Comments

-

Natural and Existential MoralityHowever I will set fire to the straw man: at no point have I suggested that that which is popular becomes the answer to a moral question — Kenosha Kid

I never meant to suggest you did. The “chocolate is popular” hypothetical response was just another example of giving an “is” answer to an “ought” question.

you feel you need answers to normative questions anyway — Kenosha Kid

Everyone who ever has to make a reasoned decision about what action to take needs an answer to a normative question, because that’s exactly what normative questions are about. The only beings who never need to ask normative questions are those that act entirely in a straightforward stimulus-response way, with no reflective, contemplative function mediating the relationship between their experiences and their behaviors. Are you suggesting humans are like that? That we just do whatever we’re going to do and there’s no thinking about it to be done? I didn’t think you were suggesting that, and if you’re not then you are already admitting that normative questions matter, likely just misconstruing them as something more than they are. (The repeated references to metaphysics, the comparison to questions about God, and the talk of whether there “is” an ought, all suggest that you think normative questions are questions about some nonphysical moral entities, when they’re not at all; they’re just a different kind of question about the same ordinary stuff).

You are not asking "ought" questions but "is" questions about "oughts". — Kenosha Kid

Nope. See above.

But nature, which provided you with your moral capacities, did not provide you with any. — Kenosha Kid

It did, precisely as much as it provided me with some elementary “is” answers. My ideas of what is come from my empirical experiences: my first notion of reality is of the stuff that I can see rather than what I can’t, and every later notion of what is real is a refinement of that nature-given intuition about it. Likewise, my ideas of what ought to be come from my hedonic experiences: my first notion of morality is of stuff that feels pleasant rather than painful, and every later notion of what is moral is a refinement of that nature-given intuition about it.

One of my philosophical principles is basically just to not reach beyond mere refinement of those nature-given intuitions. Don’t start invoking the will of god or spiritual purity or things like that. I think we broadly agree in that respect. But another principle of mine is to proceed on the assumption that with enough effort and care we can establish an arbitrarily-much unbiased refinement like that. You seem to think that the latter means a negation of the former, and I think that that’s just a result of you reading unwarranted baggage into the terminology used to state the latter.

Sounds familiar. "How does the idea of a 6000 year old Earth explain the geological records?" "Oh, I don't want to bring up geology."

You're posting on a thread about naturally selected social biology. It's gonna come up. If you're just feeling obliged because I mentioned you in the OP, honestly it's fine. It's nice that you came, but I didn't aim to piss you off with a subject you don't want to talk about, and it's fine to pass. — Kenosha Kid

I didn’t say I don’t want to talk about that, I said that I’m not the one bringing it up, in response to you suggesting that I think we need to dig into all of that in order to answer a much more superficial moral question. You said:

Your counter-argument here seems to be that to weigh up, say, whether we should be a welfare state or not be a welfare state, first we must question our social biology which in turn necessitates that we must refer to the human genome which in turn suggests we must figure out our evolutionary history — Kenosha Kid

And I’m saying no, I’m not arguing that we have to do that. You brought those things up, not me. I don’t think they have any bearing on whether we SHOULD be a welfare state or not; and you seem to be saying they don’t either, because you’re saying “should” questions can’t be answered, it seems. You give an explanation on account of all that biology of why we might (or might not?) tend to be inclined to be a welfare state, and I’m not contesting any of that. Just pointing out that it doesn’t answer the “should” question.

I’m not pissed off BTW, and I’m not here because you mentioned me in the OP, but because of a comment about the is-ought divide later in the comments. My angle here isn’t that anything you wrote in the OP about biology is wrong at all, but just that that is all an answer to an “is” question, which doesn’t answer any “ought” questions at all. -

Infinite casual chains and the beginning of time?When quantum objects are entangled, measuring the properties of one changes those of the other — Relativist

Is this exactly the case? I thought it was a bit more complicated than that, but I am not a physicist and could be mistaken. Kenosha Kid? :chin: — jgill

It's close enough. If you have two entangled electrons for example, one is guaranteed to be spin-up and the other to be spin-down, but it's not defined which is which until you observe them. As soon as someone observes one of them to have one spin, it's guaranteed that the other will be observed to have the opposite spin. Regardless of distance or who observed which first, which itself is not even well-defined because from different reference frames either observation event could be considered "first".

Thinking of it in terms of one observation causing the other to change isn't quite accurate though, because what's actually happening is that by observing one particle, you're now entangled with it, and when you observe the other particle, or someone telling you what they observed the other particle to be, you're guaranteed to see a universe consistent with the other particle having been the other way, because the whole universe that you observe, containing both particles and anyone who's interacted with any of them, has to be entangled with you and the rest of everything you're entangled with, and so consistent with one particle being one way and the other particle being the other way.

(But actually, on any reasonable, non-Copenhagen interpretation, the particles are each really both ways, and you and the rest of the universe that are entangled with them are in a superposition of states corresponding to having observed the particles being one way or the other, but in every state the particles are consistently opposite each other). -

Causality, Determination and such stuff.I’m not arguing against any of that, merely distinguishing randomness from chaos as concepts. Determinism is the absence of randomness, not the absence of chaos. You could conceivably have a deterministic but chaotic system. Or a non-chaotic but indeterministic system. Or chaotic randomness, or non-chaotic determinism. They’re two separable things.

And yes, quantum phenomena are random, at least from any particular entangled observer’s point of view. (The math describing the evolution of the wavefunction itself is deterministic, it’s only at the supposed “collapse” of the wavefunction that anything random happens, and there’s disagreement about whether that collapse is a real thing that actually happens or only a shift in an observer’s perspective as they become entangled with the observed system.) -

Causality, Determination and such stuff.A pseudorandom function is algorithmic. The decay of a radioactive isotope is not. @Kenosha Kid back me up here.

-

Causality, Determination and such stuff.That is so, yes. In being “algorithmically calculable”, chaotic systems are still deterministic.

Now instead imagine a system that is not chaotic, but is still deterministic. If you change the input by 0.00001, the output changes only by 0.0001, or something proportional to that; not in a crazy complex way.

Now take that deterministic and non-chaotic system, and put a rand() function in there somewhere. Now if you put in 1, you get, say, a number between 2 and 4. If you put in 1.00001, you get a number between 2.00002 and 4.00004. But WHICH numbers in those ranges you get will vary every time you run it. The system is non-chaotic, because changing the inputs only changes the outputs a proportional amount, but it’s truly random, because even the exact same inputs won’t always give the exact same outputs. -

Natural and Existential MoralityWith utmost redundancy, we deduce that moral good is identical to that good for the survival of the group found in selected-for human social capacities — Kenosha Kid

How do you deduce this? This is precisely the is-ought problem. You have social capacities that are "good for" (contribute to) the survival of human groups, and an explanation for why humans today have those traits (they are the traits that our ancestors had, who became out ancestors because they survived, thanks to having those traits).

But still, someone asks "What ought we do?" and your answer is "We are inclined to do these things." If they ask "Yes, we are inclined that way, but is that right?" and you say "It's what helped our ancestors survive", you're still dodging the question. Saying something "is" in response to a question of what "ought" is a non-answer, unless you and the audience already agree on some "ought". You give an account on why we probably do agree on some "oughts", but that account isn't itself any answer to an "ought" question; you could just as validly point out simply that we already agree on an "ought", with no explanation needed, and then proceed from there. The evolutionary cause of our agreement isn't relevant; just the agreement itself is sufficient.

It's like if I ask what flavor of ice cream I should buy, and you tell me "chocolate is popular". Okay? Does that mean I should buy chocolate? Or that I shouldn't buy chocolate? Is popularity a good thing or a bad thing? In this case, the question is a stupid one to begin with, because the person asking the question has way more information about what flavor of chocolate would best please them than anyone else, and the question is probably rhetorical anyway. But that aside, telling them a fact about people's ice cream preferences is irrelevant, unless they already are of the opinion that they ought or ought not follow the crowds. You could tell them some evolutionary fact about why people evolved to crave certain flavors, but still that's not going to help them answer their question.

Consider sight. I look a tree, I see a tree. I look at the human genome and point a load of genes and say these are responsible for this bit of eye, that optical cable, these bits of the brain, etc. You're basically asking me where the picture of tree is. It's not there. The image of the tree is a consequence of the capacities of sight I have inherited via genes selected for because this way of seeing trees is better than my distant ancestor's for human survival. — Kenosha Kid

That's a poor analogy, because you're still entirely within the domain of "is".

A better analogy would be to flip the is-ought divide around the other way. You ask someone a scientific question about how the world is. They reply by telling you about different cultures beliefs on that topic and how it influences their way of life. You ask which if any of those cultures is actually correct about the question of fact you're asking. They tell you a story of how these cultures came to hold those views, because of the way that holding those views influenced their political or moral or other cultural development. You ask again, What is the truth of this matter?, but all they will tell you is why different people think it's good to believe this or that is the truth. Because they're a social constructivist, who believes that all of reality is a social construct, nothing is actually true or false, there's just different beliefs that are held in different cultures because believing this way or that is important to them for this or that normative reason.

That's really frustrating, isn't it? Someone who won't give you a straight answer to your "is" question, and instead will only tell you why people think you ought to believe this or that answer to it.

I just do it. Or not. Depending on the circumstances. Our bodies have this covered, as they do with so many things, without solely relying on rational input, and irregardless of our post hoc rationalisation. — Kenosha Kid

For the most part this is also true of descriptive beliefs about factual matters. We just observe what we observe in our lives and our brains just intuit what's real and what isn't. And yet there have been huge disagreements about the nature of reality across history, and we eventually developed a method of paying really close methodical attention to the experiences that inform those evolved intuitions in order to settle those disagreements, and in doing so developed a much deeper and more nuanced understanding of what is or isn't real than our ancestors had done with hundreds of thousands of years of using the same exact brains with the same exact intuitions and getting by well enough to at least survive on that alone.

I am not saying that we have to do a bunch of heavy thinking about morality every time we make any decision, any more than we need to do controlled experiments to perceive distances from other vehicles on the road: we can just see where things are with our evolved intuitions, on that scale at least. I'm only suggesting that by paying really close methodical attention to the experiences that inform our moral intuitions, we can make progress settling the huge disagreements that those intuitions have failed to settle, and in doing so develop a much deeper and more nuanced understanding of what is or isn't moral than our ancestors did with hundreds of thousands of years of using the same exact brains with the same exact intuitions and getting by well enough to at least survive on that alone.

Your counter-argument here seems to be that to weigh up, say, whether we should be a welfare state or not be a welfare state, first we must question our social biology which in turn necessitates that we must refer to the human genome which in turn suggests we must figure out our evolutionary history — Kenosha Kid

No, I don't want to bring up social biology or genes or evolutionary history at all. You're the one bringing that up as though it justified any "ought" claims. It explains why people intuitively have the "ought" opinions that they tend to have, sure, but explaining the cause of having an intuition isn't justifying content of that intuition. -

Causality, Determination and such stuff.Yes, I technically disagree, but not in a way that undermines fdrake or StreetlightX's main points. There are systems where even if you could perfectly specify the initial conditions, they still would not give the same end results. Those are truly random, non-deterministic systems. Any system where if you perfectly specified the initial conditions then you would get the exact same end results is deterministic. The impossibility of doing so doesn't actually make the system non-deterministic.

I'm not sure what your point about the Mandlebrot set is regarding chaos theory, though what you say about it sounds true as far as I know.

My point about chaotic systems is that you can have a perfectly deterministic system (where if you perfectly specified the initial conditions then you would get the exact same end results) which behaves in the way you would expect of a deterministic system, where tiny changes in the initial conditions produce only tiny changes in the output and so tiny errors in measurements of the initial conditions produce only tiny errors in the predicted output. That is a non-chaotic system. On the other hand, you could have a different, still completely deterministic system (where if you perfectly specified the initial conditions then you would get the exact same end results), which behaves in a wildly different way, where a tiny change in the initial conditions produces drastically different output, and so a tiny error in measurement of the initial conditions produces wildly incorrect predictions. That is chaos.

Determinism is about whether the output would be exactly the same given the exact same inputs. That might or might not be the case, regardless of how well you can in practice measure the exact same inputs.

Chaos is about whether or not, given a deterministic system (as above), differences in output/predictions are disproportionate to differences in input/measurement.

If we somehow knew the Galton box did behave in a perfectly deterministic manner (exact input leads to exact output; say we're dealing with a simulated Galton box) but we didn't have the exact initial state (say because we were measuring the initial condition of a real Galton box and inputting it into our virtual one), we would have great difficulty predicting even the approximate output because even the tiniest errors in the measurement of the initial state would produce huge differences in the prediction, because the system is chaotic, not because it is non-deterministic.

If the system were truly non-deterministic, then even if we rewound the virtual Galton box to the exact same initial conditions and ran it forward again, we might still get different results. -

Natural and Existential Morality"We agree with nature, it does happen to be morally good to survive — Kenosha Kid

Nature doesn’t say it’s morally good to survive. Nature just says things that kinds of things that survive more successfully tend to be the kind of things we continue to find around.

This is why I mean by ignoring the ought side. You say you’re denying it, but rather you’re just declining to answer a certain kind of question, instead giving an answer to a different question.

If someone asks whether something ought to happen, a statement to the effect that something does (or does not) happen gives no answer at all to that question. So to insist on discussing only matters of fact, and trying to twist all discussion of norms into discussion of facts, is simply to avoid answering any normative, moral questions at all, and so implicitly to avoid stating any opinion on morality at all, leaving one in effect a moral nihilist.

You’re clearly not actually a moral nihilist in practice, but if you got into a moral disagreement with someone, it sounds so far like you couldn’t give any reason why they should agree with you; you could only state the causal origins of your moral intuition and the probability that they share those intuitions given your shared heritage.

Scientism like yours responds to attempts to treat normative questions as completely separate from factual questions (as they are) by demanding absolute proof from the ground up that anything at all is objectively normative, or moral, and not just a factual claim in disguise or else baseless mere opinion. So you end up falling to justificationism (rejecting anything that can’t be proven from the ground up) about normative questions — and so denying that anything is actually moral, instead only talking above why we think things are moral — while failing to acknowledge that factual questions are equally vulnerable to that line of attack.

Someone could just as well demand an infinite chain of proofs that anything is real, and it would be just as impossible to prove it. But we accept that some things sure seem real or unreal and take that at face value and then try to sort out what seems real regardless of viewpoint and so is objectively (i.e. without bias) real. Why not likewise just accept that some things sure seem moral or immoral (as you do) and then take that at face value, act as though some things actually are moral or immoral and that that’s not just a baseless opinion that it was useful for our ancestors to have, and then try to sort out what seems moral regardless of viewpoints and so is objectively (i.e. without bias) moral? -

The four pillars of humanity.I’m interested in what anyone might have to add, change or clarify.

Poetry: the expression of human consciousness and the unconscious. Art is a product of this. — Brett

Sounds good so far, if all of the arts are encompassed within this.

Politics: ideas of nationalism. Division. Ideas of opposition. Power, the rule of law and society are products of this.

Economics: value in things, profit and loss. Power and private property are the products of this.

I think these two things are inseparable and so belong as parts of the same pillar. You even say “power” is a part of both. These are the things to do with the value structure of society.

Religion: metaphysics, belief, the unknown, the unsayable. The church, the priests and power are the products of this.

Religion has two sides to it: the side that describes how the world supposedly is, and the side that makes moral prescriptions. The part that makes moral prescriptions belongs to the same pillar as economics and politics as part of the value-structuring part of society.

But the other part belongs more with the physical sciences as something that is all about describing reality, which is a missing pillar, opposite the pillar that most of the other pillars have now been rolled into.

Also missing, opposite “poetry” / the arts, is mathematics, which is a more structural and technical, less stylistic and expressive kind of language use.

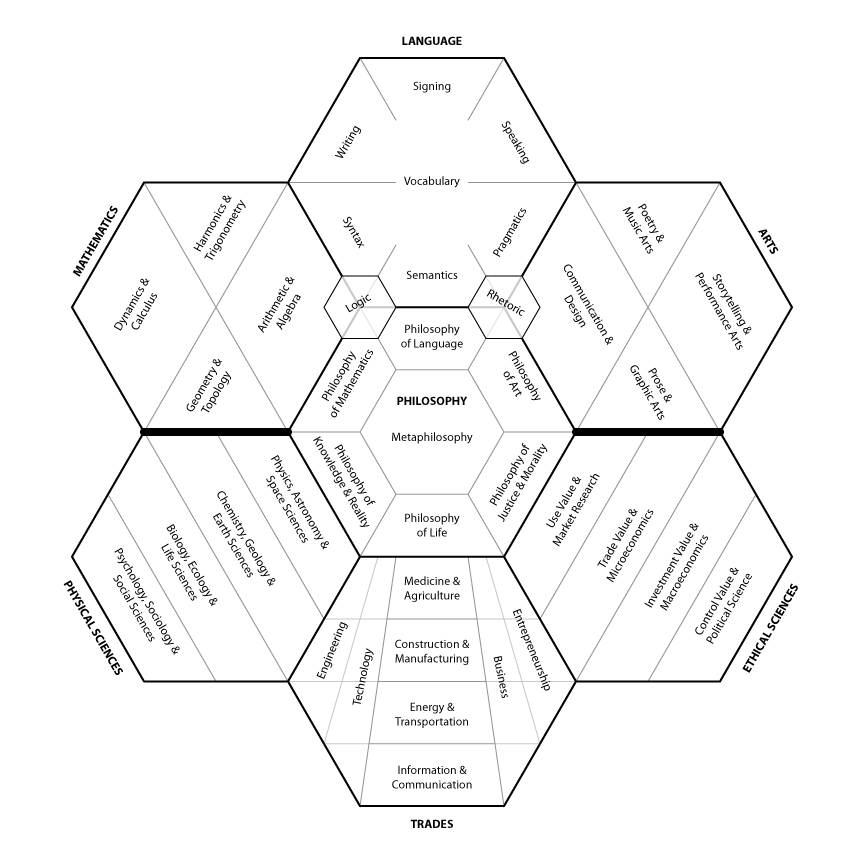

So your four pillars then could be math, the arts, physical sciences and the descriptive parts of religion, and what we might call the “ethical sciences” (economics, political science, etc) and the prescriptive parts of religion.

But since all of your four pillars are value-related except maybe a part of religion, I think maybe what you’re aiming for might be more like the prescriptive analogue of “STEM”, which I prefer to re-order as “MSET”: math, (physical) science, engineering, and technology. The analogues of those, I would say, are the arts, the “ethical sciences”, entrepreneurship, and business (administration).

Looking back to that model with math, art, physical and ethical sciences, I’d say that engineering, technology, entrepreneurship, and business all fall within a fifth pillar: the trades. And opposite that, between math and art, is a sixth pillar of language itself, in a way prior to either math or art. And then right in the middle of it all, bringing everything together, is where I’d put philosophy.

-

Alien Origins of Life - PhotochemistryThere’s no need to posit alien laser beams when our own sun is blasting us with tons of UV radiation all the time.

(And back before photosynthesis there was no ozone layer so even more of it would be reaching the surface). -

Natural and Existential MoralityThe distinction I prefer is social/antisocial. [...]

I did, perhaps regrettably, try and cast these things in terms of how a moral philosopher might see them — Kenosha Kid

In that case you are not so much ignoring the is-ought divide, as just ignoring the ought side of it completely. You are only describing why certain behaviors did in fact contribute to the survival of our ancestors and consequently why we are in fact inclined to behave that way still, but you’re not giving any account at all of why it’s good to survive and so good that we behave in that way today.

You’re also overlooking that the same tacit “passing on your genes is good” premise hidden under all of this would justify many antisocial behaviors too. Genghis Khan did a lot of antisocial stuff, a bunch of murders and rapes, and his genes are all over the world population today because of that. So does that make rape and murder good, in the right context where you’ll get away with it and have lots of successful offspring? I suspect you’ll be inclined to say no, but while you’ve given an account of how rape and murder are antisocial and so what causes lots of people to condemn them, you haven’t given any reason (not cause, but reason) for you to condemn them in the case of Ghengis Khan, for whom they were quite a successful reproduction strategy. -

Natural and Existential MoralityIf this statement referred only to your own instantaneous "hedonic experience" then depending on details your theory might be something like emotivism (or a tautology.) But your theory involves some kind of integration over the experiences of all people in all circumstances. At which point those experiences become data and you are squarely in the is-ought transmutation business. — SophistiCat

The important difference between what you’re picturing and what I’m actually saying is that on my account we are not merely to base moral reasoning on people’s self-descriptions of their hedonism experiences. Just like we don’t base science on people’s self-descriptions of their empirical experiences, but rather we replicate those circumstances first-hand for ourselves and see if we ourselves experience the same thing. Likewise on my account of morality, we are to replicate others’ hedonic “observations” to confirm for ourselves that it actually does seem bad. So we’re never starting with a description and getting to a prescriptive conclusion. We’re always starting with a prescriptivists experience (an experience of something seeming good or bad), and getting to a prescriptive conclusion.

Of course even in science we don’t all always replicate every observation everyone reports (apparently there’s a bit of a crisis of nobody doing nearby enough replication), and I’m not suggesting we have to do that with mora reasoning either. But in the case of science, when we don’t replicate, we take the (descriptive) conclusion at its word, rather than taking a description of the empirical experiences someone had at someone‘s word and then coming to the same conclusion ourselves on the ground that someone has some experience. Likewise, if we don’t replicate a hedonic experience, we’re just taking the prescriptive conclusion of the person who had it at their word — trusting them that such-and-such does actually seem good or bad — and using that in our further moral reasoning. We’re never taking a description of an experience that someone had and reaching a prescriptive conclusion from it, and so not violating the is-ought gap. We’re just trusting someone’s prescriptive claim, and drawing further prescriptive conclusions from it; or else verifying that claim with our own prescriptive (hedonic) experiences and drawing prescriptive conclusions from them. -

On the existence of God (by request)philosopher's or mystic's God — Yellow Horse

My philosopher's god would be philosophy itself, but it would be bad philosophy to call philosophy itself God, and I wouldn't abuse my god that way, so... -

Causality, Determination and such stuff.I think you think I’m disagreeing with you more than I am. — Pfhorrest

Probably. — Banno

Just to clarify what it is that I was saying, in case that turns out to be useful to anyone in this thread:

Say we had a simulation of a Galton box, simulated using Newtonian physics, so no quantum stuff going on in the simulation (and the simulator sufficiently insulated from quantum noise, as most macroscopic stuff is, that it's completely negligible for our purposes).

That simulated Galton box would be strictly deterministic. You could play it forward, note where a given marble ended up, rewind it back to the beginning, then play it forward again and know in advance where that marble would end up.

But still, that system is nevertheless (probably -- I'm not super familiar with Galton boxes) still chaotic in that the tiniest deviation in the starting positions of the balls or pins or anything would result in huge changes in the outcome.

If we had to measure the positions of the balls a posteriori and program them into a different copy of the exact same simulator, we would necessarily have less than perfect measurement of them, and so have tiny differences in the starting conditions, and so see a vastly different result.

But so long as the simulator does actually have the exact positions it used the first time, it will give the same results every other time, over and over and over again.

It is conceivable in principle (though does not appear to be contingent fact) that our universe could be deterministic like that, and yet nevertheless chaotic in places (and therefore as a whole), meaning that if we have anything less than absolutely perfect knowledge of the present (which we can't have), then we could not predict the future, even if the universe were perfectly deterministic.

And then on top of all of that: predictor systems like us are inherently chaotic, so even if the universe was perfectly deterministic and otherwise completely non-chaotic, our attempts to predict it would make it chaotic and unpredictable.

So, the universe does not appear to be deterministic, as a matter of contingent fact.

But even if it were, it could still be chaotic, and so unpredictable in practice.

And even if it weren't otherwise chaotic, any attempt to use that non-chaotic determination would make it chaotic, and so unpredictable anyway. -

Natural and Existential MoralityOne can still investigate what might exist even without assuming objective existence. — A Seagull

Without explicitly saying so sure. But if one were to assume otherwise, then there would be no point to doing such an investigation. To the tacit assumption implied by doing the investigation is that there is some answer or another to be found.

And even if one does assume that something objective does exist this doesn't mean one can also determine unequivocally what it is that does exist. — A Seagull

True, hence the rest of the principles, being open to all the options until some are foreclosed, and how to reach agreement on which are actually foreclosed. -

Natural and Existential MoralityIn doing so, you are only describing why we are inclined to do certain things, and calling those things good. You haven’t given any argument for why those things we are inclined to do are the good things. You have said what some consequences of doing or not doing those things are, assuming that you and your audience agree that those consequences are good or bad etc, but not given any argument, befitting someone who doesn’t agree, why those things are good or bad.

So you really are ignoring the is/ought divide. You’re giving a great explanation of what is, why people behave the way we do. And your implicit assumptions about what is or isn’t good fit well enough with my (and I expect many here’s) views on that topic. But your description of what inclined us to do those good things doesn’t address the question of whether they actually are good and why or why not.

If you just mean we cannot objectively prove whether or not there is anything objective to prove, then sure. But we cannot help but act on a tacit assumption one way or the other. If we assume there is nothing objective, then should we be wrong about that (we did merely assume it after all), we will never find out what it is that is actually objective, or even get approximate that. If on the other hand we assume that there is something objective, then we still might be wrong about that, but if we are wrong, we’re no worse off than otherwise, and if we’re not wrong, then we stand a chance of at least approaching an answer to what that objective thing might or might not be.

So which do you choose, assume it’s hopeless and give up completely, or assume there’s some hope out there and at least try to find it? -

The right thing to do is what makes us feel good, without breaking the lawIn summary, doing what is best for yourself and others is in fact what is best for yourself and others. — Judaka

A more substantial takeaway is: whatever feels good to someone (in their entirety, not just here and now) is what is good to them, and so what is good objectively, without bias toward anyone in particular, is what feels good to everyone. -

Refutation of a creatio ex nihiloIn the beginning there was the inflaton field, and it was without form, and void.

Then it spontaneously transitioned into a different phase exciting all of the other quantum fields.

yadda yadda yadda later the hot plasma filling the universe was without form, and void, and then the free electrons paired with the H and He ions in another phase shift from plasma to gas and there was light.

And it was good. -

Natural and Existential MoralityThey are still matters of fact that can be obtained with a sociological survey or something like that. — SophistiCat

Nope. These are the two halves of the analogy:

Something or another is the correct thing to believe (there is an objective reality) ~ Something or another is the correct thing to intend (there is an objective morality)

All beliefs are initially to be considered possible until shown false (epistemic liberty) ~ All intentions are initially to be considered permissible until shown bad (deontic liberty)

Any belief might potentially be shown false (epistemic criticism) ~ Any intention might potentially be shown bad (deontic criticism)

The way to show a belief to be false, besides simple contradiction, is to show it fails to satisfy some empirical experience, an experience of something seeming true or false (phenomenalism about reality) ~ The way to show an intention to be bad, besides simple contradiction, is to show it fails to satisfy some hedonic experience, an experience of something seeming good or bad (phenomenalism about morality)

Never do descriptive statements, that assert beliefs, thoughts about reality, factor into the process of justifying prescriptive statements, that assert intentions, thoughts about morality. -

Natural and Existential MoralityBoth of them blithely skip over the is-ought gap without even noticing: — SophistiCat

Not at all. My approach hinges entirely on the is-ought gap. The whole idea behind my approach is to look at how we handle “is” statements in science, and then handle “ought” statements in a completely separate but also entirely analogous way.

Pfhorrest operates in a more traditional moral philosopher mode in producing a recipe with statements of fact as inputs statements of ought as outputs. — SophistiCat

Where do I ever take statements of fact as inputs? I’m vehemently against the relevance of any statements of fact to moral reasoning. If you’re thinking of the most recent thread where Kenosha, Isaac, and I were discussing my views, you’ll note my main critique of Isaac’s view was in trying to reduce all moral discourse to discussion of facts. -

Causality, Determination and such stuff.So I don't see a relevant difference in kind between the marble int he tube in my example and a chaotic system. — Banno

The marble setup IS a chaotic system. I think you think I’m disagreeing with you more than I am. -

Causality, Determination and such stuff.The alternative explanation being offered by Del Santo is that the initial velocity does not correspond to some real number, but instead to some region of the real numbers. — Banno

That is just quantum mechanics. Which appears to be how reality actually works, so no problem there.

My only point was that even if the universe was perfectly deterministic at its base and errors in measurement were just errors in measurement, a chaotic system still becomes impossible in practice to predict; and a system capable of predicting is inherently chaotic, so even if the universe was perfectly deterministic, our own ability to predict it (however imperfectly) would still undermine its predictability via chaos. -

Causality, Determination and such stuff.And in this sense the path of the ball is determined.

But of course no one could determine the final resting place of the ball. Even the smallest error in the initial positions will be magnified until it throws out the calculations.

Anscombe wrote this in a time of only nascent chaos theory, which could only serve to amplify her point.

The notion that the universe is determined fails. — Banno

Determination and predictability aren’t the same thing. The whole point of chaos theory is that even a perfectly deterministic system can still be wildly unpredictable. But so long as the exact same starting conditions still give the exact same outcome always, it’s still deterministic.

My own addition to that topic: backward causation necessarily induces apparent randomness to a forward-looking observer. Prediction of the future approximates backward causation; it’s like getting imperfect information directly from the future. That is why predictive systems are inherently chaotic. So either the universe is random and so unpredictable, or else it’s deterministic and so predictable and so capable of containing predictors who would make it chaotic and so unpredictable.

Basically, so long as you have things like us who will do whatever prediction may be possible, the universe will be unpredictable, precisely because of those attempts at prediction. Even if it is fundamentally deterministic. -

Why does entropy work backwards for living systems?Negentropy is what "productive" work creates, on my account. So, closely related things, but not identical.

-

On the existence of God (by request)The phrase 'Everything is relative' is spoken emphatically by the very people for whom the atom or its elements are still the ultimate reality. Everything is relative, they say, but at the same time they declare as indubitable truth that the mind is nothing but a product of cerebral processes. This combination of gross objectivism and bottomless subjectivism represents a synthesis of logically irreconcilable, contradictory principles of thought, which is equally unfortunate from the point of view of philosophical consistency and from that ethical and cultural value. — Some Geezer

As I discussed in the pomo thread, I have observed that there are a pair of common worldviews that suffer from this exact problem but in opposite ways, differentiated along the is-ought / fact-norm divide. One of them is scientism, which is what’s described above: it takes a cynical, relativist, and therefore ultimately nihilist view toward normative topics, and while it does much better on factual topics, it often goes a little too far into a kind of transcendentally materialist ontology and elitist authoritarian academics. The other is social constructivism, which takes a cynical, relativist, and therefore ultimately nihilist view toward factual topics, and while it does much better on normative topics, it often goes a little too far into a kind of transcendentally materialist teleology and populist authoritarian politics. -

What's been the most profound change to your viewpointA blend between Pascals wager but for knowledge and Newtons Flaming laser sword (I would apologise about the classification but to classify seems to fit with your structure). Explains why PM doesn't float your boat. Appreciate you explaining. — Risk

Any time. :-) And classification is fine by me, you're right it fits my structure well.

I actually explicitly draw an analogy between my take and Pascal's Wager. The important key difference between Pascal's Wager and mine is that Pascal urges us to "bet" on one specific possibility, when there are many different possibilities with similar odds — different religions to choose from, different supposed Gods to worship and ways to worship them — leaving one forced to choose blindly which of those many options to bet on, and necessarily taking the worse option on all the other bets. Whereas I am only urging one to "bet" at all, to try something, anything, many different things, and at least see if any of them pan out, rather than just trying nothing and guaranteeing failure. To analogize the respective "wagers" to literal wagers on a horse race: Pascal is urging us to bet on a specific horse winning, rather than losing, while I am only urging us to bet on there being a bet at all, rather than not. If there is no bet, then we cannot lose the non-existent bet by betting in that non-existent bet that there will be a bet, even though we still might not win either, if there is indeed no bet to win.

But I don't think I quite fit the bill for Newton's Flaming Laser Sword, because while I think the correct way to answer descriptive questions about the world is narrowed down to by said Sword, I acknowledge that there are other things to do besides describe the world. For a major point, we also need to prescribe things, and my principles listed earlier apply equally to prescription as they do to description, not using the exact same process, but a completely analogous one. And more to the point of the original coinage of the Sword, I acknowledge that we need to ask how to do things like that, which is what philosophy is all about.

I wrote an 80,000 word philosophy book, so I'm definitely not against doing philosophy in any way. About a third of that is basically about how and why to do physical sciences (ontology, epistemology, and their implications on philosophy of mind and academics), and that largely fits the bill for the Laser Sword. But another third is about the prescriptive analogues thereof (ethics in two parts, and their implications on freedom of will and politics). And the rest of more abstractly philosophical stuff (metaphilosophy, those general principles I just outlined, what philosophies go against those principles, philosophy of language, art, and math, and then more "meaning of life" type stuff at the end, drawing from all of the preceding). -

What's been the most profound change to your viewpointI would be really interested in understanding how, coming out of a nihilistic viewpoint, you didn't land on post modernist thinking? Nihilism to me is where one lands when they realise nothing can be concretely justified and that everything requires some level of belief. Post Modernism takes that and accepts it. Recognising it cannot be an end point in itself, but that it is most likely just that. — Risk

The short version is that I realized that if nihilism were true we couldn’t know it to be true, any more than we could know its negation to be true. So all we could do is assume one way or the other.

And if you assume nihilism rather than its negation, then if there is such a thing as the right opinion after all, you will never find it, because you never even attempt to answer what it might be, and you will remain wrong forever.

But likewise if you accept fideism (appeals to faith) rather than its negation, then if your opinions should happen to be the wrong ones, you will never find out, because you never question them, and you will remain wrong forever.

There might not be such a thing as a correct opinion, and if there is, we might not be able to find it. But if we're starting from such a place of complete ignorance that we're not even sure about that — where we don't know what there is to know, or how to know it, or if we can know it at all, or if there is even anything at all to be known — and we want to figure out what the correct opinions are in case such a thing should turn out to be possible, then the safest bet, pragmatically speaking, is to proceed under the assumption that there are such things, and that we can find them, and then try. Maybe ultimately in vain, but that's better than failing just because we never tried in the first place.

And trying means tacitly assuming:

That there is such a thing as a correct opinion, in a sense beyond mere subjective agreement. (A position I call "objectivism", and its negation "nihilism".)

That there is always a question as to which opinion, and whether or to what extent any opinion, is correct. (A position I call "criticism", and its negation "fideism".)

Those together require also assuming:

That the initial state of inquiry is one of several opinions competing as equal candidates, none either winning or losing out by default, but each remaining a live possibility until it is shown to be worse than the others. (A position I call "liberalism", and its negation "cynicism".)

That such a contest of opinion is settled by comparing and measuring the candidates against a common scale, namely that of the experiential phenomena accessible in common by everyone, and opinions that cannot be thus tested are thereby disqualified. (A position I call "phenomenalism", and its negation "transcendentalism").

All of the philosophical positions I am against seem to boil down to failing one of those principles or another, so all of my philosophical positions are conversely entailed by adhering to those principles, and consequently just by a commitment to honestly trying to do philosophy in the first place. -

0.999... = 1The idea that one is a product of zero. — Metaphysician Undercover

It’s not that one is a product of zero, it’s that one is the empty product.

Take any set of factors and multiply them together. Say for example {2, 2, 3, 5}. The product of those is 60, right? Now put a 1 in there, to make it {2, 2, 3, 5, 1}. Still 60 right? Put in another 1, and another, and another, and it doesn’t change anything right? Take away a 1, and another, and another, and it doesn’t change anything, right? Including or removing ones makes no difference to the product.

So if you have the product of {2, 2, 3, 5, 1, 1, 1}, and you get rid of the 5, then the product is 12 right? And if you get rid of a 1 it’s still 12. If you get rid of the 3 then the product becomes 4. If you get rid of a 2 then the product becomes 2. We’re down to {2, 1, 1} now if you’re having trouble following along.

Get rid of a 2 and the product becomes 1. Get rid of a 1 and the product doesn’t change — still 1. Get rid of another 1 and the product still doesn’t change. We’re down to the empty set here now, {}. That has the same product as {1} or {1,1} etc because including or removing 1s doesn’t make any difference.

If you put a zero into any of those sets, the product would become zero, yes; but we’re not doing that. -

Kalam cosmological argumentYour counterargument is completely right.

And furthermore, even if the universe (as we know it) did begin to exist, whatever caused it to exist may have likewise begun to exist (as you say, we can’t exclude God from that category without just assuming otherwise), and so have been caused by something else that began to exist, which in turn was caused by something else that began to exist, and so on ad infinitum.

That is how we understand the parts of the universe to have developed over time: each finite thing was caused by some prior finite thing. So if there was such an infinite chain of finite things, that would just be the same thing as the universe as we currently reckon it.

E.g. modern inflationary cosmology posits a cause for the big bang as we know it, but that cause has a cause, and so on, possibly infinitely back. -

On the existence of God (by request)if the human reason is not trustable, what's the point to make a deduction at all? — farmer

Exactly. -

Why does the universe have rules?There are many things in the universe that, at the level of description we would use for them, aren’t law like. In fact probably most things. But then when we examine either the things those things are made of or the systems if which they are a part, we do find laws. Laws are just the patterns we find in the phenomena we experience, and if we look hard enough we can always find someone pattern somewhere at some level of description.

At least, we can never tell the difference a world with no patterns or laws, and a world with ones we just haven’t figured out yet. -

On the existence of God (by request)I suspect you’re thinking more of access consciousness than phenomenal consciousness. I take different approaches to the two. Access consciousness is a function of physical stuff, where physicality is empiricality which is grounded in phenomenal consciousness. Poetically you could say it’s minds made out of mental contents, where the “contents” are ontologically prior to the minds that later are able to contain them.

-

The role of the mediaThe news is essentially a wing of academia socially — they are public educators, in function.

The question of how to ensure that students get an unbiased education is thus a broader version of the more specific question of how to ensure news readers get unbiased information.

That entire problem is in turn analogous to the question of how to ensure fairness in governance. Avoiding bias in public institutes is the most general issue here.

Separation and balance of powers is one factor in that general solution. Applied to academia, that means separation of research, testing, and teaching: students should be tested by one party taught to them by another party from informational resources compiled by another party still.

That research then need to be peer-reviewed from a broad base. Rather than relying on primary sources directly, secondary sources like journals need to evaluate the quality and significance of those primary sources, and then tertiary sources like encyclopedias and textbooks need to compile the consensus opinion of those secondary sources.

The teachers then need to teach from those tertiary sources. Teachers need to be free to choose their sources to teach from, and students need to be free to choose their teachers.

When it comes to news, this fleshes out to a network of independent on-the-ground reporters submitting their primary research, an array of various secondary sources evaluating those reports, and then lastly some tertiary bodies compiling all those evaluations. It is those tertiary compilations of the evaluations of the primary reports that the news should be passing on to readers.

The money then needs to flow the other direction, from reader (even if via ad impressions; or perhaps even some kind of government news subsidy?) to newspaper to tertiary source to secondary source to primary reporter.

What we basically have right now is the equivalent of primary researchers teaching their “latest findings“ as though it was already settled science directly to undergrads. The whole filter of sanity checking and consensus building is missing. -

On the existence of God (by request)We can't help ourselves, as Popper saw. We creatively project structures/uniformities on the world. So where is the choice you mention? — Yellow Horse

We cannot help but assume one way or another, through our actions. The choice is which way to assume, by which actions we take. -

What's been the most profound change to your viewpointNothing in my short time of this forum has changed my views, but my views have changed drastically over the course of my life, although they were more or leas settled by my late 30s, about a decade ago.

I was raised in a religious family, and so in my early childhood held unexamined and innocuous-seeming religious views. I never had a reactionary moment in my life where I strongly rebelled against those. Instead, I slowly grew out of them as I aged and learned more about the world. I was in fact surprised in my adolescence to realize that adults sincerely held those views, and didn't merely teach them as metaphorical stories for children.

The new views that I grew into amid my adolescence were themselves, in retrospect, mere secularizations of views structurally similar to the religious ones I had grown out of: faith placed in learned academics to be the authorities on knowledge and reality, and in responsible politicians to be the authorities on justice and morality; merely replacing faith in some divine authority, which might well not even exist, with faith in the correct human authorities, whoever they should turn out to be. As I approached adulthood, however, my views grew increasingly skeptical.

Focusing on how to determine who the correct human leaders were to guide us to knowledge and justice, the right emphasis increasingly seemed to be on methodology, not authority. The correct academics to trust to lead us to knowledge were the ones dedicated to the correct scientific method; and the correct politicians to trust to lead us to justice were the ones dedicated to the correct system of rights and duties. And with such methodologies identified, it seemed not to matter who employed them, as anyone using them would have as much claim to authority as anyone else using them, effectively undermining all claims to special authority on either knowledge or justice.

But that in turn raised the question of how to identify the correct methods that would lead us all to knowledge and justice, if only we could get people to follow them; and whether there actually were or even could be such methods at all. I had definite opinions on what the correct methods were, but skeptical infinite regressions that I learned more about as I studied philosophy continued to undermine the very possibility of ever grounding any opinion on anything, leading me eventually far away from my earliest faith in divine authority, far from any trust in human authority or even in individual human ability to pursue knowledge or justice ourselves, into a nigh-nihilistic depression where it seemed any claim about anything must be denounced as just as equally baseless as any other.

That philosophical depression coincided with an actual period of depression about my own life circumstances, around the same time I finished my philosophy degree. The way I eventually found my way out of that real life depression turned out to also be the key to salvaging my philosophical views from abject nihilism, eventually building my way back up to views somewhere around the middle of that wide range I had crossed between early childhood and the end of my philosophical education. -

On the existence of God (by request)I like 'falsifiable' theories, but doesn't this notion of falsifiable depend on the uniformity of nature? A theory makes some bad predictions or leads to a disaster, so we abandon it. But maybe the world will change so that the theory becomes vital. — Yellow Horse

Every theory is just postulating that the world is uniform in such-and-such way. To falsify it is to show that the world is not uniform in that way. But that tells us nothing about whether the world is uniform in some other way. We can never prove or disprove whether or not it is uniform at all, only assume one way or the other; and we cannot help but tacitly make such an assumption by our actions, choosing to search for the uniformity we presume is in there somewhere, or not.

What you're saying, is that whatever is not empirically detectable can't be considered real. Basically, and I know you will object to this, this is empiricist positivism - that only what can be known or detected by the senses (augmented by instruments) is real or able to be considered. — Wayfarer

Nah, I don’t object to that, so long as we’re only talking about description of reality. My only real objections to positivism are that they were generally confirmationists / justificationists (“verificationists”) rather than falsificationists / critical rationalists, and more importantly, that they refused to engage in or acknowledge that there is more to thought than just description; especially, prescription is an equally important activity, with a whole philosophy comparable to their descriptive philosophy needed to underpin it.

However this excludes as a matter of definition the domain of what is subjectively real. — Wayfarer

I don’t view the objective and the subjective as cleanly separated. Empirical experience is inherently subjective; objective reality as I construe it is just the limit of accounting for more and more such experiences, gradually removing subjective bias in the process. In holding reality to consist entirely of empirical stuff, I’m denying that there is anything utterly beyond subjective experience, affirming that objective reality is made of the same stuff as our subjective experiences; it’s just ALL of them, rather than only some.

Of course, you do allow for the reality of what you consider to be ecstatic states of being, which you (fallaciously, in my view) equate with Nirvāṇa. — Wayfarer

You clearly know more about Buddhism than I do, so I won’t argue about whether or not the kind of state I call “ontophilia” really is or isn’t the same thing as “nirvana”, but I would like to explain why it seems so to me.

Essentially, it is because in ontophilic states as I’ve experienced them, there is a sense of utmost peace and detachment. There is so much positive feeling welling up from inside about nothing in particular that it feels like one could not possibly want for anything, such that even death of oneself or the whole universe is not a frightening prospect. At the same time, because of that same overwhelming positivity, it seems intrinsically worthwhile to keep on living, and to keep the world going well too. Either living forever or dying right now, or anywhere in between, seem acceptable. Everything seems acceptable. There is no want or longing.

In contrast, the opposite of that feeling, “ontophobia” as I call it, is existential dread, where one is constantly afraid of death, yet also finds living to be a misery, and the prospect of living forever seems a fate perhaps worse than death. Nothing is acceptable, and one feels a bottomless hole of perpetually unfulfillable desires inside them, a hunger for something that can’t exist, and so a hunger that can’t possibly be sated.

As I understand it, nirvana is supposed to be just such a state of detached contentment, the extinguishing of all desire, the opposite of existential dread. So it really sounds like what I mean by ontophilia. -

On the existence of God (by request)not because we can prove or explain it — Yellow Horse

We can’t conclusive prove anything about the external world, only disprove. And uniformity or explainability is not something that can ever be disproven, only something we can give up on or keep trying at. (Any particular claim that it is uniformly some way or explicable in some way is falsifiable, though). -

Is there a culture war in the US right now?Sure, and I’m not saying anything contrary to that.

-

Is there a culture war in the US right now?I wasn’t sure.

In any case, I’m not painting the entire left-right divide as exactly like what I just described, but rather noticing that symmetrical deviations from that nice neat philosophy closely match two extant ideological groups. All the people in those groups are going to vary a lot. A general pattern isn’t a strict law

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum