Comments

-

Ukraine CrisisZelenskyy promised to end Ukraine's protracted conflict with Russia as part of his presidential campaign — Olivier5

How's that going, exactly?

and has attempted to engage in dialogue with Russian president Vladimir Putin. — Olivier5

Was this before or after he called for the no-fly zone that would inaugurate the annihilation of life on Earth?

And Wiki would no doubt forget that Zelensky's popularity was in the dumps before the war, and which has of course subsequently benefitted from the roiling mass of dead Ukrainians. But don't let anything as trivial as local Ukrainian opinion get in the way of your Western fantasies. Similarly, don't let any of this stop you from fellating the altar of state power. -

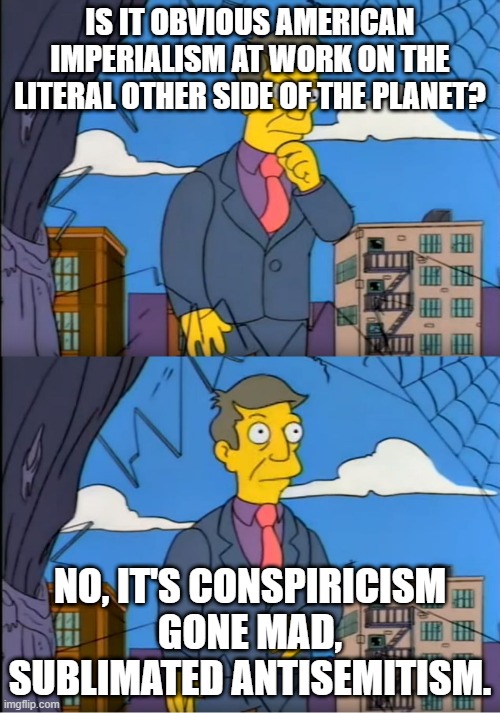

Ukraine Crisis"Despite the fact that the American state literally fucks with every nation on Earth thanks to its enormous and inescapable influence and coercive power, how dare these uppity non-Americans deign to have opinions on the topic. Just like antisemitism."

Imagine being so developmentally stunted that instead of thinking: hold on maybe there's a point to those who are critiquing a country that happens to be intimately involved in fighting a war on the literal other side of the Earth to them, and going - "no, it must be a conspiracy theory".

-

Ukraine Crisis"Gosh imagine people dedicating their time to speak about the most objectively destructive country and economic system on the planet that has objectively contributed to making dead Ukrainians how horrible this is just like antisemitism".

What is pathetic - completely and totally spit-worthy - is the elevation of all inconvenient critiques to the level of 'anti-semitism'. This is what happened to Corbyn's leadership, and it's unsurprising to see it rolled out here. It's using Jewish percecution like a fucking TV trope to be rolled out as one's convince. Fuck that and anyone who weaponizes antiseminism in that way. Oh and I suppose I should name names - @sophisticat. -

Ukraine CrisisSome interesting Ukrainian/Russian(?) anarchist speculations on what comes after:

The worst thing Putin has done in Ukraine is to reconcile the authorities with the people. The president has turned from an object of universal criticism into the Ukrainian Charles de Gaulle. The general of the Ukrainian Interior Ministry offers to deliver himself to the Russian army in exchange for the release of civilians from the besieged city and becomes a national hero. The entire population of Ukraine, from the homeless to the oligarch, unites in a common struggle. It is the same as in the USSR in 1941, when Stalin called everyone “brothers and sisters” and people believed in his sincerity. If that war was a domestic war for the USSR, then this became a domestic war for Ukraine. Kharkov and Mariupol are perceived as Stalingrad, Leningrad or the Brest Fortress.

...Ukraine has always been good at one thing: it was always normal to depose the ruler who displeased the people. This made it different from Muscovy (ancient Russia), where the figure of the Tsar was sacred. The exceptions were the Time of Troubles, which was ended by the merchant (Minin) and the prince (Pozharsky). But in Ukraine, it has always been the rule that unpopular leaders are forced out. This Ukrainian tradition goes back at least to the Cossack times. How many Ukrainian Cossack atamans have paid with their positions, and sometimes with their lives, for “unpopular measures”! Whether this tradition will continue now is hard to say.

[In Russia,] It should be added that if in the wild 1990s, the Russian businessmen were saved from a new popular revolution by gangster strife, which killed off a significant part of the active population (and not the worst part, because in such strife, the first ones to die were the ones who retained a vestige of their humanity, whereas the worst scoundrels survived), now that part same of population will be ground up in the war (and in similar strife after it, when the soldiers who are accustomed to robbing and killing will return from the front). In short, unless some “black swan” flies to the aid of the Russian people, Russia will repeat the Yeltsin-Putin three decades, after which the country will most likely perish [sic], except for Moscow and a few other regions, where there will be established a “thriving economy” with a 12-hour workday for the common people and elite restaurants and brothels for the oligarchs.

https://crimethinc.com/2022/04/06/and-after-the-war-the-prospects-for-social-struggles-in-ukraine-belarus-and-russia

Always nice to be reminded about being infinitely critical of state power, unlike Western liberals who, having learnt the name 'Zelensky' in the last two months having never heard the name before in their lives, have turned him into a new Bono to fangirl over. -

Ukraine CrisisImagine shilling for state-sponsored professional murderers and telling me my psyche is a wasteland.

-

Ukraine CrisisThey are soldiers who killed your friends and family, or - and this much is guaranteed - supported those killings. I'm not saying they should be killed. It'd probably be better if they weren't. I'm just not saying I care about anyone who thinks they should be, and acts on it.

Every solider who comes home in a coffin wrapped in a flag from some kind of overseas adventure is someone's else cause of rightful celebration. One country in particular likes those decorated boxes. -

Ukraine CrisisAnd you're still dull as rocks but that's OK.

But really who cares about Ukrainians killing Russians. If you're going to invade another country, expect to die. You signed up for it, literally. -

Ukraine CrisisTrue. It would be better for all the soldiers to murder their commanding officers instead, on all sides, all the way up the chain. The war would end tomorrow.

Thanks for reminding me about class consciousness, comrade. -

Ukraine CrisisI have zero moral judgement about Ukrainians murdering, in whatever way they see fit, Russian aggressors.

-

Ukraine CrisisBrutal state oppression from authoritarian police regime:

But I'm sure the American bootlickers can tell us all about the free speech of the West they like to slobber on about.

And of course it's quite easy to dissociate oneself from the American far right. Fuck America and everything that piece of shit country stands for. Ta da. Oh yes, and it's puppet institutions like NATO too. -

Ukraine CrisisThe US wants to persecute Putin at the ICC. What, the same body they threaten every time they dare raise the prospect of investigating American war crimes? The same one whose statutes they have not ratified? Fucking joke.

Oh, and the US calling for Russia to be kicked off the UN Human Rights council. My God. A comedian couldn't write better lines if they tried. -

Whenever You Rely On Somebody ElsePolitics is not ethics recast this is the most pernicious idea in all of philosophy and one day we will burn all of Rawls to the ground and everything will be better again.

But otherwise yes absolutely, the ability to rely on, and work with each other has amplified human ability beyond anything any of us could ever imagine. -

Ukraine CrisisThe EU resents being dependent for resources, doubly so because they are dirty resources that pollute the environment, and so it projects these negative feelings onto the country from which it imports those resources. — baker

As much as I would like to believe this I would not frame things in these terms. For one, it assumes the EU gives a damn about trading with tyrants. As if it has never willingly accepted blood money without question. Second, never account in terms of feelings what can be accounted for in terms of power. And this is very much about power. -

Ukraine CrisisSome interesting debates in good left spaces about the best way to respond to events in Ukraine:

Alex Callinicos - The Great Power Grab: https://socialistworker.co.uk/features/the-great-power-grab-imperialism-and-war-in-ukraine/

Gilbert Achar - Six FAQs on Anti-Imperialism Today and the War in Ukraine: https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article7571

Gilbert Achar - A Memorandum on the radical anti-imperialist position regarding the war in Ukraine: https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article7540

Alex Callinicos and Gilbert Achar Debate - Ukraine and Anti-Imperialism: https://socialistworker.co.uk/long-reads/ukraine-and-anti-imperialism-gilbert-achcar-and-alex-callinicos-debate/

Stathis Kouvelakis - The war in Ukraine and anti-imperialism today: a reply to Gilbert Achcar: http://isj.org.uk/anti-imperialism-a-reply-to-achcar/

Kouvelakis is convincing even if cold:

"It is absurd to claim, as Western governments and the media never cease to do, that Putin is nothing other than a paranoid, “mentally disturbed” man who imagines being “encircled” by hostile powers. No, unfortunately this is not a fantasy, and was being put in place well before Putin, when Russia was completely bled out and on her knees before the West. Let’s also not forget that Putin came to power by positioning himself initially as a strict continuation of Yeltsin and his pro-western policies. This attitude of the Western bloc isn’t the result of an ideological blunder or a disembodied desire for power, but the outcome of its imperialist nature. In order to perpetuate itself, the West needs enemies. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, it never accepted the idea of inviting the new Russian capitalist class to the table, because the idea of Russia as an eternal “Other” and a potential threat always prevailed. It also has to be underlined that the elites from the countries of the former Soviet bloc, or of the Soviet Union itself (including the Ukrainians, particularly after 2014), played this card to the utmost in order to consolidate the power of the new layers of oligarchic capitalists and legitimise their position with peoples who wanted revenge on the former custodial power.

One can’t play the game of scorned innocence and claim that the expansion of NATO was only a pretext or diversion invented by Putin, while, for years, the US and her allies have launched themselves into escalating the pressure and encirclement of Russia, considered more and more explicitly as a systemic enemy—while there is hardly any divergence in socio-economic terms with the West...

...Zelensky is certainly not the “Nazi” talked about by Putin, but he isn’t Ho Chi Minh either… The Ukrainian government is a bourgeois government, that serves the class interest of capitalist oligarchs, comparable in every way with those in Russia and other republics of the former Soviet Union, and which intends to align the country with the Western camp, without any concern for the predictable consequences. In her masterful 2018 study, Ukrainian critical economist Yuliya Yurchenko aptly analysed this regime as a “neoliberal kleptocracy”. At the same time as being the victim of an inadmissible aggression, Zelensky’s administration doesn’t represent any progressive cause, and it would be totally absurd for left-wing forces worthy of the name to plead the case of arms delivery. ...

This constant duplicity makes the sanctions put in place by the West for decades, indefensible; their capacity to impose them, serves moreover to confirm Western economic supremacy, China and Russia being only marginal at the origin of these kind of measures (3 percent in 2020). The task of the left is to denounce the political function of this mode of action and to show that it is, above all, a means of strangling a country ruffling the world order fashioned by US and Western domination, a measure that indeed differs little from an act of war. ...It is only by following this perspective that we can:

- Affirm an autonomous position of condemnation of Russian aggression whilst resisting the surging bellicosity of our governments;

- Preserve the possibility of a truly independent Ukraine and of an enduring peace in Europe;

- Convince the progressive forces in the Global South that, although their hatred of US imperialism and Western arrogance is absolutely justified, goodwill towards Putin isn’t;

- Re-establish an internationalism capable of confronting and defeating the forces of destruction and death that are arising from a world in the grip of capital.

- Affirm an autonomous position of condemnation of Russian aggression whilst resisting the surging bellicosity of our governments;

-

Ukraine CrisisAs it is, I know enough about Russia to know that, as I already said, this campaign is utterly unjustified and unwarranted, and that it is a crime against humanity. And I remain hopeful that the campaign will collapse and the Putin regime along with it. — Wayfarer

"A nuclear power is waging war in another country. I don't need to know what they have to say at all, or consider motivation or interest. This is a very intelligent way to approach world events. I really care about Ukranians".

It must be so nice to be so comfortable in the warm glow of one's own moral recritute that ignorance becomes a virtue. Like having peed in a pool. -

Ukraine CrisisTo be fair I don't think many of those who repeat the 'return to the USSR' line mean much by it other than a certain kind of ~vibe~, something vaguely meaning 'powerful bad guy with grey brutalist architecture and red hammer and sickle flags also very repressive'. As an explanation of Putin's actions that is concerned solely with ideology and vague psychological desires, it just so happens to have the advantage of ignoring, totally, any need for analyzing politics, economics, history or society at large. It plays the role of comforting Western minds even while fulfilling its alarmist duty. The 'actual' USSR is more or less irrelevant. The 'return to the USSR' people sure as hell don't mean collectivization, the liquidation of the Kulaks, rapid industrialization and 5 year plans, or the support for the internationalization of communism abroad.

-

Ukraine CrisisI also see exactly zero reason to applaud someone who purposefully states he's only here to share his opinion and not actual analysis and debate. — Benkei

:up:

"I'm just here to express my moral indignation and repeat verbatim the lines fed to me by most Western media"

"That is right take!" -

Ukraine CrisisMy Dear Russian Friends, It’s Time For Your Maidan by Jonathan Littell ... It wasn’t always like this. There was a time in the 1990s when you had freedom and democracy, chaotic, even bloody, but very real. But 1991 ended the same way as 1917. Why, every time you finally make your revolution, you get so scared of the Time of Troubles that you go and hide under the petticoats of a tsar, a Stalin or Putin? — Olivier5

I still cannot get over how completely, totally, utterly garbage this fucking 'letter' is. Like it still makes me annoyed just thinking about it. So, the celebrated 'freedom' of Russians in the 90's, let's take a look at that:

"Start with real GDP. The decline in Russia was 40%. This is significantly more than the decline in the US or Germany during the Great Depression. Note also that Russian depression lasted longer. ... How does that depression compare w/the past Russia's catastrophes? It was not as bad as the disaster wrought by WW1, Civil War. The industrial output in the latter case dropped to 18% of its pre-war level; in the 1990s, Russia lost "only" half of its industrial output. ... What happened to real wages? They were cut to 1/2 of their 1987 level: much worse than what happened in Poland in the 1990s, and much, much worse than in the US & Germany during the Great Depression (real wages in these two cases went up).

... Ok, we now know: Russia's real incomes were cut by 40% and its inequality skyrocketed. If you are in the lower part of income distribution, you lose not only 40% of your income (the average), but more: perhaps 60-70% as inequality change moves against you. So poverty went "wild"! ... The number of people in poverty in Russia (measured by using the same poverty line of 4 international dollars) went from 2.2 million people in 1987-88 to 66 million in 1993-95; from negligible to more than 40% of the population.

https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1506776903960649735.html

Or maybe this Littell fuck is sincere - it really is just better for the West when Russians are swamped in poverty. -

Ukraine CrisisThe west obviously doesn't have squeaky-clean hands in most of this, but to pretend that Putin is just an unfortunate defender of Russia... — ProbablyTrue

I appreciate that you lack basic literacy skills but you did not have to announce it so loudly to the world.

Are we supposed to take seriously a journalist who takes Putin's stated motivations at face value when the Kremlin has been calling white black and up down for years? — ProbablyTrue

Ah yes the 'ol "secretly aspiring for communism while literally announcing that one is going to kill communists" approach. Putin, that wily fox.

That said I really do genuinely appreciate the acknowledgement that this is, in fact, as you said, a proxy war, and by extension the fact that the US is, in fact, using dead Ukrainians to achieve their geopolitical ends. At least it's honest. -

Ukraine CrisisYou don't even need to cite Syria. The monstrous piece of shit that is Hillary Clinton already suggested it in the context of this war: https://twitter.com/MSNBC/status/1500531727957172224?s=20&t=a574O6MNhzCX_ns1P9-cqQ

---

Also, I loved this piece that makes the point that the selective hysterics over Russia is basically identity politics on steroids:

"On the one hand, we hear from the Wall Street Journal that Russia under Putin is returning to its ‘Asian past’, even though its methods of urban assault are comparable to those deployed by the United States and its allies in Fallujah and Tal Afar. And, similarly, from Joe Biden and neoconservatives like Niall Ferguson that Putin is trying to restore the Soviet Union, even though he declares ‘decommunization’ to be among his aims in Ukraine. Though most politicians and journalists would be too sensible to make this logic overt, hysteria about all things Russian entered warp speed on day one of the invasion

On the other hand, the Ukrainian leadership is conveniently airbrushed and lionised, so that it can be identified as an outpost of an idealised ‘Europe’. Daniel Hannan, writing in the Telegraph, declared: ‘They seem so like us. That is what makes it so shocking.’ Charlie D’Agata of CBS, reporting from Ukraine’s capital, was struck by the same cognitive dissonance: ‘This isn’t a place, with all due respect, like Iraq or Afghanistan that has seen conflict raging for decades. This is a relatively civilized, relatively European city.’ ...This provincializes sympathy with Ukrainians under siege, reducing what might have become a dangerously universalist impulse – raising standards that could apply in Palestine or Cameroon – to narcissistic solidarity with ‘people like us’.

...The culture war over Russia and Ukraine is more about the moral rearmament of ‘the West’ after Iraq and Afghanistan under the ensign of a new Cold War which declares Putin a legatee of Stalin, the resuscitation of a dying Atlanticism, the revitalisation of a moralistic Europeanism after the collapse of the Remain cause, and the stigmatisation of the left after the shock of Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party, than it is about Russia or Ukraine. More broadly, it revives in a new landscape the apocalyptic civilizational identities that were such a motivating force during the ‘war on terror’, and which have lately fallen into disarray."

https://newleftreview.org/sidecar/posts/the-belligerati -

Joe Biden (+General Biden/Harris Administration)Oh the question was facetious. The answer is because Trump supporters are walking slime molds with about as many neural connections.

-

Ukraine Crisis

--

Also imagine thinking voting means anyone in the West lives in anything remotely like a democracy. I mean bloody hell, at least Russians know they live under the thumb of an autocrat murderer - meanwhile, over in moral-rectitude-land, people really think, with a straight face, that they are self-governing in any way, shape, or form. -

Ukraine Crisis"In the US view, this is not a short-term adjustment to regroup, but a longer-term move as Russia comes to grips with failure to advance in the north. The official said one consequence the US is concerned about is keeping the European allies unified on economic pressure and military support as Washington expects some of them to press Ukraine to accept a peace deal to end the fighting. Secretary of State Antony Blinken on Tuesday cautioned that Russia saying it would be reducing hostilities around Kyiv could be "a means by which Russia once again is trying to deflect and deceive people into thinking it's not doing what it is doing."

https://edition.cnn.com/2022/03/29/politics/us-intelligence-russia-ukraine-kyiv-strategy/index.html

An American horror story: that a peace deal is reached and there is no more war.

I don't know how this could be made any more clear: America wants dead Ukrainians, all the better to secure unipolarity. -

Ukraine CrisisMy Dear Russian Friends, It’s Time For Your Maidan

Jonathan Littell — Olivier5

With a straight face - this entire thing was the worst piece of trash I have read since the invasion started. Imagine some Anglo piece of shit in his armchair somewhere telling you that you're not doing enough to resist a regime like Putin's. He has the temerity to wax poetic about 90s Russia when one of the most popular slogans among the Russians remains "the nineties: never again". And then he uses Maidan - a Western supported coup that took place in a basket-case nation with a barely-there state apparatus - to tut tut about ordinary Russians being unable to do the same. And throughout all this he says nothing, literally not a word, about Western support for Putin that not only helped put him into power, but has kept him there so long as the oil has flowed nicely and right up until the point he started getting too uppity on the borders. And what - does he think ordinary Russians don't know the things he writes about? The sham elections and corruption and so on? Like he's imparting some kind of news to them they they don't directly live, day to day? Oh he does end up acknowledging that they do know it, only to use that to further condescend to them from the high-horse he's strapped to. Not to mention the little nod to Navalny, a xenophobic piece of trash who is far more popular in the West than he ever has been among his homeland.

That's not a 'letter to Russian friends'. That's a letter to Westerners in order to make them feel morally superior under the guise of writing to 'Russian friends'. The patronising arrogance it exudes is noxious to high heaven. How anyone can read that without scrunching up one's face is beyond me. As the kids say, it's fucking cringe. That imperious, faux-humble tone throughout - it makes one want to throw up. This kind of 'letter' is what happens when you give a liberal with zero sense of class consciousness a pen and paper.

Can one imagine some Chinese or Iranian writer penning something similar about the West?: "oh my friends, yes, your leaders have committed mass genocide literally anywhere on Earth they have ever stepped foot, but why oh why won't you do something about it?". It's be written off as a laughable piece of wank meant only to impress some Chinese or Iranian leadership bigwigs. God, I've read so much utter, complete fuckwittery about this whole conflict since its started but this one takes the cake. Congratulations on finding the worst possible piece of English prose on Russia to have yet been vomited out into the world. -

Joe Biden (+General Biden/Harris Administration)Biden's budget proposal: 10% increase in military; 11% increase in federal law enforcement; 13% increase for ICE. Biden wants $8.1 billion for ICE, which is higher than the highest amount Trump ever spent on ICE.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/28/us/politics/biden-budget-politics.html

Again, how it is that Trump supporters are not avid fans for Biden is beyond me. -

Ukraine CrisisZizek's invocation of the 'post-modern father' comes to mind:

Instead of bringing freedom, the fall of the oppressive authority thus gives rise to new and more severe prohibitions. How are we to account for this paradox? Think of the situation known to most of us from our youth: the unfortunate child who, on Sunday afternoon, has to visit his grandmother instead of being allowed to play with friends. The old-fashioned authoritarian father’s message to the reluctant boy would have been: “I don’t care how you feel. Just do your duty, go to grandmother and behave there properly!” In this case, the child’s predicament is not bad at all: although forced to do something he clearly doesn’t want to, he will retain his inner freedom and the ability to (later) rebel against the paternal authority.

Much more tricky would have been the message of a “postmodern” non-authoritarian father: “You know how much your grandmother loves you! But, nonetheless, I do not want to force you to visit her – go there only if you really want to!” Every child who is not stupid (and as a rule they are definitely not stupid) will immediately recognize the trap of this permissive attitude: beneath the appearance of a free choice there is an even more oppressive demand than the one formulated by the traditional authoritarian father, namely an implicit injunction not only to visit the grandmother, but to do it voluntarily, out of the child’s own free will. Such a false free choice is the obscene superego injunction: it deprives the child even of his inner freedom, ordering him not only what to do, but what to want to do.

Western propaganda is of the latter type. -

Ukraine CrisisMeanwhile when mass child murderers like Madeleine Albright drop dead, people in the West really are sad about it.

-

Ukraine CrisisOne thing I find disturbing about this whole discussion about propaganda is the inherent racism. — Isaac

Disturbing but not surprising. -

Ukraine CrisisHey look it's that one time from the NYT in 2015 when Obama decided that unlike in other situations he would not continue to be a war criminal!:

I knew that Putin-loving shmuck was up to no good when he decided that er, not provoking Russia was something a sane person would do.

https://nytimes.com/2015/06/12/world/europe/defying-obama-many-in-congress-press-to-arm-ukraine.html -

Ukraine CrisisThe wonderful thing about Western propagandists is that it's propagandists really believe the shit they say. And it's all the more pernicious - along a certain axis - precisely because of that sincerity.

I wish more than anything that our propaganda looked like this:

http://www.china-embassy.org/eng/zgyw/202112/t20211204_10462468.htm

It would be, at least, clear to everyone what is going on.

I think it was Chomsky that had an anecdote somewhere where some bewildered newsroom monkey asked him if Chomsky really believed that he, the newscaster, was just peddling lines fed to him by a higher authority. And Chomsky responded, no of course not - it's much worse. You actually believe the things you're saying. But you wouldn't be in your position otherwise. That's how Western propaganda works. You don't get thrown into jail because you never even remotely get close to the position where any such measures would ever be necessary. The institutional power needed to be able to filter out such viewpoints so early on is more mind-boggling than any torture apparatus, which, frankly, signifies a weakness of the state power. -

Ukraine CrisisGod, just read Perry Anderson's 2015 NLR essay on Russia and it is the best 'take' of all the millions of post-invasion word spew out there. Some highlights:

On Western hypocrisy:

[A] Russian-supplied missile in the hands of the irregulars had shot down a civilian airliner flying over the conflict zone. Denouncing this ‘unspeakable outrage’, Obama called the West to joint action against Russia. Economic sanctions targeting its financial and defence sectors were intensified. That the United States had itself shot down a civilian airliner, with a virtually identical toll of deaths, without ever so much as apologizing for a virtually identical blunder, was naturally in a different sense unspeakable—the airline was Iranian, the captain of the Vincennes acted in good faith, so why should anyone in the ‘international community’ remember, let alone mention it? So too was the annexation of the Crimea unheard of: why should anyone have heard of the seizures of East Jerusalem, North Cyprus, Western Sahara, or East Timor, conducted without reproof by friendly governments fêted in Washington? What matter if in all these cases, annexation crushed the self-determination of the inhabitants in blood, rather than reflecting it without loss of life? Such considerations are beside the point, as if the power that administers international law could be subject to it.

—

On Russian-Western cooperation in the 2000s, something everyone seems to have forgotten:

A glance at Security Council resolutions of the period is enough to see that Russia fell in with the wishes of the West virtually across the board, with the solitary exception of the Annan Plan to dismantle the Republic of Cyprus for a deal with Turkey, which it vetoed on an appeal for help from the government in Nicosia. All told, Russia was more than a reliable and collegial force within the international community. It was the bearer of ‘a civilizing mission on the Eurasian continent’. Under Medvedev, Russian foreign policy bent even further to the West. In compliance with Washington, Moscow cancelled delivery of S-300 missile systems to Tehran that would have complicated Israeli or us air-strikes against the country; voted time and again in the un for sanctions against Iran required by the us; gave a green light to Western bombardment of Libya; and even supplied a transport hub on Russian soil at Ulyanovsk for nato operations in Afghanistan.

—

On the contraditions of the Putin's regime in general:

Putin’s belief that he could build a Russian capitalism structurally interconnected with that of the West, but operationally independent of it—a predator among predators, yet a predator capable of defying them—was always an ingenuous delusion. By throwing Russia open to Western capital markets, as his neo-liberal economic team wished, in the hope of benefiting from and ultimately competing with them, he could not escape making it a prisoner of a system vastly more powerful than his own, at whose mercy it would be if it ever came to a conflict. In 2008–09 the Wall Street crash had already shown Russian vulnerability to fluctuations of Western credit, and the political implications. Once deprived of its current account surplus, a local banker commented with satisfaction, ‘foreign investors will get a vote on how Russia is run. That is an encouraging sign’—putting pressure on Putin for privatization. Such was the objective logic of economic imbrication even before the Maidan.

...Putin’s regime has attempted to straddle the difference between the old order and the new: seeking at once to refurbish assets and orientations that have depreciated but not lost all currency and, heedless of the hegemon, to embrace the markets that have downgraded them—running with the hare of a military cameralism and hunting with the hounds of a financial capitalism. The pursuit is a contradiction. But it is also a reflection of the strange, incommensurate position of Russia in the present international order, in which the regime is trapped with no exit in sight.

—

On American arrogance:

Yeltsin’s Foreign Minister Kozyrev dumbfounded a visiting Nixon by telling him that Moscow had no interests that were not those of the West. With interlocutors like these, representing a government dependent for its continuation in power on economic and ideological support from the West, America could treat Russia with little more ceremony than if it were, after all, an occupied country. When even Kozyrev baulked on being told that it was Moscow’s duty to join Washington in threatening to attack Serbia, Victoria Nuland—currently Assistant Secretary of State for Europe—remarked: ‘That’s what happens when you try to get the Russians to eat their spinach. The more you tell them it’s good for them, the more they gag.’ Her superior at the time, Clinton’s friend and familiar Strobe Talbott, proudly records that ‘administering the spinach treatment’ to Russia was one of the principal activities of his time in office. In due course Obama would say, in public, that Putin reminded him of a ‘sulky teenager in the back of the classroom’. In the ongoing Ukrainian crisis, Nuland could be heard conferring with the us Ambassador in Kiev on the composition of the country’s government in a style compared by an American observer to a British resident issuing instructions to one of the princely states of colonial India. In condescension or contempt, the underlying American attitude speaks for itself: vae victis.

https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii94/articles/perry-anderson-incommensurate-russia -

Ukraine CrisisThe question of how successful or not the invasion is from a Russian standpoint is not equivalent to the question of how many Ukrainian lives are lost. These are two different questions. — Olivier5

My point exactly. But of course, my other point of course is that I don't think people like you give a shit about the latter question.

Streetlight

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum