomorphic being? The best answer would be a fluctuation - an action~direction. That is still "a particular something" from one point of view, but it is also the most generalised, or rather the vaguest possible, particular something.

Again, if this seems a weird metaphysical claim, comfort can be found that this is just how modern physical "theories of everything" are having to imagine the creation of the Cosmos. — apokrisis

Agreed and good post. One consequence of continuing to investigate the world is that it ultimately reveals hidden assumptions that force us to look at the world anew (familiar examples being QM and relativity). And this is where philosophy will always have an essential role to play in developing a meaningful and coherent story for those strange hylomorphic creatures that want to know "Why?"

Correction, it is your opinion that this is a false premise of dualism. The Neo-Platonists, following the logical principles which make up Aristotle's cosmological argument, see the need to conclude that the form of the object is prior in time to the material existence of the object; and, it acts as final cause of the object, in the same sense that the blueprints for the building are prior in time to the material building. From this perspective, your claim that the matter and form cannot be ontologically separated has already been proven to be false, and that's why dualism has been so prevalent in the past. It is not the case that modern philosophers have proven dualism to be false, they just totally ignore, and neglect the arguments which prove the need for dualism. — Metaphysician Undercover

Yes, the form of the building can be represented in a prior blueprint. But that doesn't imply that form is separable from matter. Both the blueprint and the building (and also the builder who has the form in mind as the building is constructed) are hylomorphic particulars.

That we can abstractly consider the form of something apart from its matter is the mark of intelligence. But it doesn't imply that form ever is apart from matter (or vice versa). That, to my mind, is the mistake of dualism. -

Is 'information' physical?But that is just a modern atomist/reductionist notion of causality. — apokrisis

No, Democritus' atoms and the void it is not. It's instead the recognition that causality applies to hylomorphic particulars, not to mysterious immaterial forms or formless matter.

Again, I would say the sensible understanding of hylomorphism is triadic. So it is the intersection of formal and material causes that produces the third thing of substantial being.

It is not dualism that is at the heart of things here, but the hierarchical relation of bottom-up constructive actions and top-down limiting constraints. — apokrisis

What is doing the acting? Or constraining? What, on your view, would be an example of a formal cause and a material cause that does not originate in a hylomorphic substance?

And yet Aristotle was concerned with the reality of prime matter and prime movers. — apokrisis

Yes, but that is not hylomorphism, it is remnant Platonism. -

Is 'information' physical?Why wouldn't you say that the particular, the substantial, the entified, is the ultimate resultant? — apokrisis

That's true as well. So we would seek to explain the causes for the chair's existence in terms of other particulars. For example, the person who made it. Or the particles that it is composed of. But it is always the particular that is the locus of cause and effect whatever the mode of causal explanation.

Right. So in what sense is the four legged wooden chair either "primary" or a "constituent"? — apokrisis

In the sense that there is nothing more basic than the particular as an ontological kind. Of course the chair can be composed of further particulars (e.g., the seat and legs, or particles) - that's fine. But the chair can't be ontologically separated into matter and form. That is the false premise of dualism.

So matter and form don't have independent existence. It is only in the unity of substance that they show their reality. Yet hylomorphism is all about how substance is emergent from the intersection of bottom-up construction and top-down constraint - the two varieties of causation in a systems view. — apokrisis

So that unity of substance is ontological of which matter and form are necessary aspects. As to what constructs or constrains a substance, the answer on a hylomorphic view is: other substances. There is no formless matter or immaterial form lurking in the background. -

Is 'information' physical?You yourself talk in terms of ‘top-down causation’. What’s at ‘the top’? It’s not matter - matter is at ‘the bottom’. ‘The top’ is intentional and causative; matter has no causal efficacy of its own. — Wayfarer

I think a problem is the assumption that either matter or form must be the primary constituent. On Aristotle's hylomorphism, neither is. Instead the particular is the primary constituent and matter and form are necessary aspects of the particular. So, for example, the wooden chair has four legs. It is possible to describe just the material of the chair (the wood) or just the form (it has four legs), but it is not possible to separate out either the material or the form from the chair. They are not more basic constituents. They are simply different modes of description.

It is the particular and only the particular that has causal efficacy. Why does the chair hold our weight? Because it is made of solid wood (a material cause) and has four legs (a formal cause). But matter and form are not themselves things that have causal efficacy or have an independent existence. -

Is 'information' physical?The only definition of 'real object' I can think of that isn't a circular definition and that doesn't beg-the-question of the existence of a mind-independent word, and that cannot be doubted by the skeptic, is that a 'real object' is purely a synonym for an object associated with feelings of compulsion. — sime

That Bob is motivated to search for his (alleged) watch implies that he thinks there is a real watch. But that is not what it means for there to be a real watch.

What it means for there to be a real watch is that there is a physical state that would satisfy claims about the watch.

That does presuppose a mind-independent world and can be doubted by the skeptic. -

Is 'information' physical?If ideas exist in brains and brains are physical, then by the same rationale, it is logically impossible to steal other people's ideas: Just as my brain cells are mine and not yours, ideas in my brain are mine and not yours. Yet, there is such a thing as intellectual property, which implies ideas can be stolen. How do physicalists explain this? — Samuel Lacrampe

For a physicalist, an idea is a pattern of physical matter. So stealing (i.e., the illegal copying of) an idea entails the occurence of the same pattern in different physical matter, not the transfer of matter.

But the basic notion I'm working on is that some kinds of ideas are real, and that they constitute the 'archetypes' or forms of existing things. Where I think there is a fundamental error, is to assert that therefore these ideas exist. They don't exist - trees and mountains and rivers exist, and animals and people exist, but the ideas are purely and only intelligible. That's why they're properly described as 'transcendental'; and here a distinction needs to be made between 'what is real' and 'what exists'. I think there's a version of that in Kant's distinction between noumena and phenomena - 'noumena' means really 'the ideal object' which is I'm sure Platonic in origin. — Wayfarer

I agree with this.

And so Aristotle's objection to Plato's Ideal Forms really applies to Kant's noumenon for the same reason. Aristotle agreed that there are ideas and that they are real. But he rejected the view that they are separable from the world of everyday experience. -

Do we behold a mental construct while perceiving?I think part of what makes these questions so confusing and leads to all these two world, two object paradoxes, is that our visual fields really feel like naive realism. It's hard for me to look around myself and not have this distinct sense that my eyes are windows upon an external world, as if I were looking *through* my eyes. — antinatalautist

Yes and that is a misleading idea that should be rejected. Taken literally, it suggests a homunculus (or a ghostly mind) that is looking through the window.

Instead, you are using your eyes and the things that you see are the primitives (or particulars) for higher-level abstractions and explanations. That is, since perception is veridical, that you saw a tree there implies there is a tree there. If, down the track, you find that you made a mistake, then you recategorize the prior experience as non-veridical (i.e., you must have imagined it, you didn't see a tree at all, etc.) -

Do we behold a mental construct while perceiving?I'm going to avoid "direct realism" or "access" because there lies rabbit holes.

For example, when I see a tree while wide awake using my eyes, am I conscious of a mental tree, or the tree itself?

In anticipation of objections concerning seeing mental trees, it's uncontroversial that we experience seeing trees in our dreams, which must be mental, on pain of being a dream content realist. And it's uncontroversial that we can call to waking mind a memory or visualization of a tree, which is also mental. And there's hallucinating a tree.

But is the tree mental when we actually perceive one (see, smell, touch, hear it fall in the woods, etc)? — Marchesk

I think the issue is simply about how veridical and non-veridical experiences are categorized.

When we are awake and in a normal state, we see trees. No problem. Now we can also dream about trees, remember that we saw a tree yesterday, hallucinate a tree, visualize a tree and so on.

However it's a category mistake to suppose that those experiences are a kind of seeing (or perception generally) rather than sui generis experiences. That category mistake leads to the creation of ghostly entities, dualism, skepticism and so on.

So, to answer your question, I think we should apply Occam's razor to the mental trees. -

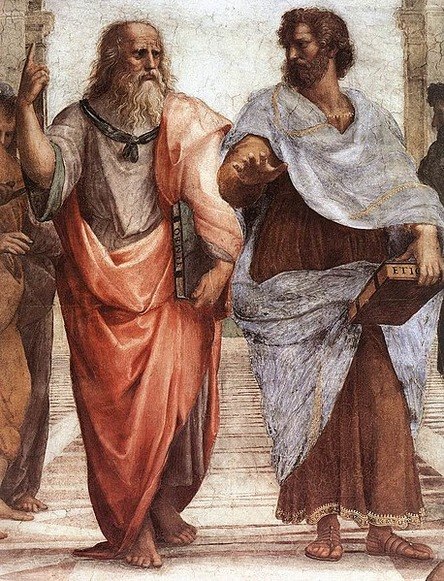

Is 'information' physical?I have an interesting book by Thomas McEvilly, The Shape of Ancient Thought, which is a cross-cultural comparison between ancient Inndian and Greek philosophy. In the introduction, he says that a professor of his once noted that ‘everyone is either a Platonist or an Aristotelian’. — Wayfarer

Yes I think much of the history of philosophy can be seen as the playing out of Platonic and Aristotelian ideas in different contexts.

I would prefer 'instantiated' to 'grounded'. It's more that particulars are 'grounded in form' rather than vice versa. According to A's 'hylomorphic dualism', particulars are always composed of matter (hyle) and form (morphe) - and the form is what is grasped by the intellect, both the intellect (nous) and form (morphe) being immaterial. — Wayfarer

Hylomorphism doesn't imply dualism. The phrase "hylomorphic dualism" seems to have been coined by David Oderberg as a description of the general Thomist view (see Ed Feser's discussion here).

In Aristotle's ontology, the particular is material in a specific form. But there is no ontological separation of form from the particular as there would be under dualism. Instead the particular is described and explained in terms of material and formal causes.

So, for example, it is Alice, a particular human being, who has intellectual capabilities or acts intelligently. But her intellect is not ontologically separate from her matter, just as the ship information is not ontologically separate from the material flag waving and log book ink.

I would say that is the aspect of Aristotelianism which was rejected by the advent of nominalism and then empiricism, as forms and formal causes. — Wayfarer

Agreed, though the main reason was due to the proliferation of unnecessary entities which I think was really a misapplication of Aristotle's basic empirical approach. -

Is 'information' physical?It all hangs on the meaning of the word ‘exists’ (in this case, ‘remains’.) My example of the ship, is indeed a particular instance. But more general forms, such as geometrical and arithmetical forms, might be ‘awaiting discovery’ as it were - any rational being in the Universe would discover such forms. The same could be said in the case of logical laws, such as the law of the excluded middle and so on. — Wayfarer

Yes, we live in an intelligible universe where such laws and forms can be discovered by any rational being.

Say in the case of ‘the idea of the Good’, I would think this is something entirely transcendental, i.e. can’t be represented materially at all. — Wayfarer

Since the common thread for Aristotle is that universals can only be grounded in material particulars, you can probably predict what he thought about Plato's 'idea of the Good':

Aristotle discusses the Forms of Good in critical terms several times in both of his major surviving ethical works, the Eudemian and Nicomachean Ethics. Aristotle argues that Plato’s Form of the Good does not apply to the physical world, for Plato does not assign “goodness” to anything in the existing world. Because Plato’s Form of the Good does not explain events in the physical world, humans have no reason to believe that the Form of the Good exists and the Form of the Good is thereby irrelevant to human ethics. — Wikipedia

I think there’s some merit in what you’re saying, but I do wonder you’re trying to squeeze Aristotle’s ‘moderate realism’ into the Procrustean bed of modern empiricism. — Wayfarer

The way I see it, Aristotle provided some important insights that can inform a modern empiricism, of which his view on universals is one. -

Is 'information' physical?However, even from your summary of the argument, a dualism can be discerned, namely that of an idea and it's representation. In this case, it's a 'ship, 3 masted, Greek, arrives after noon', and the various ways it is represented. I have been attempting to show that this resembles, in some sense, the Platonic meaning of 'an idea', even though the example is a specific idea, and not a general form. — Wayfarer

The Platonic meaning of "idea" is that if you take away the material representations, the eternal idea remains. That is the ghostly existence that Aristotle and Ockham rejected. Instead, the information is only in the material (i.e., flag movements, log book ink) and anyone with the requisite intelligence and skills is able to identify it. -

Is 'information' physical?Nevertheless, the fact of there being 'north' is not dependent on whether there is a city called 'Edinburgh' or not. — Wayfarer

A relation depends on particulars whatever names they may have. For Aristotle, the empirical (or phenomenal) world just is the intelligible world. So you won't find universals prior to or separate from the particulars that they are predicated of.

This is what distinguishes Aristotle's solution to the problem of universals from Plato's. -

Is 'information' physical?4. The 'existing in a ghostly or ethereal domain' is the entire problem and error of the understanding of forms, in a nutshell. This is what almost anyone thinks nowadays, and then rejects the idea on the basis of this poorly-formed understanding. Universals don't exist - that's why they're called 'transcendental', they're logically prior to 'what exists'. But, they're real, in a way that phenomenal objects are not. The 'ghostly domain' that is misleadingly named here, is sometimes referred to as the 'formal realm' - it's not actually 'a realm', but a domain, like 'the domain of natural numbers'. But it's the 'domain of form', namely, that of numbers, possibles, universals, and so on, that in some sense is logically prior to the 'phenomenal realm'. — Wayfarer

Part of the "ghostly existence" problem is the issue of logical priority. I think Russell's example that Edinburgh is north of London shows that the particulars are prior to the universal (the relation in this case).

The "is north of" relation is simply the logical consequence of London and Edinburgh being located where they are in a physical world with poles. Without those particulars, no logical consequence follows and so there is no relation.

As Russell points out the relation obtains independent of language and thought, contra Nominalism. But, contra Platonism, the particulars are prior to that relation. -

Is 'information' physical?↪Andrew M Thanks, very interesting. And I tend to think the ‘immateriality of information’ has tended to show up in physics, also. I don’t know if you noticed the article I linked from this post but it explicitly speaks of quantum physics in terms of the Aristotelian ‘potentia’. — Wayfarer

That's not really what Aristotle meant by potential. What the authors (and Heisenberg before them) are doing is replacing Descartes' res cogitans with res potentia. But res is a Latin phrase meaning an "object or thing; matter". A universal (whether it be mind or potential or color or number) is not a kind of thing. It's an abstraction of things. So res potentia is just a modern variant of the Platonism that Aristotle was rejecting.

The kind of information that physicists are interested in, at least in a quantum context, include which-way particle information and correlation information between entangled particle pairs.

So the Aristotelian approach would be to look for the concrete particulars that that information is an abstraction of. -

Is 'information' physical?Hmmm. I wouldn't modernise him too much, he still believed that everything has a final purpose. But I have to get into this book I've taken out about him. — Wayfarer

Yes and purpose (a universal) is also immanent in the world, not transcendent to it.

It is absurd to suppose that purpose is not present because we do not observe the agent deliberating. Art does not deliberate. If the ship-building art were in the wood, it would produce the same results by nature. If, therefore, purpose is present in art, it is present also in nature. The best illustration is a doctor doctoring himself: nature is like that.

It is plain then that nature is a cause, a cause that operates for a purpose. — Physics by Aristotle - Book II, Part 8

(Incidentally, there is a nice article on Aristotelean philosophy of maths on Aeon, if you haven't seen it: The mathematical world, Jim Franklin.) — Wayfarer

I hadn't - thanks for linking. As the author says:

Because Aristotelian realism insists on the realisability of mathematical properties in the world, it can give a straightforward account of how basic mathematical facts are known: by perception, the same as other simple facts.

Back to your OP, this same principle applies to information. It's not itself a physical thing (since it's a universal) but is realized in physical things and so can be known by perception. Which is why physicists are interested in it. -

Is 'information' physical?Interesting. I wonder why bother persisting with universals at all. Need to read up! — Wayfarer

Without universals we couldn't make statements about particulars (e.g., I have two hands).

For Aristotle, there is only one world - the world of everyday experience - and it includes both particulars and universals.

So twoness is real (in the world) as an abstraction of particulars (e.g., my left hand and my right hand). -

Is 'information' physical?I don't think that's correct. I think his view was that forms could only be known through the form of concrete particulars, or that the universals could only be known in the form in which they took. But he was no nominalist, in fact nominalism wasn't thought of for millennia afterwards. So I don't think you can say that the form depends on the particular, it is surely the reverse - in hylomorphic dualism, things consist of form and matter. But still reading up on this. — Wayfarer

Aristotle's view was that universals are immanent in concrete particulars not transcendent to them (per Plato). So, for example, there is no universal redness apart from concrete particulars such as apples.

Further, that which is one cannot be in many places at the same time, but that which is common is present in many places at the same time; so that clearly no universal exists apart from its individuals. — Metaphysics Book VII Part 16

Aristotle's dispute with Plato here was not about epistemology, i.e., how one could know about universals; it was about ontology, i.e., whether or not universals were independent of particulars. -

Is 'information' physical?No, it doesn't depend on it. Concrete particulars are instances, or instantions, of the principles. They depend on the principle, but the principle doesn't depend on them. — Wayfarer

And that is the Platonic view that Aristotle disputed. Per Aristotle, the abstract principle depends on the concrete particulars.

Were some other planet to form, and life to evolve on it, then they would eventually discover the law of the excluded middle. — Wayfarer

Yes they would, but only because the LEM presents in specific scenarios that they observe.

For example, an alien tosses a coin (or their alien equivalent) multiple times. That a specific coin toss lands either heads or not heads is seen to exhaust all the possible outcomes which, in abstract terms, just is the Law of the Excluded Middle. -

Is 'information' physical?I don't think it's so clear-cut. Let me ask you this - would the 'law of the excluded middle' be the case, even in the absence of anyone capable of grasping it?

I would think the answer is 'yes'. — Wayfarer

Yes. It is also an abstraction that depends on the existence of concrete particulars.

Do you agree?

I am still in the process of studying Aristotle's hylomorphic dualism, which is his major difference with Plato, but I *think* the difference between the two lies in sense in which number (etc) can be said to exist in the absence of any observer. — Wayfarer

Their difference actually has nothing specifically to do with observers or numbers (as I think your more fundamental example above with the LEM demonstrates). Their difference is simply whether abstractions do or don't have a dependency on the concrete. -

Is 'information' physical?My initial argument, which as far as I am concerned hasn't been rebutted, was simply this: an item of information can be encoded in a variety of different media, and/or a variety of different languages, whilst remaining unchanged. The question I posed was, if the physical representation changes, and the information does not, then how can the information be said to be physical? — Wayfarer

There's a presupposition in your question. Does an abstraction (such as information) depend on the existence of concrete particulars?

Aristotle would say "Yes", Plato would say "No".

What do you say? -

Is 'information' physical?Is five immanent in ****** ? — sime

No, not as the quantity of asterixes which is the abstraction I was implying. So only the number six is immanent.

To get to five, a transformation would need to be applied, e.g., by editing your post to remove one of the asterixes. -

Is 'information' physical?The ***** might represent the number five, but only if you tell me that is what it means. And furthermore, only if I can count. — Wayfarer

***** doesn't re-present the number five. The number five is present (immanent) in *****. It doesn't matter if you don't know that it is there or don't know how to count. It also wouldn't matter if there were no sentient beings in existence. The number five is there as a consequence of the asterixes being there. -

Is 'information' physical?A note on Plato's and Aristotle's idea of 'intelligibility':

"in thinking, the intelligible object or form is present in the intellect, and thinking itself is the identification of the intellect with this intelligible. Among other things, this means that you could not think if materialism is true… . Thinking is not something that is, in principle, like sensing or perceiving; this is because thinking is a universalising activity. This is what this means: when you think, you see - mentally see - a form which could not, in principle, be identical with a particular - including a particular neurological element, a circuit, or a state of a circuit, or a synapse, and so on. This is so because the object of thinking is universal, or the mind is operating universally.

….the fact that in thinking, your mind is identical with the form that it thinks, means (for Aristotle and for all Platonists) that since the form 'thought' is detached from matter, 'mind' is immaterial too."

Lloyd Gerson, Platonism vs Naturalism

that point about the distinction between 'the idea', and 'a synaptic state' is related to the point about the distinction between the physical representation and the meaning. — Wayfarer

Yes, as Gerson says, an idea is not identical with particulars (such as synaptic states), it is instead a formal abstraction of particulars, just as the number five is a formal abstraction of these asterixes (*****).

But this is the crucial point - there is no representation occurring here at all. That is what distinguishes Aristotle's view from Plato's. The asterixes don't represent or refer to the number five (as if the number five were something in addition to or independent of the asterixes). Instead, we just see that there are five asterixes. Or, on Gerson's usage, we mentally see the number five that is present in the asterixes. -

Is 'information' physical?One way of putting it is this: numbers don't exist. You will say, of course they do, here's 7, and 5. But they're not numbers, they're symbols. — Wayfarer

You're correct, they're symbols which represent numbers. But how about these asterixes (*****)?

In this case, the number five is present (or immanent) in those asterixes.

That is the Aristotelian immanent view of universals which is in contrast to the Platonic transcendent view. -

Is 'information' physical?other than to say that 'the act of observation' is noetic rather than physical. — Wayfarer

Per Aristotelian realism, it's not either-or. Observation involves a physical process.

However, that is an interesting point about the contrast between the Aristotelean and Platonic attitude; as it happens, I have just borrowed Gerson's Aristotle and Other Platonists, which I hope will have some discussion of these points. — Wayfarer

Should be interesting. The relevant issue here is Aristotle's solution to the problem of universals. -

Is 'information' physical?It seems to me that whilst the representation is physical, the idea that is being transmitted is not physical, because it is totally separable from the physical form that the transmission takes. One could, after all, encode the same information in any number of languages, engrave it in stone, write it with pencil, etc. In each instance, the physical representation might be totally different, both in terms of linguistics and medium; but the information is the same.

How, then, could the information be physical? — Wayfarer

By having a physical presence and not merely a physical representation.

This is the difference between Aristotelian realism (where the abstract is present in the concrete particulars) and Platonic realism (where the physical world is a representation of the forms).

For a physics example, consider the double-slit experiment. If there is information about which slit each photon went through then no interference pattern forms. So information cannot be a purely abstract entity - it has a physical footprint that makes an observable difference. -

Explaining probabilities in quantum mechanicsWhat you are really saying is that our theories ought to be deterministic. — SophistiCat

Yes I think our theories should be deterministic. But, most importantly, our theories should be explanatory which is how I've used "causal" in this thread. I'm unaware of any non-deterministic theory that meets that criterion.

Consider a simple probabilistic theory about dice. This (well-tested) theory says that any given dice roll will have a 1/6 probability of producing any particular number between 1 and 6. But the theory doesn't explain why dice exhibit that behavior, it just asserts it.

That is precisely the situation with the Copenhagen interpretation and any other interpretations that postulate the Born rule probabilities instead of deriving them. They may make the correct predictions but they don't actually explain anything. -

Explaining probabilities in quantum mechanics↪Andrew M in which case, I faill to see the cogency of that example for Deutsch's argument for there being many worlds. — Wayfarer

The demonstration would require a quantum computer with about 300 qubits. Either that is an engineering problem that can one day be solved. Or there is some unknown law of the universe that prevents that possibility. -

Explaining probabilities in quantum mechanicsIt hasn't been done - it's only a theoretical possibility at present (and, no, classical computers couldn't do this). The practical goal right now is to outperform classical computers, so-called quantum supremacy.

-

Explaining probabilities in quantum mechanicsFactoring large numbers requires physical resources (i.e., a computer). If a successful factorization required vastly more physical resources than were available in the visible universe, then where would those resources have come from?

-

Explaining probabilities in quantum mechanics↪Andrew M where are numbers? Any numbers? There might be a vast domain of which the physical universe is simply an aspect, but which is not physical. //edit// Where is 'the realm of possibility'? You might say 'it doesn't exist', but then, there are some things which are in the domain of possibility, and some things which are not. So there are 'real possibilities' - but they don't actually exist anywhere. Which, in the context, is significant, I would have thought.// — Wayfarer

Numbers aren't anywhere. Numbers are an abstraction over things (which is more-or-less the Aristotelian view).

Possibilities are also abstractions. In ordinary use, a real possibility is just one that is more likely to eventuate. -

Explaining probabilities in quantum mechanicsReading through the reader reviews of that title, it seems Deutsch gives pretty short shrift to anyone who doubts the actual reality of parallel universes, which he seems to think is necessary for the concept to actually work. — Wayfarer

Here's the actual challenge Deutsch raises in his book:

Logically, the possibility of complex quantum computations adds nothing to a case that is already unanswerable. But it does add psychological impact. With Shor’s algorithm, the argument has been writ very large. To those who still cling to a single-universe world-view, I issue this challenge: explain how Shor’s algorithm works. I do not merely mean predict that it will work, which is merely a matter of solving a few uncontroversial equations. I mean provide an explanation. When Shor’s algorithm has factorized a number, using 10^500 or so times the computational resources that can be seen to be present, where was the number factorized? There are only about 10^80 atoms in the entire visible universe, an utterly minuscule number compared with 10^500. So if the visible universe were the extent of physical reality, physical reality would not even remotely contain the resources required to factorize such a large number. Who did factorize it, then? How, and where, was the computation performed? — David Deutsch - “The Fabric of Reality”

Andrew M

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum