Comments

-

Quantifier Variance, Ontological Pluralism, and Other Fun StuffI had in mind his Three Worlds conception, — J

Oh, Ok. "world three" corresponds, in broad terms, with the stuff invented by playing language games that I describe in the post above, to @Wayfarer. Seeinstitutional facts — Banno

For me the problem here is the lack of a clear account of what quantifier variance is. Hence,

This raises the issue of how the meaning of a quantifier can differ, and what the other meanings could be. And it is this issue that we tackle, arguing that one cannot make sense of variation in quantificational apparatus in the way that the quantifier-variance theorist demands. — Quantifier Variance Dissolved

So i think we can pass the argument back to those who might support quantifier variance, and ask them to set out explicitly what it is they might mean. -

Quantifier Variance, Ontological Pluralism, and Other Fun Stuff

There are three clear ways of using "is". Quantification, "There is something that is green"; equivalence: "Superman is Clark Kent"; and predication: "Wayfarer is a human".What say you? — Wayfarer

That numbers are a way of doing things does not mean that we cannot quantify over them, equate them or predicate to them.

What we have done here is to hypostatise the action of counting. This is not at all an unusual thing to do, we do this sort of thing with stuff all around us. Property, for instance, marks a difference between the actions you can perform and the actions your neighbour can perform. Money marks a difference between what a pauper can enact as opposed to what can be done by a comfortable middle-class retiree. Rank marks a difference in ability between an officer and a civilian.

But we do not spend time arguing over whether property, money or rank are "real" in the way trees and such are. Your article says "We learn about ordinary objects, at least in part, by using our senses." We do not learn who owns an object or what it is worth by simply examining it. Value and ownership are not physical attributes of an object.

We stipulate what counts as your property, what counts as five dollars, who counts as an admiral. And we stipulate what counts as two, three or four. That is we make it so by treating it as if it were so. See the various threads on Searle.

And it seems to me that this utterly undermines the misguided search for a platonic world of numbers.

That capacity, if it is anything, consists in the capacity to have something count as... An act of social intentionality of the sort that underpins much of our world.I can't help but think that it's obvious that humans do indeed have a 'non-sensory capacity for understanding mathematical truths' — Wayfarer -

Are posts on this forum, public information?Your immortal soul is indentured to @Jamal for eternity on posting.

-

Quantifier Variance, Ontological Pluralism, and Other Fun Stuffokay. For the sake of addressing the OP, it is worth pointing out that we do indeed quantify over numbers. There is an X such that X is greater than seven.

So whatever you mean when you say numbers don't exist, it can't be that. -

Quantifier Variance, Ontological Pluralism, and Other Fun StuffMeh. I could say that that's a cop out. You are just excusing yourself from answering my critique. But that doesn't progress the discussion.

I've made an attempt to tighten up your claim by pointing out its relation to free logic and modality. You have not addressed this. Presumably, if I have not understood your argument, you can point out how what you claim differed from what I offered.

So here, we are in basic agreement:

And presumably we agree there is some reification, where the act of counting is treated as if we were dealing with a series of individuals - 1,2,3...But while the symbolic form exists, what it symbolises, a number, is an act, namely, the act of counting, which is grasped by the mind — Wayfarer

But whereas you seem to be saying that these individuals are "real", I'm pointing out that they remain shorthand for an activity we can perform.

And sure, we can quantify them as needed.

So what is the argument I don't understand - is it the same one you could make a case for, but is too long? Then you might forgive my not understanding it until you present it... -

Quantifier Variance, Ontological Pluralism, and Other Fun Stuff

I just think there is a category error in supposing that numbers must exist or not exist.

Rather, they are something we do. A way of talking about things. A grammar. I've filled this out elsewhere and in previous conversations with you.

But this is not the topic of this thread. -

Quantifier Variance, Ontological Pluralism, and Other Fun Stuff

Go on - you've nearly caught me, in terms of post count! :wink:I can make the case for it, but it would be a very long one. — Wayfarer -

Quantifier Variance, Ontological Pluralism, and Other Fun Stuff

I don't recall this - where is it?See Popper — J

Nice use of Russell. It looks to be a precursor to discussions of private language.

seems to want two sorts of quantifiers, real and exist. He's immediately committed at least to some sort of free logic. He is giving us permission to talk of things that do not exist, but are real - like numbers.

That's one way of using ∃ as a quantifier and as a predicate - in this case, ∃!, such that ∃!t=df∃x(x=t). But this is just to create a short form, and permit empty singular terms.

Are there two domains? Well, here I am not on secure ground, but I think there are good arguments for making use of multiple domains. For example, if there is only one domain then every individual exists in every possible world... Uy☐∃x(x=y). But I do wish to be able to say that it is possible that some things might not have existed. See Quantifiers in Modal Logic.

is content with mysticism; but I'm not. I'd prefer to remain silent than to lurch into inconsistency.

So I'll go back to the point made elsewhere, that it seems to me that domains are stipulated, not discovered. This by way of agreeing that...it doesn't start by sending a team of metaphysicians to beat the bushes and bring back an actual sample of "existence" or "reality". — J -

Is "good" something that can only be learned through experience?

There's a logical gap between the ought of ethics and the is of natural laws.But, specifically, what about natural laws? Maybe they can be derived from some ethical consideration of the good... — Shawn -

Quantifier Variance, Ontological Pluralism, and Other Fun StuffAmused to see that Hirsch's latest publication is "On ontology by stipulation".

In previous work the author suggested that many ontological disputes can be viewed as merely verbal, in that each side can be charitably interpreted as speaking the truth in its own language. Critics have objected that it is more plausible to view the disputants as speaking the same language, perhaps even a special philosophy-room language, sometimes called Ontologese. This chapter suggests a different kind of deflationary move, in a way more extreme (possibly more Carnapian) than the author’s previous suggestion. The chapter supposes we encounter an ontological dispute between two sides, the A-side and the B-side, and we assume that they are speaking the same language so that (at least) one of them is mistaken (perhaps the common language is Ontologese). The author’s suggestion is that we can introduce by stipulation two languages, one for each side, such that in speaking the A-side stipulated language we capture whatever facts might be expressed in the A-side’s position, and in speaking the B-side stipulated language we capture whatever facts might be expressed in the B-side’s position. In this way we get whatever facts there might be in this ontological area without risking falsehood. A further part of the argument consists in explaining why the stipulation maneuver applies to questions of ontology but not to questions of mathematics (such as the Goldbach conjecture). One basic point is that mathematics has application to contingencies in a way that ontology doesn’t. — Eli Hirsch

Might be interesting. -

Truth in mathematicsDavidson is just the ubiquitous On the very idea of a conceptual scheme. The argument presented there is that languages are translatable, an argument against relativism. Plenty of threads on that topic in the forum.

Midgley has it that there is a difference between various ways we talk about the world, especially between scientific and moral or intentional language. In various of her later books.

There's a prima facie disagreement here, but I think it is on the surface only, that Midgley is espousing something not too dissimilar to Davidson's anomalism of the mental.

This is mostly a problem for consistency in my own accounts, not something of direct relevance here.

But see the thread mentioned here:

I started a thread here a while back that might be of interest. — J -

Truth in mathematicsOntology concerns bigger questions — Wayfarer

So you have said. But what they might be, apart from hand waving, remains obscure. And not so germane to this conversation. -

Truth in mathematics

Indeed, a distinction that I can't make sense of. Ontology is choosing between languages. It consist in no more than stipulating the domain, the nouns of the language.I prefer to think of it more as an ontological question. — Wayfarer -

Quantifier Variance, Ontological Pluralism, and Other Fun Stuff

This looks agreeable.An example might be helpful. I say “numbers exist”; you say “numbers do not exist”. Each of us would have to use Ǝ to formulate our position in Logicalese. What I’m arguing is that we’re each going to use Ǝ the same way, as we state our respective contradictory positions. The difference in our statements is not at the subsentential, quantifier level. We have no quarrel about "variation in quantificational apparatus." We differ on what exists, not on the use of the quantifier. — J

Isn't there variation in the domain, in what we are talking about, while quantification remains constant?To summarize: Is it the quantifier whose meaning changes, or the sentences in which the (unchanged) quantifier occurs? And if the latter, is it still QV? — J

That is, we can bring in Davidson's argument against relativism. If we are even to recognise that there are two domains, we must thereby hold quantification constant.

(This is too brief - just me trying to recall the line of thought I was following.) -

Truth in mathematicsOh, that thread dropped of my list. I didn't see your last reply. Still the most anoying question on the forums.

Yes, that's the issue on Tarskian's thread.

It brings out the conflict in my own arguments, between Midgley and Davidson, and provides something of a logical frame for that discussion. No small topic. So I'm not surprised to see it here as well.

But for here, it seems that has come around to an antirealist position, after 's "the structures themselves are nothing more than formal systems". A more direct rout than I was taking. Nice work.

's is not just a "terminological question". It's (potentially) a choice between grammars, between languages. Which implies quantifier variance. Which I think we (you and I) are inclined here to deny. -

Is "good" something that can only be learned through experience?

Ok. That's right, in so far as what is enshrined in law is what we enact. But of course there is no equivalence between the law and the good. There are bad laws.Yet, take the example of good being defined, not by an individual; but, by the very values people or groups enshrine into laws. — Shawn

My question was, "How could one decide if a proffered definition were correct, apart from comparing it to experience?" Along with Moore, I doubt that it is possible to give a satisfactory analysis of "the good"; and along with Wittgenstein I take it that one recognises it when one sees it.

But as well, we are talking here about our interactions with others. Ethics begins as one takes other folk into account. -

Truth in mathematicsI didn't say it did. My point was more that you might be accused of accept realism in your premise, in supposing that ℕ exists. But the point is now moot. Cheers.

-

Truth in mathematics

-

Is "good" something that can only be learned through experience?Do you agree with this, namely that the notion of good in inherent in the primacy of experience, and not something that can be learned by simply looking up a definition and analyzing it? — Shawn

How could one decide if a proffered definition were correct, apart from comparing it to experience?

Yes, the meaning of "good" is shown, not said; found in use, not in analysis. -

Trusting your own mind

Yes....earnestness is not imbued into what we say, it is demonstrated; as you say, it is “shown”, by not “abandoning”. — Antony Nickles

This is an excellent analysis.I would say that these “movements” and “feelings” and “actions” do not follow from the word (as if “I am earnest” were a report of something in me, and not just in the sense of a promise, though only believed as much as “I’m not lying”). Everything follows from my being convinced, my judging that you are earnest, which conclusion is “triggered” by the standards, or criteria, that we associate with earnestness—the actions and words that demonstrate you are in earnest. — Antony Nickles -

How to wake up from the American dreamI want to work Roland the headless Thompson gunner into a clever post, but this will have to do.

-

Purpose: what is it, where does it come from?

Folk appear to have missed this constraint you placed on the topic.I do not here mean any sort of instrumental purpose, either as a cause or any kind of interim goal. — tim wood

There's also some overgeneralisation. "Being alive" isn't the purpose of a worker bee. They are there only to serve the hive, even at the expense of being alive. -

Purpose: what is it, where does it come from?But the purpose one gives to oneself, or accepts for oneself, that, it seems to me, must come from within, found or made - though maybe advised from without, thus perhaps correct to say self-given. — tim wood

Well, yes, I think that is what I said. There might be a need to guard against having a private purpose; one not apparent in any action.

"Boot strapped"? not sure of the sense there. An explanation in terms of purpose may be sufficient - My purpose in drinking was to quench my thirst, no further explanation is needed. -

Purpose: what is it, where does it come from?"Proper function for which something exists" (EtymOnline). — Leontiskos

V. late 14c., purposen, "to intend (to do or be something); put forth for consideration, propose," from Anglo-French purposer "to design," Old French purposer, porposer "to intend, propose," variant of proposer "propose, advance, suggest" (see propose).

Generally with an infinitive. Intransitive sense of "to have intention or design" is by mid-15c. According to Century Dictionary, "The verb should prop. be accented on the last syllable (as in propose, compose, etc.), but it has conformed to the noun," which is wholly from Latin while the verb is partly of different origin (see pose (n.2)).

N. c. 1300, purpus, "intention, aim, goal; object to be kept in view; proper function for which something exists," from Anglo-French purpos, Old French porpos "an aim, intention" (12c.), from porposer "to put forth," from por- "forth" (from a variant of Latin pro- "forth;" see pur-) + Old French poser "to put, place" (see pose (v.1)).

Etymologically it is equivalent to Latin propositum "a thing proposed or intended," but evidently formed in French from the same elements. From mid-14c. as "theme of a discourse, subject matter of a narrative (as opposed to digressions), hence to the purpose "appropriate" (late 14c.). On purpose "by design, intentionally" is attested from 1580s; earlier of purpose (early 15c.). — Enynonline

Fuck off. -

Purpose: what is it, where does it come from?...that there exists an X such that 1) X provides purpose in the world, and 2) if there be no X, then there is no purpose, that the world is without purpose. — tim wood

Nice.

i think you are right that this is a sort of "default" analysis of purpose. The trouble is that it encourages hypostatization by treating "x" as an individual, a thing that might be located in the world, and so folk go off in search of it.

But they will not find it, because purpose is given to things, not found in them. The purpose of a knife - the ubiquitous example - is not found in a physical description, but in the way it is used. "Ultimate underlying meaning and significance" is found in use.

So yes, purpose is invented by mind, in setting forth the use.

Or, to put the same point in a somewhat different way, purpose comes from our intent. In a way, it is for our intentional descriptions what causation is for our physical descriptions. purpose, then, is dependent on the descriptions we have at hand - He flicked the switch, turning on the light and alerting the burglar, but the purpose of turning on the light was not to alert the burglar.

So, in answer to your title, purpose is the use to which something is put, and comes from our intent. It is grounded in our intentional explanations for our actions, and has worth only in terms of those intentions and actions.

Edit: That is, no big grand universal purpose, just small wantings and doings. -

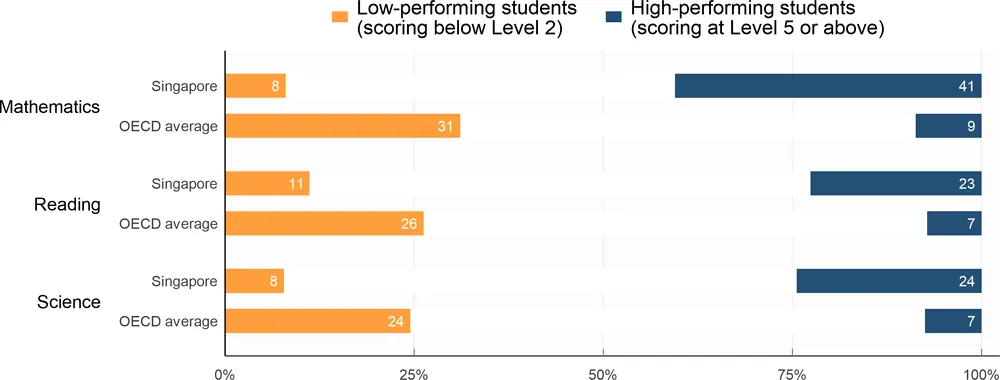

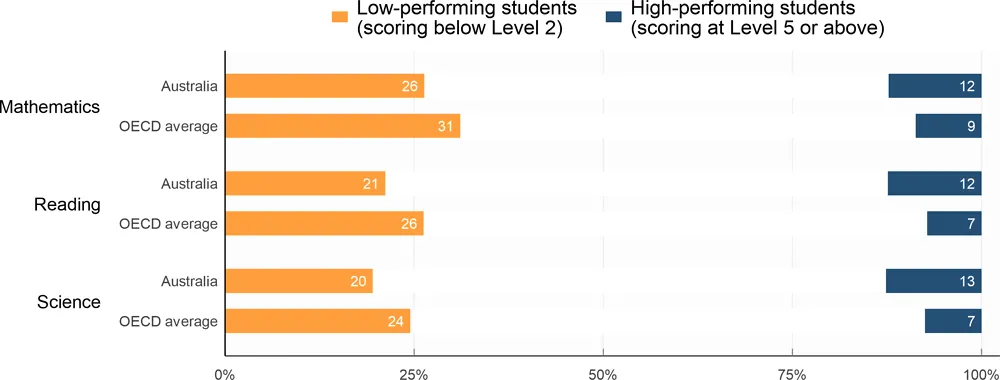

Philosophy as a prophylaxis against propaganda?Aust and US are more similar that I would have guessed. — Tom Storm

Australia consistently outperforms the US, however our results are in decline. We've had the answer before us for decades - our private school system is overfunded, resulting inequity and a burgeoning bottom-end in standardised tests. Gonsky was never implemented*.

We also have a tendency to adopt one-size-fits-all approaches from the UK and the USA, rather than say the autonomous open approaches of Scandinavian countries. Put simply we tell teachers what to do instead of allowing them their professional judgement.

Here's a quick list of the points I would make:

- Critical thinking is not peculiar to philosophy. It is learned in other subjects.

- Globally, critical thinking has a low priority, even in those countries with outstanding results in education.

- Other factors, such as student autonomy, may have a much greater impact on resistance to authoritarianism

- Comments here tend to the parochial and anecdotal. The topic can be made subject to empirical research, and there are results available for discussion.

- Those on a philosophy forum are likely to over-value philosophy.

*...because Gillard was beholding to the Catholic education system, and Turnbull to the private elite. A proper political fuckfest. -

Philosophy as a prophylaxis against propaganda?Where does the dunning-kreuger effect play into this? — Benj96

I don't see how it does. Dunning-Kruger may be explicable in terms of regression to the mean, or at least reducible to the better-than-average effect. -

Philosophy as a prophylaxis against propaganda?

So let's take it as an example.Singapore: Singapore's education system has historically placed a strong emphasis on rote learning, although there have been efforts in recent years to promote more holistic learning approaches.

Here's a graph of Singapore's GDP since 1960

The OECD notes three phases in Singapore's eductaion policy.

- Survival-driven phase: 1959 to 1978

- Efficiency-driven phase: 1979 to 1996

- Ability-based, aspiration-driven phase: 1997 to the present day

Critical thinking and philosophy do not figure in this report. Singapore consistently ranks highly in PISA scores. And not just by a little bit:

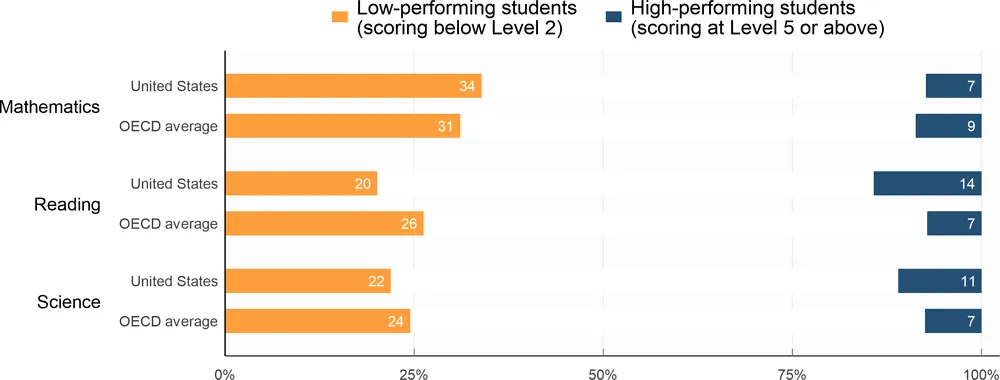

Here's the US:

And Australia:

Singapore ranks 69th on the Economist Democracy Index. But both Japan (16th) and South Korea (22nd), also on your list, rank above the USA (29th) on that index. Australia is in 14th place.

What to conclude here? Not much. We do know that education leads to democracy. See for example Analysis Of The Relationship Between Democracy And Education Using Selected Statistical Methods

Other factors remain unconsidered on this thread - student agency being the obvious one. Students who learn to take responsibility for their education may well be less disposed to authoritarian demands. -

How to wake up from the American dreamSo I guess the rollerskating didn't work out for you?

Bummer.

Why do you care? Maybe go do what you want anyway. I'm guessing that "civilisation" will look after itself, regardless of what you do.If everyone only did work that they “loved and believed in,” civilization would collapse in a week maximum. — an-salad -

Philosophy as a prophylaxis against propaganda?

How should this be understood - "Is there someone such that without them there would be no philosophy in any possible world?" Well, no, there isn't. Philosophy is only incidentally about individuals.Do you think there are philosophers who are more necessary than Plato and Aristotle? — Leontiskos

There'd be a difference between acknowledging the need for cabinet makers and insisting that everyone be taught cabinet making in primary school. And yes, urbane life would be much less comfortable without plumbers; but while it is helpful to be able to change a washer, it doesn't follow that we all need to be plumbers.

In so far as logic gives us a way to talk about language, and philosophy has language as its principle tool, Logic must be central to philosophy.

Good post.

Once we would have done Greats, but now it is difficult to even find a teacher. I'm not entirely sure that this is not a change for the better - although I do have trouble with Universities that do not have an Arts or Humanities faculty. Are they really universitas magistrorum et scholarium? -

Philosophy as a prophylaxis against propaganda?Ok. I'll indulge in a little flow of consciousness, if that is alright.

I spent a few hours yesterday looking at Classics undergrad courses. They are a bit scarce. ANU did offer pretty much just what I was after a few years back, but it seems to have dropped off. I might contact them next week and check.

This, because I've sometimes regretted not having studied Greek and Latin. It'd help me make sense of the likes of Anscombe and Nussbaum.

But philosophy did not stop at Aristotle, or even Aquinas. They are interesting, even fun, but not necessary.

So back to:

JGill is right, critical thinking is not tied to philosophy. I used critical thinking most extensively as an undergrad, in studying archeology and anthropology. But whereas other subjects make use of critical thinking, philosophy, perhaps exclusively (but psychology?), makes critical thinking it's topic. If you are thinking about how best to think, you are no longer doing maths or environmental studies, but something else.Not so sure philosopher and critical thinker are one and the same. — jgill

It's a mistake, then, to think that because philosophy is not taught explicitly, it's not taught at all.

It's a mistake, also, to think that because critical thinking is not taught explicitly, it's not taught at all.

When I taught technology, I did so using a design, make and appraise model, quite explicitly. I also took that model further, using it in teaching how to write essays, plan meals, or mediating disputes. What is that, if not critical thinking? But I didn't call it that.

So good thinking is not limited to philosophy, but it is the place where may be made explicit. And philosophers have much to say as to what makes thinking good or bad.

But teaching this stuff formally, as part of the curriculum, is unnecessary and probably counterproductive. Only some folk will have the stomach for it. The rest will reject it. -

Philosophy as a prophylaxis against propaganda?Sorry - I was distractedly spinning apples in my mind. Granny Smith, but I changed its colour to blue, just to be different. Then I went off on a sidetrack, about spinning it from inside to outside...

-

Philosophy as a prophylaxis against propaganda?

That's just what they want you tho think...A concerted engagement with the texts is needed if one is to decide for oneself. — Paine

:wink: -

Are there any ideas that can't possibly be expressed using language.Following through on my previous post.

Then on what basis can you be sure it was an idea, and not a sensation, a sentiment or an emotion? If the idea can't be set out, who's to say it is an idea?Imagine that one day, you get the best idea in the world. You go to tell your friend, but then you realize something: You don't have any words to describe your idea. Is this scenario possible? — Scarecow

Can you put it in to action? If so, those acts can be described. If someone sets out the actions involved in your idea, haven't they set out the idea?

These are not rhetorical questions. They are intended to be answered, or at least responded to. At issue is what is to count as an idea, and whether what was set out in the OP can be counted as an idea, and so to answer the first question.

But infinity can be expresses in language. It's a number greater than any countable number. There are other definitions, found in mathematics, which is part of our language. Sure, you can't count to infinity, but we have a pretty clear idea of the nature of infinity, well-expressed in our various languages.I can only think of one example of an idea that can't possibly be expressed using language. The idea of infinity can't be properly expressed using language, but then again, infinity is a word. — Scarecow -

Philosophy as a prophylaxis against propaganda?Do you think the emerging romantics who want to go back to the Greeks count as philosophy or is this just a romantic nostalgia project? — Tom Storm

You might very well think that. I couldn't possibly comment. :wink:

Banno

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum