Comments

-

John Hawthorne's: Superficialism in OntologyThanks for the explanation. I guess I have superficialist leanings myself. I don’t find that first argument particularly persuasive (there’s no reason I see why it couldn’t be that some disagreements are substantive and others superficial, or that the superficialities of some arguments would be apparent but not of others). I’ll need more time to digest the second argument.

-

Why we cannot prayIt suggests that a lot, if not most, of people who pray have disagreed with you, and thought begging was an adequate description of what they were doing.

-

My own (personal) beef with the real numbersStarting mathematics from the natural numbers is pretty natural. If you begin with nothing but the empty set and the sole sufficient operator of joint denial, the simplest new operator you can build is disjunction, and the simplest thing you can disjoin with the empty set is the set containing itself, and hey look that’s the first iteration of the successor function and if you keep doing that you end up with the natural numbers.

-

Being and the notion of GoodWe’ll need a bit more to go on than that, but the first thing that comes to mind is Plato’s “Form of the Good”.

-

Social ResponsibilitySo neo-liberal is the opposite of old-school liberal. — god must be atheist

Not really. Historically and in most of the world outside America today, “liberal” means what in America is usually called “libertarian”, because “liberal” in America had come to mean somewhat the opposite of what it historically had meant. In most of the world “liberal” is contrasted with “socialist” and is the main form of conservatism. (And a “libertarian” is a kind of socialist, just to make things extra confusing). -

How important is (a)theism to your philosophy?Checking up on this thread months later, I am surprised to see that atheists for whom that's a core part of their philosophy are now the second-largest group of voters in this poll. I really expected the first and last options to be the biggest ones. I wonder if it's just because most people here are atheists? (I sure don't get that impression from the topics that get posted, but maybe theists are just more prolific topic-creators).

-

John Hawthorne's: Superficialism in OntologyHe references 'mereological nihilism' (something I hadn't prior outside of existentialist conversations) any insight here would be great. My best guess is that it's a theory that denies that existence of parts- (thanks wikipedia). — Oakwimble

Close. Mereology is the study of part-whole relations; or as I like to say, the study of "things and stuff", because "things" is the technical term for discrete objects the likes of which might be a part of a whole or a whole composed of parts, and "stuff" is the technical term for continuous substances that are infinitely divisible and so can't really have discrete parts or wholes.

A mereological nihilist denies that there are such things as composite objects, whole discrete objects made of parts, claiming instead that the only kinds of things are simples, basically "atoms" in the old sense, indivisible objects, and combining them together doesn't make a new composite object, it only makes a collection of such simples, which collection is not itself an object.

So, if for example we took quarks and electrons and so on to be the simples of our ontology, a mereological nihilist would say that there is no such thing as a chair, merely a collection of quarks and electrons and such arranged chair-wise; the chair is not really an composite object with quantum particles as its parts, there are just a lot of simple objects arranged a particular way.

I'm not familiar with this superficialism, and can't readily find an article on it on any philosophy encyclopedias I can find. Can you sum it up for me? -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectSo you're saying that, to you at least, the difference between a theist and an atheist isn't what they believe, but that the theist does something that the atheist does? More like a swimmer vs a non-swimmer (who may believe all the same things, but do things differently), than say a flat-Earther vs a round-Earther (who may do all of the same things, but believe things differently)?

(FWIW, I did learn to swim in the abstract. I distinctly remember being in the back seat of the car on the way to the pool, lamenting on how I could never figure out how to do the normal overhand crawl method of proper swimming and could only doggie paddle, thinking about it, picturing myself doing it and trying to understand how the overhand crawl thing was supposed to work, and then having a "Eureka!" moment when it all made sense in my head. We got to the pool, and I dove right in and immediately tried applying that, successfully. A decade or more later, I also figured out the three-beat weave pattern of poi spinning, which had thus far eluded me, in the same way, just thinking through the motions in slow motion in my mind, and then applying them.) -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectAn atheist says “God does not exist.”

You agree, “Yep, God does not exist.”

“So you’re an atheist too then?” the atheist asks.

“No,” you say, “because unlike an atheist, I believe that ____________.”

Please fill in that blank, with something that no atheist is going to respond to with “But I believe that too.” -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectThat's needlessly pedantic. There is... whatever God is. That's not to say that God is an individual in some set that contains more than himself. I just don't know what phrase you would use to disagree with the thesis of atheism, while avoiding using the word "exists".

-

Universe as simulation and how to simulate qualiaTo the extent that mechanics is necessary and sufficient for the explanation of a particular kind of subjective experience, simulating those mechanics will automatically simulate the experience, and there is no question left to answer.

Pretty much everyone seems to agree that the mechanics is necessary, and the question at hand is whether it is sufficient: is there something else besides mechanical behavior needed to account for experience? The eliminativist says "no", the behavior just is the experience; you seem to disagree with that, as do I. Many say "yes", it needs some special thing besides the mechanical stuff. The panpsychist like me says "yes", but it's nothing special or a different kind of stuff: it comes for free with the same stuff that does the behavior, but it is not identical to the behavior, but rather the flip side of the same thing the behavior is one side of: function. -

What’s your philosophy?Thanks! Happy New Year to you too, and best of luck on your own summa project.

-

The Notion of Subject/ObjectI have been asking about this for a while too. This also seems to underlie Wayfarer's theism somehow, where he holds that "God does not exist" but that in some sense still "there is a God", because God has being or is a being rather than existing or being an existent or something like that.

-

What’s your philosophy?Finally up to the last of my own set of questions from two months ago:

Bonus question:

What is the meaning of life? — Pfhorrest

"Meaning" in general means important or significance, so this question is asking what is important about one's life. That in turn depends entirely on how connected to the rest of the universe you are, which is to say how important a role your function plays in the overall function of the universe: if a lot of processes in the universe run through you, that makes you important to the universe, and makes your life meaningful. Those inputs can be in the form of being the beneficiary of goods, having the universe serve your ends; or in the form of learning, of gathering truths about the rest of the universe to guide your own behavior; and those outputs can be in the form of doing good for others, being important and so meaningful because of your influence on the rest of the universe; or for the truths that you compile and impart unto others, the teaching that you do. So the meaning of life is to "earn" and to learn, to help and to teach: to both receive and to spread both goods and truths.

There are also feelings of meaningfulness or meaninglessness, that can vary regardless of the actual meaningfulness of one's life. The feeling of meaninglessness, which I call ontophobia, is I hold the prompt of the question about the meaning of life, and when someone is feeling that way no answer will alleviate the feeling, giving a false impression of meaninglessness. The feeling of meaningfulness, ontophilia, is on the other hand the greatest feeling imaginable, a feeling of profound acceptance and understanding, like everything is intrinsically fine and makes intrinsic sense; and being in that state of mind is both enlightening and empowering, enhancing the function of the mind and will, increasing the ability to both receive and spread both goods and truths. Achieving and spreading such a state of mind is thus a reflexive, second-order meaning of life, which is both promoted by and promotes the first-order meaning of life. -

The Notion of Subject/Object"Subject" and "object" are an indispensable part of our conceptual framework, but it's entirely possible (and I'd argue necessarily true) that all subjects are objects and all objects are subjects. "Subject" and "object" are roles, not classes of entities.

-

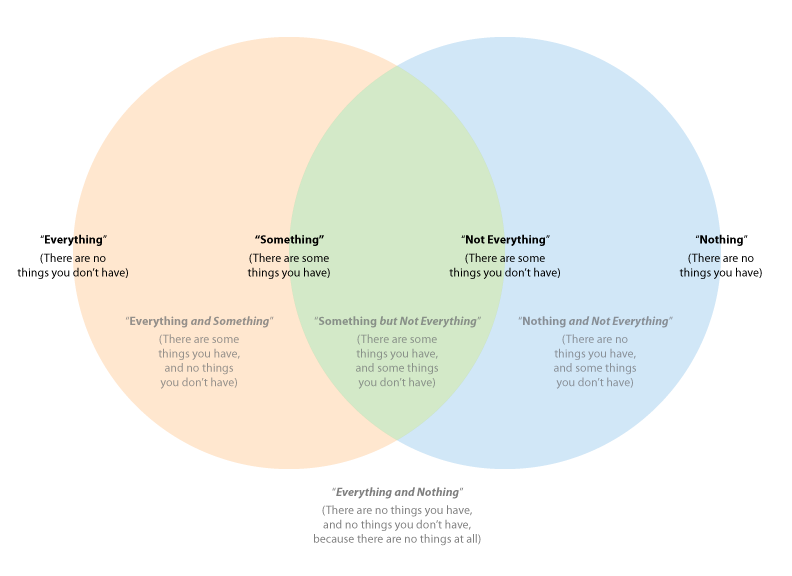

Nothing, Something and EverythingPfHorrest showed me a Venn diagram that was self-contradictory or nonsensical. When I told him that, he said, "forget the Venn diagram". — god must be atheist

I did explain briefly why it was not self-contradictory before moving on to a different approach, but since you're so hung up on it I can explain in more detail here.

To recap, the left circle is cases where you have "something" and the right circle is cases where you have "not everything". In other words, the left circle is cases where there are things that you have, and the right circle is cases where there are things that you don't have.

In the left crescent are cases where you have something but not not everything, or in other words both something and everything: there are some things you have, and no things you don't have, so you have all of the things there are to be had, and there are some to be had. This is the ordinary use case for "everything", but there is another we'll get to later.

In the middle intersection are cases where you have something but not everything: there are some things you have, and some things you don't have. These are the cases that you want to restrict "something" to, but in normal language and formal logic both Aristotelian and modern, "something" also applies to the left crescent: you can have something and everything, or something and not everything. I like to call this case "merely something", where the "mere" conveys the not-everything part of it.

In the right crescent are cases where you don't have something, and you do have not-everything: there are no things that you have, and there are things that you don't have. This is the ordinary use case for "nothing".

But in the outer area are the weird cases, or rather, the one single weird case: where you don't have something, and you don't have not-everything, or in other words, when you have nothing and everything: because there are no things that you have, and no things that you don't have, because there are no things at all, because the only case that falls out here is the case of an empty set.

I drew a picture:

-

Universe as simulation and how to simulate qualiaThis is a non-problem if you don't conceive of "qualia" as something that material things need to "produce", but just as an aspect of the being of all (material) things. To get something to have a human-like phenomenal experience, you just need to make it execute a human-like function. This has the weird-sounding implication that everything has some kind of phenomenal experience, but it's not so weird compared to the well-accepted fact that everything has some kind of function. What is the function of a rock? Not much to speak of, but a rock still does something in response to what is done to it. Why should it be so much weirder to say that the rock experiences what is done to it, than to say that it does something? We don't mean "does something" in the same robust and complex, willfull sense that a human does something; and we can mean "experiences" in a similarly non-robust, simple, non-conscious sense if we want, too, that is nevertheless still on the same continuum, of the same kind, as the robust, complex, conscience experience of humans.

-

My own (personal) beef with the real numbersAs I recall my math education, the concept of the "real numbers" wasn't even introduced until we got to "imaginary numbers" to juxtapose them with.

We had just "numbers" (natural numbers), constructed by counting (the successor function). We could do addition and multiplication on them just fine and didn't need to worry about any other kinds of numbers.

Those then became "positive numbers" when contrasted with "negative numbers", which were introduced to fill out the set of numbers that could be constructed through subtraction, which were again just "all the numbers".

Those then became "whole numbers" (integers) when contrasted with "fractions", which were introduced to fill out the set of all numbers that could be constructed through division, which were again just "all the numbers".

Those then became "rational numbers" when contrasted with "irrational numbers", which could be made in a bunch of different ways; there wasn't just one kind of operation that resulted in irrational numbers sometimes. Between rational and irrational numbers, that was again just "all the numbers", and we never had to worry about having one method of constructing any given one of them, just that there was the stuff that could be constructed through division and the stuff that couldn't.

Those only became "real numbers" when contrasted with "imaginary numbers", which were introduced to fill out the set of numbers that could be constructed through taking roots, which were, by this point, finally not treated as "all the numbers" but as a set of their own, the "complex numbers", suggesting that the reals are still considered the normal set of all numbers, and the complexes are considered some kind of weird superset made of pairs of numbers, not just numbers simpliciter. -

Shaken by Nominalism: The Theological Origins of Modernity"Miracles" and the "supernatural" cannot be relative to the current state of scientific understanding, unless you want to concede that modern westerners demonstrating our technologies to uncontacted peoples are performing genuinely supernatural miracles to them, because they lack the scientific understanding to explain how we do those things.

So if you want to say that we humans cannot perform supernatural miracles, even when other people don't understand how we're doing what we're doing, then instead "miracles" and "supernatural" must mean things that cannot in principle be explained by any science ever. That is the sense usually used by naturalists and atheists who say that there is nothing supernatural, no miracles: that anything can, in principle, eventually, be explained, even if we don't know how yet.

I argue that if we are in a state where we don't know whether or not that is true, all we can do is act in a way that assumes one answer or another, by either trying to explain things or not trying. So saying that something is supernatural or a miracle is tantamount to simply not trying to explain it. But assuming we would like to explain things, even if we're not sure if we can, it is pragmatically in our best interest to always try, and never to simply give up and thereby guarantee failure. In doing so, we implicitly assume that there is nothing supernatural, no miracles, and so on: just as-yet-unexplained phenomena, that are still natural inasmuch as an explanation is assumed (implicitly, by the fact that we're not giving up) to be possible. -

Reason as a ConceptEtymologically, "reason" comes from a root that means "to put in order", or "to fit together", which suggests that "reason" is fundamentally about understanding the relationships between things.

-

Why we cannot prayThanks for that. Looking up the root of that, it appears to come from a word that meant "praise". The audible similarity of that to "pray" makes me wonder if there was some conflation between them along the way, that gave "pray" the sense that iolo is on about, but I can't find any good source to back up that hypothesis.

-

Why we cannot prayWhy do you suppose it is that people who pray named their activity with a word that already meant “to beg”?

-

Why x=x ?

The catch is, we also know that it is nearly impossible for “nobody” to be “looking”, because anything at all counts as “somebody” and any kind of interaction at all counts as “looking”. So this boils down to saying the moon demonstrably does not exist when it stops interacting with the rest of the universe, which is in turn a reasonable definition of nonexistence, making the claim rather trivial.We now know that the moon is demonstrably not there when nobody looks. — Boojums All the Way Through - N. David Mermin -

The Kantian case against procreationWhy is there so much focus on (anti)natalism on this forum recently?

-

What is your definition of philosophy?Philosophy is the application of abstract tools from language, mathematics, and the arts, tools like logic and rhetoric, to the job of creating the tools needed for the practical sciences to do their jobs of sorting out what is true or real on the one hand, and what is good or moral on the other hand, so that engineers can create technologies that give us the right tools, and entrepreneurs can create businesses that gives us the right jobs, to accomplish anything else.

-

Philosophy and illnessOver the past year I was struck by a physical illness of unknown cause that then caused severe mental disturbance (anxiety and dread) that coincided with the pre-planned (for years) rewriting of my philosophy book, and had a major impact on the last chapter of it (on the meaning of life) which I hadn’t even planned to write until shortly before all of that happened and barely had any material for, but is now the longest chapter in the book.

-

Why we cannot prayThe sense of the word “pray” meaning to ask or beg is older than the narrower religious sense. Why do you think it is that the religious activity came to be called that, if it weren’t usually a case of doing what the word ordinarily meant: begging?

-

Why x=x ?I recall that during one walk Einstein suddenly stopped, turned to me and asked whether I really believed that the moon exists only when I look at it.

That sounds to me like a rhetorical or incredulous question meant to convey Einstein's opinion that he thinks the moon does exist when it's not looked at. -

Are we hardwired in our philosophy?Yes I’d agree. And the strength to go on doing that and not quit or take lazy intellectual shortcuts is what I meant by “strength of mind”.

-

Are we hardwired in our philosophy?It’s an open question in philosophy whether people are actually capable of acting in ways they think is immoral. Socrates famously argues that all wrong is done through mere ignorance of what is right; everyone means to do right, they just might be wrong about what that is. Though my position is subtly more nuanced, I lean in that direction myself. Weakness of will is I think the only factor Socrates misses; we sometimes do things we think are wrong out of weakness to do what we mean to do, too.

I’d likewise argue that everyone is always trying to believe whatever is true. There’s just a difference in how skilled someone is at figuring out what that is, and how much strength of mind they have to put into the effort of doing so. -

Nothing, Something and EverythingThis just goes back to how having all of something just means there are none you don’t have. If there are zero things, and you have zero of them, then there are no things (out of those zero things in question) that you don’t have. You have zero out of zero, which is the most out of zero you could possibly have, i.e. all of it.

It’s weird, yeah, but that’s because we don’t usually talk about empty sets, because there’s almost no practical need to. -

Are we hardwired in our philosophy?My changes happened for different reasons. I just kinda grew out of my religious views in the same way I grew out of Santa Claus, influenced by various sciences I learned aboard in school and in books and educational TV. My transition from communist to libertarian was heavily influenced by discussion with people on the internet in my adolescence. My descent into nigh-nihilistic skepticism was prompted by formal philosophical study. My recovery from that was the result of private philosophizing about ongoing life experiences. And my transition to libertarian socialism was the result of my own philosophizing about problems with right-libertarianism that people on the internet constantly argued about, and then independent reading to see if anyone else had come up with similar ideas who could back me up, when my “new solution” proved unpersuasive on either the right-libertarian internet communities I grew up with or the state-socialists there arguing against them. Lots of my subsequent philosophical refinements have followed that last pattern: try to extend an olive branch to the “other side” with a novel third position, piss off both sides in the process, search for other more established thinkers with similar ideas to back me up.

-

Why do we try to be so collaborative?It sounds like you reject all but the linguistic meaning of “meaning”, which is itself just linguistically false. When someone asks about the meaning of life, they’re not asking what the word “life” means in that sense, they’re asking why is life — anyone’s in particular, or all of it in general — important, or significant, in the sense of why it matters. And that’s a perfectly cromulent use of the word “meaning” that predates the linguistic one.

-

Why We Can't solve Global WarmingPlanting a trillion trees (and more) would be another way to capture CO2, and produce a lot of O in the process. A sprouted tree may take 20 years to get big enough to make a difference, but that's a workable time scale. A trillion trees, though, means less land for agriculture. In 50 to 80 years we would have a lot of mature trees to cut down to make room or more, NOT burn them, and replant. — Bitter Crank

My vague memory is something more in this vein. May have also (or instead) involved using algae, and possibly turning the biochemical product of that process into feedstock for industrial purposes that currently rely on petroleum-sourced chemistry. (Something about vast shallow pools in cheap desert land with plentiful sunlight for power comes to mind, but I might be mixing up different things here.)

Best wishes for your mental health in the coming New Year, which I also hope will be happy. — Bitter Crank

Thanks! You too. -

Why do we try to be so collaborative?Meaning is significance or importance. All of those words have linguistic senses (the meaning of a word is what it signifies, what its import it, in the sense of what information it conveys) but also the more familiar practical senses of "importance" and "significance" define "meaning" in the sense used in the phrase "meaning of life". To have meaning, to be meaningful, is to be significant or important. What is significant or important (that is, meaningful) about anybody's life? That depends entirely on how influential they are on things other than themselves, and how positive that influence is. That's a really roundabout way of saying that your life is as meaningful as the good that you do; you're important inasmuch as something would have been worse without you around.

As to the evaluation of "good" and "worse" and so on, relativism just reduces to nihilism, and nihilism just reduces to giving up on even trying to answer the question, which only guarantees that you will never find the answer. Even if we cannot know whether or not there are answers to be had, all we can then do is either try to find them if we can, pushing on even if we don't find immediate success at that endeavor; or give up and not try. We can never know that success (at answering questions of what is better or worse, etc) is impossible; only, at most, that it has not been achieved yet. -

Why We Can't solve Global WarmingI don't remember what it was now, because my retention is shot this year thanks to anxiety, but there was some news story about something, a carbon sequestration method I think, that could solve climate change, at what is objectively a reasonable cost (I recall the number starting with a 3, though of course order of magnitude is more important and I can't remember that), but is currently politically unlikely. Knowing that that technology exists gave me much hope, because there will eventually become a point when shit gets bad enough that even the rich and powerful have to deal with the consequences, at which point paying to fix the problem will become in their best interests and therefore will happen.

-

Why do we try to be so collaborative?Helping and teaching others is half the meaning of life (the other half being learning and helping yourself), inasmuch as meaningfulness means being important to the functioning of the universe, being more connected to things other than yourself. The more input to you (learning and, let's call it for the sake of rhyme, "earning") and the more output from you (teaching and helping), the more the universe flows through you, the more important you are to it. And of course you have to make sure that the information and action flowing through you are correct, which is just what truth and goodness, knowledge and justice, etc, are all about.

This makes me disinclined to engage with you further.garbage leftist ways of thinking — Judaka

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum