Comments

-

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum - an introduction thread

-

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading GroupI'm going to move onto section 2 tonight, but just the summary of section 1 and the preparatory remarks for the remainder of section 2. Hopefully this will serve to get us all on the same page before the gigantic and dense walls of text in the second section.

EDIT: references to areas and volumes that were here have been removed seeing as Riemann doesn't actually discuss them in the paper! He just talks about length notions within manifolds.

II. Measure-relations of which a manifoldness of n dimensions is capable on the assumption that lines have a length independent of position, and consequently that every line may be measured by every other.

The title itself is an orienting remark, the first section was:

I. Notion of an n-ply extended magnitude.

and now we've developed notions of n dimensional manifoldness (curves/surfaces/volumes), n-ply extended magnitudes (coordinate systems of 1/2/3 dimensions), we can link manifolds to measures of length through the following chain of associations:

n dimensional manifoldness -> n ply extended magnitude/n dimensional coordinate system -> measures of length

In moving from n-dimensional manifoldness to n-ply extended magnitude, we needed to be able to associate every point in the manifoldness with a collection of quantities in the n-ply extended magnitude, which takes the notion of the position of a point within/on a manifold and maps it to a corresponding quantity (or set of quantities) that locates the position of the point. This is the basic function of an n-ply extended magnitude or coordinate system.

Now that we have a machine which takes manifolds and labels all their points in a consistent manner, we can take the point labels and start to ask questions using them: what's the distance between a pair of points within/on the manifold and how is this related to the quantities we used to measure their position? IE, how can we link a coordinate system to a notion of length?

In §1 in section 1, Riemann stipulated that:

Measure consists in the superposition of the magnitudes to be compared; it therefore requires a means of using one magnitude as the standard for another.

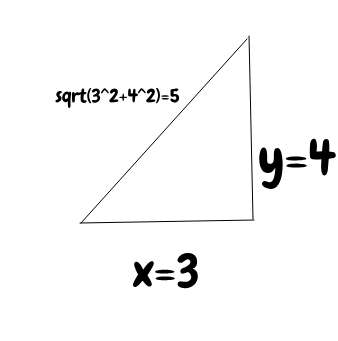

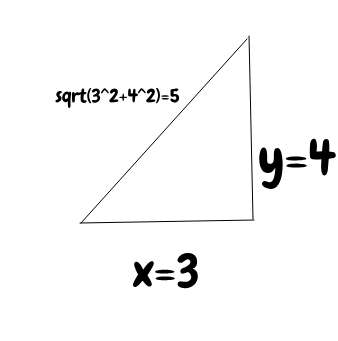

we first superposed a number of independent directions of variation to describe the position of a point on/within a manifold - taking a point in it and mapping it to a coordinate like (x,y), now we're going to superpose all those independent directions of variation in order to ascribe a length to them, like sqrt(x^2+y^2) - mapping coordinates or relative positions to quantities that represent their size.

The mechanism that described the ascription of a coordinate system (n-ply extended magnitude) to a manifold looks like this:

for every point p on a manifold of dimension n, we have the unique ascription

where we have n numbers that uniquely and completely specify the position p within the manifold.

Setting up this conception was the topic of section 1, especially the passages on how to build a manifold of n+1 dimension out of a manifold of n dimensions and a manifold of 1 dimension (with its simply extended magnitude). Riemann summarises all of the previous developments in the paper as:

Having constructed the notion of a manifoldness of n dimensions, and found that its true character consists in the property that the determination of position in it may be reduced to n determinations of magnitude (breaking a sentence in two here)

Section 2 however introduces something more similar to the modern notion of the relationship between manifold and coordinate system. It looks very similar to the one developed in section 1, but we 'zoom in' to get a weaker condition - a more local description:

for every point p there exists some neighbourhood around it such that we have the unique ascription:

where we have n numbers that uniquely and completely specify the position p within the manifold.

And this manifold is locally flat when all the numbers are ascribed consistently with the usual Cartesian coordinates when we zoom far enough in- making the coordinate geometry look flat very close up. What we're going to do now is flesh out the second arrow in the flow chart:

n ply extended magnitude/n dimensional coordinate system -> measures of length

and Riemann summarises these intentions in the next part of the first paragraph:

... (Now) we come to the second of the problems proposed above, viz. the study of the measure-relations of which such a manifoldness is capable, and of the conditions which suffice to determine them.

He then provides preparatory remarks for the remainder of the study:

These measure-relations can only be studied in abstract notions of quantity, and their dependence on one another can only be represented by formulæ. On certain assumptions, however, they are decomposable into relations which, taken separately, are capable of geometric representation; and thus it becomes possible to express geometrically the calculated results. In this way, to come to solid ground, we cannot, it is true, avoid abstract considerations in our formulæ, but at least the results of calculation may subsequently be presented in a geometric form. The foundations of these two parts of the question are established in the celebrated memoir of Gauss, Disqusitiones generales circa superficies curvas.

Firstly,

These measure-relations can only be studied in abstract notions of quantity, and their dependence on one another can only be represented by formulæ.

connotes that we will be superposing the coordinates we have ascribed to points on the manifold in order to derive notions of distance using them. Mathematically this resembles taking every coordinate as part of a function that maps to a single number. Like we can take (x,y) and map it to sqrt(x^2+y^2) to get the distance of the point (x,y) from the origin. More formally, Riemann will be constructing a localised version of something like:

which takes every coordinate of a point, combines them in some way through algebraic (and differential) operations which produces a single quantity - which is a measurement of length. Riemann will make...

certain assumptions (which ensure that the length ascriptions) are capable of geometric representation; and thus it becomes possible to express geometrically the calculated results.

which correspond to this locally-flat condition - since the space we live in (at least in a present-at-hand sense @John Doe) looks to obey Euclidean geometry/be flat on small scales, we can only draw things which have this condition even if we can stipulate different notions.

Riemann gives a final head nod to Gauss before diving right into the characterisation of flat space - what is it that makes flat space flat? It will turn out to be a measure relation of the above form. -

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading GroupMade a thing with more examples.

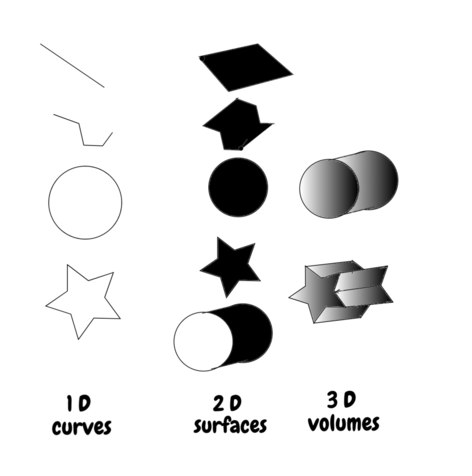

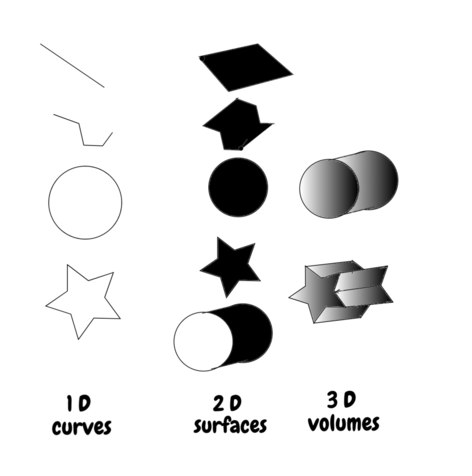

Empty areas in the 1D case because we're just considering the lines. Black areas in the 2D case mean we're dealing with all those shaded points in the enclosed area. Graduated shading areas in the 3D case means we're dealing with all those shaded points in the enclosed volume. The surface of a sphere is another example of a 2D manifold. All the points in a cube and all the points in a sphere are more examples of 3D manifolds.

Edit: imagine yourself on the manifold, with all the directions of movement the manifold allows you. 1D manifolds - you can only step forward and backwards. 2D manifolds - you can step forward and backward; and left and right, like walking on the floor of your house. 3D manifolds - you can go forward and back, left and right, and up and down - aeroplanes move in 3D, so do swimmers. If you can 'immerse yourself' in the manifold, you're in 3 dimensions. If you can 'move about freely on a surface' you're in 2 dimensions. If your movement is forced to move along a pre-determined path, your only choice being to move forward or back, you're in 1 dimensions. If you have nowhere else to travel, and no directions to travel in, without leaving the manifold you're on - you're on a point.

EDITED: Later developments in math have that 1 dimensional manifolds become associated with lengths, 2 dimensional manifolds become associated with areas, 3 dimensional manifolds becomes associated with volumes (measure theory). However the paper develops notions of inter-point distances (metrics - distance measuring functions) that lay within manifolds, rather then just dealing with the embedding space (example will be drawn later). -

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading Group

That sounds about right Moliere. You extended it correctly (by my reckoning) to the surface of the sphere, so I think we see eye to eye now.

I'm still confused about the OD point: does it count as an extended magnitude or not? — StreetlightX

Typically it doesn't, and I don't think it does for Riemann either. From the §1 in section one:

Magnitude-notions are only possible where there is an antecedent general notion which admits of different specialisations. According as there exists among these specialisations a continuous path from one to another or not, they form a continuous or discrete manifoldness; the individual specialisations are called in the first case points, in the second case elements, of the manifoldness

The important line is:

According as there exists among these specialisations a continuous path from one to another or not, they form a continuous or discrete manifoldness; the individual specialisations are called in the first case points

removing the parts which aren't talking about 'continuous manifoldness' or 'points' and paraphrasing:

According as there exists among these specialisations a continuous path from one to another or not, they form a continuous manifoldness (whose specialisations consist of) points

we have that 'points' are a specialisation of which 'manifoldnesses' consist of just when 'there is a continuous path between (every pair of) points'. Now that we've established that specialisations are points, and continuous manifoldnesses consist of points, Riemann develops the notion of a continuous manifoldness in §2:

If in the case of a notion whose specialisations form a continuous manifoldness, one passes from a certain specialisation (point 1) in a definite way to another (point 2), the specialisations passed over form a simply extended manifoldness (a path between points - a line or curve), whose true character is that in it a continuous progress from a point is possible only on two sides, forwards or backwards (in the direction of increasing or decreasing arclength).

So we have that simply extended continuous manifoldnesses consist of points. Simply extended manifoldnesses are 1D objects, because 'in it a continuous progress is possible only on two sides' - like the horizontal axis in Cartesian coordinates; we can go right or left, and going right is the same as going 'inverse' left, like up and down are both part of the vertical dimensions, left and right are both part of the horizontal dimension, 'forward and backward' denote the union of the two directions within a single axis.

In answer then, an isolated point is not a 'simply extended manifoldness', or a 1 dimensional object, because for it no 'progress' is possible. Thinking intrinsically, if you placed your point of view on the point, there are no possible movements you can make in any direction to still remain on the point - you have no degrees of freedom for motion - since your position is completely specified. This total lack of degrees of freedom; corresponding to the complete specification of a location; is why a point is 0 dimensional.

Though Riemann has not ascribed a dimension to points in the paper, only to manifoldnesses which consist of points (in the continuous case). The lowest dimension being a simply extended manifoldness or 1-ply extended magnitude (a line or curve with infinitesimal/0 thickness, strictly speaking I think n-ply magnitudes are associated with n dimensional manifoldnesses, rather than being equivalent to them, but this equivocation here helps more than it hinders. I think later n-ply extended magnitude is a coordinate system notion, which can be used to describe positions on an n dimensional manifoldness). -

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading GroupA point of clarification for me. I'm trying to wrap my head around the idea that you only need one number to specify your location on a 2-dimensional line. — Moliere

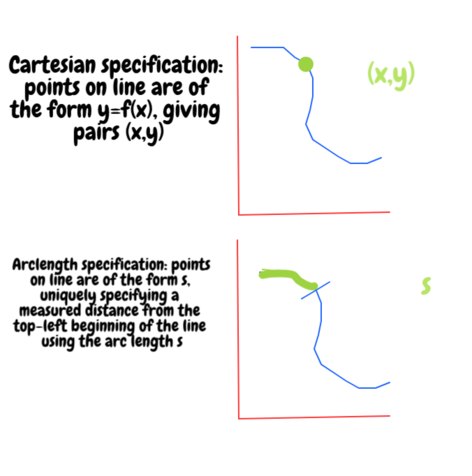

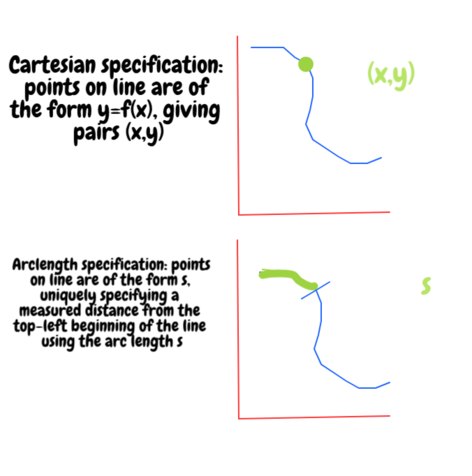

Switching into the language of degrees of freedom can help. A degree of freedom is a unique direction of variation. Straight lines have 1 degree of freedom. If you remember from school straight lines have the equation:

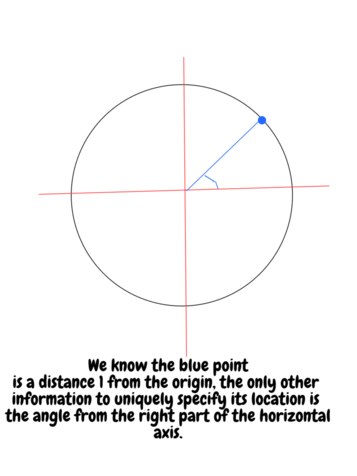

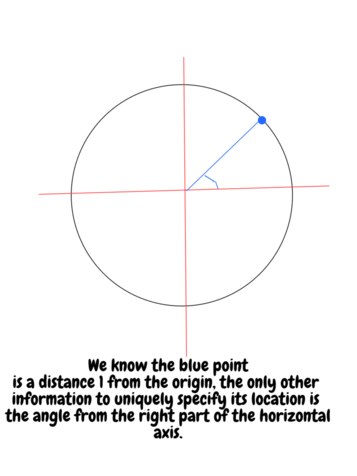

this means if you fix , you determine immediately. The same concept holds for, say, the boundary of a circle. The points laying on the boundary of a circle (with radius 1 centred at the origin) satisfy the equation:

this means that if you fix an , you can determine the (up to sign). Another way of seeing this dependence on a single variable is that you can uniquely specify a point on the boundary of a circle through an angle of rotation:

So when the usual degrees of freedom for expressing a position in space using an angle and a distance from the origin are... the angle and the distance from the origin... and if we constrain the distance to be constant (1, here), we lose a degree of freedom (dimension) from the unconstrained space (of 2 dimensions) by applying one constraint (the distance from the origin = 1).

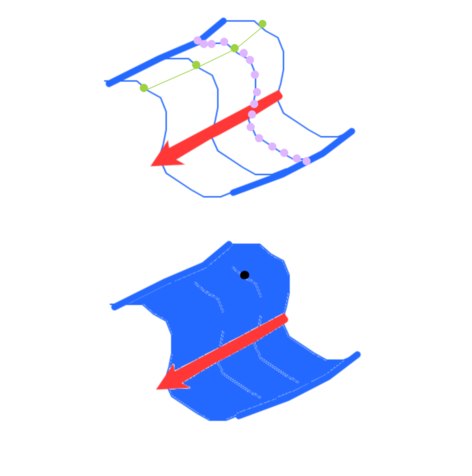

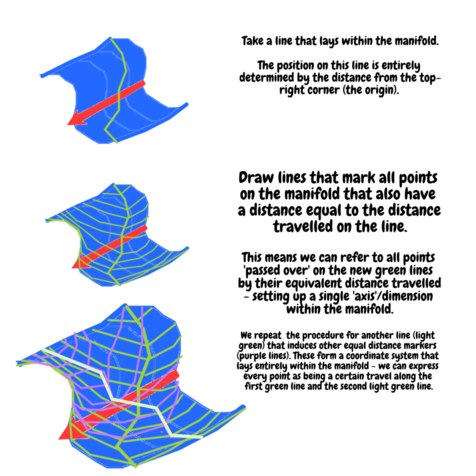

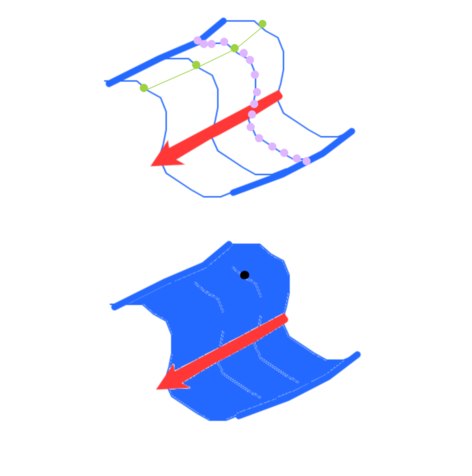

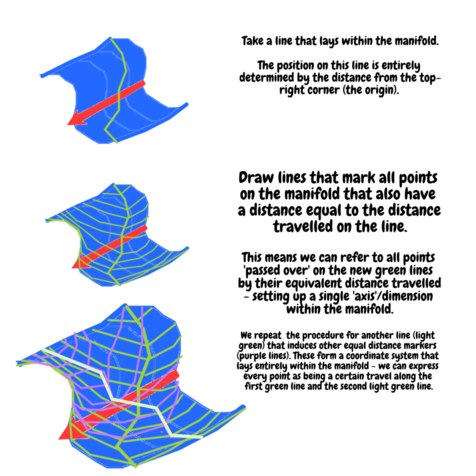

When I showed this with my examples of a 2 D shape with lines on it above, each line creates axes across the shape where the distance would be the same. In the second diagram in that post. I've added the 'lines of constant distance' from the original blue curve we used to sweep over the red one, pictured below.

The green curve denote all the possible positions consistent with being the picked distance travelled on the blue curve, the lilac curve denotes all possible positions consistent with being the picked distance travelled on the red curve. You can see they intersect at one and only one point, the previously specified black one - this is why the black one showed up in the place that it it did. -

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading Group@StreetlightX@John Doe@Moliere@Wallows

Does anyone have anything they want to discuss before we move onto the meatier/more technical bits? -

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading GroupAnother thing which is worthwhile to highlight is that coordinate systems are a way of ascribing positions based on quantities - so we have length magnitudes characteristic of position being translated to numbers which measure the lengths in some system of measurement (coordinate system).

Riemann follows this connection between measurement/metric and coordinate system in the next section. -

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading GroupHere's another demonstration of 'innate coordinates', using the simply extended manifoldnesses (1D manifolds) of the original blue curve and the red arrow to express the position of a point on the doubly extended manifoldness formed from 'sweeping one over the other'.

The black point is what you get when you travel the green point along the blue curve and the lilac point along the red curve. This is equivalent to the usual notion that the coordinate (1,2) in the x-y plane is obtained by going forward along the x/horizontal axis by 1 and forward up the y/vertical axis by 2. Only now we're moving over curves rather than straight lines - transitioning from rectilinear to curvilinear coordinates as @StreetlightX highlighted here. -

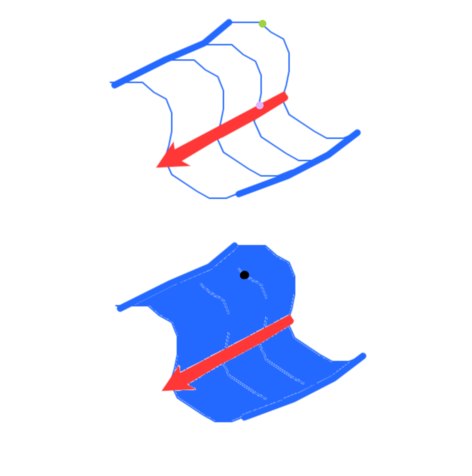

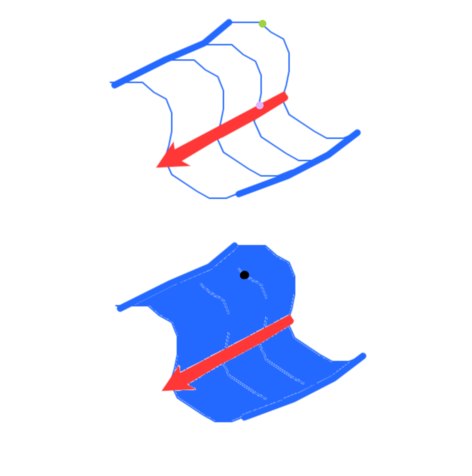

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading GroupRiemann has given us a method for constructing higher dimensional manifolds from lower dimensional manifolds. In §3 he does the reverse, giving us a method to decompose higher dimensional manifolds into lower ones. He switches to the vocabulary of dimensions/variations in the first paragraph of §3, and we can consider each dimension as devoted to a simply extended manifoldness:

I shall show how conversely one may resolve a variability (manifoldness-me) whose region is given into a variability of one dimension and a variability of fewer dimensions. To this end let us suppose a variable piece of a manifoldness of one dimension (simply-extended, me) - reckoned from a fixed origin, that the values of it may be comparable with one another - which has for every point of the given manifoldness a definite value, varying continuously with the point; or, in other words, let us take a continuous function of position within the given manifoldness, which, moreover, is not constant throughout any part of that manifoldness.

'not constant' is a requirement for being a coordinate axis, say if on the usual real line every number between 0 and 1 was normal, it was associated with the correct real number, but every number above 1 was associated with the number 2. This would mean that this direction of variation cannot discriminate between positions which must be represented as quantities greater than 2, 'folding' all of the real line between 2 and infinity into the natural number 2. Riemann describes the procedure as something that looks like this:

(click to zoom) We also could have used distance along the original blue line and the original red arrow as axes, but I wanted to stress that any other pair of independent directions of variation within the manifold would do the same job. This procedure usually works, so long as the dimension of the manifold is finite and that the coordinate system doesn't have singular points. Riemann stresses that infinite dimensional manifolds do exist and are worthy of study:

There are manifoldnesses in which the determination of position requires not a finite number, but either an endless series or a continuous manifoldness of determinations of quantity. Such manifoldnesses are, for example, the possible determinations of a function for a given region, the possible shapes of a solid figure, &c

such as manifolds whose points consist of functions (function spaces) or shapes. This concludes 3 - Riemann's discussion is just describing the above picture and its limitations. -

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading GroupThis is a 1-ply extended magnitude (a bendy 2D line) 'passing over' into a 3-ply extended magnitude (a 4D Volume). This 'skips' the 2-ply extended magnitude because we're rotating the curve, rather than just 'stretching it out' along a single dimension, like was done in fdrake's post. — StreetlightX

If you want to consider the volume of the vase, then the whole circle is a 2 dimensional object we're 'passing over' with the curve which is a cross section of the vase boundary, adding the dimensions gives us that the resultant manifoldness would be of 3 dimensions. If instead we rotate the curve which is a cross section vase boundary solely along the boundary of the circle (the full extent of the radius), we end up with a 2 dimensional vase-surface, since the circle boundary is 1 dimensional and the vase boundary is too (which is what's actually pictured in the wiki link, but it is using this procedure to suggest the volume itself is formed from the rotation by setting up the right vase-boundary). -

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading Group

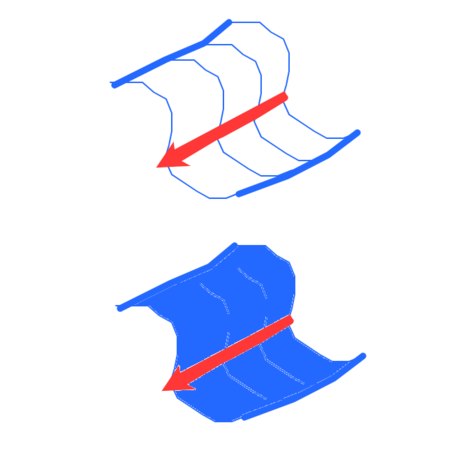

Quick corrective note: Riemann equates simply extended magnitudes with 1 dimensional objects, but the points which constitute them are 0 dimensional. So the point/line/surface/volume are 0/1/2/3 dimensional respectively. In my diagrams, we have a curve passing over another curve, and because it's 2 curves passed over we have 2 dimensions.

He switches to the dimension vocabulary in §3

I shall show how conversely one may resolve a variability whose region is given into a variability of one dimension and a variability of fewer dimensions. To this end let us suppose a variable piece of a manifoldness of one dimension - reckoned from a fixed origin, that the values of it may be comparable with one another - which has for every point of the given manifoldness a definite value, varying continuously with the point...

this procedure, taking a variability of one dimension (a curve) from a manifoldness of higher dimension n, reduces the remaining dimensions of the manifold left unaccounted for by 1. So we end up with n-1 directions for variation when we've already set up the 'variability of one dimension' - a 'simply extended magnitude', since it 'varies continuously with the point'. -

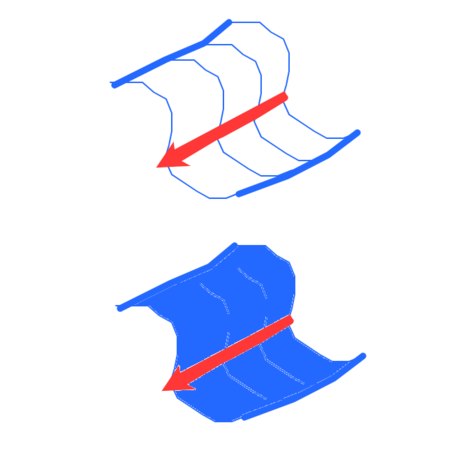

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading GroupSo I think §2 is reasonably straight forward, it's an exercise of the imagination which sets out what Riemann means when he thinks of a multiply extended magnitude.

§ 2. If in the case of a notion whose specialisations form a continuous manifoldness, one passes from a certain specialisation in a definite way to another, the specialisations passed over form a simply extended manifoldness, whose true character is that in it a continuous progress from a point is possible only on two sides, forwards or backwards.

I think the archetypal example here is that of a line segment. I think a specialisation can be harmlessly read as a dimension, or direction of variation. So say we have the following line segment:

(-------)

the specialisations we pass over are the points which constitute it, and together they form the line - the simply extended manifoldness. There are only two directions to travel, forwards and backwards, and this gives the 'true character' of it. This notion is, however, broader than a line, as the boundary of a circle would also be a simply extended manifoldness: we are only travelling 'forwards' through clockwise rotations and 'backwards' through anticlockwise rotations, assuming we lay on the circle's boundary.

Inherent in this is the idea of parametrising a movement with respect to the changes in a single direction of variation, and one common way of doing this is by parametrising the position on a shape by the distance required to travel to it while remaining within the shape, the arclength.

Thinking about it in terms of travel on the manifold (the line above) reveals how many directions of variation are required to express its variations innately - we only need one, the arc length, because it's one dimensional. This is a simply extended manifoldness, one of a single dimension.

If one now supposes that this manifoldness in its turn passes over into another entirely different, and again in a definite way, namely so that each point passes over into a definite point of the other, then all the specialisations so obtained form a doubly extended manifoldness.

Now we make the above blue line 'pass over' another red line, creating a doubly extended manifoldness:

which, note, can have the points on it described by the arclength along the first blue line and the arclength along the second red one (the arrow). This means it is 2 dimensional (despite it being embedded in 3-space).

In a similar manner one obtains a triply extended manifoldness, if one imagines a doubly extended one passing over in a definite way to another entirely different; and it is easy to see how this construction may be continued. If one regards the variable object instead of the determinable notion of it, this construction may be described as a composition of a variability of n + 1 dimensions out of a variability of n dimensions and a variability of one dimension.

And Riemann iterates the procedure, giving a recipe for constructing a manifold of n+1 dimensions from a manifold with n dimensions and a manifold of 1 dimension. This procedure is usually called 'sweeping out' space, and usually first appears in undergraduate or school calculus when discussing volumes of revolution, the Wiki link there has another good picture of 'sweeping out' a 2 dimensional surface using a 1 dimensional surface (and a circle/axis of rotation).

Another thing to highlight here is that Riemann is looking at composing higher dimensional shapes out of lower dimensional shapes; the dependence on the coordinate system used to express either is like map to the territory, the shapes are the shapes, the manifolds are the manifolds, regardless of the particular coordinate system used in their description. -

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading Group@John Doe,@Moliere,@StreetlightX - already a lot to discuss. Hurrah. Let's hope it continues going this well.

-

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading GroupFinishing my exegesis of §1

Definite portions of a manifoldness, distinguished by a mark or by a boundary, are called Quanta.

definite portions could be elements, like A in {A,B} portions of discrete manifoldness, distinguished by a mark (A). Or they could be points, like the circle with radius 1 centred at 0 in the plain. I want to emphasise along with Street (and highlight since it's super important), that treating the circle as a space unto itself, as a thing with its own properties independent of the coordinate system used to describe it, is a really novel way of thinking that Riemann helped create.

Their comparison with regard to quantity is accomplished in the case of discrete magnitudes by counting, in the case of continuous magnitudes by measuring.

I'll take it that counting is straightforward. But note here that Riemann is operationalising the concept of size with the concept of quantity; that is, we may express sizes using numbers. In the discrete case this is just counting, in the continuous case this is measuring.

Measure consists in the superposition of the magnitudes to be compared; it therefore requires a means of using one magnitude as the standard for another. In the absence of this, two magnitudes can only be compared when one is a part of the other; in which case also we can only determine the more or less and not the how much.

I think I read this bit a little differently from @StreetlightX, but our two accounts are complementary rather than opposed. I'm imagining something like the norm of a vector in a vector space. So a norm in a vector space (roughly) is a function that takes the vector to number which represents its length. The usual norm we have in Euclidean spaces is Pythagoras' theorem. If we have the point (3,4), 3 along 4 up in the plane, the distance it is from the origin is the hypotenuse of the triangle:

What this sets up is an embedding of position notions in the plane to position notions on the number line. IE, we have 'superposed' positions (magnitudes) in the plane (x=3,y=4) by taking them both as arguments of a function (f(x,y)=sqrt(x^2+y^2) with x=3, y=4) and used this function to map the position in the plane to a position on the line (sqrt(3^2+4^2)=sqrt(9+16)=sqrt(25)=5), which is then treated as a quantity that expresses the size (magnitude) of the position in the plane. In the absence of such an idea, a metric - a means of measurement -, we can only compare relative sizes through subset relations, such as (-----) being shorter than (-----------), which moreover is achieved without the explicit ascription of quantity.

However, note that this metric requires some kind of coordinate system - a means of expressing positions in terms of quantities -, and Riemann emphasises that we should instead consider the notion of coordinate system as conditioned by/associated with the objects (manifoldnesses/manifolds) whose points are commensurable under them. As he puts it:

The researches which can in this case be instituted about them form a general division of the science of magnitude in which magnitudes are regarded not as existing independently of position and not as expressible in terms of a unit, but as regions in a manifoldness.

What this does to the above idea of 'metric' is that it requires that such metrics, systems of measure on manifolds, become localised and indexed to the local topography of the manifold itself. This is a historical antecedent to condition (1) here, emphasising that systems of measure (coordinate systems and 'superpositions' like metrics) need only obtain locally on a manifold.

Such researches have become a necessity for many parts of mathematics, e.g., for the treatment of many-valued analytical functions; and the want of them is no doubt a chief cause why the celebrated theorem of Abel and the achievements of Lagrange, Pfaff, Jacobi for the general theory of differential equations, have so long remained unfruitful.

In terms of Riemann's argument, this is one of those bits of fluff that you'd send in a research grant application. It's just saying that the inquiry Riemann will do has practical consequences for maths. Riemann then provides an orienting, preparatory remark for §2 in which he'll describe multiply extended magnitudes consistent with the concerns in §1.

Out of this general part of the science of extended magnitude in which nothing is assumed but what is contained in the notion of it, it will suffice for the present purpose to bring into prominence two points; the first of which relates to the construction of the notion of a multiply extended manifoldness, the second relates to the reduction of determinations of place in a given manifoldness to determinations of quantity, and will make clear the true character of an n-fold extent.

Which states the research objective of treating manifolds as spaces unto themselves, but nevertheless finding systems of measurement that express their local topography. Moreover, he'll deal with the 'general case' of 'multiple extension', when we have as many directions of extension (dimensions/independent directions of variation) as we require. For example, 2 for the surface of a sphere despite it being in 3-space. -

Is cell replacement proof that our cognitive framework is fundamentally metaphorical?↪fdrake And my axe. I've had it for forty years. After breaking many a wooden handle, I replaced it with fibreglass. I found I was buying cut logs, so I replaced the felling head with a splitting maul. It's a blood good axe. — Banno

I don't put much stock in the Ship of Theseus. At most it shows that concepts can have fuzzy boundaries. All I wanted to do in the thread was to highlight that it's rebranded old hat, like the Matrix being a new way of phrasing the Cartesian daemon in skeptical arguments. -

All A is B and all A is C, therefore some B is C

No idea what you're talking about. See here. Usually however we are not talking about empty domains or inexistent objects. -

All A is B and all A is C, therefore some B is C

So long as you're not dealing with an empty domain, and you know this a priori. The universal quantifier is equivalent to 'not for some x not (rest of expression)', and trivially when there are no x's, the statement to the right of the first not '(for some x not) is false because there are no x, thus the whole statement is true, since it is the negation of a falsehood. -

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading Group

So the specialisations bit, this is now discussing §1 in the paper:

Magnitude-notions are only possible where there is an antecedent general notion which admits of different specialisations. According as there exists among these specialisations a continuous path from one to another or not, they form a continuous or discrete manifoldness; the individual specialisations are called in the first case points, in the second case elements, of the manifoldness.

We can only have magnitudes expressed mathematically if there exists a general concept of size (relating to previous philosophical concerns) which we can tailor to specific contexts. Like we can imagine lengths as represented by numbers with a length dimension, times as numbers with a time dimension, collections of distinct objects with numbers (cardinalities) that give how many distinct objects there are.

The distinction between continuous and discrete manifoldnesses seems to depend on whether we can 'travel' from one element of the manifold to another 'through other elements laying within the manifoldness' - so we can link two points on a bit of paper with a line, making the sheet of paper continuous manifoldness, but we couldn't link the letters A and B with a letter 'between' them, or the numbers 1 and 2 with a natural number 'between' them.

Another way of constructing a discrete manifoldness, say, would be to imagine two non-overlapping spheres in space. There are points between them, but no points between them which are also points on the sphere - and thus no points between them which are part of the coordinate systems giving the points on either sphere, so paths between them are blocked, making a discrete manifoldness.

The 'ability to travel through/on the manifold from one point to another' is related to points (1) and (2) in my previous post discussing the modern notions of manifold ('manifoldness') that developed after Riemann. It is related to point (1), because this allows us to express 'local changes of position' using the coordinate system. This equates to the condition of being locally connected. But the notion Riemann discusses is more broad, I think, because guaranteeing that all the 'specialisations' (points in the continuous case) have a continuous path from one to the other on/through the manifold would make it a connected space. Though I think that the usual Riemannian manifolds - the one the paper inspires - are indeed fully connected in the 'continuous path from every point to every other' sense. Note that coordinate systems are used to express these paths, but the paths themselves are part of the manifold and not tied to the specific coordinate system used to express the path.

(Edit: as an aside, look at this pathological motherfucker, connected but not path connected or locally connected!)

Riemann goes on to say that:

Notions whose specialisations form a discrete manifoldness are so common that at least in the cultivated languages any things being given it is always possible to find a notion in which they are included.

I imagine this commonality as coming from him having countable or finite collections of object in mind. So we can count chairs or coffee cups or insects or items of food. So the aside he makes:

(Hence mathematicians might unhesitatingly found the theory of discrete magnitudes upon the postulate that certain given things are to be regarded as equivalent.)

suggests something like the following procedure. We might define the number, 2, say as the equivalence class of sets with 2 elements, so {A,B} and {C,D} could both be regarded as exemplars of the number 2, since both have 2 elements. They're equivalent because we require the same number of discrete labels (A,B for the first, C,D for the second) to attach to all the elements. This line of thought was actually developed, and numbers can be characterised as collections of sets with their elements relabelled (IE that one-to-one correspondence holds between the two, and all other sets with 2 objects in 'em). I also think he has distinct objects in mind that we usually encounter because he contrasts the massive number of cases where we can count stuff or label stuff exhaustively vs cases where we cannot; examples of continuous manifoldness.

On the other hand, so few and far between are the occasions for forming notions whose specialisations make up a continuous manifoldness, that the only simple notions whose specialisations form a multiply extended manifoldness are the positions of perceived objects and colours. More frequent occasions for the creation and development of these notions occur first in the higher mathematic.

IE, the canonical examples of continuous manifoldness being colour spectra and position in space. But the expressive power of math is much greater than this; suppose there is a continuous path between every pair of elements, then we have a continuous manifoldness by definition. We could do this with space-time, we could express the motion of a car with respect to the driver's wheel turning angles and its forward motion, we could aggregate colours together with sound frequencies or perceived colours together with frequency measurements, and these things would be examples of continuous manifoldness (since they strongly resemble 2-D Euclidean space) since mathematics allows us the freedom to consider both together, at once, as a unitary abstraction and study/ascribe relationships to the components. Note that these space-like concepts do not correspond to our usual phenomenological spatial directions, so the notion of 'multiply extended magnitude' is broader. We could even consider, say, mass as a continuous manifoldness (since it's a real number greater than or equal to 0!), and give it a local geometry (flat in this case).

The notion of splitting manifolds up into components, informally independent directions of variation, is the subject of §2, the next paragraph (but I haven't finished writing about §1 yet). -

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading GroupI was reading another paper about Reimann online, and from it I gleaned that I was sort of misreading "manifoldness" -- whereas I was sort of analogizing it with a vector before -- which I really only understand to be a magnitude with a direction -- it seemed to make more sense that Reimann is actually talking about the coordinate system itself. So Euclid or Cartesian coordinates are one example of a manifold, but the manifold could differ from these. — Moliere

I think this is right. A manifold is essentially an object with a coordinate system associated with it. So like a sphere, or the boundary of a circle, or even the entirety of our infinite space in any number of dimensions.

A key insight in the mathematics of manifolds is that 'the' coordinate systems is kind of extraneous to it, in the same sense that a circle is still the same circle no matter whether you express all its points through the usual (x,y) coordinates, or in terms of a distance from its centre r and an angle of rotation t - the shape doesn't change, the circle is the circle, we've just altered its manner of representation.

This provokes defining manifolds with respect to all the coordinate systems they are compatible with, so definitions of manifolds quantify over coordinate systems and ensure that these coordinate systems 'chart' neighbourhoods around every point on the manifold, and moreover the coordinate systems associated with a manifold have to be able to be transformed seamlessly into each other. If this seems abstract, imagine that we rotate the y axis in the x-y plane 45 degrees to the right, the underlying space is the same, and we have a formula to translate positions assigned in the original x-y plane coordinates to the rotated version (a similar construction exists for the circle example, r^2 = x^2 + y^2, the angle t being measured from the right part of the x-axis through trigonometry, tan(t)=y/x).

The highlights in the modern definitions are:

A (smooth) manifold is a set of points considered together with a set of coordinate systems. These points and the coordinate systems must behave in the following way:

(1) that every neighbourhood of a point in a manifold (think of a closed loop drawn around the point = neighbourhood) has to be able to be expressed in some coordinate system associated with it.

(2) that every coordinate system associates neighbourhoods of points to the usual mathematical Euclidean space in a one-to-one fashion.

(3) The coordinate systems associated with a manifold must be able to be smoothy transformed into each other (like a coffee cup into a donut in the usual example).

(1) mirrors the idea of 'localised geometry' or relating to the focus Riemann has on infinitesimal calculations in the paper; the infinitesimal parts might be Euclidean or not, the space might be locally Euclidean but over large (or infinite) regions of space not; hence concerns of 'going beyond the limits of observation' - manifolds both have an infinitesimal aspect (localised geometries) and an infinite one ('really big' regions might not respect the infinitesimal relationships/local geometries derived or ascribed). [Condition (2) ensures, however, that we have an object which is locally Euclidean, but Riemann introduces this conception later.]

(2) mirrors the concerns Riemann has about quartics and quadratics in the distance notions ('square root of a quadric (quadratic, x^2 terms)' vs 'fourth root of a quartic (x^4 terms)', the notions that have 'square root of a quadric' are locally Euclidean in the way our universe and perceptions (allegedly) are.

(3) mirrors the concerns of intrinsic vs extrinsic thinking, nothing about a shape should depend on how we describe the positions of points on it, this would be like saying the map manipulates the territory, or the surface of the Earth is given its shaped by our lines of longitude and latitude. -

Is cell replacement proof that our cognitive framework is fundamentally metaphorical?Do you see any distinction between the issue in the OP and the Ship of Theseus?

-

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading Group

I forgot to say, I'll move onto the next section once you've had chance to comment. I might be attuned to the math but I don't think I am to the broader philosophical relevance, despite my efforts to immediately link it to Kant. -

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading Group

I'm happy to put up maths notes explaining what I can. I'm also having to learn more differential geometry to write the exegesis, since I've never studied it outside a tiny undergrad reading group. -

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading Group

I imagine that even without understanding the math, as I won't at points without lots of work (I have a first principles/pedagogical differential geometry textbook I'm referring to to orient myself, I can definitely not send it to people if they want it), I still think it's possible to get something out of the flow of the argument. Bracketing the specifics of the mathematical reasoning and treating it like a phenomenology of space; or a highlighter of differences and commonalities between the phenomenology of space and possible ways of conceiving it mathematically. -

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading GroupI think that the "darkness" referred to above is the relations between the assumptions geometry has -- I take it he means the 5 postulates of Euclids system as the primary example, though he does allude to the thought that there can be other axioms. As I read him here it seems that Reimann is motivated to understand the possible justification for just these axioms, and wants to understand the relationship they have to one another -- whether they are necessary, whether they are universal, and whether they are even possible. — Moliere

Third post in a row, sorry fellow mods, I got too excited and hit the 'Post Comment' button too quickly.

I think this is about right, wondering how Euclid's system 'fell out of' our experiences and intuitions is probably something driving Riemann's engagement here; and the ability to define what makes a concept of space like the one dealt with in Euclid invites/renders possible mathematical suppositions contrary to it.

I suppose this relates to broader themes in philosophy. Mathematics is usually considered a largely a priori exercise - yet here we are with a certain plurality and non-determination within it, as if there are competing images/accounts to be had. All of which equally good and true in supposition - treating them purely mathematically -, but now the plurality invites questions of which suppositions are right. To borrow Kantian vocabulary, we either sever the pure intuition of space from the objects it phenomenally conditions or admit a multiplicity of pure intuitions of space which may apply in different mathematical or experiential contexts.

Edit: another possibility is that, say, 'the' pure intuition of space isn't necessarily captured by Euclid's work and presuppositions, driving a wedge between the intuitions embodied in Euclid's assumptions and the necessity of their connection with objects. 'The' pure intuition may admit of multiple space concepts consistent with it. -

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading Groupit. The reason of this is doubtless that the general notion of multiply extended magnitudes (in which space-magnitudes are included) remained entirely unworked — Moliere

The modern notions of coordinate systems and vectors weren't well established at the time of Riemann's writing. Moreover, as will become more clear (I think) in the first section, he sees these 'coordinate system' like concepts as just an expression of something more basic about the objects considered. This desire to treat objects, surfaces and so on 'intrinsically', rather than through the 'extrinsic' ideas/representational powers of coordinate geometry is a style of thinking Riemann helped found in this paper - where we can see many germinal forms of now precisely articulated mathematical concepts. -

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading GroupAnother note I have is that notions like coordinate system, manifold, set and so on are not precisely established in mathematical discourse at the minute. The paper is 'conceptually positioned', so to speak, in wrestling with appropriate definitions of the mathematical concepts it treats. In a certain sense, looking at the history of mathematics as a field of study lets us peer under the bonnet of mathematical formulae and theorems to the imaginative background they fall out of.

This also means, then, that whenever I'll use a more contemporary mathematical example or analogy, it will make an omission through excessive clarity - like reading the idea of a vacuum back into the aether, or treating phlogiston as a rung on the scientific ladder used to climb toward energy. -

Just curious as to why my post was deletedIt's difficult to meet the different requirements that really have nothing to do with the content being offered. I gave a link to the first three chapters of a very important work. Why in the world would a moderator take it upon himself to delete it without an explanation and a way to rectify it. Fdrake, you say that I have to offer an OP. I don't have a blog and this book is not based on opinion, so I can't write an opinion piece. I can try to explain in my own words (with help from excerpts in the book) the author's reasoning as to why man's will is not free, and what important knowledge lies locked behind this hermetically sealed door. — Janis

If you're that passionate about the subject, try again, tackle a specific issue the book deals with in some amount of depth. Don't just quote from it or reference it, explain it in detail and why it's relevant. -

Just curious as to why my post was deleted

Though I wasn't the mod that removed it, I'd allow a link to a blog post or a personal book if the OP was very well written, sufficiently in depth, and likely to generate good discussion. You can't just... Oh, Street said the same thing. -

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading Group

-

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading GroupStill in "Plan of the Investigation", now the second paragraph.

From Euclid to Legendre (to name the most famous of modern reforming geometers) this darkness was cleared up neither by mathematicians nor by such philosophers as concerned themselves with it. The reason of this is doubtless that the general notion of multiply extended magnitudes (in which space-magnitudes are included) remained entirely unworked. I have in the first place, therefore, set myself the task of constructing the notion of a multiply extended magnitude out of general notions of magnitude. It will follow from this that a multiply extended magnitude is capable of different measure-relations, and consequently that space is only a particular case of a triply extended magnitude. But hence flows as a necessary consequence that the propositions of geometry cannot be derived from general notions of magnitude, but that the properties which distinguish space from other conceivable triply extended magnitudes are only to be deduced from experience. Thus arises the problem, to discover the simplest matters of fact from which the measure-relations of space may be determined; a problem which from the nature of the case is not completely determinate, since there may be several systems of matters of fact which suffice to determine the measure-relations of space - the most important system for our present purpose being that which Euclid has laid down as a foundation. These matters of fact are - like all matters of fact - not necessary, but only of empirical certainty; they are hypotheses. We may therefore investigate their probability, which within the limits of observation is of course very great, and inquire about the justice of their extension beyond the limits of observation, on the side both of the infinitely great and of the infinitely small.

Hoo boy.

From Euclid to Legendre (to name the most famous of modern reforming geometers) this darkness was cleared up neither by mathematicians nor by such philosophers as concerned themselves with it.

So Riemann's saying that the mathematical accounts in history, while possibly providing different conceptions of space (as comparing Euclid to Legendre and later Gauss), did little to remove the void of darkness between mathematical intuitions of space and their axiomatisations; to name the darkness, I think it is characterised by the questions: "What do our intuitions (1) say about the axioms (2)? And what do the (2) axioms say about our intuitions (1)?", characterising the relationship between (1) and (2) from both sides as it were.

The reason of this is doubtless that the general notion of multiply extended magnitudes (in which space-magnitudes are included) remained entirely unworked.

Space magnitudes seem to be treated as 0 dimensional points, 1 dimensional lines, 2 dimensional areas and 3 dimensional volumes. Space-time in the Einsteinian sense would also be a 'multiply expanded magnitude' and space concept.

So what's the commonality here? I believe when Riemann is considering a 'multiply extended magnitude', he's thinking of a vector of the appropriate dimension, a 'position' in a space. So a 1 dimensional line becomes <x>, ranging from -1 to 1 draws the usual section of the number line between [-1,1], a 2 dimensional area becomes characterised in the form <x,y>, with constraints on <x,y> to specify the area (eg x^2+y^2<=1 for a circle centred at the origin with radius 1) or <x,y,z> to specify a volume (with x^2+y^2+z^2<=1 for a sphere centred at the origin with radius 1). (Edit: though it's worthwhile noting here that 'coordinate system' is maybe a better representation of the concept, but the distinction between vector space and coordinate system probably doesn't matter at this point in the exegesis, in which the concepts are fuzzy) The idea of a 'multiply extended' magnitude is just that of a collection of 1 dimensional magnitudes.

Note at this point we have a sense for the 'size' of 1 dimensional, 2 dimensional and 3 dimensional magnitudes - length, area, volume-, and we also have multiply extended magnitudes being a collection of independently varying 1 dimensional magnitudes (the x and y directions in the plane, say, are both 1 dimensional magnitudes which together form a 2 dimensional magnitude). So Riemann sets himself the task of:

I have in the first place, therefore, set myself the task of constructing the notion of a multiply extended magnitude out of general notions of magnitude.

defining/mathematically characterising/axiomatising notions of size (like length, area, volume) for multiply extended magnitudes (like lines, circles, spheres). But it is worthwhile to note that Riemann is explicitly considering notions of space, so we're considering things 'one layer back' from lines, circles, spheres - we're considering ways of linking geometries to sizes. The first example of which in the paper is trying to construct/axiomatise the usual notion of length/area/volume in Euclidean space. So when Riemann says:

It will follow from this that a multiply extended magnitude is capable of different measure-relations, and consequently that space is only a particular case of a triply extended magnitude.

he's talking about the fact that completely characterising, say, the relationship between space and volumes mathematically - you can change this relationship in accord with some notion end up with an inequivalent notion of space. This drives a 'hard wedge' as it were between the necessity of the relationship between (1) the space intuition and (2) its complete axiomatisation; there is now more than one space intuition/notion, revealed by the ability to modify axioms/characterisations of space. Shifting vocabularies, there's no unique mathematical 'space intuition' a priori, since we can characterise others - and perhaps, tentatively, this means the reason for the darkness between (1) and (2) is an elision inherent in previous geometric thought generated by the belief that studying space intuitions always meant articulating a single a priori notion of space (eg Euclidean space, that which is described by Euclid in his Elements). Because of this

hence as a necessary consequence that the propositions of geometry cannot be derived from general notions of magnitude

(because of the plurality of magnitude notions revealed by Riemann's approach) and thus:

the properties which distinguish space from other conceivable triply extended magnitudes are only to be deduced from experience.

we must recognise what space-like notion is appropriate for whatever purposes we may have. Riemann then seeks to find indicators - necessary and sufficient conditions / characterisations - of notions of space (and multiply extended magnitudes more generally) - of which space concept is appropriate for which purpose.

Thus arises the problem, to discover the simplest matters of fact from which the measure-relations of space may be determined; a problem which from the nature of the case is not completely determinate, since there may be several systems of matters of fact which suffice to determine the measure-relations of space - the most important system for our present purpose being that which Euclid has laid down as a foundation.

and moreover the existence of multiple n-dimensional magnitude concepts (like the link between 2 dimensional spaces and areas) severs the a priori connection between Euclidean space(s) and space, as n dimensional magnitude, simpliciter.

One illustrative example here is that for distances on the surface of the Earth, if they're short we can use Euclidean geometry to calculate them, but if they're long we can't - the surface of a sphere is not Euclidean, it wraps around itself, it has curvature and so on.

Thus, the a priori necessity of space being Euclidean space, or more generally of space being uniquely characterised, is broken by the plurality of n dimensional magnitudes and measures of their length/area/volume. In essence, Riemann is playing a game of constructing counterexamples to Euclidean space after characterising precisely what it is! Find the boundaries of the concept, find the exceptions, and vice versa.

Because we no longer have the a priori necessity of our calculations about space, destroyed by the non-uniqueness of space concepts, this renders which space concepts nature can be modelled by as a matter of investigation:

These matters of fact are - like all matters of fact - not necessary, but only of empirical certainty; they are hypotheses. We may therefore investigate their probability, which within the limits of observation is of course very great, and inquire about the justice of their extension beyond the limits of observation, on the side both of the infinitely great and of the infinitely small.

and of purely mathematical consequences/assumptions of them ('beyond the limits of observation').

The relationship to infinitely great and infinitely small probably connotes the fact that Riemann will be studying space at multiple scales; the geometry relationship between 2 dimensions and volumes, say, becomes defined with respect to infinitely small variations (like dx and dy in calculus), and it may be that on larger scales different mathematical patterns can hold even within the same notion of space (like my sphere example above).

Edit: note that when I'm using <> to surround something, that's notation that refers to a coordinate system being in play. So EG <x> denotes a position on (something like/for example) the real line, <x,y> denotes a position in in the plane (or something like it/for example) and so on. -

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading GroupGuess I'll start today rather than tomorrow since tomorrow is busy. Here is a copy of the paper that's in plain text (so it allows quotation through copy/paste).

Section 1: Plan of the Investigation.

It is known that geometry assumes, as things given, both the notion of space and the first principles of constructions in space. She gives definitions of them which are merely nominal, while the true determinations appear in the form of axioms.

I think the first sentence is an attempt to characterise the study of geometry. In my mind here I'm imagining he's talking about Euclid's elements as an example. The logical structure Riemann seems to be given to geometry is as a composite of:

(1) intuitions about space "the notion of space"

(2) (mathematical) rules which characterise the intuitions.

and these things are treated as a unit; that we have characterised all our intuitions about space, the space construction/model within mathematics (Euclidean space), through a successful determination of mathematical rules which characterise them.

So when Riemann writes " She gives definitions of them which are merely nominal, while the true determinations appear in the form of axioms.", he's saying that the supposed unity between (1) and (2) is actually just a predisposition of interpretation, and we can do with (2) alone to characterise a notion of space. Thus the fact that:

The relation of these assumptions remains consequently in darkness; we neither perceive whether and how far their connection is necessary, nor a priori, whether it is possible.

is ensured by the duality of mathematical rules characterising the mathematical nature of space, but we suppose that these rules, the axioms, give a complete characterisation of the intuitions we may have, (1). What Riemann is doing here is driving a wedge between intuitions of space as studied in (Euclidean) geometry and the necessity of application of those intuitions to all possible mathematical space concepts.

I imagine anyone with a familiarity of the Transcendental Aesthetic in Kant will already find this argument extremely interesting. So I think Street is very right in their emphasis that:

The basic idea is this: Riemann is saying that space as we know it - the kind of space in which me move around and live - is but a particular case of a more general notion of space which can be constructed from 'general notions of magnitude'. Or, put the other way, one can construct more kinds of spaces out of 'general notions of magnitude' than only the kind of the space in which we live in. — StreetlightX

and I would add that this follows from our ability to play with axioms to posit new spaces to have intuitions about. Or inversely to refine and add specificity to our intuitions of (maybe Euclidean) space by codifying them in appropriate axioms. -

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading Group

One of the reasons why it's so dense is because he's inventing lots of, what are now distinct, mathematical concepts at once. But he's not using the usual words for them (most of the time). EG, n-ply extended magnitudes seem to be n dimensional vector spaces, discrete manifoldness and its elements are like countable sets, continuous manifoldness and its elements are like the real numbers between [0,1], quanta are either elements of countable sets or bounded, connected regions of (possibly higher dimensional) space. Things like (paraphrasing) "mathematicians might unhesitatingly found the theory of discrete magnitudes upon the notion that certain things are to be found equivalent' seem to be ur forms of things like natural numbers being defined as bijection isomorphism classes of finite sets (eg, {a,b,c} and {d,e,f} are just relabelled forms of each other and both could represent the number 3). And this is all just stuff on the first page.

So yes, it's hard going, even for someone with lots of training in math. -

Kuhn, Feyerabend and Popper; Super ShowdownImmediately after what I quoted previously, Peirce added that "this acceptance ranges in different cases--and reasonably so--from a mere expression of it in the interrogative mood, as a question meriting attention and reply, up through all appraisals of Plausibility, to uncontrollable inclination to believe." — aletheist

Yeah fair enough then. -

Kuhn, Feyerabend and Popper; Super ShowdownAt length a conjecture arises that furnishes a possible Explanation, by which I mean a syllogism exhibiting the surprising fact as necessarily consequent upon the circumstances of its occurrence together with the truth of the credible conjecture, as premisses. On account of this Explanation, the inquirer is led to regard his conjecture, or hypothesis, with favor. As I phrase it, he provisionally holds it to be "Plausible." — aletheist

I imagine this 'necessarily consequent upon the circumstances of its occurence together with the truth of the credible conjecture, as premises" might work quite well for engineering or physics, but it doesn't precisely characterise the generation of credible conjecture in statistical applications. Rather, 'plausibility' looks more like high conditional probability, so instead of following with necessity it follows from high (subjective) probability as determined by competence and intuition of the researchers involved and of the complexity of the issues involved in the interpretation of C. -

Is it possible to imagine 4th dimensionI've put 5 in a plot before at work. 3 spatial dimensions illustrating a trend, an animation conveying the transformation of that trend over time, and a colouring over the shape to indicate how a discrete variable changed over time and space.

-

What is a reflexive relation?

The rules are just the set of pairs. They model different types of modality. EG if you wanted to model sequential counterfactuals and non-time symmetry, you might want a sequence of worlds where you can't access previous ones (making the relation anti-symmetric or an order like <). The sense of possibility you want to capture is modelled by the set of pairs you throw into the accessibility relation.

fdrake

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum