Comments

-

No child policy for poor peopleAs a poor person myself, and the child of poor people, I've decided not to have kids, and I advocate the same for others in my position (or worse positions), and I think that this would have good consequences both for the people who take that advice, the kids they would otherwise have had, and for society as a whole -- at the expense of only the wealthy, who want nothing more than an enormous starving underclass willing to kill each other (or themselves) for scraps in the service of said wealthy.

This absolutely should not be a choice made for anybody, though; i.e. it must not be law or otherwise enforced. It's just the choice that people should make for themselves. (Just like how it would be better if everybody ate healthy -- better for the people themselves, and better for society -- but there there shouldn't be dietary laws or anything like that). -

Brain In A Vat & Leibniz's Identity & IndiscernibilityYou're mistaken. Read the links. Descartes conclusion isn't that our senses are fallible but that reality could be an illusion (from senses beimg fallible) To show our senses are fallible we'd have to use hallucinations or the like as evidence. — TheMadFool

I have, and also, I've studied this professionally for years, including a term entirely about Descartes.

Descartes is trying to show that we can doubt the things our senses show us, and thus that what we think we know about reality might not be so. To show this he gives a lot of examples and hypotheticals about the senses being deceived, including ultimately the Evil Genius scenario in which all of the senses have always been fed entirely false information. The Brain in a Vat is an updated version of that same latter scenario. Its thesis is that we can't trust what our senses tell us about reality, because someone could be feeding our senses completely false information all the time.

I'm saying, translated back to the Evil Genius version of it for clarity here: maybe we can't directly tell anything about the external world, if there is one, but we can tell something about the Evil Genius himself, based on how he reacts (in the form of the false experiences he sends us) to things we do; and if there is a world that Evil Genius is in, like if he is actually a scientist experimenting on our brain in his vat, we can in principle tell something about it through his reactions to it. Or more generally, on how that external world affects our brains, even being in the vat as they are, especially in response to things we do, even being brains in vats as we are. Because if there is absolutely no communication between our brains and the world outside the vat, no signals at all being sent between them, then we are completely causally isolated from each other, and in effect are not in the same universe at all. If we are not thus isolated -- like, if people in the outside world could poke our brains with sticks, or shoot them with lasers, or see them because light can bounce back and forth -- then there is some channel of communication between the brain and the world outside the vat, that in principle can somehow be exploited to tell information about that world. The vat just makes it a lot harder than it otherwise would be if we had normal eyes etc.

But hey, we can now watch objects that emit and reflect no light at all (black holes) that are hidden forever beyond a veil of primordial glow from the big bang (the CMB), so far away from us that we will never be able to send a signal back to them, thanks to gravitational wave detectors. And there are tricks to get information off of computers in sealed rooms that aren't connected to any network, or to use software to induce physical failures in hardware at the quantum level and so enable software exploits to break hardware security. If there is any possibility of interaction between two systems, somehow it is possible to send and receive information between them. -

Brain In A Vat & Leibniz's Identity & Indiscernibility:chin: The brain in a vat thought experiment is to show that reality could be a simulation based on the fact that our senses are unreliable. I think you've got it backwards. — TheMadFool

Pretty sure you’ve got it backwards here. It’s an update on the Evil Demon: both are trying to show that the senses are unreliable because they could be being fed false input, in a magical illusion or virtual reality.

I’m saying that we could in principle discern that we were being deceiving, eventually. These far-fetched scenarios just make that much harder. -

Brain In A Vat & Leibniz's Identity & IndiscernibilityWhat's crucial is that we can't rely on our senses. — TheMadFool

That’s begging the question.

The brain in a vat scenario tries to establish THAT we can’t rely on our senses. My rebuttal to it proceeds from the assumption that we can. -

Why do we assume the world is mathematical?It is not a special feature of contemporary physics that says reality is made of mathematical objects; rather, it is a general feature of mathematics that whatever we find things in reality to be doing, we can always invent a mathematical structure that behaves exactly, indistinguishably like that, and so say that the things in reality are identical to that mathematical structure. If we should find tomorrow that our contemporary theories of physics are wrong, it could not possibly prove that those features of reality are not identical to some mathematical structure or another; only that they are not identical to the structures we thought they were identical to, and we need to better figure out which of the infinite possible structures we could come up with it is identical to. We just need to identify the rules that reality is obeying, and then define mathematical objects by their obedience to those same rules. It may be hard to identify what those rules are, but we can never conclusively say that reality simply does not obey rules, only that we have not figured out what rules it obeys, yet.

The mathematics is essentially just describing reality, and whatever reality should be like, we can always come up with some way of describing it. One may be tempted to say that that does not make the description identical to reality itself, as in the adage "the map is not the territory". In general that adage is true, and we should not arrogantly hold our current descriptions of reality to be certainly identical to reality itself. But a perfectly detailed, perfectly accurate map of any territory at 1:1 scale is just an exact replica of that territory, and so is itself a territory in its own right, indistinguishable from the original; and likewise, whatever the perfectly detailed, perfectly accurate mathematical of reality should turn out to be, that mathematical model is a reality: the features of it that are perfectly detailed, perfectly accurate models of people like us would find themselves experiencing it as their reality exactly like we experience our reality. Mathematics "merely models" reality in that we don't know exactly what reality is like and we're trying to make a map of it. But whatever model it is that would perfectly map reality in every detail, that would be identical to reality itself. We just don't know what model that is.

There necessarily must be some rigorous formal (i.e. mathematical) system or another that would be a perfect description of reality. The alternative to reality being describable by a formal language would be either that some phenomenon occurs, and we are somehow unable to even speak about it; or that we can speak about it, but only in vague poetic language using words and grammar that are not well-defined. I struggle to imagine any possible phenomenon that could cause either of those problems. In fact, it seems to me that such a phenomenon is, in principle, literally unimaginable: I cannot picture in my head some definite image of something happening, yet at the same time not be able to describe it, as rigorously as I should feel like, not even by inventing new terminology if I need to. At best, I can just kind of... not really definitely imagine anything in particular. -

Brain In A Vat & Leibniz's Identity & IndiscernibilityWhat would the information that could help us know we're brains in vats look like? — TheMadFool

A figure could appear out of thin air and tell you so, and demonstrate anything else you might want to see as evidence... like say, a feed from outside the vat, showing your brain being prodded or whatever, and the corresponding changes in your perception of reality.

But more generally speaking, if there is any way for the world outside the vat to influence our perceptions in the vat, we have some way of getting information from outside the vat. And if the things we do in the vat have any influence on the world outside the vat, then we can do something in here to provoke responses out there that then have some effect on us in here.

The exact nature of what those interactions across the vat boundaries look like depends on how exact the vat is set up, which is one of the things we would want to figured out by trying to provoke reactions out there. If so far nothing we do in here provokes any reactions out there that have observable consequences in here, then so far as we can tell we are not brains in vats. But if we are brains in vats, then in principle some things we do in here will have some consequences out there, some of which in turn will have some consequences in here, though which we could eventually tell. -

The Unraveling of putin's Russia and CCP's ChinaI don’t think the hope is for harm to the people of these countries, but for the downfall of the oppressive governments that rule them.

The answer to how to make that happen is, broadly speaking, through those people. -

Brain In A Vat & Leibniz's Identity & IndiscernibilityIf you are a brain in a vat, there are possible experiences that could inform you of that, e.g. if the people running the vat want you to know it.

So being a brain in a vat is in principle discernible from being a real normal person, so they are not in fact identical. -

The nature of beauty. High and low art.No rush, and nice to hear another artist-philosopher is here too. :-)

-

Coronavirus and employmentSo, news from a while back was that the PPP got extended such that they have until the end of December to hire old employees back, and the whole time until then to spend the loan money they get.

Still no word from my old boss on whether he is even trying to get that loan, which still makes no sense at all to me.

But when the old June 30th deadline came and went and he still didn't ask me back, I started looking for new work at my old breakneck speed, figuring it would probably take me at least a month with the trickle of jobs I expected to find available to land a new job.

Well, it's been a month and a half now, and over 300 job applications later, a grand total of 3 have responded with anything vaguely resembling interest, and then two of them dropped out of contact, while the third couldn't pay enough for me to make ends meet.

And now the enhanced unemployment has run out, and fucking congress can't get their shit together enough to even pass a temporary relief bill of whatever the minimum they have in common is until they can sort out the rest of it.

I know the real fault lies with the Republicans, but I'm still pissed off at the Democrats for not even proposing (to my knowledge) to temporarily accept the Republicans' lower offer for the time being and then fight for more later. -

What School of Philosophy is This?It worked! Thank you for finally stopping the non-OP fuffing about in this thread (it's ok by me if you want to leave a parting shot post here).

In parting, I'll leave you with: A Woman who went to Alaska, the journaled account of May Kellogg Sullivan, and her 1902 expedition into the great North State:

CHAPTER I.

UNDER WAY.

MY first trip from California to Alaska was made in the summer of 1899... — JC Dollar-Bruh

So you admit to being a sockpuppet of @Avery?

I suspect @Baden or @Jamalrob or someone might appreciate hearing about that. -

Enemies - how to treat themBut it does not have to resort to violence if the underlying systems support non-violent options. Violence is a recourse in America, but its underlying systems leave plenty of bite to non-violent means. — Philosophim

More to the point, violent solutions are unlikely to work when non-violent democratic ones are available but don’t work. If you could magically get enough people to vote the right way, you could fix all the problems in America. If you can’t even get enough people to vote, though, then you’ll have a hell of a time getting enough people to put their lives on the line for a violent rebellion to succeed.

It’s not like someone could just assassinate Trump and them all the problems would be solved. Or even all of the top politicians, in both major parties. The people who voted them into office would still be there and would just vote similar people into office again.

This is a war for the hearts and minds of America. We are our own enemies. -

The nature of beauty. High and low art.Oh shoot, that finger was supposed to be a thumbs up.

-

Ontology, metaphysics. Sciences? Of what, exactly?Unless I missed it, no one here has called either ontology or metaphysics a science — tim wood

“Science” has had different shades of meaning over history. It used the be used in a broad sense as any field of knowledge. Today it retains a little of that sense still, but increasingly means the narrower concept of a physical, natural, empirical science. Metaphysics and ontology are definitely not the latter, but are still the former. -

The nature of beauty. High and low art.You are a really good writer — Gregory

Thanks! I just wish I could do dialogue, that’s mostly what keeps me from writing the huge work of fiction I’ve been sitting on my whole life.

It would be one way to make sense of the OP's first sentence, where the operative word is (as also later on) "seems". — bongo fury

Yeah, that “seems” is meant to make all the difference; it’s not the actually being true or good that makes something beautiful, it’s the seeming true or good. Since beauty is in the eye of the beholder. If anything else I said later seemed contrary, I guess I phrased it poorly.

"Objectively superior" suggests something almost ethical or moral. To have broad taste appears to be almost morally (or at least vaguely philosophically) better than to have narrowly "low" taste; it hints at the "universal"; to have broad taste would seem to mean having universal taste. — Noble Dust

Indeed, I do think ethics interfaces with art here (although NB that “beauty” and “good art“ are not synonyms on my account; nor “high art” and “good art”, nor “high art” and the “nobler purposes” to which art can be put that I mentioned earlier).

One of the most important questions in the philosophy of art is whether the quality of art can be judged by any objective standards or only subjectively. I reject both of the more extreme types of view on that topic, that hold respectively either that there is no such thing as objective quality to art, or else that some specific kind of art held in high status by some culture is the one objectively good kind of art and everything else is bad art for its failure to comply with that standard.

I hold instead that art can only be judged objectively inasmuch as the art itself can be considered a kind of action, a communicative action, a speech-act really, but in a broader variety of media than merely literal speech. What that art is meant to do is thus fundamentally important in how it can be judged. I hold that art meant merely to entertain can only be judged by its success at being a pleasurable experience for many people, for I hold that people being pleased is an objectively good thing. Conversely, I hold that art meant specifically to be displeasing, like something meant just to shock and offend, not merely as a side-effect or a means to some other good end but just as an end in itself, is intrinsically bad art, even if it is good at doing what it sets out to do, because I hold it is objectively bad for people to be displeased.

But what any person finds pleasurable is still a subjective matter, and so art as entertainment retains always a degree of subjectivity in its judgement. However, art meant to educate can be judged by the same objective standards that the opinions it means to convey can be judged, and so in that sense some art can be more strictly judged as being objectively good or bad art. For instance, a story with an objectively bad moral can for that reason be judged an objectively bad story, even if it excels in technical aspects at conveying that moral successfully; just like art that means solely to shock and offend might be judged bad art by the standard that being shocked and offended is bad, even if that shocking offensive art is technically proficient at being shocking and offensive.

It is important to note, however, that this does not mean that every work of art that in any way depicts something objectively bad or objectively false is therefore objectively bad art. It may actually be objectively good art if it depicts such things so as to raise the question of whether they are (or could be) good or bad, true or false, and prompt the audience to try to figure out what is real or what is moral, what is possible and what is permissible. The art may also be presenting bad or false things merely for their engagement or amusement value, as entertainment, without meaning to make any claims or raise any questions at all, only to present some interesting or pleasing possibility, which can only be subjectively good or bad art to the extent that each member of the audience finds it interesting or pleasing.

It is only if the art means to depict bad things as good, or false things as true, that it thereby becomes objectively bad art, regardless of its technical proficiency at delivering that wrong message.

Circling back again to rhetoric, as the archetypical medium, for illustration: an argument that successfully persuades someone to believe something false or to intend something bad is thereby objectively bad rhetoric, even if the speaker meant his words to do so and so would subjectively consider his rhetoric good for its success, because by objective standards false things are not to be believed and bad things are not to be intended and so rhetoric is not meant, by those standards, to persuade people to do so, and in succeeding at doing what it is not meant to do, that rhetoric thereby fails at doing what it is meant to do, and is thereby bad rhetoric.

This is analogous to how a logical argument, despite being logically valid and so "good" inasmuch as technical proficiency at logic goes, can still be an unsound and so overall bad argument if its valid inferences are from false premises or to a false conclusion. I would suggest the terminology of "proficient" and "beneficent" to describe these analogues of "valid" and "sound" (or equivalently, of abstract or logical versus concrete or empirical existence). -

The nature of beauty. High and low art.Art about our ancestors is more dear to us than art about our descendants (if that even exists) — Gregory

Science fiction is sort of art about our descendants, and I think that broadly speaking that kind of thing (speculative fiction, and its analogues in other non-narrative media) is one of the highest purposes toward which art can be put.

There are many different things that art can be meant to do. It can be meant simply to engage, to be something interesting that catches people's attention and makes them stop to consider it, with no particular further reaction or another meant beyond that simple engagement, though further reactions may nevertheless occur. It can further be meant to amuse, to provoke a pleased reaction in the audience. Some philosophies of art consider works of whatever media that are simply meant to engage and amuse with no further purpose to be not art at all, but merely entertainment

But while I am fine to apply the label "entertainment" to works meant to engage and amuse, which not all art might be meant to do, I hold that entertainment thus categorized is still a subset of art as I characterize it, and that art works that are meant to do more than merely engage and amuse often do still intend to amuse or at least to engage, and so are still themselves entertainment even though they might also belong to some other, nominally loftier category of art as well. I dispute that there is some hard line between art and entertainment, with entertainment somehow more base than art; entertaining, engaging and amusing, is just one of many things art can do, and it is a fine thing for art to do.

But art can also be meant to do other things, that are in some sense more noble than mere entertainment. Art can also be meant to inspire, as in to convey attitudes towards ideas, i.e. opinions. Those opinions that art might mean to convey may be descriptive or prescriptive in nature, intending to make people feel either that something is true (or false), or that something is good (or bad). This can be construed as art being used to educate, either in the descriptive sense that word commonly connotes today, as conveying facts about reality, or in a prescriptive sense now found slightly archaic, as conveying moral norms.

Art can also be meant to educate in a less paternalistic fashion by conveying not statements, either about facts or norms, but rather questions about either, intriguing its audience by prompting them to wonder what is actually real, or actually moral; or more still, about what is possible, or what is permissible, exploring other worlds and ways of life, exotic other options of what could be real or could be moral. That, I think, is perhaps the most noble of purposes for which art can be meant. -

The nature of beauty. High and low art.

-

Ontology, metaphysics. Sciences? Of what, exactly?In "the most general terms"? That's the sticking point for me. — tim wood

Yeah. As in, what are the basic kinds of things (or stuff) that exist(s), and what is it to exist in the first place. What's sticky about that? -

Ontology, metaphysics. Sciences? Of what, exactly?I would say the distinction is simple. The actual opposition here is between ontology and epistemology. Metaphysics is the overarching discipline broken into these two complementary wings. — apokrisis

To the extent that I find “metaphysics“ a useful term at all, it’s in this way. -

Ontology, metaphysics. Sciences? Of what, exactly?I find “metaphysics” a pretty useless and potentially confusing term, and more often just say “ontology”, which seems to be the thing people more often mean by “metaphysics” anyway.

I think of ontology in turn as being about the objects of reality, the things that are real, in contrast to the methods of knowledge, about our subjective access to those objects; each of those respectively in contrast to the objects of morality, the “ends” part of ethics, and the methods of justice, the “means” part of ethics; the four of which make up the core fields of philosophy, IMO. -

What School of Philosophy is This?When someone makes someone else do something that they believe is right, that creates subjective GOOD for them. — JC Dollar-Bruh

This is the same problem right here.

Making someone do something doesn’t “create good” in any sense whatsoever. You’re basically straight up saying might makes right, which is usually a way of claiming there is no such thing as right, but you’re claiming that whatever you’re forced to do actually becomes good because you’re forced to do it, which it patent nonsense.

To get the right picture, we have to stop thinking of time from just a human perspective. — JC Dollar-Bruh

I have no problem thinking of events from a timeless perspective (and doing so isn’t nearly as mind-blowing as you make it out to be), that’s just completely irrelevant to this particular issue. -

The nature of beauty. High and low art.“Rightness” is an abstraction away from truth and goodness. The good and the true are paradigmatic examples of things that are, in their different ways, right. Beauty is not the same exact thing as “rightness” though. Someone may find something that is actually false to seem true and thus some work of art conveying that falsehood as truth to be beautiful. It’s more like beauty is a quality that we project on things with which we agree in some way; agree that they’re good, or agree that they’re true. To agree is to think something is right, so that’s where the connection to rightness happens.

-

What School of Philosophy is This?Sorry if that’s a rant, although I’d prefer to think of it more as a stream of consciousness. — Wayfarer

I enjoyed reading it, so thanks. :smile: -

The Inequality of Moral Positions within Moral RelativismSo how does the fact that you're open to them being questioned alter the issue? — Isaac

Because if reasons to question them come up, I will. Someone who does otherwise won't. That's the "blindly" part of "blindly follow": turning a blind eye towards reasons to think otherwise. -

What School of Philosophy is This?This isn't how rational argument works. You can't just say that something is a fact with nothing to back it up.

I'm not talking about what parts of the brain anything passes through. This is philosophy, not neuroscience. Furthermore, we're not talking about why people do anything at all, but how to resolve disagreements about what to do. If someone thinks (whatever caused them to think it) that something is right and someone else thinks (from whatever cause) otherwise, do they discuss it and exchange reasons to try to convince each other to agree (thus acting like there is something they are investigating together, for which there are reasons to think one way or another, and not just baseless opinions), or do they just try to win, regardless of whether or not the other person agrees? It's a simple boolean choice, no wiggle room here: do we exchange reasons and try to reach agreement, or not? NB that exchanging reasons and trying to reach agreement is precisely what I mean by proceeding as though there are objective answers to moral questions. -

The Inequality of Moral Positions within Moral RelativismHow is it a problem? The only problem with fideism that I can see is that one might be wrong about some belief and because one does not question it, one will persist in that falsity. Is there some other problem you're thinking of? — Isaac

That is exactly the problem, yes. -

What School of Philosophy is This?That is only necessary if both of those values are objectively important in and of themselves — Pfhorrest

And this happens all the time — Olivier5

You have still yet to show that. You have shown that different people simultaneously think contrary things about what is more valuable than something else. You haven't shown that there are two objectively important and yet incompatible values.

It sounds like what you're actually arguing for isn't relativism at all, but value pluralism. The archetypal example of that is, to quote that article "that the moral life of a nun is incompatible with that of a mother, yet there is no purely rational measure of which is preferable". That is to say, it's (supposedly) good to be a nun, and good to be a mother, but you can't be both (nuns must be celibate), and there's no way of choosing between them.

I disagree with that too, in the same way as I responded to your COVID question. It could be the case that both being a nun and being a mother are equally morally permissible and omissible, neither is obligatory nor forbidden. It could still nevertheless be the case that, for a particular person in a particular context, one of those choices will in fact lead to a greater outcome than the other; it just may not always be the same for all people in all contexts, and it may not be practically feasible to know which is the case even for a particular person in a particular context. It might even be the case that, if we had a feasible way of evaluating them, both choices would in fact turn out equally good for the same person in the same context.

But that right there, "equally", implies a single scale against which they're both being measured. What is it exactly that makes either of them good or bad, to whatever degree they each are, that their goodness or badness might measure the same against that scale? What would we need to know to know which was preferable, even if we can't in practice know that? Either there is an answer to those kinds of questions, in which case you have (value monist) moral objectivism, or there isn't. I think we can't know either way, but also can't help but assume one way or another, and that assuming that we can make progress on figuring out these questions is a pragmatically better assumption than assuming we can't.

Why do you persist in pretending this false dichotomy when it has been made clear a dozen times by several different people that these are not the only options? — Isaac

Because each of these "dozens of times" the supposed dissolution of the dichotomy has been refutable. Repeating yourself over and over again doesn't magically make you right. -

The nature of beauty. High and low art.So is it rightness of representation, or of things represented, or either or both? Or is it the pleasure in or anticipation of a representation or a thing? You seem to have it all of those ways. Which needn't be a problem, except the vagueness seems wedded to abstractness (whereby truth and goodness are relatively "concrete"?!), so it's a problem for me. Is it a necessity for you? — bongo fury

I do mean it all of those ways, as I went on to elaborate. It could be "right" as in true, or "right" as in good, in many different senses of "true" and "good". Just any kind of feeling of agreement, a "yeah!" kind of feeling -- which could be "yeah, that's a thing I want!" or "yeah, that's how things are!", etc.

The more abstract beauty-as-elegance I go on to talk about would be a "oh yeah, I get that!" in the apprehension of a pattern, a regularity amidst what might otherwise noise. Like when you look at a random-dot autostereogram ("Magic Eye"), and then suddenly see the image.

Metaphorically speaking, to people who can easily manage to see the Magic Eye images, which they consider "high art", an ordinary 2D image that takes no special attention to see normally seems like "low art", in that it is boring, just obvious patterns that give no "oh yeah!" feeling. While to someone who can't see the Magic Eye image even if they try, it just looks like noise, and so is boring, while ordinary 2D images have understandable and so enjoyable patterns in them, as they apprehend the patterns and get that "oh yeah!" feeling. -

What School of Philosophy is This?If something exists at one point in time to us, then it exists in all points in time to an omnipresent observer. Which means that it's existed since the beginning, which means it's intrinsic. — JC Dollar-Bruh

That is not at all what "intrinsic" means in the field of moral philosophy... or even in physics, for that matter.

See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Instrumental_and_intrinsic_value

The person making the other person do the thing they like is creating the objective good. — JC Dollar-Bruh

I am not able rightly to apprehend the kind of confusion of ideas that could provoke such a statement. -

What School of Philosophy is This?Dollars create and save lives every day. So that gives them inherent value, just like food — JC Dollar-Bruh

That’s instrumental value, exactly what I was contrasting intrinsic value with. Money is valuable for its use, like in saving lives, not as an end in itself, so you should never trade lives for money, just maximize the lives you can save, including via monetary means. So it doesn’t matter what a life is worth in dollars, just how many lives can be saved with how few dollars.

Having the scariest threat of force ~makes~ it objective that they will do something you don't like. — JC Dollar-Bruh

We’re not talking about the objective truth about who has the scariest force or who will do what to who. We’re taking about either agreeing that something or another is objectively GOOD and trying to figure out together what that is, or else it coming down to someone just making someone else do things their way whether they like it or not. -

Problem of The Criterionbefore we can answer question 2 we must answer question 1 — TheMadFool

Why? The other way around is obvious but this seems obviously not. -

How can Property be Justified?Slavery has been prolific throughout history. The are dictatorships and theocracies with few if any individuals rights and many women and girls are controlled by male relatives. Children have limited autonomy from parents. Suicide has been illegal in many places throughout time and so on.

So self ownership does not seem to be the default. — Andrew4Handel

When I say that people necessarily own themselves, i.e. necessarily have rights over themselves, I don't mean that those rights are necessarily recognized by all civilizations. To have a right and for your society to enforce that right aren't the same thing.

it was the basis for Locke's theory of property. He also talked about one's own labours. However one's own labour requires exploitation of the environment and resources and you can question what justifies that.

I think the problem I have with the property is the reification of property as something someone has some kind of metaphysical justified innate claim over rather than a tool for resource distribution. — Andrew4Handel

Yeah, I talked about that further down in the same post you're responding to, about how rights depend on the assignment of ownership, and while the former are morally "necessary" (obligatory) inasmuch as they are "a priori" (perfect duties), the latter are morally "contingent" (omissible) inasmuch as they are "a posteriori" (imperfect duties).

It's like how "all bachelors are men" is only a necessary, a priori truth given the usual definition of "bachelor"; but definitions, the assignment of words to meanings, is contingent, and only known a posteriori. If words meant other things, which they could, then different sentences would be necessarily true; and if people owned different things, which they could, then different actions would be morally obligatory.

I actually bolded that connection because it's the most important bit: "The only obligations that can be treated publicly are those phrased in terms of property with assigned ownership, procedural perfect duties; but those in turn depend on the procedural imperfect (and thus omissible) duties of assignment of such ownership." -

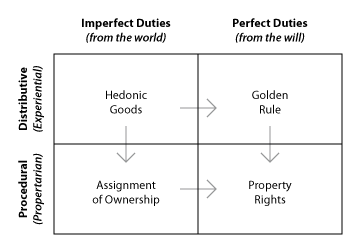

How can Property be Justified?Property is important because it’s inextricably tied up with more basic concepts like rights and procedural justice.

Procedural justice is about adherence to strict, transactional, rules of behavior, or procedures, while distributive justice is about how value ends up distributed among people as a consequence of whatever behavior. I hold that distinction to be analogous to the epistemological distinction between analytic and synthetic knowledge. Both procedural justice and analytic knowledge are simply about following the correct steps in sequence from a given starting point to whatever conclusion they may imply, analytic knowledge following just from the assigned meaning of words and procedural justice following just from the assigned rights that who has over what (which I analyze as identical to the concept of ownership, i.e. to have rights over something is what it means to own it). Likewise both distributive justice and synthetic knowledge are about the the experience of the world, synthetic knowledge about the sensory or descriptive experience of the world and distributive justice about the appetitive or prescriptive experience of the world.

Meanwhile the distinction between perfect and imperfect duties, which was introduced by Immanuel Kant, is roughly the distinction between specific things that we are obliged to always do, and general ends that we ought to strive for but admit of multiple possible means of realization. I reckon that distinction, in turn, to be analogous to the epistemological distinction between a priori and a posteriori knowledge, because just as a priori knowledge comes directly from within one's own mind (concerning the kinds of things that can coherently be believed) while a posteriori knowledge comes from the outside world, so too perfect duties come directly from within one's own will (concerning the kinds of things that can coherently be intended) while imperfect duties comes from the outside world.

Many liberal or libertarian political philosophers have at least tacitly treated these distinctions as largely synonymous, with procedural justice, matters concerning the direct actions of people upon each other and their property, being the only things about which anyone has any perfect duties, on their accounts; and conversely, distributive justice, matters concerning who receives what value in the end, being at most subject to imperfect duties, if even that. But I argue that, just as Immanuel Kant showed that the distinction between analytic and synthetic knowledge was orthogonal to the distinction beween a priori and a posteriori knowledge, so too the distinction between procedural and distributive justice is orthogonal to the distinction between perfect and imperfect duties.

At the intersection of matters of distributive justice and perfect duties lies the moral analogue of the synthetic a priori knowledge that Kant introduced. While that synthetic a priori knowledge is about imagining hypothetical things in the mind and exploring what sorts of things could even conceivably be imagined to be, this intersection of perfect duty and distributive justice is where I place the traditional moral concept of "The Golden Rule": if you cannot imagine it seeming acceptable to you for someone else to treat you some way, then you must find it morally unacceptable to treat anyone else that way.

This is very similar to but subtly distinct from the matter of property rights — of not acting upon something contrary to the will of its owner (including a person's body, which they necessarily own, i.e. necessarily have rights over), which lies in the traditional intersection of perfect duties and procedural justice — because it does not rely on any assignment of ownership, but only on experiential introspection; in much the same way that synthetic a priori knowledge is very similar to but subtly different from analytic a priori knowledge, in that it does not rely on any assignment of meaning to words, but only, again, on experiential introspection.

And of course, just as I hold there to be a category of analytic a posteriori knowledge as well, I also hold there to also be an intersection of procedural justice and imperfect duties as well, which is of utmost importance. For while distributive perfect duties are obligatory (as obligation tracks with perfect duty, and omissibility with imperfect duty), for that same reason of them being internal to the will (hence perfect duties), but not in terms of publicly established relationships of rights (hence distributive), they are not interpersonally relatable, and so are only a matter of private justice, not public society. The only obligations that can be treated publicly are those phrased in terms of property with assigned ownership, procedural perfect duties; but those in turn depend on the procedural imperfect (and thus omissible) duties of assignment of such ownership.

When we assign ownership of certain things to certain people, which is to say that the will of those people controls what it is permissible to do to or with those things, we get procedural matters of perfect duty, where we no longer need to actually do the imagining of what it would feel like to be another person being acted upon in some way, and can just deal in abstract claims. This is where we enter the realm of property rights, things that are right or wrong just in virtue of who owns what and what they do or don't want done with it, regardless of whether it actually inflicts hedonic suffering or not.

But this kind of justice in turn depends on another kind of imperfect duty, just as distributive perfect duties depend on distributive imperfect duties. Procedural perfect duty, justice in virtue of who owns what, depends on the assignment of ownership of the things in question, and that is not something that is itself a matter of perfect duty, but only imperfect duty. Nobody inherently owns anything but themselves; rather, sociopolitical communities arbitrarily assign ownership of property to people, and could assign it differently. People own what other people agree that they own, and so long as everyone involved agrees on who owns what, that is all that is necessary for that ownership to be legitimate, to conform to the procedural imperfect duties of who owns what.

But when people disagree about who rightly owns what, we must have some method of deciding who is correct, if we are to salvage the possibility of any procedural justice at all; for if, for example, two people each claim ownership of a tract of land and are each wanting to deny the other the use of it, they will find no agreement on who is morally in the right to do so because they disagree about who owns it and so who has any rights over it at all. Such a conflict could be resolved in a creative and cooperative way by dividing up the land into two parcels, one owned by each person, that would permit both people to get the use that they want out of it without hindering the other's use of it. Or the same property can have multiple owners, so long as the uses of the property by those multiple owners do not conflict in context. (Initially, all property is owned by everyone, and in doing so effectively owned by no one; it is the division of the world into those people who own the property and those who don't that constitutes the assignment of ownership to it.)

But if no such cooperative resolution is to be found, and an answer must be found as to which party to the conflict actually has the correct claim to the property in question, I propose that that answer be found by looking back through the history of the property's usage until the most recent uncontested usage can be found: the most recent claim to ownership that was accepted by the entire community. That is then to be held as the correct assignment of ownership, the imperfect duty of this procedural matter, in much the same way that satisfying all appetites constitute the imperfect duty of distributive matters. -

The nature of beauty. High and low art.I distinguish between beauty specifically and artistic merit generally, but I agree with you about the relativity of artistic merit.

Art in general is good only inasmuch as it succeeds in doing whatever it was meant to do, provoking whatever reaction in its audience it was meant to provoke. This intended reaction can again vary with who is judging the art: the artist may mean to provoke one reaction, different audiences may mean to have different reactions provoked in them, different societies may mean for art to serve some particular purpose or another, and there maybe be some objective, universal standard by which to judge what any art should do. But whatever the art is meant to do by whichever standard it is being judged, it is only good art, by that standard, if it succeeds at doing that. (Though it is nevertheless still art, even if it fails at that; it is merely bad art instead, in that case).

So an artist may mean some art piece to shock or offend the audience, and if it succeeds at that, then it is good art to the artist; but if the audience does not mean themselves to be shocked or offended, but were simply minding their own business when something caught their attention and then turned out to be something horrible they wished they hadn't experienced, then it can simultaneously be bad art to the audience. Whether there is any such thing as objectively good art depends on whether there is anything that art objectively ought to be doing, any reaction that art objectively ought to be provoking.

Philosophers of art question what the nature of beauty is, and whether it is inseparable from art, as in whether un-beautiful things can be art, and whether beautiful things are thereby automatically art. I have already answered above that I hold art fully capable of being un-beautiful, and I likewise hold that beauty does not only apply to works of art, but to any experience at all, even ones not put forth by some artist for the purpose of provoking a reaction, but just happened upon in the world. The same beautiful vista that might be captured by a photographer and turned into photographic art was already beautiful before it was made into art. Just as art does not need to be beautiful in order to be art, beautiful things do not need to be art in order to be beautiful. -

What School of Philosophy is This?I have pointed out that it is impossible to weight widely different values against one another in an objective manner. Or can you tell me how much money is a human life worth? — Olivier5

That is only necessary if both of those values are objectively important in and of themselves. In the example question you asked me about COVID management, note that even though I cared to preserve the economy, that was only because the economy is instrumentally important to human life. Dollars aren’t worth anything themselves, only lives are, but the flow of dollars can influence lives, so I advocate practices that will have whatever effect on dollars maximizes the positive effect on lives. I never have to convert lives to dollars, because I’d never trade one for the other. If someone else thinks dollars are of intrinsic value, then they’re just objectively wrong. -

What School of Philosophy is This?Whether they see these as objectively 'right' or just pragmatically something it is in their best interests to follow is irrelevant. — Isaac

My point was just that it’s one of these or the other. Either people accept the outcomes of these processes because they think they’re objectively right (or reject them because they’re wrong), or they accept them because someone will do something they don’t like to them it they don’t (or reject them because they can get away with it and escape those consequences). Either we act like there is some objective answer to be found and try to reach agreement on what it is, or it’s just down to who has the scariest threat of force. -

The Inequality of Moral Positions within Moral RelativismThis just seems to be an argument about what “blindly” means now. I’m taking that to mean what I call “fideism”: holding some opinions to be beyond question. You’re taking it to mean what I call “liberalism”: tentatively holding opinions without first conclusively justifying them from the ground up. But the latter is fine, it’s no criticism of me to say I’m doing that, and I’m not criticizing anyone else for doing that. It’s only the former that’s a problem, and you seem to want to impute that problematicness to me, perhaps because you conflate the two together, as so many do. Just like you conflate objectivism (which entails liberalism) with transcendentalism (which entails fideism).

-

The Inequality of Moral Positions within Moral RelativismYou don't have to (and can't, and shouldn't) finish any infinite series of questioning before proceeding with your life. But being open to seeing problems with the rules you live by and revising them as needed, as often and however long as needed, is the exact opposite of following them blindly.

-

What School of Philosophy is This?

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum